1. Introduction

The Declaration of Human Rights, signed in Paris in 1948, recognizes that everyone has the right to social security and economic, social, and cultural rights indispensable to their dignity [

1]. More specifically, Macias Santos [

2] defines social security in Mexico as a general and homogeneous system of benefits, of public law and state supervision, whose purpose is to guarantee the human right to health, medical assistance, protection of the means of subsistence, and the social services necessary for individual and collective well-being through the redistribution of national wealth.

As a result of women’s desire for having their own spaces in the modern city, and as a tool for improving the social security of Mexican families, the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS, after the Spanish initials for Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social) founded, in 1956, the program Casa de la Asegurada (the term will be left in Spanish to highlight the gender focus that is lost when translated to the English “Home of the Insured”), the subject of this study. The program was conceived as one of the most modern at the time, understanding “to be modern” as Marshall Berman says, to find oneself in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, the transformation of ourselves and the world, and that, at the same time, threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, and everything we are [

3]. It was made to support all Mexican’s social security through women’s role as unifiers of the family and proposed that, through the acquisition of specific knowledge by women, they could lead Mexican families towards a better quality of life, emphasizing family ties, daily life, and popular values. These three values are not considered characteristic of modernity, as Rita Felski points out in “The Gender of Modernity” [

4].

In the international landscape, before the implementation of Casa de la Asegurada, several women’s movements were taking place that aimed to modify their relationship with public space. For example, Municipal Housekeeping, a group of women established at the start of the 20th century in the east coast of the US, was in charge of public space maintenance. Moreover, the popular library “Les Dones i l’ Institut de Cultura,” founded in 1909 in Barcelona by Francesca Bonnemaisson and the group “dones cooperadores,” and The Women’s Library (formerly The Library of the London Society for Women’s Service), founded in 1926, both of which allowed women to access knowledge without the support of the church and implied in their names the sexualization of these urban spaces that were traditionally masculine [

5]. In the same period, there was a boom of home economists like Christine McGaffey Frederick and Lillian Gilbreth. Frederick wrote the books “Household Engineering, Scientific Management in the Home” in 1919, in which she translates Frederick Taylor’s scientific production ideas to domestic work, “The new Housekeeping: efficiency studies in Home Management” in 1914, and “You and your Kitchen,” which proposes women liberation through spending less time in the kitchen. Gilbreth wrote the books “The Home and Her Job” in 1927, in which she proposes efficient house maintenance and defeminization of house chores techniques, and “Motion study in the Household” in 1912, which describes a new kitchen layout to reduce women’s domestic workload. In Europe, other books were written regarding household management influenced by Frederick’s ideas: “Die neue Wohnung: Die Frau als Shöpferin” (The New Apartment: the Woman as Creator) by Bruno Taut in 1928; “Das Wohnhaus von Heute” (The House Today) by Grete y Walter Dexler, in 1928; and “So wollen wir wohnen” (This is How We Want to Live) by Ludwig Neundörfer.

It is worth noting figures like Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, who design the Frankfurt kitchen that aims to reduce workload in household management, and Erna Meyer and Hilde Zimmermann, whose knowledge in household economy influenced the German house redefinition, participating in Stuttgart’s Weissenhof in 1927 [

5].

All these ideas helped inspire activity programs of the Casas de la Asegurada, searching for efficiency in the domestic work done by women and allowing that this, along with a smaller house to manage, facilitated access to different individual, social, and political activities for women.

However, it is important to highlight the reflections of Susan R. Henderson and Dolores Hayden about these topics, as they think that household economists’ texts gave credibility to women’s redomestication as a feminist program, giving the false notion that women, through participation processes, had informed about implementing these changes [

6]. They also indicate that any contribution of women on this matter is a gimmick to make them collaborate in their own domination [

7]. On the other hand, Zaida Muxi complements this affirmation and states that these women not only added improvements to women’s domestic work conditions but also fought for women’s rights like access to voting, education, and professional work, recognizing the value of their work towards gender equality [

5].

All these contributions, regardless of their focus, were stopped by the end of World War II. From this moment, women’s presence in the production and public spaces was considerably reduced. It is here when the idea of the American Dream arises. When the productive and reproductive spheres are separated, and housing is sold as the dreamed paradise to women. Hence, the private woman reappears, a woman that, to meet the patriarchal expectations, had her activities and role defined, as well as how her image and manners should be [

5] The above is the context in which the program Casa de la Asegurada is born.

