Banishment in Public Housing: Testing an Evolution of Broken Windows

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Banishment in Public Housing

2.2. Policing and Banishment in Kings Housing Authority

- Enforcement of banishment and use of community policing in KHA was a process dating to 1995 when the local police department adopted its own KHA community policing initiative. After a department-wide request for officers to participate, eight were chosen and each assigned to one of the eight neighborhoods. One sergeant heads the KHA community policing unit and reports to a precinct captain, bypassing a lieutenant. KHA public housing officers (PHOs) have no assigned shifts and are given their own discretion as to how they want to fulfil their required work hours. However, supervisors strongly encourage PHOs to work hours typically associated with higher levels of crime (i.e., nights and weekends), and PHOs are encouraged to work longer than the department minimum eight-and-a-half hour shift.

- KHA’s community policing crime enforcement strategy extends beyond assigned communities and flexible schedules. PHOs utilize geographic crime statistics to report to their sergeant about trends and patterns of crime within their assigned neighborhoods. The crime statistics are also used for follow-up investigations with residents, to problem-solve emerging criminal issues, and to establish responsibility for a PHOs community. When on the street, PHOs are also given discretion as to how they choose to patrol: vehicle patrol, bicycle patrol, or foot patrol. PHOs are expected to handle only calls for service in public housing and nowhere else during their shifts. Finally, PHOs are given work cell phones, provided by KHA, to allow for residents to call them for non-emergencies.

- KHA PHOs work closely with KHA security and KHA property managers as well. First, when either of these parties encounters residents violating their lease or involved in crime, an Incident Report is generated and communicated amongst these groups. Should non-PHOs encounter lease violations or crime among residents while PHOs are not available, they may communicate the issue with the appropriate PHO who would determine if an Incident Report is necessary. KHA property managers then hold monthly grounds to appear (GTA) meetings with residents involved in Incident Reports. During GTA meetings, KHA security, KHA property managers, and PHOs all collectively review the incident with the resident to determine whether some action against the resident will be taken. The possible actions range from a warning to lease cancellation.

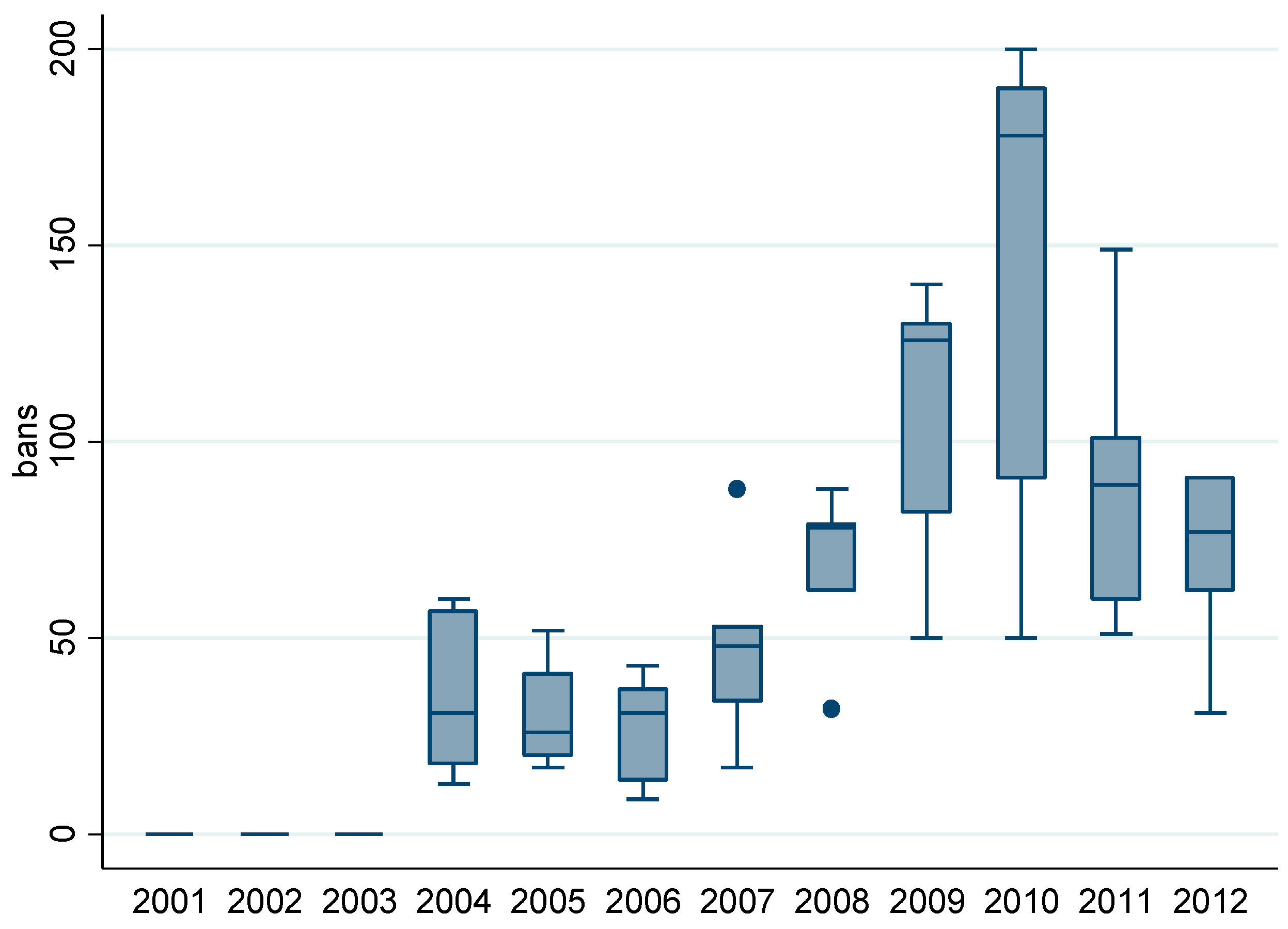

- During the early years of the community policing program in KHA, PHOs concluded that the majority of the problems plaguing their neighborhoods involved non-residents [33]. Through guidance of the local judge, PHOs were able to establish the initial criteria to begin its enforcement of trespassing, to include: posting visible no-trespass signs; giving a warning to a non-resident on their first encounter; having prior knowledge a non-resident has been given warning before arresting them for trespassing; [and warning residents that the KHA PHOs would begin enforcing banishment] [33]. It was not until suspects began to contest trespassing charges, stating they were never issued a warning to stay off the property, that the local courts mandated the police department and KHA to begin utilizing a formal ban notice. The formal use of banishment began in 2004.

