Bacterial Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Much More Than Antibiotic Resistance Determinants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Multidrug Efflux Pumps and Antibiotic Resistance

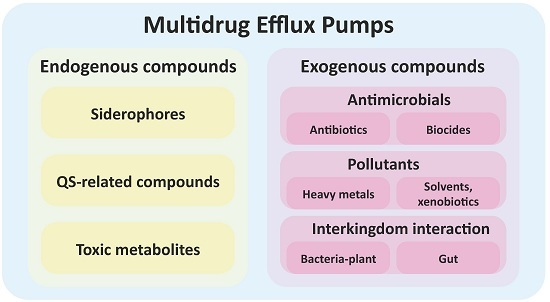

3. Multidrug Efflux Pumps Are Not Just Antibiotic Resistance Elements

4. The Role of Efflux Pumps on Biocide Resistance

5. The Functional Role of Multidrug Efflux Pumps in Non-Clinical Environments: Bacteria-Plant Interactions

6. Induction of the Expression of Efflux Pumps

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMurry, L.; Petrucci, R.E., Jr.; Levy, S.B. Active efflux of tetracycline encoded by four genetically different tetracycline resistance determinants in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 3974–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.L.; Sanchez, M.B.; Martinez-Solano, L.; Hernandez, A.; Garmendia, L.; Fajardo, A.; Alvarez-Ortega, C. Functional role of bacterial multidrug efflux pumps in microbial natural ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.L.; Fajardo, A.; Garmendia, L.; Hernandez, A.; Linares, J.F.; Martinez-Solano, L.; Sanchez, M.B. A global view of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, H.; Takatsuka, Y. Mechanisms of RND multidrug efflux pumps. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1794, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, H. Multidrug Resistance in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bambeke, F.; Michot, J.M.; Tulkens, P.M. Antibiotic efflux pumps in eukaryotic cells: Occurrence and impact on antibiotic cellular pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and toxicodynamics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, R.D.; Lamping, E.; Holmes, A.R.; Niimi, K.; Baret, P.V.; Keniya, M.V.; Tanabe, K.; Niimi, M.; Goffeau, A.; Monk, B.C. Efflux-mediated antifungal drug resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 291–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiker, H.A.; Pringle, S.J.; Abdel-Muhsin, A.; Mackinnon, M.; Hunt, P.; Walliker, D. High-level chloroquine resistance in Sudanese isolates of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with mutations in the chloroquine resistance transporter gene pfcrt and the multidrug resistance Gene pfmdr1. J. Infect. Dis. 2001, 183, 1535–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, J.L.; Duque, E.; Gallegos, M.T.; Godoy, P.; Ramos-Gonzalez, M.I.; Rojas, A.; Teran, W.; Segura, A. Mechanisms of solvent tolerance in Gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2002, 56, 743–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgurskaya, H.I.; Nikaido, H. Multidrug resistance mechanisms: Drug efflux across two membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 37, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nies, D.H. Efflux-mediated heavy metal resistance in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubelski, J.; Konings, W.N.; Driessen, A.J. Distribution and physiology of ABC-type transporters contributing to multidrug resistance in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007, 71, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.T.; Gratwick, K.S.; Kollman, J.; Park, D.; Nies, D.H.; Goffeau, A.; Saier, M.H., Jr. The RND permease superfamily: An ancient, ubiquitous and diverse family that includes human disease and development proteins. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 1, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.J.; Saier, M.H., Jr. SMR-type multidrug resistance pumps. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2001, 4, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Law, C.J.; Maloney, P.C.; Wang, D.N. Ins and outs of major facilitator superfamily antiporters. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 62, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, T.; Tsuchiya, T. Multidrug efflux transporters in the MATE family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1794, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, H. Structure and mechanism of RND-type multidrug efflux pumps. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 2011, 77, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lorca, G.L.; Barabote, R.D.; Zlotopolski, V.; Tran, C.; Winnen, B.; Hvorup, R.N.; Stonestrom, A.J.; Nguyen, E.; Huang, L.W.; Kim, D.S.; et al. Transport capabilities of eleven Gram-positive bacteria: Comparative genomic analyses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1768, 1342–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, M.J.; Brenwald, N.P.; Wise, R. Identification of an efflux pump gene, pmrA, associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ubukata, K.; Itoh-Yamashita, N.; Konno, M. Cloning and expression of the norA gene for fluoroquinolone resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989, 33, 1535–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Ortega, C.; Olivares, J.; Martínez, J.L. RND multidrug efflux pumps: What are they good for? Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.L. The role of natural environments in the evolution of resistance traits in pathogenic bacteria. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2009, 276, 2521–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benveniste, R.; Davies, J. Aminoglycoside antibiotic-inactivating enzymes in actinomycetes similar to those present in clinical isolates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 2276–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J. Inactivation of antibiotics and the dissemination of resistance genes. Science 1994, 264, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.M.; Levy, S.B. Amplifiable resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and other antibiotics in Escherichia coli: Involvement of a non-plasmid-determined efflux of tetracycline. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 155, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grkovic, S.; Brown, M.H.; Skurray, R.A. Transcriptional regulation of multidrug efflux pumps in bacteria. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 12, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, L.; Hancock, R.E. Adaptive and mutational resistance: Role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Z.; Nikaido, H. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria: An update. Drugs 2009, 69, 1555–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, K. Efflux pumps as antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. Ann. Med. 2007, 39, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piddock, L.J. Clinically relevant chromosomally encoded multidrug resistance efflux pumps in bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, L.; Breidenstein, E.B.; Hancock, R.E. Creeping baselines and adaptive resistance to antibiotics. Drug Resist. Updat 2011, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Suarez, J.V.; Martinez, J.L.; Lopez de Goicoechea, M.J.; Perez-Diaz, J.C.; Baquero, F.; Meseguer, M.; Linares, J. Acquisition of antibiotic resistance plasmids in vivo by extraintestinal Salmonella spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1987, 20, 452–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Yokota, S.; Okubo, T.; Ishihara, K.; Ueno, H.; Muramatsu, Y.; Fujii, N.; Tamura, Y. Contribution of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump to high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from dogs and humans. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2013, 75, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakzad, I.; Zayyen Karin, M.; Taherikalani, M.; Boustanshenas, M.; Lari, A.R. Contribution of AcrAB efflux pump to ciprofloxacin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from burn patients. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmidis, C.; Schindler, B.D.; Jacinto, P.L.; Patel, D.; Bains, K.; Seo, S.M.; Kaatz, G.W. Expression of multidrug resistance efflux pump genes in clinical and environmental isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2012, 40, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llanes, C.; Hocquet, D.; Vogne, C.; Benali-Baitich, D.; Neuwirth, C.; Plesiat, P. Clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa overproducing MexAB-OprM and MexXY efflux pumps simultaneously. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1797–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poonsuk, K.; Tribuddharat, C.; Chuanchuen, R. Simultaneous overexpression of multidrug efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa non-cystic fibrosis clinical isolates. Can. J. Microbiol. 2014, 60, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, V.C.; Okazaki, A.; Avison, M.B. Coordinate hyperproduction of SmeZ and SmeJK efflux pumps extends drug resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 655–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomovskaya, O.; Bostian, K.A. Practical applications and feasibility of efflux pump inhibitors in the clinic—A vision for applied use. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomovskaya, O.; Lee, A.; Hoshino, K.; Ishida, H.; Mistry, A.; Warren, M.S.; Boyer, E.; Chamberland, S.; Lee, V.J. Use of a genetic approach to evaluate the consequences of inhibition of efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marquez, B. Bacterial efflux systems and efflux pumps inhibitors. Biochimie 2005, 87, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomovskaya, O.; Watkins, W. Inhibition of efflux pumps as a novel approach to combat drug resistance in bacteria. J. Mol. Microbio.l Biotechnol. 2001, 3, 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, J.; Martinez, J.L. Clinical impact of the over-expression of efflux pump in nonfermentative Gram-negative bacilli, development of efflux pump inhibitors. Curr. Drug Targets 2008, 9, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares, J.; Bernardini, A.; Garcia-Leon, G.; Corona, F.; Martinez, J.L. The intrinsic resistome of bacterial pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, X.Z.; Mistry, A.; Srikumar, R.; Zhang, L.; Lomovskaya, O.; Poole, K. Influence of the TonB energy-coupling protein on efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 2225–2231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lomovskaya, O.; Warren, M.S.; Lee, A.; Galazzo, J.; Fronko, R.; Lee, M.; Blais, J.; Cho, D.; Chamberland, S.; Renau, T.; et al. Identification and characterization of inhibitors of multidrug resistance efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Novel agents for combination therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahamoud, A.; Chevalier, J.; Davin-Regli, A.; Barbe, J.; Pages, J.M. Quinoline derivatives as promising inhibitors of antibiotic efflux pump in multidrug resistant Enterobacter aerogenes isolates. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 843–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, P.; Le, U.; Martinez, J.L. The efflux pump inhibitor Phe-Arg-beta-naphthylamide does not abolish the activity of the Stenotrophomonas maltophilia SmeDEF multidrug efflux pump. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 1042–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, K.; Ishida, Y.; Ohtsuka, M.; Kawato, H.; Yoshida, K.; Yokomizo, Y.; Hosono, S.; Ohta, T.; Hoshino, K.; Ishida, H.; et al. MexAB-OprM-specific efflux pump inhibitors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Part 1: Discovery and early strategies for lead optimization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 4201–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, K.; Ishida, Y.; Ohtsuka, M.; Kawato, H.; Yoshida, K.; Yokomizo, Y.; Ohta, T.; Hoshino, K.; Otani, T.; Kurosaka, Y.; et al. MexAB-OprM specific efflux pump inhibitors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Part 2: Achieving activity in vivo through the use of alternative scaffolds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 4205–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Nakayama, K.; Ohtsuka, M.; Kuru, N.; Yokomizo, Y.; Sakamoto, A.; Takemura, M.; Hoshino, K.; Kanda, H.; Nitanai, H.; et al. MexAB-OprM specific efflux pump inhibitors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Part 7: Highly soluble and in vivo active quaternary ammonium analogue D13–9001, a potential preclinical candidate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 7087–7097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilla, M.A.; Espinosa-Urgel, M.; Rodriguez-Herva, J.J.; Ramos, J.L.; Ramos-Gonzalez, M.I. Genomic analysis reveals the major driving forces of bacterial life in the rhizosphere. Genome Biol. 2007, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Leon, G.; Hernandez, A.; Hernando-Amado, S.; Alavi, P.; Berg, G.; Martinez, J.L. A function of SmeDEF, the major quinolone resistance determinant of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, is the colonization of plant roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 4559–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegos, G.; Stermitz, F.R.; Lomovskaya, O.; Lewis, K. Multidrug pump inhibitors uncover remarkable activity of plant antimicrobials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 3133–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavri, M.; Piddock, L.J.; Gibbons, S. Bacterial efflux pump inhibitors from natural sources. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 59, 1247–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohene-Agyei, T.; Mowla, R.; Rahman, T.; Venter, H. Phytochemicals increase the antibacterial activity of antibiotics by acting on a drug efflux pump. Microbiol. Open 2014, 3, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Jia, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Total Alkaloids of Sophorea alopecuroides-Induced Down-regulation of AcrAB-ToLC Efflux Pump Reverses Susceptibility to Ciprofloxacin in Clinical Multidrug Resistant Escherichia coli isolates. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holler, J.G.; Christensen, S.B.; Slotved, H.C.; Rasmussen, H.B.; Guzman, A.; Olsen, C.E.; Petersen, B.; Molgaard, P. Novel inhibitory activity of the Staphylococcus aureus NorA efflux pump by a kaempferol rhamnoside isolated from Persea lingue Nees. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zechini, B.; Versace, I. Inhibitors of multidrug resistant efflux systems in bacteria. Recent Pat. Antiinfect. Drug Discov. 2009, 4, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, I. New developments in tetracycline antibiotics: Glycylcyclines and tetracycline efflux pump inhibitors. Drug Resist. Updat 2002, 5, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, D.J.; Morrissey, I.; Bakker, S.; Morris, L.; Buckridge, S.; Felmingham, D. Molecular epidemiology of multiresistant Streptococcus pneumoniae with both erm(B)- and mef(A)-mediated macrolide resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Z.; Nikaido, H.; Poole, K. Role of mexA-mexB-oprM in antibiotic efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 1948–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Cook, D.N.; Alberti, M.; Pon, N.G.; Nikaido, H.; Hearst, J.E. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 16, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, E.; Segura, A.; Mosqueda, G.; Ramos, J.L. Global and cognate regulators control the expression of the organic solvent efflux pumps TtgABC and TtgDEF of Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teran, W.; Felipe, A.; Segura, A.; Rojas, A.; Ramos, J.L.; Gallegos, M.T. Antibiotic-dependent induction of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E TtgABC efflux pump is mediated by the drug binding repressor TtgR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3067–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganas, P.; Mihasan, M.; Igloi, G.L.; Brandsch, R. A two-component small multidrug resistance pump functions as a metabolic valve during nicotine catabolism by Arthrobacter nicotinovorans. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.Z.; Poole, K. Organic solvent-tolerant mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa display multiple antibiotic resistance. Can. J. Microbiol. 1999, 45, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, A.; Rojo, F.; Martinez, J.L. Environmental and clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa show pathogenic and biodegradative properties irrespective of their origin. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 1, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, C.; Levy, S.B. Regulation of acrAB expression by cellular metabolites in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiyama, T.; Nishino, K. AcrB, AcrD, and MdtABC multidrug efflux systems are involved in enterobactin export in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, D.E.; Young, K.D. Accumulation of periplasmic enterobactin impairs the growth and morphology of Escherichia coli tolC mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 91, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, L.E.; Price-Whelan, A.; Petersen, A.; Whiteley, M.; Newman, D.K. The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 61, 1308–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aendekerk, S.; Diggle, S.P.; Song, Z.; Hoiby, N.; Cornelis, P.; Williams, P.; Camara, M. The MexGHI-OpmD multidrug efflux pump controls growth, antibiotic susceptibility and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa via 4-quinolone-dependent cell-to-cell communication. Microbiology 2005, 151, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares, J.; Alvarez-Ortega, C.; Linares, J.F.; Rojo, F.; Kohler, T.; Martinez, J.L. Overproduction of the multidrug efflux pump MexEF-OprN does not impair Pseudomonas aeruginosa fitness in competition tests, but produces specific changes in bacterial regulatory networks. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1968–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, K.; Passador, L.; Srikumar, R.; Tsang, E.; Nezezon, J.; Poole, K. Influence of the MexAB-OprM multidrug efflux system on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 5443–5447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Minagawa, S.; Inami, H.; Kato, T.; Sawada, S.; Yasuki, T.; Miyairi, S.; Horikawa, M.; Okuda, J.; Gotoh, N. RND type efflux pump system MexAB-OprM of Pseudomonas aeruginosa selects bacterial languages, 3-oxo-acyl-homoserine lactones, for cell-to-cell communication. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, P.; Linares, J.F.; Ruiz-Diez, B.; Campanario, E.; Navas, A.; Baquero, F.; Martinez, J.L. Fitness of in vitro selected Pseudomonas aeruginosa nalB and nfxB multidrug resistant mutants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 50, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekiya, H.; Mima, T.; Morita, Y.; Kuroda, T.; Mizushima, T.; Tsuchiya, T. Functional cloning and characterization of a multidrug efflux pump, mexHI-opmD, from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutant. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2990–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A.; Sazawal, S.; Pradhan, A.; Ramji, S.; Opiyo, N. Chlorhexidine skin or cord care for prevention of mortality and infections in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echols, K.; Graves, M.; LeBlanc, K.G.; Marzolf, S.; Yount, A. Role of antiseptics in the prevention of surgical site infections. Dermatol. Surg. 2015, 41, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karki, S.; Cheng, A.C. Impact of non-rinse skin cleansing with chlorhexidine gluconate on prevention of healthcare-associated infections and colonization with multi-resistant organisms: A systematic review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012, 82, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, A.E.; Larson, E.L.; Levy, S.B. Consumer antibacterial soaps: Effective or just risky? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 45 (Suppl. S2), S137–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, S.B. Active efflux, a common mechanism for biocide and antibiotic resistance. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 31, 65S–71S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, A.D. Whither triclosan? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 53, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.E.; Maillard, J.Y.; Russell, A.D.; Catrenich, C.E.; Charbonneau, D.L.; Bartolo, R.G. Development of bacterial resistance to several biocides and effects on antibiotic susceptibility. J. Hosp. Infect. 