Mapping Entrepreneurs’ Orientation towards Sustainability in Interaction versus Network Marketing Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

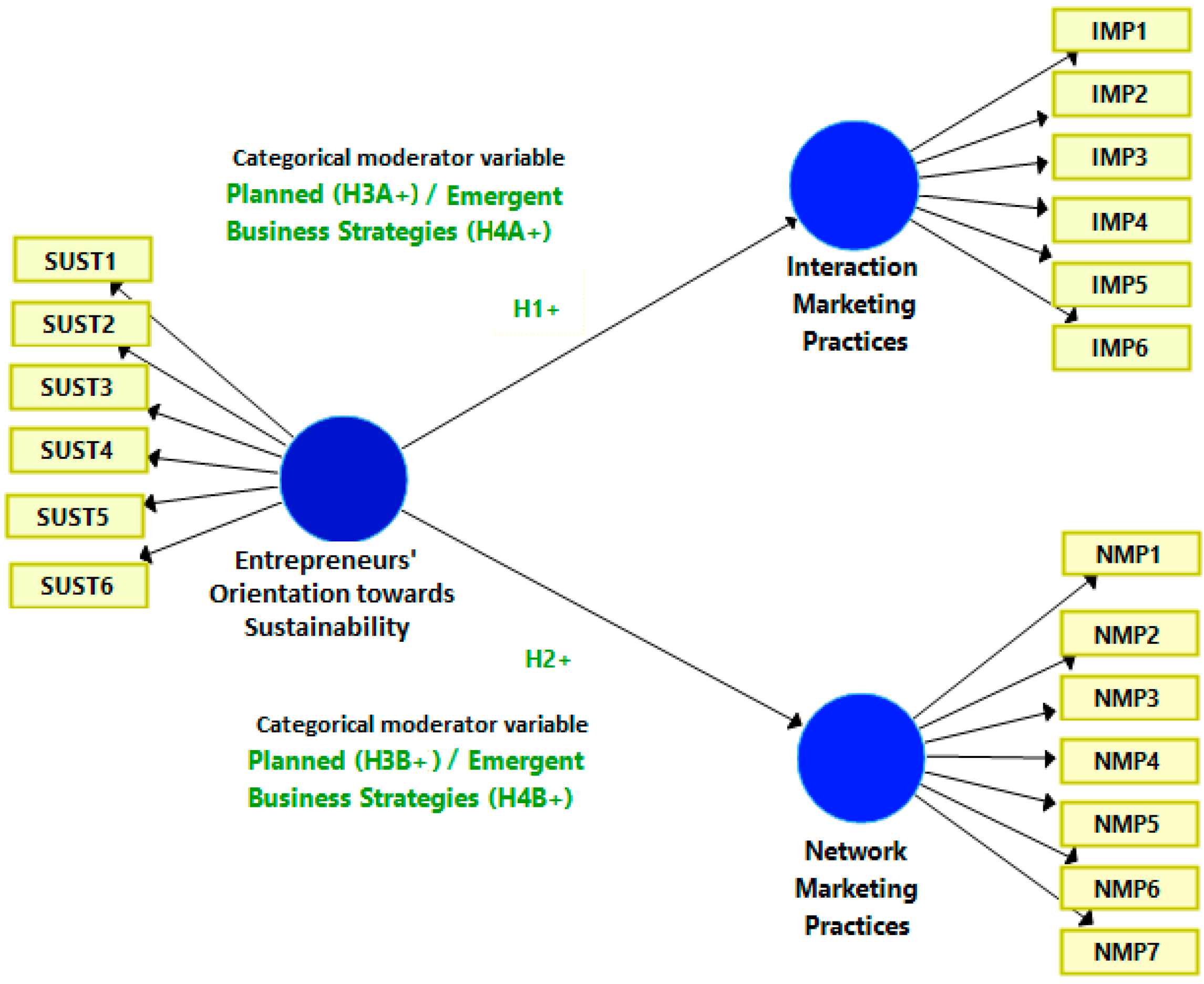

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Contribution and Originality: Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business Models for Sustainability: Origins, Present Research, and Future Avenues. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, W.L.; Crittenden, W.F.; Ferrell, L.K.; Ferrell, O.C.; Pinney, C.C. Market-oriented sustainability: A conceptual framework and propositions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.S. The decline of conceptual articles and implications for knowledge development. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M. Fostering sustainability by linking co-creation and relationship management concepts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapenciuc, C.V.; Pînzaru, F.; Vatamanescu, E.-M.; Stanciu, P. Converging Sustainable Entrepreneurship and the Contemporary Marketing Practices. An Insight into Romanian Start-Ups. Amfiteatru Econ. 2015, 17, 938–954. [Google Scholar]

