1. Introduction

The U.S. immigrant population is approximately 40 million (

U.S. Census Bureau 2011), driven by Hispanic population growth (

Abascal 2015). As a result, immigration is a significant policy concern. However, efforts to produce comprehensive immigration reform have been stymied due in part to a vocal minority of Americans opposed to immigration outmuscling a relatively indifferent majority of Americans who support specific measures to address immigration. In a democracy, if public opinion is a guide to policymakers, then it is important to understand the sources of discord in public opinion on this very salient issue. Therefore, we ask: why do some Americans support immigration and others do not? The purpose of this article is to answer this question using social identity theory as the platform for explaining why some Americans support or oppose legal immigration and why some Americans support or oppose increased spending to slow the flow of illegal immigration into the United States.

The American public undoubtedly considers other factors when rendering their preferences for or against increased immigration and spending to curb illegal immigration. To be sure, the evidence that demonstrate a relationship between cultural threat and economic threat is neither clear nor consistent.

Hainmueller and Hopkins (

2015) find that Americans’ opinions do not vary much according to cultural concerns or their personal characteristics. They conclude that limits exist on theories based on cultural and economic threats. Hence, we seek to assess the robustness of national identity by applying social identity theory. We add to the studies that move beyond the discussion of cultural and economic considerations to explore a multidimensional construct of the perceived importance of citizens’ acceptance of an American identity as a predictor of his or her opinions on immigration. To explore this possibility, we utilize social identity theory (

Tajfel and Turner 1979) because this theory captures the dynamics of intragroup cohesion and intergroup differences (

Brown 2001;

Callero 2015;

Hogg 2016;

McLeod 2008;

Tajfel 2010) that we believe depict how the American public thinks about immigration. Therefore, this article constructs a social identity model of American identity (identification as American or characteristics that foster feeling American) and applies it to public opinion towards immigration.

We believe that social identity dynamics are at play when the issue of immigration arises. That is, we submit that immigration attitudes are shaped, at least in part, by conceptions regarding in-groups and out-groups being able (if not willing) to espouse an American Identity. For instance,

Schildkraut (

2005) finds that a significant portion of anti-immigrant sentiment can be explained by perceptions among the majority about whether immigrants want to become American, and whether they seek to blend into U.S. society. Moreover, our understanding of social identity theory suggests that individuals who adopt an American identity will place those they believe do not have an American identity in the out-group. As a result, a favorability gap exists between those they believe share with them an American identity over those they believe do not share an American identity. That is, there is greater affinity for those they believe are in the American identity in-group and less affinity for those who are in the non-American identity out-group. Based on this in-group favorability, they will support policies that benefit the in-group and oppose policies that benefit the out-group. Therefore, people who have an American identity will oppose immigration because immigrants are members of an out-group that they believe do not have an American identity or they do not represent what it means to be a group member.

The aim of this scholarship is two-fold. First, we endeavor to extend understanding of American identity (and consequently how it is measured) as well as how it affects public preferences toward legal immigration and spending to deter illegal immigration. By examining social identity through the concept of an American identity, greater understanding of public opinion towards immigration can be ascertained. Second, we create a more comprehensive and multidimensional measure of American identity that accounts for all aspects of social identity theory. Previous renderings of American identity lacked survey items that prompted respondents to engage in a social comparison. Without a social comparison, social identity is not adequately measured. Therefore, our measure of American identity (in addition to place of birth, thoughts on what it means to be a true American, and patriotism) adds two dimensions to the operationalization of American identity. Those added dimensions are sociopolitical threat posed by those who are not English speakers and sociocultural threat posed by immigrants. Rather than the dichotomous framework in the literature, we submit that American identity has five dimensions. Additionally, these five dimensions address all the features of social identity theory.

To achieve these objectives, we begin with a review of the literature on American identity and public opinion on immigration. Following that discussion, we describe how social identity affects public opinion on immigration. We then discuss our measure of American identity and explain how its several dimensions influence those who identify as such to oppose immigration and to support spending to patrol the border against illegal immigration. Analyses of the data from the 2004–2005 National Politics Survey confirm that Americans do call upon the five dimensions of American identity when forming opinions about immigration. Specifically, the findings reveal that American identity leads to opposition to legal immigration and support for spending increases to combat illegal immigration. We conclude our paper by situating our findings within the ongoing debate over immigration.

2. American Identity and Immigration

A social identity is an individual’s belief that he or she is a member of a particular social group (

Hogg and Abrams 1988) and that belief is derived from comparisons between members of the selected group and other groups (

Stets and Burke 2000). Social identity comprises of belonging to the group, behaving and appearing similar to members of the group, and adopting the group’s viewpoint in place of one’s own. The group itself is a collection of like-minded people who perceive themselves and others in the group similarly, identify with each other, behave alike, and share the same opinions. All these aspects differ from members of other groups (

Stets and Burke 2000).