According to the Latin-American architect Odilia Suárez, the substance of every creative action is knowing what it is wished to achieve, interpret, reject, solve, create, or communicate at a social level. Depending on these objectives, and as a bridge between them and forms built, are the “programs”. Therefore, creating valid programs is helping build society itself [

8]. From this affirmation, and in relation to the topic of study, the main question of this investigation arises: Is it possible that, through the creation of new architectural programs, women empowerment can be encouraged in search of gender equality? And this triggers secondary questions like How should these facilities’ programs be developed so that they do not become obsolete with time and gender roles changes? In which way should these be designed so that women feel empowered? And What are the architectural supports that can host these new programs?

These questions directly contribute to the current international debate surrounding the Sustainable Development Goals of the New Urban Agenda of the United Nations, specifically Goal 5: “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls,” Target 5.4: “Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure, and social protection policies, and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate,” and Goal 11: “Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.” This is why the study is considered pertinent, as it can contribute with reflections in search for tools that can provide solutions to these inquiries.

Due to all this, it is considered essential to revise and analyze the developed programs throughout history that aimed to support women empowerment at different levels, studying the operation, program, and architectural proposal of their facilities to identify successes and errors. Among these, is the Casa de la Asegurada program in Mexico, forgotten in the history of architecture and of the large Mexican housing complexes, and which is pertinent to review as a case study from a gender perspective that helps to approach in depth its objectives, program, and link with large housing complexes to understand the inconsistencies produced over time between the first proposals that sought the economic, spiritual, and social liberation of women, as described in its foundational texts [

9] and later proposals that suggested objectives and activities that did not deviate from the accepted patterns of life where men have the dominant role and women are relegated to the care of the household.

This article is part of a larger research project still in progress that analyzes these Casas under the hypothesis that the incorporation of facilities inside large housing complexes with adequate programs, and a clear architectonic and urbanistic representativeness inside public space, could help achieve gender equality, empower women and girls, and make inclusive and safe cities. Thus, the investigation is done through three general approaches: (1) their operation, impact on Mexican insured women, and subsequent transformation into Health, Security, and Family Welfare Centers (Centros de Seguridad Salud y Bienestar Familiar), relegating women to a secondary role; (2) the performance of the Casas de la Asegurada within the housing complexes in terms of urban planning and the creation of community life; and (3) the architecture of the Casas de la Asegurada, their program, spatial organization, and significant architectural components.

The general objective of this text is to show the state of the art of the Casas de la Asegurada built in Mexico City and to achieve this, two specific purposes were defined: (1) to compile the largest number of primary sources on the subject and classify them, identifying information gaps and (2) to explain the operation of the Casa de la Asegurada through its objectives, the performed activities, and its evolution over time, so that the information compiled in the first purpose is analyzed with an urbanistic, architectural, and gender approach. The aim of the above is to emphasize the importance of this community facility within the collective housing complexes.

2. Methods

This part of the work was a documentary-based approach, divided into two steps: archival research and bibliographic research.

For the archival research, three venues have been consulted: the library of The Interamerican Center of Social Security Studies (CIESS), the Alejandro Prieto Posadas Fund (FAPP), and the photographic archives of the media library of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH).

For the bibliographic research, five databases were considered: Google Scholar (for a first approach to the subject), Scimago, SCOPUS, JSTOR, and the IMSS search engine (for the location of more specific historical material). These databases helped to locate 23 documents strictly related to the subject, as can be seen in

Table 1.

Once the available documents were classified, it was possible to establish the work development based on three scales: the program scale, which allows the study of the Casa de la Asegurada program, including its historic evolution and its objectives; the facilities scale, which allowed the study of the Casas location, operation, and the activities that took place in them; and the case study scale, which allowed the analysis of the urban and architectural features based on the redraw of the blueprints and images found in the archives. For the latter, given the available information, the Casa de la Asegurada located in the Unidad Habitacional Independencia (Mexico City, Mexico) was chosen. This way, it was possible to analyze the importance that this facility had in the lives of the insured women residents in one of the most important housing complexes of Mexico City.

3. Data

First, texts found in the three consulted archives will be described. In the library of the CIESS, five monographic documents on the subject, published in 1956, 1958, and 1959, respectively, were found. Such documents are fundamental for the first general approach of the research project (

Figure 1).

