The Oval Engravings of Nabara 2 (Ennedi, Chad)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Nabara 2 Shelter

3. Recent Engravings and Pastoral Paintings

4. The Oval Petroglyphs

- E1 and E2: two oval engravings subdivided into squares by a longitudinal element and four transversal elements resembling a framework (Figure 15). Patterns of differently angled lines fill the square subdivisions within the reticulate motif.

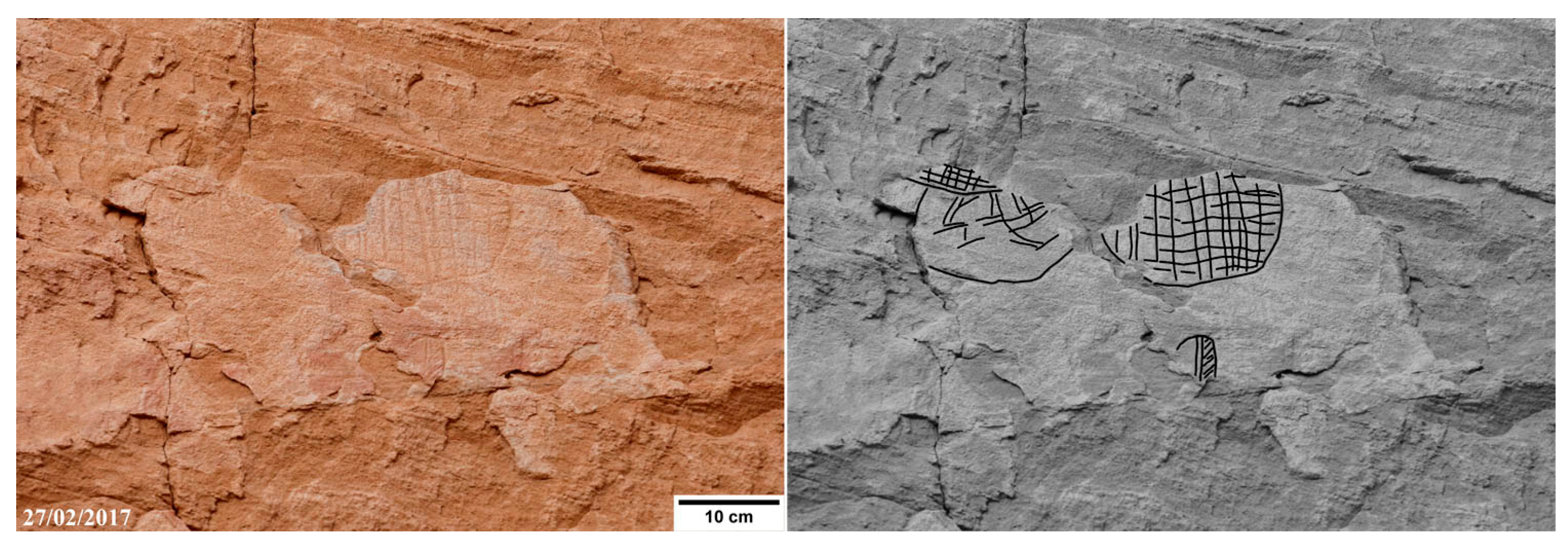

- E3: a cluster of partially preserved oval engravings (Figure 16). A vertical element drawn by two parallel lines halves in two the largest one, apparently surviving for the lower third of its original area only. A pattern of oblique lines, up left-to-right, fills the left part. A thin horizontal stripe joins the vertical element on the lower right part; patterns of oblique and vertical lines decorate the spaces above and below. A longitudinal vertical element subdivides the small oval engraving to the right; an irregular grid pattern fills the right part. A pattern of lines, up left-to-right, decorates the left part; two slightly curved vertical lines intersect this pattern. A pattern of horizontal lines decorates the upper right quarter of the lowest engraving of the cluster, while the left upper quarter is apparently void. Short segments of the outlines of two more oval engravings are recognizable near the upper and lower border of the eroded surface hosting the E3 cluster.

