1. Introduction

Contestation over rights, livelihood security, and self-determination are key features in interactions between indigenous peoples, contemporary state actors and often-globalized non-governmental and commercial interests [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. While continuities and instructive parallels can be traced in encounters by indigenous peoples with colonial and imperial powers during the earlier twentieth century and beyond (e.g., [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]), the underlying dynamics of these struggles have evolved markedly since the later twentieth century with the ascendancy of the concept of “indigeneity”. Indigenous peoples have broadly embraced this concept and identity, using it to articulate their cultural distinctiveness and independence, justify claims to land and resources, forge wide-ranging alliances, and achieve a global visibility that is twinned with a moral forcefulness to demand attention and redress from policy makers and organs of national and international governance and law [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Yet indigeneity as a concept, and project, has not been without critique, being subject to limitations, risks and appropriations, and engendering disputes over definitional boundaries, inclusivity and its performance [

14,

16,

17].

According to Gregory Bateson ([

18], p. 241), a “double bind” occurs for an actor when “every move which he makes is the common-sense move in the situation as he correctly sees it at that moment, but his every move is subsequently demonstrated to have been wrong by the moves which other members of system make in response to his ‘right’ move.” These are situations “in which no matter what a person does, he can’t win” ([

18], p.201). This aptly describes the contradictions often faced by indigenous peoples and others when deploying the concept of indigeneity [

19,

20], a problematic that must be considered alongside its historical utility for advancing indigenous struggles, and its continued role as a foundation from which new concepts and strategies are evolving. Our study thus begins with a review of the broad challenges and potentials that the concept of indigeneity continues to present (

Section 2), particularly a foundational “double bind” in which the more modern or global indigeneity is seen as being, the more its authenticity as an identity is questioned.

We then offer three case studies that chart recent experiences and strategies adopted by indigenous peoples in responding to “no-win” situations that are superficially presented as, or at first sight appear to be, “win-win”. More specifically,

Section 3 examines the concept of “sumak kawsay” in how it emerged in Ecuador as an “alternative to development”, and how its political life has involved indigenous theorizations of Amazonian societies as “already developed”, on par with the West’s view of itself. Our second section details indigenous analyses and critiques of the limitations of the REDD+ initiative (the UN Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries) and emerging strategies to mobilize indigenous networks to combat these limitations and preempt expected double binds resulting from the programme’s implementation. Our third case details the utilization of external technical assistance among Bristol Bay (Alaska) native groups as part of what can be deemed (at least in the immediate term) a successful resistance strategy against minerals mining, in which we posit the potential for the emergence of a double bind in which the sophisticated technical definition and mapping of Bristol Bay natural resources in competition with state mapping risks an “arms race” and may breed dependence upon assistance from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in cycles of future mapping and counter-mapping.

2. The Double Bind of Indigeneity

Anthropology and the allied social sciences have always focused on the “local”. But in the course of the twentieth century, as globalization seemed to exert an increasingly hegemonic impact on localized human systems, there was a corresponding increase in academic interest in defining and defending the local, in particular indigenous identity, knowledge, and rights. This academic interest was paralleled and spurred on by an upsurge in indigenous advocacy worldwide [

21,

22,

23]. For example, the rubber tappers of the Amazon rose to global attention when they rearticulated themselves as indigenous people of the forest [

24]; and the little-known peasant land reform movement of the Zapatistas of Chiapas in Mexico rose to global prominence after it was reframed as a movement about Mayan indigeneity [

14,

25]. At the very time that the concept of indigeneity was being appropriated beyond the academy, however, it began to be critiqued within it. There have been several different bases for this critique: empirical, ontological, political, and hermeneutic.

The criticism on empirical grounds was stimulated by the ascendance of world system studies in the 1980s. Eric Wolf [

26] famously argued in 1982 that even isolated communities were caught up in global historical processes, which were even responsible for this very isolation. Exemplary of this shift in thinking are studies like that of Edwin Wilmsen [

27], who in 1989 argued that even iconic examples of isolated people like the San of the Kalahari Desert were integrated into modern capitalist economies both materially and discursively. Following this argument, indigenous peoples are not necessarily as isolated from other populations as once assumed.

Some scholars have taken this argument a step further to argue that globalization is actually responsible for indigeneity, which raises ontological questions. Two different arguments have been made in this regard. First, some scholars suggest that indigeneity is a product of confrontation with the non-indigenous modern world. For example, where clear tribal identities are found today in Indonesia, Tania Li ([

28], p. 158) argues that they can be traced to histories of confrontation and engagement, warfare and conflict. Second, others posit that the articulation of indigeneity is made possible by modern institutions. Frank Hirtz [

29] thus argues that recognition of a people as indigenous is embedded in the emergence of world society and its forms of communication and institutions. As a result, through the very process of being recognized as “indigenous”, these groups enter more firmly into the realm of modernity.

Questions of validity aside, some scholars have argued that indigenous status has not been as politically helpful to indigenous peoples as initially thought, that it contains perils as well as benefits. Li ([

28], p. 170) writes that the “indigenous slot” is a narrow target, which is easily over- or under-shot: if people present themselves as “too primitive”, they risk government intervention; whereas if they present themselves as “not primitive enough”, they risk intervention on other grounds (since the non-indigenous are seen as having no intrinsic rights to land). Similarly, Beth Conklin ([

30], p. 723) writes that “There is a fine line between the exotic and the alien–between differences that attract and differences that offend, unnerve, or threaten”. Once indigenous status has been attained, official expectations of appropriate behavior can also be exacting. However, the greatest harm of all may be incurred by those who cannot claim indigenous status.