- The procedure for issuing, maintaining, and enforcing ban notices on public housing property is similar to what has been detailed in the literature (see [21,31,34,35]). First, ‘non-residents who are discovered on any KHA property and who engage in [activities punishable by banishment] will be determined to be trespassers and will receive a written trespass notice banning them from the premises’ [36]. After an individual has been issued a ban notice, the person is then entered into a no-trespass list maintained by the police department, specifically by KHA PHOs, and updated bimonthly. If the person is caught back on the property, they can then be arrested for trespassing. While PHOs maintain full responsibility for the enforcement of banishment, non-PHOs are trained in enforcing banishment in the event PHOs are not available [33].

- Like other cities, the criteria for banning are broad [21]. Any non-resident involved in any crime on KHA property can be banned. Non-criminal activity on the property that qualifies for banishment includes: grouping for the purpose of threatening or intimidating; ‘prior involvement of narcotic activity/violations’; not demonstrating a legitimate business or social purpose for being on the premises; and ‘engaging in any conduct which interferes with the enjoyment of the premises by adversely affecting the health safety, or welfare of residents, guests, employees, communities, and/or properties of [KHA]’ [36]. Once a ban notice is served to a non-resident, it is effective at that time and “remains in effect indefinitely” [36]. Furthermore:If such non-resident maintains that he or she is a guest or invitee of a resident of KHA property, a copy of this notice will also be served upon the tenant via mail, hand-delivery, or by posting it on the door at the tenant’s last known place of residence.[36]

- Notification of an individual banned may also be discussed with the tenant at GTA meetings [36]. Leases may be terminated should banned individuals return to the property with the tenant’s consent or knowledge.

- However, appealing banishment is allowed in this city under some guidelines. The head of household that the banned individual was visiting are the only person that can appeal a ban notice. An appeal process begins with the head of household contacting the head of KHA security and stating they want to appeal a ban notice [33]. Furthermore, ‘such an appeal must be in writing and filed within ten days of receipt of the ban notice’ [36]. Appeals are not applicable to: (1) any criminal activity that threatens the health, safety, or right to peaceful enjoyment of the premises of other tenants or employees of the authority; (2) any violent or drug-related criminal activity on or off the premises; (3) disputes between tenants; or (4) ‘class grievances’ [35]. Should KHA security decided to lift the ban, the head of household is notified, and KHA PHOs are advised to remove the banned individual from the ban list. Finally, while the information for appeal appears on the back of the ban notice, officers (PHOs and non-PHOs) routinely inform banned individuals verbally the steps in making an appeal when issuing ban notices [33].

