Interdependences between Smallholder Farming and Environmental Management in Rural Malawi: A Case of Agriculture-Induced Environmental Degradation in Malingunde Extension Planning Area (EPA)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

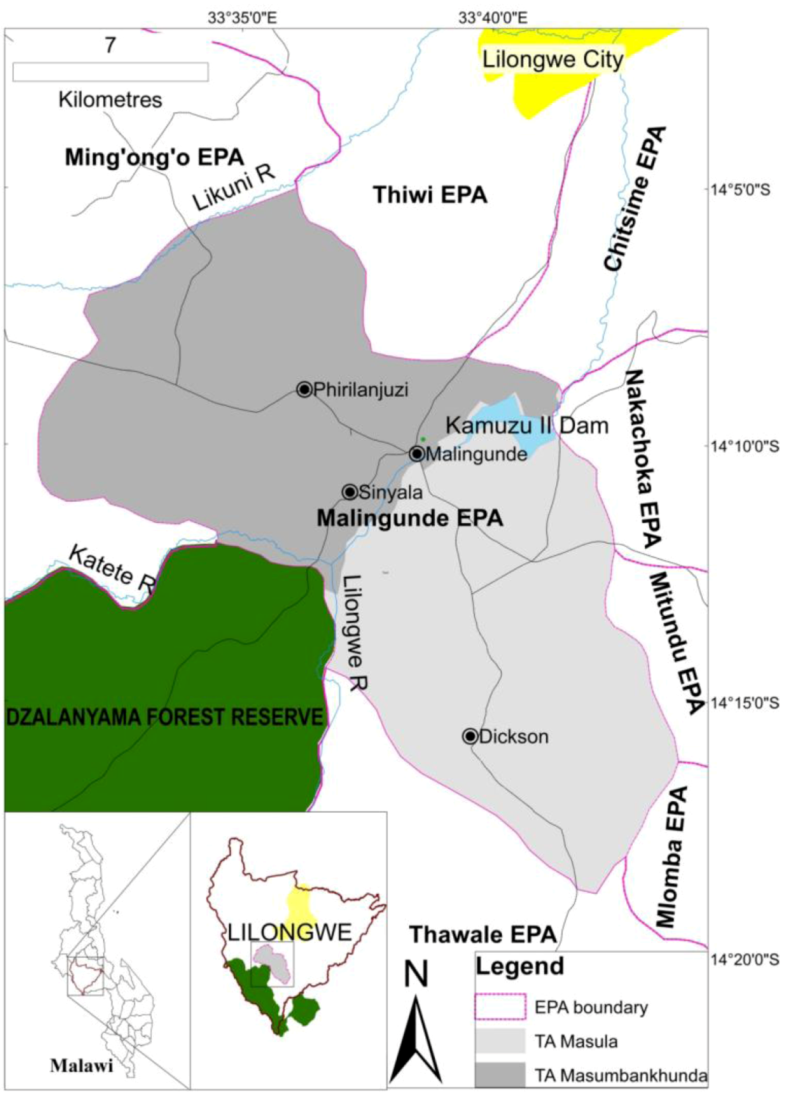

2.1. Study Area

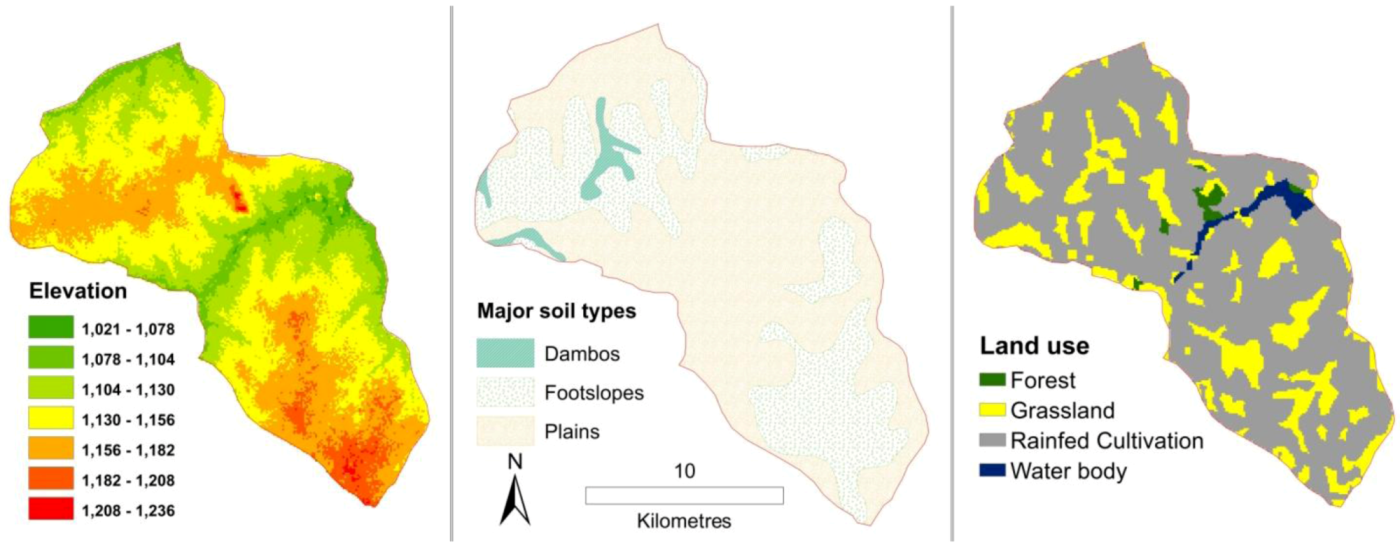

2.2. Administrative Structure

| EPA | Total Farm Families | Total Smallholder Arable Land (ha) | Average Land Holding Size (ha) | Sections | Extension Workers* | Extension Services Ratio** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malingunde | 18,282 | 19,667 | 1.08 | 12 | 9 (24) | 1:2031 (1:761) |

