1. Introduction

Landscape archaeology is currently hugely popular. However, there are problems with defining the term ‘landscape’. This is partially because the term is used in various ways, not only between different disciplines but also within each discipline, which forces us briefly to analyze the concept in an archaeological context. It should be acknowledged that the term has also been used very freely in archaeological writings. Many scholars have used the term as a ‘fashionable gloss’ for survey studies or an improved ‘site-catchment analysis’ [

1,

2]. One should, however, try to understand the term in its broader sense.

The concept of landscapes encompasses temporality, spatiality and materiality; therefore, much can be said about human responses to the changing conditions of life over time through its study. The term is concerned both with the conscious and the unconscious shaping of the land and the processes of organizing space, and involves interaction between the physical environment and human presence. As Matthew Johnson notes, “the two senses of the term ‘land-scape’ are important here: not just the land, but how it is viewed or mentally constructed” [

3].

Contemporary approaches to landscape archaeology include a broad range of archaeological issues, such as social organization, rural economy and sacred space, trying to extract agency, ideology, meaning, memory, identity, social order, morality and social transformation from landscapes. While the last decades of landscape archaeological research in the Eastern Mediterranean (and in the Mediterranean region in general) have seen an intensification of interest in bringing together geographic (concrete and descriptive forms concerned with determining the nature of and classifying places, as well as establishing the links between them) and sociological ‘imaginations’ (an aspiration to explain human behavior and activities in terms of social process abstractly constructed) [

4], some archaeologists have seen landscape as “the arena in which and through which memory, identity, social order and transformation are constructed, played out, re-invented, and changed” [

5]. Landscape then, can be seen as the ‘arena’ for social agency [

6].

Cypriot sacred landscapes are rarely examined in relation to political power, political economy and ideology. Such landscape perspectives are absent from studies of the crucial transitions from the Cypro–Archaic and Cypro–Classical city-kingdoms to the Hellenistic period, from the Hellenistic to the Roman era, and from Roman times to early Christianity. Acknowledging the potential of landscape studies to provide a major source of new interpretations on the

longue durée (the long-term approach to the study of the past, employed by the French

Annales School of history) this contribution should be regarded as a dynamic attempt to re-work and re-experience not only the Cypriot sacred landscapes through various transitional phases, but also to further illuminate the political and socio-cultural histories of the Cypriot city-kingdoms, the Hellenistic, the Roman and the Late Antique periods when viewed independently (

Figure 1). We demonstrate how a diachronic approach to Cypriot sacred landscapes, which includes ancient sanctuaries and early Christian basilicas can open new interpretative windows, impossible to reach without such a comparative approach. Late Antiquity, in particular, is a crucial period in the development of Cypriot sacred landscapes as again, similarly to the beginning of the Archaic period and the consolidation of the Iron Age polities, we move from a ‘half-empty’ to a ‘half-full’ and later to a ‘full’ sacred landscape.

2. Trends in Landscape Archaeology and Sacred Landscapes

Landscape archaeology has followed the main trends of the theoretical developments of archaeology by moving through a number of stages, though they have not been sequential. Recognizing the risk of oversimplification, Tony Wilkinson defined three broad strands of landscape archaeology. Firstly, the ‘cultural-historical’ approach (or the school of landscape history) draws on historical documents, archaeology and the landscape itself; secondly, ‘processual’ approaches embody a more ‘scientific’ methodology and include archaeological surveys, off-site and quantitative studies, catchment analysis, settlement archaeology and various ecosystem approaches; finally, ‘post-processual’ approaches are a reaction to the processual approach, and include phenomenological, ideational and symbolic/religious landscapes [

7].

Scientific or functional approaches, under the strand of ‘processual’ archaeology, have usually predominated, inferring social and economic dimensions of a range of spatial frames and statistical models [

8]. However, it was felt that the land remained a neutral and passive object, used by people, but otherwise relatively detached from them [

8]. Considering all the different approaches to the study of past landscapes, it should constantly be kept in mind that places and landscapes have been formed by the very act of living. The human factor and involvement, therefore, are key concepts that should not be underestimated or overlooked. Moreover, human activity and landscapes’ structure and temporality are vital issues, directly associated with the concept and perception of landscape [

9]. Already by the 1970s, ‘post-processual’ and ‘post-positivistic’ philosophies, humanistic concerns and calls for social relevance, built from existentialism, structuration, Marxist thought, feminism, idealism, phenomenology, and interactionism, were recast “as matched participants in [a] perpetual dialectic of mutual constitution” [

8]. Today the most prominent notions of landscape archaeology emphasize its socio-symbolic dimensions: “landscape is an entity that exists by virtue of its being perceived, experienced, and contextualized by people” [

5]. Landscape is never inert; people are directly associated with it, re-work it, appropriate it and contest it [

10]. In addition, the theory has moved on considerably to include ‘ecological’ and ‘co-production’ approaches in a more holistic way [

11,

12].

Landscape archaeology, therefore, has the potential to be truly unifying, bridging the gap between scientific or positivistic archaeologies and those that approach it from the perspective of social theory or the humanities [

13]. There is undoubtedly a need for an integrated approach in which all the approaches mentioned above are taken into account. Such a holistic approach and interpretation, which regards landscape as a reflection of society and as an expression of a system of cultural meaning, and which seeks to read the materialization of ideologies on land and monuments, is currently applied to the reading of Cypriot sacred landscapes as part of the Research Network’s ‘Unlocking Sacred Landscapes’ (UnSaLa) project and the archaeological project ‘Settled and Sacred Landscapes of Cyprus’ (SeSaLaC).

The term ‘sacred landscapes’ has been chosen in acknowledgement of the inspiration provided by Susan Alcock’s work; by using this term in her examination of the Hellenistic and Roman sacred landscapes of the Greek world, Alcock shows that the relationship between religion, politics, identity and memory was more intimate and more involved than has often been assumed [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. She regards sacred landscapes emerging:

“…as both culturally constructed and historically sensitive, immensely variable through time and space. Far from being immune to developments in other aspects of human life, they can reflect a very wide cultural and political milieu. Yet they also provide more than a simple mirror of change by their active participation in the conditions of social reproduction”.

The investigation of ‘ideational’ or ‘associative’ landscapes, where people associate features in the natural and built landscapes with their own memories, meanings or emotions [

5,

16], is particularly relevant to sacred landscapes [

6]. ‘Ideational’, as Bernard Knapp and Wendy Ashmore argue, is far less linked to an articulated system than the terms ‘ideology’ or ‘ideological’; therefore, it can also be used to embrace sacred as well as other kinds of meanings attached to and embodied in landscapes [

5].

