Shopping for Society? Consumers’ Value Conflicts in Socially Responsible Consumption Affected by Retail Regulation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Value Conflicts in Socially Responsible Consumption

2.2. Growth of Large Retailers and Government Regulation

3. Methodology

3.1. Concourse Development

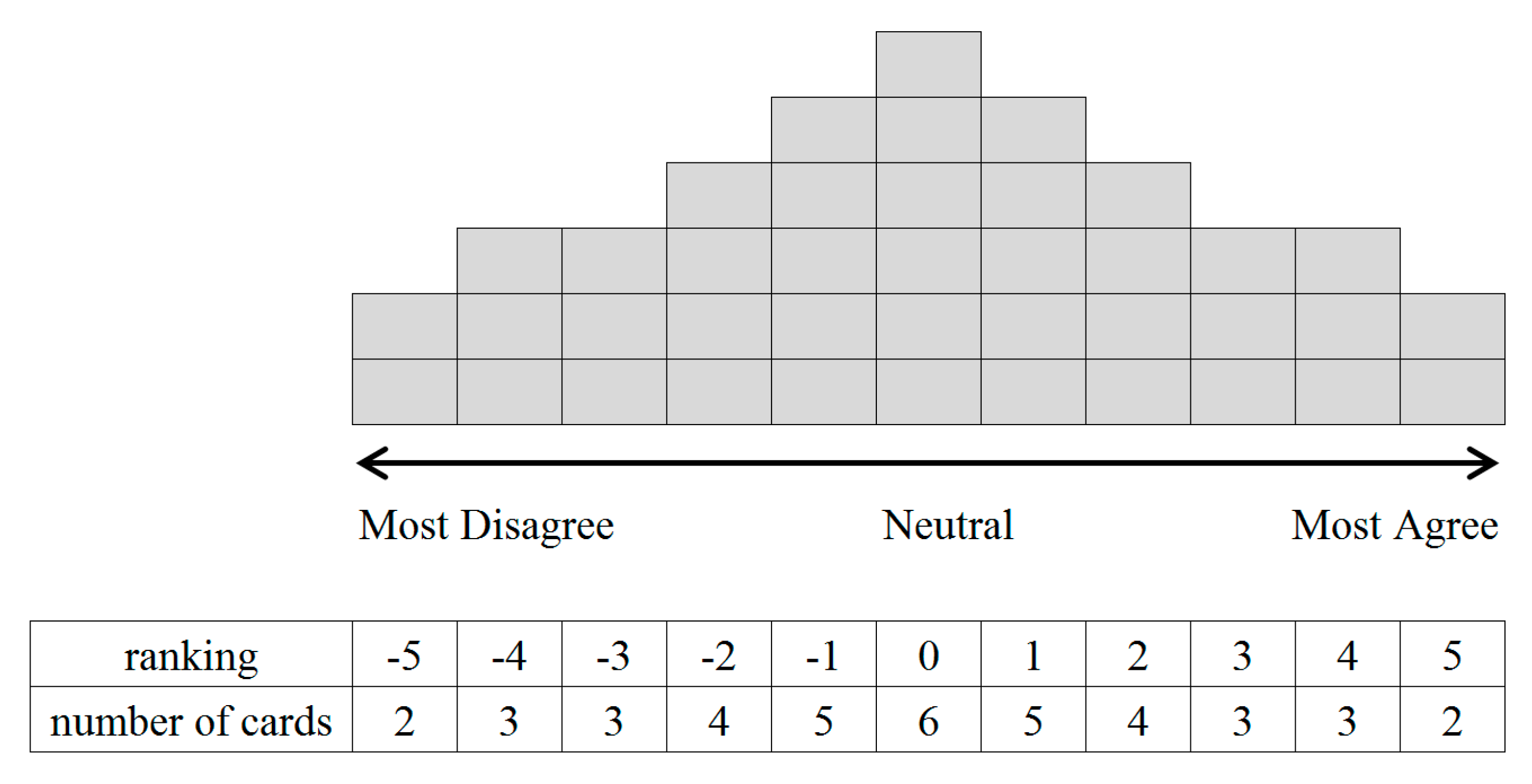

3.2. Setting Up the Q-Set

3.3. Selection of the P-Set

3.4. Q-Sort

3.5. Q Factor Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Factor Description

4.1.1. Group 1: Ethical Conformist—“We Should All Live Together”

“It’s only two days a month! Anyone who wants to shop in a large store can go for the remaining 28 days. There is actually not much inconvenience.”(ID #13)