In the FAPP, found at the Institute of Aesthetic Investigations of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), the following files were consulted: 3.3.3.15.5—Casa de la Asegurada Unidad Independencia; 250—Centro de bienestar social en Legaria DF; 252—Anteproyecto de la Casa de la Asegurada en Nicolás San Juan y Xola; 253—Maqueta—Casa de la Asegurada [sic] en Xola y Nicolás Sn. Juan; 265—Centro de bienestar social en Calz. de Guadalupe; 266—IMSS—Casa de la Asegurada Calz. de Guadalupe; 267—Casa Asegurada—Auditorium Casa de Maqs.; 272—Centro de seguridad social; and 293—Casa de la Asegurada Unidad sur. Inside these files, the original plans of the Casas de la Asegurada were found and used for the development of the third general approach of the research project.

In the media library of the INAH, the photographic archives of Bonifacio Maravales, Colección Revista Hoy, Nacho Lopez, and Casasola, were revised. The last two were key to understanding the daily life and activities performed at the Casas de la Asegurada of Mexico City.

Currently, the study is limited to the primary sources located in the archives described above. However, it is considered fundamental, for the archival research finalization, to consult the following facilities: the photographic records of the Social Security and Health Centers built in Mexico City, which are located in the CFE (Federal Electricity Comission)Adolfo López Mateos Historical Archive and that will help to better understand the activities that were carried out in these facilities, as well as its decoration and furniture, which, in most cases, are still in place; the archive of the photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo, who was involved in the photographs of IMSS cultural activities carried out at the Casas de la Asegurada; and finally, the Ignacio García Téllez Single Center of Information (CUI)—IMSS Historical Archive, to revise the 1956–1976 press archive related to the IMSS.

A total of 32 documents –including books, pamphlets, journals, and theses related to the subject were located (

Table 1). Of these, 22 study the origin and development of the IMSS and refer to the social benefits that the institution provides to its workers, including the activities carried out in the Casas de la Asegurada. [

6,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

21,

22,

23,

24,

28,

29,

31,

35,

37,

40]; eight focus on artistic activities developed in the Casas de la Asegurada (mainly dance and theater). [

25,

27,

30,

32,

34,

36,

38,

39], and only three documents briefly analyze the architecture and urban impact of the Casas de la Asegurada [

22,

26,

33] without content influential enough for this work. Finally, four of these 32 publications are of particular interest for this research: [

16], which is an organizational manual for the IMSS Housing units that takes Unidad Habitacional Independencia as a reference and breaks down the activities of the Casa de la Asegurada; [

11] and [

10], which explain the cultural, social, and artistic activities of the Casa de la Asegurada, the first one in written form and the second one through the photographs of Nacho López; and [

12], which consists of the rules of the Casas. Despite their relevance, these four publications only focus on the operation of the Casas de la Asegurada.

4. Historical Evolution of the Casas de la Asegurada

The historical evolution of the Casas de la Asegurada is closely linked to presidential and political agendas, the evolution of the IMSS, and changes in labor legislation, as shown below (

Figure 2).

The IMSS was founded in Mexico in 1943. In this year, 48% of the country’s population was illiterate. As a result, the IMSS and the National Union of Social Security Workers created the Pro-Literacy Centers in 1945 to support the literacy campaign promoted by President Manuel Avila Camacho’s government, building about 400 centers. Between 1949 and 1950, these centers became the Popular Education and Social Security Centers (CEPSS), retaining only 37 of the 400 initially opened [

31] and [

32].

It was not until 1952 that a great change for Mexican women took place. Upon taking office as President of Mexico, Adolfo Ruiz Cortines announced that he would promote the pertinent legal reforms that allowed women to enjoy the same political rights as men. This policy in favor of women’s vote was approved on 17 October 1953 and culminated in 1956 with the opening of the first Casa de la Asegurada.

Before these events, in 1954, the CEPSS began to offer maternal and child education and a first aid program which, in 1955, was transferred to the Institute’s Medical Units due to the increasing number of women. As a result of this program, female beneficiaries began to be trained on dressmaking and toy-making activities in the waiting areas of the clinics and later organized themselves into the Clubes de la Asegurada [

31].

The Clubes de la Asegurada (Insured Women’s Clubs) were comprised of women over 16 years of age who were insured or IMSS beneficiaries and who expressed, in writing, their willingness to belong to the Club [

9]. The purposes of the Clubes were to help the economic, spiritual, and social liberation of women, especially through education and use of all the resources and elements available to meet the most pressing needs of the family; to maintain the principle that the functions of wife and mother are best fulfilled when the woman has the proper preparation and house to create a home, where her children are well-nourished, clothed, healthy, with schooling, and an assured future; to take due advantage of the unoccupied moments of women in constructive and educational activities which, far from taking them away from the fulfillment of their domestic obligations and their high moral purposes within the family and the community, make them more dignified and respectable; and to procure the attainment and preservation of health through an appropriate medical-hygienic and sanitary orientation [

9].

