1. Introduction

Increasing the energy productivity of the global economy is considered as a key step to combat climate change and ensure the sustainable use of energy and natural resources in the planet. Apart from structural factors that can affect energy productivity, a major part of such an improvement is to raise the energy efficiency of an economy. The International Energy Agency calls energy efficiency as ‘the first fuel’, meaning that fuel use avoided due to efficiency measures is greater than the actual use of any other fuel, and outlines the several benefits brought about by energy efficiency improvements—such as reduction in emissions of both greenhouse gases and air pollutants, improvement of energy security and adaptation to climate change [

1]. However, it is not straightforward to realise the full energy efficiency potential that exists in all economic sectors. Policies fall short of achieving the energy savings foreseen because they often ignore aspects such as heterogeneity in consumer behaviour, local market conditions, technical constraints and financial barriers; this leads to an ‘energy efficiency gap’ whereby theoretically optimal energy efficiency policies have a clearly inferior outcome when implemented in real life [

2,

3].

This paper presents results from the first in-depth study on the energy efficiency potential in the Republic of Cyprus, with a focus on the residential and commercial building sectors, which are responsible for about 40% of energy use and 60% of electricity use in Europe [

4,

5] and about one third of total energy demand in Cyprus [

6]. As the large majority of buildings is concentrated in urban areas, where half of the global population lives, making the most out of this potential is crucial for ensuring climate resilience and resource efficiency for cities and their inhabitants.

Cyprus is an island nation located in the Eastern Mediterranean with a population of close to one million inhabitants, which is a member of the European Union (EU) since 2004. Having enjoyed sustained economic growth since the 1980s, the country was in need of an economic adjustment programme after 2010 in order to attain a sustainable banking sector and public finances. The economy of Cyprus experienced two years of recession (2013–2014) but then the economic rebound was faster than expected, and as of this writing (end of 2017) the medium- and long-term economic outlook is quite optimistic.

Energy use in Cyprus has broadly grown in line with national economic output. After the economic crisis, a stagnation or even reduction in final energy use was observed, although fuel shares in final energy demand have not been affected. Following international trends, electrification is rising throughout the economy. The country’s dependence on petroleum products is still very high, despite discoveries of natural gas off the southern coast of the island, which has yet to be exploited. This dependence has obvious adverse effects on the island’s energy security but also on energy costs: electricity retail prices are highly dependent on international oil price fluctuations and are among the highest in Europe [

7]. National energy intensity also ranks highly for European standards, for a number of reasons—lack of adequate public transport, absence of energy performance requirements for buildings until the mid-2000s, and the exclusive dependence on aviation for international travel. The need to improve energy efficiency is thus obvious.

The expected impact of climate change underlines the importance of an energy transition for Cyprus: the island already has a semi-arid climate and is located in the region, which is projected to experience the most serious climate change effects in Europe, with significant temperature increases, especially in summer, and drops in already low rainfall levels [

8]. As a result, both energy supply and demand are expected to be considerably affected [

9]; this reinforces the need for energy refurbishments of buildings so as to increase climate resilience—in this case energy efficiency contributes to climate change adaptation.

As an EU member, Cyprus has implemented policies promoting renewable energy and energy efficiency measures in compliance with the relevant EU legislation. Although the country is expected to fulfil its 2020 targets, the 2030 EU energy and climate objectives are much more challenging. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the economic sectors not subject to the EU Emissions Trading System will require substantial effort in implementing new policies and mobilizing financial resources. Improving the energy efficiency of non-ETS sectors (mainly buildings, transport and industry) is a high priority for decarbonising the Cypriot economy. Especially for buildings, the national government has proceeded with several funding schemes in the last decade, focusing mainly on residential buildings and trying to make energy renovations attractive to less informed or risk-averse energy users, aiming at consumer certainty and financial grants that ensure a short payback period of investments. Moreover, a number of public buildings have undergone refurbishments with the aid of public funds, in order to ensure compliance with EU legislation.

This paper presents the most comprehensive energy efficiency assessment in Cyprus, with a focus on residential and commercial buildings. Different energy models were combined in order to conduct simulations and provide recommendations to national energy and economic authorities so that the country can meet its energy and decarbonisation targets. The study assessed both the maximum theoretically available potential for energy efficiency improvements and the economically viable potential, and then translated these assessments to aggregate energy demand forecasts. The most important part of the study, which is the focus of this paper, was to provide policymakers with a ranking of energy efficiency interventions in buildings as regards their cost-effectiveness with a series of indicators. Although most of these indicators have been used in previous studies and are considered to provide important information to regulatory and financial decision makers [

10,

11,

12,

13], to our knowledge this is the first paper that combines such a rich variety of indicators in order to come up with realistic policy recommendations.

To arrive at these policy conclusions, we first employed a robust engineering methodology to assess the maximum technical potential for energy savings in the buildings sector. Then we collected economic data for energy efficiency interventions from the national market; took into account realistic financial and technical constraints for Cyprus; constructed diverse cost-effectiveness indices on the basis of engineering modelling results and economic data; and provided finally a ranking of different interventions that can be exploited by authorities to determine their funding priorities. The paper follows this structure, and ends with some recommendations about overcoming financial barriers and enabling energy efficiency investments.

2. Exploring the Energy Efficiency Potential through Engineering Analysis

In the absence of a comprehensive overview on the existing energy efficiency potential in each sector of the Cypriot economy, we carried out an assessment of firstly the overall existing theoretical and secondly the economically viable energy efficiency potential for the residential and services sectors. In the following paragraphs we describe the methodology applied in order to estimate this potential. Detailed analysis was carried out for residential buildings. In the absence of equally detailed information on buildings of the tertiary sector, we adapted estimates for apartment blocks in order to assess the corresponding energy saving potential of service buildings (mainly offices and hotels).

The maximum theoretical energy saving potential for residential buildings is defined as the amount of current energy use that can be curbed if the existing residential building stock is upgraded to nearly zero energy buildings (nZEB), in line with the provisions of EU and national legislation. On the other hand, the economically viable potential, which is a fraction of the maximum potential, is broadly defined as the amount of energy savings that can be attained if the most cost-effective measures are implemented given some real-world financial constraints that limit the funds available for supporting renovations of residential buildings.