“I think regulation of large retailers is in line with current trends. The past was an achievement-oriented era, but now the value of relationships, harmony, and co-prosperity is much more important. So, I think it is desirable for capitalism to actively intervene and to promote the balanced development of society.”(ID #19)

“In the long run, if traditional markets are encouraged, they will be a good place to host local festivals or to introduce local culture.”(ID #30)

4.1.2. Group 2: Market Liberalist—“Let the Wallet Work for Itself”

“It is a pity that the powerless are lagging behind. However, I think that small stores should try their best to provide better products and services to survive the competition.”(ID #3)

“Does it make sense that the government prevents me from shopping at the time and place I want in a liberal state? I am upset when a hypermarket is closed because of regulations, particularly on the weekend.”(ID #21)

“I think it is not a good idea to restrict the shopping behavior of general consumers to protect a certain group. This compulsive approach will reduce the benefits for consumers.”(ID #20)

4.1.3. Group 3: Ambivalent Bystander—“It’s a Good Policy in Principle, But Not for Me”

“I understand the necessity of regulating large retailers and agree that it is an inevitable policy. But I don’t think this is an important issue for which to change my shopping habits.”(ID #6)

“I am in favor of this regulation. The state has an obligation to protect the underprivileged. Even so, if a large retailer is cheap and convenient to use, I will just continue to use them.”(ID #29)

4.1.4. Group 4: Internally Conflicted—“Seems Like I’m Doing Something Wrong...”

“Of course, I don’t want anyone to restrict my shopping behavior. But I cannot say that I oppose the government policy, which was implemented for good purposes, especially in my position as a public official.”(ID #2)

“To be honest, I oppose this policy because it makes me conflicted with regard to everyday grocery purchases. I feel bad when I shop at a hypermarket because I seem to be a selfish person”(ID #28)

4.2. Similarities and Differences Between Perspectives

4.3. Store Choice Behavior Across Different Consumer Groups

5. Discussion and Implications

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luchs, M.G.; Miller, R.A. Consumer Responsibility for Sustainable Consumption. Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 254–266. ISBN 978 1-783-126-3. [Google Scholar]