The concept of memory is crucial in the process of socializing landscape and naturalizing cultural features in the land. It is created by the repeated movement of the body throughout the landscape. Barbara Bender regards landscape as a process that is “intensely political, a way of perceiving, experiencing, and remembering the world” [

10]; landscapes not only shape but are shaped by human experience [

8]. Christopher Tilley’s influential study is concerned explicitly with phenomenology of landscape as an experience [

19]. The experience is ‘synesthetic’, “both creating and engaging a narrative linking the body—individual and social group—with the land” [

8]. The movement of the body through space is crucial, and as it provides people with a particular way of viewing the world, it has important implications for the maintenance of power relations [

19,

20]. By controlling the way people move through space, it is possible to reproduce dominant perspectives on the world [

19]. Robert Johnston sees landscape as existing through two different understandings of ‘perception’: in the first, perception acts as a filter on the real world; in the second, it is a process through which people understand the world [

21]. In studying landscapes, perception cannot be ignored and it should be acknowledged that perception is not beyond archaeological analysis [

2].

Questions about ascribing meaning to landscapes and issues of social mechanisms by which meaning is attached, as well as the range of meanings that can be encompassed should be raised [

8]. Meaning is usually attached through memory and ritual. However, memories and meanings are created afresh from generation to generation and differ between individuals. As Ashmore notes, “prominent among the meanings of landscape are power and identity, variously defined and expressed in sundry forms” [

8]. As landscape delineates memory and declares identity, the land itself plays a fundamental role in the social and cultural order and in human relations. Further, “as a community merges with its habitus through the actions and activities of its members, the landscape may become a key reference point for expressions of individual as well as group identity” [

5]. The transformation of landscapes has been associated with the transformation of the social order, coming from short-term events (socio-political time) or medium-term cycles (socio-economic time). As Knapp and Ashmore note, since landscapes embody multiple times as well as multiple places, they consequently materialize not only continuity but also change and transformation [

5]. Landscapes are perpetually under construction, which is why an enduring theme in recent archaeological thought has been the reading of social power from those modified landscapes [

22].

John Cherry has emphasized the need to bring into a closer dialogue the various approaches of landscape archaeology [

23]. Survey reports should be combined with excavation reports, political history and notions of recent ‘archaeologies of landscape’ [

5]. Emphasis should be given to “the process of re-interpretation and re-working of dynamic landscapes whose changing appearance communicates cultural values and is charged with meaning” [

23]. The study of Cypriot sacred landscapes, therefore, may become a significant interlocutor, which stimulates the understanding of the broader political, economic, and cultural space.

3. Cypriot Sacred Landscapes of Ancient Cyprus (Archaic-Roman Times)

The study of Cypriot sacred landscapes within the

longue durée, their transformations and their possible change of meanings, reinforce current interpretations suggesting that the extra-urban sanctuaries played an important role in the political setting of the city-kingdoms, which transformed over time. Moving from the period of many independent

basileis to the island-wide rule of the

strategos, it has been discussed how Hellenistic ‘urbanization’, settlement patterns, social memory and politico-religious ideology present a picture of a more unified socio-political sacred space. As shown in

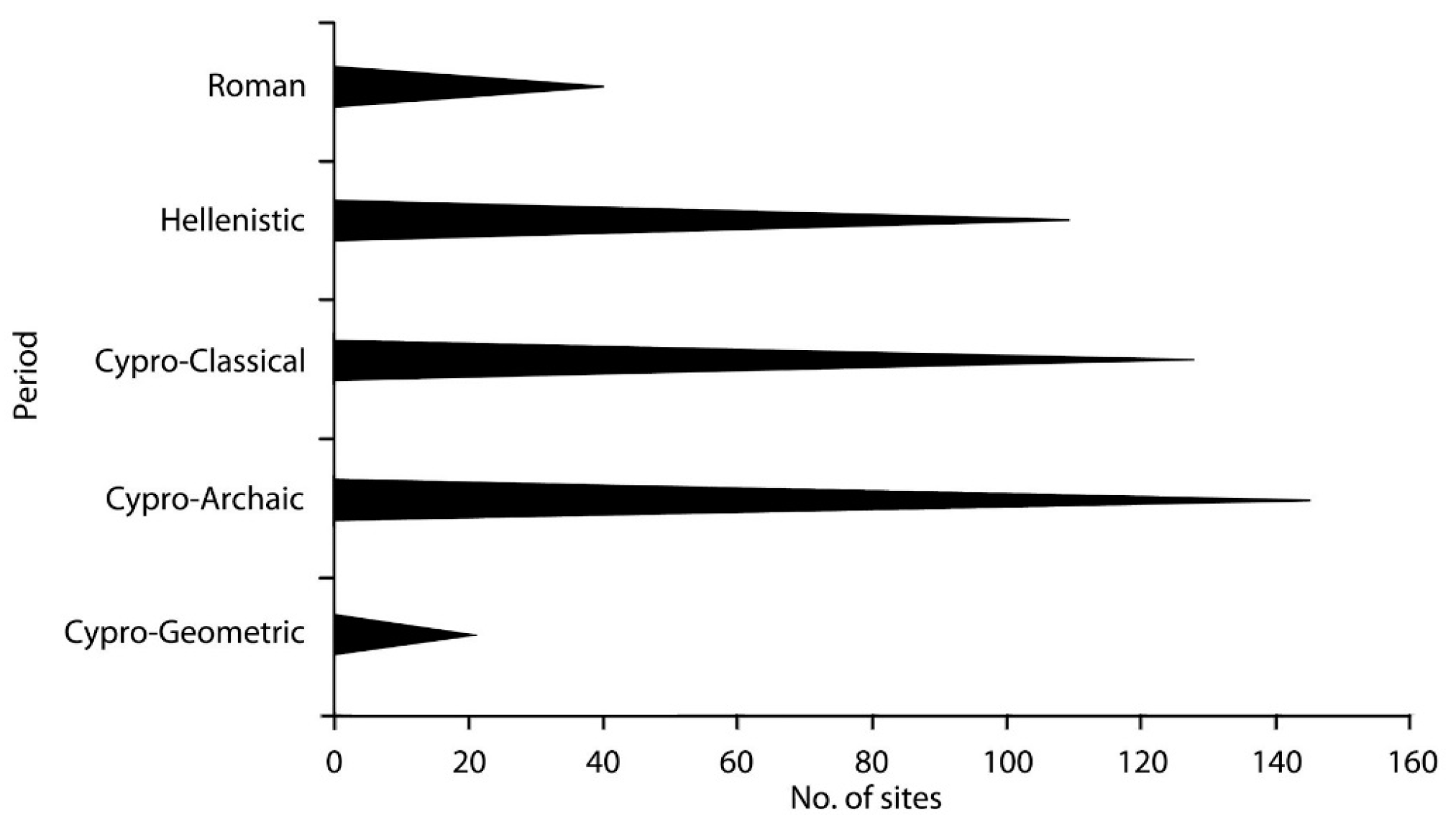

Figure 2, by the Roman period many Cypriot extra-urban sanctuaries were deserted and only a few of them remodeled and enlarged. If we are going to understand this phenomenon, we have to move well beyond the Roman period (before and after) in order to insert the development of Cypriot sacred landscapes within their individual and contextual insular development.