The theoretical energy saving potential has been derived with the aid of Energy Estimation Model for Residential Sector (2EMRS), an in-house model that we had developed in the past and adapted specifically for this study. Using technical and physical input parameters and a dynamic bottom-up algorithm, 2EMRS estimates the final heating and cooling energy use of the existing residential building stock of Cyprus.

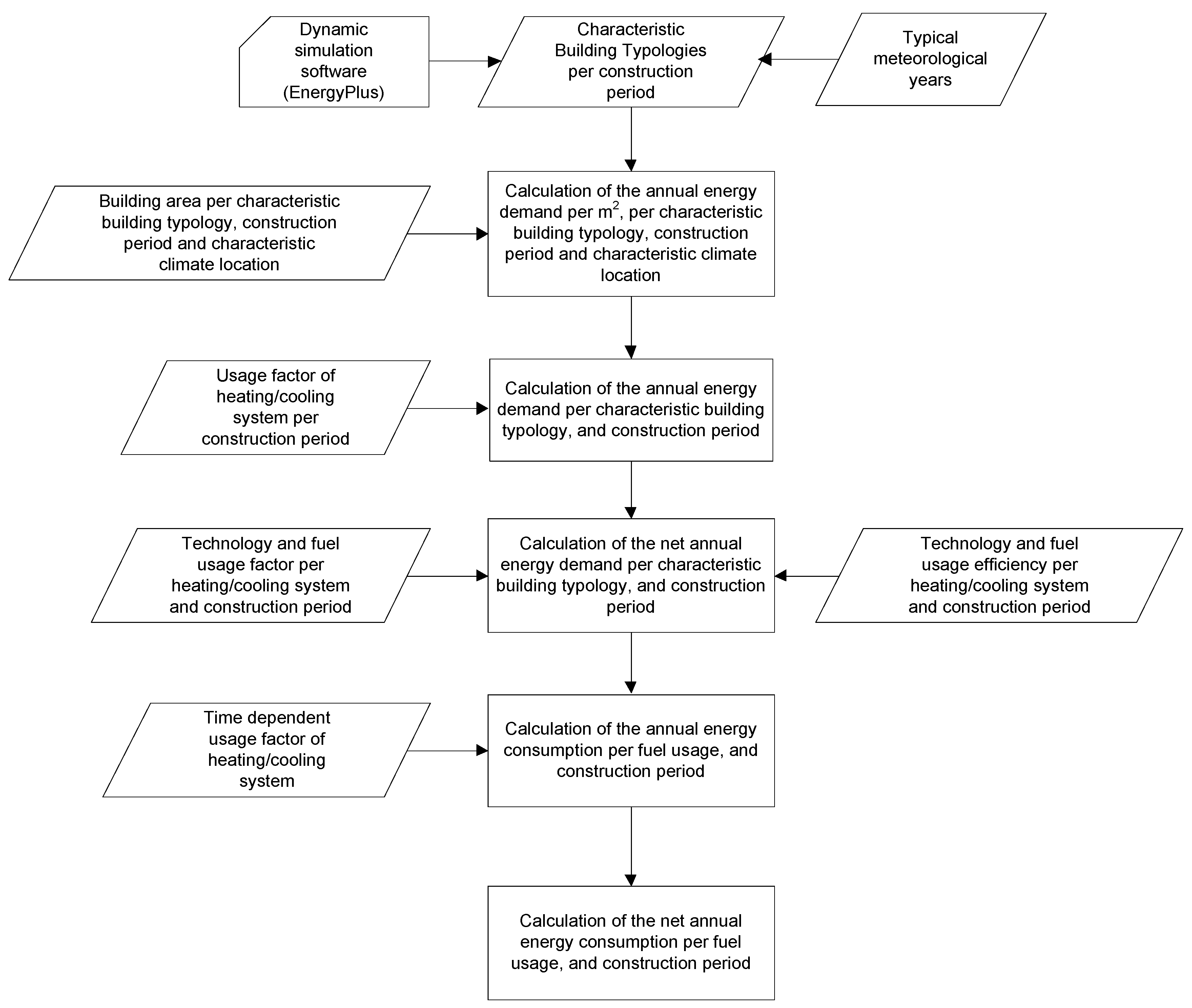

Figure 1 illustrates the 2EMRS calculation algorithm.

The model uses characteristic typologies of buildings in Cyprus; these had been developed by some of the authors in the recent past, after a detailed analysis of the statistics of building construction permits per district and area provided by the Statistical Service of Cyprus (CyStat). This analysis distinguishes into 84 building typologies (the architectural plans of the typical residential buildings are available at

https://3ep.weebly.com/building-typologies-for-cyprus.html (last accessed on 30 November 2017)) based on four building types—single-family house, multi-family house, building with two housing units, and buildings with more than two housing units—, construction period and climatic area; their main characteristics are presented in

Table 1, while

Table 2 illustrates the usage of the main heating technologies in the current building stock of Cyprus, based on the only relevant data that are available for the country.

Climatic data used in the model refer to typical meteorological years. These were extracted from the Meteonorm database and software (which contains climate data from more than 8000 weather stations around the world and provides software that generates representative typical years for any region—

www.meteonorm.com) for the three reference climate regions (hot, moderate and cold) of Cyprus. The hot climate region represents the southern coastal areas of the island, the moderate climate is characteristic for the mainland areas, while the cold region represents the mountainous areas of the island. With the aid of these data, dynamic simulations of the characteristic building typologies were performed using the EnergyPlus software, an acclaimed dynamic energy simulation software primarily used for modelling building energy efficiency [

14], taking into consideration typical indoor conditions and usage patterns, retrieved by previous analysis [

15]. Other input data, as illustrated in

Figure 1, are:

Building area per characteristic building typology, construction period and climatic location. This information has been provided by CyStat based on construction and housing statistics.

The usage factor of heating and cooling systems per construction period, which accounts for the percentage of total building space in which a heating/cooling system is not installed; this was derived from surveys conducted by CyStat.

Technology and fuel usage factor per heating/cooling system and construction period; this factor accounts for the share of each heating/cooling system per construction period on the existing residential building stock of Cyprus. Values for this factor have been based on detailed information (some of it unpublished) provided by CyStat based on their surveys.

