2. Bormla’s Socio-Demographic Characteristics

This paper is based on the premise that crime and victimisation are rooted in the social and physical characteristics of communities [

2], an approach adopted by environmental criminology. This approach was adopted in this paper as a means to find out which situational factors are linked with the particular pattern of crime found in Bormla. This section will begin by presenting some of the socio-demographic characteristics of the context under scrutiny. The interest in Bormla arises from the fact that this town is often associated by the Maltese general public with crime since a substantial number of convicted persons come from this area, as will be delineated below.

Bormla exhibits high population density, high dwelling density and the highest offender rate in the Maltese Islands [

3]. Prior to World War II, it was Malta’s industrial hub, as the British naval shipyards were located in the area. Bormla started experiencing high population turnover and a shrinkage in its population during and after World War II. Bormla suffered intensive bombing during this war because the shipyards were the main target of aerial bombing. This town is physically segregated from the rest of Malta by a system of bastions built during the reign of the Order of St. John which ruled over Malta from the 16th to the 18th century.

The resultant destruction caused by the war forced a number of residents of this area to seek shelter in safer areas in the Maltese Islands. Those who moved out of the area tended to be families with the material means to find alternative shelter elsewhere. A good portion of these wartime refugees did not return after the war [

4]. The war led to a structural change in the demographic and social composition of the area. Boswell maintains that the “post-war repopulation of the Cottonera is said to have introduced a poorer and socially more depressed working-class population than it had before its elite moved out” [

4].

The post-war era saw massive reconstruction programmes taking place in the area. A number of social housing projects in Bormla were built by the British in areas that had suffered war damage. Other social housing projects were built after independence (Malta became independent in 1964). The majority of social housing units in the Maltese Islands are concentrated in Valletta and Bormla, according to statistics derived from the Maltese Lands Department. In fact, 8.8% of the social housing units in the Maltese Islands are to be found there, according to the Maltese Department of Lands [

5] (the Maltese social housing agency). Unfortunately, the architecture of these social housing projects clash with the medieval and baroque architecture prevalent in the area.

The propensity for destroying old houses and replacing them with blocks of flats to accommodate families with social problems means that Bormla was, in 2011, still an area with a high population density at 5,784 persons per km

2 as compared to 7,125 in 1995 [

6]. It is also an area which suffers from a lack of open spaces. There are also a number of dilapidated and abandoned buildings which residents avoid since drug-related activities tend to take place in such areas and serve as “no-go” areas for the locals. Some of the mediaeval and baroque historic buildings found here are inhabited by squatters who have no inclination (nor sometimes the means) to renovate both the place and its surroundings [

7].

Old houses within the core of the city are rented out at cheap rates and it is not unusual for a house to be sub-divided into separate units and rented to different households. Since the rent for this sub-standard housing tends to be low, materially deprived groups tend to be attracted to the area [

8]. Long-term residents regard the people who move into Bormla as “outsiders” [

9] and a “scourge” since, according to them, their behaviour gives the place a bad name. The “locals” blame policy makers for building flats in an area which was already overpopulated and then “dumping” problem families there. Locals and service providers blamed some local councillors from neighbouring towns for this state of affairs. They also cited a list of families from these neighbouring towns which had been given alternative social housing in Bormla in order to “clean up” their own town. When this issue was raised in an interview with one of the councillors in question, this person stated that these families were persuaded to leave the area, but did not go into detail on the type of persuasion used.

“Outsiders” provided with social housing in Bormla might not feel comfortable living there. Some mentioned the fact that they were now cut off from the social networks they had made in their town or village of origin, social networks which are essential for survival for people living at or below the official poverty line. Newcomers also find it difficult to integrate into this close-knit community, where most people are related to each other, and practically everybody knows each other’s family history and circumstances.

To make matters worse, people living in the area have been badly hit by the economic restructuring which took place in the Maltese Islands in the first decade of the 21st century. A good portion of Bormla residents used to work in the dockyards and shipbuilding industries [

10]. Their numbers decreased drastically when these were privatised in 2010. Another segment of the population worked within the manufacturing industry. The re-location and down-sizing of a number of factories in the first decade of the millennium [

7,

11], left a number of people from the area without employment, or precariously employed.

The unemployment rate in the Southern Harbour area in the first decade of the millennium was comparatively high [

12]. It therefore came as no surprise when the Southern Harbour district (Bormla is one of the localities found in this district) ranked second worst in the 2007 Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) [

13] and in subsequent ones. In the SILC survey, 17% of the residents living in the Southern Harbour district were found to be living at or below the poverty line. In this survey, the Gozo and Comino district was found to have the highest percentage of people living at or below the poverty line (18% according to NSO [

14]). The Gozo and Comino district, however, did not have as high a crime rate as Bormla.

Ameen [

15] states that the number of people dependent on state handouts is higher in Bormla than in other areas of Malta. This high rate of dependence on social welfare is due to the high rate of unemployment found in the area, as noted above. The high unemployment rate is also linked with the comparatively higher illiteracy rate. Data elicited from the 2005 census demonstrates that the percentage of illiterate Bormla people was 14.9%, more than double the national average (7.2% of the population, according to Galea [

16]). Although attempts have been made to ensure a better academic future for the young people of this locality [

17], educational attainment among the young of Bormla might not be reversed in the future since this is a locality which suffers from a high rate of school absenteeism when compared to other areas of Malta [

18].

Formosa [

19] also notes that Bormla hosted the highest offender rates between 1980 and 1999. Before this period, Valletta was the city with the highest rate of offenders (

Table 1). This concentration of registered offenders in Bormla might have been caused by social housing placements as well as the availability of cheap accommodation which might have attracted those without enough material means to find rented accommodation in the area.

