Emerging Molecular Technologies in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Liquid Biopsy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

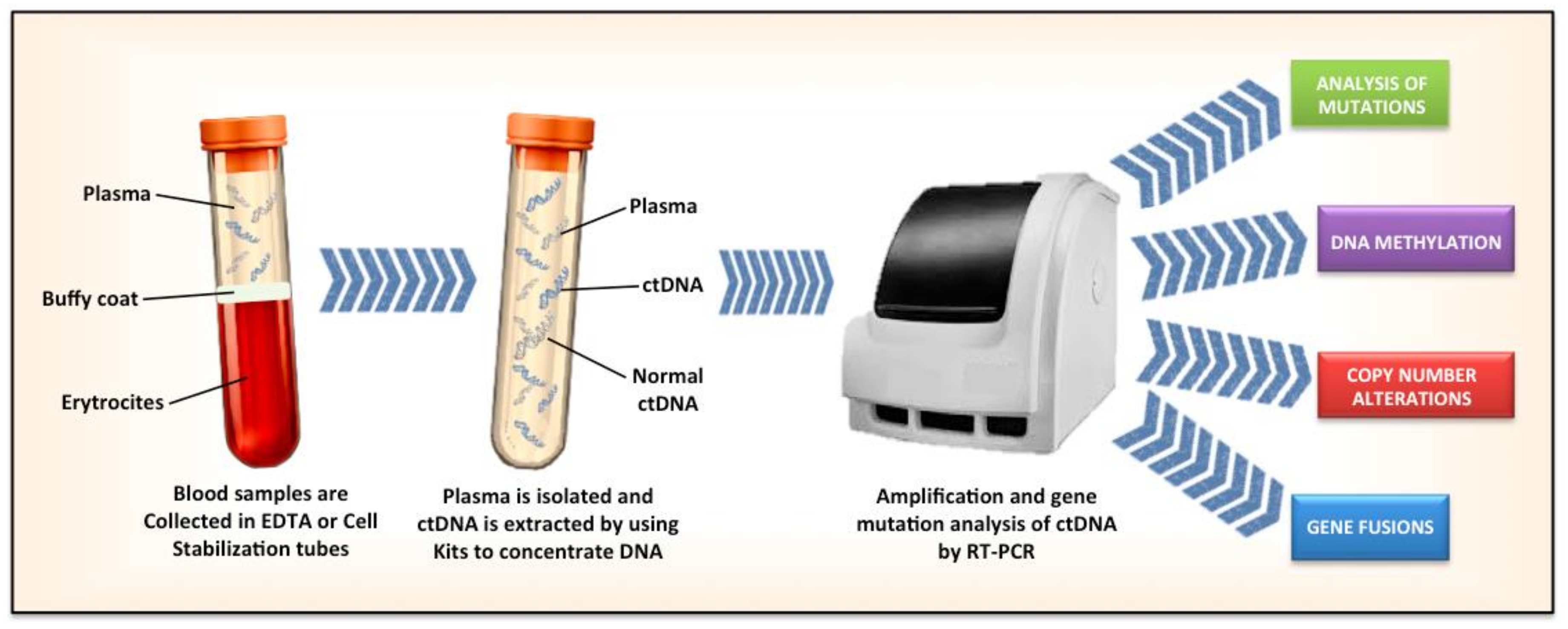

2. Critical Issues Related to ctDNA Assays

3. Concordance between Tissue Based-Biopsy and ctDNA

4. Qualitative Analyses of ctDNA

5. Quantitative Analyses of ccfDNA

6. New Techniques

7. Comparison with CTC Assay

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bergerot, P.G.; Hahn, A.W.; Bergerot, C.D.; Jones, J.; Pal, S.K. The Role of Circulating Tumor DNA in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Opti. Oncol. 2018, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.J.; Purdue, M.P.; Signoretti, S.; Swanton, C.; Albiges, L.; Schmidinger, M.; Heng, D.Y.; Larkin, J.; Ficarra, V. Renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. 2017, 3, 17009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature 2013, 499, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Choueiri, T.K.; Fay, A.P.; Rini, B.I.; Thorner, A.R.; de Velasco, G.; Tyburczy, M.E.; Hamieh, L.; Albiges, L.; Agarwal, N.; et al. Mutations in TSC1, TSC2, and MTOR Are Associated with Response to Rapalogs in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2445–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakimi, A.A.; Ostrovnaya, I.; Reva, B.; Schultz, N.; Chen, Y.B.; Gonen, M.; Liu, H.; Takeda, S.; Voss, M.H.; Tickoo, S.K.; et al. Adverse outcomes in clear cell renal cell carcinoma with mutations of 3p21 epigenetic regulators BAP1 and SETD2: A report by MSKCC and the KIRC TCGA research network. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 3259–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, J.J.; Chen, D.; Wang, P.I.; Marker, M.; Redzematovic, A.; Chen, Y.B.; Selcuklu, S.D.; Weinhold, N.; Bouvier, N.; Huberman, K.H.; et al. Genomic Biomarkers of a Randomized Trial Comparing First-line Everolimus and Sunitinib in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2016, 71, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siravegna, G.; Marsoni, S.; Siena, S.; Bardelli, A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douillard, J.; Ostoros, G.; Cobo, M.; Ciuleanu, T.; Cole, R.; McWalter, G.; Walker, J.; Dearden, S.; Webster, A.; Milenkova, T.; et al. Gefitinib Treatment in EGFR Mutated Caucasian NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014, 9, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukita, Y.; Uchida, J.; Oba, S.; Nishino, K.; Kumagai, T.; Taniguchi, K.; Okuyama, T.; Imamura, F.; Kato, K. Quantitative identification of mutant alleles derived from lung cancer in plasma cell-free DNA via anomaly detection using deep sequencing data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ren, R.; Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Cai, W.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Y.; Su, C.; Zhao, C.; Li, J.; et al. Peripheral blood for epidermal growth factor receptor mutation detection in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Transl. Oncol. 2014, 7, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.; Wu, Y.L.; Lee, J.S.; Yu, C.J.; Sriuranpong, V.; Sandoval-Tan, J.; Ladrera, G.; Thongprasert, S.; Srimuninnimit, V.; Liao, M.; et al. Detection and dynamic changes of EGFR mutations from circulating tumor DNA as a predictor of survival outcomes in NSCLC Patients treated with first-line intercalated erlotinib and chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3196–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxnard, G.R.; Paweletz, C.P.; Kuang, Y.; Mach, S.L.; O’Connell, A.; Messineo, M.M.; Luke, J.J.; Butaney, M.; Kirschmeier, P.; Jackman, D.M.; et al. Noninvasive detection of response and resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer using quantitative next-generation genotyping of cell-free plasma DNA. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1698–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.X.; Fu, Q.; Guo, Y.Y.; Ye, M.; Zhao, H.X.; Wang, Q.; Peng, X.M.; Li, Q.W.; Wang, R.L.; Xiao, W.H. Effectiveness of circulating tumor DNA for detection of KRAS gene mutations in colorectal cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Onco. Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merker, J.D.; Oxnard, G.R.; Compton, C.; Diehn, M.; Hurley, P.; Lazar, A.J.; Lindeman, N.; Lockwood, C.M.; Rai, A.J.; Schilsky, R.L.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis in patients with cancer: American society of clinical oncology and college of American pathologists joint review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 1242–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellert, H.; Foreman, T.; Jackson, L.; Maar, D.; Thurston, S.; Koch, K.; Weaver, A.; Cooper, S.; Dupuis, N.; Sathyanarayana, U.G.; et al. Development and Clinical Utility of a Blood-Based Test Service for the Rapid Identification of Actionable Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. J. Mol. Diagn. 2017, 19, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, J. Illumina Spin-off to Develop Early-Detection Test. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanman, R.B.; Mortimer, S.A.; Zill, O.A.; Sebisanovic, D.; Lopez, R.; Blau, S.; Collisson, E.A.; Divers, S.G.; Hoon, D.S.; Kopetz, E.S.; et al. Analytical and clinical validation of a digital sequencing panel for quantitative, highly accurate evaluation of cell-free circulating tumor DNA. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxnard, G.R.; Paweletz, C.P.; Sholl, L.M. Genomic analysis of plasma cell-free DNA in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuderer, N.M.; Burton, K.A.; Blau, S.; Rose, A.L.; Parker, S.; Lyman, G.H.; Blau, C.A. Comparison of 2 Commercially Available Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms in Oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettegowda, C.; Sausen, M.; Leary, R.J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Agrawal, N.; Bartlett, B.R.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Alani, R.M.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E.S.; Rizos, H.; Reid, A.L.; Boyd, S.C.; Pereira, M.R.; Lo, J.; Tembe, V.; Freeman, J.; Lee, J.H.; Scolyer, R.A.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA to monitor treatment response and detect acquired resistance in patients with metastatic melanoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 42008–42018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iijima, Y.; Hirotsu, Y.; Amemiya, K.; Ooka, Y.; Mochizuki, H.; Oyama, T.; Nakagomi, T.; Uchida, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Tsutsui, T.; et al. Very early response of circulating tumour–derived DNA in plasma predicts efficacy of nivolumab treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 86, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.W.; Gorin, M.A.; Guner, G.; Pierorazio, P.M.; Netto, G.; Paller, C.J.; Hammers, H.J.; Diaz, L.A.; Allaf, M.E. Circulating Tumor DNA as a marker of therapeutic response in patients with renal cell carcinoma: A pilot study. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2016, 14, e515–e520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Forbes, M.E.; Bitting, R.L.; O’Neill, S.S.; Chou, P.C.; Topaloglu, U.; Miller, L.D.; Hawkins, G.A.; Grant, S.C.; DeYoung, B.R.; et al. Incorporating blood-based liquid biopsy information into cancer staging: Time for a TNMB system? Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, A.W.; Gill, D.M.; Maughan, B.; Agarwal, A.; Arjyal, L.; Gupta, S.; Streeter, J.; Bailey, E.; Pal, S.K.; Agarwal, N. Correlation of genomic alterations assessed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) of tumor tissue DNA and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Potential clinical implications. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 33614–33620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, Y.K.; Davis, A.A.; Carneiro, B.A.; Chandra, S.; Mohindra, N.; Kalyan, A.; Kaplan, J.; Matsangou, M.; Pai, S.; Costa, R.; et al. Concordance between genomic alterations assessed by next-generation sequencing in tumor tissue or circulating cell-free DNA. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 65364–65373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Sonpavde, G.; Agarwal, N.