- Zucchella, A.; Urban, S. Futures of the sustainable firm: An evolutionary perspective. Futures 2014, 63, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Pînzaru, F.; Andrei, A.G.; Zbuchea, A. Investigating SMES Sustainability with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2016, 15, 259–273. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfection, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.09.001 (accessed on 11 July 2017). [CrossRef]

- Soto-Acosta, P.; Cismaru, D.-M.; Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Ciochină, R.S. Sustainable Entrepreneurship in SMEs: A Business Performance Perspective. Sustainability 2016, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubacker, R. The Next Best Thing for Entrepreneurs: Sustainability. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ceibs/2015/09/09/the-next-big-thing-for-entrepreneurs-sustainability/#795309f85aa9 (accessed on 12 July 2017).

- Pădurean, M.A.; Nica, A.M.; Nistoreanu, P. Entrepreneurship in tourism and financing through the Regional Operational Programme. Amfiteatru Econ. 2015, 17, 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chebeň, J.; Lančarič, D.; Savov, R.; Tóth, M.; Tlučhoř, J. Towards Sustainable Marketing: Strategy in Slovak Companies. Amfiteatru Econ. 2015, 17, 855–871. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. Opportunities for cross-border entrepreneurship development in a cluster model exemplified by the Polish-Czech region. Sustainability 2016, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Székely, F.; Knirsch, M. Responsible leadership and corporate social responsibility: Metrics for sustainable performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J. The role of sustainable entrepreneurship in sustainability transitions: A conceptual synthesis against the background of the multi-level perspective. Adm. Sci. 2015, 5, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, K.; Palazzo, G. Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sense-making. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuosmanen, T.; Kuosmanen, N. How not to measure sustainable value (and how one might). Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. The evolution of resource-advantage theory: Six events, six realizations, six contributions. J. Hist. Res. Mark. 2012, 4, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritz, R.; Pretorius, M.; Plant, K. Exploring the Interface between Strategy-Making and Responsible Leadership. J. Bus. Eth. 2011, 98, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, F.; Figge, F.; Hahn, T. Planned or Emergent Strategy Making? Exploring the Formation of Corporate Sustainability Strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 25, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurth, V.; Peck, J.; Jackman, D.; Wensing, E. Reforming Marketing for Sustainability: Towards a Framework for Evolved Marketing; Working Paper; Plymouth University: Plymouth, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coviello, N.; Brodie, R. Contemporary marketing practices of consumer and business-to-business firms: How different are they? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2001, 16, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.; Wilson, H. An Exploratory Case Study Analysis of Contemporary Marketing Practices. J. Strateg. Mark. 2009, 17, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brodie, R.; Coviello, N.; Winklhofer, H. Contemporary marketing practices research program: A review of the first decade. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 23, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choongo, P.; Van Burg, E.; Paas, L.J.; Masurel, E. Factors influencing the identification of sustainable opportunities by SMEs: Empirical evidence from Zambia. Sustainability 2016, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, V.; Brookes, R.; Palmer, R. Research informed teaching and teaching-informed research: The CMP living case study approach to understanding marketing practice. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 23, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, A.; Davis, R.; Brodie, R.J.; Buchanan-Oliver, M. Pluralism in contemporary marketing practices. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2000, 18, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păduraru, T.; Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Andrei, A.G.; Pînzaru, F.; Zbuchea, A.; Maha, L.G.; Boldureanu, G. Sustainability in Relationship Marketing: An Exploratory Model for the Industrial Field. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2016, 15, 1635–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, J. Relationship marketing. In Exploring Relational Strategies in Marketing, 4th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R.M. Relationship marketing and marketing strategy. In Handbook of Relationship Marketing; Sheth, J.N., Parvakiyar, A., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 481–504. [Google Scholar]