Technology and fuel usage efficiency per heating/cooling system and construction period. The efficiency figures of the fuel-based heating and cooling system for all construction periods were derived from studies carried out by the government of Cyprus under the provisions of article 5 of EU Directive 2010/31/EC, as well as from the EN 15316-4-X Standards.

The time-dependent usage factor of heating/cooling systems, which is a correction factor considering the actual use of heating and cooling systems on a daily basis. This factor was estimated based on the results of a final energy use survey of households performed by CyStat in 2009. This factor is assumed to be the same for all building typologies, construction periods and heating/cooling systems.

It is worth noting that overall the 2EMRS model uses statistical data provided or extracted from the surveys or statistics conducted by CyStat, which are the only available survey data in Cyprus. Moreover, the simulations of the characteristic buildings, which were performed with the aid of EnergyPlus, are based on typical patterns that have been validated in a previous analysis [

15].

The results of the 2EMRS model are in very good agreement with aggregate energy use statistics provided by CyStat. They lead to a 2.1% overestimation and a 8.6% underestimation of current final energy use of the entire residential sector for heating and cooling respectively. Keeping in mind that such diverse datasets (comprising meteorological data, physical building characteristics, building statistics, and surveys on the use of energy-consuming equipment and appliances) have been combined in 2EMRS, one can consider the agreement between model calculations and aggregate energy consumption as very satisfactory, hence no further calibration procedure was undertaken in this case. Since 2EMRS is intended for use as a tool to assist decision makers, the reliability of its calculations is a sound basis for selecting the most promising measures to promote energy renovations; it should be noted that verification of such models with aggregate statistical data is a commonly acceptable method in the literature (see e.g., [

16] and the references contained therein). Based on 2EMRS model runs, it was possible to assess the maximum theoretical potential for energy efficiency improvements in the residential sector. This potential was estimated in terms of percentage reduction in: (a) heating energy use, (b) cooling energy use, (c) energy use for domestic hot water production and (d) electricity use for lighting and appliances (white goods).

We assumed energy retrofitting of all building envelopes so that the entire existing stock of buildings in Cyprus is upgraded to nZEB. Furthermore, as regards the technologies used for space heating and cooling, we assumed the gradual penetration of the following equipment in existing buildings:

High efficiency heat pumps for cooling in all buildings.

90% penetration of high efficiency heat pumps and 10% penetration of high efficiency boilers for heating in multi-family buildings, located in urban and rural areas.

80% High efficiency heat pumps and 20% high efficiency boilers for heating in single family buildings located in urban areas.

50% High efficiency heat pumps and 50% high efficiency boilers for heating in single family buildings located in rural areas.

For high efficiency heat pumps, a seasonal coefficient of performance (SCOP) for heating of 6 and a seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER) for cooling of 6.5 were considered. For the high efficiency boilers, which burn LPG, an annual fuel utilization efficiency (AFUE) of 96.5% was assumed.

The maximum theoretical scenario also foresees the replacement of: (a) existing lighting technologies with LED, (b) existing white goods appliances with high efficient ones of category A+++ according to the European energy labelling, as well as the installation of solar thermal systems for hot water production where they currently do not exist; the latter can reduce the existing fossil fuel use by up to 75%.

Apart from 2EMRS model runs, this analysis was also based on the findings of earlier studies conducted by the government of Cyprus [

18]. As a result,

Table 3 illustrates the maximum theoretical energy saving potential for the residential sector. Overall energy savings of 51% are theoretically achievable, with LPG the only fossil fuel remaining in use. A reduction in electricity use of 60% is estimated because of the replacement of many appliances, lights and heat pumps for space heating and cooling with modern one that is much more efficient. Renewable sources (solar thermal for water heating and geothermal for space heating and cooling) are expected to slightly increase their use—although their shares will rise considerably because of the declining total amount of energy use. More detailed results by end use are provided in [

19].

Similarly, for buildings of the tertiary sector, the maximum theoretical energy saving potential is defined as the amount of current energy use that can be saved if the existing building stock is upgraded to nZEB, in line with the provisions of the national legislation, decree 366/2014, (which defines nZEB as a building requiring U-values for energy class A, a maximum consumption of primary energy and at least 25% of the demand to be covered by RES) [

20]. It was estimated in terms of percentage reduction in energy use for heating, cooling, hot water production, lighting and appliances, assuming the gradual penetration of high efficiency heat pumps and boilers. Moreover, demand side management/demand response measures were considered.

Due to the significant diversity of building types, pattern uses, equipment etc. in the tertiary sector, as well as the lack of available data, this analysis relied on the engineering modelling of multi-family residential apartment blocks mentioned above, complemented with in-situ visits of the study team and interviews with the energy managers of large facility owners such as banks, hotels and office blocks; interviews with directors of energy management companies; data provided by local companies that are highly involved with the design, construction and maintenance of facilities; and available data from national energy authorities. Furthermore, replacement of all existing street lights at municipal and community level as well as in motorways was assumed.

Table 4 summarises the results on the maximum theoretical energy saving potential for the service sector per fuel, including street lighting. More detailed information can be found in [

18]. Very substantial energy savings are theoretically possible, of the order of 65% for conventional energy forms, with LPG remaining as the only fossil fuel in use, and a rising contribution of solar energy and heat recovery systems.

3. Financial Constraints of Energy Efficiency Measures

Apart from model calculations and technical possibilities, financial constraints are crucial for determining the number and extent of feasible energy refurbishments. The calculations presented in

Section 2 imply a thorough investment in economy-wide renovations of buildings and equipment, which would however require an unprecedented mobilisation of financial and human resources. Based on cost data available to the authors from the market of Cyprus, the average intervention cost of a deep renovation per average dwelling (i.e., weighted average after considering single family, two-family and multi-family buildings) is estimated at about 65,000 Euros. Assuming that it is technically realistic to consider that 90–95% of all buildings can be renovated (since some buildings are very old and require very substantial re-construction to become nZEB), this leads to a cost of around 14 billion Euros. If all these renovations are to be implemented gradually up to the year 2040, with a residential building stock of about 430,000, this would require annual deep renovations of about 18,600 residential buildings for each year from 2018 to 2040, at a cost of 648 million Euros/year. Similarly, deep renovations in buildings of the service sector would require expenditures of the order of 9 billion Euros in total, leading to annual renovations of about 3500 commercial buildings for each year from 2018 to 2040, at a cost of 409 million Euros/year.