As Li ([

28], p. 173) notes, “[the Indonesian] government could set out new rules to identify and accommodate a few ‘primitives’ or traditional/indigenous people, and even acknowledge their rights to special treatment, without fundamentally shifting its ground on the issue that affects tens of millions: recognition of their rights to the land and forest on which they depend.” For scholars such as Fernand de Varennes, however, “to lump the claims of indigenous peoples with those of minorities” is “a tendency that should be avoided” if indigenous autonomy and rights are to be advanced ([

31], p. 309). Yet the case of Ecuador (

Section 3) shows that meaningful successes can be achieved by indigenous peoples when focusing efforts beyond their own rights, in mobilizing broad popular support to effect change relevant to many social groups and causes.

Perhaps the most thought-provoking debates over indigeneity pertain to the involvement of indigenous peoples themselves in the articulation of indigenous identity. In sharp contrast to the increasingly cautious academic approach to indigeneity, the concept has traveled, been transformed, and enthusiastically deployed the world over [

32,

33]. Of concern to some is the notion that local communities have not just adapted the concept to their own uses but have done the reverse: adapted themselves to the concept. Jean Jackson [

34] writes about how local notions of history and culture in Vaupes, Columbia, have been changed to fit their perception of what outsiders define as “Indianness”; Laura Pulido [

35] writes of the deployment of romanticized ecological discourses and culturalism in the South-Western U.S. as a means of resistance using the “master’s tools”; and Li ([

36], p. 369) worries that an external “sedentarist metaphysics” is shaping the belief and practices of indigenous peoples in Indonesia.

Drawing on the Marxist sociologist and cultural theoretician Stuart Hall, Li [

28] lists variables that contribute to the success of articulations of indigeneity: resource competition, a local political structure, a local-state contest, a capacity to articulate identity to outsiders, and urban activist interest. She observes that simple portrayals of indigeneity connect with outsiders, whereas complex portrayals or “fuzzy” ones do not. Successful articulation also depends on the ability to connect to pre-existing discourses: the “audibility” of a story is greater if it fits a “familiar, pre-established pattern” ([

28], p. 157). The self-conscious articulation of indigenous identity has, however, often been interpreted as the “faking of indigeneity”. As Beth Conklin ([

30], p. 725) writes: “Theatricality is, to Western eyes, easily equated with acting, and the putting on and taking off of native garb can look like posing—the antithesis of authenticity”. She recounts vitriolic exposés in the Brazilian press, including juxtaposed photos of exotically costumed Kayapó activists and pictures of the same individuals offstage, dressed in Western clothes and engaged in “civilized” pursuits. Conklin ([

30], p. 724) further notes that:

To acknowledge that the body images of native activists are produced in relation to Western discourses and media dynamics is not to say that Amazonian Indians have sold out...All politics are conducted by adjusting one’s discourse to the language and goals of others, selectively deploying ideas and symbolic resources to create bases for alliance.

Focusing on the authenticity of performances of indigeneity is myopic given that, as Conklin implies, there is both an “audience” and wider role for such performances. Nor have indigenous scholars been silent on these topics. For example, Linda Tuhiwai Smith ([

37], pp. 72, 74) similarly critiques the double-binds regarding “who is a ‘real indigenous’ person, what counts as a ‘real indigenous leader’, [and] which person displays ‘real cultural values’”, since “at the heart of such a view of authenticity is a belief that indigenous cultures cannot change, cannot recreate themselves…nor can they be complicated, internally diverse or contradictory. Only the West has that privilege.” Tuhiwai Smith ([

37], p. 36) has also noted the danger of indigenous peoples and scholars themselves falling into the trap of writing or representing themselves “as if we really were ‘out there’, the ‘Other’, with all the baggage that this entails.” These sort of feedback dynamics are not unexpected: Anthony Giddens [

38] examined the “interpretive interplay” between social science and its subjects and concluded that theory cannot be kept separate from the activities composing its subject matter, a relationship he termed the “double hermeneutic”. The characterization of such behavior by self-conscious intent is troubling to some. Whereas a perceived lack of conscious intention in practices that conserve natural resources, for example, is widely deemed to prove the absence of indigenous “conservation”, with regard to articulation of indigenous identity, just the opposite is often believed to be true.

Academics have long been familiar with the idea of recurring paradigm changes in science [

39]. Concepts like indigeneity are subject to this same dynamic. Dissatisfaction with the fate of localized resource-use systems under totalizing systems of modernity stimulated interest in indigeneity and indigenous systems of resource knowledge and use over the past several decades. When the concept of indigenous knowledge was first recognized or promoted, it thus represented a useful counter to the customary denial that rational indigenous knowledge and practice could even exist. The concept of indigeneity was to prove very successful, giving rise to a whole new field of study, a novel thrust in “new social movements” literature (e.g., [

40]), and spurring an efflorescence of international legal recognition for indigenous rights to land, culture, and self-determination (by bodies such as the United Nations and the International Labor Organization). Yet as such rights were won, academics increasingly focused on difficulties with the concept, precisely at the same time as indigenous peoples themselves were increasingly employing the concept to great effect.

Our first case study examines the emergence and implications of “sumak kawsay”, a concept proposed by Ecuadorian indigenous social movements as an alternative to a concept of “development” that assumes that lack, or scarcity, is natural. Sumak kawsay, or “good living” (buen vivir), was nominally adopted by the Ecuadorian state in 2008, giving the term an influence on broader Ecuadorian culture and national planning. In 2009, Bolivia’s first indigenous government adopted a similar concept, and sumak kawsay has also attracted the attention of scholars and citizens worldwide.

