Visible-Light-Active TiO2-Based Hybrid Nanocatalysts for Environmental Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Synthesis

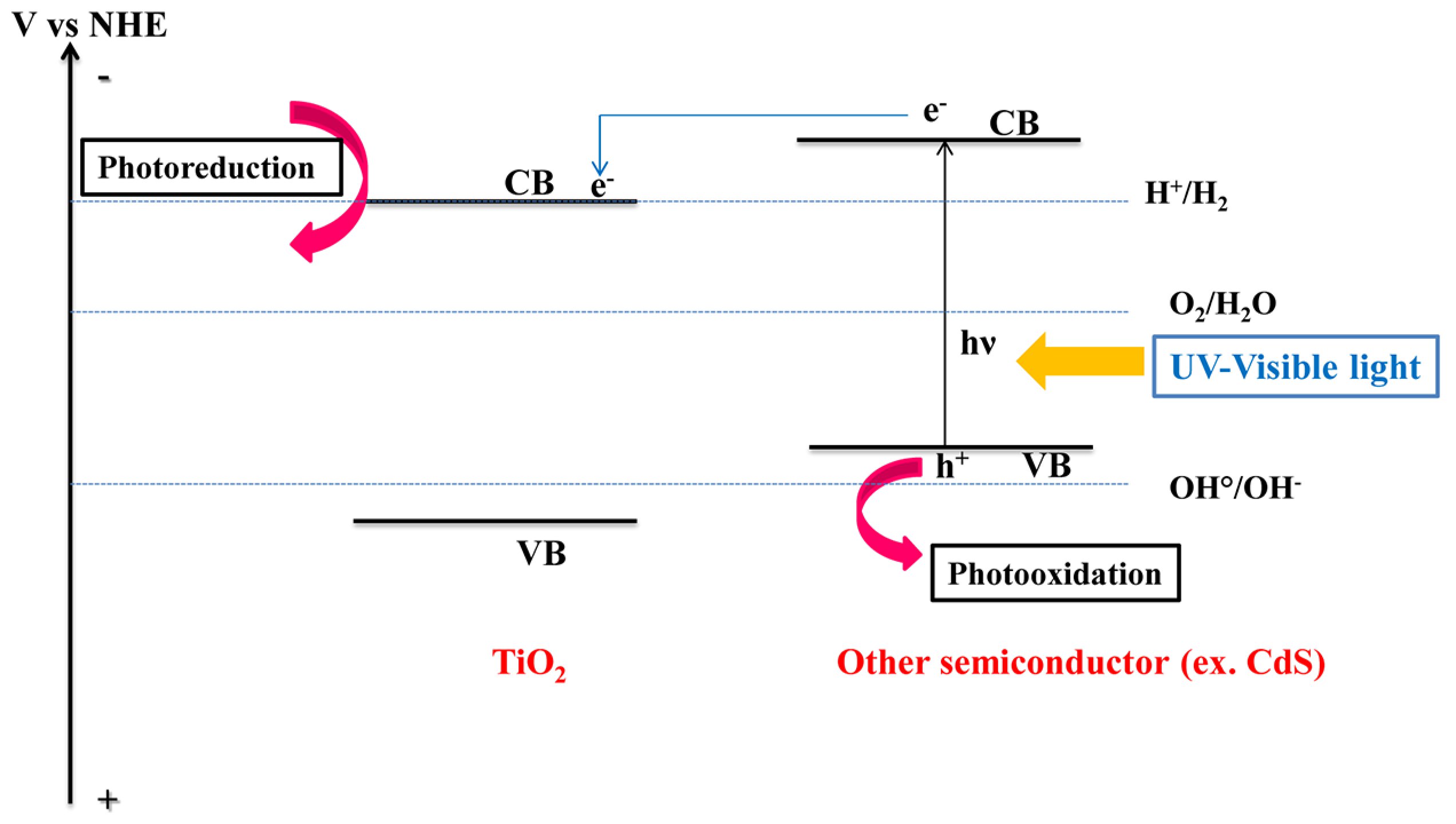

2.1. TiO2/Semiconductor Hybrid Nanocrystals