This means that an annual renovation rate of 4.3% of all buildings would be necessary, at a cost of more than one billion Euros per year—accounting for about 5% of the country’s annual GDP. These figures are only theoretically feasible; real-world economic constraints render such a consideration implausible.

To arrive at more realistic estimates of the economically viable energy saving potential, we made use of a recent study for Cyprus [

21]. That study has shown that under a scenario which assumes policies considered by national authorities as ‘particularly appropriate’ for Cyprus, the total expenditure in renovations of residential buildings can reach 450–500 million Euros until 2030. This level of expenditures, including both public and private funds, is considered by national energy authorities as a challenging but realistic prospect for the period up to 2030 and was therefore adopted in this analysis.

As regards buildings of the tertiary sector, ref. [

21] assumed that the corresponding ‘particularly appropriate’ policies for Cyprus would only involve total expenditure in renovations of 7.5–8.0 million Euros until 2030. Such an extremely low amount of expenditures would lead to very low savings and to largely untapped energy efficiency potential. Considering the current and foreseen government expenditures until 2020, in our study an average annual total expenditure for energy efficiency interventions for public and private buildings of the service sector of around 25 million Euros was assumed to be realistic for the period until 2030, i.e., 300–350 million Euros for the entire period.

The above mentioned annual expenditure ceilings were considered as budget constraints in the analysis that will be presented in

Section 4, which assessed the economically viable energy saving potential. In order to proceed to this stage, we first had to clarify the type of energy interventions that can be considered as realistic for the building stock of Cyprus. For this purpose, the following individual measures were considered and simulated with 2EMRS:

- (a)

Insulation of the horizontal elements (roof, ceiling, etc.)

- (b)

Insulation of the vertical elements (reinforced elements, masonry)

- (c)

Installation of shading devices

- (d)

Installation high efficiency windows (frame and glasses)

- (e)

Installation of LED lighting bulbs

- (f)

Use of high efficiency heat pumps

- (g)

Use of solar thermal collectors

- (h)

Use of high efficiency boilers in rural areas

- (i)

Installation of Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS)—which applied only to buildings of the service sector.

To carry out this analysis, both investment costs and energy savings data for each measure are necessary.

Table 5 presents the annual energy savings for the above mentioned energy efficiency measures for the two main types of residential buildings (single-family houses and multi-family apartments), according to the calculations of the 2EMRS model. These figures are averages of the simulation results for different construction periods. Numbers in brackets show the range of energy savings computed by 2EMRS for buildings of different construction periods. This highlights the large variation in potential energy savings that can be attained, depending on building materials and construction practices of the past—although not all of these renovations are technically and economically realistic.

The last column of

Table 5 displays the corresponding costs of each intervention, based on actual market data of Cyprus as obtained through communication of the authors with contractors and importers of building materials and appliances. Buildings of the service sector were assumed to have similar cost and energy saving features with multi-family apartment blocks. Keeping in mind the above mentioned diversity of buildings, since the average single-family building simulated has a floor area of 165 m

2 and the average multi-family building has a floor area of 750 m

2, it is indicative to mention that the data of

Table 5 imply average energy savings of single-family buildings ranging between 7.2 kWh/m

2 (for the windows upgrade) up to 43.6 kWh/m

2 (for the deep renovation). The corresponding energy savings of multi-family buildings range between 1.35 kWh/m

2 (for the ground level insulation) up to 25.1 kWh/m

2 (for the deep renovation). Similarly, investment costs in single-family houses vary between 7.3 Euros/m

2 (for installation of solar water heaters) and 223 Euros/m

2 (for the deep renovation), whereas in multi-family buildings the corresponding costs range between 4.55 Euros/m

2 (for a roof insulation) and 107 Euros/m

2 (for the deep renovation).

Based on the figures of

Table 5, and as already mentioned, the average cost of a deep renovation per dwelling (i.e., the weighted average cost after considering single family, two-families and multi-family buildings) is estimated at about 65,000 Euros, meaning that only about 7700 residential buildings could be fully upgraded until 2030 if the fund ceiling of [

21] had to be adhered to. Obviously, the consideration that only deep renovations should be implemented in the residential sector, apart from being unrealistic in pure technical and market terms, is also non-optimal in cost efficiency terms.

It is easy to deduce when observing

Table 5—but also when making more detailed calculations by building type and construction period—that the ratio of energy savings over the investment cost of specific individual measures is higher than the corresponding ratio of a deep renovation. The determination of the mix of appropriate individual interventions of types (a)–(i) will be described in

Section 4.

4. Indices of Cost-Effectiveness

The previous sections provided a methodological approach for the estimation of the maximum theoretical energy efficiency potential in the residential and service sectors and for the adaptation of this potential into an economically viable one, considering the budget that could be available for such measures. To transform the economically viable potential to a realistic potential, one has to account as well for some market related constraints in order avoid lock-in effects and/or market failures. The latter should be mainly assessed in relation to the capacities of the service providers and construction companies to perform a certain number of annual interventions as well as to the anticipated payback periods for the different end-use sectors.

To contribute to the design of an appropriate energy efficiency policy in the buildings sector, it is useful to rank the potential interventions using different cost-effectiveness metrics. It is also necessary to consider both the private perspective (i.e., that of individual investors who will actually proceed with energy refurbishments) as well as the perspective of public policy (since governments provide a part of the energy efficiency funds and have the broad overview of national energy and environmental objectives). More specifically we considered the following indices from the individual investor’s perspective:

- (1)

The weighted effort in investment cost; this is a qualitative index aiming to compare the level of upfront investment that is needed for various energy efficiency interventions. It can be used in order to evaluate the relative easiness or difficulty of one intervention versus the others in the initial decision for their implementation. The index is calculated by rounding the result of the ratio of the investment cost for each energy efficiency intervention (as shown in

Table 4) and the lowest cost among the interventions under comparison.

- (2)

The nominal index of total investment to achieved annual energy savings.

- (3)

The payback period of the specific interventions, which is calculated by accounting for the initial investment cost and the undiscounted cost savings (due to energy savings) during the lifetime of the intervention. This requires assumptions about the future evolution of retail fuel and electricity prices; as all fossil fuels used in Cyprus are petroleum products, and power generation still depends on oil products too, fuel price projections were made in line with the central scenario (‘New Policies Scenario’) of the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2016 [

22].