| Thawale | 18,665 | 25,000 | 1.34 | 8 | 5 (16) | 1:3733 (1:1167) |

| Ming’ong’o | 22,667 | 30,766 | 1.36 | 15 | 12 (30) | 1:1889 (1:756) |

3. Smallholder Farming in Malawi

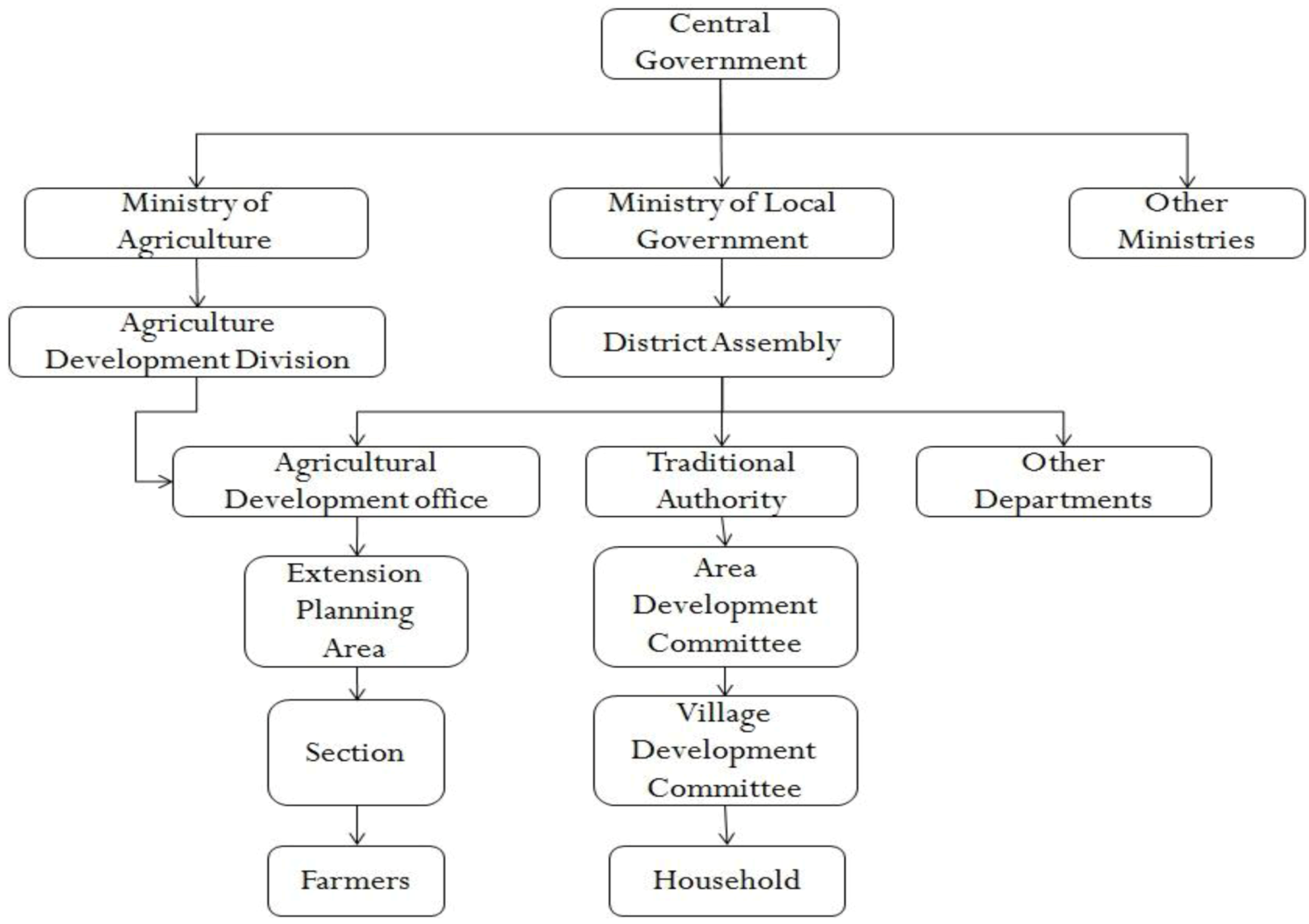

3.1. Household Characteristics

| Household Characteristic | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size (including children) | 1 | 12 | 4.39 | 1.72 |

| Children less than 15 years | 0 | 9 | 2.12 | 1.36 |

| Children older than 15 | 0 | 8 | 0.49 | 0.89 |

| Total arable land | 0.20 | 7.69 | 0.97 | 0.55 |

| Land allocated to maize | 0.00 | 4.45 | 0.59 | 0.32 |

| Land allocated to groundnuts | 0.00 | 2.43 | 0.32 | 0.25 |

| Land allocated to tobacco | 0.00 | 1.21 | 0.015 | 0.08 |

| Land allocated to soybeans | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.022 | 0.07 |

| Land allocated to cassava | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.002 | 0.02 |

| Land allocated to sweet potatoes | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.020 | 0.072 |

| Land allocated to other crops | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.003 | 0.024 |