- Devinney, T.M.; Auger, P.; Eckhardt, G.; Birtchnell, T. The Other CSR: Consumer Social Responsibility; Leeds University Business School Working Paper; 2006; Volume 15, pp. 1–12. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.901863 (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Pigors, M.; Rockenbach, B. Consumer social responsibility. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 3123–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scourfield, P. Are there reasons to be worried about the ‘caretelization’ of residential care? Crit. Soc. Policy 2007, 27, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, J. Looking at consumer behavior in a moral perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 51, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lai, I.K. The ethical judgment and moral reaction to the product-harm crisis: Theoretical model and empirical research. Sustainability 2016, 8, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.; Johns, N.; Kilburn, D. An exploratory study into the factors impeding ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer–do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingen, J.; Sage, J.; Sirieix, L. Consumer coping strategies: A study of consumers committed to eating local. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tienhaara, A.; Ahtiainen, H.; Pouta, E. Consumer and citizen roles and motives in the valuation of agricultural genetic resources in Finland. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 114, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, M.J.; McEachern, M.G. Consumer value conflicts surrounding ethical food purchase decisions: A focus on animal welfare. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2004, 28, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.R. Q methodology and qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.G.; Yang, Z. The effect of uncertainty avoidance and social trust on supply chain collaboration. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.H. Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: the role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozar, J.M.; Hiller Connell, K.Y. Socially and environmentally responsible apparel consumption: Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Soc. Respon. J. 2013, 9, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, S.M.; Winer, R.S. The role of the beneficiary in willingness to pay for socially responsible products: A meta-analysis. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Chatzidakis, A. Consumer social responsibility (CnSR): Toward a multi-level, multi-agent conceptualization of the “other CSR”. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisander, J. Motivational complexity of green consumerism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L. Locating the “politics” in political consumption: A conceptual map of four types of political consumer identities. Int. J. Commun. 2015, 9, 2047–2066. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, G.T.M. Market-focused sustainability: Market orientation plus! J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaile, M.P.; Klein, K.; Böck, W. From bounded morality to consumer social responsibility: A transdisciplinary approach to socially responsible consumption and its obstacles. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, F.E. Determining the characteristics of the socially conscious consumer. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, S.C.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, E.Y. The role of perceived consumer effectiveness and motivational attitude on socially responsible purchasing behavior in South Korea. J. Glob. Mark. 2012, 25, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Hutter, K. Carrotmob as a new form of ethical consumption. The nature of the concept and avenues for future research. J. Consum. Policy 2012, 35, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezabakhsh, B.; Bornemann, D.; Hansen, U.; Schrader, U. Consumer power: A comparison of the old economy and the Internet economy. J. Consum. Policy 2006, 29, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J. The citizen-consumer hybrid: Ideological tensions and the case of Whole Foods Market. Theory Soc. 2008, 37, 229–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention–behavior gap. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Shiu, E. Ethics in consumer choice: A multivariate modelling approach. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, L.; Davies, I.A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bakker, E.; Dagevos, H. Reducing meat consumption in today’s consumer society: Questioning the citizen-consumer gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2012, 25, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, L.J.; Mayo, M.A. An empirical test of a model of consumer ethical delimmas. Adv. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 720–728. [Google Scholar]

- Culiberg, B.; Bajde, D. Do you need a receipt? Exploring consumer participation in consumption tax evasion as an ethical dilemma. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory-Smith, D.; Smith, A.; Winklhofer, H. Emotions and dissonance in ‘ethical’consumption choices. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1201–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, L.; Miles, M.P.; Grimmer, M. The performance advantage of business planning for small and social retail enterprises in an economically disadvantaged region. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2016, 10, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; McMaster, R.; Newholm, T. Care and commitment in ethical consumption: An exploration of the ‘attitude–behaviour gap’. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, D.R.; Schwartz, D. The value of capstone projects to participating client agencies. J. Public Aff. Educ. 2009, 15, 445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Amason, A.C.; Schweiger, D.M. Resolving the paradox of conflict, strategic decision making, and organizational performance. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 1994, 5, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.C.; Wang, C.C.F. Collectivism, corporate social responsibility, and resource advantages in retailing. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltiwanger, J.; Jarmin, R.; Krizan, C.J. Mom-and-pop meet big-box: Complements or substitutes? J. Urban Econ. 2010, 67, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koske, I.; Wanner, I.; Bitetti, R.; Barbiero, O. The 2013 update of the OECD’s database on product market regulation. OECD Econ. Dep. Work. Pap. 2015, 1200, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Report on Regulatory Reform, Volume II, Thematic Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Boylaud, O.; Nicoletti, G. Regulatory reform in retail distribution. OECD Econ. Stud. 2001, 2001, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Hallsworth, A.G. Tesco in Korea: Regulation and retail change. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2016, 107, 207–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korean Chainstores Association. The Yearbook of Retail Industry; Korean Chainstores Associations Press: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs, J.E.; Rindfleisch, A. Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 348–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, J.Q. Consumerism versus producerism: A study in comparative law. Yale Law J. 2007, 117, 340–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F.; Kok, K.; Beers, P.J.; Veldkamp, T. Assessing Sustainability Perspectives in Rural Innovation Projects Using Q Methodology. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraak, V.I.; Swinburn, B.; Lawrence, M.; Harrison, P. AQ methodology study of stakeholders’ views about accountability for promoting healthy food environments in England through the Responsibility Deal Food Network. Food Policy 2014, 49, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijnik, M.; Nijnik, A.; Bergsma, E.; Matthews, R. Heterogeneity of experts’ opinion regarding opportunities and challenges of tackling deforestation in the tropics: A Q methodology application. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2014, 19, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppen, E.; Breukers, S.; Hisschemöller, M.; Bergsma, E. Q methodology to select participants for a stakeholder dialogue on energy options from biomass in the Netherlands. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmolck, P. PQMethod (Version 2.35). Computer Software, 2002. Available online: http://schmolck.userweb.mwn.de/qmethod (accessed on 15 August 2015).