2003, 55, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.L.; Coque, T.M.; Baquero, F. What is a resistance gene? Ranking risk in resistomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, I.; Oggioni, M.R.; Knight, D.; Curiao, T.; Coque, T.; Kalkanci, A.; Martinez, J.L. Evaluation of Epidemiological Cut-Off Values Indicates that Biocide Resistant Subpopulations Are Uncommon in Natural Isolates of Clinically-Relevant Microorganisms. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, J.R.; Carrico, J.A.; Knight, D.; Martinez, J.L.; Morrissey, I.; Oggioni, M.R.; Freitas, A.T. The use of machine learning methodologies to analyse antibiotic and biocide susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maillard, J.Y. Bacterial target sites for biocide action. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 31, 16S–27S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, L.P.; Cooles, S.W.; Coldham, N.G.; Penuela, E.G.; Mott, A.C.; Woodward, M.J.; Piddock, L.J.V.; Webber, M. Commonly used farm disinfectants can select for mutant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with decreased susceptibility to biocides and antibiotics without compromising virulence. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villagra, N.A.; Hidalgo, A.A.; Santiviago, C.A.; Saavedra, C.P.; Mora, G.C. SmvA, and not AcrB, is the major efflux pump for acriflavine and related compounds in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 62, 1273–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMarco, C.E.; Cushing, L.A.; Frempong-Manso, E.; Seo, S.M.; Jaravaza, T.A.; Kaatz, G.W. Efflux-related resistance to norfloxacin, dyes, and biocides in bloodstream isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3235–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuanchuen, R.; Narasaki, C.T.; Schweizer, H.P. The MexJK efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires OprM for antibiotic efflux but not for efflux of triclosan. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 5036–5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuanchuen, R.; Beinlich, K.; Hoang, T.T.; Becher, A.; Karkhoff-Schweizer, R.R.; Schweizer, H.P. Cross-resistance between triclosan and antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by multidrug efflux pumps: Exposure of a susceptible mutant strain to triclosan selects nfxB mutants overexpressing MexCD-OprJ. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, Y. Induction of mexCD-oprJ operon for a multidrug efflux pump by disinfectants in wild-type Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 991–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braoudaki, M.; Hilton, A.C. Low level of cross-resistance between triclosan and antibiotics in Escherichia coli K-12 and E. coli O55 compared to E. coli O157. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 235, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurry, L.M.; Oethinger, M.; Levy, S.B. Overexpression of marA, soxS, or acrAB produces resistance to triclosan in laboratory and clinical strains of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998, 166, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, P.; Moreno, E.; Martinez, J.L. The biocide triclosan selects Stenotrophomonas maltophilia mutants that overproduce the SmeDEF multidrug efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 781–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huet, A.A.; Raygada, J.L.; Mendiratta, K.; Seo, S.M.; Kaatz, G.W. Multidrug efflux pump overexpression in Staphylococcus aureus after single and multiple in vitro exposures to biocides and dyes. Microbiology 2008, 154, 3144–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash Gnanadhas, D.; Amol Marathe, S.; Chakravortty, D. Biocides—Resistance, cross-resistance mechanisms and assessment. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2013, 22, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraise, A.P. Biocide abuse and antimicrobial resistance—A cause for concern? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 49, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCENIHR. Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks SCENIHR Assessment of the Antibiotic Resistance Effects of Biocides; European Commission. Health & Consumer Protection DG: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Cremers, C.M.; Jakob, U.; Love, N.G. Chlorinated phenols control the expression of the multidrug resistance efflux pump MexAB-OprM in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by interacting with NalC. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 79, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, J.F.; Ghosh, S.; Ikuma, K.; Stevens, A.M.; Love, N.G. Chlorinated phenol-induced physiological antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.Z.; Poole, K. SmeDEF multidrug efflux pump contributes to intrinsic multidrug resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 3497–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.; Mate, M.J.; Sanchez-Diaz, P.C.; Romero, A.; Rojo, F.; Martinez, J.L. Structural and Functional Analysis of SmeT, the Repressor of the Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Multidrug Efflux Pump SmeDEF. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 14428–14438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.; Ruiz, F.M.; Romero, A.; Martinez, J.L. The binding of triclosan to SmeT, the repressor of the multidrug efflux pump SmeDEF, induces antibiotic resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, M.B.; Decorosi, F.; Viti, C.; Oggioni, M.R.; Martinez, J.L.; Hernandez, A. Predictive Studies Suggest that the Risk for the Selection of Antibiotic Resistance by Biocides Is Likely Low in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youenou, B.; Favre-Bonte, S.; Bodilis, J.; Brothier, E.; Dubost, A.; Muller, D.; Nazaret, S. Comparative Genomics of Environmental and Clinical Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Strains with Different Antibiotic Resistance Profiles. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 2484–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinidis, K.T.; Tiedje, J.M. Trends between gene content and genome size in prokaryotic species with larger genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 3160–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burse, A.; Weingart, H.; Ullrich, M.S. NorM, an Erwinia amylovora multidrug efflux pump involved in in vitro competition with other epiphytic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshima, K.; Hidaka, T.; Wei, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Minamisawa, K.; Mitsui, H.; Itakura, M.; Kaneko, T.; Tabata, S.; Saeki, K.; et al. Involvement of a novel genistein-inducible multidrug efflux pump of Bradyrhizobium japonicum early in the interaction with Glycine max (L.) Merr. Microb. Environ. 2013, 28, 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, P.; Felipe, A.; Michan, C.; Gallegos, M.T. Induction of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 MexAB-OprM multidrug efflux pump by flavonoids is mediated by the repressor PmeR. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 2011, 24, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, J.D.; Kado, C.I.; Phillips, D.A. An isoflavonoid-inducible efflux pump in Agrobacterium tumefaciens is involved in competitive colonization of roots. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 3107–3113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rossbach, S.; Kunze, K.; Albert, S.; Zehner, S.; Gottfert, M. The Sinorhizobium meliloti EmrAB efflux system is regulated by flavonoids through a TetR-like regulator (EmrR). Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 2014, 27, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burse, A.; Weingart, H.; Ullrich, M.S. The phytoalexin-inducible multidrug efflux pump AcrAB contributes to virulence in the fire blight pathogen, Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 2004, 17, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Karablieh, N.; Weingart, H.; Ullrich, M.S. The outer membrane protein TolC is required for phytoalexin resistance and virulence of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pletzer, D.; Weingart, H. Characterization and regulation of the resistance-nodulation-cell division-type multidrug efflux pumps MdtABC and MdtUVW from the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.R.; Marques, A.T.; Becker, J.D.; Moreira, L.M. The Sinorhizobium meliloti EmrR regulator is required for efficient colonization of Medicago sativa root nodules. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 2014, 27, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eda, S.; Mitsui, H.; Minamisawa, K. Involvement of the smeAB multidrug efflux pump in resistance to plant antimicrobials and contribution to nodulation competitiveness in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2855–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, A.; Koch, M.; Pessi, G.; Muller, A.J.; Balsiger, S.; Hennecke, H.; Fischer, H.M. Host-specific symbiotic requirement of BdeAB, a RegR-controlled RND-type efflux system in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 312, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravirala, R.S.; Barabote, R.D.; Wheeler, D.M.; Reverchon, S.; Tatum, O.; Malouf, J.; Liu, H.; Pritchard, L.; Hedley, P.E.; Birch, P.R.; et al. Efflux pump gene expression in Erwinia chrysanthemi is induced by exposure to phenolic acids. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 2007, 20, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabote, R.D.; Johnson, O.L.; Zetina, E.; San Francisco, S.K.; Fralick, J.A.; San Francisco, M.J. Erwinia chrysanthemi tolC is involved in resistance to antimicrobial plant chemicals and is essential for phytopathogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 5772–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llama-Palacios, A.; Lopez-Solanilla, E.; Rodriguez-Palenzuela, P. The ybiT gene of Erwinia chrysanthemi codes for a putative ABC transporter and is involved in competitiveness against endophytic bacteria during infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1624–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.L.; Baquero, F. Interactions among strategies associated with bacterial infection: Pathogenicity, epidemicity, and antibiotic resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 647–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, D.; Wang, Z.; James, N.R.; Voss, J.E.; Klimont, E.; Ohene-Agyei, T.; Venter, H.; Chiu, W.; Luisi, B.F. Structure of the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump. Nature 2014, 509, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Alberti, M.; Lynch, C.; Nikaido, H.; Hearst, J.E. The local repressor AcrR plays a modulating role in the regulation of acrAB genes of Escherichia coli by global stress signals. Mol. Microbiol. 