Table 1.

Offender Residence Changes: 1950–1999.

Table 1.

Offender Residence Changes: 1950–1999.

| Locality | Offender %

1950 to 1959 | Offender %

1960 to 1969 | Offender %

1970 to 1979 | Offender %

1980 to 1989 | Offender %

1990 to 1999 |

|---|

| Bormla | 6.3 | 5.4 | 9.3 | 11.1 | 14.2 |

| Valletta | 10 | 11.8 | 17.4 | 9 | 12.7 |

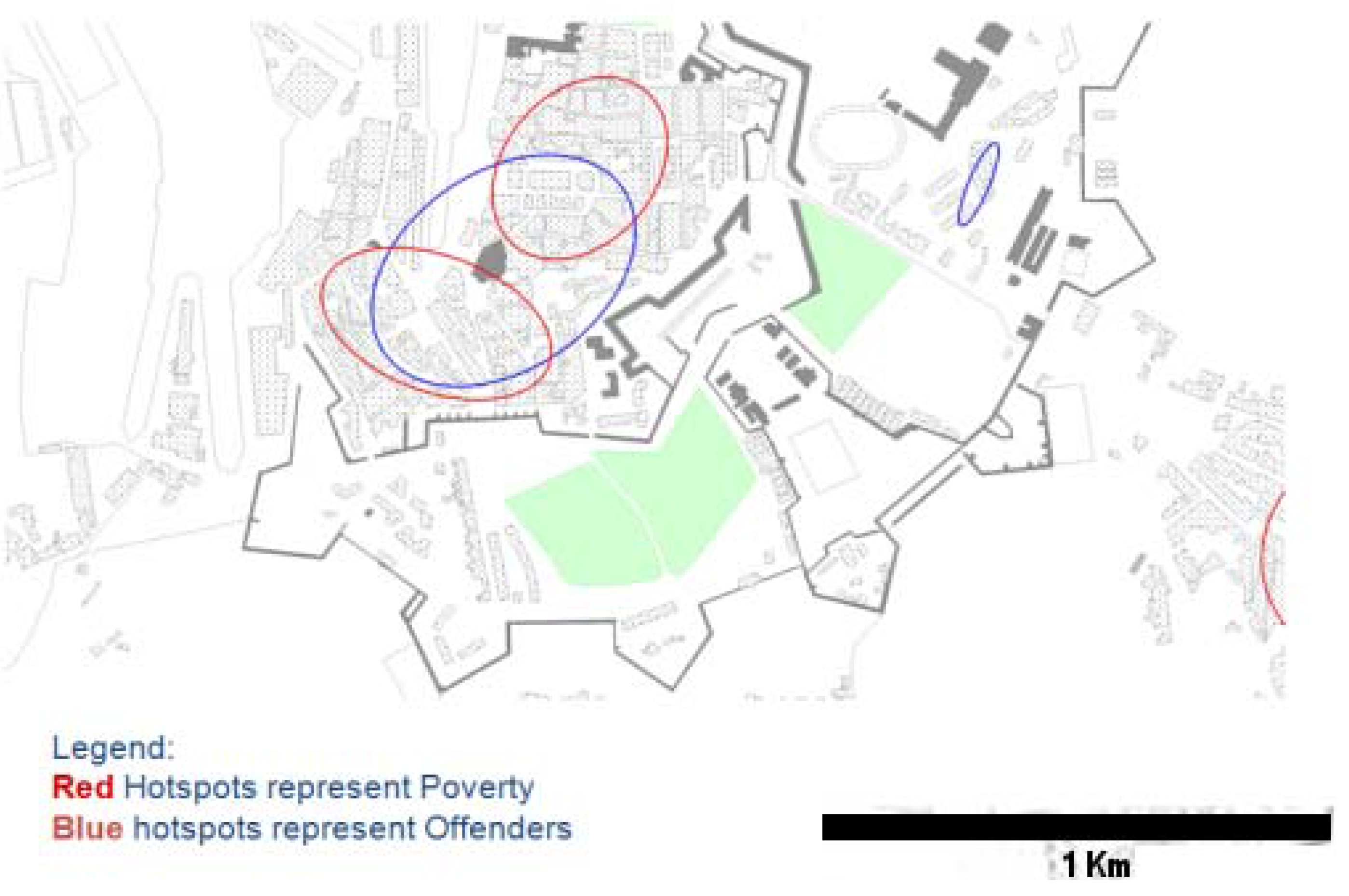

Figure 1 shows that the majority of offenders living in Bormla tended to live in poverty hotspots, namely, those poverty hotspots which registered 3.5 times the national rate [

3]. Ex-offenders are more likely to face poverty because, as Camilleri [

20] points out, they are less likely to find work once they come out of prison. The spatial correlation resultant from the analysis of the two datasets highlights the fact that the areas where poverty is concentrated also host the offender residences. In addition, when offenders leave prison, those who do not return to their source town migrate to poor areas in other towns, mainly Valletta.

This concentration of ex-offenders in the area may be high also because it has been attested that materially deprived people are more likely to be arrested, to be charged by the police, to be denied bail, to appear in court without adequate legal representation, and therefore more likely to be convicted [

4]. One should, however, note that material deprivation as such does not push people into committing crime or other forms of antisocial behaviour.

Sampson, Raudenbush and Felton [

21] maintain that higher crime rates in socially deprived areas might derive from a lack of collective efficacy. Constant population turnover, especially in certain social housing estates, can lead to a lack of collective efficacy. This lack of collective efficacy is, however, prevalent in certain social housing estates and not in others. The data analysed in this paper demonstrates that, in Bormla, crime is linked with poverty, lack of collective efficacy, and of windows of opportunity.