3. Sumak Kawsay, Ecuador

We imagine that the management of natural resources will have to be under the legal authority of indigenous peoples and that this will be our contribution to development. From the point of view of management, our main pillar are the technologies of Pastaza indigenous peoples which we go on complementing with knowledges from other Amazonian indigenous peoples, other academics, and Western academics; incorporating certain tools, and methods of planning, systematization, and conservation, only to the extent that it contributes to our objectives…. We’re proposing an equilibrated “human-nature” management, looking toward using resources in the long run, because well, we don’t have any others.

––Leonardo Viteri, 23 March 2001 ([

41], p. 87)

Beginning with a major uprising in 1990, indigenous social movements led the transformation of Ecuadorian national politics for a remarkable fifteen years [

42]. This period saw the political disruption of nearly a dozen presidencies and, by the time a stable government was established under the leadership of Rafael Correa in 2006, a historically unique openness to addressing indigenous demands prevailed. In particular, during the drafting of a new constitution in 2008, the Constituent Assembly approved a framing of the constitution in terms of “sumak kawsay” (often translated as “good living” or “life in harmony”), a concept first proposed by Ecuadorian indigenous movements as an “alternative to development” [

41,

43,

44,

45,

46]. This section traces a brief history of this concept’s political life [

47].

Though it is composed from two common Quichua words—“sumak” (good, beautiful, delicious, perfect) and “kawsay” (life, existence)—sumak kawsay is a relatively new term [

48]. While “alli kawsay” (good life) had been used for decades if not centuries in Ecuador, and has deep moral resonances in Quichua culture, the term sumak kawsay only begins to appear in Ecuador by the late twentieth century in texts such as a Quichua-language Bible from the Chimborazo region of the Ecuadorian Andes, a region abutting the Amazonian province of Pastaza. In that Bible, “peace” and “shalom” are translated as “sumaj causai” [

49].

The 1970s saw the beginning of Ecuador’s oil boom. Along with missionization and land colonization, the oil boom was part of an intensification of capitalist extractivism in the Ecuadorian Amazon that brought tremendous social and environmental change. Indigenous resistance grew throughout the 1970s and 1980s [

50]. By the late-1980s there were well-organized Amazonian calls for “a new paradigm for economic development” ([

51], p. 153), particularly from neighboring Shuar, Achuar, Shiwiar, Waorani, and Quichua peoples in Ecuador’s Pastaza Province [

41]. Anthropology, often deployed by indigenous intellectuals and scholars themselves, played a key role in the representation of these Amazonian resistance processes. In 1976, the Federation of Shuar Centers co-published

An Original Solution for a Contemporary Problem [

52], which both critiqued and expanded upon anthropological concepts to fit regional struggles for land and self-determination. Based on fieldwork between 1976 and 1980, French anthropologist Philip Descola [

53] wrote about “shiir waras” as an Achuar concept referring to domestic peace and the maintenance of a hunting and swiddening system for living well. Descola described this Achuar concept as referring to the successful articulation of a system of living in the forest that “makes chronic failure more or less impossible…”, and gives “an almost automatic guarantee of success” ([

53], p. 428). Quichua (Runa) authors from Sarayaku published a number of texts about “sumak kawsay”, with one of the community’s most prolific authors being Carlos Eloy Viteri Gualinga [

44,

54,

55], who in 2003 received a degree in anthropology. All of the above texts came from, or were written about, Ecuador’s Pastaza Province, and all dealt in various ways with issues of social change in the face of rapid forest industrialization (see also [

56]).

Submitted for a master’s thesis in applied anthropology, Carlos Viteri’s ethnography, based on his upbringing in Sarayaku, described the workings of a Runa system for living “an ideal condition of existence without lack and crisis” ([

55], p. 47). Viteri emphasized that development is usually defined from the perspective of outside, colonial actors, who portray their own society as the pinnacle of civilization. The outsider is the one always considered to be already developed. Historically, they had also tended to see the Amazon as an empty, rather than a peopled, land. Such a paradigm placed Runa in the contradictory position of being categorized as “the least developed”, “the poorest of the poor”, when living most “traditionally” in the forest, for example, with “the existence of one’s own language, organization, arts, etc.” ([

55], p. 21). Responding to these assumptions, Carlos Viteri argued that there is no Sarayaku tradition of enacting advancement as a linear process, no conception of a “road of progress” in which one begins behind and gets ahead in a movement from underdevelopment to development. Similarly, he refused the notion that there is a Sarayaku Runa tradition of chronic poverty, noting that the closest Quichua concept,

mútsui, assumes that lack, such as might be caused by unforeseeable disasters or from not exercising foresight, is temporary and extraordinary ([

55], p. 72). “In contrast with súmak káusai,” he wrote that,

development is conceived of only in regard to lack and problems, and consequently it sets out a behind state of underdevelopment in order to appear like the “medicine” or formula for overcoming this behind state through a linear transit. Súmak káusai, on the other hand, functions as a social practice oriented precisely to avoiding a fall into aberrant conditions of existence.

In this formulation, there is no assumed lack of development. Instead, sumak kawsay is described as a system for

not de-developing. As Carlos Viteri’s cousin Franco Viteri remarked in an interview, “[T]he forest is already developed…What petroleum industries do is destroy what already

is developed” [

57]. As Carlos Viteri outlined it, moving towards this ideal of sumak kawsay necessarily implied neither departure from identity nor departure from place, but instead the maintenance and strengthening of both. Viteri’s account suggested a formal ontology in which fully developed forest life has “always already” ([

58], p. 199) existed. This different set of assumptions about the forest’s state of development probably owed to a Runa theory that the forest is constituted by the inter-relations among many kinds of living selves, which are themselves figured as people (Runa) [

58]. Seen in this way, the forest is like a city, full of people, rather than empty. This helps explain why Viteri [

44,

55] insisted that sumak kawsay shouldn’t be thought of as a species or kind of development (e.g., “indigenous development”) that would assume a natural state of emptiness and lack, but rather as a conceptual alternative in which there is assumed to be an already developed world potentially threatened by forces of de-development.