- (4)

The Net Present Value of the different energy efficiency interventions and investments, for which a proper discount rate should be selected; in this case a private real discount rate of 8% was selected to reflect the relatively risk-averse behaviour of private investors.

From a social perspective the following indices were used:

- (1)

The avoidance cost index, which expresses the average cost of an intervention for each kWh of energy saved over the lifetime of the measure. The avoidance cost is a benchmarking index that can be used to rank the overall cost efficiency of the various energy saving interventions, considering their anticipated lifetime savings (see e.g., the De-Risking Energy Efficiency (DEEP) project,

https://deep.eefig.eu). The index is calculated by inserting as nominator the initial investment cost of the intervention and as denominator the annual energy savings multiplied by its lifetime. This indicator can also be used inversely in order to indicate a threshold—compared with the mean cost of energy supply—above which an intervention is economically meaningful.

- (2)

The avoided fuel import cost annually and for the lifetime of the investment. This index considers the cost savings in terms of primary energy savings per fuel and per intervention annually and also over the lifetime of the intervention. In order to allow for benchmarking analysis, this index is calculated by assuming the same initial investment for all different energy efficiency interventions and then computing their ratio of total cost savings due to the avoided fuel imports over this fix initial investment.

- (3)

Finally, the Net Present Value was calculated again using a real social discount rate of 5% [

23].

Table 6 and

Table 7 present the calculated mean indices for the proposed interventions for the two main types of residential premises (single family houses and multi-family apartment blocks) and their overall comparison. These calculations rely on cost and energy savings data such as those shown in

Table 5. Note that these indices refer to individual interventions (one per building) and do not consider a combination of interventions to be realised for the same premise/building. Moreover the presented values are the mean figures for buildings of different construction periods. A comparison of the foreseen independent interventions of

Table 6 and

Table 7 reveals that:

Measures for multi-family buildings are by about 30% more cost-effective than those for single-family houses, as exhibited e.g., through the indices of investment cost per kWh, the avoidance cost and the avoided fuel cost;

Targeted individual energy refurbishments (e.g., roof insulation and installation of heat pumps) are far more cost-effective than comprehensive interventions (e.g., deep renovation and upgrade of window frames); the latter consistently display negative net present value and very long payback periods;

Interventions like replacement of electronic appliances and lighting as well as solar water heaters have similar indices for both types of residential buildings.

The above general remarks are quite robust irrespective of the index used. However, a closer look at the figures of

Table 6 and

Table 7 can lead to different conclusions depending on which specific index one observes. Using Net Present Value as the sole decision criterion, for example, excludes these interventions with a negative value—deep renovation, façade and ground insulation, and upgrade of windows. The same holds for those interventions with an avoided fuel import cost below unity. Façade insulation in multi-family buildings, on the other hand, has an almost average performance when indices like the avoidance cost and the investment cost per energy saved are observed, which makes it questionable whether it should be rejected as a viable energy refurbishment option using NPV as the sole criterion. Replacement of light bulbs and appliances has a marginally positive or marginally negative net present value (depending on whether social or private discount rates are used), but it fares above average if evaluated using the investment cost per annual savings index. Heat pumps in multi-apartment buildings fare above average in terms of investment cost per energy saved, but only average when the avoidance cost index is used.

The above examples highlight that prioritizing energy efficiency interventions with the aid of one index alone may be misleading and cause sub-optimal utilization of resources. Cost and energy savings data, after all, are averages which do not capture the variety of all buildings and the heterogeneity of their users. Therefore, when formulating an effective energy efficiency strategy, it is necessary to consult diverse indices and additionally to have good knowledge of real market conditions in the region in which this strategy will be applied.

On the basis of the performed analysis, a reasonable policy advice would be to allocate more financial resources (a) for energy refurbishments of multi-family buildings than for single-family houses; and (b) for those interventions that turn out to be the most cost-effective on the basis of several of the above indices. Even so, however, it is important to keep in mind that implementing comprehensive interventions in multi-family buildings is quite difficult since several apartment owners have to agree on the refurbishment of the whole building. In the recent past, owners of such building types have demonstrated low levels of participation in financial incentive programmes that were supported by the government of Cyprus. Hence it is reasonable to suggest that the resources should be almost equally allocated among single- and multi-family buildings. As regards the type of interventions to be promoted, the replacement of lighting and appliances as well as roof insulation and installation of heat pumps are the measures with the highest cost-efficiency and as such are expected to be more easily adopted and implemented by end-users. Installation of solar thermal water heaters is also a very favourable option but with limited potential since most buildings in Cyprus have already installed such systems. In any case, the analysis shows that these are the interventions to be prioritised through targeted policies.

Based on all the above considerations, we used an iterative procedure in order to come up with a proposal for a realistic and cost-effective energy refurbishment plan in the buildings sector of Cyprus, keeping in mind the budget constraints mentioned in

Section 3: 450–500 million Euros and 300–350 million Euros for residential and service sector buildings respectively up to the year 2030.

