1. Introduction

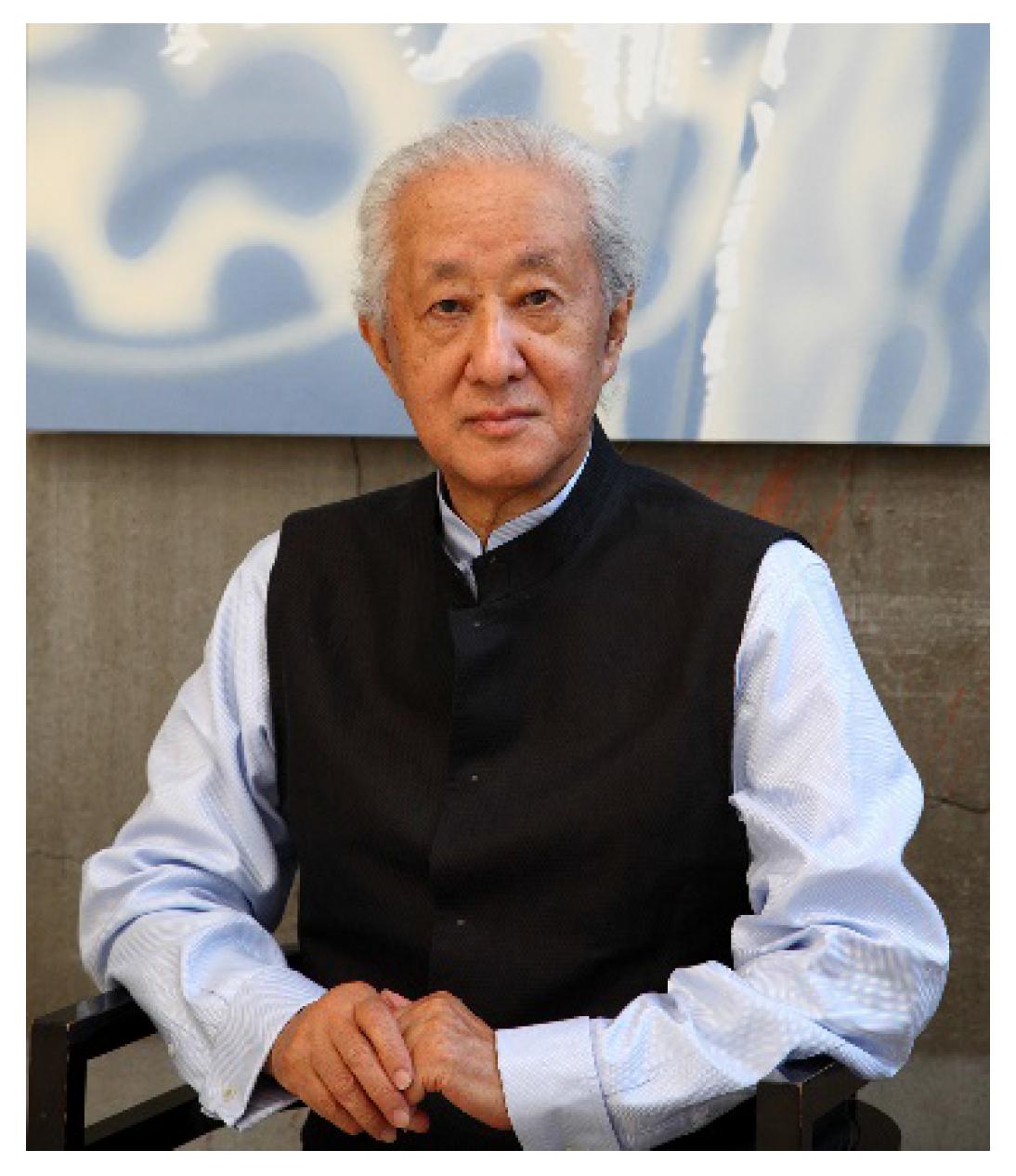

With a very productive career that spanned over six decades, over 100 built works and a heterogeneous oeuvre that is unusually diverse and original, writing about the Japanese architect Arata Isozaki (born 1931 in Oita, South Japan) can be a real challenge. However, now 86 years old and globally admired, Isozaki’s work is due a timely reappraisal, particularly as it has recently been overlooked, for instance, by the Pritzker Prize jury.

In 1990, I left the office of Jim Stirling, where I worked in London, to move to Japan and work as a young architect for Arata Isozaki in Tokyo. I planned to stay in Tokyo to experience working there for a maximum of 12 months and had not anticipated how much this change of workplace and culture would affect my future life and my thinking about architecture. Only later did I realise that the epicentre of world architecture had relocated to Japan and that Tokyo was, at that time, the place to be. In the end, I stayed with Arata Isozaki for three years before moving to Berlin to open my own practice in 1993. My time in Japan gave me a good opportunity to closely observe and study the master’s oeuvre.

My arrival in Japan, having come from Stirling’s office (which was a relatively small firm with ten staff and a limited number of projects), could not have been a more extreme change of pace: Isozaki Atelier, as the office was called, was a buzzing hub with a large number of interesting projects and activities. The atelier was organised with Isozaki as the single master, heading up a group of around 30 devoted architects. Nobody used computers while I was at Stirling’s office; Isozaki Atelier embraced and represented the future of architecture. The digital revolution was happening.

I had encountered Isozaki’s work a few years earlier as a young architecture student when visiting an exhibition in Frankfurt displaying the 1984 competition proposals for the new Museum of Applied Arts; a project which was won by Richard Meier. Isozaki’s design proposal was so different from anything else there: he placed a giant cube in the middle of the parkland, thus minimising the building’s footprint and preserving most of the beautiful park and trees. I also admired his Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles, which opened in 1986, and I had seen photos of the Museum of Modern Art in Gunma (1974), a much-published earlier masterpiece. It was obvious to me that Isozaki was a refined master Architect, working in his own universe.