Old excavation of extra-urban shrines of the Archaic and Classical periods has produced evidence that has also been confirmed by recent systematic excavation activity [

24], and which highlights the role of the Cypriot Iron Age sanctuary as a focus of wealth disposal and economic control in the community [

25,

26]. There was evidence of the segmentation of space, consumption of food and drink, industrial activities, large-scale storage and display, and the disposal of votive images related to royal ideology. While urban sanctuaries become religious communal centers, where social, cultural and political identities are affirmed, an indication of the probable use of extra-urban sacred space in the political setting of the various city-kingdoms has usually been observed [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

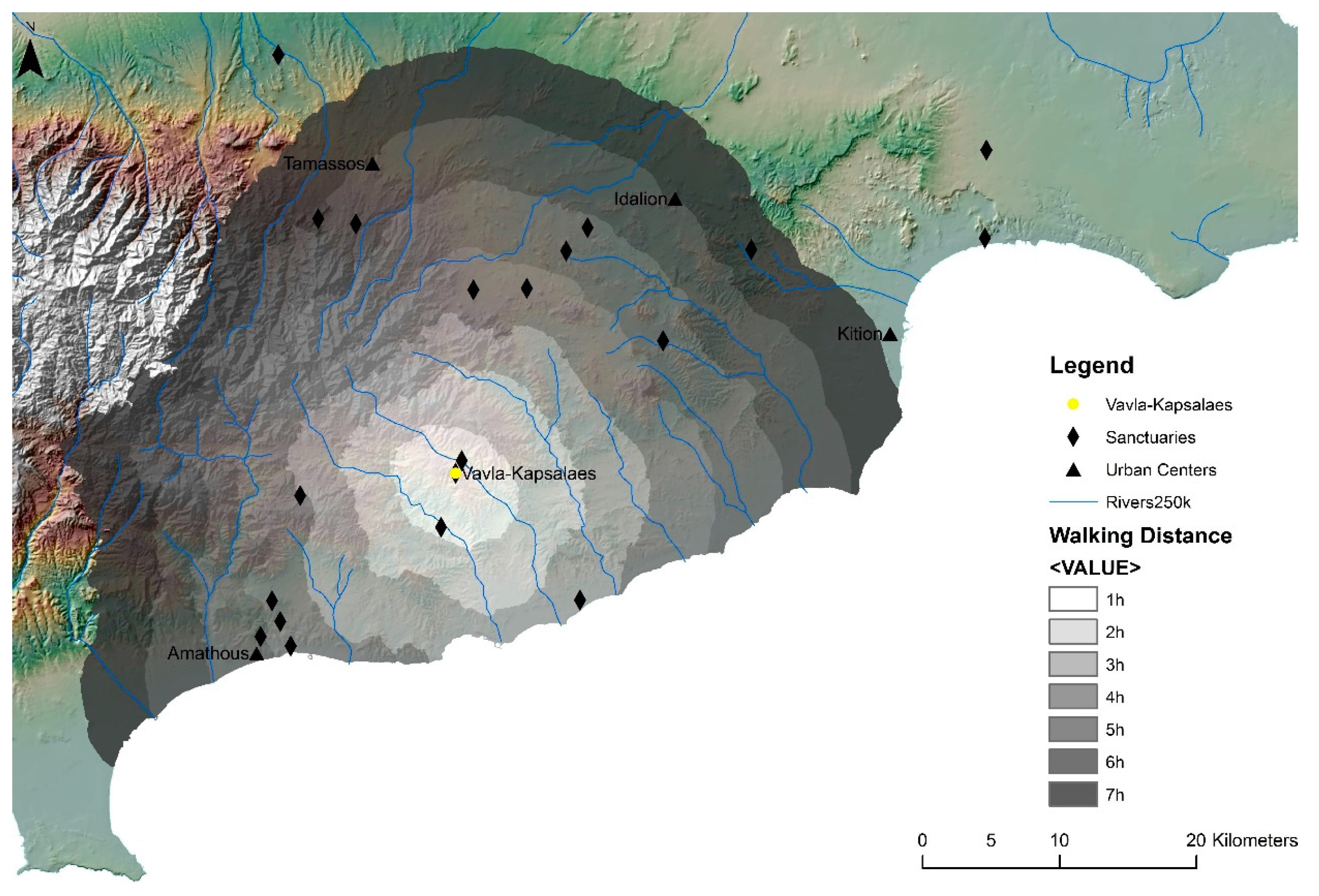

42]. One of the present authors has argued in print on several occasions that the distribution of these sanctuaries across the landscape served as a map for a socio-political system, which provided a mechanism for the centralized Archaic and Classical city-kingdom authorities to organize and control their peripheries. Environmental and Geographic Information System (GIS) analyses that were employed for the first time in the history of research on Cypriot sacred landscapes by UnSaLa and SeSaLaC, reinforced this argument about the territoriality of Iron Age Cypriot sanctuaries. Next to other archaeological evidence and GIS analyses that support the relation of the Vavla-Kapsales sanctuary with the polity of Amathous, for example, the results of Cost Surface Analysis, which calculates the walking distance between places, also strengthened this interpretation (

Figure 3) [

41].

The transformation of Hellenistic political topographies, and the passing of Cyprus from segmented to unitary, colonial administration under a foreign general (the

strategos) brought a marked urban and extra-urban change [

37,

40]. In a unified state that offered unlimited access to inland resources, official emphasis was placed primarily on urbanized and strongly Hellenized coastal centers for political, military and economic reasons. The coastal cities, such as Nea Paphos, Marion-Arsinoe, Kourion, Amathous, Soloi and Salamis (

Figure 1), undoubtedly mirror Ptolemaic strategic interests in coastal port bases and settlements as well as maritime activity and power [

43]. Although Cyprus was ready to adapt Hellenic forms of administration, it was indeed Ptolemaic rule (and particularly that of the second and first centuries BC) that established city life and institutions, such as

boule, gymnasia and theatres, in accordance with the cities of the Hellenistic world elsewhere [

44,

45]. While we can usually assume the shape of the Hellenistic cities through the epigraphic record, the current remains of all the coastal urban centers date to the Roman period, and they fully adhere to the monumental character of a standard Roman city.

The gravitation of people towards these coastal cities was of greater historical significance. Several archaeological surface surveys on the island have noted a full Hellenistic and Roman countryside settlement pattern, which was followed by a general contraction from the second through the fourth centuries BC [

46]. According to Marcus Rautman [

46], rural settlement began to decline around the second century AD, as demonstrated by published survey data in Cyprus and elsewhere; evidence of Severan prosperity, which often is taken to represent the apogee of Roman Cyprus, is overwhelmingly urban and may have come about at the expense of the countryside. However, the settlement patterns of the transitional phases are not entirely consistent, and new regional archaeological survey projects need to address those issues, exploring pastoral, agricultural and other economic activities and how these are related to the various political situations and to the siting of sanctuaries. We would preliminarily observe however, that the widespread abandonment of the extra-urban shrines, no less than the elaboration of public cults in the cities, set the stage for profound social and religious reassessments [

46] that go back to the Hellenistic period, and have to be studied within the context of the transition from segmented to unitary government and administration.

