1. Introduction

The ‘Agriculture of the Middle’ (AotM) development model emerged as a response to the ‘bifurcation’ of farms in the US [

1], referring to an increasing number of large scale producers supplying commodity markets on one hand and a growing number of smaller scale producers supplying specialised markets on the other. Mid-size farms that have neither sufficient scale nor efficiency to supply commodity markets nor the required market differentiation strategies to supply specialised markets are decreasing in number and their long-term survival is under threat [

1,

2]. The AotM research and development agenda, involving academic, extension and policy efforts, aims to address the vulnerability of ‘middle’ farms that fall between viable markets. The rationale underpinning the AotM agenda is that ‘middle’ family farms have valuable sustainability attributes that are worth protecting for society, which is discussed at length elsewhere in the literature [

3,

4,

5].

The AotM development model incorporates a two-strand strategy to improve the viability of middle farms. The first strand is to brand family farm products to express the socio-cultural and ecological sustainability values associated with family farms [

6,

7], thereby creating a differentiated product, targeted at premium non-commodity markets [

8]. Secondly, AotM proposes co-operation between family farms to create efficiencies, scale and coordination in accessing markets. In addition, co-operation is also proposed between farmers and other actors, including processors, retailers and consumers, achieved by collective organisation into a values-based supply chain (VBSC) [

9]. VBSCs aim to combine shared vision, information, achieve high performance and trust while adhering to principles of “equitable profits, equitable wages, and business agreements of appropriate extended duration” for all partners in the chain [

9] (p. 120). There is a mutually reinforcing relationship between chain partners’ commitments to fairness and equity and the socio-cultural and ecological sustainability values embodied by food products produced and consumed by the chain [

9].

For farmers operating alone, the co-operative model is typically necessary to facilitate participation in VBSCs. Individual farms often do not have sufficient scale [

10,

11] to partner with large entities, such as processors and retailers in VBSCs, so they must act collectively. Co-operatives are argued to be flexible business models, compatible with the principles of provenance and equitable governance as advocated by VBSCs [

12]. Co-operative values are compatible with the values of the ‘ethical consumer’ who seeks produce that has genuine and traceable links with producers and who desires that their purchases directly benefit producers [

13,

14]. VBSCs are hypothesised to cater for the values of the ethical consumer while supporting the continuation of family farms [

8,

13,

15].

This paper presents a case study analysis involving qualitative ethnographic field research with beef co-operative members and representatives of VBSC partners, including processors and retailers. We utilise a framework of farm-level viability, sustainability and resilience [

5] as an analytical tool to investigate impacts of membership of a co-operative integrated to a VBSC at farm-level. Our analysis suggests that the integration of a co-operative model to a VBSC had positive impacts on members’ viability, sustainability and resilience. Notwithstanding such successes, the co-operative and its VBSC experienced challenges. Political issues and power struggles within the VBSC led to membership loss in the co-operative and threatened its founding principles and long-term success.

2. Farm Viability, Sustainability and Resilience

Family farms are threatened with low economic viability and, in the European Union (EU) for example, are often dependent on subsidies to survive [

4,

16,

17,

18]. Fundamental to measuring viability are economic measurements such as Family Farm Income (FFI). FFI varies according to factors such as farm size, enterprise specialisation, productivity, policy changes, market prices, the availability of other income sources, and the stage in the lifecycle of the farm operator [

19,

20]. Farm viability is determined by the ability of a farm to earn the average agricultural wage for family labour in addition to providing a 5% return on non-land assets [

21].

While many agricultural development blueprints emphasise the need for farms to achieve greater scale and increase the volume of product in order to improve farm viability, [

6] (p. 3) highlight that viability is not wholly determined by scale but instead by market structures. They categorise the problem as:

“Not scale-determined, it is scale-related. That is, farms of any size may be part of the market that falls between the vertically integrated, commodity markets and the direct markets.”

With reference to the US context, [

6] discuss the growing ‘bifurcation’ between the cohort of large scale farms producing commodity products on one hand and the cohort of smaller scale farms involved in the specialist food sector on the other. Accompanying this bifurcation is a loss of family farms that are neither large enough nor specialised enough to compete in either market [

1]. Authors [

6] and [

1] cite [

22] who state that there are two main routes towards competitiveness in a global economy, and while ‘not impossible, it is difficult to do both’ [

2] (p. 13). The first is to be a low-cost supplier of an undifferentiated commodity product and the second is to produce a unique differentiated quality product. Farms in the US, that occupy the perilous middle-ground between these two bifurcated market strategies, have seen farm numbers and farm viability drastically decline [

2]. There is evidence of an embryonic parallel bifurcation in the Irish context [

23]. However, it is also evident that despite many family farms falling into the category of economically ‘unviable’, many are reluctant to cease operating [

24]. This draws our focus to factors other than economic viability in determining the continuation of family farming, such as sustainability and resilience.

Sustainability can be simply defined as an attempt to balance economic, social and environmental goals [

5,

25,

26]. It is widely acknowledged that the family farm model supports the achievement of agricultural sustainability [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The sustainability agenda is broad, encompassing multiple environmental, social and economic dimensions and therefore measurement of sustainability can be problematic [

33,

34]. Due to the plethora of sustainability definitions that exist, and variations in interpretation, the meaning of sustainability can often be rendered ‘bland’ [

35]. However, methodologies to measure sustainability are evolving and indicators have been developed that incorporate economic, environmental, social and innovation dimensions of sustainability [

34,

36].