- Buttle, F.B. Relationship Marketing Theory and Practice; Paul Chapman: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, A.G.; Zait, A.; Vătămănescu, E.M.; Pînzaru, F. Word-of-mouth generation and brand communication strategy: Findings from an experimental study explored with PLS-SEM. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 478–495. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-11-2015-0487 (accessed on 11 July 2017). [CrossRef]

- Andrei, A.G.; Gazzola, P.; Zbuchea, A.; Alexandru, V.A. Modeling socially responsible consumption and the need for uniqueness: A PLS-SEM approach. Kybernetes 2017, 4. in press. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/K-03-2017-0103 (accessed on 25 July 2017). [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.M.; Nistoreanu, B.G.; Mitan, A. Competition and Consumer Behavior in the Context of the Digital Economy. Amfiteatru Econ. 2017, 19, 354–366. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Okoroafo, S.; Gammoh, B. The Role of Sustainability Orientation in Outsourcing: Antecedents, Practices, and Outcomes. J. Manag. Sustain. 2014, 4, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.H. Examining the effects of green supply chain management practices and their mediations on performance improvements. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “sustainability business model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, G.; Domegan, C. Social Marketing: From Tunes to Symphonies, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Andrei, A.G.; Nicolescu, L.; Pînzaru, F.; Zbuchea, A. The Influence of Competitiveness on SMEs Internationalization Effectiveness. Online versus Offline Business Networking. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2017, 34, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Alexandru, V.-A.; Gorgos, E.-A. The Five Cs Model of Business Internationalization (CMBI)—A preliminary theoretical insight into today’s business internationalization challenges. In Strategica. Management, Finance, and Ethics; Brătianu, C., Zbuchea, A., Pînzaru, F., Vătămănescu, E.-M., Eds.; Tritonic: Bucharest, Romania, 2014; pp. 537–558. [Google Scholar]

- Beachcroft-Shaw, H.; Ellis, D. Social marketing to achieve sustainability. In Collective Creativity for Responsible and Sustainable Business Practice, 1st ed.; Fields, Z., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 296–314. [Google Scholar]

- Bratianu, C.; Bolisani, E. Knowledge Strategy: An Integrated Approach for Managing Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM 2015), Udine, Italy, 3–4 September 2015; Massaro, M., Garlatti, A., Eds.; Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited: Reading, UK, 2015; pp. 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Gabler, C.B.; Panagopoulos, N.; Vlachos, P.A.; Rapp, A. Developing an environmentally sustainable business plan: An international B2B case study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 24, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.; Buckingham, M.; Dekoninck, E.; Cornwell, H. The importance of understanding the business context when planning eco-design activities. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2015, 32, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Rana, P.; Short, S.W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2015, 32, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerwas, C.; Von Korflesch, H.F.O. A conceptual model of entrepreneurial reputation from a venture capitalist’s perspective. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2016, 17, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollin, K.; Christensen, L.B.; Wilke, R. Sustainability in business from a marketing perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2015, 23, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafizad, J. Determinants of relationship marketing by women small business owners. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2017, 29, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. From the Special Issue Guest Editors. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W. Common beliefs and reality about PLS comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Meth. 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advan. Intern. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–320. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications in Marketing and Related Fields; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Using partial least squares path modeling in international advertising research: Basic concepts and recent issues. In Handbook of Research in International Advertising; Okazaki, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; pp. 252–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 16 July 2017).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publication: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (Pls) Approach to Causal Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption and Use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–358. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus Reflective Indicators in Organizational Measure Development: A Comparison and Empirical Illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M. Multi-group analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. Adv. Int. Mark. 2011, 22, 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Schubring, S.; Lorscheid, I.; Meyer, M.; Ringle, C.M. The PLS agent: Predictive modeling with PLS-SEM and agent-based simulation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4604–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurs’ orientation towards sustainability (SUST) (Reflective) | SUST1. Our products and/or services are harmless in terms of societal and environmental issues. | [5,8,12] |