Moving to continuity and abandonment in sacred landscapes, the importance of memory is a crucial factor [

14,

18]. It is important to see sacred landscapes not simply as constructs but also as a complex and dynamic reaction to Ptolemaic, and later to Roman incorporation, and to investigate what was remembered, when, where and how. The continuity or discontinuity of the extra-urban cult activity should be keyed to multi-polar power relations and memory trends. Local and non-local elites, in their effort to define or redefine their relationships with the land for political and economic reasons, or in order to naturalize or legitimate authority, could have used sanctuaries to demonstrate their status. As the epigraphic evidence reveals, new social divisions and affiliations within Cypriot society as a whole, but also within individual communities—intertwined with other sources of power—were also promoted through the very agency of cult. However, during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the need for political elites to define the link between territory and city, for other than administrative or economic reasons, should have become less and less important. If extra-urban sanctuaries played a frontier or liminal role in the perpetuation of city-kingdom identities, now, under a new unified political organization, they eventually lost their territorial significance.

The dedication of monumental statues in many extra-urban sanctuaries by the Cypriot elite, imitating Ptolemaic prototypes—but at the same time adhering to the long typological and ritual Cypriot traditions—also reveals continuity in cult activity and traditions. The insertion of Hellenized and portrait-like features into statues whose general format remained strongly Cypriot might suggest a controversial ideological move [

37,

47,

48]: not only the incorporation of Ptolemaic ideas (and ideals) into the Cypriot mentality, but also the accommodation of Ptolemaic rule into a Cypriot context, i.e., the incorporation of Cypriot ideas (and ideals) into the Ptolemaic ideology. Within the material record, resistance could be expressed in a covert manner, and involve the continuation of religious practices or the maintenance of a traditional material culture. Terms such as ‘resistance accommodation’ and ‘resistance adaptation’ have been widely used in contemporary archaeological literature to indicate that resistance was not an either/or proposition, but rather an ongoing, subtle and usually muted process [

49]. In time, and when reaching the Roman period, many of the elites of the city-kingdoms would have disappeared or been suppressed. By the first century AD, therefore, when a more unified and centralized politico-religious system seems to have been well established, the tradition of dedicating limestone portrait-like sculptures in extra-urban sanctuaries eventually died out, along with the majority of the long-standing extra-urban sanctuaries. After the early Roman period, we find hardly any limestone ‘portraits’ in a Cypriot sanctuary; they all belong to the funerary sphere, carved on a number of grave reliefs [

50,

51,

52]. The material culture of the Cypriot sanctuaries of the Roman period clearly suggests that identities and modes of self-expression had significantly shifted and transformed.

Religion represented a close linkage between local cult and local identity. Although we cannot simply speak of many cultural identities in Iron Age Cyprus, the shifting from many political city-identities to one had consequences, such as the interruption of promoting particular local cults. In addition, just as people moved in the landscapes, creating, modifying, destroying or abandoning places or institutions, in the same way their identity is defined, re-defined or restricted. Such an embodiment could enable us to define how people transformed their identities through landscapes, and at the same time how landscapes themselves were transformed, adapting to the new socio-economic relations, as well as to the new socio-political identities and memory realities. Changes that occurred on different levels in Hellenistic and Roman societies influenced the religious sphere, cult practice and consequently the sacred landscapes. On the other hand, sacred landscapes themselves should not be seen as a passive reflector of social practice, but rather as an active expresser of it; functioning under a new unified politico-economic system, sacred landscapes eased the transformation of human identities and perception of space.

The image of the ‘Cypriot Goddess’ is the paradigmatic example for illustrating the transformations that occurred as the island moved from segmented to unitary government and administration, and the complexity of that process. Her artistic representations on sculpture and terracotta figurines, for example, show that by the Hellenistic, and later the Roman period, she was fully Hellenized, conforming to the iconography of Greek Aphrodite [

40,

53,

54] (

Figure 4). Moving from stylistic to cultic analysis, however, is simply impossible without considering the fact that some local particularities in her cult survived well beyond the end of the Hellenistic period. The most illustrative example comes from the ‘archaic’ cult place of Aphrodite in Palaepaphos, which under Ptolemaic and Roman rule was developed into a pan-Cyprian sanctuary and where strong epigraphic evidence for the practice of the ruler and imperial cult exists [

55]: not only the architecture of the sanctuary remains close to the traditional Cypriot

temenos from the Late Bronze Age to the end of the Roman period, but also the cult statue of the goddess keeps the aniconic shape of a

baetyl.

Such continuities should be viewed in relation to both the local cultural identity and the character of politico-religious agency and ideology, which through various accommodations and transformations, seems to have reproduced the established socio-cultural norms. Nonetheless, as well-documented evidence from epigraphy or the diachronic study of cult in excavated sanctuaries—such as those of Palaepaphos and Amathous—reveal, a more unifying reorganization of cult can be noted during the Hellenistic and Roman periods [

39]. Changing economic conditions within the Cypriot cities under a unitary government and administration also entailed some significant changes in financing, and as a result, in the sociological structure of their religion. In the Hellenistic, and especially in the Roman periods, financial management eventually shifted from the city-state to a more unified and centralized control. The most important bearer of a unifying ideology should have been played by the

Koinon Kyprion (Union of Cypriots), dedicated to the promotion of the Ptolemaic, and later the imperial cult [

44,

55,

56].

Among the large distribution of settlements in the various published archaeological survey projects and in the Cyprus Survey Inventory, one of us has located 23 sites that might have functioned as a sanctuary

ex novo in the Hellenistic period [

37]. Next to the Ptolemaic official attention towards old traditional urban sanctuaries [

55,

57,

58,

59], Greek-style temple architecture is added to the Cypriot sacred landscapes quite late in the Hellenistic period, not in the extra-urban environment of Cyprus, but in the direct environs of the major urban centers, where Ptolemaic power and cult would have been practiced more markedly. On the other hand, during the early Hellenistic period, sanctuaries

