Sustainable Retailing in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

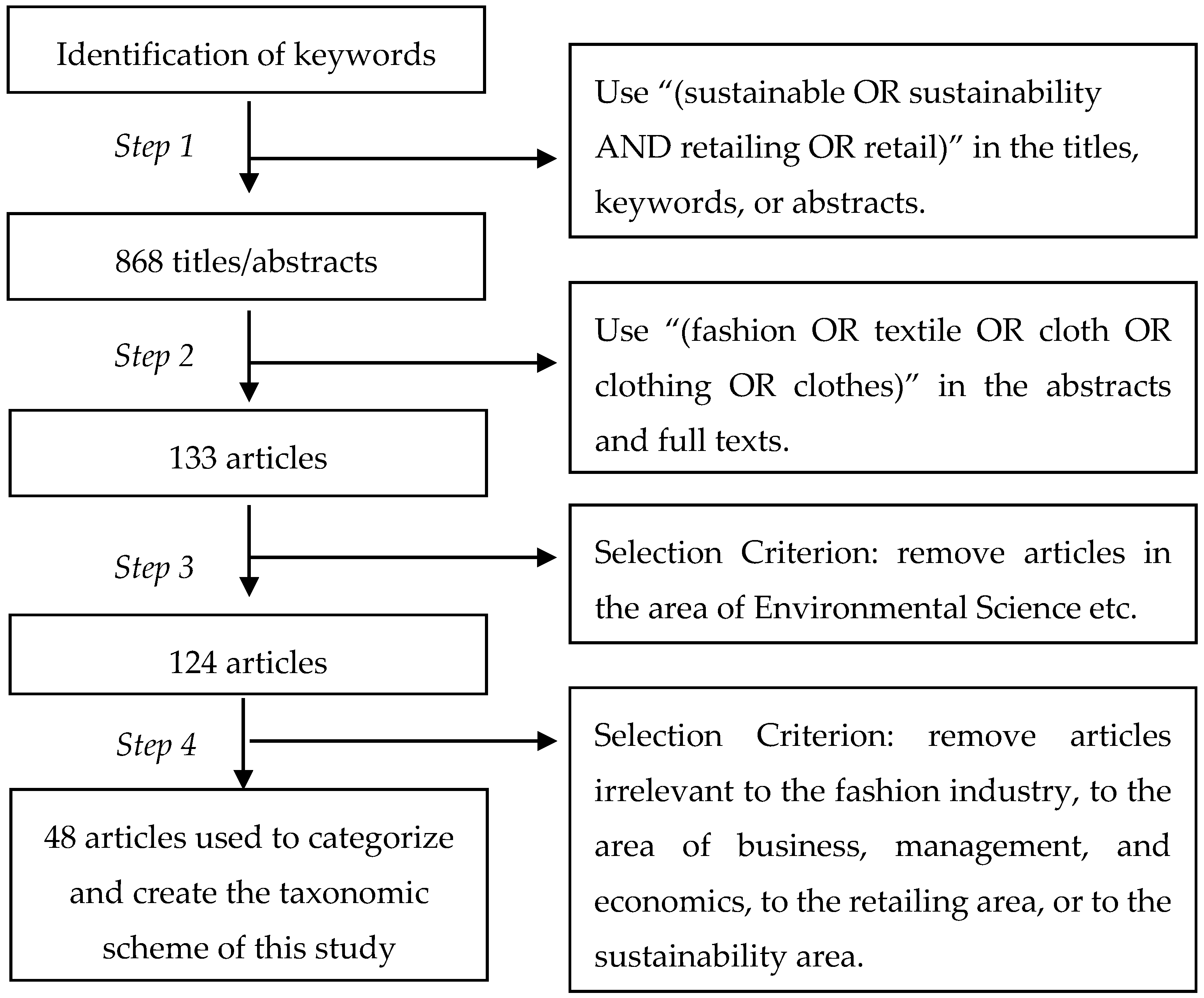

2. Research Methodology

3. Results

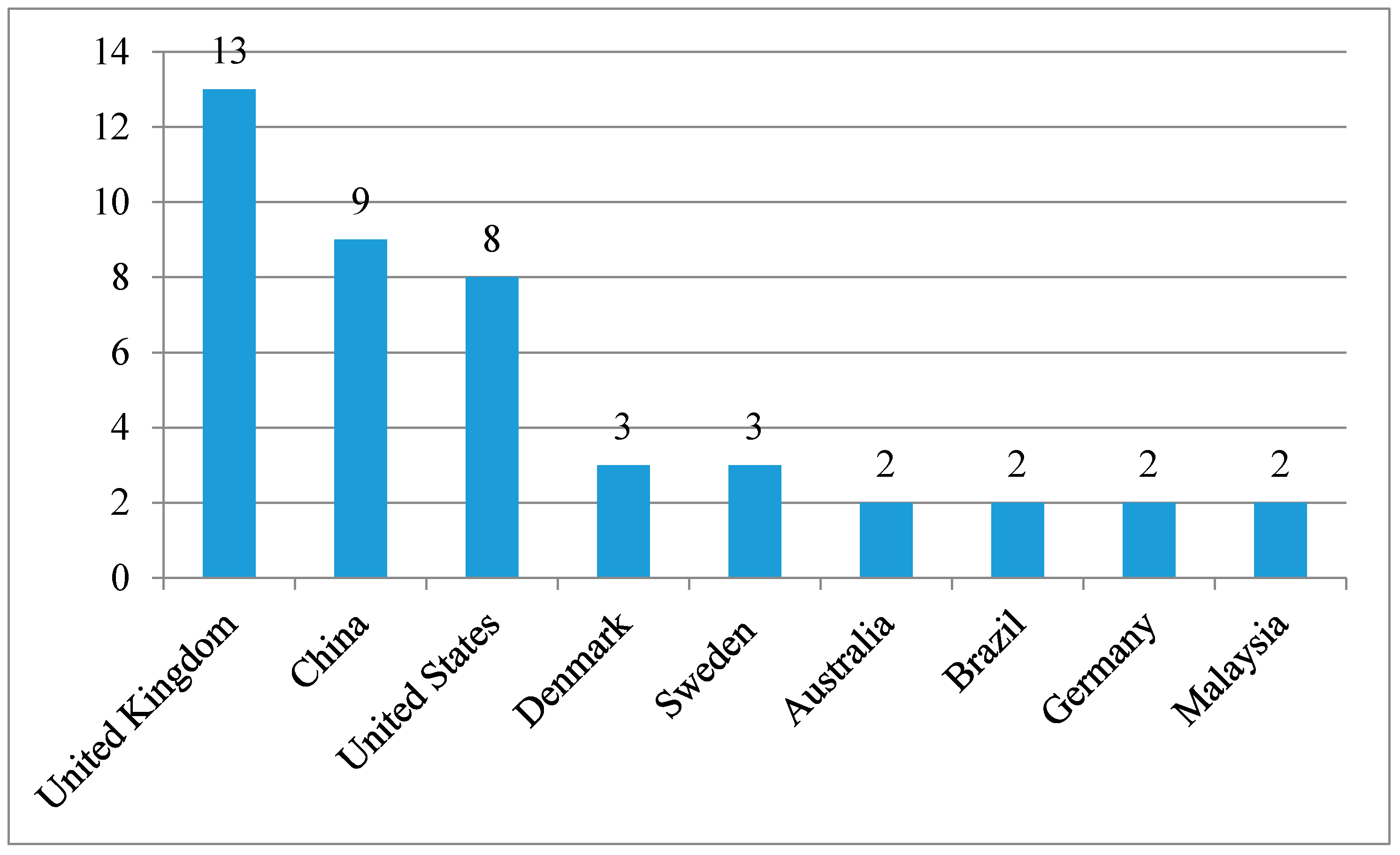

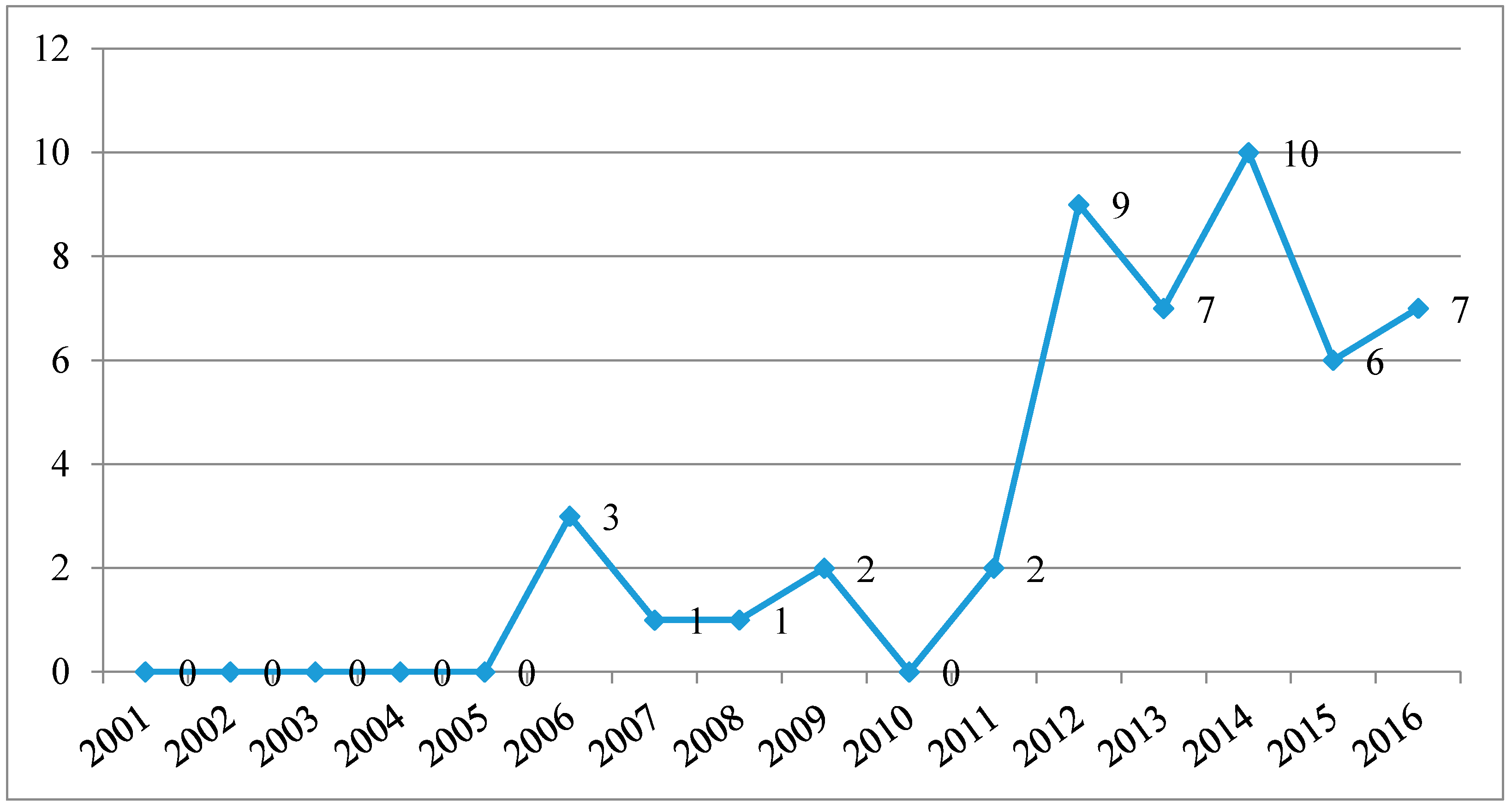

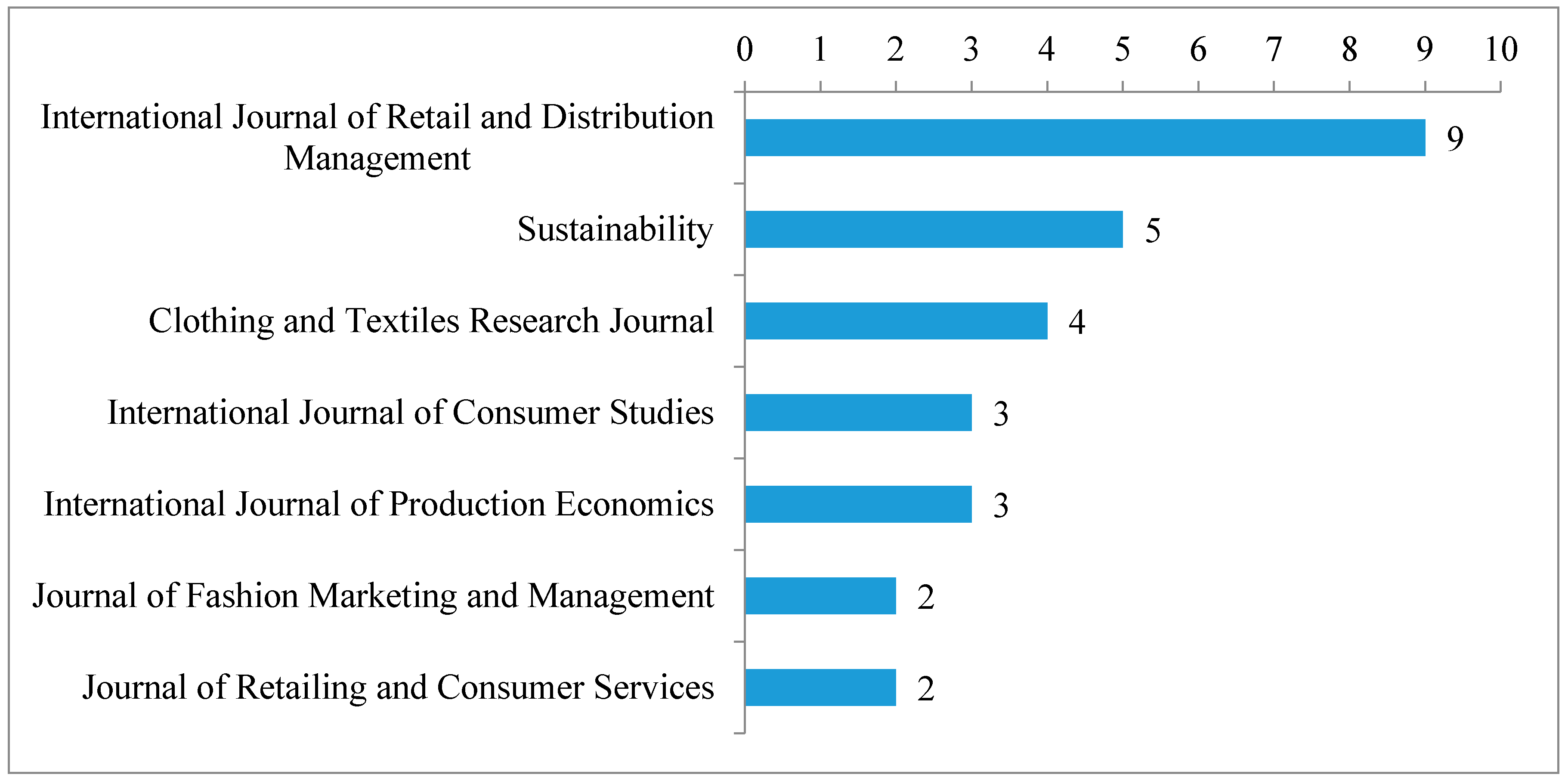

3.1. General Overview of Publications

3.2. Content Analysis

3.2.1. Area 1. Sustainable Retailing in Disposable Fashion, Fast Fashion, and Slow Fashion

3.2.2. Area 2. Green Branding and Eco-Labeling

3.2.3. Area 3. Retailing of Secondhand Fashion

3.2.4. Area 4. Reverse Logistics in Fashion Retailing

3.2.5. Area 5. Emerging Retailing Opportunities in E-commerce

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Institute for Sustainable Development; Deloitte & Touche; the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Business Strategy for Sustainable Development: Leadership and Accountability for the 90s; Diane Publishing Co.: Collingdale, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics and Facts on the Apparel Market in the U.S. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/965/apparel-market-in-the-us/ (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Ytterhus, B.E.; Arnestad, P.; Lothe, S. Environmental initiatives in the retailing sector: An analysis of supply chain pressures and partnerships. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 1999, 6, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F. Food retailers as ecological gatekeepers. An international comparison between Switzerland and Sweden. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Research Conference of the Greening of Industry Network, Heidelberg, Germany, 24–27 November 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Durieu, X. How Europe’s retail sector helps promote sustainable production and consumption. Ind. Environ. 2003, 26, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Erol, I.; Cakar, N.; Erel, D.; Sari, R. Sustainability in the Turkish Retailing Industry. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 17, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Lowson, R.; Peck, H. Creating agile supply chains in the fashion industry. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2004, 32, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, A.K.Y.; Lai, K.H.; Cheng, T.C.E. A multi-research-method approach to studying environmental sustainability in retail operations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Yun, J.C.; Youn, C.; Lee, Y. Does green fashion retailing make consumers more eco-friendly? The influence of green fashion products and campaigns on green consciousness and behavior. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 30, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, T.E.; Miemczyk, J.; Howard, M. A systematic literature review of sustainable purchasing and supply research: Theoretical perspectives and opportunities for IMP-based research. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 61, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosman, H.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Brun, A.; Rosen, M.A. From a systematic literature review to a classification framework: Sustainability integration in fashion operations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhoff-Isakhanyan, G.; Wubben, E.; Omta, S.W.F. Sustainability benefits and challenges of inter-organizational collaboration in Bio-Based business: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2016, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Consumer clothing disposal behaviour: A comparative study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bly, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Reisch, L.A. Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, M.A.; Tu, N.T.; Van Anh, D.; Zagitang, B.; Vegafria, E. Fast fashion quadrangle: An analysis. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2014, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Goworek, H.; Fisher, T.; Cooper, T.; Woodward, S.; Hiller, A. The sustainable clothing market: An evaluation of potential strategies for UK retailers. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 935–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, H.-M. Fast-fashion consumers’ post-purchase behaviours. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pookulangara, S.; Shephard, A. Slow fashion movement: Understanding consumer perceptions—An exploratory study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L. Consumers interpreting sustainability: Moving beyond food to fashion. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 1162–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sustainable fashion supply chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, G.; Ang, K.L. Online fashion retailing and retail geography: The blogshop phenomenon in Singapore. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 2016, 107, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.V.D.; Mascarenhas, A.O.; Tronchin, G.R.; Baptista, R.M. Socially responsible consumption in the fashion retail industry: Analyzing consumer intentions to avoid buying from companies denounced by contemporary slavery. Revista De Gestao Social E Ambiental 2014, 8, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Faust, M.E. Cashmere: A lux-story supply chain told by retailers to build a competitive sustainable advantage. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C. Green materialities: Marketing and the socio-material construction of green products. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2014, 23, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C. Images of responsible consumers: Organizing the marketing of sustainability. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C.; Fredriksson, C. Sustainability service in-store: Service work and the promotion of sustainable consumption. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, H.J. Are fashion-conscious consumers more likely to adopt eco-friendly clothing? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2011, 15, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.E.; Norum, P.S. Willingness to pay for socially responsible products: Case of cotton apparel. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyllegard, K.H.; Ogle, J.P.; Dunbar, B.H. The influence of consumer identity on perceptions of store atmospherics and store patronage at a spectacular and sustainable retail site. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2006, 24, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainable consumption and the UK’s leading retailers. Soc. Responsib. J. 2014, 6, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Greening retail: An Indian experience. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L.; Schröder, M.J. Accessing and affording sustainability: The experience of fashion consumption within young families. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryding, D.; Navrozidou, A.; Carey, R. The impact of eco-fashion strategies on male shoppers perceptions of brand image and loyalty. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2014, 13, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Chen, M.D.; Workroom, W.H. Financial attributes and performance of luxury-goods brand strategies. Taiwan Text. Res. J. 2009, 19, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Beh, L.S.; Ghobadian, A.; He, Q.; Gallear, D.; O’Regan, N. Second-life retailing: A reverse supply chain perspective. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 21, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delai, I.; Takahashi, S. Corporate sustainability in emerging markets: Insights from the practices reported by the Brazilian retailers. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvass, K.K. Post-retail responsibility of garments—A fashion industry perspective. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2014, 18, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.P. The triple bottom line: Undertaking an economic, social, and environmental retail sustainability strategy. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Li, Q. Impacts of returning unsold products in retail outsourcing fashion supply chain: A sustainability analysis. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Choi, T.M.; Lo, K.Y. Enhancing economic sustainability by markdown money supply contracts in the fashion industry: China vs. U.S.A. Sustainability 2016, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, C.J. Marketing and organisational development in e-SMEs: Understanding survival and sustainability in growth-oriented and comfort-zone pure-play enterprises in the fashion retail industry. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2012, 8, 165–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, C.J.; Schmidt, R.Ä.; Pioch, E.A.; Hallsworth, A. An approach to sustainable ‘fashion’ e-retail: A five-stage evolutionary strategy for ‘clicks-and-mortar’ and ‘pure-play’ enterprises. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2006, 13, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, C.J.; Schmidt, R.Ä.; Pioch, E.A.; Hallsworth, A. “Web-weaving”: an approach to sustainable e-retail and online advantage in lingerie fashion marketing. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2006, 34, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, A.; Toporowski, W.; Zielke, S. Transport-related CO2, effects of online and brick-and-mortar shopping: A comparison and sensitivity analysis of clothing retailing. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2012, 17, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, P.N. Stages of consumerism: Recent work on the issues of periodization. J. Mod. Hist. 1997, 69, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Verbeke, M. Women, shopping and leisure. Leis. Stud. 1987, 6, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, T.; Bruce, M. Fashion Marketing—Contemporary Issues, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muran, L. Profile of H&M: A pioneer of fast fashion. In Textile Outlook International; Anson, R., Ed.; Textiles Intelligence Ltd.: Wilmslow, UK, 2007; pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, T. Trends in textile global supply chains. Textiles 2010, 37, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, M.O. Fast and Furious. Lat. Trade 2007, 15, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, T. Globalization: Global markets and global supplies. In Fashion Marketing Contemporary Issues, 2nd ed.; Hines, T., Bruce, M., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Where Does Discarded Clothing Go? Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/07/where-does-discarded-clothing-go/374613/ (accessed on 10 April 2017).

