High Throughput Sequencing to Detect Differences in Methanotrophic Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae in Surface Peat, Forest Soil, and Sphagnum Moss in Cranesville Swamp Preserve, West Virginia, USA

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

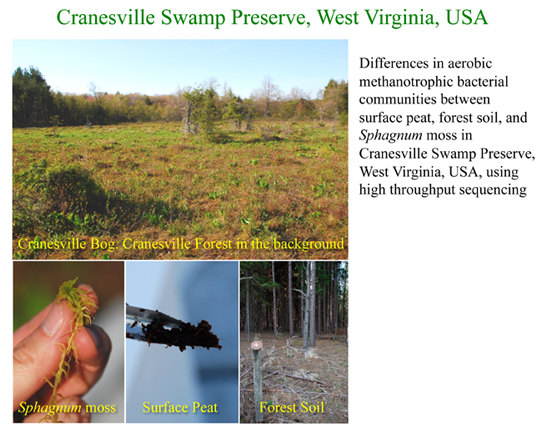

2.1. Site Description, pH Measurement and Collections

2.2. DNA Extraction and Purification

2.3. Illumina Library Generation

2.4. Bioinformatic Analyses

2.5. Phylogenetic Analyses

2.6. Statistical and Ecological Analyses

2.7. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

3. Results

3.1. pH Measurement

3.2. Bacterial Taxon Richness and Diversity

3.3. Phylogeny of 16S rRNA Sequences Related to Methanotrophs

3.4. Statistical and Ecological Analysis of Putative Methanotroph 16S rRNA Gene Sequences

3.5. Shannon-Weiner Diversity Index (H) and Species Evenness (E)

3.6. NMDS Analysis of 16S rRNA Sequences Related to the Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dlugokencky, E.J.; Nisbet, E.G.; Fisher, R.; Lowry, D. Global atmospheric methane: Budget, changes and dangers. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2011, 369, 2058–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, R.S.; Hanson, T.E. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 60, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Megonigal, J.P.; Guenther, A.B. Methane emissions from upland forest soils and vegetation. Tree Physiol. 2008, 28, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschke, S.; Bousquet, P.; Ciais, P.; Saunois, M.; Canadell, J.G.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Bergamaschi, P.; Bergmann, D.; Blake, D.R.; Bruhwiler, L.; et al. Three decades of global methane sources and sinks. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, J.K.; Keenan, T.F.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Richardson, A.D. Forest ecosystem changes from annual methane source to sink depending on late summer water balance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeburgh, W.S. Oceanic methane biogeochemistry. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 486–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, R.D.; White, J.R.; Lawson, J.E.; Gilmour, B.S. Methane efflux from emergent vegetation in peatlands. J. Ecol. 1996, 84, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Mer, J.; Roger, P. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: A review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2001, 37, 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Liebner, S.; Wagner, D. Abundance, distribution and potential activity of methane oxidizing bacteria in permafrost soils from the Lena Delta, Siberia. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Dumont, M.G.; McNamara, N.P.; Chamberlain, P.M.; Bodrossy, L.; Stralis-Pavese, N.; Murrell, J.C. Diversity of the active methanotrophic community in acidic peatlands as assessed by mRNA and SIP-PLFA analyses. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Dumont, M.G.; Neufeld, J.D.; Bodrossy, L.; Stralis-Pavese, N.; McNamara, N.P.; Ostle, N.; Briones, M.J.; Murrell, J.C. Revealing the uncultivated majority: Combining DNA stable-isotope probing, multiple displacement amplification and metagenomic analyses of uncultivated Methylocystis in acidic peatlands. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 2609–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knittel, K.; Boetius, A. The anaerobic oxidation of methane—Progress with an unknown process. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 63, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuur, E.A.G.; Vogel, J.G.; Crummer, K.G.; Lee, H.; Sickman, J.O.; Osterkamp, T.E. The effect of permafrost thaw on old carbon release and net carbon exchange from tundra. Nature 2009, 459, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgham, S.D.; Cadillo-Quiroz, H.; Keller, J.K.; Zhuang, Q. Methane emissions from wetlands: biogeochemical, microbial, and modeling perspectives from local to global scales. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2013, 19, 1325–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, J.; Ronholm, J.; Mykytczuk, N.C.S.; Greer, C.W.; Onstott, T.C.; Whyte, L.G. Methanogen community composition and rates of methane consumption in Canadian High Arctic permafrost soils. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2009, 6, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghoebarsing, A.A.; Smolders, A.J.; Schmid, M.C.; Rijpstra, W.I.C.; Wolters-Arts, M.; Derksen, J.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Schouten, S.; Damste, J.S.S.; Lamers, L.P.M.; et al. Methanotrophic symbionts provide carbon for photosynthesis in peat bogs. Nature 2005, 436, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, E.; Ahmad, A.; Steudler, P.A.; Cavanaugh, C.M. Molecular characterization of methanotrophic communities in forest soils that consume atmospheric methane. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 60, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, I.R.; Bodrossy, L.; Chen, Y.; Murrell, J.C. Molecular ecology techniques for the study of aerobic methanotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, S. The quest for atmospheric methane oxidizers in forest soils. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2009, 1, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kip, N.; van Winden, J.F.; Pan, Y.; Bodrossy, L.; Reichart, G.-J.; Smolders, A.J.P.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Damsté, J.S.S. Global prevalence of methane oxidation by symbiotic bacteria in peat-moss ecosystems. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kip, N.; Dutilh, B.E.; Pan, Y.; Bodrossy, L.; Neveling, K.; Kwint, M.P.