2.3. Broken Windows

2.4. Banishment and Broken Windows

3. Method

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Models

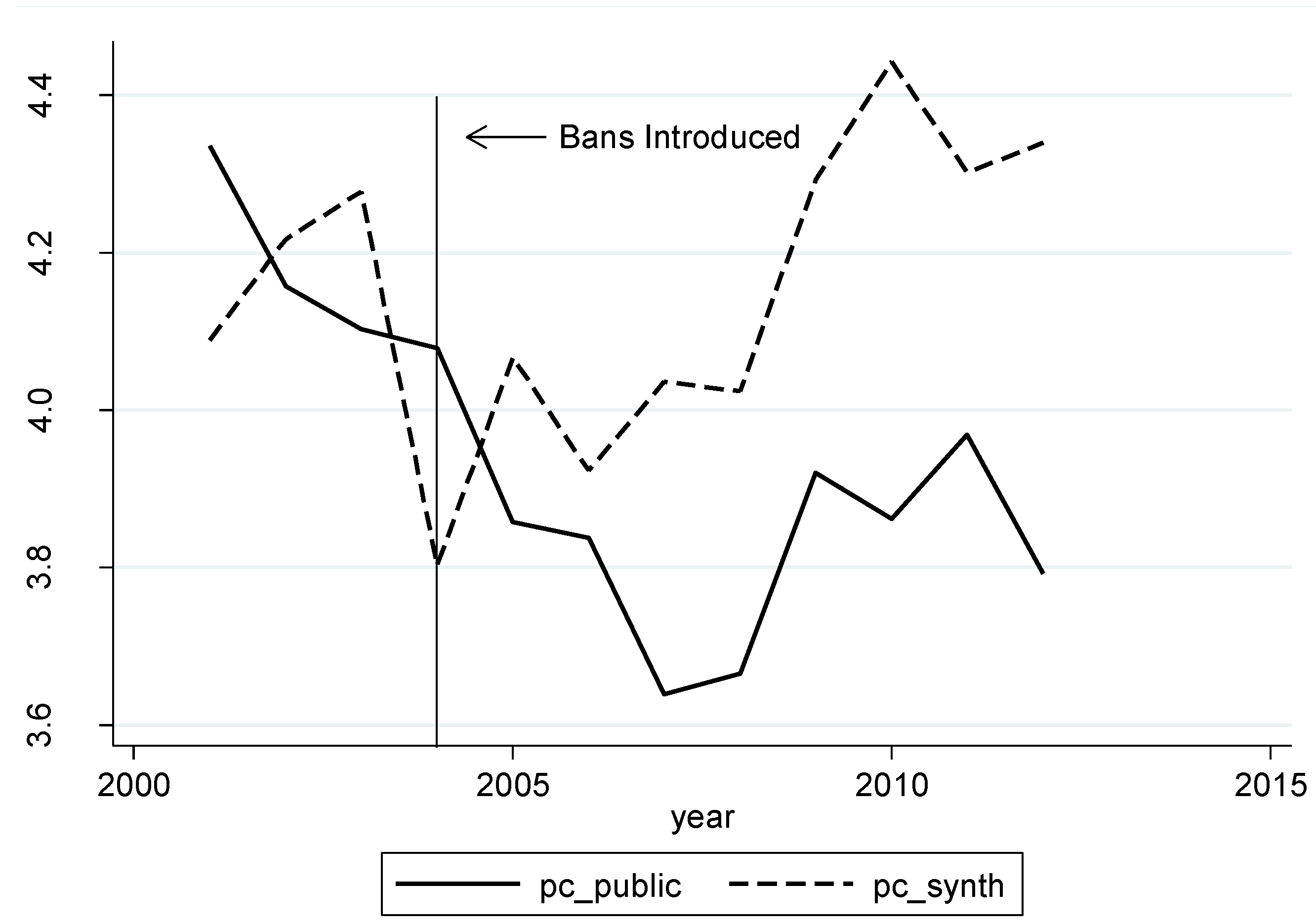

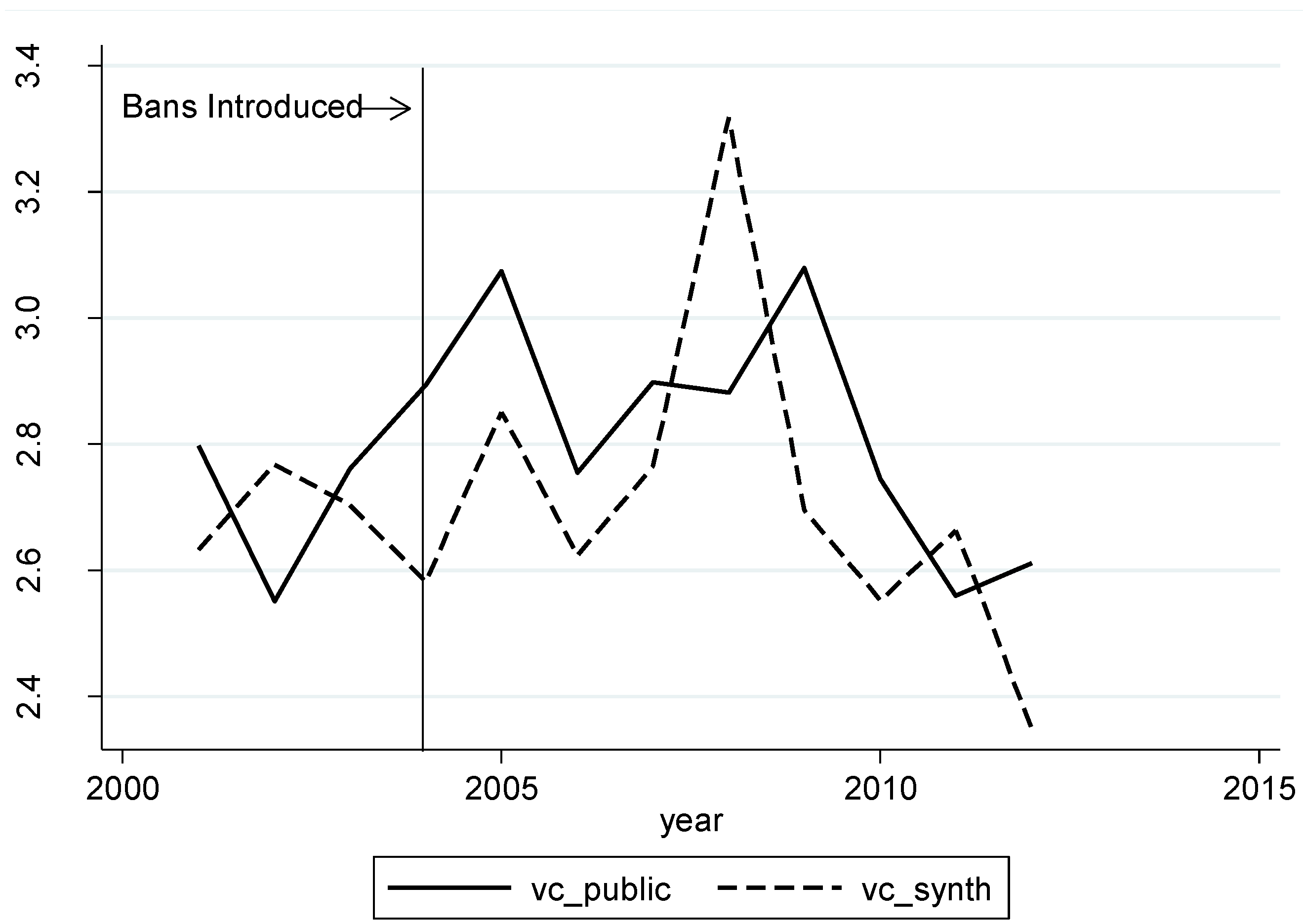

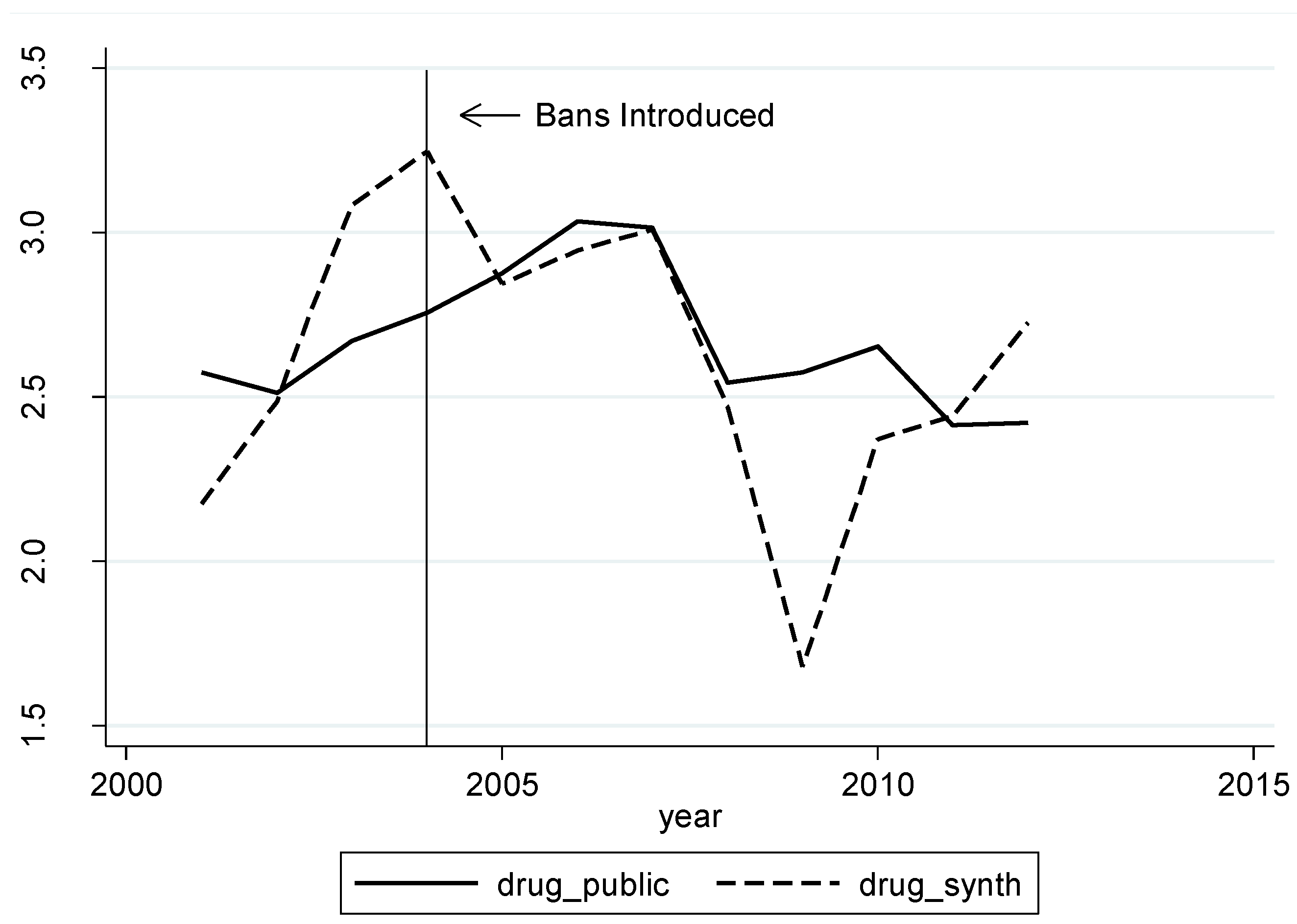

4. Results

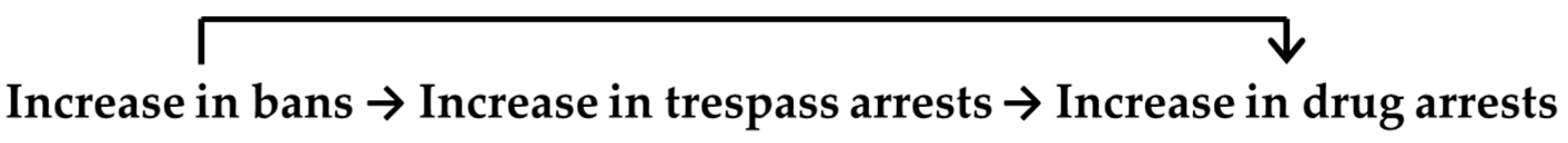

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References and Notes

- James Q. Wilson, and George Kelling. “The Police and Neighborhood Safety: Broken Windows.” Atlantic Monthly. 1982. Available online: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1982/03/broken-windows/304465/ (accessed on 4 August 2014).

- William Bratton, and Peter Knobler. The Turnaround: How America’s Top Cop Reversed the Crime Epidemic. New York: Random House, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot Spitzer. “The New York City Police Department’s ‘Stop and Frisk’ Practices.” Office of the New York State Attorney General. 1999. Available online: www.oag.state.ny.us/press/reports/stop _frisk/stop_frisk.html (accessed on 30 August 2014).

- George L. Kelling, and Catherine Cole. Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities. New York: Martin Kessler Books, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eli Silverman. The NYPD Battles Crime: Innovative Ideas in Policing. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard E. Harcourt. Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Katherine Beckett, and Steven Kelly Herbert. Banished: The New Social Control in Urban America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Annan O. Sampson, and Wesley G. Skogan. Drug Enforcement in Public Housing: Signs of Success in Denver. Washington: Police Foundation, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lorraine Green Mazerolle, and William Terrill. “Problem-oriented policing in public housing: Identifying the distribution of problem places.” Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 20 (1997): 235–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack R. Greene, Alex R. Piquero, Patricia Collins, and Robert J. Kane. “Doing research in public housing: Implementation issues from Philadelphia’s 11th street corridor community policing program.” Justice Research and Policy 1 (1999): 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmund F. McGarrell, Andrew L. Giacomazzi, and Quint C. Thurman. “Reducing disorder, fear, and crime in public housing: A case study of place-specific crime prevention.” Justice Research and Policy 1 (1999): 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan J. Popkin, Victoria E. Gwiasda, Dennis P. Rosenbaum, Jean M. Amendolia, Wendell A. Johnson, and Lynn M. Olson. “Combating crime in public housing: A qualitative and quantitative longitudinal analysis of the Chicago Housing Authority’s anti-drug initiative.” Justice Quarterly 16 (1999): 519–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert J. Kane. “Permanent beat assignments in association with community policing: Assessing the impact on police officers’ field activity.” Justice Quarterly 17 (2000): 259–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William F. Walsh, Gennaro F. Vito, Richard Tewksbury, and George P. Wilson. “Fighting back in Bright Leaf: Community policing and drug trafficking in public housing.