Planning for Community Based Tourism in a Remote Location

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Concerned with the future;

- About acquiring information;

- Anticipating or forecasting change under conditions that are often uncertain;

- The development of a strategic vision;

- The evaluation of different course of action;

- Facilitating political decision making; and

- Value laden and political.

2. Community Based Tourism as Community Development, Community Engagement and as a Planning Process

2.1. Community Based Tourism as Community Development

- Success and survival at the expense of spatial isolation and structural independences;

- Local employment and benefits at the expense of local initiation and control;

- Social status and mobility at the expense of social cohesion and harmony; and

- Incipient environmentalism at the expense of ecological sustainability.

2.2. Community Based Tourism as Community Engagement

- The setting of the vision, goals and objectives;

- The collection and analyses of relevant data and information;

- A public involvement process;

- The evaluation of alternative future scenarios;

- The selection and implementation of a course of action and associated policies;

- The establishment of a monitoring and evaluation process; and

- A feedback mechanism to ensure adaptive management as a response to changing circumstances and new information.

- enhance local socio economic benefits [15];

- increase the limits of local tolerance through participation by locals in the tourism development process [20];

- assist communities to be more responsive to intensifying competition from the globalisation of trade, business and travel [18]; and

- help secure the commitment of local people, without which the sustainable development of tourism is extremely difficult if not impossible [21].