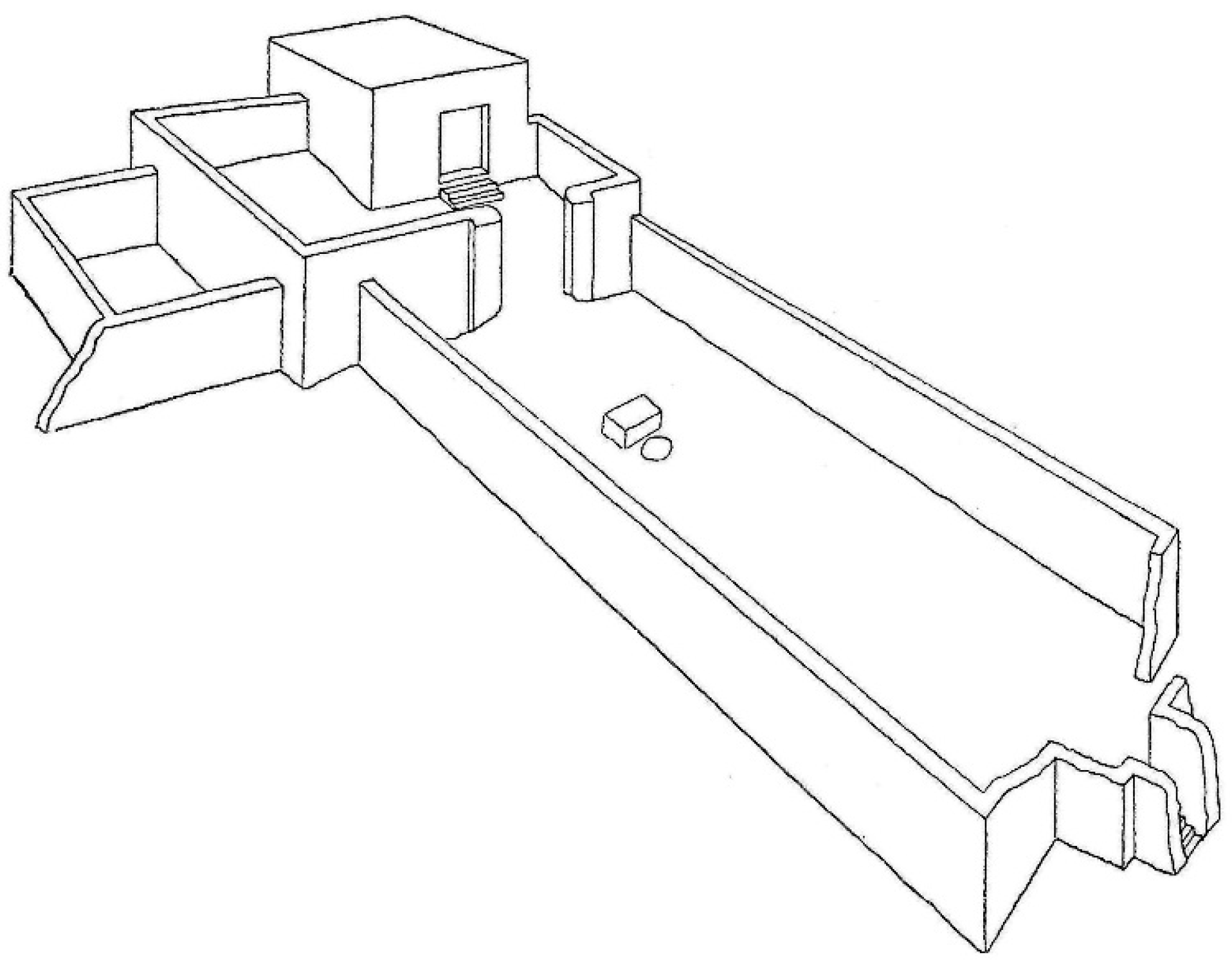

ex novo, such as that of Soloi-Cholades (

Figure 5), with strong allusions to Ptolemaic cult, were built following the traditional Cypriot architecture of the Iron Age Cypriot

temenos, probably drawing on the existing religious sentiment and cult [

60].

As mentioned above, by the Roman period many inland Iron Age extra-urban sanctuaries were deserted and only a few coastal sanctuaries remodeled and enlarged (

Figure 2); some of those sanctuaries, such as that of Apollo at Kourion and Aphrodite at Amathous, also received monumental podium temples. While excavation and survey projects confirm that an

ex novo foundation of sanctuaries was rare in the Roman period [

61], the use of pre-existing extra-urban sanctuary sites was visibly reduced. Only 40 possible sanctuary sites (including urban and extra-urban sites) preserved evidence of cults in the Roman period, and these sites included important ‘time-honored’ sanctuaries in the environs of urban coastal centers, such as the sanctuaries of Apollo

Hylates at Kourion, of Aphrodite at Palaepaphos and Amathous, and of Zeus at Salamis. It seems that the Romans invested in rebuilding and temple constructions, usually at those same primarily urban sites as their Ptolemaic predecessors.

Summarizing the evidence presented above, it becomes clear that state revenues, financing for state festivals, and the building and upkeep of sanctuaries went towards more prestigious, high-status urban sanctuaries, such as those of Aphrodite in Palaepaphos and Amathous, or of Zeus in Salamis; this helped created a more unified national politico-religious identity. The primacy of these sanctuaries by the Roman period was confirmed by Tacitus (

Annales 3.62), who reminded us that the Senate confirmed their rights of amnesty in 22 AD. Over the next 200 years, these cults increasingly became associated with the island’s identity as a Roman territory. Images of the Palaepaphos sanctuary and the standing figure of Zeus Olympios appear both singly and paired on coins issued by the

Koinon Kyprion for the first through the third century AD. The heavy promotion of these primary shrines, together with temples of the imperial cult at Nea Paphos and Kourion, for example, may be seen as part of Roman efforts to unify and consolidate the island province [

46]. Following the Severan period, we know very little regarding Cypriot sacred space during the third and fourth centuries AD. The stratigraphy, material culture, and architecture related to the post-Severan sacred landscapes remains to be identified, published and sufficiently analyzed. We hope that scholarship will soon manage to fill or explain the gap we currently face during the third and fourth centuries AD.

4. From Roman Times to Christian Late Antiquity

Following the Severan period and the social transformations taking place during Late Antiquity (late fourth to middle seventh centuries AD), the urban temples of Cyprus eventually start declining. A weakened economy, and the subsequent imperial neglect during the third century AD, contributed to fundamental social realignments and dramatic ideological shifts [

46]. Thus, town councils and magistrates did not maintain declining sanctuaries, which eventually closed because of earthquake damages during the mid-fourth century AD. The official establishment of Christianity, the economic prosperity that Cyprus started enjoying, and the shift of political control (at the local level) from imperial families to Christian elites and bishops contributed to the transformation of the sacred townscapes and landscapes of Cyprus [

62,

63,

64]. Cypriot bishops worked in the shadow of damaged temples at the urban environments of Paphos, Amathous, Kourion and Salamis, resacralizing space by building cathedrals and other large basilicas in renovated parts of their flourishing cities [

46]. During Late Antiquity, settlements and new cult sites dating to the fifth century AD, such as the basilicas at Karpasia, Lapithos, and Tremithous (

Figure 1), document both the expansion of rural settlement and the successful Christianization of the countryside [

46].