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Op den Camp, H.J.M. Ultra-deep pyrosequencing of pmoA amplicons confirms the prevalence of Methylomonas and Methylocystis in Sphagnum mosses from a Dutch peat bog. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2011, 3, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kip, N.; Ouyang, W.; van Winden, J.; Raghoebarsing, A.; van Niftrik, L.; Pol, A.; Pan, Y.; Bodrossy, L.; van Donselaar, E.G.; Reichart, G.J.; et al. Detection, isolation, and characterization of acidophilic methanotrophs from Sphagnum mosses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 5643–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, E.; Fisher, M.C.; Steudler, P.A.; Cavanaugh, C.M. The methanol dehydrogenase gene, mxaF, as a functional and phylogenetic marker for proteobacterial methanotrophs in natural environments. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serkebaeva, Y.M.; Kim, Y.; Liesack, W.; Dedysh, S.N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of the bacteria diversity in surface and subsurface peat layers of a northern wetland, with focus on poorly studied phyla and candidate divisions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siljanen, H.M.; Saari, A.; Krause, S.; Lensu, A.; Abell, G.C.; Bodrossy, L.; Bodelier, P.L.; Martikainen, P.J. Hydrology is reflected in the functioning and community composition of methanotrophs in the littoral wetland of a boreal lake. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 75, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degelmann, D.M.; Borken, W.; Kolb, S. Methane oxidation kinetics differ in European beech and Norway spruce soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 60, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op den Camp, H.J.M.; Islam, T.; Stott, M.B.; Harhangi, H.R.; Hynes, A.; Schouten, S.; Jetten, M.S.M.; Birkeland, N.-K.; Pol, A.; Dunfield, P.F. Environmental, genomic and taxonomic perspectives on methanotrophic Verrucomicrobia. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2009, 1, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, H.; Abe, M.; Miyazaki, M.; Nunoura, T.; Furushima, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Takai, K. Methylomarinovum caldicuralii gen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately thermophilic methanotroph isolated from a shallow submarine hydrothermal system, and proposal of the family Methylothermaceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedysh, S.N. Cultivating uncultured bacteria from northern wetlands: knowledge gained and remaining gaps. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorobev, A.V.; Baani, M.; Doronina, N.V.; Brady, A.L.; Liesack, W.; Dunfield, P.F.; Dedysh, S.N. Methyloferula stellata gen. nov., sp. nov., an acidophilic, obligately methanotrophic bacterium that possesses only a soluble methane monooxygenase. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 2456–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, S.; Makarova, K.S.; Saw, J.H.W.; Senin, P.; Ly, B.V.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Galperin, M.Y.; Omelchenko, M.V.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the extremely acidophilic methanotroph isolate V4, Methylacidiphilum infernorum, a representative of the bacterial phylum Verrucomicrobia. Biol. Direct 2008, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Crombie, A.; Rahman, M.T.; Dedysh, S.N.; Liesack, W.; Stott, M.B.; Alam, M.; Theisen, A.R.; Murrell, J.C.; Dunfield, P.F. Complete genome sequence of the aerobic facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris BL2. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 3840–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartram, A.K.; Lynch, M.D.J.; Stearns, J.C.; Moreno-Hagelsieb, G.; Neufeld, J.D. Generation of multimillion-sequence 16S rRNA gene libraries from complex microbial communities by assembling paired-end Illumina reads. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3846–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1621–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravindrajam, C.; Viszwapriya, D.; Pandian, K.S. Ultradeep 16S rRNA sequencing analysis of geographically similar but diverse unexplored marine samples reveal varied bacterial community composition. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lentini, V.; Gugliandolo, C.; Bunk, B.; Overmann, J.; Maugeri, T.L. Diversity of prokaryotic community at a shallow marine hydrothermal site elucidated by Illumina sequencing technology. Curr. Microbiol. 2014, 69, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckert, K.A.; Kunkel, T.A. DNA polymerase fidelity and the polymerase chain reaction. Genome Res. 1991, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembel, S.W.; Wu, M.; Eisen, J.A.; Green, J.L. Incorporating 16S Gene Copy Number Information Improves Estimates of Microbial Diversity and Abundance. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.J.; Raskin, L. PCR biases distort bacterial and archaeal community structure in pyrosequencing datasets. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patin, N.V.; Kunin, V.; Lidström, U.; Ashby, M.N. Effects of OTU clustering and PCR artifacts on microbial diversity estimates. Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 65, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.; Hall, M.W.; Lynch, M.D.; Moreno-Hagelsieb, G.; Neufeld, J.D. Evaluating bias of Illumina-based bacterial 16S rRNA gene profiles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 5717–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüke, C.; Krause, S.; Cavigiolo, S.; Greppi, D.; Lupotto, E.; Frenzel, P. Biogeography of wetland rice methanotrophs. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Nature Conservancy. Available online: http://www.nature.org (assessed on 15 January 2015).