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 25 (2000): 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John W. Barbrey. “Measuring the effectiveness of crime control policies in Knoxville’s public housing using mapping software to filter Part I crime data.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 20 (2004): 6–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey Fagan, Garth Davies, and Jan Holland. “The paradox of the Drug Elimination Program in New York City public housing.” Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy 13 (2006): 415–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey Fagan, Garth Davies, and Adam Carlis. “Race and selective enforcement in public housing.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 9 (2012): 697–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose Torres. “Predicting Perceived Police Effectiveness in Public Housing: Police Contact, Police Trust, and Police Responsiveness.” Policing and Society. 2015. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1077837 (accessed on 4 August 2014).

- Department of Housing and Urban Development v. Rucker, 535 U.S. 125, 122 S. Ct. 1230, 152 L. Ed. 2d 258 (2002).

- Robert A. Graham, Lisa Walker, William F. Maher, Ricardo L. Gilmore, and Raymond K. James. “Brief of Amici Curiae Council of Large Public Housing Authorities, Housing and Development Law Institute, Housing Authority Risk Retention Group, National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials, National Organization Of African-Americans in Housing, and Public Housing Authorities Directors Association.” 2003. Available online: http://www.phada.org/amicus03.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2016).

- Elena Goldstein. “Kept out: Responding to public housing no-trespass policies.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Journal 38 (2003): 215–45. [Google Scholar]

- Captain C. G. Hunter, and Judi Frist-Riutort. “No-Trespassing.” Problem Solving Quarterly 2 (1989): 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly E. O’Leary. “Dialogue, perspective and point of view as lawyering method: A new approach to evaluating anti-crime measures in subsidized housing.” Washington University Journal of Urban & Contemporary Law 49 (1996): 133–214. [Google Scholar]

- Papachristou v. Jacksonville, 405 U.S. 156, 92 S. Ct. 839, 31 L. Ed. 2d 110 (1972).

- Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87, 86 S. Ct. 211, 15 L. Ed. 2d 176 (1965).

