Supramolecular Chirality in Dynamic Coordination Chemistry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Supramolecular Chirality from Helicates to Foldamers

3. Dynamic Production and Inversion of Supramolecular Chirality in Octahedral Metal Complexes

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Voet, D.; Voet, J.G. Biochemistry, 4th ed; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann, H.; Hauptmann, M.; Niessing, D.; Lloyd, C.W.; Schäffnera, A.R. Helical growth of the Arabidopsis mutant tortifolia2 does not depend on cell division patterns but involves handed twisting of isolated cells. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila, J.; Vogan, K.J.; Tabin, C.J.; Belmonte, J.C.I. Mechanisms of left-right determination in vertebrates. Cell 2000, 101, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, T. Molecular genetic analysis of left–right handedness in plants. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2002, 357, 799–808. [Google Scholar]

- Samatey, F.A.; Imada, K.; Nagashima, S.; Vonderviszt, F.; Kumasaka, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Namba, K. Structure of the bacterial flagellar protofilament and implications for a switch for supercoiling. Nature 2001, 410, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.; Ren, J. Recognition and regulation of unique nucleic acid structures by small molecules. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 7283–7294. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Christensen, L.A.; Vasquez, K.M. Z-DNA-forming sequences generate large-scale deletions in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2677–2682. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, A.; Hiraga, K.; Imada, Y.; Hiejima, T.; Furuya, H. Screw-sense inversion characteristic of α-helical poly(β-p-chlorobenzyl l-aspartate) and comparison with other related polyaspartates. Biopolymers 2005, 80, 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.K.; Thomas, K.M.; Forbes, C.R.; Zondlo, N.J. Tunable control of polyproline helix (PPII) structure via aromatic electronic effects: An electronic switch of polyproline helix. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 5307–5314. [Google Scholar]

- Horng, J.-C.; Raines, R.T. Stereoelectronic effects on polyproline conformation. Protein Sci 2006, 15, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, F.X. Prolyl isomerases. Adv. Protein Chem 2002, 59, 243–281. [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino, L.; Sun, A.; Lu, P.-J.; Zhou, X.Z.; Balastik, M.; Finn, G.; Wulf, G.; Lim, J.; Li, S.-H.; Li, X.; et al. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates amyloid precursor protein processing and amyloid-β production. Nature 2006, 440, 528–534. [Google Scholar]

- Suk, J.-M.; Naidu, V.R.; Liu, X.; Lah, M.S.; Jeong, K.-S. A foldamer-based chiroptical molecular switch that displays complete inversion of the helical sense upon anion binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 13938–13941. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Lim, Y.-K.; Zhang, B.J.; Opsitnick, E.A.; Baik, M.-H.; Lee, D. Dendritic molecular switch: Chiral folding and helicity inversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 16812–16822. [Google Scholar]

- Opsitnick, E.A.; Jiang, X.; Hollenbeck, A.N.; Lee, D. Hydrogen-bond-assisted helical folding of propeller-shaped molecules: Effects of extended π-conjugation on chiral selection, conformational stability, and exciton coupling. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2012, 708–720. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Du, G.; Liu, K.; Jiang, L.; Ling, J.; Shen, Z. Chiroptical inversion induced by rotation of a carbon-carbon single bond: An experimental and theoretical study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Miyajima, D.; Itoh, Y.; Mori, T.; Tanaka, H.; Yamauchi, M.; Inoue, Y.; Harada, S.; Aida, T. C5-Symmetric chiral corannulenes: Desymmetrization of bowl inversion equilibrium via “intramolecular” hydrogen-bonding network. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10640–10644. [Google Scholar]

- Kolomiets, E.; Berl, V.; Lehn, J.-M. Chirality induction and protonation-induced molecular motions in helical molecular strands. Chem. Eur. J 2007, 13, 5466–5479. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y.; Flood, A.H. Flipping the switch on chloride concentrations with a light-active foldamer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 12838–12840. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, E.; Maeda, K.; Iida, H.; Furusho, Y.; Nagai, K. Helical polymers: Synthesis, structures, and functions. Chem. Rev 2009, 109, 6102–6211. [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura, K.; Ikai, T.; Kanoh, S.; Yashima, E.; Maeda, K. Switchable enantioseparation based on macromolecular memory of a helical polyacetylene in the solid state. Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.A.; Diemer, V.; Webb, S.J.; Clayden, J. End-to-end conformational communication through a synthetic purinergic receptor by ligand-induced helicity switching. Nat. Chem 2013, 5, 853–860. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki, M. Switching handedness in optically active polysilanes. J. Organomet. Chem 2003, 685, 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Park, Y.-S.; Rho, J.; Singh, R.; Nam, S.; Azad, A.K.; Chen, H.-T.; Yin, X.; Taylor, A.J.; et al. Photoinduced handedness switching in terahertz chiral metamolecules. Nat. Commun 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchineella, S.; Prathyusha, V.; Priyakumar, U.D.; Govindaraju, T. Solvent-induced helical assembly and reversible chiroptical switching of chiral cyclic-dipeptide-functionalized naphthalenediimides. Chem. Eur. J 2013, 19, 16615–16624. [Google Scholar]