As demand for the courses offered in the Clubes grew, their activities began to invade the clinics, preventing them from functioning properly and provoking the disagreement of the directors of the medical units.

Simultaneously, the first Feminist Congress took place in Merida, Yucatan, on January 13–16, 1956. In this congress, it was recognized that women are not free concerning their guardianship and are only devoted to their home, fulfilling their role as wife and mother, which is why education is required to allow them to live independently and to seek an honest subsistence. To address this, it was proposed that in all centers of culture women should be informed of the power and variety of faculties and repercussions formerly performed by men, which would allow them to earn a living if necessary. Thus, this act marked the beginning of women’s participation in the economic, social, and political life of Mexico [

18]. Likewise, this congress recognized the main activities in which women should be educated—painting, sculpture, decoration, silversmithing, printing, bookbinding, lithography, photoengraving, steel and copper engraving, florist, ceramics, hygiene, medicine, pharmacy, and literature—becoming a great inspiration for the structuring of the programs of the Casas de la Asegurada [

18].

The ideas proposed in the Congress, together with the invasion of the medical units, led Antonio Ortiz Mena, director of the IMSS, to create the Casas de la Asegurada so that women would have a place to meet and receive training. Thus, on 19 January 1956, the establishment of the Casas de la Asegurada was announced, which were meant for women to be instructed, trained, and acquire basic knowledge of hygiene, first aid, and even “morals and good manners” [

31]. Therefore, a Casa de la Asegurada was opened in each IMSS clinic whenever its possibilities allowed it [

32].

The first Casa de la Asegurada was inaugurated on January 27, 1956, in San Bartolo Naucalpan, and the second, in February of the same year in Tizapan [

32]. Gradually, others were established according to the number of existing Clubes in the area, being the places where activities took place. Once installed, the Cultural Action Office of the Press, Publicity, and Social Action Department provided them with technical and administrative personnel, as well as furniture and equipment necessary for the development of activities [

12].

By the end of 1956, 14 Casas de la Asegurada were operating in Mexico City, Jalisco, Veracruz, and Sonora, offering courses in literacy, cultural subjects, medical and hygiene education, health orientation, mother and child education, hygiene and safety at work, first aid, journalism, dressmaking, knitting, toys and decoration, cooking and dietetics, beauty culture, puppet theater, dramatic arts, modern and regional dance, music, and physical education [

31].

At the end of 1957 and the beginning of 1958, the Centros de Extensión de Conocimientos (Knowledge Extension Centers) were created. These were installed in private homes, school classrooms, housing units, factories, etc., to complement the programs of the Casas de la Asegurada, benefiting uninsured women [

18].

At the end of the six-year term of president Adolfo Ruiz Cortines, the IMSS reported the following facilities founded throughout the country: 73 Casas de la Asegurada, which served 107,000 women; 364 Clubes de la Asegurada; and 23 Centros de Extensión de Conocimientos for the uninsured [

25]. At the end of 1959, the IMSS had 13 Casas de la Asegurada in Mexico City (

Table 2), located as shown in

Figure 3.

In 1960, the name Casas de la Asegurada was changed to Centros de Seguridad Social y Bienestar Familiar (Social Security and Family Welfare Centers) under the idea that the family is the social institution par excellence, preparing the individual based on his or her social responsibilities. In this way, formative spaces would be provided to the family members of the beneficiaries without exclusivity to women [

31]. Support for women continued, but the focus shifted to the family, which is considered fundamental to ensure that each member of the family achieves individual wellbeing. The change of name would also affect the programs offered and reduce the space gained by women at many levels within the public sphere, politics, budgets, their own homes, and even the organization of housing units.

By that time, there were 58 centers throughout the country, where activities were grouped into programs of healthcare (for disease prevention, personal and collective hygiene, maternal and child hygiene, and environmental sanitation), family household activities (to improve homes in terms of space, nutrition, clothing, and wage protection), and cultural initiation activities (focused on literacy, regularization of elementary school studies, and guidance on family issues and knowledge of the law) [

31]. Likewise, activities were promoted for young people who were promised the construction of more adequate facilities, which provided great material work that configured the basic infrastructure of the IMSS in force to date, and whose architecture is described in

Section 6 “First reflections on the architecture of the Casas de la Asegurada” on this work.