I came to Tokyo when Isozaki turned sixty and had reached the peak of his career (with branch offices in New York and Barcelona), receiving a growing number of invitations to participate in design competitions, including in Germany and Austria. We collaborated on large-scale design competitions for prominent sites in Berlin (one resulted in the two buildings at Potsdamer Platz, for which we later formed a partnership), in Munich, Stuttgart and Vienna (where we won the first prize for the design of two unbuilt twin towers) and the prestigious Tate Modern design competition in London.

From around the mid-1980s onwards, Isozaki seemed to be building worldwide and was the first Japanese architect to be working globally while, at the same time, intensely busy in his home country: Japan’s post-war economy had been continuously booming since 1960 (a period of rapid economic growth which came to an abrupt end with the ‘bursting of the Japanese economic bubble’ in 1991) and Isozaki was well equipped to take advantage of this boom, getting his most extraordinary and ambitious designs built. His projects were, however, rarely in Tokyo. Most of his buildings are to be found in Japan’s smaller cities, such as in Mito, Kyoto, Nara and Kitakyushu, or dotted around Tokyo’s outskirts. The architecture critic Herbert Muschamp noted in 1993 regarding this era ‘Arata Isozaki came of age in a country that was not only physically and economically in tatters but had also been torn from its cultural moorings.’

2. A Large and Diverse Oeuvre of Buildings, from Playful and Inventive to Monumental

Arata Isozaki graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1954 and went straight to work under Kenzo Tange, the father of post-war Japanese architecture, before establishing his own firm, Isozaki Atelier, in 1963. His early Japanese projects, such as City in the Air (1960–1961) and the Oita Prefectural Library (1962–1966), bear strong influences from Le Corbusier, Louis I. Kahn and Kenzo Tange, Isozaki’s early mentor. Isozaki belongs to the same generation in Japanese architecture as Fumihiko Maki, Kisho Kurokawa, Kiyonori Kikutake and the Metabolist movement. However, while he was sympathetic to their ideas and theories for new forms of cities, he never joined the Metabolist group, preferring rather to follow his own avant-garde path.

It was the beginning of the maturation process of Japanese architecture, which would continue for decades. The widespread devastation of Japanese post-war cities brought an urgent need for new housing, while an economic boom also allowed for architectural experimentation and the realisation of innovative ideas. As a result, Japanese architecture since 1960 has consistently produced some of the most influential and ground-breaking examples of modern design in the world. Over the course of his long career, Isozaki always maintained an interest in visionary forms of cities. In 1960, he created an ironic photomontage with the title ‘Future City’, in which he placed a Metabolist mega-structure within a field of classical ruins. Regarding this montage, Schalk notes that “the image pictures the city as the place where many life-cycles of various cultures rise, overlap, and decline. In this juxtaposition of the already declined (Western classical architecture) with the visionary (Japanese Metabolist architecture) and its future (parts of the new scheme already collapsed), historical time appears compressed” (

Schalk 2014, p. 281). In the end, very little of these visionary theories crossed over into reality and, ironically, one of the few Metabolist projects ever built was Isozaki’s Prefectural Library in Oita (1966).

What are Arata Isozaki’s influences? Isozaki has a deep understanding of architectural history, which allows him to easily create direct links between his designs and the past. His interest and expert knowledge of Renaissance and Classical architects, such as Borromini or Schinkel, and his vast knowledge of architectural theory allowed him to use a variety of historical references without restraints. Isozaki draws on a dazzling range of influences (

Taylor 1976). His thoughts and approach to architecture are profoundly influenced by different key experiences and he has extensively commented on these influences: first and foremost, the Emperor’s Katsura Villa, the architectural masterpiece in Kyoto: an idealised example of a circulation around a system of garden spaces as described by Junichiro Tanizaki and Bruno Taut (

Tanizaki 1977;

Isozaki 2005). But there were also the images of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, which Isozaki saw as a young man. His major artistic influences include the Japanese space/time concept of ‘Ma’, a concept Isozaki repeatedly attempted to express in exhibitions. He is also influenced by Surrealism, Constantin Brancusi’s idea of the

Infinite Column and the sculptural work of Isamu Noguchi, as well as the architectural work of Louis I. Kahn, especially his use of the barrel vault at the Kimbell Art Museum and the unbuilt City Tower project for Philadelphia. Similar to the work of Kahn, Isozaki shared a preoccupation with monumental and heavy buildings that did not hide their weight, materials and rough surfaces. Isozaki frequently referred to the Salk Institute in La Jolla (1959–1965), one of Kahn’s masterpieces in which he composed a campus and courtyard overlooking the ocean and enclosing a heroic water garden; a space that offers the sensation of being both inside and outside at the same time, a space we can find again and again in Isozaki’s work (

Stewart 1991, p. 53). He has written extensively about all of these influences and what they have meant for him, as well as the intriguing capacity of Modernism to translate all kinds of artistic and urban qualities into a new language.

Considering his writing about the production of new urban constellations, Isozaki refers to earlier urban ideals, such as Wright’s

Broadacre City, Le Corbusier’s

Radiant City and Ungers’ and Koolhaas’

Archipelago City. He also understands architecture as an inherently urban discipline. If one thing sticks out, it is Isozaki’s interdisciplinary approach: the ease with which he moved between urban design, fashion design, graphics, furniture and stage design, which influenced his ideas far beyond the field of architecture (

Isozaki 1998,

2006).