Furthermore, recent international policies such as the EU’s European Innovation Partnership (EIP) have taken a more focused approach to the importance of social capital and networks in rural areas. Family farms are acknowledged to have strong social capital [

37] and contribute to the retention of services in rural areas [

3,

4]. Family farmers’ tacit knowledge and traditional farming practices are also recognised as potentially protective to natural habitats, thus enhancing environmental sustainability [

38,

39]. The cultural significance of intergenerational traditional primary producers is also increasingly recognised in culture economy approaches to sustainable rural development [

40,

41]. Overall, as agricultural sustainability debates evolve, the societal relevance of family farming is becoming accentuated and the social, cultural and economic resources and development potentials of family farming are increasingly emphasised. As discussed at length in the sociological literature, the value placed by inter-generational family farmers on socio-cultural capital and not just economic capital is a contributing factor to the sustainability of family farming longitudinally, despite often poor economic viability [

42,

43,

44,

45].

The concept of resilience is used to explain the tenacity of family farms [

43,

44]. Global agricultural commodity markets can experience price shocks due to major weather events or disease outbreaks for example. Resilience is defined as the ability to “withstand, recover from, and reorganise in response to crises: function is maintained but system structure may not be” [

46] (p. 35). Resilience can manifest in three main ways: persistence, adaptability or transformability [

47,

48]. Unlike viability and sustainability, resilience can only truly be tested in times of adversity or crisis, which, according to [

48] (p. 7), can often be viewed as ‘windows of opportunity’. It is at this point that new actions, resources or structures can be mobilised, often drawing from the social domain of the farm family. Family farm decision-making is influenced not solely by profit maximisation but also by social and cultural capital [

42], which enhances resilience [

43,

44,

45,

49,

50]. Another characteristic of resilience in family farming is co-operation [

47,

51,

52,

53,

54] and the co-operative model is a firmly established institution in agriculture worldwide. Drawing on the integrated concepts of viability, sustainability and resilience as presented in

Table 1, particular types of co-operatives are identified as having the capacity to achieve such goals in a harmonised manner.

Co-Operatives in VBSCs

The co-operative is an institution that is firmly established in agriculture, adapting to changing economic, social and political conditions over time. Traditional agricultural co-operative models in the past focused mainly on acquiring bargaining power and scale, generally within supply chain settings [

55]. Authors [

56] (p. 39) state that “many of these traditional co-operatives are rooted in the first half of the twentieth century when words like ‘ecology’ and ‘sustainability’ were barely in the language”. However, consumers are increasingly concerned with where and how their food is produced, evoked by terms such as the ‘ethical consumer’ [

13,

57,

58,

59]. In food markets, there has been a turn to quality, which has supported the emergence of specialised food markets providing differentiated quality produce with special characteristics [

60,

61,

62].

Such markets are claimed to deliver particular types of benefits to producers. It is increasingly accepted within the supply chain literature that producing commodities can expose farmers to global market volatility, threatening their survival [

6,

22,

63]. Differentiation of farm produce by quality rather than competing on price is increasingly recognised as a strategy to buffer against market volatility and achieve competitive advantage in the marketplace [

2,

6,

64]. While co-operatives are a long-standing business model in the agricultural sector [

10], contemporary farmer co-operatives are increasingly embedding themselves in strategic partnership arrangements to access speciality markets. One strategy to achieve this is through the creation of a VBSC [

9]. VBSCs deal with such specialised produce while creating partnership arrangements with entities, such as processors and retailers, to secure market access. VBSCs are characterised by high levels of trust and performance while having shared visions and committing to the welfare of all partners in the chain [

9].

Processes of mobilising external resources outside of the farm unit through collective action have been termed ‘relational flexibility’ [

65] (p. 52). Authors [

66] (p. 13) highlight the notion of ‘reflexive resilience’ as “both the act of looking and the act of being able to change”. Co-operatives and VBSCs are consistent with the concept of relational flexibility because they are defined by co-operation, integration and relationships of partners in the chain.

The literature discusses how the co-operative structure emerged historically to promote and safeguard the less powerful members of society by creating bargaining power and a platform for members to access markets, while reducing transaction costs and improving member incomes [

51,

67]. Co-operatives are often portrayed as ‘fair trade’ business models, which combine social and economic goals of the membership, and focus on collective rather than individual ownership [

68,

69]. Authors [

70] consider the co-operative as a ‘true hybrid’ as it can tailor to market demands while fitting into the hierarchy and arrangements of the market place. Additionally, the co-operative business model creates an environment conducive to innovation, and while this can be largely linked to technological developments, it can manifest in forms such as greater specialisation, adaptation and adding value to produce [

64,

71,

72].

Changes in consumer demand and a growing global competitive market place have forced some businesses, including agricultural co-operatives, to take a more market oriented approach to ensure future sustainability [

73]. In fact, some authors believe that the co-operative model is, potentially, an ideal model for targeting higher value added markets, as it progresses the ideals of the market place while simultaneously catering to producers’ needs and values [

12,

74]. In values-based markets, consumers are considered one of the most valuable sources of information; hence, a marketing strategy that puts consumers first gives firms competitive advantage [

1,

22,

75,

76]. Branding has become a common feature associated with premium markets and is commonly used as a resilience strategy to buffer producers from the volatility associated with commodity supply. Competitive advantage is derived primarily from particular quality-enhancing attributes of products that are difficult to imitate [

77,

78]. Author [

79] argues that some agribusinesses have been slow to develop brands and instead tend to focus on improved efficiency, reducing buyer power through collective supply and creating marketing arrangements in the commodity markets. Among many businesses, including co-operatives, there is a belated recognition of the need to invest in brands and break away from the commodity cycle [

73,

78]. The co-operative model, in this instance, is acknowledged as one that could ‘break the commodity price cycle’ and develop innovative branded products [

78] and is a strategy on which the AotM paradigm specifically relies.