Giving all of the above, it is worth highlighting the importance of these facilities in their insertion and social impact within the large developments of low-income housing in Mexico City, such as the Unidad Santa Fe (Unidad Santa Fe Housing Unit) of Mario Pani and Salvador Ortega’s team, the Unidad Independencia of Alejandro Prieto and José María Gutiérrez team, and the Unidad Morelos of Guillermo Rossell de la Lama’s team, among others.

By 1964, there were 79 Centros de Seguridad Social y Bienestar Familiar (CSSBFs) in the country [

31], and by 1971, there were 15 in Mexico City, as can be seen in

Table 3 and located as shown in

Figure 4.

Finally, in 1978, the CSSBFs were renamed Centros de Seguridad Social y Capacitación Técnica (Social Security and Technical Training Centers), due to changes in the Federal Labor Law that established the right of workers to training [

31].

It is important to point out that, currently, many of the centers have changed their programs according to the IMSS requirements, but they continue to be called Casas de la Asegurada, especially by their beneficiaries who, in many cases, use it as a symbol of resistance and empowerment.

5. Objectives of the Casas de la Asegurada

The journey of the Casas de la Asegurada begins supported by the words of Antonio Ortiz Mena, IMSS General Manager, who, in November 1956, stated that Mexican women should face Mexico’s problems, be socially and politically active at all times, and be an “intelligent and enlightened” factor to intervene constructively in the resolution of these problems [

32]. The Casas de la Asegurada are, therefore, the beginning of the empowerment of women in Mexico.

Based on these words, the following are some of the objectives that appear in the documentation provided by the IMSS around the Casas de la Asegurada and that, in some cases, are contradictory to each other, oscillating, as Solis Hernandez and Silva Acosta [

37] indicate, between the image of the submissive woman and the subtle worker.

According to the Regulations of the Casa de la Asegurada issued by the IMSS, the purpose of the Casas was to help the economic, spiritual, and social liberation of Mexican women and the preservation of health in the household through adequate forms of social security, such as preventive medicine, recreation, and education [

11]. The Casas de la Asegurada sought to support women by giving them training courses and providing them with services on the mentioned topics so that they could obtain a basic integral education with the purpose that Mexican workers could improve their standard of living and have better preparation for their daily struggles [

25].

It was in the Casas de la Asegurada that popular out-of-school education, a non-formal education that concluded without recognized degrees, was first tested. No diplomas were issued through this system for two reasons: first, because being centers strictly for the promotion of social security, they were characterized as only being promoters of the improvement of the living standards of their members, thus removing the IMSS from the obligation to certify any professional practice [

11], and second, because according to the Program of Activities of the Casas de la Asegurada elaborated by the IMSS, working women and beneficiaries had little time to receive more extensive courses, and it was not desired to disassociate them from their domestic activities and their role as managers of the household, but instead, to strengthen them in this sign of femineity [

11]. This last reason was contradictory to what was proposed by the 1956 Yucatan Feminist Congress and was limiting towards the previously stated goal of liberating Mexican women economically, spiritually, and socially.

Another objective of the Casas de la Asegurada was to promote social service as an organized activity among its beneficiaries. Through this, women could better fulfill their mission in society, adopting a better way of life, organizing themselves as a community, participating in relations with society, and integrating themselves into its changes and progress [

18]. It also emphasized the solidarity and social cooperation of Mexican women among themselves to achieve their social security (for example, through food pantries or collective discounts) and the solution of domestic and community problems [

12].

6. Operation and Activities of the Casas de la Asegurada

Regarding their operation, the Casas were managed following the Regulations of the Casa de la Asegurada established by the IMSS. They depended, in terms of technical, teaching, and administrative management, on the Cultural Action Office of the Press, Publicity, and Social Action Department. This office assigned the personnel to each Casa, consisting of an administrator, a social worker, an administrative secretary, an administrative assistant, an educator, a babysitter, a housekeeper, a guard, and a porter [

12].

The Casas de la Asegurada only served members and beneficiaries enrolled in the Clubes. Therefore, they could not be used for activities outside the Clubes nor used for events that were not included in their activities. To register, women had to submit three photographs, present their insurance of beneficiary credentials, be over 15 years old, and have their homes located within the area of influence of the Casa they wished to join [

32].

To attend the courses, which were free of charge, the beneficiaries were organized in groups, two or three per semester, which grew to over 30 students. As for the organization of the courses, they were arranged in such a way that several groups could study the same subject at the same time. Each subject was taught for three, four, or six months so that the beneficiaries could study two or three subjects at the same time, completing eight of them after one year [

32].