I was always stunned by the unprecedented degree of powerful but geometrically simple forms and formal repertoire in his work. He displayed a unique capacity for strong figure-ground compositions which declared architecture to be a compositional art, a celebration of formal expression and a reminder of the urban possibilities large buildings could offer. He frequently spoke about “buildings composed like paintings” and the collages of Juan Gris. He has demonstrated that architecture is something to be composed, elaborated on and celebrated, with unique ideas of space which are then turned into a special atmosphere, generated by elegant theatrical spaces and extraordinary stage-like settings. With close attention to proportion, his conceptual originality for powerful designs would asymmetrically join strong geometric forms, such as juxtaposing a cylinder with an exact cube and a half-cylinder, which were combined with an exquisite refinement and complexity of detail. The level of attention devoted to every detail, the willingness to search everywhere for the ‘perfect’ materials and the obstacles overcome to achieve perfection—all of these are the hallmarks of Isozaki’s working method and his devotion to perfection.

The idea of composing buildings as pure objects rather than socially engaged architecture is persuasive because it is, in fact, exactly how they appear to the visitor and user. While his compositions were shaped by simple and visually calm forms—giant prism-shaped gallery spaces and spherical or pyramid-shaped parts arranged with great order, like children’s building blocks, across a site (such as in Los Angeles or Mito)—Isozaki’s capacity to invent new forms was remarkable. These compositions are not anti-functional but are able to resolve the problem of a floor plan while simultaneously creating interesting solutions in section and elevation. Just like Bernini and Borromini before him at the beginning of the Baroque era, he has always challenged the boundary between sculpture and architecture. Regarding this, Joseph Giovannini (

Giovannini 1986, p. 3) wrote: “Not since the French architectural visionaries of the 18th century has an architect used solid geometric volumes with such clarity and purity, and never with his sense of playfulness.”

The interiors of Isozaki’s concert halls and cultural buildings are equally striking: here he frequently used optical illusion, with curved or mirrored glass and printed patterns on glass, creating enigmatic optical distortion, ensuring a full sensory experience in the elegant entry foyers (from Tsukuba Center Building to the Kyoto Concert Hall).

3. The Triumvirate of Post-Modernism: Isozaki–Hollein–Stirling

Beside all of his monumental playfulness, symbolic messages and post-modern freedom, Isozaki was also a romantic architect rooted in history: a tendency that could generally be seen in the work of Arata Isozaki, Hans Hollein (1934–2014) and James Stirling (1926–1992) around this time and which would later be termed ‘Post-modernism’. For instance, the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, a masterpiece with a fondness for allusions to the stage by James Stirling (1977–1984), and Hans Hollein’s Museum Abteiberg (1972–1982) were not unlike Isozaki’s newly-built ruin of the Tsukuba Center: a new civic centre built around the same time (1979–1983), referencing architectural history and consisting of cubist-like compositions of memorable fragments: a collage of eclectic references ranging from Michelangelo to Borromini, Piranesi and Ledoux, all composed in perfect synthesis in an ‘eclectic ruin of the future’. Importantly, his referencing of historical themes and fragments, narrative content and its figuration did not occur at the expense of the usability of these radical buildings, nor was it superficially attached, but well integrated: the functional organisation of his geometrical compositions was marvellous. At this point in time, in the early 1980s, the three buildings by Isozaki–Hollein–Stirling signalled a clear and radical break with a tired and austere International Modernism and its shortcomings.

Isozaki and Stirling had begun their careers with classical modern buildings before starting afresh and subverting the compositional and theoretical ideas behind the Modern Movement. In 1978, Colin Rowe suggested in ‘Collage City’ that Modernism is not simply Functionalism but may also draw on history. According to Rowe, it was not only acceptable that Modernism would quote from the rich history of architecture but that Modernism could be at its best when directly referring to history. He argued that in a Post-Modern reaction to Modernism’s ‘total-design’ approach, urban design must be considered through “fragmentation, bricolage and metamorphoses of interpretations” (

Rowe and Koetter 1978, p. 23). This was a completely new reading of Modernism, which had gradually manoeuvred itself into a dead-end. Today, the completion of these three radical buildings is considered by many historians to be a watershed moment in 20th century post-war architecture. Isozaki realised the relevance of his earlier provocative collage, re-exhibiting his 1968 ‘Re-ruined Hiroshima’ photomural at the Japanese Pavilion at the 1996 Venice Architecture Biennale (

Ku 2011;

Weiss 2013).

Japanese architecture has a long tradition of borrowing from foreign cultures (first from China, then from the West) and much of Japanese design comes from a process of borrowing, transforming and refining. Isozaki sees himself as nothing less than a key protagonist and player in the history of the discipline of architecture, in line with the self-conscious innovator Le Corbusier and with Louis I. Kahn, who also insisted on architecture as an art form. He has displayed a strong understanding that the design of buildings is a serious intellectual business and frequently relates his own architecture to the works of the Renaissance masters, such as Michelangelo (

Drew 1982;

Futagawa 1983). His long friendship with Hans Hollein and enormous respect for James Stirling’s work allowed a shift of focus away from purely Japanese topics at the time. The team of Isozaki–Hollein–Stirling was to become the “Triumvirate of Post-modernism” (

Jencks 1984) and they soon emerged as the leading architects responsible for most new museums and art galleries during the 1980s. The three became the key figures representing the most significant trends within architecture at that time and Isozaki’s global activity made him one of the first ‘star-architects’ and a true global citizen (a long time before the negative connotations now associated with the term ’star-architect’, Isozaki embodied the master that holds total control over his projects). Today, the concept of ‘star-architect’ has lost its relevance and young architects are searching for alternative working methods that effect change through the empowerment of others. 1980 was, however, the beginning of trend-setting and celebrity culture in architecture. As a result of the international nature of his work, Isozaki was frequently called ‘non-Japanese’ and a foreigner by his more conservative Japanese colleagues (

Muschamp 1993;

GA Document 2004).