Figure 1.

Crime Maps—Overlaying Offender and Poverty Hotspots.

Figure 1.

Crime Maps—Overlaying Offender and Poverty Hotspots.

3. Official Crime Rate

In this section, data provided by the CMRU (Communications and Media Relations Unit) of the Malta Police Force will be analysed to find out what the official crime rate in Bormla was in 2009 when compared to the rest of Malta, and what types of crime occurred there. The statistics provided by the CMRU depend on reports made to the police. One should point out that not all reports are registered when antisocial behaviour comes to police attention.

When one compares Bormla’s crime rate with that registered for the rest of Malta, one finds that the crime rate, as registered by the CMRU in 2009, was higher than the average national figure for crime, as

Table 2 attests. One, however, should point out that the first four primary crime hotspots in the Maltese Islands in 2009 were Paceville (St. Julian’s), followed by St. Paul’s Bay, Sliema, Valletta and then Bormla [

19].

Table 2.

Official crime rate in the Maltese Islands and Bormla in 2009.

Table 2.

Official crime rate in the Maltese Islands and Bormla in 2009.

| National Population | 395,000 |

| Crimes | 11,953 |

| Crimes per 1000 persons | 30.26 |

| Bormla Population | 5,600 |

| Crimes | 187 |

| Crimes per 1000 persons | 33.39 |

The main types of crime recorded in Bormla between 2004 and 2009 were mainly theft, followed by damage, bodily harm and attempted offences. When the crimes committed were collapsed, it was evident that crime against the person was higher than the national average, while crime against property was lower (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Type of crime committed in Bormla in 2009 compared to national figures.

Table 3.

Type of crime committed in Bormla in 2009 compared to national figures.

| Type of Crime | Bormla | National figures |

|---|

| Crime vs. property | 64.7% | 76.5% |

| Crime vs. person | 26.2% | 17.7% |

| Crime vs. general public | 0% | 0.8% |

| Attempted offences | 1% | 5.0% |

3.1. Areas in Bormla Where These crimes Are Committed

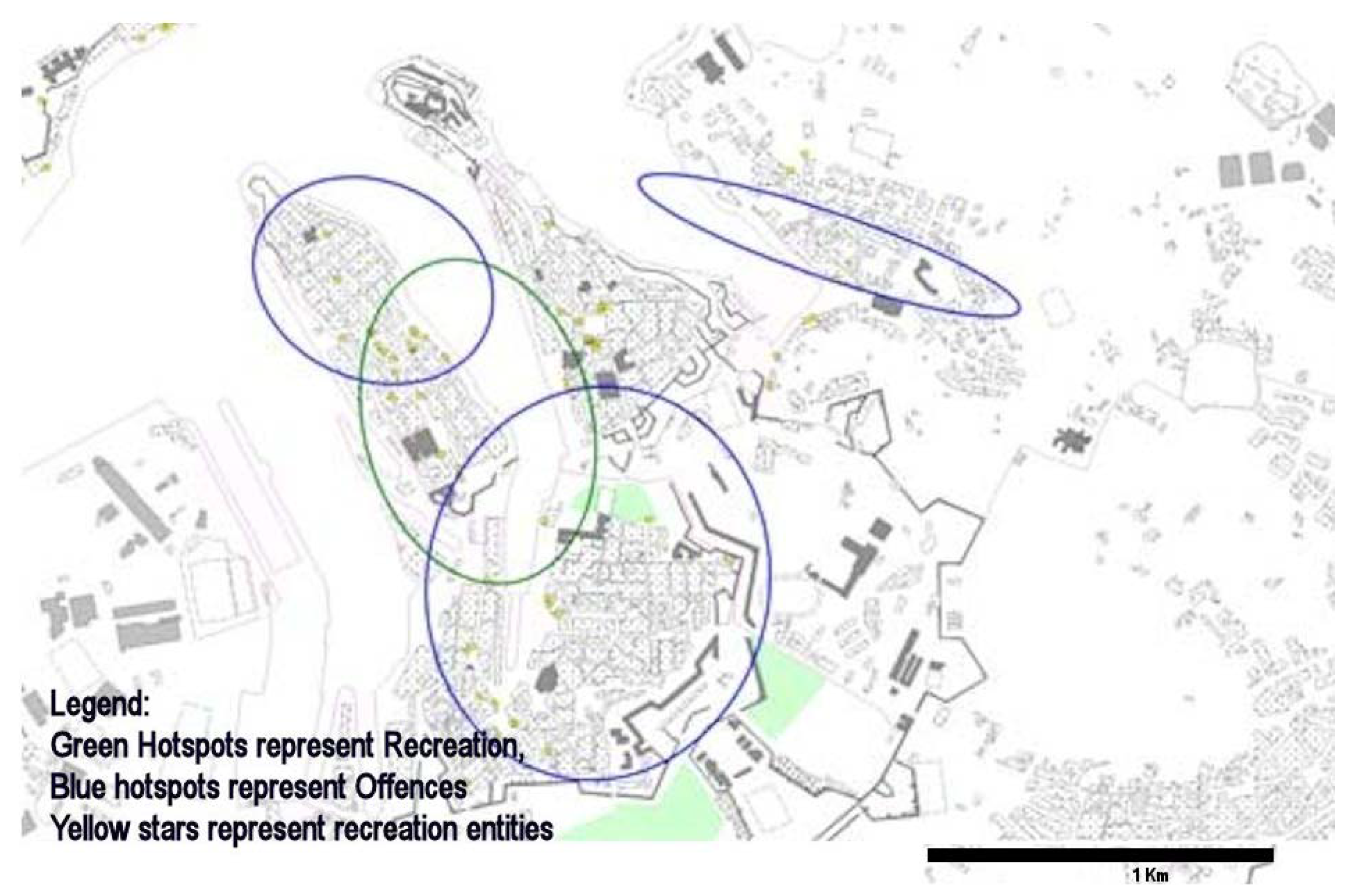

As

Figure 2 demonstrates, the registered crime rate in Bormla was highest in the areas where the poverty rate was high [

22,

23]. In terms of offence analysis, central Bormla is a relatively high concentration area of crime, as depicted in

Figure 2. This analysis also shows that in comparison to other areas in the Maltese Islands, Bormla has a hotspot that covers the entire urban area [

3].