The program of the Casas de la Asegurada outlined by the IMSS (

Figure 5) divided the activities into three categories: cultural, social, and artistic. Within these, different educational approaches were considered: aesthetic education, with activities such as dance (regional, classical and modern), physical education, and beauty culture; medical education, with activities in first aid, medical-hygiene education, health education, mother-child education, and hygiene and safety at work; civic and cultural education, with cultural subjects of history (national and universal), civics, science, geography, home economics, music (children’s and adult choirs and musical culture), drama, puppetry, cultural initiation (literacy courses), and journalism; and education for home improvement, clothing, and food, where cooking, dietetics, confectionery, baking, cutting and sewing, hand and machine weaving, machine embroidery, toys, decoration, and family training were taught [

11].

In addition to the previously mentioned activities, the Casas de la Asegurada offered numerous services that complemented the educational offerings and were coordinated between the IMSS social workers and the Clubes de la Asegurada. These included a children’s room, library, music room, discotheque, newspaper library, film library, art room, special events (such as exhibitions, lectures, and competitions on domestic arts), civic, cultural, and recreational events, festivals, popular and classical music concerts, modern and popular dance exhibitions, theatrical shows, excursions, labor exchange and mutual aid, organization of consumer and production cooperatives, family food pantries, legal advice on social security, individual and collective civil marriages, legalization of marital unions, and regularization of the family’s civil status, among others [

12] and [

11]. To develop these services and the aforementioned activities, each Casa de la Asegurada was required to be equipped with the areas indicated in

Table 4.

As for the organized social service, the IMSS launched a “brigade system,” planned by the Casas de la Asegurada and the preventive medicine area of each clinic. These brigades were composed of interdisciplinary groups with expertise in medicine, dentistry, nursing, and environmental sanitation. The IMSS launched two campaigns: hygiene and home economics. These included itinerant activities of a preventive and assistance nature to reduce unhealthiness, ignorance, and poor living conditions of the general population with the ultimate goal of reducing mortality [

32].

7. First Reflections on the Architecture of the Casas de la Asegurada

The Casas de la Asegurada are part of the so-called Mexican Social Security Architecture. A functionalist architecture that responded to the needs and protective vision of social welfare that the State had at that time. Its language corresponds to the International Style, standardized and compact, where the image, character, and repetition of the buildings, as well as the scale of the urban complexes convey the idea of monumentality. Each project takes into account the local conditions, responds strictly to the architectural programs demanded, and adapts in the most austere way to the climatic conditions of each site [

20] and [

26].

During the administration of President Adolfo López Mateos, a major construction plan for medical, social, and administrative units was implemented to provide the IMSS adequate buildings to cover the provision of social security and welfare services throughout Mexico City and the rest of the country (

Figure 6).

The core team in charge of devising these facilities was integrated by Carlos B. Zetina, Alberto Castro Montiel, Guillermo Carrillo A., Jorge Creel de la Barra, Agustín Chávez, Gilberto Flores, Federico González Gortázar, Teodoro González de León, Eduardo Graue, Leonides Guadarrama, Enrique Guerrero L., César Lagner, M. de León Acevedo, Benjamín Magaña, Manuel Mangino, Eduardo Manzanares, Héctor Mestre, José de Murga, Imanol Ordorika, Salvador Ortega, Guillermo Ortiz Flores, Joaquín Pantoja, Leonel Pérez Villegas, Aarón R. Bolaños, Roberto Rojas Argüelles, Joaquín Sánchez Hidalgo, Manuel San Román, Manuel de Santiago, Fernando Sepúlveda, Carlos Villaseñor, Enrique Yáñez, and Luis Zedillo [

17] and [

20]. All of them supported by José María Gutiérrez as Deputy Chief of Projects and Construction, building most of the Casas de la Asegurada, Social Security Centers, Theaters, Sports Centers, and Work Training Schools of the IMSS [

29]. At the same time, several of the most outstanding Mexican collective housing architects of the time, such as Mario Pani and Salvador Ortega, as well as Alejandro Prieto and José María Gutiérrez, included Casas de la Asegurada in their large collective housing complexes and were in charge of these projects themselves.

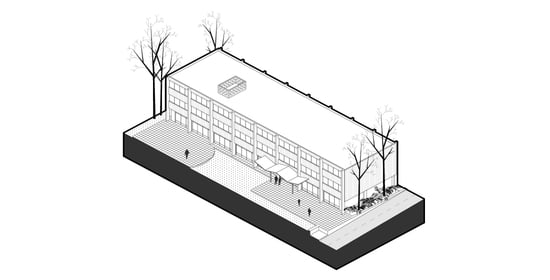

In these large housing complexes, the organizational schemes at the floor plan level respond to the guidelines of early modern functionalism. The buildings have a single use, and the Casas de la Asegurada are independent volumes within the complex, clearly manifesting their program. Such is the case of the Unidad Independencia housing complex, which has been chosen as a case study for a first analysis, both in its urban and architectural scales due to its importance in Mexico City and the amount of information available in the archives consulted.