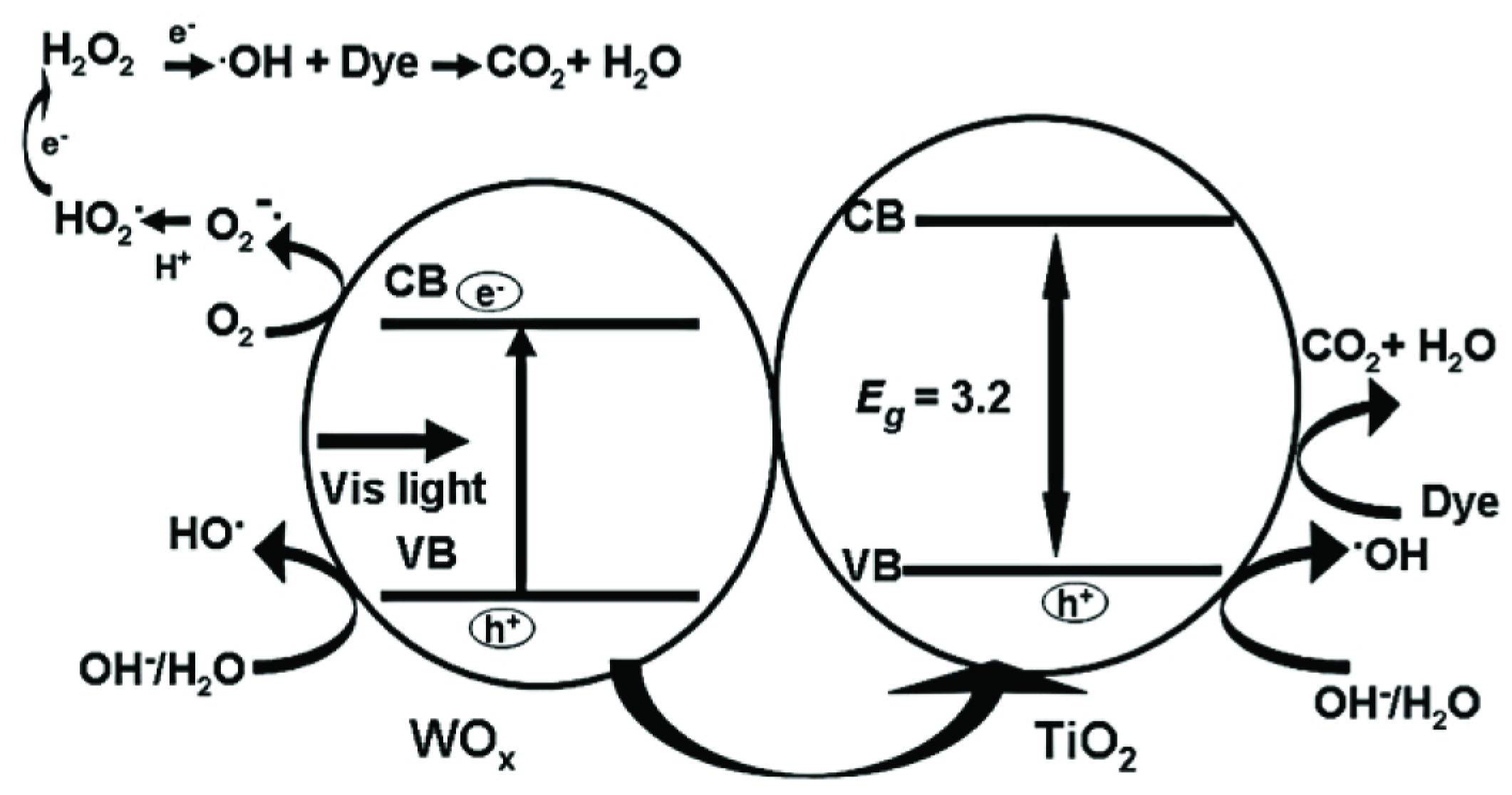

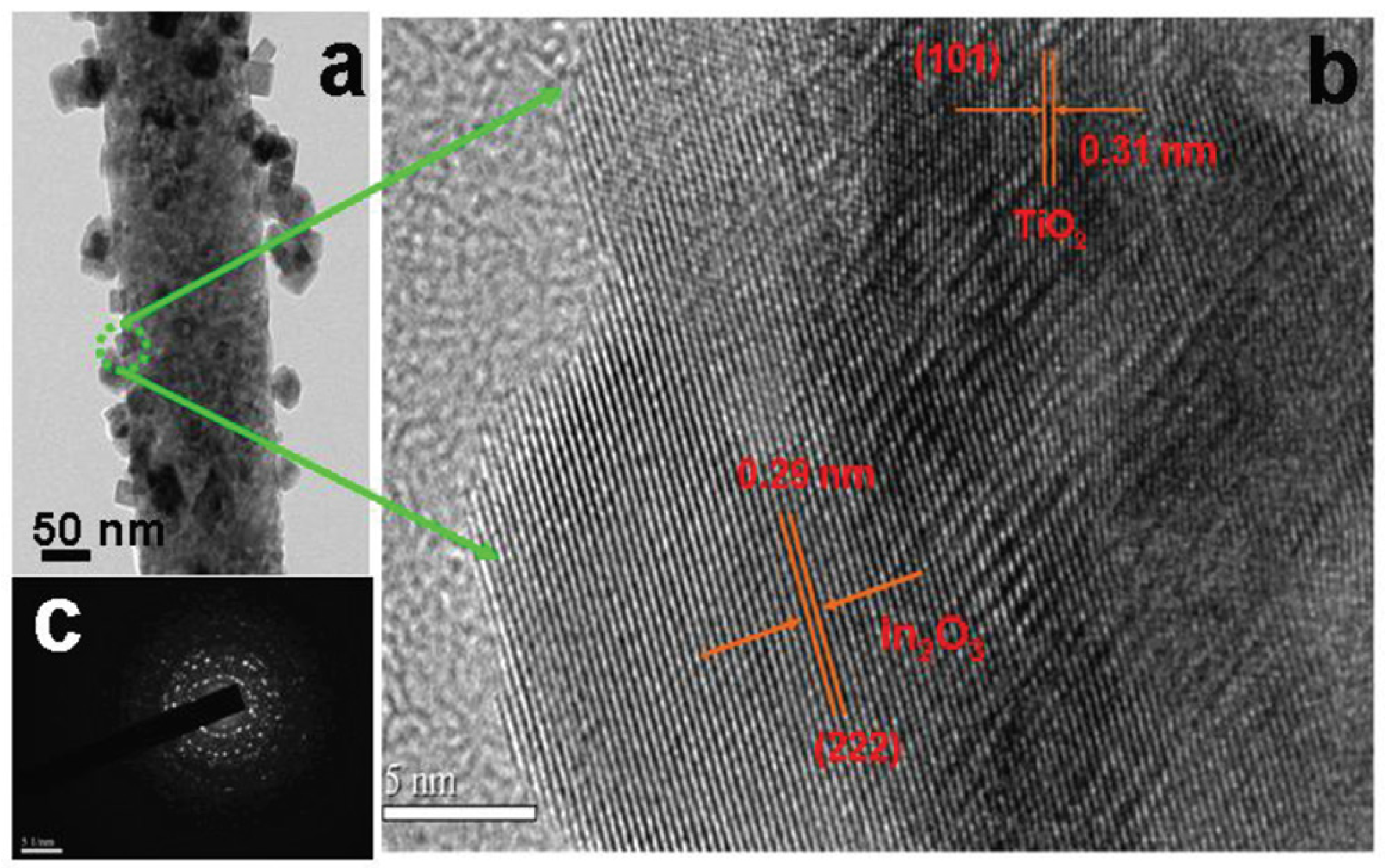

2.1.1. MxOy/TiO2-Based Hybrid Nanocrystals

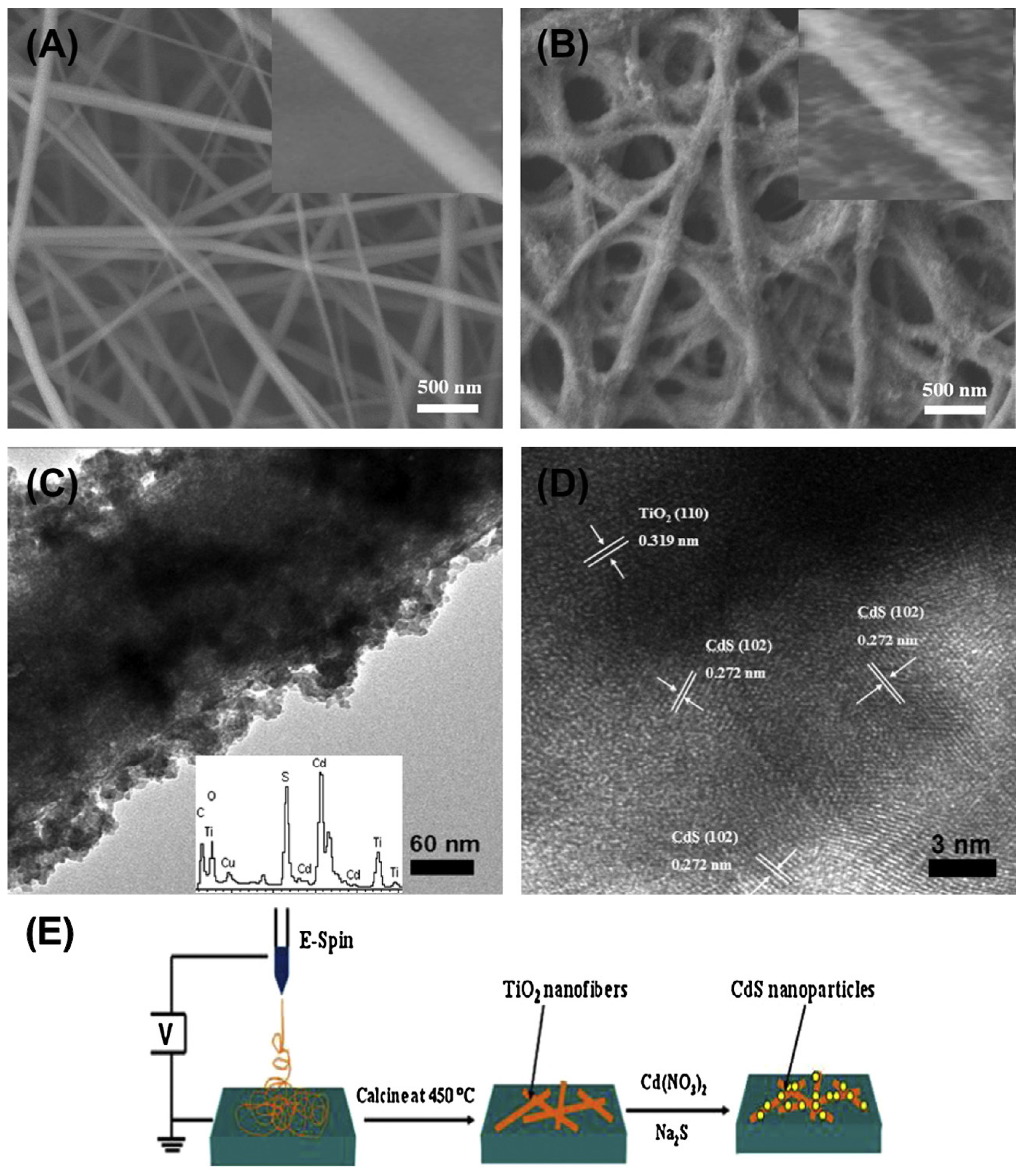

2.1.2. MxSy/TiO2-Based Hybrid Nanocrystals

2.2. TiO2/Plasmonic Material-Based Hybrid Nanocrystals

- far-field effect: an efficient scattering can be mediated by surface plasmon resonance, which increases the optical path of photons in TiO2 that improve the excitation of e−/h+ pairs [65].