- Commonwealth v. Hicks, 563 SE 2d. 674 Va: Supreme Court, (2002).

- Allen Park Housing Commission. “Trespass Policy.” Michigan: Allen Park, 2014, Available online: http://allenparkhousing.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Trespass-Policy.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2014).

- Charlotte Housing Authority. “Limited Access and Banning Policy and Procedures.” 2014. Available online: http://www.cha-nc.org/documents/BANNING%20POLICY%20AND%20PROCEDURES%20-%20Appendix%20J.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2014).

- Portsmouth Housing Authority. “Portsmouth Redevelopment Housing Authority Trespass-Barment Policy.” 2014. Available online: http://www.prha.org/prha/images/documents/home/Trespass%20Barment%20Policy.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2014).

- Winder Housing Authority. “Trespass and Barring Policy of the Housing Authority of the City Of Winder.” 2014. Available online: http://www.winderhousing.com/policies/Trespass-and-Ban-policy-of-WHA.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2014).

- Gary A. Beck. “Ban lists: Can public housing authorities have unwanted visitors arrested? ” University of Illinois Law Review 24 (2004): 1223–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mary M. Cheh. “Constitutional limits on using civil remedies to achieve criminal law objectives.” Hastings Law Journal 42 (1991): 1325–48. [Google Scholar]

- Captain John Doe (Kings Housing Authority). Interview, 2013.

- Adam Carlis. “The illegality of vertical patrols.” Columbia Law Review 109 (2009): 2002–43. [Google Scholar]

- Don Mitchell. “Property rights, the first amendment, and judicial anti-urbanism: The strange case of Virginia v. Hicks.” Urban Geography 26 (2005): 565–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kings Housing Authority Security Managers Office. “KHA Trespass/Ban Policy.” Hanford, CA, USA: Kings Housing Authority Security Managers Office, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wesley G. Skogan. Disorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoods. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Micelle Alexander. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Amanda Geller, and Jeffrey Fagan. “Pot as pretext: Marijuana, race, and the new disorder in New York City street policing.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 7 (2010): 591–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott Levy. “The collateral consequences of seeking order through disorder: New York’s narcotics eviction program.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 43 (2008): 539–80. [Google Scholar]

- Janet Smith. “Public Housing Transformation: Evolving National Policy.” In Where are Poor People to Live?: Transforming Public Housing Communities. Edited by Larry Bennett, Janet L. Smith and Patricia Wright. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2006, pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth Griffiths, and George Tita. “Homicide in and around public housing: Is public housing a hotbed, a magnet, or a generator of violence for the surrounding community? ” Social Problems 56 (2009): 474–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolás Medina Mora. “NYPD Tells Cops To Stop Questioning People Just For Hanging Out In Housing Projects.” BuzzFeed News. 16 March 2015. Available online: https://www.buzzfeed.com/nicolasmedinamora/nypd-will-no-longer-stop-people-just-for-being-present-in-pu?utm_term=.kvDD5K3oA#.jdGBLbgDP (accessed on 10 February 2016).

- William Stuntz. “Privacy’s problem and the law of criminal-procedure.” Michigan Law Review 93 (1995): 1016–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony A. Braga, Brandon C. Welsh, and Cory Schnell. “Can policing disorder reduce crime? A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 52 (2015): 567–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Rosenfeld, Robert Fornango, and Andres F. Rengifo. “The impact of order-maintenance policing on New York City homicide and robbery rates: 1988–2001.” Criminology 45 (2007): 355–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Rosenfeld, and Robert Fornango. “The impact of police stops on precinct robbery and burglary rates in New York City, 2003–2010.” Justice Quarterly 31 (2014): 96–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth Land, Patricia McCall, and Lawrence Cohen. “Structural covariates of homicide rates: Are there any invariances across time and space? ” American Journal of Sociology 95 (1990): 922–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James Hawdon, and John Ryan. “Social capital, social control and crime.” Crime and Delinquency 55 (2009): 526–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen F. Parker, Brian J. Stults, and Stephen K. Rice. “Racial threat, concentrated disadvantage and social control: Considering the macro-level sources of variation in arrests.” Criminology 43 (2005): 1111–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert J. Sampson, and Dawn Jeglum Bartusch. “Legal cynicism and (subcultural?) tolerance of deviance: The neighborhood context of racial differences.” Law & Society Review 32 (1998): 777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert J. Sampson, Stephen W. Raudenbush, and Felton Earls. “Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy.” Science 277 (1997): 918–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau. “2000 U.S Census.” 2014. Available online: http://factfinder.census.gov/ (accessed on 20 September 2014). [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. “2010 U.S Census.” 2014. Available online: http://factfinder.census.gov/ (accessed on 20 September 2014). [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. “2008–2012 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.” 2014. Available online: http://factfinder.census.gov/ (accessed on 20 September 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Rodney Stark. “Deviant places: A theory of the ecology of crime.” Criminology 25 (1987): 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey D. Morenoff, and Robert J. Sampson. “Violent crime and the spatial dynamics of neighborhood transition: Chicago, 1970–1990.” Social Forces 76 (1997): 31–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Roodman. “How to do Xtabond2: An Introduction to Difference and System GMM in Stata.” Center for Global Development Working Paper No. 103; Washington, DC, USA: Center for Global Development, December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Decker, Richard Wright, and Robert Logie. “Perceptual deterrence among active residential burglars: A research note.” Criminology 31 (1993): 135–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross L. Matsueda, Derek A. Kreager, and David Huizinga. “Deterring delinquents: A rational choice model of theft and violence.” American Sociological Review 71 (2006): 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex Piquero, and George F. Rengert. “Studying deterrence with active residential burglars.” Justice Quarterly 16 (1999): 451–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David P. Farrington, and Donald J. West. The Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development: A Long-Term Follow-Up of 411 London Males. Berlin: Springer, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- David Farrington, Alex R. Piquero, and Wesley G. Jennings. Offending from Childhood to Late Middle Age: Recent Results from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin E. Wolfgang, Robert M. Figlio, and Thorsten Sellin. Delinquency in a Birth Cohort. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- David Kennedy. “Violence and street groups: Gangs, groups, and violence.” In The Causes and Consequences of Group Violence. Edited by James Hawdon, John Ryan and Marc Lucht. New York: Lexington, 2014, pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew V. Papachristos. “Murder by structure: Dominance relations and the social structure of gang homicide.” American Journal of Sociology 115 (2009): 74–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott H. Decker. “Collective and normative features of gang violence.” Justice Quarterly 13 (1996): 243–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Kennedy. “Pulling levers: Chronic offenders, high-crime settings, and a theory of prevention.” Valparaiso University Law Review 31 (1997): 449–84. [Google Scholar]