“While the elites embrace chimeras”, Viteri ([

55], p. ii) remarked, “the Amazonian nationalities maintain their own quotidian dynamics.” Leveling a critique from the dignified position of another “always already developed” society was tantamount to Runa claiming the same idea that the West has historically made about itself [

59]. Viteri’s work helped clarify and amplify sumak kawsay as part of an exit strategy from a conceptual impasse in which Runa people “couldn’t win”––developing while de-developing. Viteri’s early statement in a 1993 publication ([

54], p. 150) that “There is no good living without good land” [

no hay sumac causai sin sumac allpa] indicated that the sumak kawsay concept was closely tied to struggles for land and autonomy in Pastaza, a process that involved defining indigenous nationalities and territories that the state didn’t recognize, as well as conceptualizing how governance might work within and among them once established [

41].

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, sumak kawsay was taken up by key organizations in the national indigenous movement [

46]. As a result of their advocacy, the term came to be adopted by Rafael Correa’s winning political party in 2006, and in 2008 was made into a guiding concept of the nation’s new constitution. Carlos Viteri went to work heading the government’s Institute for the Eco-Development of the Amazonian Region (ECORAE), and he became a supporter of expanding the oil frontier. Meanwhile his home community of Sarayaku continued to resist oil operations. National sumak kawsay took on a more conventional shape, re-conceptualized from the state’s perspective. In the constitution, sumak kawsay lost its semantic connection to a concept of an already-developed life, and was instead figured as a national aspiration, as in the Preamble of the Constitution [

60]: “We women and men, the sovereign people of Ecuador….Hereby decide to build…A new form of public coexistence, in diversity and in harmony with nature, to achieve the good way of living, the sumak kawsay.” It became a term that any Ecuadorian could define more or less as one wished. With the government promoting some meanings over others, the term morphed into a key––and highly flexible––philosophical concept and slogan for the transformative ambitions of President Rafael Correa’s “Citizens’ Revolution.” In government documents such as the National Plan for Good Living, sumak kawsay is represented as a horizon to be reached at the end of a revolutionary process of ecological modernization (e.g., [

61]). “The Socialism of Sumak Kawsay”, according to a leading government intellectual, René Ramírez-Gallegos, is the endpoint of a three-phase process: from neoliberal capitalism, to socialism with markets, to the socialism of sumak kawsay [

62].

This governmental discourse thus rendered a statist reinterpretation of the term sumak kawsay along the lines of “Ecuadorian development”, focusing on what Ecuador might become in the future, rather than on the question of how certain kinds of advancement might or might not destroy what is already developed. Not unlike the Biblical translation of “sumaj causai”, national good living policy has emphasized an evolution and a providential peace to be reached. Situated within an imagined community (that of the nation-state), the term has tended to be used quite loosely and abstractly, and often without reference to the places it emerged from, like the forests of Pastaza, or the critical literatures of indigenous scholars such as Viteri. Most importantly, the Ecuadorian government’s continued claim to have ownership of all subsoil resources [

63], such as the crude oil under Sarayaku, has reasserted a familiar “can’t win” situation––where the sumak kawsay of the nation-state is based on loss of healthy forest, and the displacement of Pastaza indigenous peoples, for industries such as oil, timber, mining, and cash farming [

64].

In the above sense, the articulation of sumak kawsay and its subsequent re-articulation or part co-optation by other interests evokes the image of a classic double bind, but the story is not yet over. The wide circulation of this Quichua term has opened new channels and possibilities for communication. In some ways it represents a kind of globalizing of indigeneity, or a call for indigenizing the globe [

65]. Bolivia adopted a concept similar to sumak kawsay into its constitution one year after Ecuador, spurring international dialogues, and good living is now a mainstream, if often loosely used, reference concept in Ecuadorian public development planning and civil society discussions. Academic articles referencing sumak kawsay number over 1200 [

56]. It also has shared many of the features noted by Li [

28] of successful articulations of indigeneity: audibility within a pre-existing discourse, resource competition, local political structures, a local-state contest, a capacity to articulate identity to outsiders, and urban activist interest.

As Charles Hale ([

66], p. 184) notes of indigenous struggles in Central America, “Paradoxically, among the most daunting obstacles is [now] not repression or denial of rights, but, rather, partial recognition and the bureaucratic-political entanglements that follow”. While a conceptual hurdle was jumped, the problem of the state’s monopoly on violence and subsoil resources has been harder for Runa to challenge, and sumak kawsay has probably had as many ramifications outside as inside Ecuador. This also aptly prefaces our following case study, in which United Nations REDD and REDD+ programmes, announced as tools to mutually serve the interests of indigenous communities and meet conservation and climate change goals, have in practice been accompanied by and hold the potential for further considerable undesirable consequences for indigenous communities. The conception and objectives of these programmes arguably capitalized upon the growing acceptance of indigeneity as a legitimate identity and (in a further double bind) capitalized upon the success of indigenous peoples in articulating and justifying claims to land and resource rights and to support from international finance for conservation and development. Despite initial, cautious interest in the potential benefits of REDD+ for forest peoples, many indigenous leaders and organizations have become increasingly outspoken about the limitations and risks of the programme, thereby anticipating and pre-emptively confronting future double binds that may result from the programme’s implementation.