Social identity theory explains how people perceive themselves as members of a particular social group and how those perceptions influence opinions (

Tajfel 1978;

Tajfel and Turner 1986). The theory entails three major components: social categorization, social identification, and social comparison. Social identity theory proposes that people place themselves in categories or groups. According to the theory, people automatically engage in self-categorization (

Turner et al. 1987). That is, it is natural for people to think in group terms, locating themselves in a social group and believing in the positive aspects of that group. This process of self-categorization coincides with social identification (membership in a group or an affinity the individual has for one group over another). Social identification is a psychological attachment not unlike that of party identification and, also as with party identification, it does not entail a formal procedure for gaining entry into the group (see

Green and Green 1999). The social group in which individuals place themselves is the in-group and other groups are out-groups. Subsequently, people engage in social comparisons, observing differences between their in-group and out-groups. It is also natural for people to think more positively of the in-group and more negatively of the out-group. In-group members create a positive self-identity (

Tajfel 1981). As in-group members, they find their group to be more esteemed, especially regarding a rival out-group. As a result, people create a favorability gap between their well-liked in-group and a disliked out-group.

A few representative works show the influence of American identity on immigration opinions. Much of the focus has been the meaning of what it means to be an American or espouse an American identity.

Citrin et al. (

1990) and

Schildkraut (

2007) provide the basic understanding of the link between American identity and public opinion on immigration. Building on

Citrin et al. (

1990),

Schildkraut (

2007) develops a more comprehensive measure of American identity.

Byrne and Dixon (

2013) also seek an alternative measure of American identity, but still offer a dichotomous presentation. Thus, scholars have transformed the concept of American identity or Americanism from a single index (

Citrin et al. 1990) to a binary understanding (

Schildkraut 2007) to a binary framework with an added dimension (

Byrne and Dixon 2013).

According to

Byrne and Dixon (

2013), a review of the literature suggests that there is no consensus on how American identity is measured, but that it comprises two broad components: ascriptive and affective.

Wright et al. (

2012) address this dichotomy as well. Byrne and Dixon label it the ascriptive component of ethnoculturalism while Wright et al. call it ethnic nationalism. Byrne and Dixon name the affective component civic-republicanism while Wright et al. dub it civic nationalism. The ascriptive features include birthright, religion, language, norms, values, customs, and other cultural considerations (

Byrne and Dixon 2013;

Citrin et al. 1990;

Schildkraut 2007;

Wright 2011;

Wright et al. 2012). Our factor analysis produces two ascriptive dimensions. We label them Born in the USA and Being Truly American. The affective elements include political norms, affinity toward political institutions, and loyalty to the nation. Our factor analysis produces one affective dimension, which we call American Patriotism, which taps into one’s loyalty of nation.

Like Schildkraut (

2007),

Wright (

2011), and

Wright et al. (

2012),

Byrne and Dixon (

2013) examine the impact of ethnoculturalism and find that ethnoculturalism is linked negatively to immigration opinions. Moreover,

Byrne and Dixon (

2013) find that ethnoculturalism is more influential on opinions that immigration should remain at the same level or be decreased. These results are consistent with the literature. Their civic-political dimension is also negatively linked to immigration preferences. Individuals who believe it is important to possess certain traits to be American (speak English, have citizenship, feel and think of oneself as an American, seek economic success, and respect American laws and institutions) are more likely to oppose increases in immigration. Additionally, they observe that their civic-republican dimension mitigates restrictionist policy preferences. Individuals who are engaged about politics (knowledgeable and involved) are less likely to oppose immigration.

Wright et al. (

2012) note that the empirical evidence on ascriptive elements or ethnic nationalism and affective or civic nationalism is mixed. They state that ascriptive or nationalism leads to hostility towards immigrants and opposition to immigration. They suggest that ethnic nationalism leads to greater opposition to immigration because immigrants are vastly different than citizens who are considered natives. In contrast, their findings with respect to civic nationalism (defined here as the ascriptive component of ethnoculturalism) are not consistent. They conclude that civic nationalism is not real or held as deeply or that civic nationalism is a weaker version of ethnic nationalism.

Wright et al. (

2012) are correct to state that the findings for civic nationalism are mixed, but we agree with them for different reasons. We hold that the inconsistencies are due to using dichotomous measures of American identity and ones that do not adequately assess the differences between the two components of ethnic nationalism (ethnoculturalism) and civic nationalism (civic-republicanism). We advance an alternative measure of American identity that provides for a more comprehensive conceptualization and one that has more dimensions. Specifically, our measure allows for considerations of perceived threat, as well as patriotic sentiments and beliefs about being a “true” American.