- David Kennedy. Deterrence and Crime Prevention: Reconsidering the Prospect of Sanction. London: Routledge Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony A. Braga, and David L. Weisburd. “The effects of ‘pulling levers’ focused deterrence strategies on crime.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 6 (2012): 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rod K. Brunson. “Focused deterrence and improved police–community relations.” Criminology & Public Policy 14 (2015): 507–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas Corsaro, and Robin S. Engel. “Most challenging of contexts.” Criminology & Public Policy 14 (2015): 471–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew V. Papachristos, Tracey L. Meares, and Jeffrey Fagan. “Attention felons: Evaluating Project Safe Neighborhoods in Chicago.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 4 (2007): 223–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony Braga. “Getting deterrence right? ” Criminology & Public Policy 11 (2012): 201–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corinne Ramey. “Permanent-Ban Policy in Public Housing under Review.” The Wall Street Journal. 27 May 2016. Available online: http://www.wsj.com/articles/permanent-ban-policy-in-public-housing-under-review-1464343201 (accessed on 1 June 2016).

- American Civil Liberties Union. “Families Untied: Public Housing Banning Policy Tears Families Apart.” YouTube. 2009. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wHFCUr_Lc6s (accessed on 10 January 2015).

- Michael Tonry. Punishing Race: A Continuing American Dilemma. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Loïc Wacquant. Deadly Symbiosis: Race and the Rise of the Penal State. Cambridge: Polity, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robert D. Baller, Luc Anselin, Steven F. Messner, Glenn Deane, and Darnell F. Hawkins. “Structural covariates of U.S. county homicide rates: Incorporating spatial effects.” Criminology 39 (2003): 561–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacqueline Cohen, and George Tita. “Diffusion in homicide: Exploring a general method for detecting spatial diffusion processes.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 15 (1999): 451–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven F. Messner, Luc Anselin, Robert D. Baller, Darnell F. Hawkins, Glenn Deane, and Stewart E. Tolnay. “The spatial patterning of county homicide rates: An application of exploratory spatial data analysis.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 15 (1999): 423–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert J. Sampson, and Stephen W. Raudenbush. Disorder in Urban Neighborhoods: Does It Lead to Crime; Washington: US Department of Justice, 2001.

- David Weisburd, Shawn Bushway, Cynthia Lum, and Sue-Ming Yang. “Trajectories of crime at places: A longitudinal study of street segments in the city of Seattle.” Criminology 42 (2004): 283–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert T. Guerette, and Kate J. Bowers. “Assessing the extent of crime displacement and diffusion of benefits: A review of situational crime prevention evaluations.” Criminology 47 (2009): 1331–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevor Bennett, and Richard Wright. Burglars on Burglary: Prevention and the Offender. Brookefield: Gower, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- P. Jeffrey Brantingham, and Patricia Brantingham. Environmental Criminology. Beverly Hills: Sage, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- John E. Eck. “The threat of crime displacement.” Criminal Justice Abstracts 25 (1993): 527–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wim Bernasco, and Paul Nieuwbeerta. “How do residential burglars select target areas?: A new approach to the analysis of criminal location choice.” British Journal of Criminology 45 (2005): 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wim Bernasco, and Richard Block. “Where offenders choose to attack: A discrete choice model of robberies in Chicago.” Criminology 47 (2009): 93–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wim Bernasco. “Modeling micro-level crime location choice: Application of the discrete choice framework to crime at places.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 26 (2010): 113–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane D. Johnson, and Lucia Summers. “Testing ecological theories of offender spatial decision making using a discrete choice model.” Crime & Delinquency 61 (2015): 454–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert J. Kane. “Policing in public housing: Using calls for service to examine incident-based workload in the Philadelphia Housing Authority.” Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 21 (1998): 618–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1KHA is a pseudonym for the actual PHA used for this and the Torres [18] study.

- 3Banishment has been used on public and private property, residential and business properties, and areas handpicked by local judges [7].

- 4As a result of the National Commission on Severely Distressed Public Housing, Congress created HOPE VI, which called for many of the nation’s public housing communities to undergo physical revitalizations or be demolished altogether (see [41]).

- 5As of 2016, only the NYPD has publicly denounced the practice of stopping anyone in public housing under the guise of a trespass investigation (see [43]).

| Neighborhood | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Housing 1 | Bans | 57 | 20 | 43 | 88 | 79 | 140 | 178 | 101 | 91 |

| (32%) | (13%) | (32%) | (37%) | (23%) | (27%) | (25%) | (22%) | (26%) | ||

| Pop. | 1715 | 1732 | 1749 | 1766 | 1783 | 1800 | 1817 | 1834 | 1851 | |

| Public Housing 2 | Bans | 31 | 41 | 37 | 48 | 78 | 130 | 190 | 149 | 91 |

| (17%) | (26%) | (28%) | (20%) | (23%) | (25%) | (27%) | (33%) | (26%) | ||

| Pop. | 1939 | 1950 | 1961 | 1973 | 1984 | 1995 | 2006 | 2018 | 2029 | |

| Public Housing 3 | Bans | 13 | 17 | 14 | 34 | 88 | 82 | 91 | 51 | 77 |

| (7%) | (11%) | (10%) | (14%) | (26%) | (16%) | (13%) | (11%) | (22%) | ||

| Pop. | 852 | 858 | 865 | 871 | 878 | 884 | 891 | 897 | 904 | |

| Public Housing 4 * | Bans | 60 | 52 | 31 | 53 | 62 | 126 | 200 | 89 | 62 |

| (34%) | (33%) | (23%) | (22%) | (18%) | (24%) | (28%) | (20%) | (18%) | ||

| Pop. | 2216 | 2216 | 2216 | 2217 | 2217 | 2217 | 2217 | 2217 | 2217 | |

| Public Housing 5 | Bans | 18 | 26 | 9 | 17 | 32 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 31 |

| (10%) | (17%) | (7%) | (7%) | (9%) | (9%) | (7%) | (13%) | (9%) | ||

| Pop. | 1252 | 1247 | 1243 | 1238 | 1234 | 1229 | 1224 | 1220 | 1215 | |

| Public Housing Total | Bans | 179 | 156 | 134 | 240 | 339 | 528 | 709 | 450 | 352 |