3.2. Smallholder Farming Challenges

3.2.1. Labor

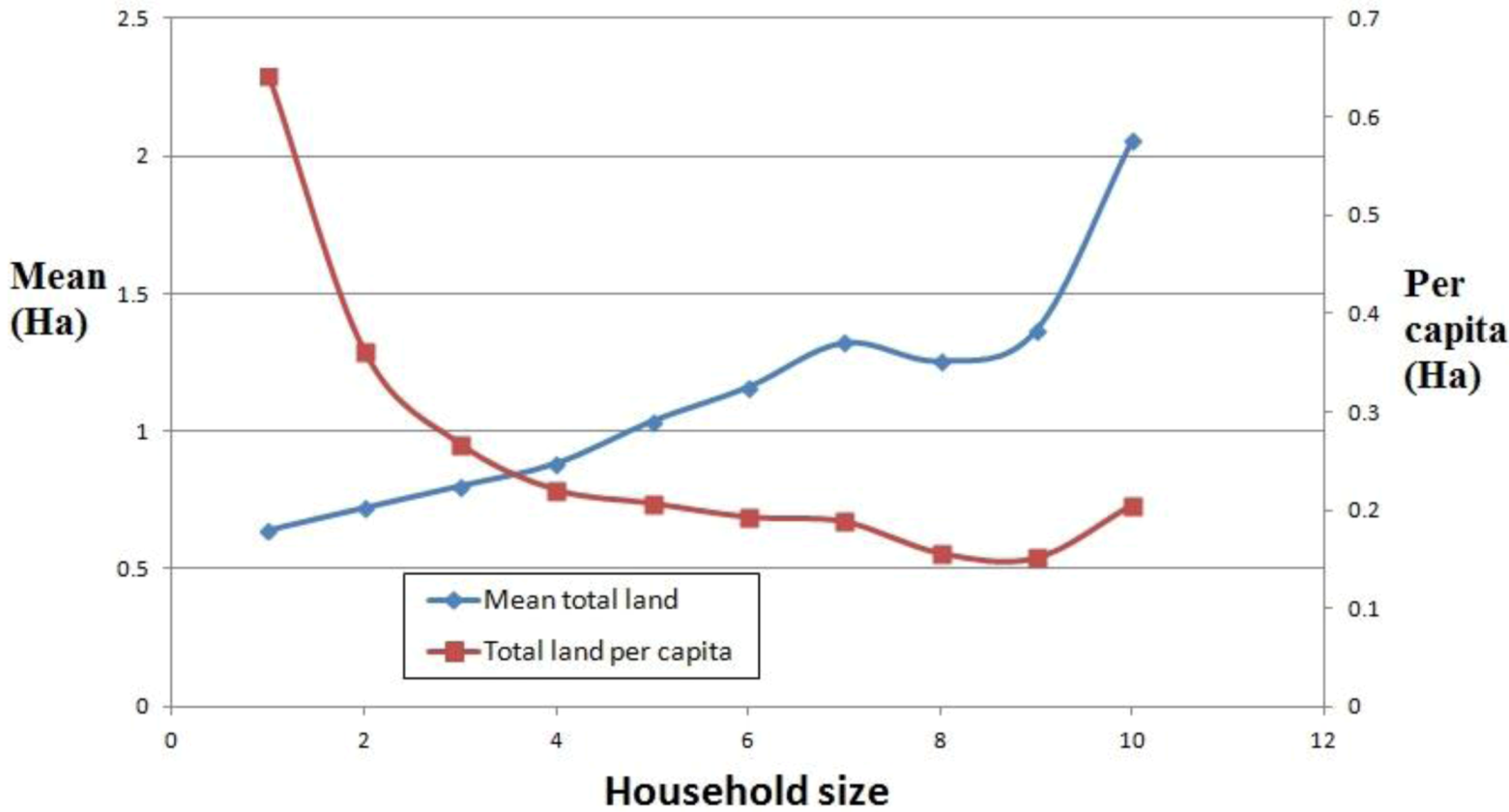

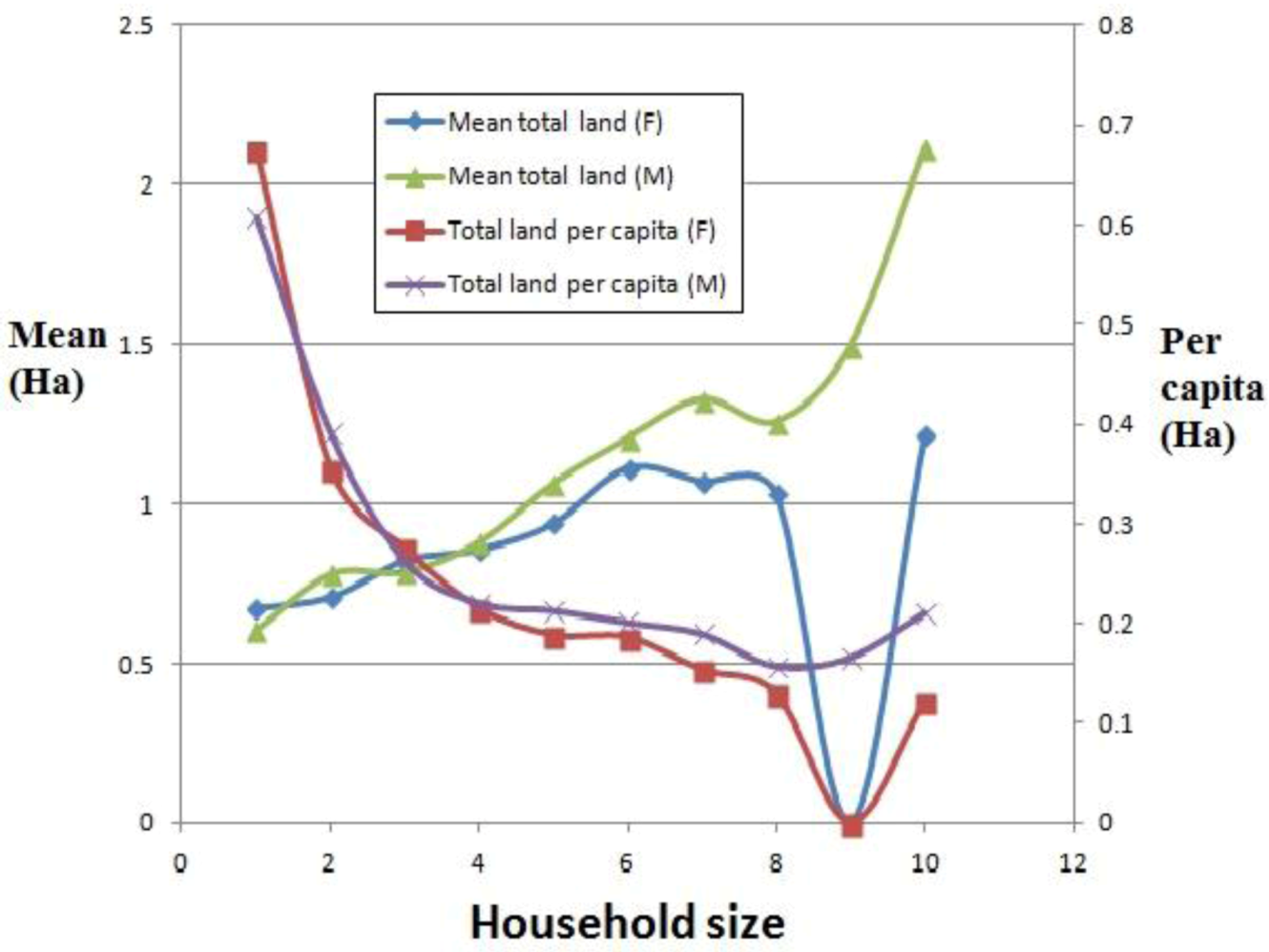

3.2.2. Land

3.2.3. Other Factors

4. Environmental Land Use Management

Charcoal Production

The Charcoal Value Chain

Charcoal-Making Process

- zero or low investment;

- use of construction materials, which are at hand on the site or available nearby, e.g., clay, soft-burnt bricks;

- zero or low maintenance costs achieved by avoiding metal parts in the kiln construction as much as possible;

- manpower not being a major concern; normal raw materials consisting largely of wood logs (other types of biomass may be carbonized also);

- by-product recovery being limited, owing to the fact that no sophisticated equipment is employed; and

- typically being a family or cooperative initiative.

Competition for Labor

Controlling Charcoal Production

5. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgements

References

- Chirwa, E.W.; Matita, M. From Subsistence to Smallholder Commercial Farming in Malawi: A Case of NASFAM Commercialisation Initiative. Available online: http://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/123456789/2268 (accessed on 7 September 2012).

- Governement of Malawi and The World bank, Malawi Poverty and Vulnerability Assessment: Investing in Our Future; Ministry of Economic Planning and Development/The World Bank: Lilongwe, Malawi/Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Environmental and Socio-Economic Baseline Study—Malawi; Norwegian Agency for Development Corporation (Norad): Oslo, Norway, 2009.

- Kaimowitz, D.; Angelsen, A. Economic Models of Tropical Deforestation. A Review; Centre for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tchale, H. The Efficiency of Smallholder Agriculture in Malawi; World Bank: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson, D.F. Ganyu casual labour, famine and HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi: Causality and casualty. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2006, 44, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Malawi, Lilongwe District Socio-Economic Profile; Lilongwe District Assembly: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2006.

- Malawi Country Economic Memorandum: Policies for Accelerating Growth; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Food and Agriculture Organization/World Food Program. Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission to Malawi. Available online: http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp036450.htm (accessed 10 August 2012).

- Statistical Yearbook 2002; National Statistical Office, Government of Malawi: Zomba, Malawi, 2002.