| SUST2. Our products and/or services are liable to generate long-term profit. | [5,8,12] | |

| SUST3. Our products and/or services yield benefits to the larger community. | [5,8,12] | |

| SUST4. 14. It is important for our firm to treat the workforce and partners with the due respect. | [5,8,11,12] | |

| SUST5. It is important for our firm to establish long-term social goals. | [5,8,11,12] | |

| SUST6. 16. It is important for our firm to be actively involved in the community growth. | [5,8,11,12] | |

| Interaction Marketing Practices (IMP) (Reflective) | IMP1. Our marketing activities are intended to develop cooperative relationships with our customers. | [26,28] |

| IMP2. Our marketing planning is focused on issues related to one-to-one relationships with customers in our market(s), or individuals in organizations we deal with. | [26,28] | |

| IMP3. When dealing with our market(s), our purpose is to build a long-term relationship with specific customer(s). | [26,28] | |

| IMP4. Our organization’s contact with our primary customers is interpersonal (e.g., involving one-to-one interaction between people). | [26,28] | |

| IMP5. The type of relationship with our customers is characterized as interpersonal interaction that is ongoing. | [26,28] | |

| IMP6. Our marketing resources (i.e., people, time, and money) are invested in establishing and building personal relationships with individual customers. | [26,28] | |

| Network Marketing Practices (NMP) (Reflective) | NMP1. Our marketing activities are intended to coordinate activities between ourselves, customers, and other parties in our wider marketing system. | [26,28] |

| NMP2. Our marketing planning is focused on issues related to the network of relationships between individuals and organizations in our wider marketing system. | [26,28] | |

| NMP3. When dealing with our market(s), our purpose is to form relationships with a number of organizations in our market(s) or wider marketing system. | [26,28] | |

| NMP4. Our organization’s contact with our primary customers is from impersonal to interpersonal across firms in the broader network. | [26,28] | |

| NMP5. The type of relationship with our customers is characterized as contact with people in our organization and wider marketing system that is ongoing. | [26,28] | |

| NMP6. Our marketing resources (i.e., people, time and money) are invested in developing our organization’s network relationships within our market(s) or wider marketing system. | [26,28] | |

| NMP7. Our marketing communication involves senior managers networking with other managers in a wider marketing system to interact with customers and other organizations in the network. | [26,28] |

| Total Variance Explained | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||||

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 7.692 | 40.482 | 40.482 | 7.692 | 40.482 | 40.482 | 4.727 | 24.881 | 24.881 |

| 2 | 2.563 | 13.491 | 53.973 | 2.563 | 13.491 | 53.973 | 4.106 | 21.613 | 46.494 |

| 3 | 1.354 | 7.128 | 61.101 | 1.354 | 7.128 | 61.101 | 2.775 | 14.607 | 61.101 |

| 4 | 0.969 | 5.099 | 66.200 | ||||||

| 5 | 0.944 | 4.968 | 71.167 | ||||||

| 6 | 0.761 | 4.006 | 75.173 | ||||||

| 7 | 0.652 | 3.431 | 78.604 | ||||||

| 8 | 0.630 | 3.315 | 81.919 | ||||||

| 9 | 0.527 | 2.771 | 84.690 | ||||||

| 10 | 0.467 | 2.459 | 87.149 | ||||||

| 11 | 0.430 | 2.261 | 89.410 | ||||||

| 12 | 0.394 | 2.075 | 91.485 | ||||||

| 13 | 0.353 | 1.858 | 93.343 | ||||||

| 14 | 0.308 | 1.619 | 94.963 | ||||||

| 15 | 0.277 | 1.458 | 96.421 | ||||||

| 16 | 0.258 | 1.358 | 97.779 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.199 | 1.047 | 98.826 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.132 | 0.693 | 99.519 | ||||||

| 19 | 0.091 | 0.481 | 100.000 | ||||||

| Construct | Cronbach Alp Ha | Rho_Alpha | CR | AVE | Indicator | Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurs’ orientation Towards sustainability (Reflective) | 0.874 | 0.881 | 0.904 | 0.612 | SUST1 | 0.743 |