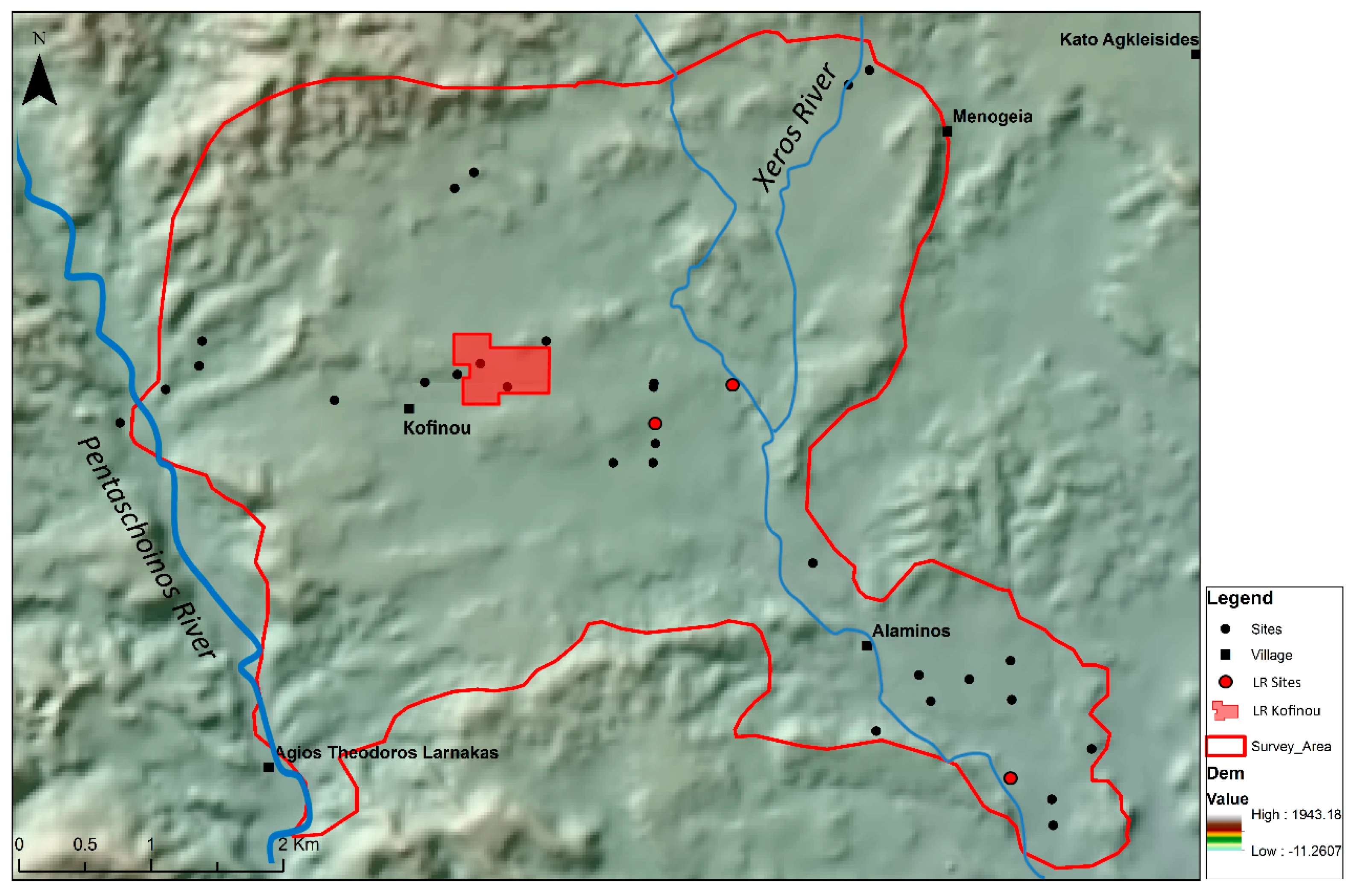

SeSaLaC is currently testing the above framework through a recently initiated archaeological surface survey project in the area of the Xeros river valley in the Larnaca district, with the modern village of Kofinou lying in its center (

Figure 6). Preliminary GIS mapping and analyses of Cypriot Late Antique churches in relation to the road networks and arable land [

65] aim to reveal—similarly to the function of ancient sanctuaries—the function of these countryside basilicas in the context of economic and symbolic landscapes. The analyses confirm that Christian basilicas are found in association with rural establishments (e.g., villages), local central places (e.g., towns, agro-towns and ports or coastal

emporia), and other significant economic and communication nodes (e.g., road networks, rivers and agriculturally rich areas). The basilica churches at Kalavassos-Kopetra for instance (

Figure 1), constructed in the sixth and seventh centuries AD on a hill in the middle of the Vasilikos valley, acted as regional economic nodes at a central point for the collection and distribution of imported and local products [

65,

66].