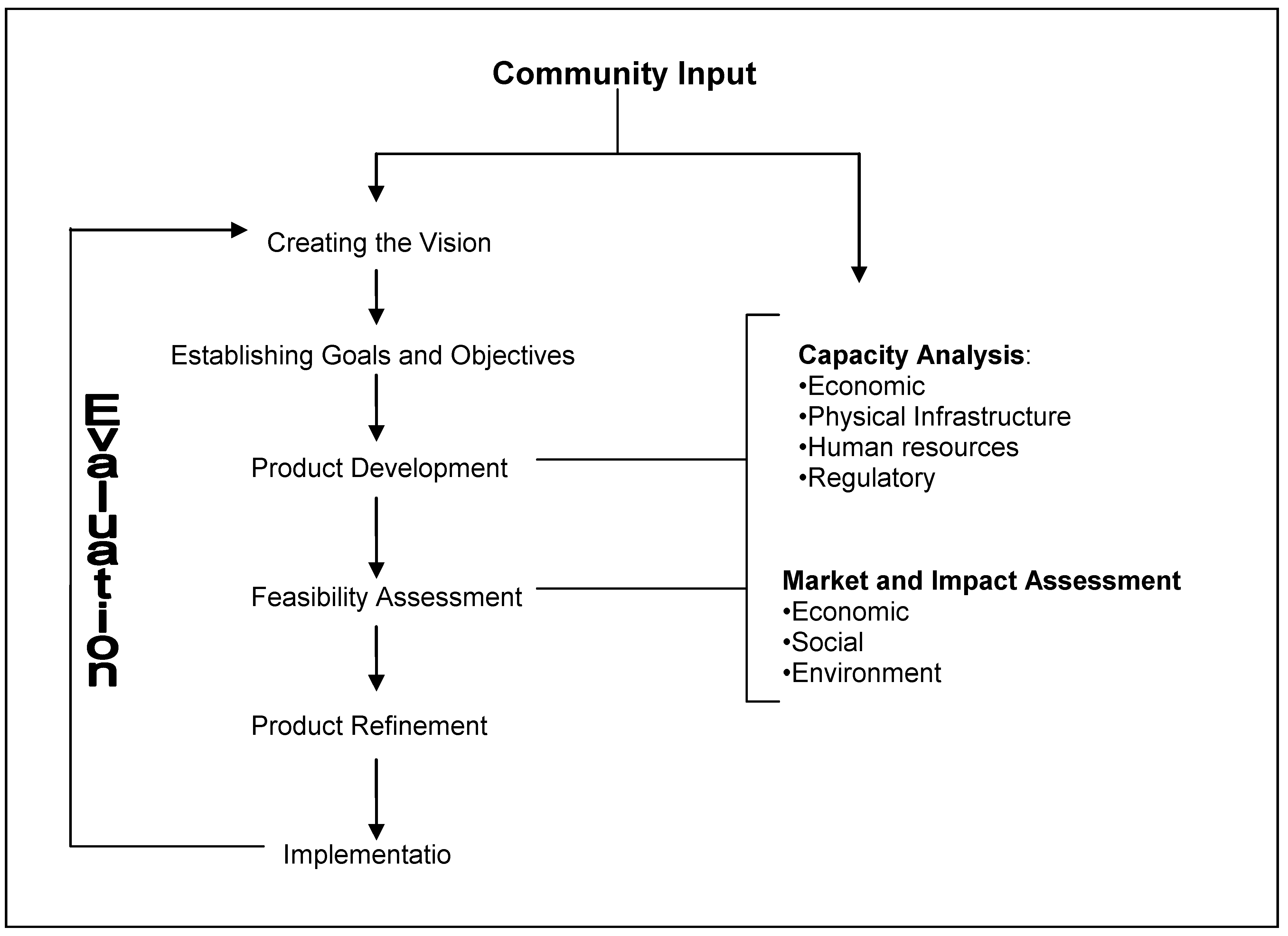

2.3. Community Based Tourism as a Planning Procedure

- The creation of a vision to establish an overall framework for tourism development.

- The setting of goals and objectives to bring that vision about.

- The development of programs designed to accomplish the relevant objectives.

- An evaluation of the feasibility usually financial of the proposed project (if necessary and adaptation or refinement).

- The implementation and ongoing monitoring of the project established as a result of the planning and decision making process.