1996, 19, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, E.Y.; Bertenthal, D.; Nilles, M.L.; Bertrand, K.P.; Nikaido, H. Bile salts and fatty acids induce the expression of Escherichia coli AcrAB multidrug efflux pump through their interaction with Rob regulatory protein. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.G.; Goldman, J.D.; Demple, B.; Levy, S.B. Role of the acrAB locus in organic solvent tolerance mediated by expression of marA, soxS, or robA in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 6122–6126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Cagliero, C.; Guo, B.; Barton, Y.W.; Maurel, M.C.; Payot, S.; Zhang, Q. Bile salts modulate expression of the CmeABC multidrug efflux pump in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 7417–7424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, E.; Yamaguchi, A.; Nishino, K. AcrAB multidrug efflux pump regulation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by RamA in response to environmental signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 24245–24253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafer, W.M.; Qu, X.; Waring, A.J.; Lehrer, R.I. Modulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptibility to vertebrate antibacterial peptides due to a member of the resistance/nodulation/division efflux pump family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 1829–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulavik, M.C.; Gambino, L.F.; Miller, P.F. The MarR repressor of the multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) operon in Escherichia coli: Prototypic member of a family of bacterial regulatory proteins involved in sensing phenolic compounds. Mol. Med. 1995, 1, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baucheron, S.; Nishino, K.; Monchaux, I.; Canepa, S.; Maurel, M.C.; Coste, F.; Roussel, A.; Cloeckaert, A.; Giraud, E. Bile-mediated activation of the acrAB and tolC multidrug efflux genes occurs mainly through transcriptional derepression of ramA in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 2400–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, E.; Shirosaka, I.; Yamaguchi, A.; Nishino, K. Regulation of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in response to indole and paraquat. Microbiology 2011, 157, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, E.; Ding, H.; Demple, B. Redox signal transduction: Mutations shifting [2Fe-2S] centers of the SoxR sensor-regulator to the oxidized form. Cell 1997, 88, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, E.; Leautaud, V.; Demple, B. The redox-regulated Soxr protein acts from a single DNA site as a repressor and an allosteric activator. Embo. J. 1998, 17, 2629–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Michel, L.O.; Zhang, Q. CmeABC functions as a multidrug efflux system in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2124–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Akiba, M.; Sahin, O.; Zhang, Q. CmeR functions as a transcriptional repressor for the multidrug efflux pump CmeABC in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Pu, X.Y.; Zhang, Q. Salicylate functions as an efflux pump inducer and promotes the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 7128–7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, K. Multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2001, 4, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, T.; Epp, S.F.; Curty, L.K.; Pechere, J.C. Characterization of MexT, the regulator of the MexE-MexF-OprN multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6300–6305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fetar, H.; Gilmour, C.; Klinoski, R.; Daigle, D.M.; Dean, C.R.; Poole, K. mexEF-oprN multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Regulation by the MexT activator in response to nitrosative stress and chloramphenicol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisk, A.; Schurr, J.R.; Wang, G.; Bertucci, D.C.; Marrero, L.; Hwang, S.H.; Hassett, D.J.; Schurr, M.J. Transcriptome analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa after interaction with human airway epithelial cells. Infect. Immunity 2004, 72, 5433–5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, N.; Sakagawa, E.; Ohya, S.; Gotoh, N.; Tsujimoto, H.; Nishino, T. Contribution of the MexX-MexY-oprM efflux system to intrinsic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2242–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, Y.; Eda, S.; Gotoh, N.; Yoshihara, E.; Nakae, T. MexZ-mediated regulation of mexXY multidrug efflux pump expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by binding on the mexZ-mexX intergenic DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 238, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeannot, K.; Sobel, M.L.; El Garch, F.; Poole, K.; Plesiat, P. Induction of the MexXY efflux pump in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on drug-ribosome interaction. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 5341–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piddock, L.J. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps—Not just for resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bina, X.R.; Provenzano, D.; Nguyen, N.; Bina, J.E. Vibrio cholerae rnd family efflux systems are required for antimicrobial resistance, optimal virulence factor production, and colonization of the infant mouse small intestine. Infect. Immunity 2008, 76, 3595–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanassi, D.G.; Cheng, L.W.; Nikaido, H. Active efflux of bile salts by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 2512–2518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buckley, A.M.; Webber, M.A.; Cooles, S.; Randall, L.P.; La Ragione, R.M.; Woodward, M.J.; Piddock, L.J. The acraB-tolC efflux system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium plays a role in pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol. 2006, 8, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baugh, S.; Phillips, C.R.; Ekanayaka, A.S.; Piddock, L.J.; Webber, M.A. Inhibition of multidrug efflux as a strategy to prevent biofilm formation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baugh, S.; Ekanayaka, A.S.; Piddock, L.J.; Webber, M.A. Loss of or inhibition of all multidrug resistance efflux pumps of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium results in impaired ability to form a biofilm. J. Antimirob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2409–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, D.M.; Folster, J.P.; Shafer, W.M.; Jerse, A.E. Regulation of the Mtrc-Mtrd-Mtre efflux-pump system modulates the in vivo fitness of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.H.; Shafer, W.M. The farab-encoded efflux pump mediates resistance of gonococci to long-chained antibacterial fatty acids. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 33, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerse, A.E.; Sharma, N.D.; Simms, A.N.; Crow, E.T.; Snyder, L.A.; Shafer, W.M. A gonococcal efflux pump system enhances bacterial survival in a female mouse model of genital tract infection. Infect. Immunity 2003, 71, 5576–5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Sahin, O.; Michel, L.O.; Zhang, Q. Critical role of multidrug efflux pump cmeABC in bile resistance and in vivo colonization of Campylobacter jejuni. Infect. Immunity 2003, 71, 4250–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakata, Y.; Srikumar, R.; Poole, K.; Gotoh, N.; Suematsu, T.; Kohno, S.; Kamihira, S.; Hancock, R.E.; Speert, D.P. Multidrug efflux systems play an important role in the invasiveness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares, J.F.; Lopez, J.A.; Camafeita, E.; Albar, J.P.; Rojo, F.; Martinez, J.L. Overexpression of the multidrug efflux pumps mexCD-oprJ and mexEF-oprN is associated with a reduction of type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, T.; van Delden, C.; Curty, L.K.; Hamzehpour, M.M.; Pechere, J.C. Overexpression of the Mexef-oprN multidrug efflux system affects cell-to-cell signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5213–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.L.; Blazquez, J.; Baquero, F. Non-canonical mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1994, 13, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blanco, P.; Hernando-Amado, S.; Reales-Calderon, J.A.; Corona, F.; Lira, F.; Alcalde-Rico, M.; Bernardini, A.; Sanchez, M.B.; Martinez, J.L. Bacterial Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Much More Than Antibiotic Resistance Determinants. Microorganisms 2016, 4, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms4010014

Blanco P, Hernando-Amado S, Reales-Calderon JA, Corona F, Lira F, Alcalde-Rico M, Bernardini A, Sanchez MB, Martinez JL. Bacterial Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Much More Than Antibiotic Resistance Determinants. Microorganisms. 2016; 4(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms4010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlanco, Paula, Sara Hernando-Amado, Jose Antonio Reales-Calderon, Fernando Corona, Felipe Lira, Manuel Alcalde-Rico, Alejandra Bernardini, Maria Blanca Sanchez, and Jose Luis Martinez. 2016. "Bacterial Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Much More Than Antibiotic Resistance Determinants" Microorganisms 4, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms4010014

APA StyleBlanco, P., Hernando-Amado, S., Reales-Calderon, J. A., Corona, F., Lira, F., Alcalde-Rico, M., Bernardini, A., Sanchez, M. B., & Martinez, J. L. (2016). Bacterial Multidrug Efflux Pumps: Much More Than Antibiotic Resistance Determinants. Microorganisms, 4(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms4010014