2.2.1. Chemical Reduction of Metals at the TiO2 Surface

2.2.2. Photochemical Reduction of Metals at the TiO2 Surface

2.2.3. Growth of a TiO2 Shell at a Plasmonic Nanoparticle Surface

2.2.4. Other Approaches

2.3. TiO2-Based Hybrid Nanocrystals, Including Magnetic Nanoparticles

2.4. Heterostructures Containing C-Based Materials

2.4.1. CNTs-TiO2-Based Heterostructures

2.4.2. Graphene-TiO2-Based Heterostructures

2.4.3. Other C-Based TiO2 Heterostructures

3. Applications

3.1. Water Remediation

3.2. Photocatalytic Removal of Atmospheric Pollutants

3.2.1. Photocatalytic Degradation of NOx

3.2.2. Photocatalytic Degradation of VOCs

3.3. Self-Cleaning Surfaces

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pelaez, M.; Nolan, N.T.; Pillai, S.C.; Seery, M.K.; Falaras, P.; Kontos, A.G.; Dunlop, P.S.M.; Hamilton, J.W.J.; Byrne, J.A.; O’Shea, K.; et al. A review on the visible light active titanium dioxide photocatalysts for environmental applications. Appl. Catal. B 2012, 125, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronella, F.; Truppi, A.; Ingrosso, C.; Placido, T.; Striccoli, M.; Curri, M.L.; Agostiano, A.; Comparelli, R. Nanocomposite materials for photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. Catal. Today 2017, 281, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mao, S.S. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: Synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2891–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Shen, S.; Guo, L.; Mao, S.S. Semiconductor-based photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6503–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, J.; Dunlop, P.; Hamilton, J.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Polo-López, I.; Sharma, P.; Vennard, A. A review of heterogeneous photocatalysis for water and surface disinfection. Molecules 2015, 20, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibhadon, A.; Fitzpatrick, P. Heterogeneous photocatalysis: Recent advances and applications. Catalysts 2013, 3, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-H.; Huang, C.-W.; Wu, J.C.S. Hydrogen production from semiconductor-based photocatalysis via water splitting. Catalysts 2012, 2, 490–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, M.; Varghese, S.; Nair, S. Photocatalytic water treatment by titanium dioxide: Recent updates. Catalysts 2012, 2, 572–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, Y. Application of TiO2 photocatalysis for air treatment: Patents’ overview. Appl. Catal. B 2010, 99, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwi, J.; Pulgarin, C. Innovative self-cleaning and bactericide textiles. Catal. Today 2010, 151, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronella, F.; Pagliarulo, A.; Striccoli, M.; Calia, A.; Lettieri, M.; Colangiuli, D.; Curri, M.; Comparelli, R. Colloidal nanocrystalline semiconductor materials as photocatalysts for environmental protection of architectural stone. Crystals 2017, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparelli, R.; Fanizza, E.; Curri, M.L.; Cozzoli, P.D.; Mascolo, G.; Passino, R.; Agostiano, A. Photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by organic-capped anatase TiO2 nanocrystals immobilized onto substrates. Appl. Catal. B 2005, 55, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fittipaldi, M.; Curri, M.L.; Comparelli, R.; Striccoli, M.; Agostiano, A.; Grassi, N.; Sangregorio, C.; Gatteschi, D. A multifrequency EPR study on organic-capped anatase TiO2 nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 6221–6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panniello, A.; Curri, M.L.; Diso, D.; Licciulli, A.; Locaputo, V.; Agostiano, A.; Comparelli, R.; Mascolo, G. Nanocrystalline TiO2 based films onto fibers for photocatalytic degradation of organic dye in aqueous solution. Appl. Catal. B 2012, 121–122, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsebigler, A.L.; Lu, G.; Yates, J.T. Photocatalysis on TiO2 surfaces: Principles, mechanisms, and selected results. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Lopez-Puente, V.; Wang, Q.; Polavarapu, L.; Pastoriza-Santos, I.; Xu, Q.-H. Plasmon-enhanced light harvesting: Applications in enhanced photocatalysis, photodynamic therapy and photovoltaics. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 29076–29097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronella, F.; Curri, M.L.; Striccoli, M.; Fanizza, E.; Mateo-Mateo, C.; Alvarez-Puebla, R.A.; Sibillano, T.; Giannini, C.; Correa-Duarte, M.A.; Comparelli, R. Direct growth of shape controlled TiO2 nanocrystals onto SWCNTs for highly active photocatalytic materials in the visible. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 178, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shahar, Y.; Banin, U. Hybrid semiconductor–metal nanorods as photocatalysts. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murgolo, S.; Petronella, F.; Ciannarella, R.; Comparelli, R.; Agostiano, A.; Curri, M.L.; Mascolo, G. UV and solar-based photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants by nano-sized TiO2 grown on carbon nanotubes. Catal. Today 2015, 240, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronella, F.; Truppi, A.; Sibillano, T.; Giannini, C.; Striccoli, M.; Comparelli, R.; Curri, M.L. Multifunctional TiO2/FexOy/Ag based nanocrystalline heterostructures for photocatalytic degradation of a recalcitrant pollutant. Catal. Today 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, L.; Cozzoli, P.D. Colloidal heterostructured nanocrystals: Synthesis and growth mechanisms. Nano Today 2010, 5, 449–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casavola, M.; Buonsanti, R.; Caputo, G.; Cozzoli, P.D. Colloidal strategies for preparing oxide-based hybrid nanocrystals. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2008, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzoli, P.D.; Pellegrino, T.; Manna, L. Synthesis, properties and perspectives of hybrid nanocrystal structures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Lu, S.; Tao, X.; Che, Y.; Chen, J.-F. Visible-light-responsive TiO2-coated ZnO:I nanorod array films with enhanced photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6093–6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthina, V.; Correa Baena, J.P.; Liu, G.; Agrios, A.G. ZnO–TiO2 nanocomposite films for high light harvesting efficiency and fast electron transport in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 23864–23870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costi, R.; Saunders, A.E.; Banin, U. Colloidal hybrid nanostructures: A new type of functional materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4878–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts: Design, construction, and photocatalytic performances. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5234–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daghrir, R.; Drogui, P.; Robert, D. Modified TiO2 for environmental photocatalytic applications: A review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 3581–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Luo, S.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Kang, Q.; Cai, Q. High efficient photocatalytic degradation of p-nitrophenol on a unique Cu2O/TiO2 p-n heterojunction network catalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7641–7646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Shifu, C.; Sujuan, Z.; Wei, Z.; Huaye, Z.; Xiaoling, Y. Preparation and characterization of p-n heterojunction photocatalyst p-CuBi2O4/n-TiO2 with high photocatalytic activity under visible and UV light irradiation. J. Nanopart. Res. 2010, 12, 1355–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.-I.; Park, S.-M.; Kang, M. A p-n heterojunction NiS-sensitized TiO2 photocatalytic system for efficient photoreduction of carbon dioxide to methane. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cai, W.; Long, M.; Zhou, B.; Wu, Y.; Wu, D.; Feng, Y. Synthesis of visible-light responsive graphene oxide/TiO2 composites with p/n heterojunction. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 6425–6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Yang, B.; Xiao, T.; Yan, Z. One-step solvothermal synthesis of hierarchically porous nanostructured CdS/TiO2 heterojunction with higher visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 283, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Chen, B.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Shao, C.; Liu, Y. Enhancement of the visible-light photocatalytic activity of In2O3–TiO2 nanofiber heteroarchitectures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 4, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, G.; Gao, Y.; Yin, J.; Xing, A.; Liu, H. Synthesis of high activity TiO2/WO3 photocatalyst via environmentally friendly and microwave assisted hydrothermal process. J. Chem. Soc. Pak. 2011, 33, 666–679. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, S.; Yang, L.; Luo, S.; Cai, Q. Fabrication, characterization and photoelectrochemical properties of Fe2O3 modified TiO2 nanotube arrays. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 7385–7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, M.; Liu, Y.; Yin, Y. Composite titanium dioxide nanomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9853–9889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajjad, A.K.L.; Shamaila, S.; Tian, B.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J. Comparative studies of operational parameters of degradation of azo dyes in visible light by highly efficient WOx/TiO2 photocatalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Guo, Z.; Yu, W.; Zhu, Z. Three-dimensional TiO2/Bi2WO6 hierarchical heterostructure with enhanced visible photocatalytic activity. IET Micro Nano Lett. 2014, 9, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Lin, Y.-H.; Zhang, B.-P.; Li, J.-F.; Nan, C.-W. BiFeO3/TiO2 core-shell structured nanocomposites as visible-active photocatalysts and their optical response mechanism. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 054310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, G. Synthesis and photoinduced charge-transfer properties of a ZnFe2O4-sensitized TiO2 nanotube array electrode. Langmuir 2011, 27, 3113–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, F.; Ehsan, M.F.; Liu, W.; He, T. Visible-light photocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide into methane using Cu2O/TiO2 hollow nanospheres. Chin. J. Chem. 2015, 33, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, N.; Tang, Z.-R.; Xu, Y.-J. Synthesis of one-dimensional CdS@TiO2 core–shell nanocomposites photocatalyst for selective redox: The dual role of TiO2 shell. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 6378–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Luo, S.; Liu, C.; Meng, D.; Ding, M.; Zeng, G. Hierarchical heterostructure of CdS nanoparticles sensitized electrospun TiO2 nanofibers with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 122, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.Y. Facile synthesis of ultrafine CuS nanocrystalline/TiO2: Fe nanotubes hybrids and their photocatalytic and Fenton-like photocatalytic activities in the dye degradation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 227, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Li, Z.; Feng, Z.C.; Li, C. In situ loading of CuS nanoflowers on rutile TiO2 surface and their improved photocatalytic performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 370, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, X.; Zhao, Q.; Ke, J.; Tadé, M.; Liu, S. Preparation of AgInS2/TiO2 composites for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of gaseous o-dichlorobenzene under visible light. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 185, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Cronin, S.B. A review of surface plasmon resonance-enhanced photocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 1612–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sio, L.; Placido, T.; Comparelli, R.; Lucia Curri, M.; Striccoli, M.; Tabiryan, N.; Bunning, T.J. Next-generation thermo-plasmonic technologies and plasmonic nanoparticles in optoelectronics. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2015, 41, 23–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placido, T.; Aragay, G.; Pons, J.; Comparelli, R.; Curri, M.L.; Merkoçi, A. Ion-directed assembly of gold nanorods: A strategy for mercury detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Placido, T.; Comparelli, R.; Giannici, F.; Cozzoli, P.D.; Capitani, G.; Striccoli, M.; Agostiano, A.; Curri, M.L. Photochemical synthesis of water-soluble gold nanorods: The role of silver in assisting anisotropic growth. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 4192–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuno, Y.; Nishioka, K.; Kiya, A.; Nakashima, N.; Ishibashi, A.; Niidome, Y. Uniform and controllable preparation of Au-Ag core–shell nanorods using anisotropic silver shell formation on gold nanorods. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Kou, X.; Yang, Z.; Ni, W.; Wang, J. Shape- and size-dependent refractive index sensitivity of gold nanoparticles. Langmuir 2008, 24, 5233–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J. Shape dependent full width at half maximum of the absorption band in gold nanorods. Phys. Lett. A 2005, 339, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparelli, R.; Placido, T.; Depalo, N.; Fanizza, E.; Striccoli, M.; Curri, M.L. Active Plasmonic Nanomaterials; Pan Stanford Publishing: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 33–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, T.; Kamat, P.V. Charge separation and catalytic activity of Ag@TiO2 core–shell composite clusters under UV–irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3928–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Z.; Ke, X.; Jaatinen, E.; Zhao, J.; Guo, C.; Xie, T.; Wang, D. Mechanism of supported gold nanoparticles as photocatalysts under ultraviolet and visible light irradiation. Chem. Commun. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabatzis, I.M.; Stergiopoulos, T.; Andreeva, D.; Kitova, S.; Neophytides, S.G.; Falaras, P. Characterization and photocatalytic activity of Au/TiO2 thin films for azo-dye degradation. J. Catal. 2003, 220, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumajdad, A.; Madkour, M. Understanding the superior photocatalytic activity of noble metals modified titania under UV and visible light irradiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 7146–7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Shen, J.; Lin, B.; Li, C. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of interlayer-isolated triplex Ag@SiO2@TiO2 core–shell nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 3359–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odom, T.W.; Schatz, G.C. Introduction to plasmonics. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3667–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska, E.; Mahaney, O.O.P.; Abe, R.; Ohtani, B. Visible-light-induced photocatalysis through surface plasmon excitation of gold on titania surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 2344–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Gaspera, E.; Bersani, M.; Mattei, G.; Nguyen, T.-L.; Mulvaney, P.; Martucci, A. Cooperative effect of Au and Pt inside TiO2 matrix for optical hydrogen detection at room temperature using surface plasmon spectroscopy. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 5972–5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, W.; Hung, W.H.; Pavaskar, P.; Goeppert, A.; Aykol, M.; Cronin, S.B. Photocatalytic conversion of CO2 to hydrocarbon fuels via plasmon-enhanced absorption and metallic interband transitions. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.K.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Tan, L.K.; Chiam, S.Y.; Tripathy, S.; Gao, H. Field effects in plasmonic photocatalyst by precise SiO2 thickness control using atomic layer deposition. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, A.; Kamat, P.V. Capture, store, and discharge. shuttling photogenerated electrons across TiO2–silver interface. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 7369–7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Polavarapu, L.; Gao, N.; Pan, Y.; Yuan, P.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Q.-H. TiO2 coated Au/Ag nanorods with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light irradiation. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 4236–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmetykó, Á.; Szániel, Á.; Tsakiroglou, C.; Dombi, A.; Hernádi, K. Enhanced photocatalytic H2 generation on noble metal modified TiO2 catalysts excited with visible light irradiation. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2016, 117, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Tiruvalam, R.; He, Q.; Dimitratos, N.; Kesavan, L.; Hammond, C.; Lopez-Sanchez, J.A.; Bechstein, R.; Kiely, C.J.; Hutchings, G.J.; et al. Promotion of phenol photodecomposition over TiO2 using Au, Pd, and Au–Pd nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 6284–6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francioso, L.; Presicce, D.S.; Siciliano, P.; Ficarella, A. Combustion conditions discrimination properties of Pt-doped TiO2 thin film oxygen sensor. Sens. Actuators B 2007, 123, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukoshi, Y.; Makise, Y.; Shuto, T.; Hu, J.; Tominaga, A.; Shironita, S.; Tanabe, S. Immobilization of noble metal nanoparticles on the surface of TiO2 by the sonochemical method: Photocatalytic production of hydrogen from an aqueous solution of ethanol. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007, 14, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; You, T.; Shi, W.; Li, J.; Guo, L. Au/TiO2/Au as a plasmonic coupling photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 6490–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, R.S.; Dongare, M.K. Sol-gel synthesis of Au/TiO2 thin films for photocatalytic degradation of phenol in sunlight. J. Mol. Catal. A 2006, 243, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarello, G.L.; Selli, E.; Forni, L. Photocatalytic hydrogen production over flame spray pyrolysis-synthesised TiO2 and Au/TiO2. Appl. Catal. B 2008, 84, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damato, T.C.; de Oliveira, C.C.S.; Ando, R.A.; Camargo, P.H.C. A facile approach to TiO2 colloidal spheres decorated with Au nanoparticles displaying well-defined sizes and uniform dispersion. Langmuir 2013, 29, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliev, V.; Tomova, D.; Bilyarska, L.; Tyuliev, G. Influence of the size of gold nanoparticles deposited on TiO2 upon the photocatalytic destruction of oxalic acid. J. Mol. Catal. A 2007, 263, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, S.; Shankar, M.V.; Palanichamy, M.; Arabindoo, B.; Bahnemann, D.W.; Murugesan, V. Enhancement of photocatalytic activity by metal deposition: Characterisation and photonic efficiency of Pt, Au and Pd deposited on TiO2 catalyst. Water Res. 2004, 38, 3001–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimling, J.; Maier, M.; Okenve, B.; Kotaidis, V.; Ballot, H.; Plech, A. Turkevich method for gold nanoparticle synthesis revisited. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 15700–15707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brust, M.; Walker, M.; Bethell, D.; Schiffrin, D.J.; Whyman, R. Synthesis of thiol-derivatised gold nanoparticles in a two-phase liquid-liquid system. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Zhu, J.; Cao, F.; Lu, Y.; Li, H. In situ encapsulation of Au nanoparticles in mesoporous core-shell TiO2 microspheres with enhanced activity and durability. Chem. Commun. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes Silva, C.; Juárez, R.; Marino, T.; Molinari, R.; García, H. Influence of excitation wavelength (UV or visible light) on the photocatalytic activity of titania containing gold nanoparticles for the generation of hydrogen or oxygen from water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, S.; Xu, Y.-J. Recent progress on metal core@semiconductor shell nanocomposites as a promising type of photocatalyst. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 2227–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petronella, F.; Fanizza, E.; Mascolo, G.; Locaputo, V.; Bertinetti, L.; Martra, G.; Coluccia, S.; Agostiano, A.; Curri, M.L.; Comparelli, R. Photocatalytic activity of nanocomposite catalyst films based on nanocrystalline metal/semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 12033–12040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, E.; Yoshiiri, K.; Wei, Z.; Zheng, S.; Kastl, E.; Remita, H.; Ohtani, B.; Rau, S. Hybrid photocatalysts composed of titania modified with plasmonic nanoparticles and ruthenium complexes for decomposition of organic compounds. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 178, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzoli, P.D.; Comparelli, R.; Fanizza, E.; Curri, M.L.; Agostiano, A.; Laub, D. Photocatalytic synthesis of silver nanoparticles stabilized by TiO2 nanorods: A semiconductor/metal nanocomposite in homogeneous nonpolar solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3868–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzoli, P.D.; Curri, M.L.; Giannini, C.; Agostiano, A. Synthesis of TiO2-Au composites by titania-nanorod-assisted generation of gold nanoparticles at aqueous/nonpolar interfaces. Small 2006, 2, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yang, S.; Hao, B.; Ruan, J.; Ma, P.-C. Preparation of fiber-based plasmonic photocatalyst and its photocatalytic performance under the visible light. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 166–167, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia, J.J.; Ávila-Martínez, E.G.; Rojas, H.; Navío, J.A.; Hidalgo, M.C. Study of the E. coli elimination from urban wastewater over photocatalysts based on metallized TiO2. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 200, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonsanti, R.; Grillo, V.; Carlino, E.; Giannini, C.; Curri, M.L.; Innocenti, C.; Sangregorio, C.; Achterhold, K.; Parak, F.G.; Agostiano, A.; et al. Seeded growth of asymmetric binary nanocrystals made of a semiconductor TiO2 rodlike section and a magnetic γ-Fe2O3 spherical domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 16953–16970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekeufack, D.D.; Brioude, A.; Mouti, A.; Alauzun, J.G.; Stadelmann, P.; Coleman, A.W.; Miele, P. Core-shell Au@(TiO2, SiO2) nanoparticles with tunable morphology. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4544–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastoriza-Santos, I.; Koktysh, D.S.; Mamedov, A.A.; Giersig, M.; Kotov, N.A.; Liz-Marzán, L.M. One-pot synthesis of Ag@TiO2 core–shell nanoparticles and their layer-by-layer assembly. Langmuir 2000, 16, 2731–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayya, K.S.; Gittins, D.I.; Caruso, F. Gold–titania core–shell nanoparticles by polyelectrolyte complexation with a titania precursor. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 3833–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, S.; Fu, X.; Xu, Y.-J. Synthesis of M@TiO2 (M = Au, Pd, Pt) core–shell nanocomposites with tunable photoreactivity. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2011, 115, 9136–9145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, Y.; Kanda, T.; Torigoe, K.; Sakai, H.; Abe, M. Preparation of gold/silver/titania trilayered nanorods and their photocatalytic activities. Langmuir 2014, 30, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Liu, D.; Mubeen, S.; Chuong, T.T.; Moskovits, M.; Stucky, G.D. Anisotropic growth of TiO2 onto gold nanorods for plasmon-enhanced hydrogen production from water reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1114–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, S.F.; Ye, W.; Guo, X.; Xu, X.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Yang, J. Gold nanorods coated by oxygen-deficient TiO2 as an advanced photocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 39144–39149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.C.; Wang, J. Metal nanocrystal-embedded hollow mesoporous TiO2 and ZrO2 microspheres prepared with polystyrene nanospheres as carriers and templates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoobakht, B.; El-Sayed, M.A. Preparation and growth mechanism of gold nanorods (NRs) using seed-mediated growth method. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 1957–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Meng, C.; Lin, L.; Peng, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Dai, W.; Fu, X. A heterostructured TiO2-C3N4 support for gold catalysts: A superior preferential oxidation of CO in the presence of H2 under visible light irradiation and without visible light irradiation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wu, S.; Xin, Y. Synthesis of Au–CuS–TiO2 nanobelts photocatalyst for efficient photocatalytic degradation of antibiotic oxytetracycline. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 302, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Wang, M.; Ran, C.; Yao, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; He, D.; Bai, J. One-pot synthesis of Ag/r-GO/TiO2 nanocomposites with high solar absorption and enhanced anti-recombination in photocatalytic applications. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 5498–5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hintsho, N.; Petrik, L.; Nechaev, A.; Titinchi, S.; Ndungu, P. Photo-catalytic activity of titanium dioxide carbon nanotube nano-composites modified with silver and palladium nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 156–157, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, F.; Dong, W.; Xu, L.; Wu, K.; Xu, G.; Chen, W. Recyclable silver-decorated magnetic titania nanocomposite with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 189, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, C.; Luo, S.; Xu, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, B. Magnetic TiO2-graphene composite as a high-performance and recyclable platform for efficient photocatalytic removal of herbicides from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 252–253, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.-W.; Gao, Z.-D.; Han, K.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.-Y. Synthesis of magnetically separable Ag3PO4/TiO2/Fe3O4 heterostructure with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light for photoinactivation of bacteria. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 15122–15131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Zhan, S.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, Q. Superior antibacterial activity of Fe3O4-TiO2 nanosheets under solar light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 21875–21883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, C.; Wei, J.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, R.; Pan, C.; Shi, J. Facile synthesis of PANI-modified CoFe2O4–TiO2 hierarchical flower-like nanoarchitectures with high photocatalytic activity. J. Nanopart. Res. 2013, 15, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, R.; Westwood, A. Carbonaceous nanomaterials for the enhancement of TiO2 photocatalysis. Carbon 2011, 49, 741–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woan, K.; Pyrgiotakis, G.; Sigmund, W. Photocatalytic carbon-nanotube–TiO2 composites. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2233–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.M.; Chai, S.-P.; Xu, B.-Q.; Mohamed, A.R. Enhanced visible light responsive MWCNT/TiO2 core–shell nanocomposites as the potential photocatalyst for reduction of CO2 into methane. Sol. Energy Mater. 2014, 122, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karousis, N.; Tagmatarchis, N.; Tasis, D. Current Progress on the chemical modification of carbon nanotubes. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5366–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, A.A.; Geioushy, R.A.; Bouzid, H.; Al-Sayari, S.A.; Al-Hajry, A.; Bahnemann, D.W. TiO2 decoration of graphene layers for highly efficient photocatalyst: Impact of calcination at different gas atmosphere on photocatalytic efficiency. Appl. Catal. B 2013, 129, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lv, T.; Zhu, Z. Template-assisted synthesis of hollow TiO2@rGO core–shell structural nanospheres with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Mol. Catal. A 2015, 404–405, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Tian, Q.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J. A general approach for the growth of metal oxide nanorod arrays on graphene sheets and their applications. Chem. A Eur. J. 2011, 17, 13912–13917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, W.; Yu, S.; Yan, X. Three dimensional carbogenic dots/TiO2 nanoheterojunctions with enhanced visible light-driven photocatalytic activity. Carbon 2014, 79, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, Z.; Meng, N.; McCarthy, D.T.; Deletic, A.; Pan, J.-H.; Zhang, X. Highly dispersed TiO2 nanocrystals and carbon dots on reduced graphene oxide: Ternary nanocomposites for accelerated photocatalytic water disinfection. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 202, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Yang, D.; Xiao, T.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, Z. Biomimetic fabrication of g-C3N4/TiO2 nanosheets with enhanced photocatalytic activity toward organic pollutant degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 260, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIRECTIVE 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health/endocrine_disruptors/docs/wfd_200060ec_directive_en.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- Oller, I.; Malato, S.; Sánchez-Pérez, J.A. Combination of advanced oxidation processes and biological treatments for wastewater decontamination—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4141–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, M.N.; Jin, B.; Chow, C.W.K.; Saint, C. Recent developments in photocatalytic water treatment technology: A review. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2997–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaya, U.I.; Abdullah, A.H. Heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants over titanium dioxide: A review of fundamentals, progress and problems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2008, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, A.; Ferro, G.; Alferez, M.C.; Polo-López, M.I.; Fernández-Ibañez, P.; Rizzo, L. Inactivation and regrowth of multidrug resistant bacteria in urban wastewater after disinfection by solar-driven and chlorination processes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 148, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malato, S.; Fernández-Ibáñez, P.; Maldonado, M.I.; Blanco, J.; Gernjak, W. Decontamination and disinfection of water by solar photocatalysis: Recent overview and trends. Catal. Today 2009, 147, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Feng, J.; Fan, M.; Pi, Y.; Hu, L.; Han, X.; Liu, M.; Sun, J.; Sun, J. Recent developments in heterogeneous photocatalytic water treatment using visible light-responsive photocatalysts: A review. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 14610–14630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, E.; Wei, Z.; Karabiyik, B.; Herissan, A.; Janczarek, M.; Endo, M.; Markowska-Szczupak, A.; Remita, H.; Ohtani, B. Silver-modified titania with enhanced photocatalytic and antimicrobial properties under UV and visible light irradiation. Catal. Today 2015, 252, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Gan, W.; Xiao, S.; Zhan, X.; Li, J. A robust superhydrophobic antibacterial Ag–TiO2 composite film immobilized on wood substrate for photodegradation of phenol under visible-light illumination. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 2170–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S.; Khadem, E. Carbon nanotube–metal oxide nanocomposites: Fabrication, properties and applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 302, 344–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dai, J.; Li, J. Visible-light-induced photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI) with coupled Bi2O3/TiO2 photocatalyst and the synergistic bisphenol A oxidation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 2435–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Luo, C.; Xiong, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Gu, H. Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) decorated TiO2 microspheres for visible-light photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI). J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 690, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Yang, W.; Cao, J.; Li, Q.; Peng, Y.; Shang, J.K. Anti-algal activity of palladium oxide-modified nitrogen-doped titanium oxide photocatalyst on Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 and its photocatalytic degradation on Microcystin LR under visible light illumination. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 264, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ang, H.M.; Tade, M.O. Volatile organic compounds in indoor environment and photocatalytic oxidation: State of the art. Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasek, J.; Yu, Y.-H.; Wu, J.C.S. Removal of NOx by photocatalytic processes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2013, 14, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbuena, J.; Carraro, G.; Cruz, M.; Gasparotto, A.; Maccato, C.; Pastor, A.; Sada, C.; Barreca, D.; Sanchez, L. Advances in photocatalytic NOx abatement through the use of Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 74878–74885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapalis, A.; Todorova, N.; Giannakopoulou, T.; Boukos, N.; Speliotis, T.; Dimotikali, D.; Yu, J. TiO2/graphene composite photocatalysts for NOx removal: A comparison of surfactant-stabilized graphene and reduced graphene oxide. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 180, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, C.; He, H. Enhanced photocatalytic oxidation of NO over g-C3N4-TiO2 under UV and visible light. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 184, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Geng, J.; Jing, D. Photodecomposition of NOx on Ag/TiO2 composite catalysts in a gas phase reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 307, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeestere, K.; Dewulf, J.; Ohno, T.; Salgado, P.H.; van Langenhove, H. Visible light mediated photocatalytic degradation of gaseous trichloroethylene and dimethyl sulfide on modified titanium dioxide. Appl. Catal. B 2005, 61, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, D.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, W.; Shao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sun, M.; Fu, X. Efficient degradation of benzene over LaVO4/TiO2 nanocrystalline heterojunction photocatalyst under visible light irradiation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4164–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, G.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Fu, X. InVO4-sensitized TiO2 photocatalysts for efficient air purification with visible light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2008, 193, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratova, M.; Kelly, P.J.; West, G.T.; Tosheva, L.; Edge, M. Reactive magnetron sputtering deposition of bismuth tungstate onto titania nanoparticles for enhancing visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 392, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongaree, M.; Chiarakorn, S.; Chuangchote, S.; Sagawa, T. Photocatalytic performance of electrospun CNT/TiO2 nanofibers in a simulated air purifier under visible light irradiation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 21395–21406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stucchi, M.; Bianchi, C.L.; Pirola, C.; Cerrato, G.; Morandi, S.; Argirusis, C.; Sourkouni, G.; Naldoni, A.; Capucci, V. Copper NPs decorated titania: A novel synthesis by high energy US with a study of the photocatalytic activity under visible light. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 31, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stucchi, M.; Bianchi, C.L.; Pirola, C.; Vitali, S.; Cerrato, G.; Morandi, S.; Argirusis, C.; Sourkouni, G.; Sakkas, P.M.; Capucci, V. Surface decoration of commercial micro-sized TiO2 by means of high energy ultrasound: A way to enhance its photocatalytic activity under visible light. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 178, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragesh, P.; Anand Ganesh, V.; Nair, S.V.; Nair, A.S. A review on ‘self-cleaning and multifunctional materials’. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 14773–14797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhai, R.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, W.; Wang, R.; Pan, K.; Tian, C.; Fu, H. Hierarchical flake-like Bi2MoO6/TiO2 bilayer films for visible-light-induced self-cleaning applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 6961–6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Pillai, S.C. Self-cleaning applications of TiO2 by photo-induced hydrophilicity and photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 176–177, 396–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.F.; Yu, C.F.; Ni, C.Y. Low temperature synthesis and photocatalytic performance of tungsten trioxide film. Surf. Eng. 2016, 32, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Miyauchi, M.; Sunada, K.; Minoshima, M.; Liu, M.; Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Shimodaira, Y.; Hosogi, Y.; Kuroda, Y. Hybrid CuxO/TiO2 nanocomposites as risk-reduction materials in indoor environments. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbruggen, S.W.; Keulemans, M.; Filippousi, M.; Flahaut, D.; van Tendeloo, G.; Lacombe, S.; Martens, J.A.; Lenaerts, S. Plasmonic gold–silver alloy on TiO2 photocatalysts with tunable visible light activity. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 156–157, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Zheng, L.; Tan, B.; Shu, H. Photocatalytic self-cleaning cotton fabrics with platinum(IV) chloride modified TiO2 and N-TiO2 coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 386, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Xin, J.H. Advanced visible-light-driven self-cleaning cotton by Au/TiO2/SiO2 photocatalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, E.; Daoud, W.A.; Sun, L.; Wang, X. Visible and UV functionality of TiO2 ternary nanocomposites on cotton. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 321, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronella, F.; Rtimi, S.; Comparelli, R.; Sanjines, R.; Pulgarin, C.; Curri, M.L.; Kiwi, J. Uniform TiO2/In2O3 surface films effective in bacterial inactivation under visible light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2014, 279, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Yazdanshenas, M.E.; Khajavi, R.; Rashidi, A.; Mirjalili, M. Using graphene/TiO2 nanocomposite as a new route for preparation of electroconductive, self-cleaning, antibacterial and antifungal cotton fabric without toxicity. Cellulose 2014, 21, 3813–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Su, S.-K.; Chang, C.-J.; Huang, C.-H.; Chen, J.-K. Sol-gel-synthesized titania-vanadia nanocrystal films for triple-functional window coatings. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 17610–17619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mahendra, S.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Nanomaterials in the construction industry: A review of their applications and environmental health and safety considerations. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3580–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzmiller, M.; Mahendra, S.; Damoiseaux, R. Nanotechnology in Eco-Efficient Construction; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2013; pp. 127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Torgal, F.P.; Jalali, S. Nanotechnology: Advantages and drawbacks in the field of construction and building materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macphee, D.E.; Folli, A. Photocatalytic concretes—The interface between photocatalysis and cement chemistry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 85, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Poon, C.-S. Photocatalytic construction and building materials: From fundamentals to applications. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1899–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, E.; Fregni, A.; Gabrielli, R.; Graziani, G.; Sassoni, E. Compatibility of photocatalytic TiO2-based finishing for renders in architectural restoration: A preliminary study. Build. Environ. 2014, 80, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamonti, L.; Alfieri, I.; Franzò, M.; Lorenzi, A.; Montenero, A.; Predieri, G.; Raganato, M.; Calia, A.; Lazzarini, L.; Bersani, D.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of nanocrystalline TiO2 with application as photoactive coating on stones. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 13264–13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, L.; Rojas, M.; Mosquera, M.J. Ag–SiO2–TiO2 nanocomposite coatings with enhanced photoactivity for self-cleaning application on building materials. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 178, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.-Z.; Maury-Ramirez, A.; Poon, C.S. Photocatalytic activities of titanium dioxide incorporated architectural mortars: Effects of weathering and activation light. Build. Environ. 2015, 94, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, M.; Zatorska, J.; Czyżewski, A.; Bubacz, K.; Kusiak-Nejman, E.; Morawski, A.W. Self-cleaning properties of cement plates loaded with N,C-modified TiO2 photocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 330, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Truppi, A.; Petronella, F.; Placido, T.; Striccoli, M.; Agostiano, A.; Curri, M.L.; Comparelli, R. Visible-Light-Active TiO2-Based Hybrid Nanocatalysts for Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2017, 7, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7040100

Truppi A, Petronella F, Placido T, Striccoli M, Agostiano A, Curri ML, Comparelli R. Visible-Light-Active TiO2-Based Hybrid Nanocatalysts for Environmental Applications. Catalysts. 2017; 7(4):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7040100

Chicago/Turabian StyleTruppi, Alessandra, Francesca Petronella, Tiziana Placido, Marinella Striccoli, Angela Agostiano, Maria Lucia Curri, and Roberto Comparelli. 2017. "Visible-Light-Active TiO2-Based Hybrid Nanocatalysts for Environmental Applications" Catalysts 7, no. 4: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal7040100