- Sargsyan, G.; Schatz, A.A.; Kubelka, J.; Balaz, M. Formation and helicity control of ssDNA templated porphyrin nanoassemblies. Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 1020–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Pijper, D.; Jongejan, M.G.M.; Meetsma, A.; Feringa, B.L. Light-controlled supramolecular helicity of a liquid crystalline phase using a helical polymer functionalized with a single chiroptical molecular switch. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 4541–4552. [Google Scholar]

- San Jose, B.A.; Yan, J.; Akagi, K. Dynamic switching of the circularly polarized luminescence of disubstituted polyacetylene by selective transmission through a thermotropic chiral nematic liquid crystal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 126, 10817–10820. [Google Scholar]

- Borovkov, V. Supramolecular chirality in porphyrin chemistry. Symmetry 2014, 6, 256–294. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukube, H.; Shinoda, S. Lanthanide complexes in molecular recognition and chirality sensing of biological substrates. Chem. Rev 2002, 102, 2389–2403. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, H.; Terada, K.; Tsukube, H. Lanthanide tris(β-diketonates) as useful probes for chirality determination of biological amino alcohols in vibrational circular dichroism: Ligand to ligand chirality transfer in lanthanide coordination sphere. Chirality 2014, 26, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, K.-H.; Wild, F.R.W.P.; Blacque, O.; Berke, H. Alfred Werner’s coordination chemistry: New insights from old samples. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 10780–10787. [Google Scholar]

- Constable, E.C.; Housecroft, C.E. Coordination chemistry: The scientific legacy of Alfred Werner. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 1429–1439. [Google Scholar]

- Crassous, J. Transfer of chirality from ligands to metal centers: Recent examples. Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 9684–9692. [Google Scholar]

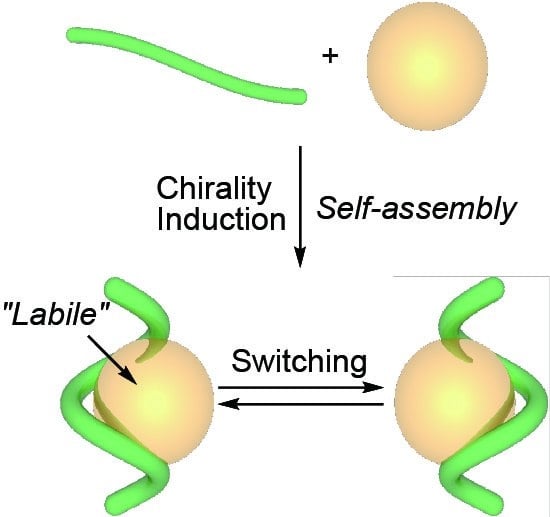

- Miyake, H.; Tsukube, H. Coordination chemistry strategies for dynamic helicates: Time-programmable chirality switching with labile and inert metal helicates. Chem. Soc. Rev 2012, 41, 6977–6991. [Google Scholar]

- Durot, S.; Reviriego, F.; Sauvage, J.-P. Copper-complexed catenanes and rotaxanes in motion: 15 years of molecular machines. Dalton Trans 2010, 39, 10557–10570. [Google Scholar]

- Forgan, R.S.; Sauvage, J.-P.; Stoddart, J.F. Chemical topology: Complex molecular knots, links, and entanglements. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 5434–5464. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, L.; Merbach, A.E. Inorganic and bioinorganic solvent exchange mechanisms. Chem. Rev 2005, 105, 1923–1959. [Google Scholar]

- Lehn, J.-M.; Rigault, A.; Siegel, J.; Harrowfield, J.; Chevrier, B.; Moras, D. Spontaneous assembly of double-stranded helicates from oligobipyridine ligands and copper(I) cations: Structure of an inorganic double helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 2565–2569. [Google Scholar]