This paper presents a case study analysis of how farm families’ membership of a beef co-operative integrated to a VBSC impacted on their viability, sustainability and resilience. The co-operative is farmer owned and consists of members who produce a premium ‘natural beef’ product. For this co-operative, this means that the cattle going through the co-operative have been raised ‘naturally’. They are pasture reared, without the use of antibiotics or growth hormones and finished on a vegetarian diet. Values espoused by the co-operative are that ranchers must adhere to principles of land stewardship, animal welfare and environmental management. The natural beef products are aimed at specialist buyers of premium produce and consumers who are health conscious and tend to have higher disposable incomes. Meat cuts include briskets, flat irons, sirloin, rib eye steaks; tenderloin and prime rib roasts. The co-operative’s brand differentiates its products in the market-place on the basis of ‘natural’, ‘hormone and antibiotic-free’, ‘naturally raised’, ‘no artificial ingredients’ and high ‘animal welfare’ attributes. These attributes are verified by certification standards and close integration of VBSC partners enhance verifiability. The partners in the VBSC are claimed to share similar values and adopt a business ethic of “Shin Rai”, which is a Japanese term that translates in English to ‘mutual support and mutual reward’. By subscribing to these ideals, the intention is that each segment in the chain reaps the benefits of, and stability associated with, producing a value laden high-value product. While the VBSC model is advocated as having the potential to impact positively on farm-level viability, sustainability and resilience [

5], little work on how this actually transpires in practice has been carried out to date.

4. Findings and Discussion

This section introduces the case study co-operative and then presents findings on the co-operative members’ experiences of operating within a VBSC and impacts arising on farm-level viability, sustainability and resilience.

4.1. The Beef Co-Operative

The beef co-operative was established in 1986 in the Western United States when beef markets were in a state of flux. The majority of ranches, at this time, were highly leveraged financially and under threat due to the falling prices in the commodity markets. This situation of adversity presented itself as a ‘window of opportunity’ to a small number of ranchers who recognised potential to market their beef as unique and target premium markets for better prices. To create their brand, they differentiated their beef product based on a few main attributes: a co-operative of ‘local’ (initially one state) ranch families; producing rancher-owned ‘birth to box’ ‘natural’ beef, i.e., naturally raised on pasture with no antibiotics, hormones or artificial ingredients. The co-operative started with just 14 ranch families located within a particular region who developed their (rancher owned) brand together.

Structurally, the co-operative was set up as a ‘brickless’ organisation, owning no assets. The ‘buy in’ (the acquisition of a share in the co-operative) for members is not monetary; rather it is based on the number of cattle committed to the co-operative. This co-operative operates a pull system of production; forward contracts or agreements for cattle numbers are decided 18 months in advance and prices are then set. Geographical ranch sizes of co-operative members can vary from three thousand acres to the very upper end of the scale towards one million acres. Herd sizes or animal numbers per ranch range from 100 head to 10,000 head of mother cows. The average size is approximately 500 head of mother cows, with the majority of ranches supplying between 300 and 1000 head. Ranch families’ commitments to the co-operative include committing an agreed number of cattle in advance; attending the Annual General Meeting (AGM); and carrying out an annual in-store demonstration to connect with consumers. Members are also required to carry out animal welfare audits and complete legal documentation to guarantee compliance with antibiotic-free and hormone-free standards. As illustrated in