4. REDD Programme, Peru and Ecuador

As the international community has reached consensus about the anthropogenic origin of present global climate change, efforts to craft global responses and policy solutions to combat climate change have intensified. In December 2015, 195 nations attending the 21st Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change adopted the Paris Agreement, setting a long-term objective to hold the increase in global average temperatures “to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels” ([

67], p. 3, Article 2.1). This is to be facilitated by a (non-binding) collective commitment of a minimum of USD 100 billion in new climate finance per year starting in 2020 to support developing countries’ mitigation and adaptation. At least some of these funds will go to “policy approaches and positive incentives for activities relating to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation” ([

67], p. 6, Article 5.2), building upon and extending the existing UN Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD) [

68]. Proponents of REDD, as well as the updated REDD+ programme [

69], the remit of which has been expanded to include “conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks,” [

70] have often touted these policies as producing “win-win” scenarios. These are seen as having the potential to simultaneously reduce a major source of global emissions

1 and benefit forest protectors—those that reduce deforestation and degradation—perhaps especially indigenous peoples in the global South.

2 As example, the US-based Environmental Defense Fund has suggested that REDD+ “promotes development for indigenous communities by creating new sources of income to improve living standards while maintaining traditional ways of life” and that “indigenous peoples must not only play an active role in developing and implementing REDD+ programmes, but must also receive the majority of benefits from these initiatives” [

79].

The very existence of this programme and the international funding it entails speaks to the strength of developing countries positions about differentiated responsibilities, as well as the demands of international indigenous movements to justice and benefit-sharing from international conservation and development. Despite possible opportunities and benefits, many indigenous peoples and indigenous organizations have questioned and critiqued the programme, especially the threats to land security that might result from its implementation. In many forested areas, indigenous peoples continue to struggle for formal recognition and title to customary lands, and a dominant concern of many indigenous organizations, such as the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change, is that the monetary incentives from REDD might prompt powerful actors (including the state) to claim those lands or otherwise marginalize or negate indigenous land rights claims [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86].

This section draws on national indigenous federation statements as well as ethnographic fieldwork in Peru and Ecuador to examine the ways in which indigenous leaders and organizations are anticipating and critiquing potential double-binds that might result from REDD and REDD+.

3 In South America and elsewhere, indigenous leaders have cautiously assessed and in some cases pursued pilot programs to benefit from REDD+ (as well as related, or precursor, initiatives regarding “avoided deforestation” and payment for ecosystem services). For example, the indigenous Paiter Suruí of the Brazilian Amazon were the first such peoples to not only seek out but receive REDD+ credits, with the Chief remarking that “REDD+ is a bridge between the indigenous world and the non-indigenous world;” “it creates a vehicle through which the capitalist system can recognize the value of standing forests, and indigenous people can be rewarded for preserving them” [

87] (and see also [

88,

89]). Yet several years later, other Suruí leaders reportedly denounced the programme for creating divisionism and failing to produce promised benefits [

90]. Similarly, in Peru and Ecuador, a number of indigenous leaders were initially drawn to the potential financial benefits promised by REDD+, but have adopted a more critical stance after learning more about the initiative, perceiving a number of embedded threats.

In Ecuador, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon has strongly critiqued REDD and REDD+, and suggested that such policies will violate “our rights to lands, territories, and resources, steal our land, cause forced evictions, prevent access and threaten indigenous agricultural practices, destroy biodiversity and cultural diversity, and cause social conflicts” ([

91], p. 57). The Ecuadorian NGO

Acción Ecológica has also taken a highly critical stance toward REDD+, organizing gatherings and trainings for indigenous leaders and other interested parties about the dangers and immoralities of carbon markets. For example, in August 2011,

Acción Ecológica organized a workshop on “green capitalism” in the national capital of Quito. This focused on the ethical and moral dimensions of creating markets for biodiversity, water, and ecosystems services, particularly carbon markets and REDD. A central conclusion of the workshop was that it was “immoral and antithetical” to “commercialize life” and for northern polluters to clean their conscience and continue to emit by paying those in the south to curtail their own activities.

NGO positions, such as this one, both informed and were informed by positions taken by individual indigenous communities and organizations. Ecuadorian indigenous leaders from the community of Sarayaku have, for example, critiqued Ecuador’s pilot programme for REDD+,

Socio Bosque, as explained in August 2011 meetings between these leaders and indigenous leaders visiting from Peru to discuss REDD+ and ecosystem services payments, more broadly.

Socio Bosque was launched in 2008 to provide annual economic incentives (roughly $30 per hectare) directly to indigenous communities and other forest owners for protecting their forests [

92,

93]. According to the indigenous leaders from Sarayaku, communities that had participated in the initiative were outraged that limitations were placed on traditional activities like cutting wood and cutting palms and that permission was required to use their own resources. They also raised concerns that communities received money in an up-front lump sum but might be asked to return the full monies if they were deemed to have violated the seventeen clause contract, which could result either in indebtedness or loss of land. One leader also expressed discomfort at the issue of surveillance—that electronic monitors were placed in treetops to measure carbon emissions and that people in New York could use programs like Google Earth to monitor their investments in Quichua forests.