In this complex, la Casa de la Asegurada, together with the rest of the buildings accommodating complementary programs, are used to articulate the public space creating squares, and serve to weave the new housing proposals with the existing fabric, not only at the spatial realm but also at the social one (

Figure 7).

The Casa de la Asegurada is situated in the area of the housing complex popularly known as Centro Civico. It takes its name from the large square planned for civic purposes located there and is complemented by the theater, basic commodities’ shop, and social building. These buildings, at the same time, form a public open space secondary to the main square, which works as a distributor to access the backstage of the theater, as well as to the pedestrian walkways and driveways of the shop, the Casa, and the social building. The Casa de la Asegurada, along with the social building (whose lobbies are separated by a narrow driveway) and the main street adjacent to the complex, form a triangle with a garden in its interior that, taking advantage of the topography of the site, remains well isolated from the street providing an open and safe site, which is used by the Casa de la Asegurada as a leisure and playground area, directly connected to the children’s program located at the south end of the ground floor, as shown in

Figure 8.

The current state of the building is especially interesting, as the evolution of the complex, the city, and the culture have resulted in it being completely gated, impeding the connection with the neighboring programs and buildings originally planned, and allowing the construction of improvised volumes for the accommodation of complementary programs. At the same time, the landscape has changed, and with the trees fully grown, shade is provided to open spaces and buildings, which are no longer easily perceived from a distance, as can be seen in

Figure 9. Likewise, the social building has completely modified its program, and the IMSS has taken away its original purpose for the housing complex use and turned it into a branch of its nursing schools so that free access for residents is no longer possible.

As for the characteristic architectural components of the Casa de la Asegurada, three elements stand out: the access canopy, the facades freed from structural loads, and the flexibility of the layout (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

In several facilities at the Unidad Independencia housing complex, it is common to find a portico that defines the entrance and endows it with a human scale. The Casa de la Asegurada is no exception. These porticoes are generally covered by pergolas or slabs in which the formal, constructive, and structural explorations, typical of the period, are manifested by complex surfaces, as can be seen in

Figure 9.

With the structural liberation of the facades, the walls become separated from the porticoes, which acquire greater plastic strength. The windows occupy a large part of the façade, allowing greater access of sunlight to the interior, which facilitates the development of the various activities and a greater visual connection with the outdoor public space.

The structural approach of the building consists of concrete columns and slabs forming 5 m modules that allow a very flexible distribution of the program (

Figure 10). On the ground floor, access is possible from both sides in the middle part of the building, entering a hall that connects the stairs and a hallway that leads to both ends of the facility. In the north end, the program related to dance and gymnastics is organized, while the program assigned to childcare activities is located in the south end, directly connected to the playground. Moreover, in the middle part at ground level, the library and the administrative area are found, comprising several offices. The first floor is mainly dedicated to workshops that need fixed installations for their operation, such as embroidery, dressmaking, aesthetics, and cooking and baking. All of them are located at the eastern side of the building with the hallway facing West, restrooms in the north end, and a resting lounge in the south end supplied with a west-facing balcony. Finally, the second floor, dedicated to classrooms, is distributed in the same way as the first floor, with all of them facing east and the hallway and restrooms in the same positions.

Following the precepts of the Modern Movement, it can be observed that the architectural layouts are flexible, allowing great freedom in the internal distribution of activities. In addition, they are efficient in the distribution of the program components, so that horizontal and vertical circulations are reduced, and they have an optimal location of the service areas in relation to the served areas. As for the interior spaces, transition spaces appear repeatedly: on the one hand, between the street and the interior (porticoes, halls, or lobbies) and, on the other hand, between the various areas of each building (large corridors or waiting areas). The standardization of the construction systems used resulted in the creation of an architectural image characteristic of the IMSS Architecture.