Relatedly,

Wright (

2011) examines the impact that increasing the numbers of immigrants in a community has on a sense of national identity. He finds that an influx of immigrants leads to the view that they serve as a threat to social harmony and can disrupt the nation’s identity. He also comments that studies that evaluate that relevance of “feeling like a” member of a certain country or living in the country for most of one’s life” are not well placed on either the ethnic or civic nationalism dimensions. Our analyses, however, examine the presence of immigrants as a threat more directly (the impact of immigrants on American ideas and cultures as well as whether people of different racial and ethnic groups should blend into the larger society). Also, we find that place of birth and location of child rearing do fit neatly onto one dimension. Moreover, our measure of American identity includes national symbols and the emotional attachment one has for the nation. That is, our measure of American identity incorporates an American patriotism dimension.

Additionally, the measures of American identity in the literature are limited, for they do not address all the elements of the social identity theory. Our sociopolitical and sociocultural threat dimensions remedy this shortcoming. We believe that for American identity to be measured as a social identity, it must account for social comparisons. It is not sufficient enough for people to categorize themselves and identify with a social group. The social group must be distinct in the minds of those who espouse an American identity. American identity should be considered in part a comparison to other social groups, not just a static description of what it means to be an American. As a result, our measure of American identity also considers social comparisons by incorporating into our analyses two additional dimensions: sociopolitical threat and sociocultural threat, which measure respondents’ tolerance for linguistic diversity and attitudes about Hispanic’s influence on America’s culture and workforce, respectively. These dimensions capture the effects of social comparisons because they presuppose differences between those in the in-group and those in the out-groups. We contend that notions of perceived threat serve as implicit comparisons, for they symbolize the favorability gap between the in-group and the out-groups. For one to view other individuals as potential threats indicates that the in-group member sees them as members of the out-groups. A threat is a negative perception, suggesting a detriment or an impediment. Therefore, to view someone as a threat is to view them negatively. As a result, individuals with an American identity will oppose immigration and support spending to combat illegal immigration because immigrants pose a threat, either sociopolitical or sociocultural or both.

3. The Relationship between American Identity and Immigration

Like so many other issues, immigration prompts individuals to think in group terms. More specifically, immigration encourages thinking along group terms. We call upon the social identity theory because we believe it sheds light on how Americans think about the issue of immigration. We hold that reliance on American identity is among the first thoughts one undertakes when encouraged to think about immigration, preceding notions of cultural and economic threat (

Breton 2015). Therefore, we propose a re-examination of American identity’s measurement and the new measure’s impact on public opinion towards immigration.

Among the first considerations people make when deciding whether he or she is for or against immigration is their membership in a social group relevant to the issue. Consistent with the social identity theory, we suspect that people place themselves in categories such as American or non-American. Social identity also leads Americans to think more positively of Americans or those with an American identity and less favorably of individuals who are not Americans or those without an American identity. Following self-categorization, social identification, and social comparison, people will take positions on immigration consistent with their in-group status. Conceptualizing the in-group as members of society who believe they embody an American identity, these in-group members will take a position on immigration that either helps the in-group or harms the out-group (those who are believed to lack an American identity). Disbelieving in the benefits of immigration for the in-group, those with an American identity will oppose immigration which harms those in the out-group and will support spending efforts to curtail illegal immigration at the border.

Shayo (

2009) provides the theoretical context of the social identity theory. He proffers that social identification is based on preferences for one social group and related desired outcomes over other social groups and related undesired outcomes. Preferences involve two features: the relative status of the numerous groups in society (resources such as income, education, etc.) and perceived likeness between the individual and other group members (appearance, attire, etc.). Social identity theory consists of more than just selecting a social group. It entails the prestige of the group in society. The higher the prestige of the group, the more likely people will self-select that group for membership.

The extent to which people become members of the group also involves whether they are similar to the other members of the group. Subsequently, in-group members will behave and think similarly and in ways to realize group goals and protect the group’s status (

Akerlof and Kranton 2000). Some people will strive to improve the lot of their group, even if that means making other groups less well off. People are more likely to join the effort especially if there is a high likelihood of achieving group goals (

Fowler and Kam 2007).

Based on these two features, people choose to identify with the group if the status of the group is relevant and they are identical to members of the group. That is, people are more likely to identify themselves with the group that is of higher status or that possesses more resources than other groups and people are more likely to identify themselves with the group that shares some critical characteristic. The status and similitude aspects of social identity are very apparent when it comes to the issue of immigration. The status difference between in-group and out-group is based on whether one believes s/he is an American or believe s/he has an American identity. In the context of immigration, Americans have a higher status than those who are seeking to become Americans. Also, by sharing important features that make up the American identity, individuals with an American identity have a higher status than immigrants because they believe immigrants lack an American identity.