- Donner, J.C. Using Q-sorts in participatory processes: An introduction to the methodology. Soc. Dev. Pap. 2001, 36, 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A.S.; Fein, S.B.; Schucker, R.E. Performance characteristics of seven nutrition label formats. J. Public Policy Mark. 1996, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, S.A. Good Intentions, Questionable results: A critical analysis of the shutdown of large retailers in South Korea. Aust. J. Asian Law 2015, 16, 1–20. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2627509 (accessed on 20 March 2016).

- Miller, M.J.; Sendrowitz, K.; Connacher, C.; Blanco, S.; de La Pena, C.M.; Bernardi, S.; Morere, L. College students’ social justice interest and commitment: A social-cognitive perspective. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 56, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The big idea: Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 89, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Factor Loading | Gender | Age | Income (Million Won) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| Group 1 (n = 9) | 13 | 0.8007X 1 | −0.1244 | 0.1937 | −0.0053 | F | 31 | 350 |

| 27 | 0.7703X | −0.2225 | 0.1134 | 0.0162 | F | 35 | 370 | |

| 14 | 0.7352X | −0.4380 | 0.2125 | −0.1607 | F | 33 | 450 | |

| 30 | 0.7046X | 0.0972 | −0.2904 | 0.2579 | M | 35 | 180 | |

| 25 | 0.6932X | −0.1099 | 0.0336 | −0.0978 | M | 38 | 200 | |

| 19 | 0.6888X | −0.5670 | −0.0366 | −0.0052 | M | 41 | 420 | |

| 5 | 0.6823X | −0.2189 | 0.2207 | 0.0116 | M | 39 | 700 | |

| 9 | 0.6324X | −0.3180 | 0.3981 | −0.1929 | F | 31 | 350 | |

| 16 | 0.5361X | 0.1867 | 0.1423 | 0.3691 | F | 34 | 350 | |

| Group 2 (n = 11) | 7 | −0.1042 | 0.7467X | 0.1760 | 0.0874 | M | 36 | 500 |

| 22 | −0.1129 | 0.7395X | 0.2745 | 0.0214 | M | 40 | 650 | |

| 17 | 0.1830 | 0.7324X | −0.0272 | 0.2546 | F | 33 | 250 | |

| 23 | −0.4572 | 0.6959X | −0.0126 | 0.2114 | M | 33 | 300 | |

| 3 | −0.0322 | 0.6941X | 0.0071 | 0.0912 | M | 37 | 450 | |

| 24 | −0.5470 | 0.6623X | 0.0958 | 0.0356 | M | 37 | 400 | |

| 21 | −0.3993 | 0.6331X | −0.0797 | 0.0255 | M | 37 | 700 | |

| 12 | 0.1203 | 0.5881X | 0.2451 | 0.0390 | F | 31 | 280 | |

| 20 | 0.3599 | 0.5740X | −0.0579 | 0.3387 | F | 34 | 430 | |

| 10 | −0.0316 | 0.5530X | −0.1122 | 0.1239 | F | 34 | 300 | |

| 15 | 0.1829 | 0.4120X | 0.2252 | 0.0152 | F | 33 | 500 | |

| Group 3 (n = 4) | 11 | 0.2154 | −0.0301 | 0.7989X | 0.2503 | F | 32 | 600 |

| 29 | 0.1242 | 0.4047 | 0.7457X | 0.1406 | F | 30 | 150 | |

| 18 | 0.3496 | 0.0436 | 0.6821X | 0.1954 | F | 34 | 200 | |

| 6 | 0.4660 | −0.0101 | 0.6506X | 0.0645 | M | 35 | 300 | |

| Group 4 (n = 5) | 8 | −0.0642 | −0.1203 | 0.3182 | 0.7730X | M | 43 | 450 |

| 28 | 0.0075 | 0.3884 | 0.0447 | 0.6609X | F | 33 | 300 | |

| 26 | 0.3137 | 0.2289 | −0.1505 | 0.6573X | M | 37 | 450 | |

| 2 | −0.2112 | 0.1512 | 0.1604 | 0.6492X | F | 36 | 300 | |

| 1 | −0.0046 | 0.0974 | 0.1523 | 0.5677X | M | 39 | 220 | |

| Confounded (n = 1) | 4 | −0.1597 | 0.4512 | 0.4739 | 0.3542 | M | 40 | 450 |

| Eigen values | 8.084 | 6.001 | 2.101 | 1.913 | ||||

| Explained variance | 20% | 20% | 10% | 10% | ||||