Figure 2.

Crime Maps—Overlaying offence and Retail/recreation Hotspots.

Figure 2.

Crime Maps—Overlaying offence and Retail/recreation Hotspots.

Formosa [

3] combined the NNH analysis with Moran’s I Spatial Autocorrelation for poverty rate and offender density. The results show that there is a clustering of both poverty and offenders, at a Moran’s I of 0.028094 for poverty which is higher than that for offenders at 0.009482. A spatial analysis using 1NNH hotspots at 1 standard deviation indicates that 95.2 percent (37) of the forty 1990s offender hotspots are located within or intersect with poverty areas [

3].

Offence hotspots in Bormla are spread across the urban area but concentrations exist, located in an arc around the church, with two distinct clusters: one around the southeastern bastions, and another closer to the Bormla primary school and the Verdala social housing estate (

Figure 3). The school is located in a non-residential area, and this might be the reason why crime here prevails. The Verdala social housing project is also located on the outskirts of Bormla, but one cannot say that the area is uninhabited. Verdala is a fort built by the British during the 19th century to protect them from a “native” insurrection. After the war, it was turned into a temporary social housing estate until more appropriate housing quarters could be provided. Unfortunately, this never took place. This area is somewhat cut off from the rest of Bormla since it is a fort. A small number of families have been living there for a number of years, but the majority do not stay long because this area is associated with antisocial behaviour. Although the Verdala housing estate has been recently renovated, the fort was not built to provide family accommodation.

Figure 3.

Crime Maps—Bormla Offence Areas: 1NNH.

Figure 3.

Crime Maps—Bormla Offence Areas: 1NNH.

It is evident to those who are familiar with the geographical and social layout of Bormla, that criminal activity in 2009 took place in areas where there was a high concentration of residents living in social housing units or in privately rented accommodation (for example, an area called Fuq San Pawl). This, therefore, leads one to conclude that a lower rate of collective efficacy exists in areas where residents might not have had the time or capacity to form social networks with other people living in the area since they are constantly changing abode.

A high prevalence of crime also took place in commercial areas (e.g., Bormla Wharf and Gavino Gulia Square) and in less frequented public spaces (examples include Santa Margerita Square and Three Cities Road). Crime rates were also high in areas where there was a prevalence of neglected and abandoned houses such as Alessandra Street and Matty Grima Street, areas where a number of drug-related crimes took place, according to respondents who participated in the needs assessment study. Crime rates were lower in residential areas where there was a prevalence of home owners, and/or residents who had been living there for generations.

3.2. The Community’s Perception of Crime

Statistics give one interpretation of crime. It is also imperative to look at the community’s perception of crime since their experience of antisocial behaviour might be different from that which emerges from statistical analysis. For the purposes of this study, data from the Bormla needs assessment study will be discussed here. This section will focus on what residents feel about living in one of the crime hotspots in Malta.

When a sample of Bormla residents were asked in the needs assessment survey what types of antisocial behaviour took place in the areas where they lived, the four prevalent criminal and antisocial behaviours mentioned were drug-related crimes, unsupervised youth, followed by theft from vehicles, and theft of vehicles (

Figure 4). Although three of these crimes feature in the official statistics, it was surprising to note that residents were quite concerned about the neglect of children and young people living in the area, which they felt was almost as prevalent as drug-related crime. Their concern emanated from the fact that unsupervised youth were more likely to resort to antisocial behaviour. In fact, the local authorities were at one time very concerned about the fact that some of these children and adolescents were being used by drug pushers to deliver drugs. The residents were also afraid that the prevalence of drugs in the area might mean that young people living there might have more opportunity to dabble with drugs. Substance abuse not only has a deleterious effect on the person who abuses, but can also lead to crime.

Figure 4.

Criminal and antisocial behaviour in neighbourhood.

Figure 4.

Criminal and antisocial behaviour in neighbourhood.

The residents’ perception of crime in this survey does not concur with the crime statistics provided by CMRU, which are found in

Table 3. It is quite clear that the authorities were more likely to record and act on reports that concerned crime against property than those that concerned crime against persons. This issue was raised by a police officer himself who, when asked what type of antisocial behaviour prevailed in the area, mentioned domestic violence in the same breath as drug-related crime. Although the officer in question said that the police were constantly called to deal with incidents involving domestic violence, few of these incidents were officially recorded. This low official record for domestic violence might emanate from the fact that where this type of crime is concerned, police personnel in Bormla try to reconcile the two parties and/or involve other agencies.

In another section of the needs assessment survey, respondents were asked whether they or a family member had been a victim of crime in the 12 months prior to the survey. Around 17% of the respondents said that they or a family member had been a victim of crime or antisocial behaviour. When one compares the victimization rate found in

Table 2 (33.39 crimes per 1,000 population) with this result, one realizes that the respondents’ victimization rate was significantly higher.