The group’s status is vitally important here, for being an American or seeking to become an American is a highly-prized status. Such a status is very important to those who have it as well as to those who do not have it. When the in-group has what the out-group wants, then differences between the groups are heightened. Social identity theory suggests that in-group members bestow benefits on themselves and withhold benefits from the out-group. The in-group opposes efforts to equalize the groups. Thus, individuals with an American identity will oppose immigration and support efforts to eliminate illegal immigration. Individuals lacking an American identity will support immigration and oppose efforts to eliminate illegal immigration.

Undoubtedly, people must juggle multiple social identities.

Brewer (

2001) offers four strategies that people bring to bear to handle such situations. One option is to combine various social identifications that are similar. When social identifications are similar, they can overlap and have a combined effect. A second alternative is to develop an identification that simultaneously considers salient or relevant identifications. That is, multiple identities intersect to influence the individual’s political behavior. A third strategy is to designate different identities to be dominant based on the subject matter. For example, allowing a religious identity to predominate on matters of ethics or making a racial identity dominant on matters of culture. More pointedly, one would select their national identity to dominate on matters involving foreign countries or foreigners. A fourth strategy is to select one superordinate social identification, making all other social identifications subordinate to this dominant group identification. By adopting this stratagem, one gives prominence to the national identity and all other social identities are relevant inasmuch as they support the national identity.

We advance the fourth strategy discussed by

Brewer (

2001). We purport that an American social identity is a powerful force because it taps an identity that many in the United States share and, for some, supersedes all other social identities. That is, people may categorize and identify themselves based on several ways (race, gender, religion, geography, occupational, etc.), but a national identity will be shared by more individuals who also differ with respect to other social identities. Indeed, this is the case, for a predominant national identity supersedes subnational identities (

Gaertner and Dovidio 2000;

Transue 2007). It is the national identity that brings people together and, in this case, brings them together in unified opposition to members of groups who do not share the national identity. Hence, we hypothesize that American identity leads some to oppose immigration. It is not the country that garners such allegiance, but the identity or symbolism of what it means to be an American that galvanizes Americans and promotes coalescence against permitting people from other nations to enter the United States.

4. Data and Methods

Our investigation utilizes data from the 2004–2005 National Politics Study (

Jackson et al. 2004). Data for this survey was collected from September 2004 to February 2005. It has a total sample size of 3339, and a response rate of 30.6%. We use this survey rather than more recent data because this data set possesses the most comprehensive battery of questions that can serve as measures of the key concepts addressed in our analyses. Also, the survey includes questions that expand beyond the usual examination of opinions on legal immigration, providing the opportunity to estimate support for legal immigration and spending to halt illegal immigration.

We estimate two dependent variables, Immigration and Illegal Immigration. The Immigration variable gauges whether the respondent believes the number of immigrants entering the U.S. from foreign countries should be “increased” (coded 1), “left the same as it is now” (coded 0), or “decreased” (coded −1). The logic behind our coding strategy is that a negative value on a variable corresponds with the desire to lower the number of immigrants, while a positive value represents the opinion that the number immigrants should be higher. A value of 0, based on this logic, suggest that a respondent supports “no change” in the number (neither a decrease nor an increase). Likewise, the Illegal Immigration variable measures whether the respondent thinks that spending for “patrolling the border against illegal immigrants” should “increase” (coded 1), “stay the same” (coded 0), or “decrease” (coded −1). Because the response categories for these two dependent variables are ordinal—in the sense that they tap into respondents’ preferences regarding the preferred number of immigrants (legal or otherwise) that are permitted into the country—we employ ordered logit regression.

We wish to highlight the importance of both survey items before moving into the discussion on the operationalization of American identity. The variable Illegal Immigration is not the mirror reflection of Legal Immigration. One can support legal immigration but oppose spending on illegal immigration. Conversely, one can be opposed to legal immigration, but be supportive of spending to stem illegal immigration by patrolling the border. Illegal Immigration captures the desire to keep out individuals who are breaking the law or, for a more pernicious reason, because these immigrants are the “wrong” kind of people. In other words, they lack American identity or are less likely to obtain it. These two measures allow us to contribute not only to research about support for legal immigration, but also to our understanding of preferences to do more to combat illegal immigration.