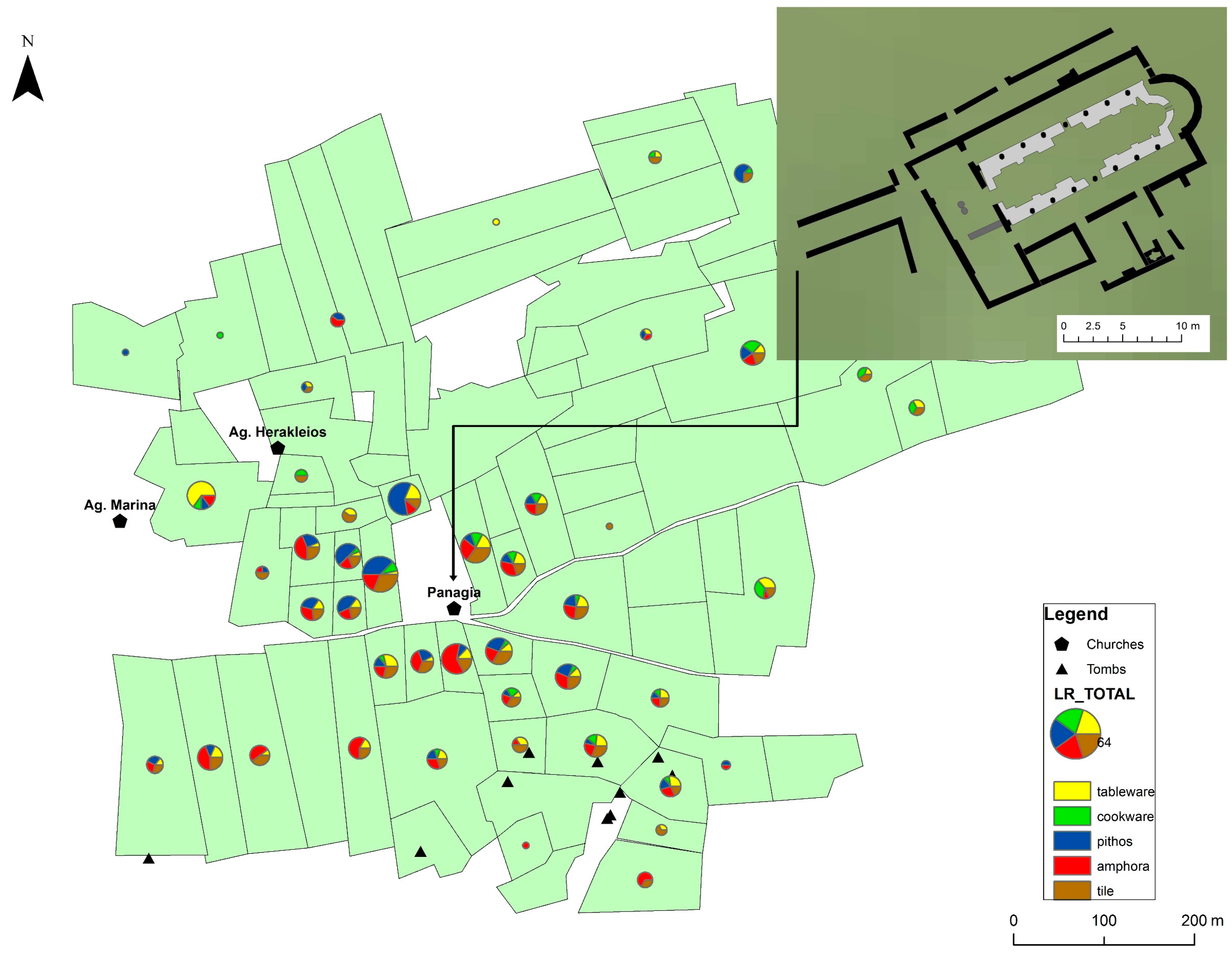

Our investigation in the region of Kofinou so far has indeed provided evidence for a much more intensive Late Antique settlement activity (in comparison to the preceding Roman era) around an Early Christian basilica (dedicated to

Panagia, Virgin Mary) dated to the late sixth century AD (

Figure 7). The archaeological evidence, topographic parameters, extensive surrounding agricultural territory and comparative evidence from other excavated and surveyed archaeological sites suggest that in Late Antiquity the site of Kofinou, around the church of Panagia, played a central role within its ‘settlement chamber’ or micro-region, coincidentally overlapping with our survey area [

67,

68]. Looking at population figures based on excavation and survey evidence, the site of Kofinou itself should have provided housing to approximately 250–300 families during its maximum size in the sixth and seventh centuries AD, when the built space around the basilica, according to surface ceramic scatters, reached almost 13 ha. The excavated basilica must have functioned as the focal point of the settlement, standing at its approximate center, dominating its immediate environs and marking a primary approach to the site.

The extent of the site, the rich ceramic evidence dated to Late Antiquity, and the presence of an important monument of Christian worship in an otherwise extensive and mostly fertile agricultural region can only point to the status of Kofinou as a second-rank settlement, and as the main habitation site of the micro-region of the Xeros valley. Such secondary settlements in the countryside had a major role to play as local centers, that is, as important loci within the territory of their ‘settlement chamber’, acquiring an important role in agricultural production, processing and distribution of goods, and sometimes administrative functions as well. If, then, Kofinou comprised a second-rank settlement, which we would define here as an ‘agro-town’, one needs to identify the closest primary center, or regional central place, and other minor rural establishments. Although this remains guesswork at this stage, the region’s primary center should have been the city and bishopric of Kition, present-day Larnaca, 23 km northeast. In this context, it is worth looking at similar examples elsewhere in Cyprus.

In the neighboring region of Kalavasos-Kopetra, 12 km southwest of Kofinou, excavations have unearthed the remains of a prosperous rural settlement of 4 ha, home of 100 families, together with three churches, serving as physical and social landmarks for local residents [

69]. According to the excavator, the churches and other archaeological evidence in Kalavasos reflect the economic success of this Cypriot community, identified as a ‘market village’ and its control of transport and exchange on a sub-regional level [

69].

The second example concerns the site of Pyla-Koutsopetria, 32 km northeast of Kofinou, where a surface survey has identified an enormous coastal site of 40 ha, with plentiful ceramic evidence confirming the agricultural and quarrying profession of its inhabitants, but most importantly, their engagement in maritime trade as their main economic activity [

63]. Moreover, monumentality is also present at the site. Excavations by the Department of Antiquities in the past have revealed a basilica with

opus sectile floors, while the results of recent geophysical prospection by the University of Dakota indicate the existence of more churches at the site [

63]. Thus, Pyla-Koutsopetria functioned as an

emporion in Late Antiquity, involved in the inter-regional distribution of Cypriot goods.

It goes without saying that every respectful second-rank settlement—in our case the agro-town of Kofinou—should be the focus and local center of a series of satellite minor rural establishments, such as hamlets, villas and farmsteads. Indeed, three small loci of ceramic concentrations east of the large settlement of Kofinou, comprising mainly of roof tile, transport and storage vessels, have been interpreted as small farms, housing a number of farming families closer to their fields (

Figure 8).

Farmsteads and villa estates are amongst the commonest rural sites identified in Cyprus and beyond (from Spain and Italy to the Levant) throughout Late Antiquity. Previous survey work on the island (e.g., in the territory of Kourion) has revealed that farmsteads were usually small in size (ranging between 0.01 and 0.4 ha), had access to fresh water, and were located in prominent positions overlooking the surrounding countryside and the sea [

70].

The pattern that emerges when one focuses on archaeological evidence from our site dated to the Late Antique era is of particular importance here. The micro-region of Kofinou, very much as the micro-regions of Pyla-Koutsopetria and Kalavasos-Kopetra, was characterized by the presence of a main settlement with associated basilicas. Thus, in a way, the presence of one or more basilicas at these places possibly indicated the settlement’s status as a local center, with churches supervising (in a way) agricultural, processing, distribution and sometimes industrial activities. These secondary places may have varied in size and function: Pyla-Koutsopetria, a port-town of 40 ha should have provided home to 800–1000 families and functioned as an

emporion distributing goods inter-regionally; Kofinou, an agro-town of 13 ha must have accommodated up to 300 families and participated in intensive agricultural production, storage and distribution of goods to nearby cities and port-towns; Kalavasos-Kopetra, a market village of 4 ha with a population of 100 families functioned as a principal market for local products. The primary center or regional central place, towards which these second-rank settlements were oriented, is always a nearby city, usually with a bishop, such as Kition to the east of Kofinou and Amathous to the west. Finally, third-rank settlements were satellite minor farming establishments without a church, or settlements occupied seasonally by a labor force residing in cities, port-towns, agro-towns and market-villages, and commuting seasonally between secondary settlements and their farms. This settlement hierarchy for Cyprus is always adapted by SeSaLaC according to the period under investigation, and is primarily based on deterministic factors of what makes central and secondary places. It should be born in mind, however, for periods about which archaeological data or textual evidence are confined or lacking, that central-place functions might be dispersed between a variety of sites and places, while a central person might be as important as a central place [

71]. It is evident that there is clearly much more going on in the case of the Xeros valley (and other fertile and well-populated regions in Cyprus) than a three-level settlement hierarchy and dots on the map, as can be illustrated by land capacity and population estimates for the period (see below).