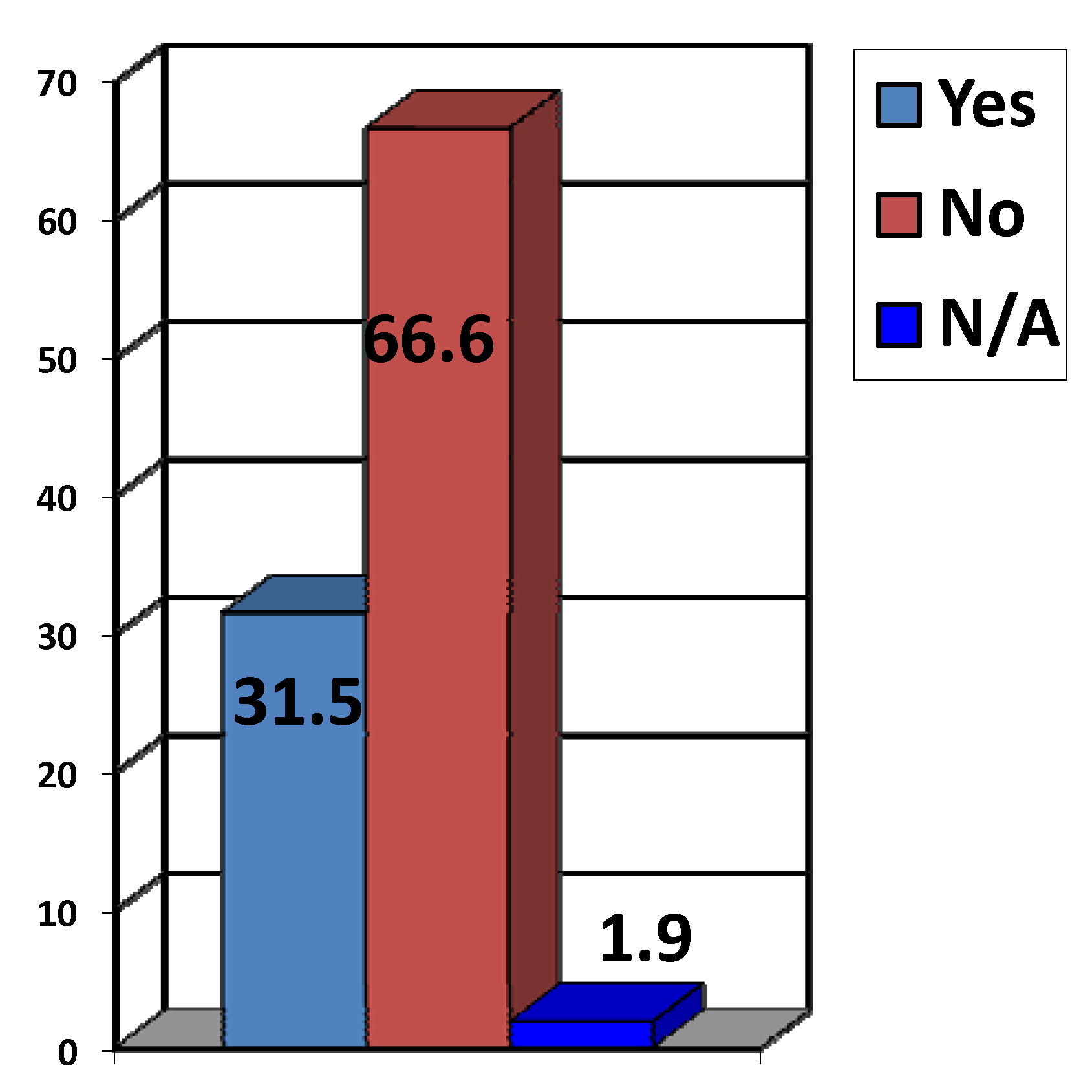

Respondents were also asked whether they had contacted the police in the 12 months before the survey was conducted, and 31.5% of respondents replied in the affirmative (

Figure 5). This result shows that this sample of residents contacted the authorities even when the crime or the antisocial behaviour did not concern them directly. One could therefore say that they were looking out for the interests of all those living in their neighbourhood. They were, in a way, acting as an informal neighbourhood watch.

Figure 5.

Did you contact the police in the last 12 months?

Figure 5.

Did you contact the police in the last 12 months?

A third of the respondents who said that they had contacted the police 12 months prior to the survey said that they were not satisfied with how the issue was dealt with. These respondents felt that the police had not done enough to settle the case, or did not show any interest in tackling the case when the incident was reported. These respondents felt that the authorities needed to do more to tackle the antisocial behaviours mentioned above. Some of the respondents answered that the police needed to make their presence felt in the area by conducting more foot and car patrols. As some of the respondents pointed out, the police only turned up when something went extremely wrong.