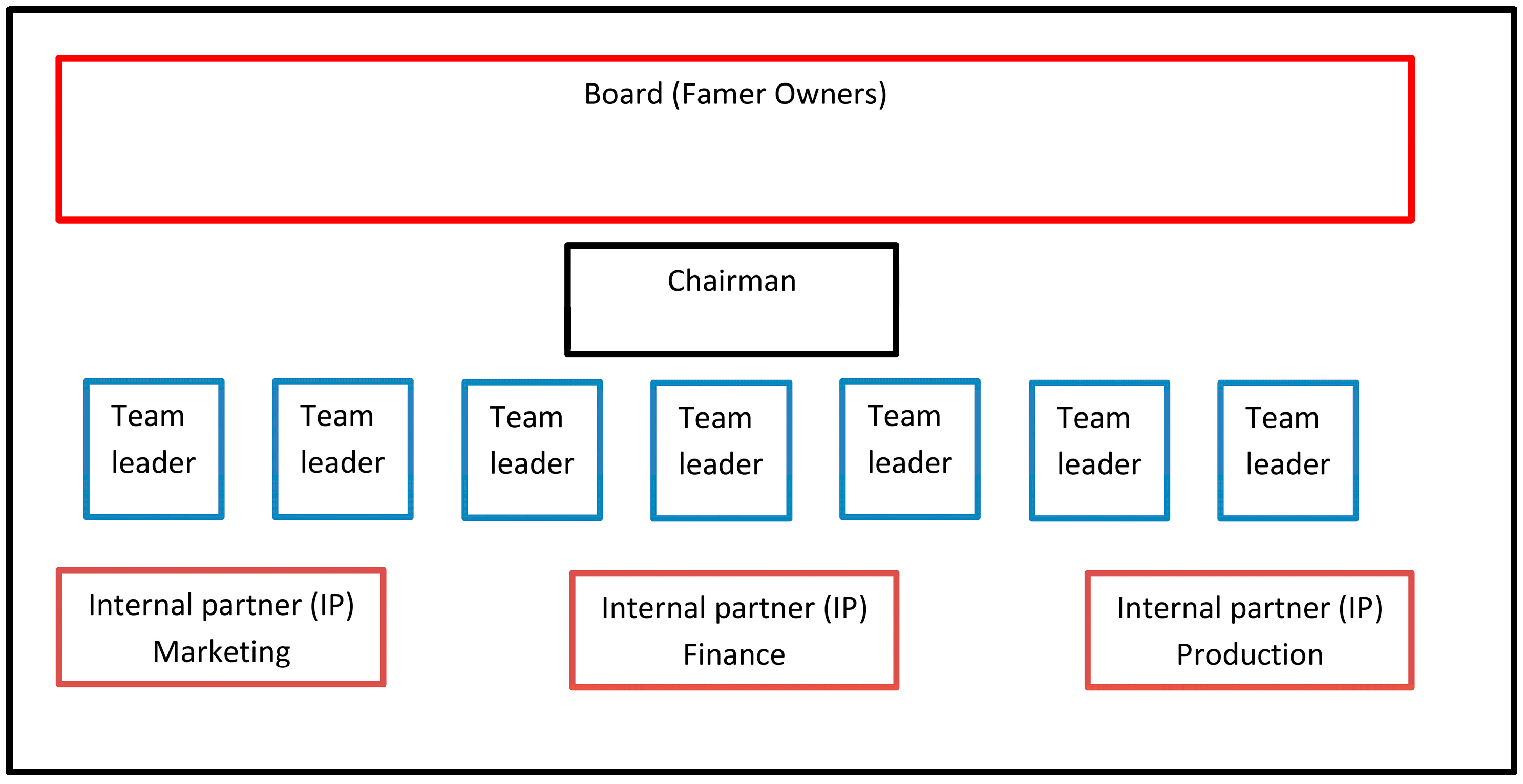

Figure 1, ranch families make up the board of directors and exercise one vote each on major decisions. Decisions are made by consensus, whereby everyone discusses the motion until they reach a decision that is accepted. Additionally, the co-operative has internal partners (IPs) who are members of the co-operative and oversee the running of the co-operative on a daily basis in areas of finance, marketing and production. The IPs are contracted and paid on a per head (of cattle going through the co-operative) basis and are allowed to spend up to 4% of sales to run the company in these specific areas of finance, marketing and production. A smaller board of team leaders (7) are then elected by the membership to monitor the IPs.

The co-operative began on a small scale, directly supplying 1–5 head of cattle per week to an independent retailer. From there, the co-operative attracted a large international customer and grew to supplying 50 head a week. This increased demand allowed the co-operative, due to its increased scale and supply, to access large processing facilities. This main processor has remained a chain partner for over 20 years. The processor is guaranteed a supply of cattle almost 18 months in advance, which offers stability and lower risk. When the co-operative’s international contract ceased due to recession within the customer’s national economy in the early 1990s, the co-operative had progressed within the domestic market, mainly through independent retailers. This diversification of buyers buffered against negative impacts of the cessation of the international contract. Currently, the co-operative only supplies the national market and does not sell internationally. The agreement with the processor remained that co-operative cattle are processed based on a separation programme whereby only the cattle of the co-operative are slaughtered together and these are never mixed with any other cattle. The processor also takes care of the fabrication, grading, boxing and distribution of the beef, which is sold as either boxed beef of specific cuts with the brand or the whole carcass. All of the beef sold, in whatever cut or format, is sold as premium natural beef. As the demand for natural beef grew more generally, so did the membership and customer base of the co-operative. Ten years after the co-operative’s initial establishment, one major US retailer came on board as a customer. As the retailer’s chain of stores expanded, so did the geographical reach of the co-operative’s product. With increased demand for the co-operative’s natural beef product, production now occurs under the co-operative’s brand on ranches spanning across ten states. The co-operative has since rebranded to accurately present its multi-state membership, clarifying that it no longer produces beef associated with one particular state. With the objective of improving and maintaining product consistency, the co-operative chose to add a feedlot stage, finishing cattle on a non-Genetically Modified Organism (GMO) ration/feed three times a day, for a minimum period of 90 days. In the feedlot, they are segregated into their individual pens and are tagged electronically to record information in relation to feed, health and conversion rates.

Figure 2 illustrates the partners involved in the case study VBSC.

Over time, the co-operative added different product attributes. While ‘natural beef’ remains the main product category, the adoption of third party animal-welfare auditing and additions such as ‘grazewell principles’, extend the range of premium product attributes. ‘Grazewell principles’ advocated by the co-operative, underpin ranchers’ commitment to the management of animal health, environmental standards and land stewardship. For example, pasture management is undertaken in a way that is not in any way detrimental to biodiversity or harmful to natural plant species. Thus, management decisions are taken with a long-term vision to be economically, ecologically and socially sound. Also, a ‘grass finished’ product was later developed, which is differentiated from the ‘natural’ beef product through finishing cattle on grass pivots at the feedlot rather than being confined in the lot.

The co-operative, at its peak, had approximately 120 ranch family members in 2010. However, at the time of our study, numbers had declined to approximately 60 ranch families. Based on interviews conducted with members of the co-operative, two main factors contributed to this decline: firstly, members were at times able to secure higher prices for their cattle on the commodity markets; secondly, the mandatory adoption of third party audited animal welfare standards sparked political feelings among some members and made compliance more onerous at farm-level. The decrease in member numbers has placed increased pressure on the co-operative to keep up with the demand for its beef and, therefore, the decision was taken by the co-operative to buy cattle outside of the co-operative to maintain supply.

Despite the related challenges of retaining members and meeting demand for their produce, the co-operative is successful financially in terms of securing incomes and gaining market access. Interviews conducted with farmer members allowed insights to how the viability, sustainability and resilience of members was impacted by membership of the co-operative.

4.2. Viability

4.2.1. Market Orientation

The co-operative was formed in 1986 when commodity prices were at an all-time low and the financial viability of many beef ranches was under threat. In addressing such a challenge, these ranchers moved to producing a value-added product aimed at premium markets and leveraging strategic partnerships to gain market access. The integration of this case study co-operative to a VBSC, which involved creating alliances with partners in the chain such as processors and retailers, facilitated it to access premium markets. Targeting premium markets through appropriate branding and accessing premium markets through a VBSC has allowed co-operative members to experience stable pricing and avoid much of the volatility experienced within the commodity markets:

“And so the [names of retailers] … it’s a value-based marketing merchandising … they’re selling to people who have strong environmentalist beliefs. And they’re the people who also are willing to spend the money to say we support and we endorse what we’re doing, what you’re doing on producing your beef that way.”