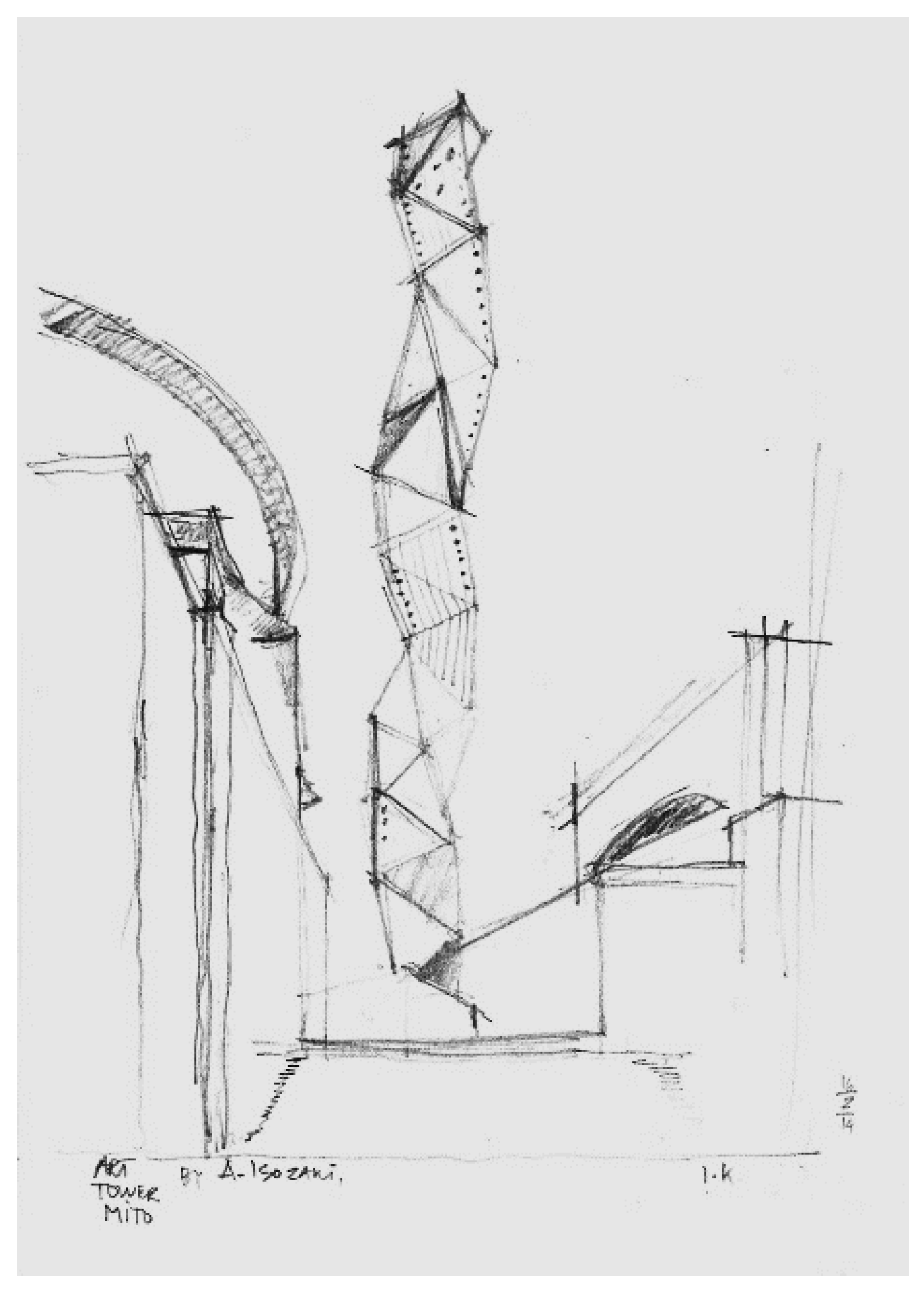

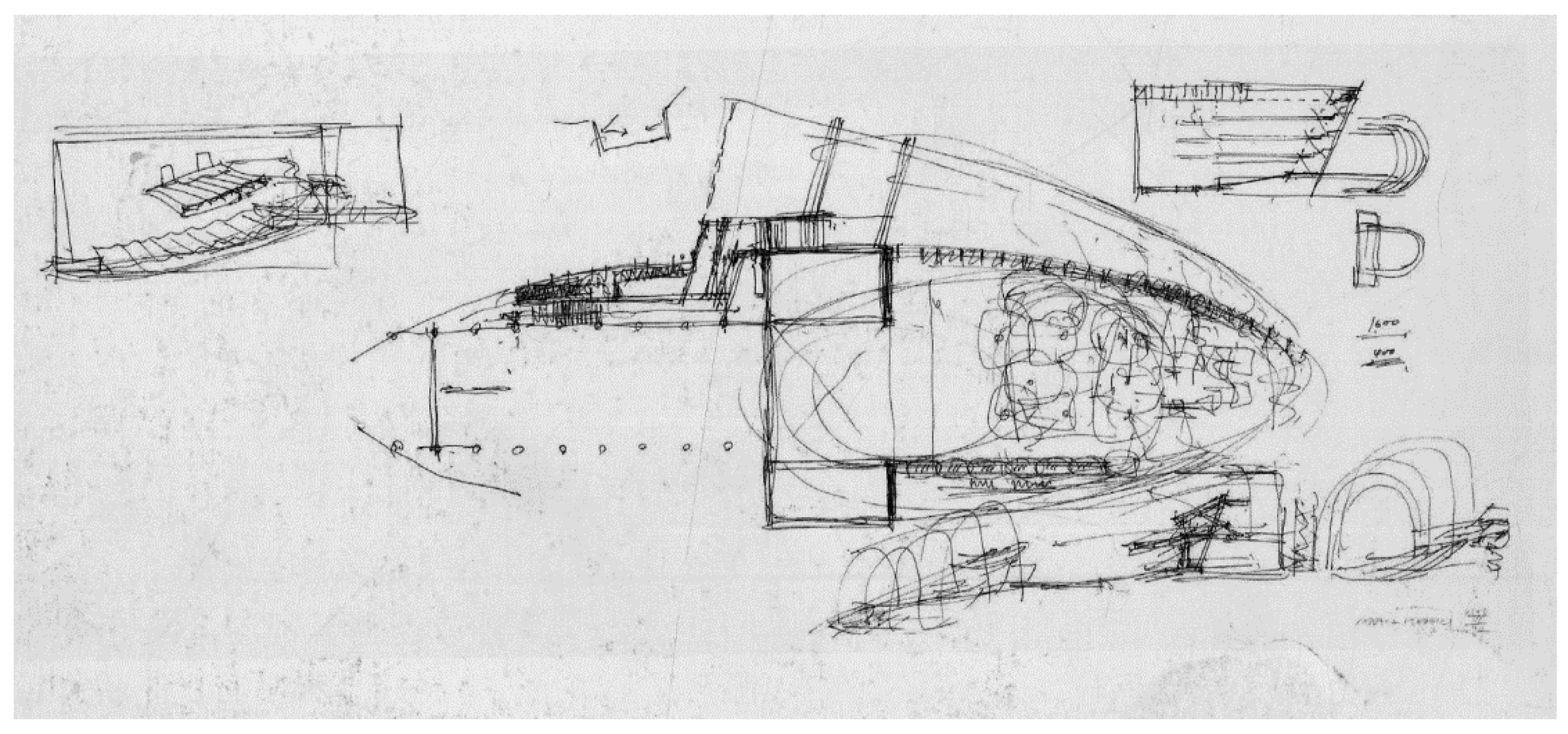

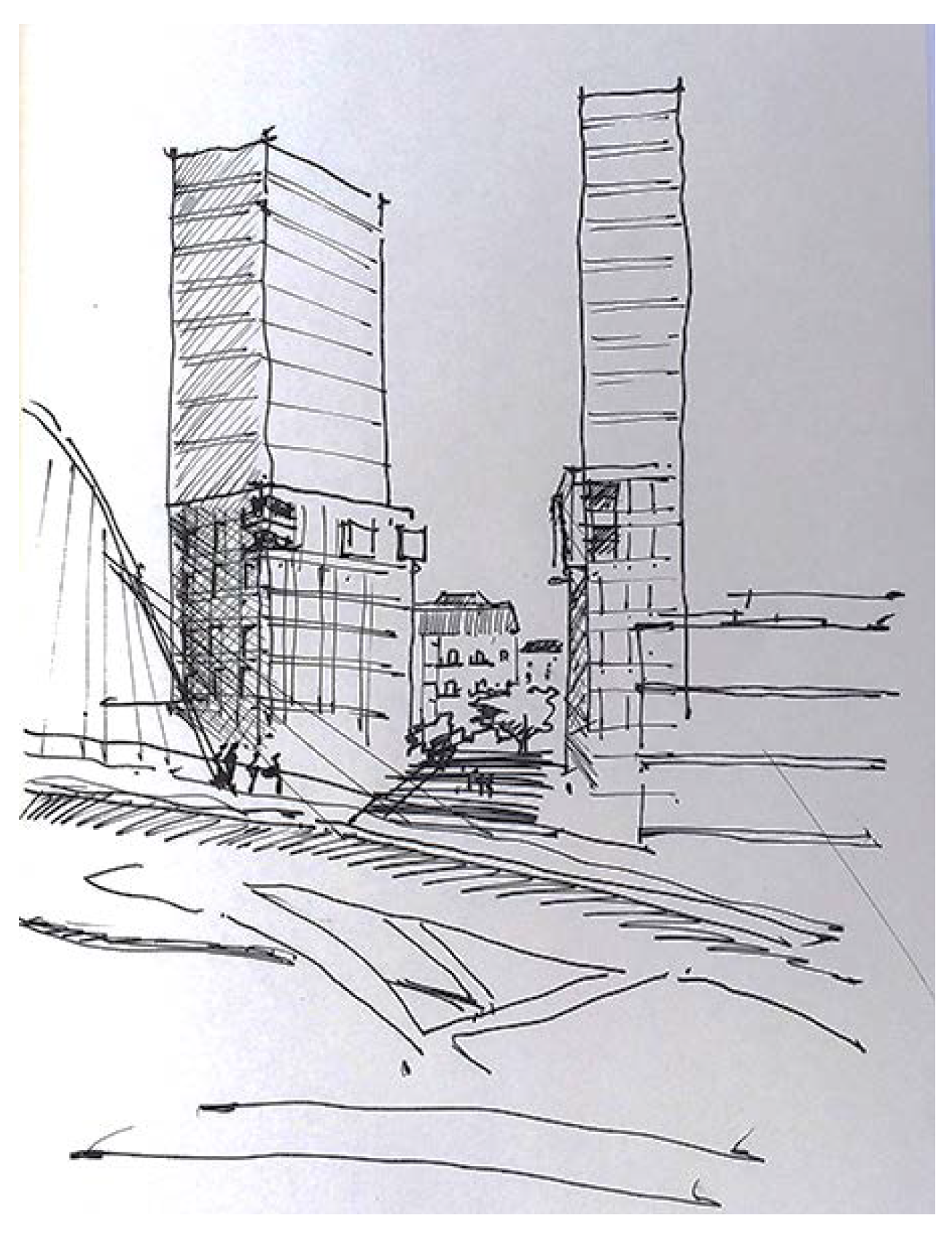

During the 1990s, the Isozaki Atelier had again become a busy place with commissions arriving from all over the world; about 15 projects were on the drawing boards or under construction at any given time. In addition, much of the extra work was for large-scale design competitions and curatorial works, such as exhibition designs or stage designs. A creative force and an intuitive genius, Isozaki has always been a soft-spoken, charismatic figure, always charming and gentlemanly polite, despite the pressures of the construction business, as well as being very talented: he is able to visualise his ideas convincingly with beautiful hand-drawn sketches that have become collectors’ items. Meetings about projects usually followed a strict ritual in which Isozaki would sit on one side of the large table, without much talking, spending most of the time sketching with ink pen on yellow tracing paper. Regularity and irregularity were reoccurring themes when it came to sketching interiors. Stacks of exquisite drawings, often abstract, elegant hand sketches and diagrams, were produced in long meetings in which he would work ideas over and over, testing different solutions, and it was usually our task to ‘translate’ those freehand drawings into more concrete line drawings that could become a later basis for construction. The following

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show a selection of hand sketches of Arata Isozaki: made on thin tracing paper, these are exquisitely atmospheric and expressive.

4. Four Distinctive Phases in the Work of Isozaki, Spanning Six Decades

Today, Isozaki can look back on a long, diverse and productive career spanning six decades, during which he re-invented himself every 10 to 12 years (not unlike Le Corbusier). With immense discipline and a strong work ethic, Isozaki was able to complete an astonishing number of projects and an almost unbelievable number of design proposals spread over five continents (see also Arata Isozaki’s web site for more information:

www.isozaki.co.jp). An architect as much as an urban designer, with many innovative large-scale urban proposals to his name, the challenge for any interpretation of Isozaki’s diverse body of work is that he refused to restrict himself to any single signature style (unlike Frank Gehry or Richard Meier, for instance, he resisted a singular stylistic brand).