- Mvula, P.M.; Chirwa, E.W.; Kadzandira, J. Poverty and Social Impact Assessment in Malawi: Closure of ADMARC Markets; Wadonda Consult & World Bank: Zomba, Malawi, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, P. Rural income and poverty in a time of radical change in Malawi. J. Dev. Stud. 2006, 42, 322–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Office, Republic of Malawi 2008 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Report; Government of Malawi: Zomba, Malawi, 2008.

- Takane, T. Labour use in smallholder agriculture in Malawi: Six village case studies. Afr. Study Monogr. 2008, 29, 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Oversees Development Institute. Available online: http://www.odi.org.uk/ (accessed on 17 August 2012).

- Edriss, A.; Tchale, H.; Wobst, P. The Impact of Labour Market Liberalization on Maize Productivity and Rural Poverty in Malawi; Robert Bosch Foundation, Policy Analysis for Sustainable Agricultural Development (PASAD) Project-University of Bonn: Bonn, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside, M. When the Whole Is More Than the Sum of the Parts: the Effect of Cross-Border Interactions on Livelihood Security in Southern Malawi and Northern Mozambique. 1998. Available online: http://www.eldis.org/assets/Docs/27437.html#.URjo4h1JPpU (accessed on 17 August 2012).

- Chipande, G.H.R. Innovation adoption among female-headed households: The case of Malawi. Dev. Change 1987, 18, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Country Environmental Profile for Malawi; AGRIFOR Consult: Les Isnes, Belgium, 2006.

- Chinsinga, B. Exploring the Politics of Land Reforms in Malawi: A Case Study of the Community Based Rural Land Development Programme (CBRLDP); University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2008; Available online: http://www.ippg.org.uk/papers/dp20.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2013).

- Alwang, J.; Siegel, P.B. Labour shortages on small landholdings in Malawi: Implications for policy reforms. World Dev. 1999, 27, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, A.M.; BenYishay, A.; Beaman, L.; Fatch, P.; Magruder, J. Using Social Networks to Improve Agricultural Extension Services; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.mcc.gov/documents/Mobarak_Malawi_MCC.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2012).

- Levy, S.; Barahona, C.; Chinsinga, B. Food security, social protection, growth and poverty reduction synergies: The starter pack programme in Malawi. Nat. Resour. Perspect. 2004, 95, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kambewa, P.S.; Mataya, B.F.; Sichinga, W.K.; Johnson, T.R. Charcoal: The Reality—A Study of Charcoal Consumption, Trade and Production in Malawi. In Small and Medium Forestry Enterprise Series No. 21; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office, Malawi Population Census; Government of Malawi: Zomba, Malawi, 1998.

- Pennise, D.M.; Smith, K.R.; Kithinji, J.P.; Rezende, M.E.; Raad, T.J.; Zhang, J.; Chengwei, F. Emissions of greenhouse gases and other airborne pollutants from charcoal making in Kenya and Brazil. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 24143–24155. [Google Scholar]

- Emrich, W. Handbook of Charcoal Making: The Traditional and Industrial Methods; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Munthali, K.G. Modelling Deforestation in Dzalanyama Forest Reserve, Lilongwe, Malawi: Using Multi-Agent Simulation Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Munthali, K.G.; Murayama, Y. Interdependences between Smallholder Farming and Environmental Management in Rural Malawi: A Case of Agriculture-Induced Environmental Degradation in Malingunde Extension Planning Area (EPA). Land 2013, 2, 158-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/land2020158

Munthali KG, Murayama Y. Interdependences between Smallholder Farming and Environmental Management in Rural Malawi: A Case of Agriculture-Induced Environmental Degradation in Malingunde Extension Planning Area (EPA). Land. 2013; 2(2):158-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/land2020158

Chicago/Turabian StyleMunthali, Kondwani G., and Yuji Murayama. 2013. "Interdependences between Smallholder Farming and Environmental Management in Rural Malawi: A Case of Agriculture-Induced Environmental Degradation in Malingunde Extension Planning Area (EPA)" Land 2, no. 2: 158-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/land2020158

APA StyleMunthali, K. G., & Murayama, Y. (2013). Interdependences between Smallholder Farming and Environmental Management in Rural Malawi: A Case of Agriculture-Induced Environmental Degradation in Malingunde Extension Planning Area (EPA). Land, 2(2), 158-175. https://doi.org/10.3390/land2020158