3. Methods

Case Study Location

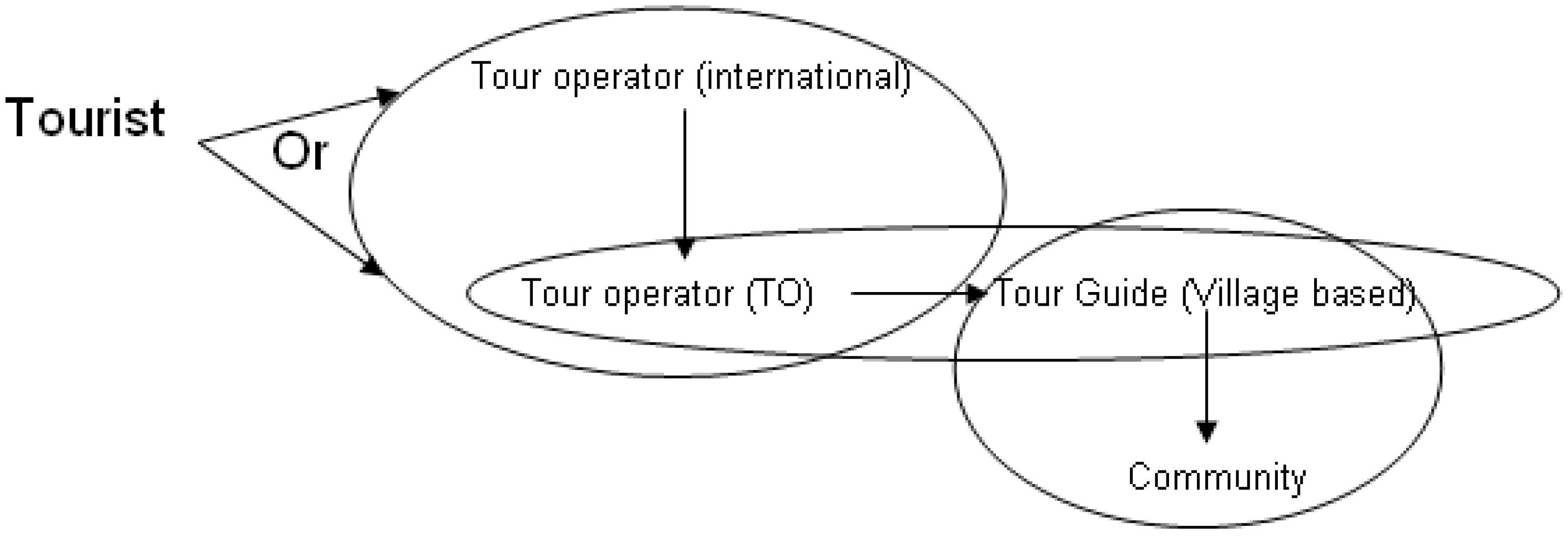

4. Community Based Bird Watching Tourism

4.1. How the Community Became Involved in Tourism

4.2. Decision Making

4.3. Land Use Assessment System

5. Discussion and Conclusions: A New Conceptualization for CBT

Acknowledgements

References

- Markey, S.; Halseth, G.; Manson, D. The struggle to compete: From comparative to competitive advantage in Northern British Columbia. Int. Plan. Stud. 2006, 11, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Jenkins, J. Tourism Planning and Policy; John Wiley and Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yiftachel, O. Essay: Reengaging Planning Theory? Towards South Eastern Perspectives. Plan. Theory 2006, 5, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, G. A Systems View of Planning: Towards a Theory of the Urban and Regional Planning Process; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- De Beer, F.; Marais, M. Rural communities, the natural environment and development—Some challenges, some successes. Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C. Revisiting “community” in community-based natural resource management. Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Community Engagement and Development Booklet; Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources: Brisbane, Australia, 2006.

- Young, I. City Life and Difference. In Readings in Planning Theory 1990; Campbell, S., Fainstein, S., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Edinburgh, UK, 2003; pp. 336–355. [Google Scholar]

- Delanty, G. Community; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lalli, M. Urban Related Identity: Theory, Measurement, and Empirical Findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K. A critical look at community based tourism. Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Community Based Ecotourism: The Significance of Social Capital. Ann. Tourism. Res. 2005, 22, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Promoting women’s empowerment through involvement in ecotourism: Experiences from the third world. J. Sustain. Tourism 2000, 8, 232–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontongeorgopoulos, N. Community Based Ecotourism in Phuket and Ao Phangnga Thailand: Partial Victories and Bittersweet Remedies. J. Sustain. Tourism 2005, 13, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Eagles, P. An Integrative Approach to Tourism: Lessons from the Andes of Peru. J. Sustain. Tourism 2001, 9, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M. Power Relations and Community Based Tourism Planning. Ann. Tourism. Res. 1997, 24, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R. Community driven tourism planning and residents preferences. Tourism Manage. 1993, 14, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Getz, D. Collaboration Theory and Community Tourism Planning. Ann. Tourism. Res. 1995, 22, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macbeth, J.; Carson, D.; Northcote, J. Social Capital, Tourism and Regional Development: SPCC as a Basis for Innovation and Sustainability. Curr. Issue. Tourism 2004, 7, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Manage. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sautter, E.; Leisen, B. Managing Stakeholders: A Tourism Planning Model. Ann. Tourism. Res. 1999, 26, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, J.; Benson, A. Planning for Sustainable Ecotourism: The Case for Research Ecotourism in Developing Country Destinations. J. Sustain. Tourism 2006, 14, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, T.; Nel, E. Tourism as a local development strategy in South Africa. Geogr. J. 2002, 168, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D. Building Community Awareness of Tourism in a Developing Country Destination. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2000, 25, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D. Tourism, Globalisation and Development: Responsible Tourism Planning; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ife, J. Community Development: Community Based Alternatives in an Age of Globalization, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Cranbury, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Politics and Place: An Analysis of Power in Tourism Communities in Tourism in Destination Communities; Singh, S., Timothy, D., Dowling, R., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2003; pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Public Participation Spectrum; International Association for Public Participation: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2007. Available online: http://www.iap2.org/associations/4748/files/Spectrum.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2007).

- Costa, C. An Emerging Tourism Planning Paradigm? A Comparative Analysis between Town and Tourism Planning. Int. J. Tourism Res. 2001, 3, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Assessment Forum—A Leading Practice Model for Development Assessment in Australia; Department of Transport and Regional Services: Canberra, Australia, 2005.

- Low Choy, D.; Worral, R.H.; Gleeson, J.; Mckay, P.; Robinson, J. Environmental Planning Project: Volume 1—Management Framework, Tools and Co-operative Methods; Technical Report; CRC for Coastal Zone Estuary and Waterway Management: Sydney, Australia, 2002; Volume 4, p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvberg, B. Five Misunderstanding about Case Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, P. Social Change in Melanesia: Development and History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Iso Ahola, S. The Social Psychology of Leisure and Recreation; WCB Company Publishers: Houston, TX, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: A literature review with implications for tourism planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2004, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an Open Access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Harwood, S. Planning for Community Based Tourism in a Remote Location. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1909-1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2071909

Harwood S. Planning for Community Based Tourism in a Remote Location. Sustainability. 2010; 2(7):1909-1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2071909

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarwood, Sharon. 2010. "Planning for Community Based Tourism in a Remote Location" Sustainability 2, no. 7: 1909-1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2071909