| No. | Q Statements | Factor Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | I am positive about the regulation of large retailers because it protects small stores and local markets. | 5 | −2 | 1 | −4 |

| 2 | I am positive about the regulation of large retailers because it guarantees workers’ right to rest. | 3 | 0 | 0 | −5 |

| 3 | I am negative about the regulation of large retailers because it encroaches upon consumers’ right of choice. | −3 | 3 | −3 | 0 |

| 4 | I am negative about the regulation of large retailers because it makes consumers’ lives more inconvenient. | −2 | 4 | −1 | 0 |

| 5 | Consumers should understand the social value of co-existence and shared growth pursued by regulation of large retailers. | 2 | −2 | 0 | −3 |

| 6 | Consumers should consider the sustainable development of society in everyday consumption. | 1 | −1 | −2 | 0 |

| 7 | The choice of retail stores is entirely free for individual consumers. | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 8 | Maximizing utility in a given budget is the ultimate goal of consumption. | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| 9 | In fact, I don’t care much for the regulation of large retailers. | −2 | −1 | 3 | 3 |

| 10 | Since the implementation of large retailer regulations, I feel uncomfortable shopping in large retailers. | 0 | −4 | −4 | −1 |

| 11 | Although I generally agree with the need to regulate large retailers, I don’t want to shop in traditional markets or “mom-and-pop” stores. | −1 | 0 | −5 | −1 |

| 12 | I am positive about the regulation of large retailers because it prevents the tyrannies of large corporations. | 5 | −4 | 3 | 0 |

| 13 | I am positive about the regulation of large retailers because it prevents wastes of energy. | 0 | −4 | 1 | 0 |

| 14 | I am negative about the regulation of large retailers because it results in price increases. | −3 | 1 | −2 | −1 |

| 15 | I am negative about the regulation of large retailers because it reduces local employment. | 0 | 1 | −1 | −2 |

| 16 | As members of the local community, consumers should accept some inconvenience from the regulation of large retailers. | 2 | 0 | −1 | −2 |

| 17 | On the days of the mandatory closures of large retailers, it is desirable to shop in traditional markets or “mom-and-pop” stores. | 3 | −3 | 1 | 2 |

| 18 | In a capitalist society, it is inevitable that a decline in traditional markets and “mom-and-pop” stores results from competition in the market. | −2 | 2 | 0 | −2 |

| 19 | Even if the regulation of large retailers is actually effective, it is unfair for consumers to make sacrifices for this. | −2 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 20 | Although I generally agree with the need to regulate large retailers, I can’t stand any inconvenience caused by such regulation. | 0 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| 21 | When purchasing a few items, I feel conflicts regarding whether I shop in a large retailer or a small local store. | 0 | −3 | −4 | 4 |

| 22 | I am positive about the regulation of large retailers because a fair competition between large retailers and small local stores is virtually impossible. | 4 | −1 | 1 | 0 |