- Piguet, C.; Bernardinelli, G.; Hopfgartner, G. Helicates as versatile supramolecular complexes. Chem. Rev 1997, 97, 2005–2062. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, M. “Let’s twist again” sdouble-stranded, triple-stranded, and circular helicates”. Chem. Rev 2001, 101, 3457–3497. [Google Scholar]

- Howson, S.E.; Scott, P. Approaches to the synthesis of optically pure helicates. Dalton Trans 2011, 40, 10268–10277. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, H.; Ikeda, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Furusho, Y.; Yashima, E. Synthesis of complementary double-stranded helical oligomers through chiral and achiral amidinium-carboxylate salt bridges and chiral amplification in their double-helix formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 3419–3432. [Google Scholar]

- Furusho, Y.; Goto, H.; Itomi, K.; Katagiri, H.; Miyagawa, T.; Yashima, E. Synthesis and optical resolution of a Cu(I) double-stranded helicate with ketimine-bridged tris(bipyridine) ligands. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 9795–9797. [Google Scholar]

- Boiocchi, M.; Brega, V.; Ciarrocchi, C.; Fabbrizzi, L.; Pallavicini, P. Dicopper double-strand helicates held together by additional π–π interactions. Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 10643–10652. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, H.; Furusho, Y.; Yashima, E. Diastereoselective imine-bond formation through complementary double-helix formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 7250–7253. [Google Scholar]

- Kovaříček, P.; Lehn, J.-M. Merging constitutional and motional covalent dynamics in reversible imine formation and exchange processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 9446–9455. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler, A.-M.; Lehn, J.-M.P. Coupled nanomechanical motions: Metal-ion-effected, ph-modulated, simultaneous extension/contraction motions of double-domain helical/linear molecular strands. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 3400–3409. [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto, Y.; Kojima, T.; Hiraoka, S. Rate-determining step in the self-assembly process of supramolecular coordination capsules. Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 4167–4172. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S.; Ishido, Y.; Fujita, M. Remarkable stabilization of M12L24 spherical frameworks through the cooperation of 48 Pd(II)-pyridine interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 6064–6065. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, H.; Ueda, M.; Murota, S.; Sugimoto, H.; Tsukube, H. Helicity inversion from left- to right-handed square planar Pd(II) complexes: Synthesis of a diastereomer pair from a single chiral ligand and their structure dynamism. Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 3721–3723. [Google Scholar]

- Eerdun, C.; Hisanaga, S.; Setsune, J. Single helicates of dipalladium(II) hexapyrroles: Helicity induction and redox tuning of chiroptical properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 929–932. [Google Scholar]

- Akine, S.; Hotate, S.; Nabeshima, T. A molecular leverage for helicity control and helix inversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 13868–13871. [Google Scholar]

- Akine, S.; Sairenji, S.; Taniguchi, T.; Nabeshima, T. Stepwise helicity inversions by multisequential metal exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 12948–12951. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, R.; Lehn, J.-M.; de Cian, A.; Fischer, J. Self-assembly, structure, and spontaneous resolution of a trinuclear triple helix from an oligobipyridine ligand and NiIIions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1993, 32, 703–706. [Google Scholar]

- Lehn, J.-M. Toward self-organization and complex matter. Science 2002, 295, 2400–2403. [Google Scholar]

- Hasenknopf, B.; Lehn, J.-M.; Kneisel, B.O.; Baum, G.; Fenske, D. Self-assembly of a circular double helicate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1996, 35, 1838–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Hasenknopf, B.; Lehn, J.-M.; Boumediene, N.; Dupont-Gervais, A.; van Dorsselaer, A.; Kneisel, B.; Fenske, D. Self-assembly of tetra- and hexanuclear circular helicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 10956–10962. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.J.; Clary, K.N.; Bergman, R.G.; Raymond, K.N.; Toste, F.D. A supramolecular approach to combining enzymatic and transition metal catalysis. Nat. Chem 2013, 5, 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Aboshyan-Sorgho, L.; Cantuel, M.; Bernardinellib, G.; Piguet, C. Looking for the origin of the switch between coordination-captured helicates and catenates. Dalton Trans 2012, 41, 7218–7226. [Google Scholar]

- Imbert, D.; Cantuel, M.; Bünzli, J.-C.G.; Bernardinelli, G.; Piguet, C. Extending lifetimes of lanthanide-based NIR emitters (Nd, Yb) in the millisecond range through Cr(III) sensitization in discrete bimetallic edifices. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 15698–15699. [Google Scholar]