3.3. Perception of Safety

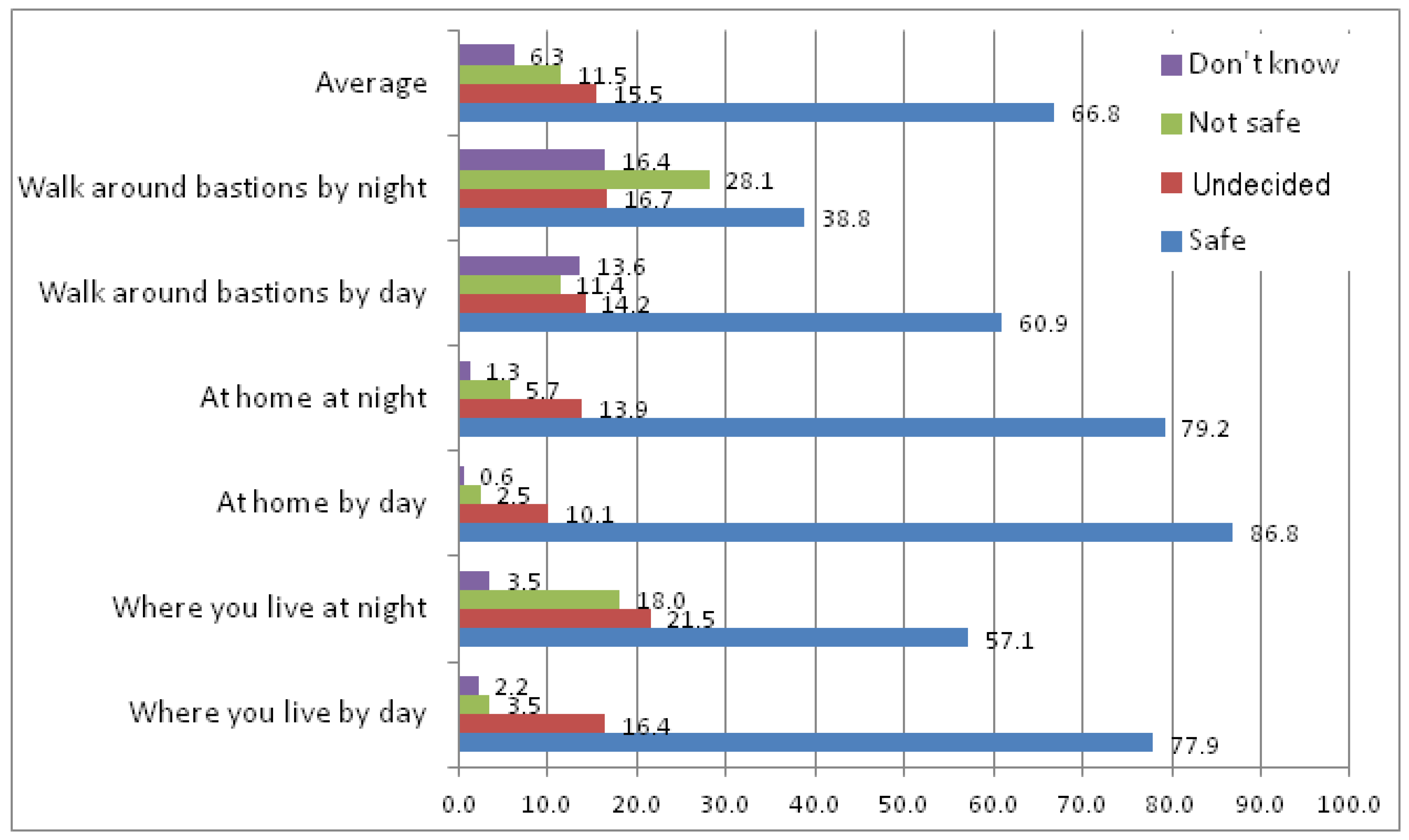

Although official statistics place Bormla as a crime hotspot, residents felt relatively safe living there. In fact, according to this survey, around 66.8% of respondents indicated that they felt safe living in Bormla (

Figure 6). They felt safe in their own home by day, although this sense of security dropped at night. They also felt safe in the area where they lived, although this feeling of safety differed by area, marital status, gender and age. As

Figure 6 demonstrates, respondents felt safer during the day. They felt safer in inhabited areas, and less safe in uninhabited ones. Female respondents were more likely to state that they felt safe in their neighbourhood and home by day than their male counterparts. They were, however, more likely to state that they did not feel safe at night.

Figure 6.

Perception of safety by time.

Figure 6.

Perception of safety by time.

The perception of safety also differed by area. Those living in the area of Santa Margerita (which includes the streets of St. George, St. Margaret, Narrow, and Windmill), as well as those living near St. Helen’s Gate (covering the area from the parish church up to St. Helen’s Gate) felt slightly less safe in their neighbourhood during the day than respondents living in other areas (

Figure 7). The areas mentioned here include tracts of non-residential space. Residents living in the St. Theresa area (incorporating Matty Grima, Nelson, St. Lazarus, Alexander, and St. Theresa Streets), Cottonera (including St. John t’Ghuxa, St. Nicholas, and Polverista) and the St. Helen area felt more insecure at night. Respondents living in the St. Helen area experienced a sense of insecurity both during the day and even more during the night. Those living in the St. Theresa residential area felt secure during the day, but then drug-related activities at night prompted residents to seek shelter inside their own homes. Although the Cottonera area was not linked by the police with criminal activities, residents stated otherwise. Some of the streets and lanes in the St. Theresa, St. Margaret, and Cottonera areas were considered as “no-go” areas by respondents for these reasons.

With regards to age, respondents aged been 37 to 60 were more likely to mention that they felt less safe in their neighbourhood and at home. This was especially true of residents who lived on their own. Older residents who felt safe were those who sought shelter with relatives or at a home for the elderly.