- Venable, N.J. Cranesville Swamp. Morgantown: West Virginia University; West Virginia University Extension Service: Morgantown, WV, USA, 1991; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer, G.; de Waal, E.C.; Uitterlinden, A.G. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- West Virginia University Genomics Core Facility. Available online: http://www.as.wvu.edu:8080/lampp/genomics/gcore (assessed on 15 January 2015).

- Illumina® MiSeq Desktop Sequencer. Available online: http://www.illumina.com/systems/miseq.ilmn (assessed on 15 January 2015).

- Illumina® BaseSpace® Genomics Cloud computing. Available online: https://basespace.illumina.com/home/index (assessed on 15 January 2015).

- Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME). Available online: http://qiime.org (assessed on 15 January 2015).

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.D.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masella, A.P.; Bartram, A.K.; Truszkowski, J.M.; Brown, D.G.; Neufeld, J.D. PANDAseq: Paired-end assembler for Illumina sequences. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.D.J.; Masella, A.P.; Hall, M.W.; Bartram, A.K.; Neufeld, J.D. AXIOME: Automated exploration of microbial diversity. GigaScience 2013, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.R.; Wang, Q.; Cardenas, E.; Fish, J.; Chai, B.; Farris, R.J.; Kulam-Syed-Mohideen, A.S.; McGarrell, D.M.; Marsh, T.; Garrity, G.M.; et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: Improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D141–D145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.R.; Chai, B.; Farris, R.J.; Wang, Q.; Kulam-Syed-Mohideen, A.S.; McGarrell, D.M.; Bandela, A.M.; Cardenas, E.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M. The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): Introducing myRDP space and quality controlled public data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D169–D172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, D.A.; Cavanaugh, M.; Clark, K.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Lipman, D.J.; Ostell, J.; Sayers, E.W. Genbank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D36–D42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegan: Community Ecology Package. Available online: http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (assessed on 15 January 2015).

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Python Version 2.7. Available online: https://www.python.org/download/releases/2.7 (assessed on 15 January 2015).