| (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | ||

| Pop. | 7974 | 8003 | 8034 | 8065 | 8096 | 8125 | 8155 | 8186 | 8216 |

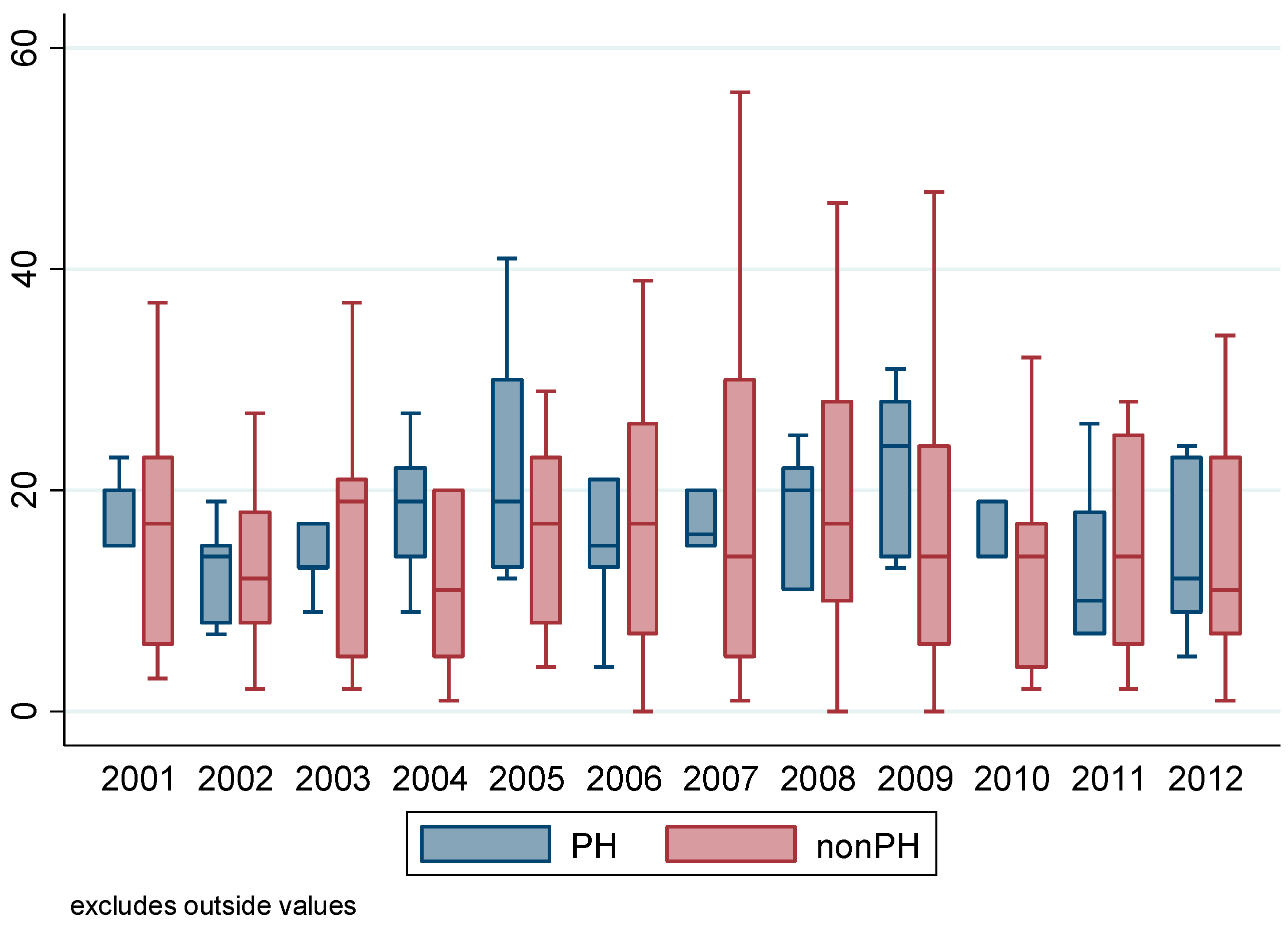

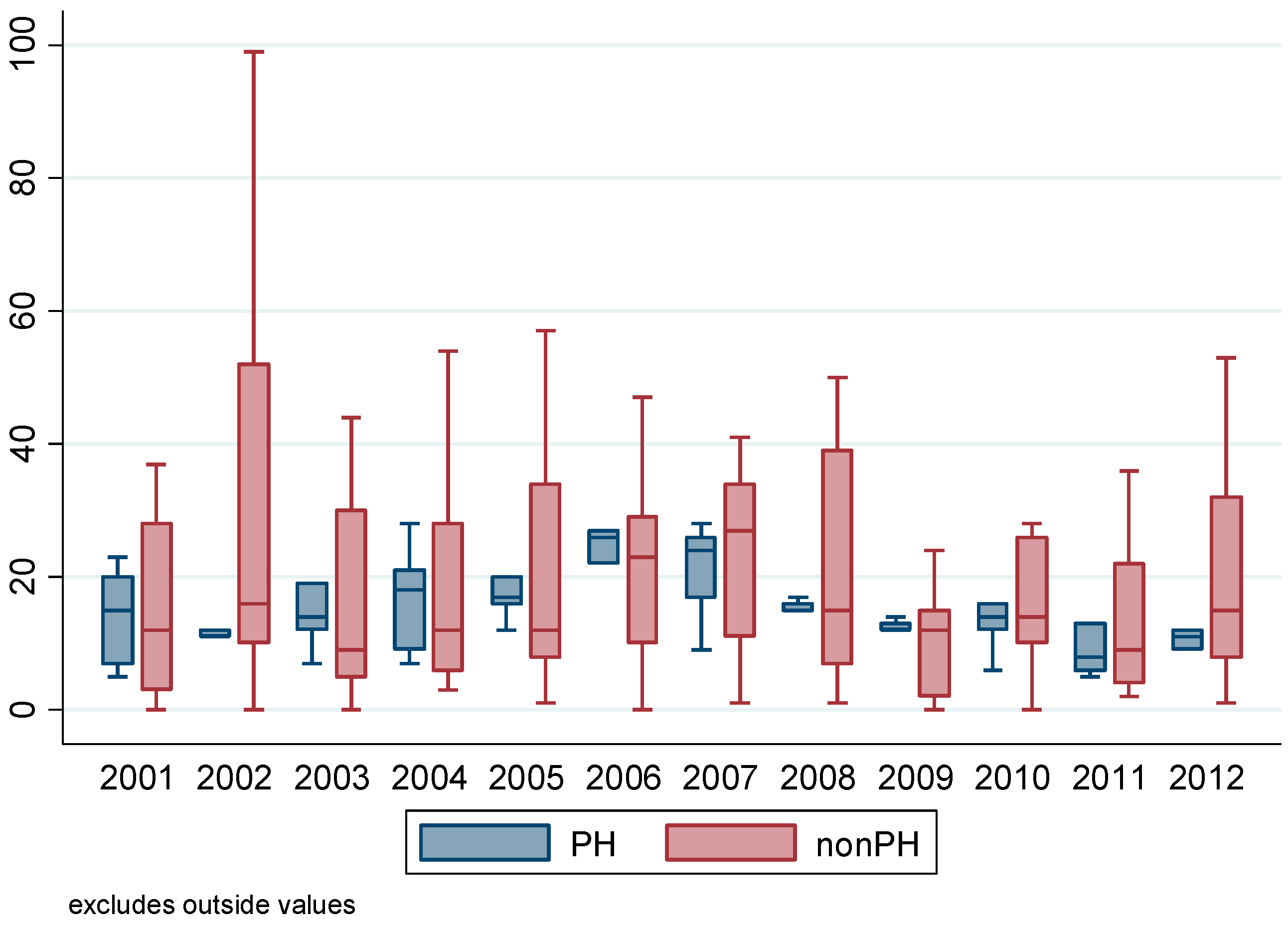

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Property Crime | Overall | 100.6 | 134.8 | 16.0 | 776.0 |

| Between | 136.5 | 27.5 | 631.4 | ||

| Within | 21.9 | 32.2 | 245.2 | ||

| Violent Crime | Overall | 17.4 | 12.8 | 0.0 | 64.0 |

| Between | 11.7 | 1.9 | 44.1 | ||

| Within | 5.8 | –5.3 | 37.9 | ||

| Trespass Arrest | Overall | 11.7 | 22.0 | 0.0 | 194.0 |

| Between | 17.5 | 1.2 | 72.3 | ||

| Within | 13.9 | –25.2 | 165.8 | ||

| Drug Arrest | Overall | 20.6 | 23.1 | 0.0 | 174.0 |

| Between | 18.5 | 1.2 | 77.5 | ||

| Within | 14.4 | –44.9 | 117.1 | ||

| Concentrated Disadvantage | Overall | 0.0 | 1.0 | –2.1 | 1.7 |

| Between | 1.0 | –2.1 | 1.5 | ||

| Within | 0.2 | –0.6 | 0.6 |

| Effect/Model | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Property Crime(t-1) | 0.274 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.288 ** |

| (0.089) | (0.094) | (0.100) | |

| Bans(t-1) | –0.054 * | –0.083 * | –0.076 * |

| (0.024) | (0.032) | (0.033) | |

| Concentrated Disadvantage | –0.011 | –0.019 | |

| (0.330) | (0.345) | ||

| Year | 0.009 | 0.008 | |

| (0.018) | (0.019) | ||

| Trespass Arrests(t-1) | –0.015 | ||

| (0.039) | |||

| Drug Arrests(t-1) | –0.053 | ||

| (0.052) | |||

| N | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| n | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Wald chi-square | 19.9 ** | 43.0 ** | 46.4 ** |

| Effect/Model | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Violent Crime(t-1) | 0.247 | 0.077 | 0.025 |

| (0.153) | (0.085) | (0.097) | |

| Bans(t-1) | 0.013 | 0.053 | 0.053 |

| (0.029) | (0.047) | (0.044) | |

| Concentrated Disadvantage | 0.139 | 0.119 | |

| (0.452) | (0.413) | ||

| Year | –0.009 | –0.004 | |

| (0.024) | (0.022) | ||

| Trespass Arrests(t-1) | –0.047 | ||

| (0.030) | |||

| Drug Arrests(t-1) | 0.102 | ||

| (0.066) | |||

| N | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| n | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Wald chi-square | 3.5 | 3.2 | 15.8 * |

| Effect/Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trespass Arrests(t-1) | 0.196 | 0.337 | 0.272 | 0.242 |