- Fast Fashion and the Environment. Available online: http://www.isfoundation.com/news/fast-fashion-and-environment (accessed on 10 April 2017).

- Thomas, S. From green blur to ecofashion: Fashioning an ecolexicon. Fash. Theory J. Dress Body Cult. 2008, 12, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Slow fashion: An invitation for systems change. Fash. Pract. 2010, 2, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H&M Conscious Action Sustainability Report. Available online: http://sustainability.hm.com/content/dam/hm/about/documents/en/CSR/reports/Conscious%20Actions%20Sustainability%20Report%202013_en.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2017).

- Behind the Label: H&M’s Conscious Collection. Available online: http://ecosalon.com/behind-the-label-hms-conscious-collection/ (accessed on 22 June 2017).

- Cline, E.L. Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion; Penguin Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, H. Slow + Fashion—An oxymoron—Or a promise for the future…? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusk, K; Oscar, T.; Geert, L.; Stephan, W. Crafting smart textiles—A meaningful way towards societal sustainability in the fashion field? Nord. Text. J. 2012, 1, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Green Generation: Millennials Say Sustainability Is a Shopping Priority. Available online: http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2015/green-generation-millennials-say-sustainability-is-a-shopping-priority.html (accessed on 5 November 2015).

- Brown, S. Eco Fashion; Laurence King: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.; Ibáñez, V.A.; Sainz, F.J.F. Green branding effects on attitude: Functional versus emotional positioning strategies. Market. Intell. Plan. 2005, 23, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, N.D. The branding of ethical fashion and the consumer: A luxury niche or mass-market reality? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M. Greener Marketing; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- What Is Ecofashion? After Food, Clothing Is the Area of Consumerism that Has the Largest Impact on the Environment. But Is It Possible for Consumers to Make Better Environmental Choices, or Does the Responsibility Rest with the Fashion Industry? Available online: https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-178630741.html (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Joergens, C. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2006, 10, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wang, Y.; Lo, C.K.Y.; Shum, M. The impact of ethical fashion on consumer purchase behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Making environmental communications meaningful to female adolescents: A study in Hong Kong. Sci. Commun. 2008, 30, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Velde, L.; Verbeke, W.; Popp, M.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. The importance of message framing for providing information about sustainability and environmental aspects of energy. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 5541–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husvedt, G.; Dickson, M. Consumer likelihood of purchasing organic cotton apparel: Influences of attitudes and self-identity. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2009, 13, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.J.; Divita, L.; Kim, H.Y. Environmental awareness on bamboo product purchase intentional: Do consumption values impact green consumption? Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2013, 6, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 2: Opportunities for the Consumer Goods Sector. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/TCE_Report-2013.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Choi, T.-M.; Cheng, T.C.E. Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain Management from Sourcing to Retailing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The Worn, the Torn, the Wearable: Textile Recycling in Union Square. Available online: http://bada.hb.se/bitstream/2320/12345/1/NJ2012_Nr2_DG_1209_redigerad%20upp.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Cervellon, M.-C.; Carey, L.; Harms, T. Something old, something used: Determinants of women’s purchase of vintage fashion vs. second-hand fashion. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 956–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Moraes, C.; McEachern, M. From conspicuous to considered fashion: A harm-chain approach to the responsibilities of luxury-fashion businesses. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1277–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denegri-Knott, J.; Molesworth, M. I’ll sell this and I’ll buy them that’: eBay and the management of possessions as stock. J. Consum. Behav. 2009, 8, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiot, D.; Roux, D. A second-hand shoppers’ motivation scale: Antecedents, consequences and implications for retailers. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, H.-M.; Park-Poaps, H. Factors motivating and influencing clothing disposal behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, D.; Korchia, M. Am I what I wear? An exploratory study of symbolic meanings associated with secondhand clothing. Adv. Consum. Res. 2006, 33, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Leipämaaleskinen, H. Pre-loved luxury: identifying the meanings of second-hand luxury possessions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerval, O. Fashion: Concept to Catwalk; Firefly Books: Buffalo, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- H&M Group Sustainability Report 2016. Available online: http://sustainability.hm.com/content/dam/hm/about/documents/en/CSR/2016%20Sustainability%20report/HM_group_SustainabilityReport_2016_FullReport_en.