American identity has never been measured the same way by different scholars, so as with them, we also use a plethora of relevant independent variables to construct our measure of American identity. A detailed description of all the dependent, independent, and control variables as well as question wording and coding strategies are presented in

Table 1. After identifying the relevant questions to serve as variables, we subjected the pertinent survey questions to a confirmatory factor analysis. The results reported in

Table 2 yielded five distinct dimensions. The five dimensions are labelled as: (1)

Born in the USA; (2)

Being Truly American; (3)

American Patriotism; (4)

Sociopolitical Threat; and (5)

Sociocultural Threat. We used the factor scores from these five dimensions to create the five independent variables that we ultimately use in our regression models as predictors of immigration attitudes.

1In addition to the theoretically-central predictors, each ordered logit regression model includes several control variables. These controls are used to help ensure the robustness of the American identity dimensions, for they help to isolate the effects of competing identities and other considerations. The control variables are Age, Gender, Education, Family Income, National Economics, Political Ideology, and Party Identification. Studies have found these variables to be influential, so they are placed in our models.

5. Analysis and Interpretation

To explore the relationship between American identity and immigration opinions, we specify ordered logistic regression models with the immigration items as our dependent variables, the variables containing our factor loadings from the five dimensions as the main predictors, and respondents’ demographic and political characteristics as control variables. It is clear from

Table 3 that all five of the factor dimensions comprising our measure of American identity are statistically significant. Holding other variables constant, a one-unit increase in the factor scores for the Born in the USA, Being Truly American, American Patriotism, and Sociopolitical Threat variables contributes to a decrease in the ordered log-odds of a respondent’s opinion about the preferred number of immigrants being permitted into the United States. A one-unit shift in the Sociocultural Threat variable, however, contributes to an increase in the ordered log-odds of this dependent variable. The pattern reverses for “illegal” rather than “legal” immigration: The ordered log-odds of a respondent’s preference for government spending on border protection increases across the first four dimensions of the American Identity construct and decreases across levels of the factor scores variable for the Sociocultural Threat dimension. These results lend credence to our hypotheses that those with an American identity will oppose legal immigration and support a strategy that keeps illegal immigrants out of the country.