| SUST2 | 0.751 | |||||

| SUST3 | 0.840 | |||||

| SUST4 | 0.741 | |||||

| SUST5 | 0.794 | |||||

| SUST6 | 0.819 | |||||

| Interaction Marketing Practices (IMP) (Reflective) | 0.814 | 0.824 | 0.865 | 0.519 | IMP1 | 0.651 |

| IMP2 | 0.658 | |||||

| IMP3 | 0.803 | |||||

| IMP4 | 0.729 | |||||

| IMP5 | 0.689 | |||||

| IMP6 | 0.777 | |||||

| Network Marketing Practices (NMP) (Reflective) | 0.885 | 0.901 | 0.910 | 0.593 | NMP1 | 0.723 |

| NMP2 | 0.748 | |||||

| NMP3 | 0.837 | |||||

| NMP4 | 0.786 | |||||

| NMP5 | 0.754 | |||||

| NMP6 | 0.846 | |||||

| NMP7 | 0.681 |

| Indicators | SUST | IMP | NMP |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMP1 | 0.464 | 0.651 | 0.448 |

| IMP2 | 0.341 | 0.658 | 0.492 |

| IMP3 | 0.492 | 0.803 | 0.613 |

| IMP4 | 0.402 | 0.729 | 0.409 |

| IMP5 | 0.315 | 0.689 | 0.605 |

| IMP6 | 0.476 | 0.777 | 0.528 |

| NMP1 | 0.271 | 0.476 | 0.723 |

| NMP2 | 0.241 | 0.559 | 0.748 |

| NMP3 | 0.318 | 0.582 | 0.837 |

| NMP4 | 0.291 | 0.537 | 0.786 |

| NMP5 | 0.400 | 0.610 | 0.754 |

| NMP6 | 0.348 | 0.622 | 0.846 |

| NMP7 | 0.216 | 0.389 | 0.681 |

| SUST1 | 0.743 | 0.389 | 0.210 |

| SUST2 | 0.751 | 0.405 | 0.288 |

| SUST3 | 0.840 | 0.470 | 0.239 |

| SUST4 | 0.741 | 0.455 | 0.309 |

| SUST5 | 0.794 | 0.520 | 0.417 |

| SUST6 | 0.819 | 0.494 | 0.362 |

| SUST | IMP | NMP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUST | 0.782 | ||

| IMP | 0.589 | 0.720 | |

| NMP | 0.400 | 0.712 | 0.770 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std. Beta | Std. Dev. | t-Value | Decision | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | SUST −> IMP | 0.589 | 0.095 | 6.213 ** | Supported | 0.347 |

| H2 | SUST −> NMP | 0.400 | 0.101 | 3.942 ** | Supported | 0.160 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std. Beta | Std. Dev. | t-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3A | SUST −> IMP (Planned Business Strategies) | 0.662 | 0.159 | 4.168 ** | Supported |

| H4A | SUST −> NMP (Planned Business Strategies) | 0.491 | 0.146 | 3.364 ** | Supported |

| H3B | SUST −> IMP (Emergent Business Strategies) | 0.593 | 0.108 | 5.471 ** | Supported |

| H4B | SUST −> NMP (Emergent Business Strategies) | 0.383 | 0.146 | 2.630 * | Supported |

| Relationship | Path Coefficients-Diff (g1–g0) | p-Value (g1 vs. g0) |

|---|---|---|

| SUST −> IMP | 0.069 | 0.300 |

| SUST −> NMP | 0.107 | 0.234 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Gazzola, P.; Dincă, V.M.; Pezzetti, R. Mapping Entrepreneurs’ Orientation towards Sustainability in Interaction versus Network Marketing Practices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091580

Vătămănescu E-M, Gazzola P, Dincă VM, Pezzetti R. Mapping Entrepreneurs’ Orientation towards Sustainability in Interaction versus Network Marketing Practices. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091580

Chicago/Turabian StyleVătămănescu, Elena-Mădălina, Patrizia Gazzola, Violeta Mihaela Dincă, and Roberta Pezzetti. 2017. "Mapping Entrepreneurs’ Orientation towards Sustainability in Interaction versus Network Marketing Practices" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091580