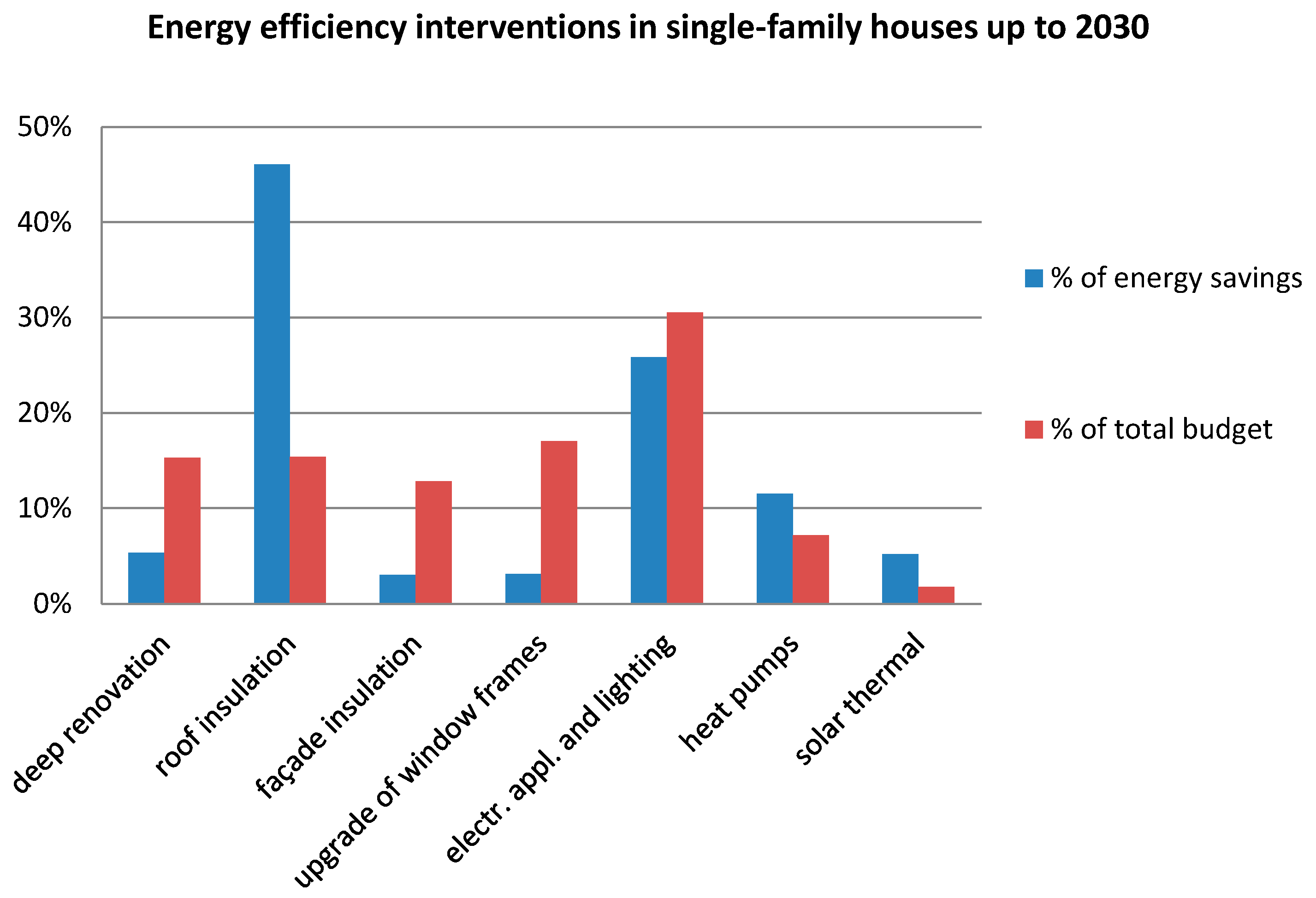

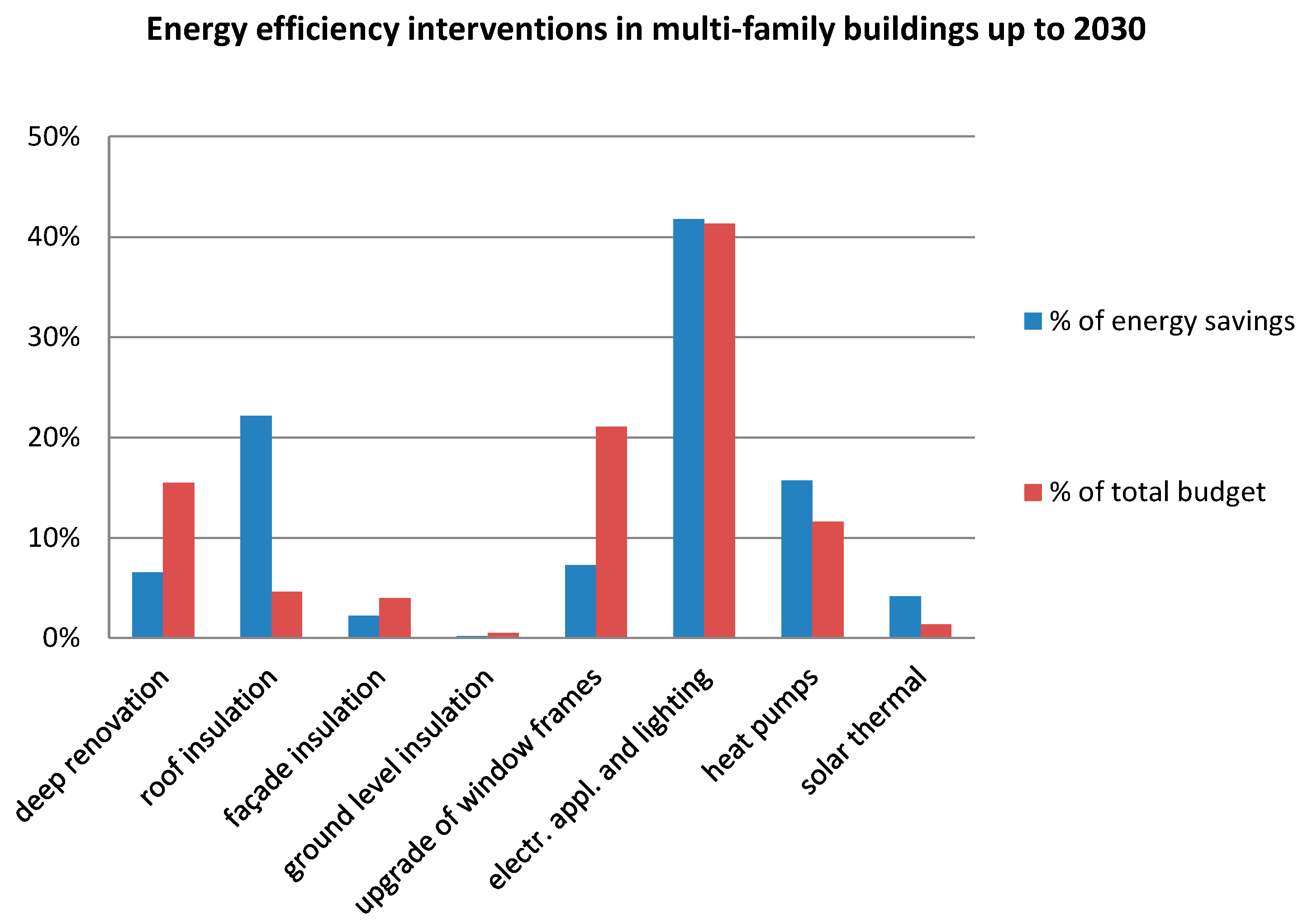

This optimal allocation of interventions in the residential sector, shown in

Table 8, leads to an estimation of around 63,000 households that could proceed to a mix of energy refurbishments until 2030, assuming various shares of households that will undergo single or multiple interventions as well as the most likely mix of these interventions per household. This corresponds to slightly less than 5000 households that could be upgraded energetically every year. One fourth of them are expected to proceed only to substitution of their lighting equipment and appliances and/or to the installation of solar thermal systems. This means that the remaining about 3700 households could undergo significant energy interventions each year, a figure that is realistic since it corresponds to around 1% of the existing number of households. We further considered as a worthwhile investment to allocate around 15% of the funds to some deep renovations which could serve as ‘lighthouse’ projects. This would include all different building typologies: single-family houses up to multi-family blocks of flats.

Taking into consideration the mix of renovations shown in

Table 8 and the corresponding costs of each type of renovation,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the allocation of the available budget to each measure and the corresponding contribution of each measure to total energy savings, for single- and multi-family buildings respectively. From a purely economic perspective, for each renovation type the height of the blue and the red column should be equal; this would imply equal costs per unit of energy saved—which is theoretically the criterion to attain economic efficiency. However, real-world considerations indicate that the cost per kWh cannot be the sole decision criterion:

Consumers are heterogeneous and some of them may not favor specific renovation options (despite their apparent cost-effectiveness) out of risk aversion, lack of information or other reasons;

In some kinds of buildings, actual costs or energy savings may differ from the average values used in our calculations;

Deep renovations seem to be among the economically least favorable options, but they could serve as ‘lighthouse’ projects that could accelerate the introduction of nZEBs at a later stage when encouraged by legislation or cost reductions.

Apart from these considerations, it is clear that priority measures are those which can achieve relatively large savings with a low share of the total budget, i.e., the interventions that have already been mentioned as most favorable: installation of heat pumps and solar thermal heaters, roof insulation, and replacement of lighting equipment.

As regards the allocation of energy renovations to buildings of different construction periods, after considering some market characteristics and the opinion of local stakeholders, we arrived at the following proposal: 4% renovation of the building stock constructed before 1970; 9% renovation of buildings constructed during 1971–1990; 20% renovation of buildings constructed during 1991–2007; and 1% renovation of the most recent buildings (constructed from 2008 up to now). Taking into account the share of different building types and construction periods, as already shown in the last column of

Table 1, the above percentages indicate clearly that the emphasis on renovation should be put on single-family and two-family houses as well as multi-family buildings of the 1991–2007 period, which also account for the largest share of the current building stock. Combining the figures of

Table 3 and

Table 8, the cumulative energy savings for the residential sector result in around 1908 GWh until 2030, with a total avoidance cost of 0.09 €/kWh.

Table 9 presents the resulting cumulative savings by end use.

Under this quasi-optimal mix of energy efficiency interventions for the given budget,