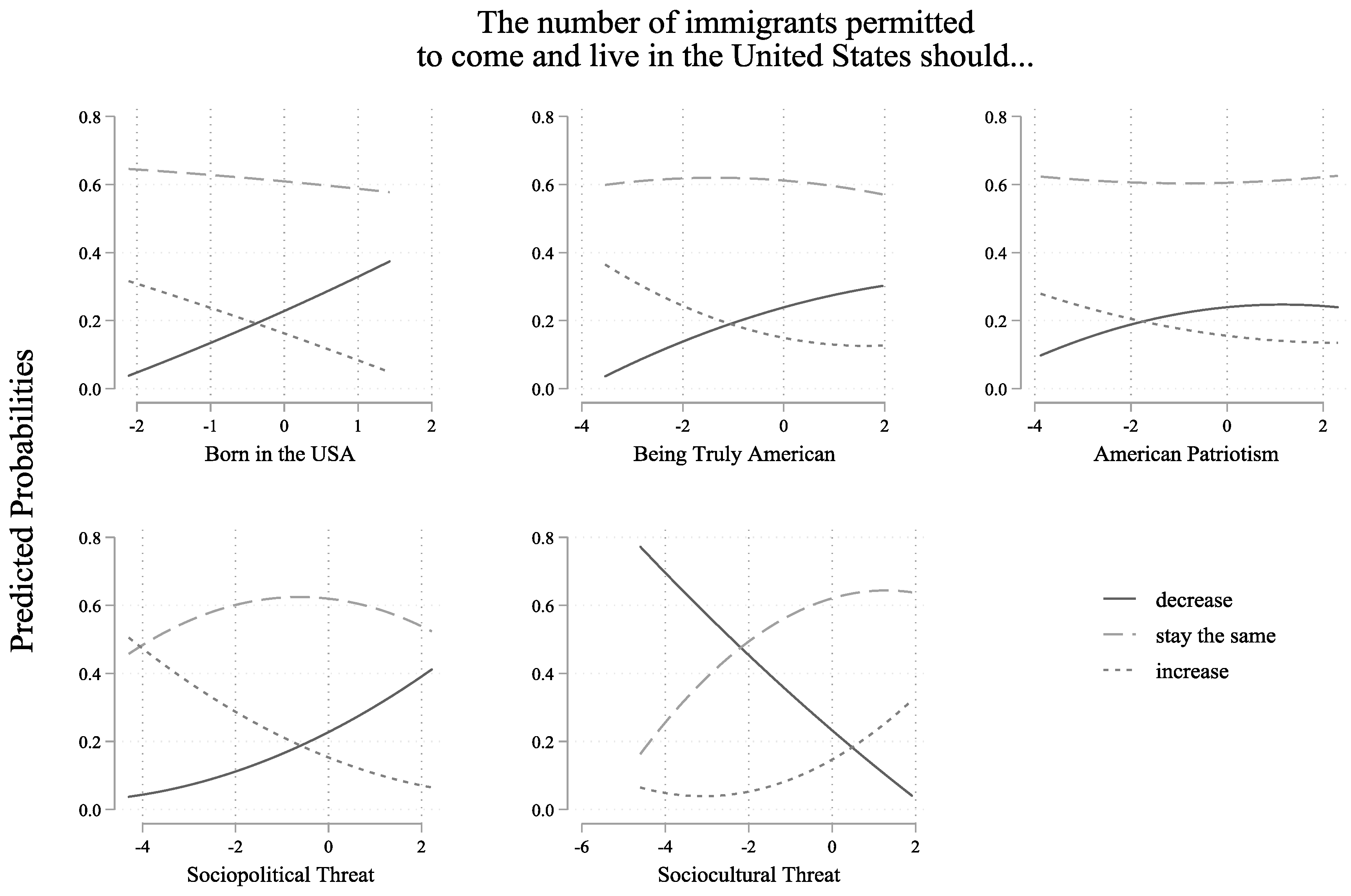

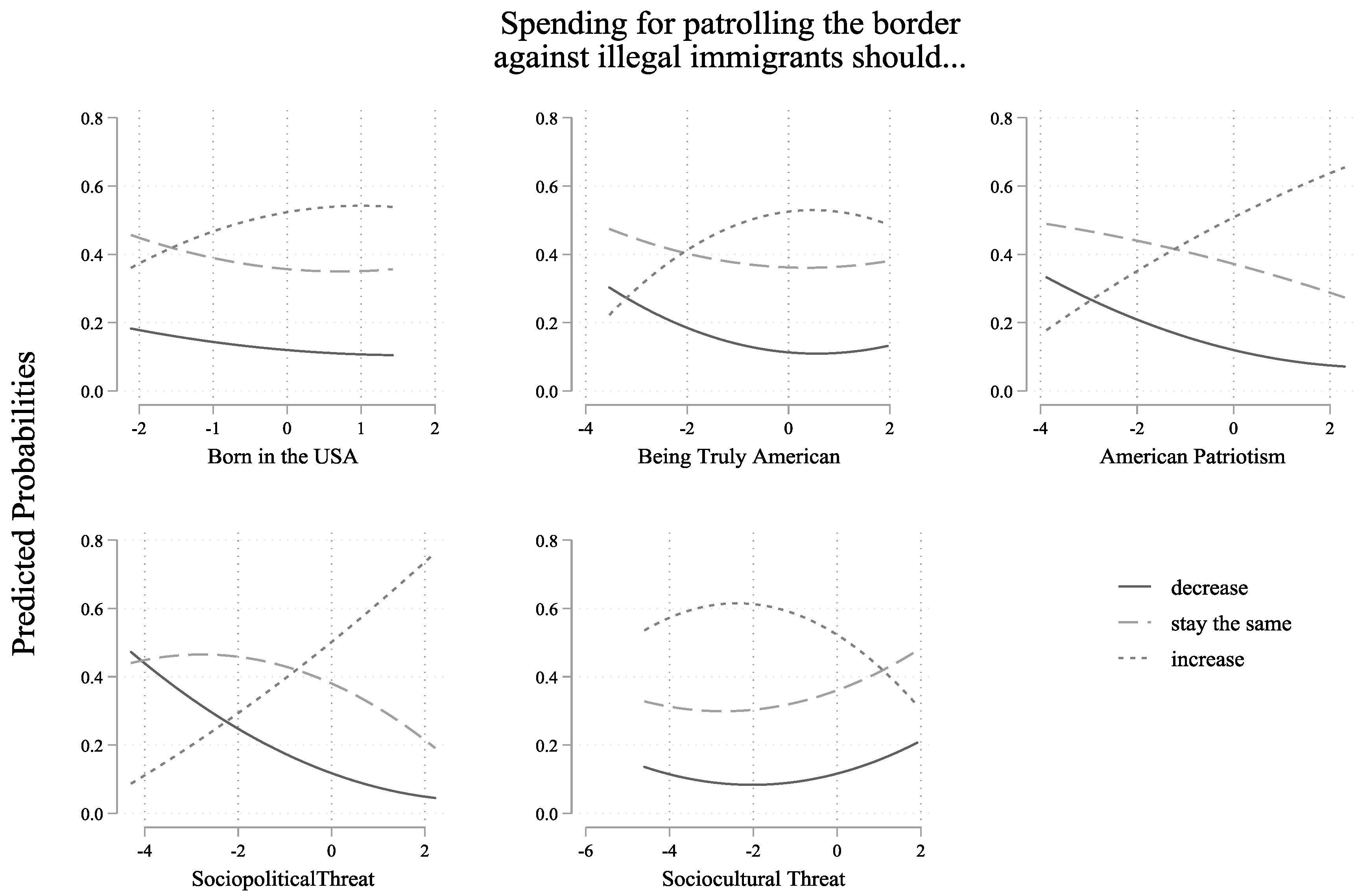

To illustrate the results, we estimate quantities of interest based on the ordered logistic regression models. Specifically, we display graphically how our dimensions of American identity influence preferences regarding the number of immigrants that should be allowed in the United States (