Generally, the product of the co-operative commands an average price premium or a mark-up of between 30% and 31%. Most of the members identified this strategy as one of the main reasons they have experienced enhanced viability and remained sustainable. One respondent noted:

“It’s important to have those sustainable prices, and what I tell people is I don’t mind missing those high peaks in prices, but I gotta stay out of the valleys. And with a high fixed cost, a real drastic cost reduction would just really strain our ranch and its ability to continue. Thankfully, the prices have been high enough for the last few years we are relatively debt free, we have cash in the bank we have a feeling of stability that we’ve never had in the history of this ranch.”

4.2.2. Pricing Structure

Prices are set using a ‘cost of production model’ focusing on all the costs to members of producing a pound (in weight) of beef at farm-level. Input costs such as feed, veterinary costs and depreciation of machinery are inputted to the cost of production model, and prices are set to cover these costs and include a minimum 4% profit margin. These figures are then used to generate the average cost, across the board, to produce a pound of beef. The price is then set in such a way that 75% of the membership is profitable in a given year, due to variability in costs of production. This variability in costs of production can usually be attributed to contextual differences at farm-level including environmental factors such as soil and climate, as well as differing levels of managerial capabilities leading to higher costs of production for some members. Members who have higher costs of production and fall outside of the ‘profitable’ 75% are encouraged to work at improving efficiency of production at farm-level, thus incentivising them to become more profitable. Following these principles, prices and volumes of product are identified 18 months in advance and proposed to partners in the chain at the co-operative’s AGM. Other agreements, relating to the number of cattle each member commits, target weights, and the different times of year that different members send their cattle to the feedlot, are all reached at the AGM. Meat prices are then ‘set’ based on farm-level costs of production, processing, packaging, distribution. Distribution of costs and profits across the chain is also considered in the price-setting process.

“If it’s cost of production and you’re selling to the commodities it really doesn’t matter if you know or not, you’re gonna make money or not depending on what the commodity does. But in our case you know your cost of production and you put the price on it.”

In setting prices, the members make the transition from ‘price takers’ to ‘price makers’. Respondents spoke about how this minimises risk and gives them security to plan for the future. One respondent stated:

“We know what our cost of production is and we know what our cattle are going to sell for, and so from a budgeting standpoint, we really have that pretty well locked in 18 months in advance.”

No assets are held by the co-operative. All equipment and office space are rented and all costs are recovered from the sale of meat. The administrative and bureaucratic procedures of the co-operative, including employee wages, are funded by taking a percentage from the sale of meat to operate its daily business. The co-operative operates on a ‘return to ranch’ policy whereby all ranchers’ profits are returned to the ranch at the end of the year and no surplus is retained by the co-operative.

4.2.3. Payment Structure

The payment structure operates on the basis that the members receive a maximum of four payments each year rather than receiving one lump sum when the cattle are slaughtered. The ranchers own their cattle right up to the stage that they are slaughtered. Once the cattle reach 15 months, and/or have reached target weights, they are sent to the feedlot for an average of ninety days. It is at that point that ranchers receive their first payment, which takes the form of a placement bonus that varies according to the time of year that cattle are placed. The variance between prices at different times of the year was outlined by the finance IP:

“You get your cattle to the feedlot the right time on the agreed months so we have them to finish. Then we start a placement bonus. It varies by month because sometimes it’s harder to get cattle and so it varies from a high of $100 in December, November and January are $70 and then July, August, September are the easiest months to get cattle and they are 30 bucks.”

The second payment is paid directly by the processing plant to members when slaughter occurs. The third payment is conditional on hitting ‘bull’s-eyes’ or target specifications, in terms of fat and rib eye carcass quality, among other specifications. The last payment of the year is based on the patronage dividend, which in turn is based on the number of head of cattle they have placed through the co-operative that year.

In these various ways, membership of the co-operative enhanced members’ viability not least because of their transition from price takers to price makers. They are now in a strategic position to cover their costs and incorporate a profit margin. Additionally, placement bonuses, hitting ‘bull’s-eye’ and target specifications incentivise and allow members to be rewarded financially for producing a consistently high quality product for the co-operative’s brand. Lastly, the dividend at the end of the year predictably paid out due to their membership of the co-operative enhances their financial stability.

There is no doubt that the co-operative being integrated to a VBSC enhanced the viability of its members. However, there are certain trade-offs involved in being a member of the co-operative, such as the need for cattle to be finished in a feedlot. Many respondents felt that the feedlot stage introduces an element of risk which is borne by them, although they themselves are not in a position to control conditions and circumstances once their cattle leave the ranch. Many respondents referred to a ‘loss of control’, having to rely on feedlot staff to care for their animals, make target weights in a timely manner and market them at the right time.

“We have to rely on the feedlot to market the animals at the right time, make sure they’re harvested at the right time. And if they’re short meat they may push a bunch through earlier, so that we’re not hitting the target and bull’s-eye stacks that would be another loss of control.”

The merging of different herds in the feedlot often led to illness or possible death of animals, with one member stating:

“We’ve had groups of cattle get sick and financially it hurt big-time … if you couldn’t get around that or get that fixed, it would put us out of business...there’s been several ranches that have had health problems and have had to drop out. That’s the tough part; you own the cattle ‘til the head drops … I think that was probably the worst, most negative thing for us was not being able to control the sickness in our cattle, because they were happy and healthy when they left here, and obviously we’re not the only ranchers that have that.”

Regarding market orientation, many respondents noted that there are pressures to remain progressive when supplying premium markets. The meat products of the co-operative claim attributes of naturally raised, with no hormones, antibiotics or artificial ingredients. They are now also subject to undergoing third party certifications. The majority of members interviewed perceived the adoption of certifications and how they were proposed to members as problematic. They referred more to pressures to adopt practices demanded by their largest customer. Certification in particular was considered by some members as an ultimatum rather than a choice, as to continue supplying their main retailer into the future made the adoption of these standards mandatory.

“Oh I think if we’re going to sell to [name of company] which we have to … we’re going to do whatever they want. And … the certifications, they’re not cheap. There’s the dollar cost of it, plus the time that it takes.”