- Hoefman, S.; van der Ha, D.; de Vos, P.; Boon, N.; Heylen, K. Miniaturized extinction culturing is the preferred strategy for rapid isolation of fast-growing methane-oxidizing bacteria. Microb Biotechnol. 2012, 5, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Danilova, O.V.; Kulichevskaya, I.S.; Rozova, O.N.; Detkova, E.N.; Bodelier, P.L.; Trotsenko, Y.A.; Dedysh, S.N. Methylomonas paludis sp. nov., the first acid-tolerant member of the genus Methylomonas, from an acidic wetland. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2282–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, H.; Fuse, H.; Abe, M.; Miyazaki, M.; Nakamura, T.; Nunoura, T.; Furushima, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Takai, K. Methylomarinum vadi gen. nov., sp. nov., a methanotroph isolated from two distinct marine environments. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 3, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedysh, S.N.; Belova, S.E.; Bodelier, P.L.E.; Smirnova, K.V.; Khmelenina, V.N.; Chidthaisong, A.; Trotsenko, Y.A.; Liesack, W.; Dunfield, P.F. Methylocystis heyeri sp. nov., a novel type II methanotrophic bacterium possessing “signature” fatty acids of type I methanotrophs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dianou, D.; Ueno, C.; Ogiso, T.; Kimura, M.; Asakawa, S. Diversity of cultivable methane-oxidizing bacteria in microsites of a paddy field: Investigation by cultivation method and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Microbes Environ. 2012, 27, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, J.; Lee, S.W.; Yoon, S.; Dispirito, A.A.; Semrau, J.D. Characterization of a novel facultative Methylocystis species capable of growth on methane, acetate and ethanol. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2011, 3, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dam, B.; Dam, S.; Kube, M.; Reinhardt, R.; Liesack, W. Complete genome sequence of Methylocystis sp. strain SC2, an aerobic methanotroph with high-affinity methane oxidation potential. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6008–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedysh, S.N.; Khmelenina, V.N.; Suzina, N.E.; Trotsenko, Y.A.; Semrau, J.D.; Liesack, W.; Tiedje, J.M. Methylocapsa acidiphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel methane-oxidizing and dinitrogen-fixing acidophilic bacterium from Sphagnum bog. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dedysh, S.N.; Berestovskaya, Y.Y.; Vasylieva, L.V.; Belova, S.E.; Khmelenina, V.N.; Suzina, N.E.; Trotsenko, Y.A.; Liesack, W.; Zavarzin, G.A. Methylocella tundrae sp. nov., a novel methanotrophic bacterium from acidic tundra peatlands. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunfield, P.F.; Khmelenina, V.N.; Suzina, N.E.; Trotsenko, Y.A.; Dedysh, S.N. Methylocella silvestris sp. nov., a novel methanotroph isolated from an acidic forest cambisol. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunfield, P.F.; Belova, S.E.; Vorobev, A.V.; Cornish, S.L.; Dedysh, S.N. Methylocapsa aurea sp. nov., a facultative methanotroph possessing a particulate methane monooxygenase, and emended description of the genus Methylocapsa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 2659–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettwig, K.F.; van Alen, T.; van de Pas-Schoonen, K.T.; Jetten, M.S.; Strous, M. Enrichment and molecular detection of denitrifying methanotrophic bacteria of the NC10 phylum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 3656–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramette, A. Multivariate analyses in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 62, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilova, O.V.; Dedysh, S.N. Abundance and diversity of methanotrophic Gammaproteobacteria in northern wetlands. Microbiology 2014, 83, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedysh, S.N.; Dunfield, P.F.; Derakshani, M.; Stubner, S.; Heyer, J.; Liesack, W. Differential detection of type II methanotrophic bacteria in acidic peatlands using newly developed 16S rRNA-targeted fluorescent oligonucleotide probes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2003, 43, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedysh, S.N. Exploring methanotroph diversity in acidic northern wetlands: Molecular and cultivation-based studies. Microbiology 2009, 78, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragina, A.; Berg, C.; Müller, H.; Moser, D.; Berg, G. Insights into functional bacterial diversity and its effects on Alpine bog ecosystem functioning. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, N.; Larsen, Ø.; Sakwa, J.; Bruseth, L.; Khouri, H.; Durkin, A.S.; Dimitrov, G.; Jiang, L.; Scanlan, D.; Kang, K.H.; et al. Genomic insights into methanotrophy: the complete genome sequence of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, e303. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobev, A.; Jagadevan, S.; Jain, S.; Anantharaman, K.; Dick, G.J.; Vuilleumier, S.; Semrau, J.D. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of the facultative methanotroph Methylocystis sp. strain SB2 grown on methane or ethanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3044–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lau, E.; IV, E.J.N.; Dillard, Z.W.; Dague, R.D.; Semple, A.L.; Wentzell, W.L. High Throughput Sequencing to Detect Differences in Methanotrophic Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae in Surface Peat, Forest Soil, and Sphagnum Moss in Cranesville Swamp Preserve, West Virginia, USA. Microorganisms 2015, 3, 113-136. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms3020113

Lau E, IV EJN, Dillard ZW, Dague RD, Semple AL, Wentzell WL. High Throughput Sequencing to Detect Differences in Methanotrophic Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae in Surface Peat, Forest Soil, and Sphagnum Moss in Cranesville Swamp Preserve, West Virginia, USA. Microorganisms. 2015; 3(2):113-136. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms3020113

Chicago/Turabian StyleLau, Evan, Edward J. Nolan IV, Zachary W. Dillard, Ryan D. Dague, Amanda L. Semple, and Wendi L. Wentzell. 2015. "High Throughput Sequencing to Detect Differences in Methanotrophic Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae in Surface Peat, Forest Soil, and Sphagnum Moss in Cranesville Swamp Preserve, West Virginia, USA" Microorganisms 3, no. 2: 113-136. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms3020113

APA StyleLau, E., IV, E. J. N., Dillard, Z. W., Dague, R. D., Semple, A. L., & Wentzell, W. L. (2015). High Throughput Sequencing to Detect Differences in Methanotrophic Methylococcaceae and Methylocystaceae in Surface Peat, Forest Soil, and Sphagnum Moss in Cranesville Swamp Preserve, West Virginia, USA. Microorganisms, 3(2), 113-136. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms3020113