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Rogers, D.S.; Tibben-Lembke, R. An examination of reverse logistics practices. J. Bus. Logist. 2001, 22, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Ellram, L.M. Reverse logistics: A review of the literature and framework for future investigation. J. Bus. Logist. 1998, 19, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.X.; Webster, S. Markdown money contracts for perishable goods with clearance pricing. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 196, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, H.; Yue, X. Trade promotion mode choice and information sharing in fashion retail supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakiraman, N.; Syrdal, H.A.; Freling, R. The effect of return policy leniency on consumer purchase and return decisions: A meta-analytic review. J. Retail. 2016, 92, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifield, C.; Cole, C.; Schultz, R.L. Product returns on the Internet: A case of mixed signals? J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffis, S.E.; Rao, S.; Goldsby, T.J.; Niranjan, T.T. The customer consequences of returns in online retailing: An empirical analysis. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjort, K.; Lantz, B. (R) e-tail borrowing of party dresses: An experimental study. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Paswan, A.; Yan, R. E-tailer’s return policy, consumer’s perception of return policy fairness and purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.L. Remote purchase environments: The influence of return policy leniency on two-stage decision processes. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, B.; Hjort, K. Real e-customer behavioural responses to free delivery and free returns. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 13, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.K.; Setaputra, R. A dynamic model for optimal design quality and return policies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 180, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjort, K.; Lantz, B. The impact of returns policies on profitability: A fashion e-commerce case. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4980–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chircu, A.M.; Mahajan, V. Managing electronic commerce retail transaction costs for customer value. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R. Product categories, returns policy and pricing strategy for e-marketers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2009, 18, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, J.; Frost, R. E-Marketing, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak, R.; Bruce, M. Identification of UK fashion retailer use of websites. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2004, 32, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Clarke-Hill, C.; Hillier, D. (R)etailing in the UK. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2002, 20, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsh, J.; Crawford, B.; Grosso, C. How e-tailing can rise from the ashes. McKinsey Q. 2000, 3, 98–109. Available online: https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1–64333807/how-e-tailing-can-rise-from-the-ashes (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Marshall, P.; Mackay, J. An emergent framework to support visioning and strategy formulation for EC. INFOR J. 2002, 40, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffcoate, J.; Chappell, C.; Feindt, S. Best practice in SME adoption of e-commerce. Benchmarking Int. J. 2002, 9, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Prothero, A. Green consumption life-politics, risk and contradictions. J. Consum. Cult. 2008, 8, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, C; Tanya, B; Gillian, L. Sustainability in Emerging Markets: Lessons from South Africa. Available online: http://www.cimaglobal.com/Documents/Thought_leadership_docs/Sustainability_emerging_markets.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2017).

- Doh, J.P.; Littell, B.; Quigley, N.R. CSR and sustainability in emerging markets: Societal, institutional, and organizational influences. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarthy, B.L.; Jayarathne, P.G.S.A. Sustainable collaborative supply networks in the international clothing industry: A comparative analysis of two retailers. Prod. Plan. Control 2012, 23, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.; Bianchi, L.; Frey, M.; Passetti, E. Sustainability reporting and corporate identity: Action research evidence in an Italian retailing cooperative. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, M.P.S.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organisation and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Shaw, D. Identifying fair trade in consumption choice. J. Strateg. Mark. 2006, 14, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indvik, L. Why Is It Taking Fashion So Long to Get on Board with Sustainability? Available online: http://www.fashionista.com (accessed on 24 May 2016).