And:

“When that lady … from [name of retailer] came and talked to us about the standards and how it was going to come down, that was the first time I came away from a meeting with a sick feeling in my stomach.”

The reliance on this main consumer raises questions in relation to the long-term sustainability of the co-operative. If their biggest customer abandoned them, then how viable would the co-operative and its members be? Questions were also raised in relation to the long-term effects of adopting new product attributes. Will ranchers be able to recoup their costs through higher prices and in doing so, are consumers going to be willing to pay more? It is clear that the stable pricing provided by the chain contributes to viability at farm-level. However, despite solutions such as the Out of Programme (OP) insurance (

Section 4.4.2), there are certain trade-offs, such as the risks associated with using the feedlot and costs incurred in the adoption of standards and certification processes, which these ranchers generally would not need to comply with if they were outside the co-operative.

4.3. Sustainability

Focusing on the different facets of sustainability, the data indicated that the VBSC co-operative delivered a number of positive sustainability impacts at farm-level.

4.3.1. Economic Sustainability

The economic sustainability or the viability of members, as mentioned above in

Section 4.2, and the co-operative has been enhanced through market orientation and profitability. Market profitability was enhanced due to the co-operative’s pricing structure and the ‘pull’ system of production (based on forward agreements made 18 months in advance). Prices, volumes of product and target weights are set 18 months in advance. This is in contrast to the conventional (push) system, where producers produce as much output as they wish to sell in markets where prices can fluctuate according to global market circumstances.

4.3.2. Environmental Sustainability

While the environmental indicators are harder to measure without hard quantitative data, the ‘natural’ label of this co-operative means that cattle are naturally raised with no antibiotics or hormones. In line with the ‘grazewell principles’ of the co-operative, land is managed in an ecologically and environmentally friendly way, for example no artificial fertiliser is applied and, depending on farm circumstances, minimal, if any, housing during winter. Natural holistic remedies are used for animal health and use of antibiotics is a last resort. If this happens, these cattle are labelled as OP cattle and are sent to the commodity market instead. Also at the feedlot stage, a certified non-GMO feed is used. Many of the ranchers have created natural systems to deal with constraints, such as water shortages during the summer months by building their own reservoir systems to hold water supply after the annual snow melt. A primary concern of the ranchers is farming in a sustainable manner that is sensitive to the ecological integrity of the land. Additionally, much of the on-farm ranching is carried out in a traditional ‘ranching by horseback’ style, requiring minimal use of mechanisation. One rancher commented as follows:

“We want to invest it in things that will improve the long-term productivity of this ranch so we don’t buy new pick-ups we don’t buy new tractors but we do like to invest in fencing, we do like to invest in water developments and in education.”

Overall, the co-operative’s brand differentiates itself in the market-place on the basis of natural, naturally raised, hormone- and antibiotic-free, and high animal welfare attributes. Therefore, there is a clear relationship between the brand and aspects of environmental sustainability.

4.3.3. Social and Innovation

Focusing on the social and innovation aspects of sustainability, themes of education and innovation emerged strongly in the data. It emerged that members attached a high value to the social aspect of the co-operative and to their own tacit farming knowledge. Some of the ranchers interviewed identified education as one of the most valued benefits of being a member of the VBSC co-operative. The co-operative runs educational seminars and routinely seeks out external professionals to bring expertise to members. All ranchers assigned a great significance to this:

“The educational aspects, cattle handling too, have been a real plus. I think it makes us better ranchers, because we’ve learned a lot about how to a handle animals and keep m safe … there is just a lot of opportunities to learn things. And we got to work with … a professor from [name of university] … she … taught us how to get down and actually think about what an animal is seeing … and in this country about 70% of cattle go through something that she has designed or she has had an influence on design of … and when we put in new corrals in the last 3–4 years we have used a lot of her principles, used a lot of angles and stuff on the gates, on the corrals and stuff, worked out well.”

It was evident that interviewees were seeking out ways to improve their farms and the co-operative was a means of achieving this. Innovative approaches were adopted regularly, stemming from either professional advice and/or sharing of knowledge between ranchers. Many interviewees commented on the value of learning from other members of the co-operative and a culture of willingness to share knowledge within the group:

“That camaraderie and the value of everybody’s knowledge and no two ranches are the same... We’re all likeminded people, but each individual ranch is different and operates differently. So you pick things out that you can use and things that you don’t want to use, but it’s set up the way that we try to help each other.”

There was a clear interdependence of members and a sense of embracing change and innovation as a sense of duty, not just at the individual farm-level but also at the level of the co-operative:

“We don’t want to be the worst ones in the group, you know, we have some pride so we want to be competitive and not be a burden to anybody. So you make changes as fast as you can—that’s part of survival too, and sustainability is to keep up with technology.”

Learning and innovation also arose from interactions with other partners in the VBSC. At a technical level, the availability and use of carcass data were mentioned as important benefits of co-operative membership. Due to their close collaboration with the meat processing facility, carcass data is available on each animal, which is not available to ranchers outside the co-operative:

“We get good data back on every animal that we place … So we’re getting … actual carcass data that I can tie through back to the cow that had that calf. So that just allows me … to cull out the ones that aren’t performing for me. And we’ve made a lot of progress with that and you know we can’t get that information otherwise.”

Succession was highlighted as a further benefit to increasing members’ sustainability. This hinged heavily on creating a viable enterprise to which family members were attracted to as a lifestyle and career option.

“I guess [name of co-operative] has allowed our kids to come home and they both have their interests, and when they came home they were able to purchase cattle, and so they have their own cattle that run with the ranch cattle.”

Furthermore, a culture of co-operation is instilled in some of the younger family members of the co-operative by parents and even grandparents. Succession not only has an impact on the intergenerational transfer of land, but also on the membership base within the co-operative:

“And these guys are the third generation, because [name] folks started it with us, we didn’t have kids when we started it, so our kids truly were raised with [name of co-operative].”