Table 10 presents the realistic energy savings that can be realised in the residential sector. Aggregate energy savings are evidently much lower than the maximum theoretical potential calculations that were presented in

Table 3; the reason is obviously the relatively limited available budget. Oil products and biomass are expected to experience the largest reduction, while electricity savings are assessed to lie close to 5%, like the total energy savings.

The assessment of the cost effectiveness of measures in the service sector was performed using the same methodology with that of the residential sector. Results are similar since most of the measures in buildings of the service sector have similar cost and energy saving features as those of multi-family residential buildings. Nevertheless, additional specific interventions should also be considered for individual sub-sectors that relate to different energy demand profiles and type of energy end-uses. In particular the following interventions are proposed to be considered for Hotels and Lodges, health facilities and shopping malls:

- (a)

Heat recovery from cooling systems

- (b)

Installation of solar thermal collectors

- (c)

Use of solar cooling

- (d)

Use of CHP.

Following the same iterative procedure explained in

Section 3 for residential buildings, and judging also on the basis of real-world considerations about market constraints in Cyprus, we arrived at an estimate of realistic and cost-effective mix of energy efficiency interventions in the service sector. This proposal is presented in

Table 11.

The total number of buildings to undergo energy refurbishments is estimated to be about 10,000 until 2030, or approximately 800 buildings per year. Similarly to residential buildings, 30–40% of the service sector buildings are expected to proceed only with the least expensive interventions with the shortest payback period (installation of solar water heaters and replacement of lighting and appliances) and around 400 buildings per year are estimated to implement a more comprehensive type of interventions and/or one involving higher investment costs. The contribution of each measure in total energy savings and in the total budget is similar to that depicted in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 for residential buildings.

Overall, this mix of interventions can enable realistic energy savings of the order of 6% in the tertiary sector—compared to today’s energy use, plus an additional 2.4% in electricity due to the nationwide replacement of all street lights with more efficient ones. As also mentioned in the case of residential buildings, due to budget constraints the realistic energy saving potential is substantially lower than the theoretical one, which exceeded 60% in the tertiary sector as shown in

Table 4.

It is worth noting that the overall avoidance cost for the service sector’s interventions is essentially equal to that of the residential sector, i.e., 0.09 €/kWh. This means that, without applying explicit optimization methods, our proposal involves similar energy saving costs across the building sector.

Summarising for the total building sector of Cyprus (except industrial buildings that have not been addressed in this paper), the proposed level and allocation of energy efficiency investments will require expenditures amounting to almost 870 million EUR until 2030, with a rather balanced budget distribution—60% for residential buildings and 40% for service sector buildings. With a GDP of around 18 billion Euros in 2016 that is projected to reach 26 billion Euros (at constant prices of year 2015) by 2030, these annual expenditures represent about 0.33% of the annual GDP of Cyprus over the 2018–2030 period, which is considered realistic.

5. Governance Priorities to Implement the Proposed Investments

This section offers some broader suggestions in order to actually implement the mix of interventions proposed on the basis of the indices presented in

Section 4. These recommendations have been formed through communication and data exchange that the authors had with national stakeholders.