I suggest that one can separate Isozaki’s oeuvre into four distinctively different phases, each of them wholly original:

4.1. Phase I: 1959–1973: Post-Structuralism

His early projects were in Japan, such as commissions in his home town of Oita in South Japan, outside Tokyo. He was at this time heavily influenced by European experiences with a style mixing ‘New Brutalism’ and ‘Metabolist Architecture’, such as the radical Oita Medical Hall (1959–1960), as written about by Reyner Banham (

Banham 1976). These buildings made a feature of their rough concrete structure and looked like machines; an architecture of systems and components which revealed how they were made and assembled. The elegant Gunma Art Museum (1974), Isozaki’s most notable early project, gained international attention and confirmed him as an original force, making a place for himself on the global circuit. His ideas about urban mega-structures (especially ‘City in the Sky’) with their references to organic biological growth and biological processes were similar to the theoretical propositions of the Metabolism manifesto (published in 1960). These hypothetical projects ranged from floating cities on the oceans or on reclaimed land (for instance, work which Isozaki was involved in with Kenzo Tange, such as the Tokyo Bay Plan, 1960) to modular plug-in capsule towers that could incorporate organic growth (similar to Archigram’s Walking City and Plug-in City, 1964; or Yona Friedman’s Spatial City, 1963). The 1968 Electric Labyrinth installation portrayed a ‘Re-ruined Hiroshima’ at the Milan Triennale. His formal approach continued to evolve with buildings such as the Fujimi Country Club (1973–1974) and Kitakyushu Central Library (1973–1974).

Isozaki commented that this phase of technological optimism came to an end with Tokyo’s ‘failed’ EXPO 1970 and the world energy crisis. He would always respond to significant changes in the world’s situation with an equally significant shift in his approach to design.

Typical works from this phase include:

City in the Air (1960–1961, unbuilt), Tokyo, Japan.

Ōita Prefectural Library (1962–1966), Ōita, Japan.

Nakayama House (1964), Ōita, Japan.

Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art (1972–1974), Fukuoka, Japan.

KitaKyushu Central Library (1973–1974), Fukuoka, Japan.

Gunma Museum of Modern Art (1971–1974; refurbishment 2006–2008), Gunma, Japan.

Fujimi Country Clubhouse (1973–1974), Ōita, Japan.

4.2. Phase II: 1974–1989: High Post-Modernism: The Symbolic, Iconic and Ironic in Architecture

During his second phase, Isozaki made such a dramatic impact on the international architecture world that Charles Jencks wrote: “Isozaki has taken the Post-Modernism of the West one step further” (

Jencks 1984, p. 236). His designs became more inventive with geometry, at a time when architecture had to radically reinvent itself. Trust in technology had waned and the oil crisis showed limits to growth. His new approach to design emerged as a reaction against the perceived shortcomings of the 1960s and 1970s, with its lack of reference to the history of architecture and ignorance of local culture. Isozaki frequently worked closely alongside his third wife, the Japanese sculptor Aiko Miyawaki (1929-2014). Pioneering Japanese architecture overseas during this phase, Isozaki was able to realise a series of key projects in the USA, including MOCA in Los Angeles and Team Disney, both of which were important buildings that introduced him to the US. MOCA is still considered to be one of Isozaki’s masterworks: visitors to MOCA enter through a sunken courtyard that is reminiscent of the Tsukuba Center in Japan. The Team Disney headquarters building is overloaded with symbolic meaning and colourful geometries: it resembles nothing ever built before and incorporates influences from Pop Art and post-modern humour, including the tongue-in-cheek metaphor of the main entry gate, in the form of Mickey Mouse’s ears. A spectacular competition-winning design for Tokyo’s New City Hall (1985) was never built (although ideas from this project kept re-emerging in later proposals, such as at the large and airy indoor/outdoor atrium sliced by bridges, just as used ten years later for the Potsdamer Platz buildings in Berlin); the proposal was the only non-skyscraper project in the competition and this gigantic ‘groundscraper’ typology would occupy Isozaki for his entire career. When one turns a skyscraper on its side, creating a ‘groundscraper’, all of its intimidating ‘bullying power’ dissipates into a humbler serenity.