4The Peruvian national indigenous federation, AIDESEP (the Inter-Ethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest) also took a critical stance on REDD+, suggesting that REDD+, as it currently exists, “is a danger to [indigenous] peoples and to humanity” ([

94], p. 14) given that “contaminating companies…will continue contaminating” under its remit, while “the contracts will control the life of the community in relation to the forest…it will control the extraction of products, logging for subsistence [purposes], hunting, construction of new farms or homes, etc.” ([

94], pp. 13–14). To spread the word about these dangers, AIDESEP organized a series of workshops to analyze and critique REDD+. One such workshop was held outside the city of Iquitos in the region of Loreto in the northeast Peruvian Amazon; the April 2012 workshop was entitled “Territories, Forests, and Indigenous REDD+ in Loreto.” This workshop emphasized the potential dangers of REDD+ given the incomplete and inadequate land titling processes in Peru (especially the Peruvian Amazon) and the dangers associated with “carbon cowboys”, “pirates, scammers, and new contracts”—unscrupulous outsiders that entice indigenous communities to sign carbon-related contracts with the potential to undermine their land security or community interests in the long term (see, e.g., [

95,

96,

97,

98]). The workshop also reinforced their broader position in favor of what they called “Indigenous REDD+”, a platform that emphasized the need to complete indigenous land titling before the country goes forward with consideration of initiatives like REDD+. The promotion of initiatives like “Indigenous REDD+” suggests that, reservations aside, indigenous peoples are not totally closed off from considering REDD+ as a means to benefit their communities, but would like to see substantive changes in the programme, national legislation, and international climate finance to ensure that REDD+ respects or promotes rights, rather than violates them [

99,

100].

These exchanges, materials, and trainings resonated strongly with indigenous leaders like Alfonso Lopez Tejada, the president of the Cocama Association for Development and Conservation San Pablo de Tipishca (ACODECOSPAT). Throughout much of 2011, Alfonso Lopez would have been first to acknowledge that although he may have heard of REDD, he did not know enough about the associated policies to take a position on its merits. In July 2011, Lopez noted in an informal conversation that he had thought of REDD as a potential source of income, which community members’ desired to buy items like soap, medicine, shoes, or educational materials. However, given that many of the Cocama communities in the area are situated within the national park, Pacaya Samiria, which is legally state owned, Lopez questioned whether money from REDD would go to the communities or instead the state. Moreover, after discussing the promises and shortcomings of REDD with other indigenous leaders and advisors, Lopez came to understand that REDD+ projects and monies would likely be accompanied by other drawbacks and thus adopted a more critical stance, communicating to others in ACODECOSPAT that REDD+ was to be viewed with extreme caution. In an August 2011 meeting with the leadership board of the federation, Lopez emphasized that “the carbon market is a threat for indigenous peoples” given the strict contracts to “not kill another tree” and the tendencies toward closely monitoring their activities. He asked: “if we defecate in the forest would they know? Do we want to be controlled? The tree is not in the air—it is in the land…This is the empowerment of those that have money to the forests.”

In October 2011, Lopez presented a similarly critical stance at the annual congress of the federation, attended by representatives from 53 of the 57 communities comprising the federation. Here he suggested that if the communities accept money from REDD, then:

large transnationals will not worry about stopping [their own] contamination…but nonetheless want to obligate us to stop doing what we know how to do and to take our forests and our territories…the activities that we carry out in these forests will be controlled…From the other side of the world they can control [us] and know what we are doing…we cannot permit this.

Lopez went on to note that:

these concessions are for 40 years…this means if you sign a 40-year agreement now…that a child that is born now at 40 years old will not have access to this forest—will not have rights to access and use his resources as we know how to use them—in exchange for one-thousand soles [~USD $300]?!

5

Lopez’s personal transition from initial interest in REDD and REDD+ as a form of potential income or social support to taking a strong anti-REDD stance was significant in shaping the position of the broader federation, which represents 57 Cocama indigenous communities in the northeast Peruvian Amazon. Moreover, the evolution of Lopez’s thinking on REDD+ parallels the arcs in thinking and activism of a number of other indigenous leaders in the region.

The shifting indigenous positions on REDD+ demonstrate how an initiative designed with indigenous communities as one of the primary intended beneficiaries is being analyzed not only for its opportunities, but also the potential double-binds that may accompany financial incentives tied to forested lands and resources. Rather than accept the premise that REDD+ would bring money to communities, or even that development comes with money, indigenous debates and discussions yielded a plethora of practical, ethical, and structural concerns with the programme. Indigenous leaders have been particularly outspoken about the potential risks of losing land or curtailing resource use, including for local income or subsistence purposes, while simultaneously placing indigenous people under the gaze of northerners for extended contract durations. Indigenous critics have also denounced the programme for giving the primary “polluters” in the north a social license to continue to emit and to feel a degree of ownership over southern forests. This is doubly problematic in that it undermines the credibility of REDD+ in pursuing global emissions reductions while also giving a sense of superiority and control over indigenous peoples and other forest users.

In our final case study, drawing upon ongoing fieldwork and interviews in Bristol Bay, Alaska, we examine a diverse coalition of native and other interest groups opposed to a large scale mining development that threatens a renowned salmon fishery, both economically and culturally valued. In their opposition, this coalition has drawn on outside technical assistance from NGOs in the presentation of sophisticated counter-mapping to support their position, and here it is possible to posit an emergent double bind involving the risk of engendering a mapping “arms race” in competing directly with state actors and promoting dependence upon outside technical assistance from organizations whose own agendas and programmes may not always be fully congruent with the goals of the coalition. This is a salient observation given the above-discussed adversities associated with the multiple agendas of the REDD and REDD+ programmes, and the observations of scholars such as Brent Berlin and Elois Ann Berlin [

101] who illustrate how NGOs may sometimes arguably co-opt the voice of indigenous peoples.