- Aboshyan-Sorgho, L.; Nozary, H.; Aebischer, A.; Bünzli, J.-C.G.; Morgantini, P.-Y.; Kittilstved, K.R.; Hauser, A.; Eliseeva, S.V.; Petoud, S.; Piguet, C.; et al. Optimizing millisecond time scale near-infrared emission in polynuclear chrome(III)–lanthanide(III) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 12675–12684. [Google Scholar]

- Howson, S.E.; Allan, L.E.N.; Chmel, N.P.; Clarkson, G.J.; van Gorkum, R.; Scott, P. Self-assembling optically pure Fe(A–B)3 chelates. Chem. Commun 2009, 1727–1729. [Google Scholar]

- Howson, S.E.; Allan, L.E.N.; Chmel, N.P.; Clarkson, G.J.; Deeth, R.J.; Faulkner, A.D.; Simpson, D.H.; Scott, P. Origins of stereoselectivity in optically pure phenylethaniminopyridine tris-chelates M(NN′)3n+ (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni and Zn). Dalton Trans 2011, 40, 10416–10433. [Google Scholar]

- Ousaka, N.; Grunder, S.; Castilla, A.M.; Whalley, A.C.; Stoddart, J.F.; Nitschke, J.R. Efficient long-range stereochemical communication and cooperative effects in self-assembled Fe4L6 cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 15528–15537. [Google Scholar]

- Howson, S.E.; Bolhuis, A.; Brabec, V.; Clarkson, G.J.; Malina, J.; Rodger, A.; Scott, P. Optically pure, water-stable metallo-helical “flexicate” assemblies with antibiotic activity. Nat. Chem 2012, 4, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, A.D.; Kaner, R.A.; Abdallah, Q.M.A.; Clarkson, G.; Fox, D.J.; Gurnani, P.; Howson, S.E.; Phillips, R.M.; Roper, D.I.; Simpson, D.H.; et al. Asymmetric triplex metallohelices with high and selective activity against cancer cells. Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 797–803. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Howson, S.E.; Dong, K.; Gao, N.; Ren, J.; Scott, P.; Qu, X. Chiral metallohelical complexes enantioselectively target amyloid β for treating alzheimer’s disease. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 11655–11663. [Google Scholar]

- Castilla, A.M.; Ramsay, W.J.; Nitschke, J.R. Stereochemistry in subcomponent self-assembly. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 2063–2073. [Google Scholar]

- Ousaka, N.; Clegg, J.K.; Nitschke, J.R. Nonlinear enhancement of chiroptical response through subcomponent substitution in M4L6 cages. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 1464–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Castilla, A.M.; Ousaka, N.; Bilbeisi, R.A.; Valeri, E.; Ronson, T.K.; Nitschke, J.R. High-fidelity stereochemical memory in a FeII4L4 tetrahedral capsule. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 17999–18006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, Q.-F.; Hart-Cooper, W.M.; DiPasquale, A.G.; Toste, F.D.; Bergman, R.G.; Raymond, K.N. Chiral amide directed assembly of a diastereo- and enantiopure supramolecular host and its application to enantioselective catalysis of neutral substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 18802–18805. [Google Scholar]

- Ousaka, N.; Takeyama, Y.; Iida, H.; Yashima, E. Chiral information harvesting in dendritic metallopeptides. Nat Chem 2011, 3, 856–861. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, H.; Yoshida, K.; Sugimoto, H.; Tsukube, H. Dynamic helicity inversion by achiral anion stimulus in synthetic labile cobalt(II) complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 6524–6525. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, H.; Sugimoto, H.; Tamiaki, H.; Tsukube, H. Dynamic helicity inversion in an octahedral cobalt(II) complex system via solvato-diastereomerism. Chem. Commun 2005, 4291–4293. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, H.; Kamon, H.; Miyahara, I.; Sugimoto, H.; Tsukube, H. Time-programmed peptide helix inversion of a synthetic metal complex triggered by an achiral NO3− anion. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 792–793. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, H.; Hikita, M.; Itazaki, M.; Nakazawa, H.; Sugimoto, H.; Tsukube, H. A chemical device that exhibits dual mode motions: Dynamic coupling of amide coordination isomerism and metal-centered helicity inversion in a chiral cobalt(II) complex. Chem. Eur. J 2008, 14, 5393–5396. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miyake, H. Supramolecular Chirality in Dynamic Coordination Chemistry. Symmetry 2014, 6, 880-895. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym6040880

Miyake H. Supramolecular Chirality in Dynamic Coordination Chemistry. Symmetry. 2014; 6(4):880-895. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym6040880

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiyake, Hiroyuki. 2014. "Supramolecular Chirality in Dynamic Coordination Chemistry" Symmetry 6, no. 4: 880-895. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym6040880