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Srinivas, S.; Haas, N.B.; Signoretti, S.; McGregor, B.A.; Jones, J.; Lanman, R.B.; et al. Evolution of circulating tumor DNA profile from First-line to subsequent therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.M.; Park, H.S.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Ali, S.M.; Greenbowe, J.R.; Yang, I.S.; Kwon, N.J.; Lee, J.L.; Ryu, M.H.; et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals somatic mutations that confer exceptional response to everolimus. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 10547–10556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, M.H.; Hakimi, A.A.; Pham, C.G.; Brannon, A.R.; Chen, Y.B.; Cunha, L.F.; Akin, O.; Liu, H.; Takeda, S.; Scott, S.N.; et al. Tumor genetic analyses of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and extended benefit from mTOR inhibitor therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piva, F.; Santoni, M.; Matrana, M.R.; Satti, S.; Giulietti, M.; Occhipinti, G.; Massari, F.; Cheng, L.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Scarpelli, M.; et al. BAP1, PBRM1 and SETD2 in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma: Molecular diagnostics and possible targets for personalized therapies. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2015, 15, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimadamore, A.; Gasparrini, S.; Santoni, M.; Cheng, L.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Battelli, N.; Massari, F.; Giunchi, F.; Fiorentino, M.; Scarpelli, M.; et al. Biomarkers of aggressiveness in genitourinary tumors with emphasis on kidney, bladder, and prostate cancer. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2018, 18, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.J.; Le, V.; Cao, D.; Cheng, E.H.; Creighton, C.J. Genomic classifications of renal cell carcinoma: A critical step towards the future application of personalized kidney cancer care with pan-omics precision. J. Pathol. 2018, 244, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.K.; Ali, S.M.; Yakirevich, E.; Geynisman, D.M.; Karam, J.A.; Elvin, J.A.; Frampton, G.M.; Huang, X.; Lin, D.I.; Rosenzweig, M.; et al. Characterization of clinical cases of advanced papillary renal cell carcinoma via comprehensive genomic profiling. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menko, F.H.; Maher, E.R.; Schmidt, L.S.; Middelton, L.A.; Aittomäki, K.; Tomlinson, I.; Richard, S.; Linehan, W.M. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): Renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam. Cancer 2014, 13, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qassab, U.; Lorentz, C.A.; Laganosky, D.; Ogan, K.; Master, V.; Pattaras, J.; Issa, M.; Keith, C.; Roberts, D.; Rossi, M.; et al. (PNFBA-12) Liquid biopsy for renal cell carcinoma. J. Urol. 2017, 197, e913–e914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.M.; Rainer, T.H.; Chan, L.Y.; Hjelm, N.M.; Cocks, R.A. Plasma DNA as a prognostic marker in trauma patients. Clin. Chem. 2000, 46, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, A.; Wort, S.J.; Thomas, H.; Collinson, P.; Bennett, E.D. Plasma DNA concentration as a predictor of mortality and sepsis in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2006, 10, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.P.Y.; Chia, R.H.; Wu, T.L.; Tsao, K.C.; Sun, C.F.; Wu, J.T. Elevated cell-free serum DNA detected in patients with myocardial infarction. Clin. Chim. Acta 2003, 327, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Busch, J.; Jung, M.; Rabenhorst, S.; Ralla, B.; Kilic, E.; Mergemeier, S.; Budach, N.; Fendler, A.; Jung, K. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of circulating cell-free genomic and mitochondrial DNA fragments in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2016, 452, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.; Zahalka, T.; Ellinger, J.; Fechner, G.; Heukamp, L.C.; Von Ruecker, A.; Müller, S.C.; Bastian, P.J. Cell-free circulating DNA: Diagnostic value in patients with renal cell cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010, 30, 2785–2789. [Google Scholar]