It is important to emphasize that, although the participation of women in the activities distributed in the architectural program of the Casas de la Asegurada can be considered as redomestication, as indicated in the introductory reflections of Henderson and Hayden, this also facilitated solidarity, unity, and camaraderie among the participating women, as can be appreciated in

Figure 11. The inclusion of childcare areas and safe spaces for children allowed women to engage in various group activities, generating strong social cohesion. Moreover, the adequate facilities enabled the serious and formal development of these activities, which in some cases were so successful that they allowed the women’s groups to practice them professionally, obtaining remuneration that could lay some foundations towards their economic freedom. Such is the case of the Dance Workshop established in the Casa de la Asegurada of the Unidad Santa Fe housing complex in 1957 which in 1958, became Mexico’s Chamber Ballet. [

32].

8. Conclusions

Through this research, it has been observed that to ensure facilities that promote the empowerment of women in everyday life and gender equity both internationally and in Mexico, it is necessary to design and build new programs and architectural structures that encourage the deconstruction of current gender roles. To this end, the historical exploration of case studies is considered fundamental, as it allows to glimpse successes and errors from the perspective of that historical moment but also from the current moment, understanding that the social construction of gender varies with time, culture, and region, among other aspects.

The Casas de la Asegurada in Mexico can be highly criticized from today’s point of view as they sought to educate women based on post-World War II private women, who were at the service of the household and their families. However, there are some positive lessons to be learned from this program and its facilities. Some of these can be studied from a contemporary perspective and applied as possible tools in the design of future programs.

A review of the activities offered at the Casas de la Asegurada, according to the four spheres of daily life (the productive sphere, the reproductive sphere, the self-sphere, and the political sphere), shows that the activities impact, mainly and to a limited extent, the self-care and reproductive spheres, focused primarily on care (self-care and care for others). This training takes away the freedom of women who have no learning options other than domestic care and economy, not allowing them to grow in other spheres. Nevertheless, this knowledge, centered on the reproductive approach, was skillfully used by Mexican women within the productive sphere to perform care work for third parties, being able to earn income for the household, which, although not contributing to their social liberation, did help them achieve economic freedom.

As for the services provided by the Casas to their beneficiaries, it can be observed that these are focused not only on the personal sphere but also on the political sphere with social activities, civic events, festivals, and above all, the social service with an impact on the community. Thus, these services could compensate for the lack of impact on the social liberation proposed in their activities and further contribute to the spiritual liberation of women initiated in cultural education. Likewise, the Casas de la Asegurada offered various services such as childcare, family food pantries, and mutual aid focused on the reproductive sphere, which not only benefited the daily lives of their users by reducing the time devoted to care but also led to the construction of relationships with other women, creating existential alliances and policies of mutual support and empowerment.

In architectural terms, the Casas de la Asegurada are proper buildings without innovative spatial or material proposals but with impeccable functioning that allows great flexibility in the development of different activities thanks to the standardization and simplicity of the construction. They are optimally adapted to the housing complexes in which they are located, going practically unnoticed. However, it is worth noting the symbolic importance of these buildings for women in public spaces, since they made it possible to change their organization and hierarchy so that women could occupy them as social agents. Today, many of the first users of the Casas de la Asegurada continue to name the buildings this way although they have been renamed over time, as explained in

Section 4. This is because, for them, these houses were a symbol of empowerment, access to public space, a tool for the construction of sisterhoods, and access to other spheres outside the reproductive one. This is why the creation of these facilities dedicated to women is considered essential until they become the accepted rule and not the exception.

This paper shows the state of the art of the Casas de la Asegurada of Mexico City. For this, the greatest number available of primary sources on the topic has been compiled, classifying them, and identifying information gaps, to explain how they work through their objectives, performed activities, and evolution through time. In this assessment, it can be observed that the object of study has been under-analyzed outside the terms of social security and dance, which is why new research with a gender perspective, and under architectural or urbanistic terms, is relevant to extend its understanding, uncovering the importance of the Casas inside the collective housing complexes.

This study’s contribution focuses on the location of the primary sources available on the topic, along with the compilation and organization of historic, statistical, numeric, and qualitative data that help to understand the importance and impact of these tools in the daily lives of Mexican insured women.

The study also helps to open the possibility of a series of future works that could help to better understand, on one hand, the performance of the Casas de la Asegurada within the housing complexes in urbanistic and community living creation terms, and on the other hand, their architecture, spatial organization, and significant architectural components. It is expected that both aspects can be studied, not only under comparative terms between different Casas de la Asegurada founded through time but also throughout the study of specific cases. Regarding the latter, the specific and profound revision of the Centro de Seguridad Social y Bienestar Familiar of Unidad Independencia housing complex is considered essential, as it is the last facility designed as a Casa de la Asegurada in which everything learned since 1956 was crystallized and was founded as a Social Security and Health Center, serving as a base of organization and design for subsequently built centers across the country.