5. Pebble Mine, Alaska

The proposal to mine the largest known undeveloped copper ore body in the world (commonly termed “the Pebble Mine” prospect) in a watershed also home to the largest sockeye salmon run in the world has engendered heated debate over future natural resource utilization in Bristol Bay, southwest Alaska. The Pebble Mine prospect is located on state-owned lands in the headwaters of Bristol Bay, which hosts both a major commercial fishery, and extensive subsistence fishing by residents of the rural region, most of whom identify as Alaska Native. The scale and scope of the proposed open-pit mine is such that, if built, it would be among the largest of its kind globally. This has galvanized opposition among an unlikely coalition of environmentalist, commercial and recreational fishing, and Alaska Native groups, with US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) involvement and boycotts by transnational jewelry companies, placing the issue prominently on the national and international stages, also attracting attention from prominent environmentalists such as Robert Redford. At the center of the debate is the question of how the territory and its resources should be managed, hinging upon how the territory is defined. Is it an area of rich, needed mineral deposits, or a vital watershed that is one of the world’s last “wild salmon strongholds” [

102]?

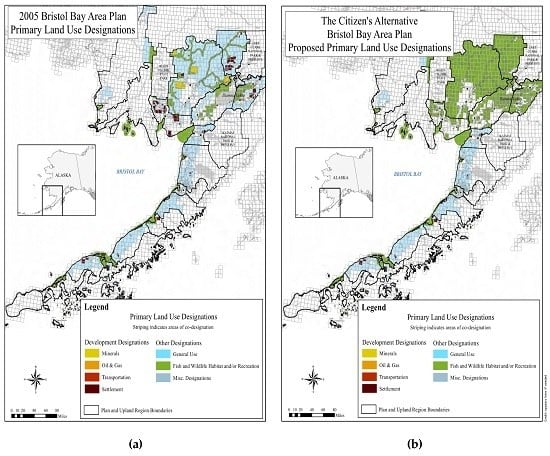

Key to this has been the mapping of territory carried out by the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR) in the 2005 “Bristol Bay Area Plan” (BBAP) and the counter-mapping by a collaborative group of non-governmental and native organizations. In the contest over legitimate environmental knowledge in Bristol Bay, mapping has thus emerged as a critical arena. The BBAP, serving as the master document in a regional planning system originating in 1984, employs maps to classify territory according to current uses and future best-use determinations. It concentrates on state-owned lands in Bristol Bay, including tidelands, encompassing a total 48 million acre area ([

103], pp. 1–3). Since their publication, these best-use land determinations have taken on new significance in the intensifying debate over mineral development in the region. Scrutiny by local residents revealed changes to the BBAP that had been quietly introduced into the 2005 version, differentiating it from the original 1984 document. The resulting controversy was such that in 2009 a group of plaintiffs including six Bristol Bay tribes, a commercial fishing organization, and the environmental organization Trout Unlimited, sued the DNR, which settled out of court in 2012 and agreed to revise the BBAP based on a public process [

104].

The primary point of contention was that the 2005 plan reclassified portions of land in Bristol Bay from reserved fish and wildlife habitat to other uses—and in the area of the Pebble claim, the land had been reclassified to mineral extraction as the primary use. In addition, the DNR was widely regarded as having allowed little to no input from important stakeholders, with the process of formulating the plan judged by local community members as decidedly less inclusive than the original 1984 plan. On being interviewed, a staff member from a region-wide Native organization outlined the differences seen in the 1984 and 2005 plans:

The 1984 plan was very much a locally-based plan. A lot of community involvement went into drafting that plan and it seemed like it was developed without much controversy…In 2005 when the DNR revised the plan…people were not very actively recruited to be involved...It was very much a DNR-administration-developed plan, not a people-, resource-, land-users-developed plan.

In 2005, a group comprising local tribes and national and international NGOs formulated “The Citizens’ Alternative Bristol Bay Area Plan for State Lands” (henceforth “Alternative Plan”) to address perceived flaws in the DNR plan [

105]. The architects of this Alternative Plan intended it to rectify both procedural and content criticisms leveled at the DNR’s plan. According to Trout Unlimited (one of the groups that co-funded the project), “the Citizens’ Alternative relies on science and better mapping to designate primary [land] uses and improve public participation” [

106]. The mapping for the Alternative Plan saw an increase in habitat and wildlife designated areas and placed subsistence as a primary land use category, restoring recognition of the relationships between people and land in planning documents that many believed were disrupted by the DNR’s 2005 maps. In effect, the Alternative Plan made visible that which the DNR had made invisible (see

Figure 1 for a spatial comparison). This was accomplished by a more participatory consultation process as well as extensive mapping of salmon-bearing streams, an inventory of resources in the area and their attached values.

By mapping a territory, it is made known, quantifiable and controllable in a way that reflects the interests, purposes and perceptions of the mappers [

107]. Historically, Angele Smith ([

8], p. 51) observes that “an interest in maps reflects a state of...uncertainty, turmoil, and contestation”, in which mapping, often in colonial contexts, has been “a tool of the state for legal appropriation of land, for military security...and for economic purposes such as taxation and resource exploitation.” Such a description remains apt in the era of digital mapping, and the Alternative Plan thus represents a notable instance in which the application of the “master’s tools” [

35] have been scrutinized by the subjects, and then applied effectively as a means of resistance against state actors more characteristically and historically endowed with the resources and claims to authority in mapping and defining the land.

Though these efforts have been clearly fruitful, several longer-term concerns emerge from this counter-mapping approach. Just as the DNR’s plans and tactics have had unintended and unplanned consequences, so may the plans and tactics of those who initiated this counter-mapping, including those characteristic of a double bind, that may act to bolster the very conduct the Alternative Plan was created to resist. By using the metrology introduced by the DNR in the counter-mapping, those who carried it out have in part acted to reify rather than question this approach to rendering the territory legible. The maps that the Citizen’s Alternative drafted, being based on the DNR’s methodologies, carried with them an abstracted, enumerating, and classifying view of the area. The problems of abstracted planning were not lost on Bristol Bay locals, with one interviewee noting:

what is wrong with government planning is that they deal in abstraction and the human face of those abstractions is lost. They compare the cost of fuel in Dillingham to the cost of fuel in Anchorage and they don’t see the old man walking just to get 2 gallons of stove oil—that old man’s face is just lost in planning, lost in statistics.