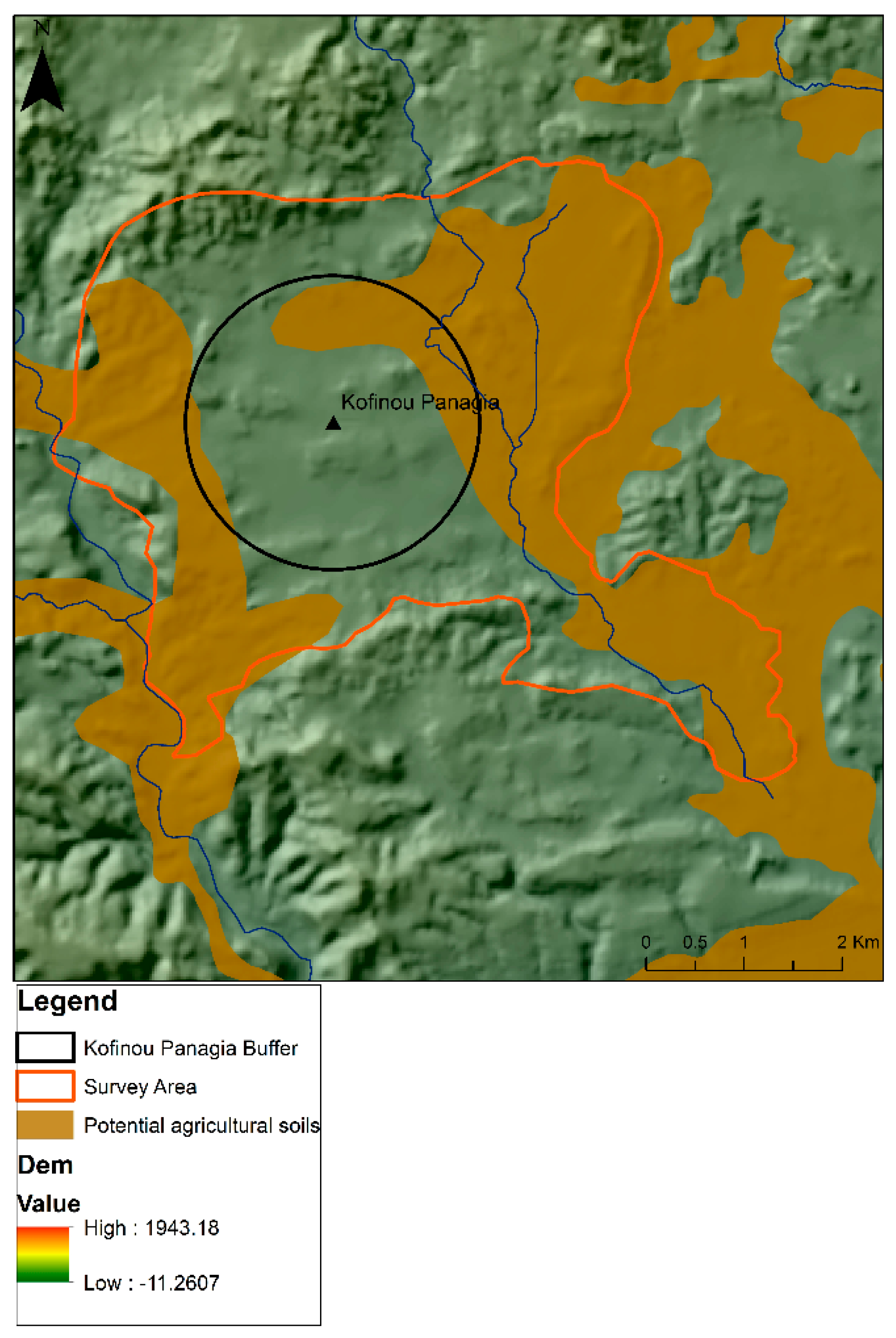

Taking Kofinou as a secondary settlement in Late Antiquity, one wonders whether the land available in its micro-region and the approximate number of people that lived in the settlement were actually compatible. Although the immediate surroundings of the Christian basilica at Kofinou nowadays give the impression of a rich and intensively cultivated landscape, the

Soil Atlas of Europe shows that the best and most fertile soils within our survey area and the Kofinou settlement chamber make a total of 1510 ha (

Figure 9). Interestingly, the Late Antique settlement itself lies in the middle of less fertile soils, a very wise choice on behalf of its inhabitants, making use of less productive areas for their settlement’s built space, as well as for less demanding cultivations, such as vegetable gardens and olive groves or as pasture land. More demanding crops, such as wheat and vines, would have been cultivated in the areas with the best soils, lying 800 m away from the settlement. Considering that approximately 300 families were living in Kofinou, and taking into account that 3.6 ha of land were required per family to meet their subsistence needs in pre-industrial times [

72], we arrive at the figure of 1080 ha needed for feeding the population of Kofinou. That means that the remaining 430 ha would be reserved for sustaining the population of satellite villas and farmsteads and, of course, for the export of a significant surplus that would bring in the necessary cash for the community to meet its tax obligations.

It becomes evident that basilica churches mark monumental space and feature prominently within settlements of some status in Late Antique Cyprus and beyond. Apart from their role as buildings of religiousness and piety or symbols of imperial ideology and Christian identity, churches became public meeting places and focuses of production, commercial and economic activities of civic and rural communities. Examples from different regions of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) are indicative of the basilica’s multiple roles. In urban environments, churches began to encroach on the traditional public spaces. Such basilicas, usually of monumental dimensions, occupy part of the public area of the town, replacing in a way the Roman

forum, and dominate the townscape, fitting into the town’s layout without necessarily becoming a haphazard conglomeration [

67]. The main basilica at Kourion can be a fine example of this. In peri-urban environments, extra-mural churches were usually placed along main road axes leading to the city in order to impress anyone travelling into town. In a rural context, agricultural resources seem to have been directly associated with the sighting of churches in Late Antique landscapes. Similarly to the ancient sanctuaries, Late Antique basilicas played an important role in inscribing social memory, territorial significance, and economic activities on the landscape. Last but not least, one of the roles that basilicas in rural environments seem to have assumed was that of supervisor of industrial, processing and storage activities. Excavated basilicas in Cyprus provide evidence for similar multiple roles. They appear to be encroaching civic public space, they are built close to gates and ports, in the periphery of cities and along major communication axes, but most importantly, some of them, especially urban ones, imply some kind of engagement in industry and water-management [

68]. The basilica and agro-town of Kofinou may have functioned in a similar fashion: as a collection, storage center, and distribution point of agricultural produce. A link has been suggested between oil production at basilica C at Peyia, Ayia Varvara in Amathous, the northern and southern basilicas at Arsinoe and their nearby harbors. Since some basilicas with industrial and storage installations had direct access to port facilities, it seems reasonable to assume that the church had interests in the export trade, which accounts for its wealth in the sixth and early seventh centuries AD. There is no reason to believe otherwise for the case of basilicas in secondary settlements, such as

emporia, agro-towns and market-villages. Evidence suggests that the coastal basilica at Pyla-Koutsopetria had direct access to port facilities and warehouses, while press weights and grinding stones from the vicinity of the basilicas at Kalavasos-Kopetra indicate involvement in the processing of agricultural goods [

63,

64]. The basilica and agro-town of Kofinou may have functioned in a similar fashion: as a collection and storage center, and distribution point of agricultural produce.