Isozaki commented that this phase of the Cold War era had come to an end and created an entirely new global situation, which followed on from the fall of the Berlin Wall and the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble.

Typical works from this phase include:

Tsukuba Center Building (1979–1983), Tsukuba, Japan.

Museum of Contemporary Art MOCA (1981–1986), Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Palau Sant Jordi Stadium (1983–1990), Barcelona, Spain; Sports Hall for the 1992 Summer Olympics; followed by the Palafolls Sports Complex Pavilion (1987–1996), Barcelona, Spain.

New Tokyo City Hall (1985–1986, unbuilt), Tokyo, Japan.

Kamioka Town Hall (1975–1978), Kamioka, Japan.

Team Disney Orlando (1987–1991), FL, USA.

Bond University, Library and Administration Building (1987–1989), Gold Coast, Australia.

Kitakyushu International Conference Center (1987–1990), Fukuoka, Japan.

4.3. Phase III: 1990–2000: Architecture as a Sculptural Statement and Experiment

The third phase of his career can best be described as a paradigm shift towards the thought ‘anything seems possible’; further heralding his career with high-profile projects and clients and firmly establishing Isozaki as the most influential figure in Japanese architecture in this decade. The conceptually powerful and often provocative designs of this phase looked more Japanese when compared to the previous, internationalised phase; for instance, the buildings in Mito and Krakow, which showed a typical Japanese aesthetic. Edan Corkill noted: “If the entire Japanese architectural fraternity was one big royal family, then Arata Isozaki would be a king approaching the end of a long and glorious reign.” (

Corkill 2008, p. 4). Indeed, during this phase his influence gradually spread further afield, mirroring the growth of his stature.

Isozaki developed a more hyper-modernistic style in this phase, with buildings such as the Art Tower of Mito and Domus, La Casa del Hombre, in Galicia, Spain. Much of his work in Spain was generated by the highly successful Olympic stadium Palau Sant Jordi on Barcelona’s Mountjuic that he created for the 1992 Olympics; it was also a response to the beginning of Japan’s economic recession in 1991, which forced most architects to look beyond Japan. The buildings designed and built during this phase are a string of elegant public works with a cultural function, ranging from large concert halls, museums, art galleries, universities and libraries to cultural centres (contracts mostly won through design competitions). Isozaki therefore developed vast expertise in museum technology and acoustics for concert halls. During this period, he developed the concept of the

Third Generation Art Museum (1991), which he described as a “site-specific and art-specific museum” (

Lehmann and Feireiss 1994). The design of Art Tower Mito is influenced by Brancusi’s

Infinite Column and the idea of an infinitely extendable tower; it creates a powerful civic symbol for an otherwise nondescript new town (see

Figure 1). Despite the large-scale works, he always maintained an interest in small projects, such as the Nagi Museum, furniture design and temporary exhibitions, in line with the enormous respect Japanese culture has for small things and its dedication to refinement: just think of the ritual of the traditional Japanese tea ceremony and its refinement (

GA Architect 2000). Designs in this phase include fiercely elegant buildings such as the elegant Kyoto Concert Hall, Nara Centennial Hall and Atea Twin Towers (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Around 1993, he started to incorporate organic curved elements and surfaces in his designs; the use of curves started to appear more and more frequently in designs (for instance, in his projects in China, Qatar and for the Florence railway station proposal).

Isozaki would claim that the phase of contextual local architecture had come to an end with the complete globalisation of architecture.

Typical works from this phase include:

Art Tower Mito (1986–1990), Ibaragi, Japan.

Centre of Japanese Art and Technology (1990–1994), Kraków, Poland.

Donau City Twin Towers (1991–1992, 1st Prize, unbuilt), Vienna, Austria.

Kyoto Concert Hall (1991–1995), Kyoto, Japan.

Nara Centennial Hall (1992–1998), Nara, Japan.

Mino Ceramic Park and Museum (1996–2002), Gifu, Japan.

Domus—La Casa Del Hombre (1991–1995), Coruña, Spain.

Buildings C2/C3 at Potsdamer Platz (1993–1999), Berlin, Germany (Arata Isozaki and Steffen Lehmann).

Nagi Museum of Contemporary Art (1991–1994), Nagi, Okayama, Japan.

Shizuoka Convention and Arts Center GRANSHIP (1998), Shizuoka, Japan.

The Bass Museum of Art, Miami (2000–2001), FL, USA.

COSI Columbus Science Museum (1994–1999), OH, USA.

New entrance of the Caixa Forum Barcelona Building (1999–2002), Barcelona, Spain.

4.4. Phase IV: 2000 to Present: The 21st-Century: Digital Architecture as a Form of Global Endeavour

In his most recent phase, Isozaki has continued to push the envelope of what is possible urbanistically, socially and technologically, creating new forms that have often challenged gravity. In an age where the difference between ‘urban’ and ‘non-urban’ is increasingly blurred, a new concept of the poly-centric city has emerged. The projects completed in this phase can mostly be found in the fast-growing mega-cities of Asia rather than in Japan; a sign that architecture has become a truly globalised endeavour, catering for a global consumer society. Globalisation also leads to an architecture that is less distinctive to any one city or country, because it is abstract rather than locally anchored by regional materials and typologies. Many of these projects, clusters of high-rise towers as variations of his early themes, are now in China, Vietnam and Central Asia, in the Middle East and in Qatar. The National Library in Qatar is a high-rise tower that calls his unbuilt project of the ‘City in the Sky’ 45 years earlier to mind; it took a lifetime to finally get the idea built (see