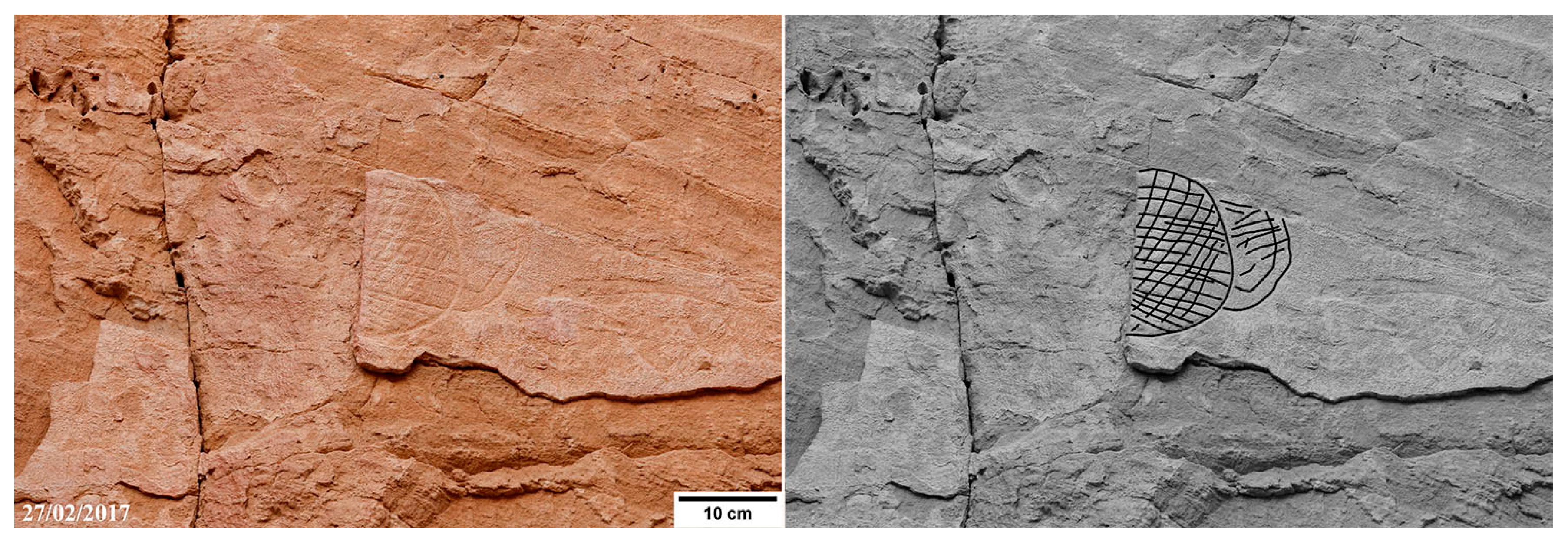

- E4: two paired oval engravings. A vertical longitudinal element subdivides the one to the right into two sectors, internally decorated with horizontal lines (Figure 17). A reticular graphic element subdivides into squares the oval engraving to the left. Patterns of oblique lines, up left-to-right and up right-to-left, symmetrically fill the resulting square subdivisions.

- E5: a fragment of an oval engraving featured by a longitudinal element with a tapering end jutting out from the round edge (Figure 18). A pattern of lines, up left-to-right, fills the surviving left upper quarter of what could have been the original motif. A pattern in mirror symmetry, up right-to-left, decorated the right part, as can be deduced by the narrow strip of engraved rock still preserved to the right of the longitudinal element.

- E6: an oval motif survived the destructive flaking process only by its central part (Figure 19). Deeply engraved horizontal lines define strips of different height, each one filled with angled grids. To its lower left and right, tiny relics of four more engravings are visible. The three to the right preserve traces of internal decorations.

- E7: a cluster of four oval engravings. The central one is a simple wide rounded shape with an internal pattern made of an irregular rectangular grid (Figure 20). The one to the left, similar in size but almost completely deleted by erosion, is decorated with a disorderly pattern of crossing lines. A possible third engraving, decorated with a pattern of angled grid and preserved as a very small fragment, is apparently overlapping the top of the left engraving. Few centimetres below the central engraving, a much smaller oval engraving is visible. A vertical element traced by two lines subdivides this oval into two parts; a pattern of oblique lines, up left-to-right, fills the right part.

- E8: two partially overlapping oval shapes (Figure 21). A pattern made of angled lines features the engraving in the foreground. A double rim and a rectangular grid with horizontal lines more deeply incised characterize the engraving in the background.

- E9: an oval engraving featured by patterns of angled lines, without a clearly organized internal order (Figure 22).

5. The Nabara 2 Oval Engravings in Their Regional Context

6. Future Research Avenues

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AARS. 2009. Rules of Behaviour on the Rock Art Sites. Association des Amis de l’Art Rupestre Saharien. Available online: https://aars.fr/deontologie_en.html (accessed on 3 September 2017).