While being a member of the co-operative has had a profound impact on members at farm-level, it was clear that this was a ‘two way street’. The ranchers rely on the co-operative to enhance their sustainability, while the co-operative relies on the membership for sustainability. The sustainability and viability of any co-operative relies primarily on membership for investment, governance and supply purposes. In recent years, membership loss has been a significant issue for a number of reasons.

While integration into a VBSC has allowed the co-operative to avoid the volatility of the commodity market, it is not completely immune to prices effects when it comes to the membership. On numerous occasions, it emerged that when the generic market prices were high, the co-operative suffered membership loss. This creates problems when the co-operative is in a system of committing cattle numbers to consumers 18 months in advance:

“These high prices the last few years have been a real stress on the co-operative, because you could get as much, if not more money by just selling your cattle on the generic market … no meetings to go to, no in-store demos to do, no sitting in a circle and telling others how you feel about being here today … you could just stay at home and do the things you want to do and get better money than you’ve ever gotten in the history of your ranch. And not only that … you don’t have to keep your cattle through the feedlot finishing phase.”

Likewise, the addition of attributes appeared to cause major losses in membership:

“Every time we’ve added an attribute, then we’ve lost members.”

As a co-operative, this has put pressure on the overall sustainability of the operation. In particular, one customer has put a lot of pressure on the co-operative to progress and keep up with market requirements:

“[Name of company] is such a huge part of it, it pretty much dictates a lot of the direction we go and we’re just trying to catch up and meet what their requirements are to deal with the public. They like to make promises that are hard for us to keep, keeping the public happy with what’s in the case. More time consuming doing the extra things that you wouldn’t have done before.”

However, as this is their biggest customer (purchasing over 60% of their output), if they were not to adhere to their requirements, what impact would this have on the future of the co-operative and its long-term sustainability? This has sparked political feelings among the membership about how these proposals ‘came down’ as opposed to the self-governing element that the co-operative model transposes. This highlights that these types of co-operatives are by no means immune to industry demands; in fact, they are even more exposed in many respects. Remaining sustainable in premium markets means continually re-assessing and progressing the product. However, this all hinges on the cost at farm-level and whether consumers are willing to pay for additional attributes. Even wider consideration depends on the economy and the availability of disposable income for consumers.

4.4. Resilience

4.4.1. Co-Operation and Differentiation

Resilience is defined as the ability of a system to respond to threats, generally using techniques of adaptation, transformation and persistence [

43,

47,

48]. Co-operation and product differentiation are examples of resilience strategies:

“Our own ranch had purchased additional land and we found ourselves deeply in debt and we were basically on the verge of going broke and a lot of people in the industry were. It was a bad time in the industry, banks were calling in loans … it was about that time that [name] … over at [name of place] had the idea that maybe we could get together and find a way to make our beef unique, so that we could get out of the commodity beef production and start producing cattle that would get a little bit of a premium. And the goal was not to get rich, the goal was not to develop a super-premium thing it was just … we were just desperately trying to find a way to stay in business.”

Case study evidence revealed how various other strategies of resilience were employed by co-operative members, such as leveraging relational reflexivity and drawing from extended resources made available through co-operation. The integration of this co-operative to a VBSC allows them to access the resources of their partners. Partners made investments in the co-operative by offering financial and technical assistance, assisting with vaccination and nutrition protocols, among others. These resources are largely tied to the nature and longevity of the relationships between partners of the chain, but are also fundamental to the stability and resilience of the co-operative, as explained by the feedlot partner:

“[That]—goes back to a group of ranchers being able to partner with bigger players that have all the infrastructure. I mean we have millions of dollars invested into the infrastructure that [name of organisation] uses. And the processor has millions of dollars invested into the infrastructure that [name of co-operative] uses … and … because we do it on a much larger scale … [name of organisation] and other users are able to utilise resources that we have that they couldn’t otherwise ever get.”

Financial arrangements also allow rancher members some flexibility on feed payments and advance payment options at the feedlot stage, to help generate cash flow:

“Some people will take a forward payment on their cattle too, so [name of entity] will give them forty per cent or so of what those cattle are bringing, so they have something to operate. And then when they … kill … they pull it out [and] they get it back.”

In times of crisis, for instance during wild fire season, some chain partners have been known to subsidise the co-operative, with one rancher stating:

“[Name of retailer] last year actually subsidised us and one entity, supposedly they spend next to a million bucks which probably isn’t very much to [name of entity], but anyway. It was a gesture in the right direction for sure.”

As mentioned earlier, membership loss in recent years has had a negative impact on the supply of cattle. The volume of cattle produced is generally agreed 18 months in advance. However, when prices rose on the commodity market, some of the less committed members withdrew their cattle from the co-operative. This had repercussions for the whole chain, compromising the reputation of the co-operative as a reliable supplier and leaving retailers without sufficient volume of product. With no system or rule in place in the co-operative to deal with such occurrences, they had to create another solution. In response to shortfalls in supply, partners in the chain (the feedlot, the processor and the co-operative) have come together to form a separate entity to purchase cattle outside the co-operative. This activity is funded by the co-operative (50%) the feedlot (25%) and the processor (25%). Profits from the sale of ‘purchased cattle’ are distributed in the same proportions. In this way, the co-operative addressed the threats to brand reputation and the stability of the VBSC overall:

“All of a sudden our demand kept growing and we were losing members. So then we started having to buy cattle that met [name of certification] qualifications … and that was a challenge, I mean we weren’t set up to do it.”

Some members believed that purchasing cattle gave them greater flexibility rather than adding new members to the co-operative whose systems might not necessarily suit the co-operative in the long-term. Therefore, the purchasing of cattle from non-members could be perceived by members as a resilience strategy. However, in order to maintain the co-operative in the long-term, adding new members is necessary for generational renewal. For this, the attractiveness of the co-operative as an institution that promotes farm-level viability, sustainability and resilience must be maintained.