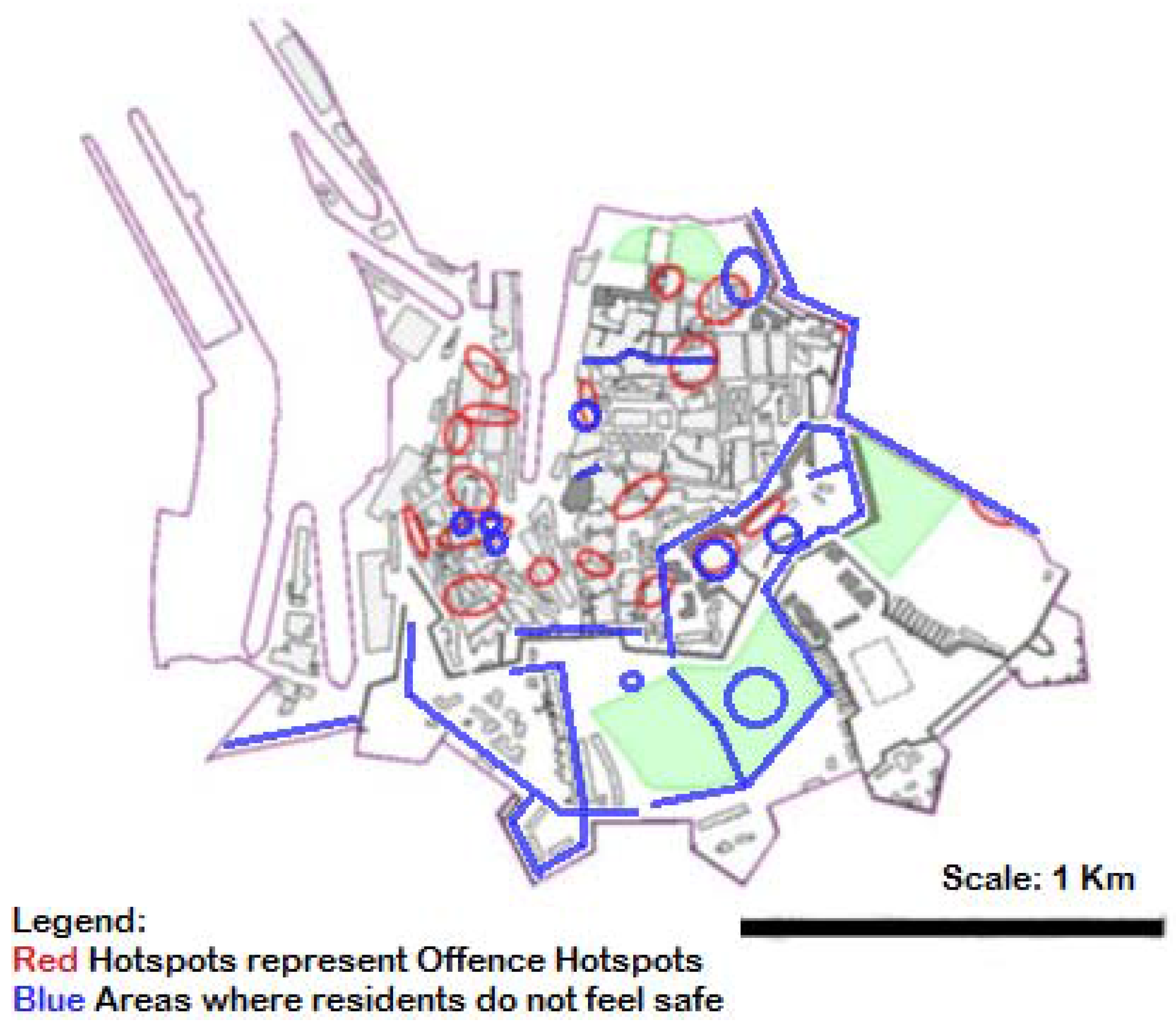

When respondents were asked to mention the areas in Bormla where they did not feel safe (the areas in question are marked in red in

Figure 7), they were more likely to mention the area within and surrounding the Verdala Housing Estate. The ring road around Bormla, starting from Polverista, passing by Cottonera Gardens up to the Convent of St. Theresa was also listed as an unsafe area. Few people live there. A number of bus stops are located on this route. Respondents who depended on public transport underlined the fact that they did not feel safe waiting on the bus stops located on this route, especially at night and in the early hours of the morning.

Figure 7.

Areas where residents do not feel safe.

Figure 7.

Areas where residents do not feel safe.

There were also some residential areas which were not considered safe. These were the areas where a number of bars are found, particularly the one near St. Helen’s Gate. Other bars are located close to the local police station. Some of the respondents living near these bars remarked that they did not feel safe when drug-related transactions took place in this area. A number of respondents also mentioned the fact that some of the patrons who frequented these places made a lot of noise, especially at night. Another group of respondents stated that some dilapidated and abandoned houses were often used by drug addicts to inject and/or “prepare” drugs.

Respondents also mentioned Fuq San Pawl, Matty Grima and Lazarus streets. The police were aware that drug-related transactions were taking place in these areas. They also mentioned some of the difficulties they met when it came to prosecute some of the drug dealers they arrested. Some mentioned that charges were dropped when “powerful” individuals intervened.

4. Discussion

4.1. Crime Rate and Crime Hotspots

When one compares the crime hotspots mentioned by residents with those which emerged from the GIS maps (

Figure 7), one notes some correlations. Some of the areas which featured in the GIS maps were mentioned. As one notes when comparing the crime hotspots (marked in red in

Figure 7) with the respondents’ feelings of lack of safety (marked in blue in

Figure 7), the feeling of lack of safety was not always linked with the level of criminal activity taking place in the area as registered by the police. This feeling of safety or lack of safety was also affected by the time of day, unilateral or multilateral use of space, age, gender and/or marital status of respondent. It was also related to the residents’ knowledge of what went on in the area.

Respondents felt that the crime rate in Bormla was higher than the rate recorded in official statistics. This issue was raised by residents in a meeting with the Police Commissioner which took place in April 2010. Residents felt that the police were not doing enough to stem the tide of illegal and antisocial behaviour prevalent in Bormla. A number of them complained that the police failed to act when they reported illegal or antisocial behaviour taking place in certain areas of Bormla.