Figure 1) and attitudes about the amount of spending that should be devoted to border security (

Figure 2). The figures array the predicted probabilities of the response categories of our dependent variables (“increase” vs. “stay the same” vs. “decrease”) across the range of values in each of the five theoretically-central independent variables, holding the control variables constant. The Y-axis on each graph keeps track of the predicted probability levels and the X-axis records the values of that particular factor score variable. The lines within each graph provide a summary representation of the predicted probability of a respondent expressing a particular response. Readers should interpret each graph as if it contains a series of scatterplots. The dots for each response category of the dependent variable (sorted by the values of the factor score variables) are invisible, but the regression line summarizing the curvilinear relationship between these response categories and predictor variables are present.

It is clear from the post-estimation results that there is a negative association between the Born in the USA dimension and support for more legal immigrants coming into the country. For example, the predicted probability of a person saying that the number of immigrants permitted to come to America should increase starts low and then drops. Conversely, the predicted probability of a respondent saying that she believes the number of immigrants coming into the country should decrease starts low and rises considerably with increases in the values of this factor score variable. Finally, the predicted probability of respondents who think the numbers should “stay the same,” while initially higher than all other response categories, decreases slightly as we scan across the X-axis.

A similar pattern is also at work when it comes to opinions about anti-immigrant government spending. From

Figure 2, moving from the minimum to the maximum value of the Born in the USA variable, we observe that the willingness to spend money to keep illegal immigrants out of the country rises. Therefore, the predicted probability for the “increase spending” response category shifts upward while the predicted probability estimates for “decreasing spending” and “stay the same” categories drop.

We also discover evidence of a negative association between Being Truly American and support for legal immigration. As we go from the lowest to the highest values of this factor score variable, the predicted probabilities of respondents believing that the influx of immigrants should increase drops noticeably while the estimated probability of respondents who would prefer to see a decrease in the number of immigrants increases. Likewise, Being Truly American correlates positively with one’s support for anti-illegal immigrant spending. As expected, we observe a strong increase in the predicted probabilities of respondents believing that the government should devote more spending to patrol the border against illegal immigrants.

Similarly,

Figure 1 confirms that a negative relationship exists between American Patriotism and support for legal immigrants coming into the country (simultaneously, we report a relationship between American Patriotism and opposition to immigration). The predicted probability of a respondent who prefers that the number of immigrants permitted into the country decreases goes up (falls) with increases (decreases) in the values of this factor score variable. Consistent with previous findings, there is a positive association between American Patriotism and supporting spending efforts to keep illegal immigrants out of the country, and those patterns are clear from the downward (upward) slope of the regression lines summarizing the relationship between this factor score variable and the predicted probability of supporting decreases (increased) anti-immigrant spending.

In addition, there is a negative association between the Sociopolitical Threat factor score and support for legal immigration. The upward slope characterizes a relationship between the predicted probability of wanting the influx of immigrants to decrease and the factor scores characterizing that dimension and a downward slope summarizes a relationship between the factor dimension and the predicted probability and wanting immigration numbers to increase. Not surprisingly, believing that immigrants pose a sociopolitical threat correlates positively with supporting spending efforts to keep undocumented immigrants out of the country (as can be seen by the downward slope for decreasing anti-immigrant spending and the upward slope for increasing spending).

The findings for the Sociocultural Threat dimension are consistent with the findings above, though it breaks from the previous direction patterns. While the first four dimensions offer a negative relationship with support for legal immigration and a positive relationship with spending efforts to increase border security, this dimension of American identity presents the opposite. Specifically, we discover a positive association between the Sociocultural Threat dimension and support for legal immigrants coming into the country (

Figure 1) and a negative association between this threat dimension and supporting spending efforts to keep undocumented immigrants out of the country (

Figure 2). The common interpretation for all factor score variables is that individuals do not want those whom they perceive as lacking an American identity in this country.