4.4.2. Self-Solution of Problems

The issue of illness at the feedlot stage was highlighted as problematic, due to the merging of herds and ensuing animal stress and illness. As members own the cattle until ‘the head drops’, this presented a huge financial stress on members. Based on members’ narratives, however, it emerged that the co-operative has come up with a solution in creating an ‘Out of Programme’ or ‘OP’ insurance system, by drawing on member skills:

“We were losing a lot of rancher members because their cattle would go to the feedlot and get sick and they stood the risk … Cattle would need antibiotic treatment and the leadership came up with a proposal that the out of cattle programme that the co-op would simply buy them and re-sell and collectively as a co-op we either make or lose money. Well the proposal came to the annual meeting there were reasons that it wasn’t a good idea and we created what we call OP insurance. If the co-op buys them at market value then it transfers all the risk to the co-op therefore the rancher doesn’t have incentive to do a better job, and if the rancher stands all the risk then the risk for many of ‘em was too great and they were just gonna have to get out. The OP insurance [means] the high risk cattle pay $5 a head into a pool, the low risk cattle, so ranchers that haven’t had problems pay $2 into the pool … and at the end of the year that money is divided out amongst the cattle that get sick, so it gives those ranchers more than they would have received but not everything. So they don’t go broke but there is an incentive to do better. And that simply came from a handful of ranchers working together in a room.”

The co-operative has enhanced the resilience of members and vice versa. The purchasing of cattle, while a controversial issue, is a crucial resilience strategy to maintain the sustainability of the co-operative. In 2015, approximately 60% of the cattle sold through the co-operative were purchased outside the co-operative. These purchased cattle have to meet certain requirements. For example, they are purchased directly from ranches and cannot be third party owned; they must be classified as ‘natural’, using the same criteria as beef produced by co-operative members (supported by legal affidavits); and they are subject to auditing by the same external certifier as the co-operative. Many respondents believed that such a situation represents an abandonment of some of the first principles of the co-operative, which increases risk as a result of diluting the story of their brand:

“Well it was one of the first attributes that they said was to own the cattle from birth to harvest and I know that they have audits and all this on the people that they buy cattle from … but it’s a co-op and the first attribute was that you owned the cattle and this co-op doesn’t do that anymore.”

It is clear that some members feel that this change may not necessarily be reflective of the values they signed up to. Mentions of ‘risk’ with purchased cattle also came through, in that they do not know where these cattle are coming from and adding these to their supply is increasing both the risk of a food scare and financial risks. Moreover, these changes and the disproportionate influence of chain partners raise questions about the long-term direction of the co-operative, with some members mentioning the possibility of it being possibly sold in the future:

“We now purchase a lot of cattle so in its most basic sense [name of organisation] could actually continue to move ahead without the co-operative rancher members.”

Resilience in this instance emphasises the benefit of the strategic partnerships within the VBSC in allowing for mutual benefit and enhanced access to resources for the membership. This has manifested in both technical advice at farm-level, such as the carcass data, allowing the membership to make their operations more efficient, thus profitable; and at the level of the co-op, in adapting strategies such as purchasing cattle and the OP insurance programme to ensure the continuation of the co-operative. However, it is clear that, over the years, this co-operative has become more business-oriented and less-member oriented and this has increased challenges in maintaining member commitment and the stability of the co-operative. In order to deal with such issues of change that have to be made among the membership, there is a need to mobilise meaningful member understanding and participation to ensure continued success.

5. Conclusions

This co-operative has had a profoundly positive impact on rancher members’ viability, sustainability and resilience. This manifested in increased profitability through pricing structures and market orientation; increased sustainability through whole family involvement, education, innovation and self-solution; and resilience through access to greater resources. These positive impacts are enhanced through the integration of the co-operative model to the VBSC.

However, problematic issues emerged such as ‘loss of control’ of cattle and power struggles impacting on membership levels, which have threatened to undermine benefits arising for members and for the co-operative itself. Despite the co-operative’s financial success in providing members with more stable incomes and a route to market, it is clear that some decisions taken by the co-operative have led to disengagement among members. This threatens the long-term sustainability of the co-operative.

Furthermore, the integration of the co-operative to a VBSC, while providing access to markets and resources, has resulted in partners with similar but also differing interests working together. Power differentials and dependencies have arisen in the VBSC, leading to tensions within the co-operative. The mandatory introduction of animal welfare standards and external certification are examples of decisions taken by the co-operative causing dissatisfaction among members. This points to a central weakness of the co-operative, which is its dependence on one main customer and the resultant power of the latter over the decision-making of the co-operative. This poses athreat to the overall sustainability of the co-operative and, ultimately, the VBSC. In this sense, to maintain the co-operative, there is a need for enhanced participation of the membership and further growth of the membership base, as well as balance in decision making and further diversification of customers.

Co-operatives embedded within VBSCs need to be able to balance their own objectives and needs with those of chain partners. As found in the analysis of this paper, however, co-operatives integrated to VBSC structures can be even more exposed to industry demands than traditional supply chains as they are expected to respond to and grow with chain partners. Such relationships with chain partners have compelled our case study co-operative, according to some of its members, to become more business focused and less rancher oriented. Pressures exerted by chain partners on the co-operative to change and adopt certain decisions have made members question the extent of their own influence on the co-operative. This, in turn, has led to a decline in the membership of the co-operative, compromising the stability of the co-operative. Therefore, while co-operatives are adaptable models suitable for integration to VBSCs, which results in potentially positive impacts on farm-level viability, sustainability and resilience, there is a need to caution against dilution of co-operatives’ internal values and objectives. This finding is consistent with [

81], who found that involvement in multi-scale relations can shape and influence outcomes for local food systems.

This particular co-operative approach may have the ability to address some of the problems experienced in other contexts such as the Irish beef sector, where viability is poor but sustainability and resilience attributes are strong. Lessons such as leveraging relationships, forward contracting and utilising relational reflexivity and self-solution provide useful insights for developing beef co-operative approaches in new contexts.