To exploit the considerable potential in different sectors, the main barriers preventing a broader uptake of energy efficiency measures—limited financial support and limited interest of final consumers—shall be adequately addressed by governmental authorities in the post-2020 period. The regulatory framework shall be further adjusted in order to establish a secure, consistent and market-oriented framework for energy efficiency interventions in the building sector. The still embryonic state of the energy service market in Cyprus can be attributed to an underdeveloped regulatory framework. More emphasis should be put on issues related to standardization of energy services provided, the performance of such services and their procurement and operation in the public sector.

It is evident from the analysis provided in this paper that the existing energy saving potential should be exploited in a cost-effective manner, allowing the best performing interventions and instruments to scale-up. Existing regulatory provisions with regard to the building code, Energy Performance Certificates, as well as energy audits for non-SMEs should be further enhanced with monitoring procedures in order to create a sustainable regulatory framework for energy efficiency. As the low-hanging fruits for energy efficiency interventions are not fully exploited yet, further emphasis should be given to awareness, training and information activities that would allow the easy attainment of significant energy savings.

The adoption of sectoral post-2020 energy efficiency targets could drive the uptake of energy efficiency interventions in the domestic market, creating at the same time market confidence. A balanced mix of mandatory obligations and voluntary targets for energy consumers and suppliers should be introduced. Moreover, to address market barriers, capacity building measures for various stakeholder groups (e.g., building installers, energy managers, lawyers, bankers) should be timely planned and implemented.

However, the most serious barrier for the achievement of the planned savings is the limited available budget. The private sector has been accustomed to be responsive only when a significant public subsidy is available, while the public sector tends to request full upfront capital coverage. For this reason, the transition to a more market-oriented financial support scheme should be a priority. Government support will continue to play a vital role, but public funds should be dedicated to drive the public financial resources to more cost-efficient support instruments and types of energy efficiency interventions with a higher leverage. The proposed annual investment rate of around 67 million Euros for the 2018–2030 period in order to reach the calculated energy savings is definitely a challenge, both for the national government and for the local market. Hence the activation of various financing tools and mechanisms should be designed carefully and on time, in order to allow the uptake and implementation of all these proposed energy efficiency interventions in buildings.

To this aim, the establishment of a dedicated energy efficiency revolving fund would allow designing a sustainable medium-term national support scheme for energy efficiency interventions. The success of this proposal critically depends on the involvement of the domestic banking sector, hence its active participation in this Fund should be secured from the start. The possibility of additional inflows to this fund (through a carbon tax on non-ETS sectors) could also be considered provided that no fiscal or legal obstacles occur.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Energy refurbishments of buildings can bring about substantial improvements in the energy efficiency of an economy, which can ensure progress towards decarbonisation and contribute to several additional sustainability objectives. Prioritising the most economically promising investments is not straightforward because apart from cost-effectiveness calculations, several real-world constraints have to be taken into account. Ignoring consumer heterogeneity, local market conditions and financial barriers can lead to the ‘energy efficiency gap’ whereby theoretically optimal energy efficiency policies are less effective or more costly when implemented in real life.

In this paper we described an approach to assess the economically viable energy efficiency potential in the building sector of Cyprus, with a combination of detailed engineering modelling, cost-effectiveness calculations and real-world considerations of budgetary, technical, behavioural and market constraints. We relied on an extensive survey of detailed national data, collecting information from the Statistical Service of Cyprus as regards the number, type and size distribution of buildings as well as the share of equipment and fuels for each end use. We also collected data about the costs and efficiency of energy using equipment from the local market; this is important for the reliability of the cost-effectiveness estimates because Cyprus mainly imports equipment and is an island state where most imported building materials and equipment have relatively high transport costs. Therefore, data from EU-wide or international databases were in most cases not directly applicable to Cyprus (see e.g., the EU Buildings Database at

https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/eu-buildings-database; the “Retrofit Solutions Database” of the European INSPIRE project at

http://inspirefp7.eu/retrofit-solutions-database/; data collected in the frame of the European ENTRANZE project at

http://www.entranze.eu/pub/pub-data; diverse data sources available at

http://bpie.eu/focus-areas/buildings-data-and-tools/; or the Odyssee-Mure database [

5] (all websites last accessed on 27 November 2017)).

Comparing our aggregate model results with national energy consumption statistics by fuel, we found them to be in very good agreement. Keeping in mind that our results have been the result of a combination of very diverse datasets, this agreement is very satisfactory and in line with model verification approaches that are applied in the international literature.

We then examined diverse cost-effectiveness indices and came up with a proposal for prioritising specific energy investments such as the installation of heat pumps, insulation of roofs, and replacement of lighting and electronic equipment—without however ignoring other measures that may be economically less favourable but can realistically be implemented in a limited number of buildings. Finally we addressed issues on the governance of energy efficiency policies, focusing on weaknesses of the current regulatory environment in Cyprus. This discussion can be generalised for many other countries facing similar dilemmas—for example, countries with limited public funding resources and limited knowledge by several stakeholder groups; without available micro data on the behaviour of residential consumers and small businesses; or with market particularities (e.g., relatively small sized island states) for which cost data from international databases may not be representative of local conditions.

This study can be enhanced in the future by evaluating ex-post the actual effectiveness of measures in a number of buildings that have been refurbished with one or more of these kinds of energy renovations. Such an evaluation has not been conducted in Cyprus so far and could shed light in the real-world behaviour of users of buildings. Moreover, it would be useful to assess rebound effects which also compromise the energy savings calculated through engineering models. We have not considered any rebound in our assessment, but since the analysis focuses on buildings only, one can reasonably assume that the rebound effect will be similar for different types of renovations in buildings; hence accounting for rebounds, although it would provide more appropriate cost-effectiveness calculations, would hardly change the priorities in energy refurbishments as recommended here.

The empirical approach proposed in this paper cannot be found in energy economics textbooks, nor does it seem to apply the first-best approach; nevertheless it enables a realistic assessment that can lead to the formulation of appropriate energy efficiency strategies. Still, in order to ensure proper implementation of measures in order to realise the identified energy saving potential, further work will have to focus on behavioural issues, taking advantage of experience gained from other countries [

24,

25] and from international collaboration projects [

26]. Especially in residences of less educated people and small commercial enterprises, which overall account for a large portion of the building stock, the successful deployment of energy renovations can play a decisive role for the economy-wide improvement of energy efficiency.