| (0.228) | (0.206) | (0.188) | (0.159) | |

| Bans(t-1) | 0.116 | –0.077 | ||

| (0.096) | (0.084) | |||

| Bans(t-2) | 0.248 ** | 0.106 † | ||

| (0.083) | (0.061) | |||

| Concentrated Disadvantage | 0.012 | 0.711 | ||

| (0.771) | (0.471) | |||

| Year | 0.079 | 0.081 ** | ||

| (0.050) | (0.025) | |||

| N | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| n | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Wald chi-square | 3.7 | 27.3 ** | 13.0 ** | 63.0 ** |

| Effect/Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Arrests(t-1) | 0.159 | 0.132 | 0.086 | 0.164 | 0.087 | 0.090 |

| (0.131) | (0.155) | (0.136) | (0.143) | (0.134) | (0.136) | |

| Bans(t-1) | –0.084 | 0.026 | 0.044 | |||

| (0.075) | (0.041) | (0.045) | ||||

| Bans(t-2) | –0.044 | 0.084 † | 0.097 * | |||

| (0.084) | (0.044) | (0.048) | ||||

| Concentrated Disadvantage | –0.261 | –0.348 | –0.444 | –0.445 | ||

| (0.748) | (0.444) | (0.399) | (0.408) | |||

| Year | –0.041 | –0.051 † | –0.062 * | –0.064 * | ||

| (0.037) | (0.030) | (0.027) | (0.029) | |||

| Trespass Arrests(t-1) | 0.022 | 0.028 | ||||

| (0.071) | (0.071) | |||||

| Trespass Arrests(t-2) | –0.014 | –0.020 | ||||

| (0.057) | (0.058) | |||||

| N | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| n | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Wald chi-square | 2.8 | 9.9 * | 12.7 * | 2.1 | 10.5 * | 13.3 * |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres, J.; Apkarian, J.; Hawdon, J. Banishment in Public Housing: Testing an Evolution of Broken Windows. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040061

Torres J, Apkarian J, Hawdon J. Banishment in Public Housing: Testing an Evolution of Broken Windows. Social Sciences. 2016; 5(4):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040061

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres, Jose, Jacob Apkarian, and James Hawdon. 2016. "Banishment in Public Housing: Testing an Evolution of Broken Windows" Social Sciences 5, no. 4: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040061

APA StyleTorres, J., Apkarian, J., & Hawdon, J. (2016). Banishment in Public Housing: Testing an Evolution of Broken Windows. Social Sciences, 5(4), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5040061