6. Discussion

We follow the line of impressive scholars who have utilized social identity theory to explain the relationship between American identity and opinions toward immigration. However, we developed a measure of American identity that captures more fully the different aspects of social identity theory. We find that the traditional understanding of American identity should be broadened to include multiple dimensions, and we discuss the importance of five dimensions in particular. Consistent with the literature, our more thorough and comprehensive re-conceptualization of the American identity concept helps to predicts the degree to which people oppose legal immigration and support spending upsurges to contest illegal immigration at the border.

Our operationalization behaves as expected and is consistent with the extant literature. We did so by offering a more streamlined and yet more comprehensive treatment of the complex role of American identity on self-other distinctions, particularly as they pertain to conversations concerning not only the influx of immigrants into the United States, but also spending priorities to slow down illegal immigration.

Our analysis begins with the perspective that issues surrounding immigration are not just cultural or economic. We submit that the issues are more basic. That is, prior to specific beliefs or evaluations of immigrants or the economic and cultural impacts of immigration, people first consider whether the immigrant appears to be “good Americans.” The basis that people use to make the assessment of whether they themselves embody an American identity followed by an appraisal of whether the immigrants do as well. If the respondent has an American identity and believes that immigrants do not, then the respondent will oppose immigration and governmental budgetary priorities that urge more spending to attack illegal immigration at the border because immigrants are not a part of their group that embrace an American identity. This is because the respondent with an American identity is likely to perceive immigrants as members of the rival out-group and, consequently, incompatible with their American identity in-group. The result is a preference for reduced immigration as well as a pension to support government efforts to keep out of the U.S. people they believe also lack an American identity, namely, illegal immigrants.

The core of the current debate is how self-interest, national economic concerns, and group identities are related to public opinion on immigration. While controlling for self-interest and perceived national economic conditions and other known predictors of opinions on immigration, we find that American identity is a potent factor. Specifically, our model included measures of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, political orientation, economic concerns, as well as perceptions of American-ness, patriotism, social comparisons, and threat. Based on the results of the ordered logistic analyses, the five dimensions of America identity all relate to public opinion on immigration, both the legal and illegal variety, even when controlling for these other demographic and political characteristics.

One may have noticed that we do not explicitly discuss race. We do not for two reasons. First, race is embedded in the measures already. Because we implement a social identity strategy, our measures require respondents to compare themselves with others. They must compare their social group with other social groups. When respondents compare their social group to immigrants, race is a part of that calculus. More to the point, respondents are asked to compare their social group with Hispanics. Including a measure of social comparison with Hispanics was important to do because Hispanics are considered the face of immigration in the United States (

Brader et al. 2008). Second, this investigation is not alone in not discussing race explicitly. Most studies on American public opinion do not discuss race probably because America is very diverse and the types of immigrants coming to the United States is very diverse. Race is incorporated in our analysis, most likely embedded in the cultural concerns of the respondents.

We call upon future research to determine the applicability and generalizability of our research to other countries. That is, the social identity theory should be applied in multi-national analyses. While we are confident that future attempts to call upon social identity theory will be consistent with ours, it is not clear that it will. This is an empirical question and tests should be conducted. For instance, future research could compare our model of the United States with Canada.

There are reasons to believe that our investigation of the United States will yield the same results in Canada. The United States and Canada are known as countries of immigrants (

Citrin et al. 2012). Both the United States and Canada each year accept large numbers of immigrants (

Harell et al. 2012).

However, there are also reasons to believe that our investigation of the United States will not yield the same results in Canada. Attitudes toward immigration in the United States tend to be more hostile while attitudes in Canada are more favorable (

Harell et al. 2012). Our literature view of the United States is replete with studies that examine immigration as sources of cultural and economic threats. These same threats are present in Canada, but to a much lesser extent. Of course, the differences in perspectives on immigration between the United States and Canada are owed to Canada’s policy of multiculturalism which yields supportive attitudes toward immigration and immigrants (

Citrin et al. 2012). Other differences between the United States and Canada are the regions of the world where most of the immigrants originate. Canada accepts more immigrants from Asia, the Middle East, and China while the United States accepts more from Latin America and the Caribbean. Additionally, Canada and the United States have different immigration systems. This difference leads to differences in the socioeconomic status of the immigrants arriving in each country (

Harell et al. 2012).

For these reasons, we chose to examine only the United States and forego a comparison analysis with Canada. There are far more compelling reasons to examine the United States and Canada in separate analyses. To be sure, their starting points are different. The United States is more hostile to immigration and immigrants. Indeed, the hostility in the United States is more stark and visible in politics with Republicans making statements that many consider to be racist and bigoted. The hostility in the United States is more visible among the masses as evidenced by the many movements and demonstrations that oppose immigrants and immigration. The common view on immigration and immigrants holds Canada as a more open and welcoming society.