- Bailloud, Gerard. 1997. Art Rupestre en Ennedi. Saint-Maur-des-Fossés: Éditions Sépia. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarik, Robert G. 1994. A Taphonomy of Palaeoart. Antiquity 258: 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Johannot, Purissima, Alain-Michel Boyer, and Jean Paul Barbier. 2010. Shields: Africa, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. From the Collections of the Barbier-Mueller Museum. New York: Prestel Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Choppy, Jacques, Brigitte Choppy, Sergio Scarpa Falce, and Adriana Scarpa Falce. 1996. Images Rupestres de l’Ennedi, Tchad: Zone Nord—Niola Doa. 1° Partie. Fleurier: J. Choppy. [Google Scholar]

- Choppy, Jacques, Brigitte Choppy, Sergio Scarpa Falce, and Adriana Scarpa Falce. 2003. Images Rupestres de l’Ennedi, Tchad: Le Centre et le Sud-est. 3° Partie. Fleurier: J. Choppy. [Google Scholar]

- Cignoni, Paolo, Marco Callieri, Massimliano O. Corsini, Matteo Dellepiane, Fabio Ganovelli, and Guido Ranzuglia. 2008. MeshLab: An Open-Source Mesh Processing Tool. Paper presented at Sixth Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference, Salerno, Italy, 2–4 July; pp. 129–36. [Google Scholar]

- Civrac, Marie-Anne. 2014. Le Site a Peintures Rupestres de Dibirké au Sud-ouest de l’Ennedi (Tchad). Les cahiers de l’AARS 17: 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Di Lernia, Savino. 2017. The archaeology of rock art in Northern Africa. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Edited by David Bruno and Ian J. McNiven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, Jon. 2017. DStretch (plugin to ImageJ). Available online: http://www.dstretch.com/ (accessed on 3 September 2017).

- Holder, M. K. 2001. Why Are More People Right-Handed? Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-are-more-people-right/ (accessed on 3 September 2017).

- Institut Géographique National. 1961. Archeï. République du Tchad—Feuille NE-34-IV. Fond Topographique au 1/200,000. [Google Scholar]

- Kröpelin, Stefan. 2016. Secret Sahara Reveals Fairy-Tale Formations and Ancient Lakes. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2077342-secret-sahara-reveals-fairytale-formations-and-ancient-lakes/ (accessed on 3 September 2017).

- Kröpelin S., Dirk Verschuren, Anne Marie Lézine, Hilde Eggermont, Christine Cocquyt, Pierre. Francus, Jean-Pierre Cazet, Daniel Joseph Conley, Matieu Schuster, and Daniel R. Engstrom. 2008. Climate-Driven Ecosystem Succession in the Sahara: The Past 6000 Years. Science 320: 765–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Quellec, Jean-Loic, Jon Harman, Frédérique Duquesnoy, and Claudia Defrasne. 2013. DStretch® et l’Amélioration des Images Numériques: Applications à l’Archéologie des Images Rupestres. Les Cahiers de l’AARS 16: 177–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lenssen-Erz, Tilman. 2012. Pastoralist Appropriation of Landscape by Means of Rock Art in Ennedi Highlands, Chad. Afrique. Archéologie et Arts 8: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen-Erz, Tilman. 2015. Cooperation or Conflict? Identity and Scarce Resources of Prehistoric Saharan Pastoralist. African Study Monographs 36: 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- MEH. 2015. Carte hydrogéologique de la République du Tchad au 1:200,000, Ouvrages et Ressources, feuille NE-34-04 Archeï. Ministre de l’Elevage et de l’Hydraulique. Produit réalisé par UNITAR et Swisstopo, Genève et Berne. Available online: https://reseau-tchad.org/upload/Documents/Cartes/NE34-04_Archei_2015_MEH_web.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2017).

- Menardi Noguera, Alessandro, and Andrea Bonomo. 2014. The Chéïré-1 Painted Shelter (Ennedi, Chad). Paper presented at AARS meeting, Bergamo, Italy, May 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petch, Alison, and Sandra Dudley. 1997. Shields and Objects, Anthropology and Museums. Available online: http://era.anthropology.ac.uk/Era_Resources/Era/Pitt_Rivers/misc/introset.html (accessed on 3 September 2017).

- Pitt Rivers Museum. 2017. Pitt Rivers Museum Database of Photograph Collections. Available online: https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/databases (accessed on 3 September 2017).

- Simonis, Roberta. 1996. Azrenga. In Arte Rupestre nel Ciad. Borku—Ennedi—Tibesti. Edited by Negro Giancarlo, Adriana Ravenna and Roberta Simonis. Segrate: Pyramids, pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2017. Ennedi Massif: Natural and Cultural Landscape. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1475/documents/html (accessed on 24 September 2017).

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menardi Noguera, A. The Oval Engravings of Nabara 2 (Ennedi, Chad). Arts 2017, 6, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts6040016

Menardi Noguera A. The Oval Engravings of Nabara 2 (Ennedi, Chad). Arts. 2017; 6(4):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts6040016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenardi Noguera, Alessandro. 2017. "The Oval Engravings of Nabara 2 (Ennedi, Chad)" Arts 6, no. 4: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts6040016