- Skrypkina, I.; Tsyba, L.; Onyshchenko, K.; Morderer, D.; Kashparova, O.; Nikolaienko, O.; Panasenko, G.; Vozianov, S.; Romanenko, A.; Rynditch, A. Concentration and Methylation of Cell-Free DNA from Blood Plasma as Diagnostic Markers of Renal Cancer. Dis. Markers 2016, 2016, 3693096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.; Zahalka, T.; Fechner, G.; Müller, S.C.; Ellinger, J. Serum DNA hypermethylation in patients with kidney cancer: Results of a prospective study. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 4651–4656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.; Ellinger, J.; Gevensleben, H.; Syring, I.; Lüders, C.; de Vos, L.; Pützer, S.; Bootz, F.; Landsberg, J.; Kristiansen, G.; et al. Cell-Free SHOX2 DNA Methylation in Blood as a Molecular Staging Parameter for Risk Stratification in Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Clin. Chem. 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, K. Monitoring of plasma cell-free DNA in predicting postoperative recurrence of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Int. 2013, 91, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, G.; Ye, X.; Fang, F.; Pu, C.; Huang, H.; Li, G. Quantification of plasma cell-free DNA in predicting therapeutic efficacy of sorafenib on metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Dis. Markers 2013, 34, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Uemura, M.; Fujita, M.; Maejima, K.; Koh, Y.; Matsushita, M.; Nakano, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Wang, C.; Ishizuya, Y.; et al. Clinical significance of the mutational landscape and fragmentation of circulating-tumor DNA in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.Y.; Singhania, R.; Fehringer, G.; Chakravarthy, A.; Roehrl, M.H.A.; Chadwick, D.; Zuzarte, P.C.; Borgida, A.; Wang, T.T.; Li, T.; et al. Sensitive tumour detection and classification using plasma cell-free DNA methylomes. Nature 2018, 563, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhacker, M.; Schmidt, B. Circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) and cancer—A survey. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1775, 181–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.J.; Tsui, D.W.; Murtaza, M.; Biggs, H.; Rueda, O.M.; Chin, S.F.; Dunning, M.J.; Gale, D.; Forshew, T.; Mahler-Araujo, B.; et al. Analysis of Circulating Tumor DNA to Monitor Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Magi-Galluzzi, C. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in renal neoplasms. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2014, 21, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, J.L.; Peng, Z.; Evans, M.F.; Naud, S.; Cooper, K. Sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma is an example of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 64, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, I.; Gauler, T.C.; Bublitz, K.; Lazaridis, L.; Goergens, A.; Giebel, B.; Schuler, M.; Hoffmann, A.C. Circulating tumor cell composition in renal cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hou, S.; Hu, S.; Wu, J.; Jing, Y.; Sun, H.; Yu, F.; Zhao, L.; et al. Combined cell surface carbonic anhydrase 9 and CD147 antigens enable high-efficiency capture of circulating tumor cells in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 59877–59891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, R.B.; Chabner, B.A. Application of Cell-free DNA Analysis to Cancer Treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1754–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitzer, E.; Haque, I.S.; Roberts, C.E.; Speicher, M.R. Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cimadamore, A.; Gasparrini, S.; Massari, F.; Santoni, M.; Cheng, L.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Scarpelli, M.; Montironi, R. Emerging Molecular Technologies in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Liquid Biopsy. Cancers 2019, 11, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020196

Cimadamore A, Gasparrini S, Massari F, Santoni M, Cheng L, Lopez-Beltran A, Scarpelli M, Montironi R. Emerging Molecular Technologies in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Liquid Biopsy. Cancers. 2019; 11(2):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020196

Chicago/Turabian StyleCimadamore, Alessia, Silvia Gasparrini, Francesco Massari, Matteo Santoni, Liang Cheng, Antonio Lopez-Beltran, Marina Scarpelli, and Rodolfo Montironi. 2019. "Emerging Molecular Technologies in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Liquid Biopsy" Cancers 11, no. 2: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020196

APA StyleCimadamore, A., Gasparrini, S., Massari, F., Santoni, M., Cheng, L., Lopez-Beltran, A., Scarpelli, M., & Montironi, R. (2019). Emerging Molecular Technologies in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Liquid Biopsy. Cancers, 11(2), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020196