One should also note that while respondents and the police felt that crime against the person (neglect of children coupled with domestic violence) and drug-related crime were high in Bormla, official statistics denote otherwise. Official crime statistics listed crime against property as being the most prevalent crime in Bormla, while respondents and the police mentioned crime against the person.

4.2. Who Commits Crime?

Bormla residents tend to attribute crime to the presence of “outsiders,” namely, people who have ended up living in Bormla either because they were sent there by the social housing authorities or because they could not afford to rent accommodation elsewhere. They believe that a stop to “social dumping” by the local authorities would help to minimise this crime rate. Statistics on the prevalence of ex-offenders living in the area cited by Formosa [

19] might give some credence to this perception. Formosa states, that prior to the 1980s, ex-offenders were concentrated in Valletta. These were relocated to Bormla during the period when the Valletta slum clearing project was enacted.

4.3. Where Does Crime Take Place?

As the data discussed above demonstrates, crime was more likely to occur in public spaces with single or low use by the community. These areas included commercial or leisure areas and other single-purpose uses of public space such as schools and circular roads. Within multi-purpose areas, crime rates were perceived to be higher in areas with a higher rate of abandoned houses, and near blocks in social housing estates. Areas with a preponderance of social housing and rented accommodation were more likely to have a high population turnover, and this might explain the lower community capacity in this area. As the data mentioned above demonstrates, there is a positive correlation between population, type of tenure, type of housing available and the crime rate.

4.4. Reasons for the High Crime Rate

Residents felt that the crime rate was high because the police rarely made their presence felt in the locality. The respondents lamented the fact that the police were rarely seen patrolling the area and that they only turned up when something went extremely wrong. They felt that they were inadequately protected by the police because as a community, as they reported, “We don’t count.”

Stiles

et al. [

24] correlate higher rates of violence, property crime and drug use with lower feelings of self-worth. Box [

25], however, maintains that victims who come from stigmatized groups find it harder to persuade others that they are victims. This seems to be the case here. Croall [

26] adds that the processes of victimization are socially, economically and culturally situated, as is true for Bormla. Low-status groups are more likely to be placed at the lower end of the victimisation hierarchy although they are more likely to be arrested, as statistics demonstrate. Data derived from the needs assessment study demonstrates that residents felt that they were less likely to be perceived as victims, and that their demands for protection were not being taken into consideration. This made them feel neglected by the authorities concerned. Shiell and Zhang [

27] attest that this feeling of powerlessness is prevalent in depressed, socially excluded areas.

Agnew [

28] adds that neighbourhoods with a concentration of socially disadvantaged people living in bad social conditions tend to have a concentration of angry and frustrated residents who might express this frustration by becoming physically violent. This statement might explain why the crime rate against the person in Bormla was higher than the national average. It might also explain why the crime rate in Bormla was higher when compared to other districts and/or areas having, statistically speaking, high concentrations of people living at or below the poverty line. Baron

et al. [

29] note that violence tends to prevail in urban settings where people are exposed to a combination of stresses caused by economic deprivation, urban living, and perceived discrimination, which might push some to resort to violence in interpersonal relations, a phenomenon referred to as the “culture of exasperation.” Kubrin and Weitz [

30] add that neighbourhoods with higher rates of dilapidation and deviance are more likely to be stigmatized.

The crime rate seemed to be higher in poorly supervised areas, namely, areas with a high population turnover, areas with a concentration of dilapidated buildings, and non-residential areas. Respondents were also more likely to link crime with night time.

4.5. Perception of Safety

Although residents felt that the crime rate in Bormla was high in comparison to other areas, they felt safe. Perception of safety is linked to place, as demonstrated above. This perception of safety was influenced by age, marital status, gender and time. Certain areas were perceived as highly unsafe by some of the residents, especially areas where public use of the area was uni-directional. Only seven out of the 317 respondents felt unsafe “kull imkien” (everywhere) in Bormla, and this fear emanated “minhabba d-drogi” (because of drug-related crime).

In spite of the high population turnover in Bormla [

7], the data demonstrates that there was still a high degree of collective efficacy. This level of collective efficacy was more prevalent in areas where residents had been living for a number of years. Sampson

et al. [

21] refer to collective efficacy as the neighbours’ effort to look out for each other. This level of safety was attained when residents looked out for their family’s and neighbours’ interests. Kaplan

et al. [

31] maintain that there is a correlation between collective efficacy, social cohesion, and income inequality.

5. Conclusions

This article looked at the rate and type of crime that took place in Bormla in the period between 2009 and 2010. Respondents felt that the rate and the type of crime cited by the authorities did not concur with their own experience of antisocial behaviour. At the same time, a good number of crime hotspots underpinned by administrative data were also identified by respondents in the needs assessment exercise.

The crime patterns which emerged in the analysis of official statistics were not always in keeping with how community members experienced crime in this location. While both law enforcers and a sample of community members agreed that crime was more likely to take place in spaces with unilateral usage, areas with a concentration of uninhabited and derelict buildings, and areas experiencing constant population turnover, they were less likely to agree on the extent and type of crime that took place in these areas. It was also evident that community members were concerned about crime against the person, while police authorities were more likely to act on reports of crime against property.

A sample of the Bormla community felt that the high crime rate in this locality was mainly caused by social dumping, coupled with a low police response rate. Statistics demonstrate that there was a high concentration of ex-offenders living within the locality, specifically in the so-called “poverty hotspots” indicated by the maps, which were incidentally also the areas with a high concentration of crime. This means that, to some extent, official statistics give some credence to the community’s perception that “outsiders” were the problem, although not all crime could be laid at their door.