- Ritch, E.; Schröder, M.; Brennan, C.; Pretious, M. Sustainable consumption and the retailer: Will fashion ethics follow food? In Readings and Cases in Sustainable Marketing: A strategic Approach to Social Responsibility; D’Souza, C., Taghian, M, Eds.; Tilde University Press: Prahran, Australia, 2011; pp. 176–198. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetto, C.A.D. Corporate social responsibility as an emerging business model in fashion marketing. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Content Areas | Articles |

|---|---|

| Sustainable retailing in disposable fashion, fast fashion, and slow fashion | Bianchi and Birtwistle [14]; Bly et al. [15]; Cortez et al. [16]; Goworek et al. [17]; Joung [18]; Pookulangara and Shephard [19]; Ritch [20]; Shen [21]; Yeung and Ang [22] |

| Green branding and eco-labeling | Bly et al. [15]; Veludo-de-Oliveira et al. [23]; Faust [24]; Fuentes [25]; Fuentes [26]; Fuentes and Fredriksson [27]; Gam [28]; Goworek et al. [17]; Ha-Brookshire and Norum [29]; Hyllegard et al. [30]; Jones et al. [31]; Kumar [32]; Lee et al. [9]; Ritch [20]; Ritch and Schröder [33]; Ryding et al. [34]; Wang et al. [36] |

| Retailing of secondhand fashion | Beh et al. [36]; Bly et al. [15]; Delai and Takahashi [37]; Fuentes [26]; Hvass [38]; Joung [18]; Kumar [32]; Shen [21]; Wilson [39] |

| Reverse logistics in the fashion industry | Beh et al. [36]; Delai and Takahashi [37]; Hvass [38]; Shen [21]; Shen and Li [40]; Shen et al. [41]; Yeung and Ang [22] |

| Emerging opportunities in e-commerce | Ashworth [42]; Ashworth et al. [43]; Ashworth et al. [44]; Bly et al. [15]; Shen [21]; Wiese et al. [45]; Yeung and Ang [22] |

| Author | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Lee et al. [9] | Consumers’ perceptions of green campaigns are positively associated with their sustainability behavior through the mediating effect of consumers’ green consciousness. |

| Bly et al. [15] | Personal style is a critical factor in influencing consumers‘ sustainable fashion behaviors, such as secondhand fashion goods purchases. |

| Goworek et al. [17] | Consumers’ clothing sustainability behaviors are largely dependent on their existing habits and routines, rather than their awareness of sustainable business practices. |

| Ritch [20] | The paper explores the application of sustainability in the fashion industry and finds that the concepts of sustainability have been transferred to the UK fashion retailing and have begun to influence consumers’ decision making. The paper also discovers consumer perceptions of sustainable fashion consumption and finds some barriers to sustainable consumption in the fashion industry. |

| Fuentes and Fredriksson [27] | The practices of sustainable services include not only displaying green products, but also promoting green products to consumers in stores and answering consumers’ sustainability questions. |

| Gam [28] | Consumers’ perceptions of green campaigns are positively associated with their sustainability behaviors through the mediating effect of consumers’ green consciousness. |

| Ha-Brookshire and Norum [29] | Consumers’ willingness to pay for premium or sustainable fashion products is positively affected by their attitudes toward sustainable products and brand name, but negatively influenced by consumers’ attitudes towards the environment, age, and price. |

| Kumar [32] | Practices of sustainable retailing in India include nine core groups, such as promoting sustainable business practices, promoting awareness practices, and consumer involvement approaches. |

| Ritch and Schröder [33] | Professional women in the UK apply heuristics to their fashion consumption behavior. |

| Characteristics | Traditional Online Retailing | Blog Shops |

|---|---|---|

| Governance | Increasingly regulated | Largely unregulated |

| Consumers interface | B2C (Amazon) and C2C (eBay) | B2C |

| Scale | Various sizes | Mostly small |

| Retailing space | From virtual to physical space | From virtual space to bricks and 2mortar |

| Remarks | Well established, dominated by international B2C platforms with highly efficient supply and distribution networks | Newly established, and mostly established by inexperienced young firms in Asia |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Song, Y.; Tong, S. Sustainable Retailing in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071266

Yang S, Song Y, Tong S. Sustainable Retailing in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2017; 9(7):1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071266

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shuai, Yiping Song, and Siliang Tong. 2017. "Sustainable Retailing in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 9, no. 7: 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071266