Figure 4). In 2005, Isozaki founded an Italian branch of his office; in Milan, where the CityLife office tower in the former trade fair area in Milan and other works have been realised. Isozaki’s contribution to the CityLife project is known as

Torre Isozaki, a dramatic 207-meter-high office tower that, instead of the classic image of a three-part tower (with base, shaft and crown), builds on the concept of the ‘endless tower’, referring again to Brancusi’s endless column. His projects in this phase highlight the contradictions and discontinuities of the contemporary city, where organised and orderly planning is now rarely possible, and sometimes evoke an informational city as an advanced network of ICT systems (such as his projects in China). Not unlike Le Corbusier, Isozaki’s late work has changed to become more organic, often with curvilinear forms derived from nature forming cave-like spaces and bone-like structures; for instance, the Himalayas Art Centre and the Qatar Convention Centre are good examples of the organic late works with which Isozaki has searched for deeper meaning outside of ordinary criteria. At the beginning of the new millennium and in a tech-saturated age of networks, his recent works appear like ‘Google Earth architecture’ for the age of satellite surveillance, in an age that has radically altered the way we perceive the urban environment. This applies especially to rapidly growing cities in China, where there is increasing uncertainty about the physical presence of architecture in the world; these works make that uncertainty explicit. The impact of globalisation on architecture and cities has yet to be seriously studied and investigated. This fourth phase of his work is still ongoing.

Typical works from this phase include:

Shenzhen Cultural Center and Library (1998–2007), Shenzhen, China.

Torino Palasport Olimpico Stadium (2002–2006), Turin, Italy.

Isozaki Atea residential twin towers (1999–2009), Bilbao, Spain.

Qatar National Library (2002–2007), Doha, Qatar.

Museum of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing (2003–2008), Beijing, China.

New Concert Hall Building (2003–2010), Thessaloniki, Greece.

Zendai Himalayas Art Center (2003–2010), Shanghai, China.

Diamond Island and Metropolis Thao Dien (high-rise building cluster; 2006–2012), Ho-Chi-Minh City, Vietnam.

Coliseum da Coruña (1990–1991), A Coruña, Spain.

Qatar National Convention Centre and Ceremonial Court, Education City (2004–2010), Doha, Qatar.

CityLife ‘Allianz Tower’ office high-rise (2003–2012), Milan, Italy.

The University of Central Asia’s three campuses in: Tekeli, Kazakhstan; Naryn, the Kyrgyz Republic; and Khorog, Tajikistan (2014–present).

5. Legacy: A Forgotten Visionary Ready for Rediscovery?

Arata Isozaki’s architectural position as artist-architect has often been controversial and polemical but is still highly relevant today. His activities are not limited to architecture but include writing, criticism, the judging of architecture competitions and collaborations with artists. Overlooked for the Pritzker Prize (which was the only time I have seen him be bitter about the fact that he was a member of award juries numerous times (including for the Pritzker), promoting avant-garde architects and helping younger architects to start their career and make their ideas a reality, from Holl, to Hadid, to Sejima and Aoki, and numerous others, while never himself the recipient of the prestigious award), it has frequently been Isozaki who created the space and freedom for other Japanese architects to use their designs to propose radical critiques of society and innovative solutions to changing lifestyles.

Isozaki, once called “the Emperor of Japanese Architecture” by Tadao Ando (1985), has won multiple international awards such as the RIBA Gold Medal in 1986 and the Chicago Architecture Award in 1990, but the Pritzker Prize is arguably the most important of all architecture awards and Isozaki would be a deserving recipient. Perhaps his use of a variety of historical references in an unrestrained way (during his post-modern phase) is the aspect of his work that is most misunderstood and complex, triggering scepticism by a younger generation? The Pritzker Prize jury is often looking for consistency, favouring architects who have done one thing and have not constantly changed and who therefore can be easily ‘labelled’ (for more information, see:

www.pritzkerprize.com). The heterogeneous and constantly transforming oeuvre of Isozaki with its diversity and complexity would require some serious effort to grasp and its open-ended questions (rather than delivering simplistic, singular answers) do not sit easily with such juries.

After spending a couple of years in the Tokyo office and becoming Isozaki’s trusted aide, I was fortunate to enter into a project partnership with him in 1993 for the two large buildings at Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz. In 1995, when Isozaki lost interest in this distant project with a complicated client, the building’s design and realisation were entirely taken over by my own practice. Thanks to the generosity of Arata Isozaki, I was able to team up with him as a 30-year-old architect and have my name associated with this prestigious project.

Today, architects are subjected to elaborate forms of control and project management, squeezing out all complex invention and elements of complicated geometry in the name of reducing the risks of the project. Isozaki has showed us how powerful buildings can be. The ideas and formal originality that continue to drive his architecture are still influential internationally. There is no doubt that he is one of the most important and influential architects of the second half of the 20th century. His work, although not yet entirely and fully understood, is still very relevant (

Oshima 2009). I predict that Isozaki’s oeuvre and legacy is such a rich resource that it will soon again become the subject of intensive study, rediscovery and reappraisal and will be appreciated once again by future generations.

The four phases of Isozaki’s work outlined in this article allow us to better understand his conceptual themes and appreciate his unique talent and influential position. His concepts and theories over the last six decades have been immensely influential and are still highly relevant to architectural design practice today. Within 20th century architecture, Isozaki’s work is unusual and highly original and deserves more recognition. The author believes it is now timely to revisit the work and reappraise it in its full impact (including the potentiality of collaborative efforts). One could argue that Isozaki has created an architecture so personal in its ideas and concept of space that it defies characterisation as belonging to any single school of thought (see

Figure 5). His great personality, sense of humour and fascinating complex character, combined with his modesty and extraordinary generosity has that helped so many younger architects to launch their careers, will not be forgotten. A true visionary and master architect, Isozaki turns 86 years old on 23 July 2017.