| 23 | The regulation of large retailers is a necessary policy for a better society. | 4 | −1 | 2 | 1 |

| 24 | I am negative about the regulation of large retailers because it goes against market trends. | −5 | 3 | 0 | −4 |

| 25 | I am negative about the regulation of large retailers because it is excessive government market intervention. | −3 | 4 | 0 | −3 |

| 26 | The regulation of large retailers does not have any influences on me. | −1 | −5 | 2 | 1 |

| 27 | The regulation of large retailers is meaningful for consumers to practice their social responsibilities. | 2 | −2 | 2 | 0 |

| 28 | Even if the growth of large retailers has a negative impact on society, it is reasonable to shop in large retailers if prices or services are better than small local stores. | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 29 | Even if I am willing to shop in small local stores instead of large retailers, it is difficult to put it into practice. | 0 | 0 | −3 | 3 |

| 30 | I oppose the regulation of large retailers, but I’m reluctant to say that to other people. | −4 | −1 | −5 | 2 |

| 31 | Regulatory policies for large retailers will be beneficial to consumers in the long run. | 4 | −2 | 0 | −2 |

| 32 | The regulation of large retailers is a good policy. | 3 | −3 | 1 | −4 |

| 33 | The regulation of large retailers will become an obstacle to strengthening competitiveness of small local stores. | −4 | 1 | −2 | 2 |

| 34 | Even if constrained by law, large retailers will continue to penetrate local markets. | −4 | 2 | −2 | −1 |

| 35 | Beyond pursuing personal satisfaction, consumers have a responsibility to consider the impact of their consumption behavior on society. | 2 | 1 | −1 | 2 |

| 36 | If large retailers offer products and services desired by consumers, they should be commended rather than regulated. | −1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 37 | Since the implementation of large retailer regulations, I find it more difficult to choose a retail store. | −1 | 0 | −4 | −1 |

| 38 | The regulation of large retailers should be strengthened further. | 1 | −5 | −1 | −5 |

| 39 | The regulation of large retailers should be completely abolished. | −5 | 0 | −3 | −3 |

| 40 | I don’t want to associate the survival of small store owners with my consumption life. | −1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 1 | |||

| Factor 2 | −0.374 | 1 | ||

| Factor 3 | 0.401 | 0.193 | 1 | |

| Factor 4 | 0.006 | 0.352 | 0.366 | 1 |

| Operated by | Store Format | Group 1: Ethical Conformist | Group 2: Market Liberalist | Group 3: Ambivalent Bystander | Group 4: Internally Conflicted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pf 1 | pa 2 | pf | pa | pf | pa | pf | pa | ||

| large corporations | hypermarket | 2.3 | 18.9 | 4.1 | 43.7 | 2.0 | 17.0 | 4.8 | 46.1 |

| SSM | 1.4 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 10.4 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 4.1 | |

| convenience store | 4.0 | 3.2 | 16.8 | 9.5 | 12.0 | 5.7 | 9.0 | 3.6 | |

| self-employed | traditional market | 5.4 | 21.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 13.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| “mom-and-pop” store | 9.6 | 23.9 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 12.0 | 30.0 | 7.0 | 5.6 | |

| others | online and mobile | 2.8 | 13.1 | 6.3 | 23.0 | 4.0 | 15.0 | 2.4 | 4.8 |

| Total | 83.4 | 90.1 | 82.7 | 64.2 | |||||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-M.; Kim, H.-J.; Rha, J.-Y. Shopping for Society? Consumers’ Value Conflicts in Socially Responsible Consumption Affected by Retail Regulation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111968

Lee J-M, Kim H-J, Rha J-Y. Shopping for Society? Consumers’ Value Conflicts in Socially Responsible Consumption Affected by Retail Regulation. Sustainability. 2017; 9(11):1968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111968

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jin-Myong, Hyo-Jung Kim, and Jong-Youn Rha. 2017. "Shopping for Society? Consumers’ Value Conflicts in Socially Responsible Consumption Affected by Retail Regulation" Sustainability 9, no. 11: 1968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9111968