The creation of the Alternative Plan corresponded with increased NGO and charitable foundation activity in Bristol Bay due to the international attention attracted by the Pebble Mine prospect. The Alternative Plan was supported financially in large part by the Moore Foundation, which has an international programme focused on preserving salmon-bearing waterways. Producing a 200-page document and carrying out consultations in communities was a resource-intensive undertaking, necessitating significant financial support as well as the expertise associated with the technical aspects of the exercise. Even though these efforts seem to have met success in resisting the DNR’s plan, they raise questions about the ongoing ability of, for instance, southwest Alaskan subsistence fishermen to fund future counter-mapping initiatives that successful environmental claims-making has demanded in Bristol Bay. Further, while opposing the DNR’s planning attempts, the Citizen’s Alternative effort could ultimately serve to shore up DNR’s claim to be the legitimate state body for planning and permitting. Other strategies of, for example, setting up multi-stakeholder planning oversight on the DNR’s planning activities or even shifting the planning process to another state department have not been addressed. If the DNR’s authority in this arena is not questioned, an “arms race” of cycles of mapping and counter-mapping may become the norm, perhaps leaving those in rural regions like Bristol Bay beholden in a double bind to major funders to establish the frames for risk and value that motivate the calculation and classification of natural resources.

6. Conclusions

Far from fixating on how to best fit the “tribal slot” [

28] and its associated, expected behaviors, the indigenous actors reviewed in our case studies are taking greater ownership of strategies earlier used against them, chief among them outsiders’ perceptions of indigeneity. This has required the continual evolution of strategies and tactics to address challenges that initial successes springing from the adoption of indigeneity as an identity has not solved (and may have in some cases contributed to, in unanticipated double binds), not least the inadequacies, subversion and other adverse outcomes of policy, legal and constitutional provisions nominally intended to recognize and protect indigenous rights and cultures (e.g., [

108,

109,

110,

111,

112]).

For scholars of indigeneity, the imbrication of the indigenous in the theory of indigeneity has a number of implications. First, it problematizes the view of the global as post-local, post-indigenous. It argues for a theory, not of “indigeneity around the globe” but instead of “global indigeneity”, as the title of this special issue suggests. Second, it problematizes and destabilizes persistent assumptions about the divide between academic theory and academic subjects. Finally, to return to Bateson, it imposes a “double bind” upon scholars of indigenous peoples: if we critique the idea of the indigenous, this may in turn harm indigenous peoples in ways not wished for or even anticipated. One of the paths that Bateson offered out of the double bind is meta-communication, or communication about communication–which in this context would consist of those who deploy the term indigenous, explicitly discussing how and why the concept is and is not deployed.

The need for such meta-communication is urgent, not least concerning the contribution it may make to the welfare of urbanized or peri-urban indigenous peoples and communities who have particularly struggled to gain recognition from policy makers and state actors for whom the concept of indigeneity still cleaves (whether from inertia or convenience) to a traditional image of rurality. As Hannah Moeller ([

111], p. 201) states in relation to the UN 2007 Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples, “postulating the ‘indigenous’ evokes preservationist tactics, meriting value through classification and boundaries” in which “Textual and spatial definitions assert control…that may inhibit, not enrich, the conservation of indigenous cultural heritage”. Of the Bolivian legislation introduced in response to the Declaration, she further notes its “distinctly rural spatial demarcations…” that “...avoids predominant indigenous populations living on the periphery of urban centers as a result of post-colonial migration” ([

111], p. 201). Ryan Walker and Manuhuia Barcham ([

113], p. 314) similarly note that struggles for autonomy and rights among urbanized indigenous peoples in Canada, New Zealand and Australia are impeded because “The place of authentic indigeneity in the public perception has remained outside of urban areas”. That poverty among people who “qualify” as indigenous is often perceived as being different in character, more worthy or obligatory of remedial action, than poverty among other groups, such as indigenous people in urban contexts [

114], signals both the continuing potency and problematics of the concept in its utility in indigenous struggles.

In these struggles, it is clear that indigenous peoples can if they choose continue to build upon the gains and opportunities brought by the popular, moral, legal and policy recognition of “indigeneity”, but meta-communication is again merited to address new impediments to efforts by indigenous peoples to ensure they remain (in both their own and others’ perceptions) actors rather than subjects or victims. Illustrative here is Bethany Haalboom and David Natcher’s ([

115], p. 319) examination of the increasing labelling of Arctic indigenous communities by scholars as “vulnerable” to climate change, a label that comes with adverse connotations, and “has the potential to shape how northern indigenous peoples come to see themselves as they construct their own identities [and]...ultimately hinder their efforts to gain greater autonomy over their own affairs”. The self-conscious positioning of many indigenous peoples as overt actors, in which indigeneity-as-identity is not necessarily abandoned but reworked (as by indigenous scholars who argue against conceptions of indigenous cultures as unchanging and static [

17]), appears crucial. It allows strategies of resistance to evolve and escape from double binds, as in our case studies, as well as other cases wherein indigenous peoples are now vying directly with state and transnational actors in the production, interpretation and representation of information and knowledge, and challenging through the courts the inadequacies of legal and constitutional changes enacted with rigid, skewed, partial or subverted understandings of indigeneity as an identity and of indigenous concepts such as sumak kawsay.