Environmental Impact and Relative Invasiveness of Free-Roaming Domestic Carnivores—a North American Survey of Governmental Agencies

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

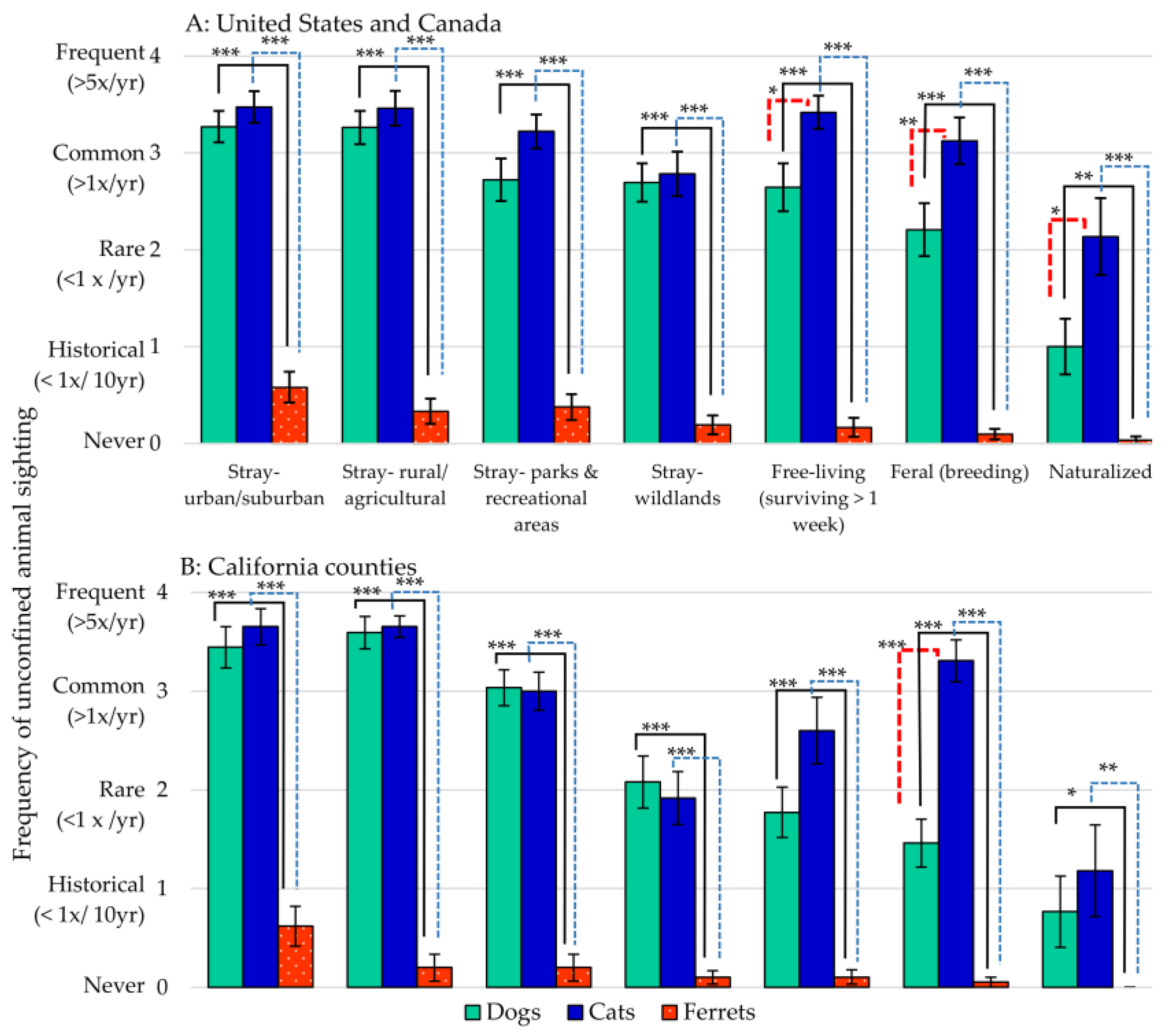

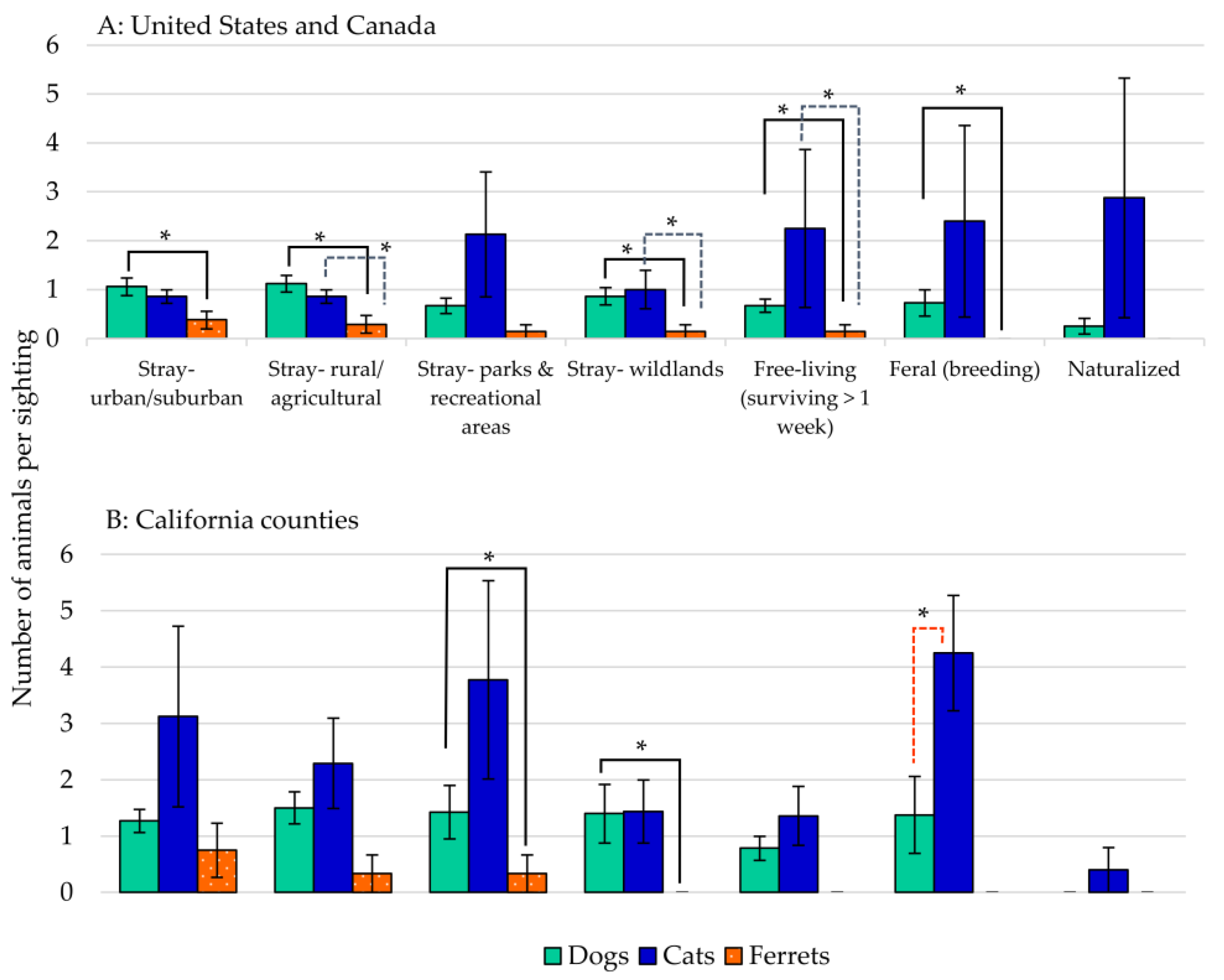

3.1. Sightings of Unconfined Animals

3.2. Sighting of Unconfined Animals—”Degree of Concern”

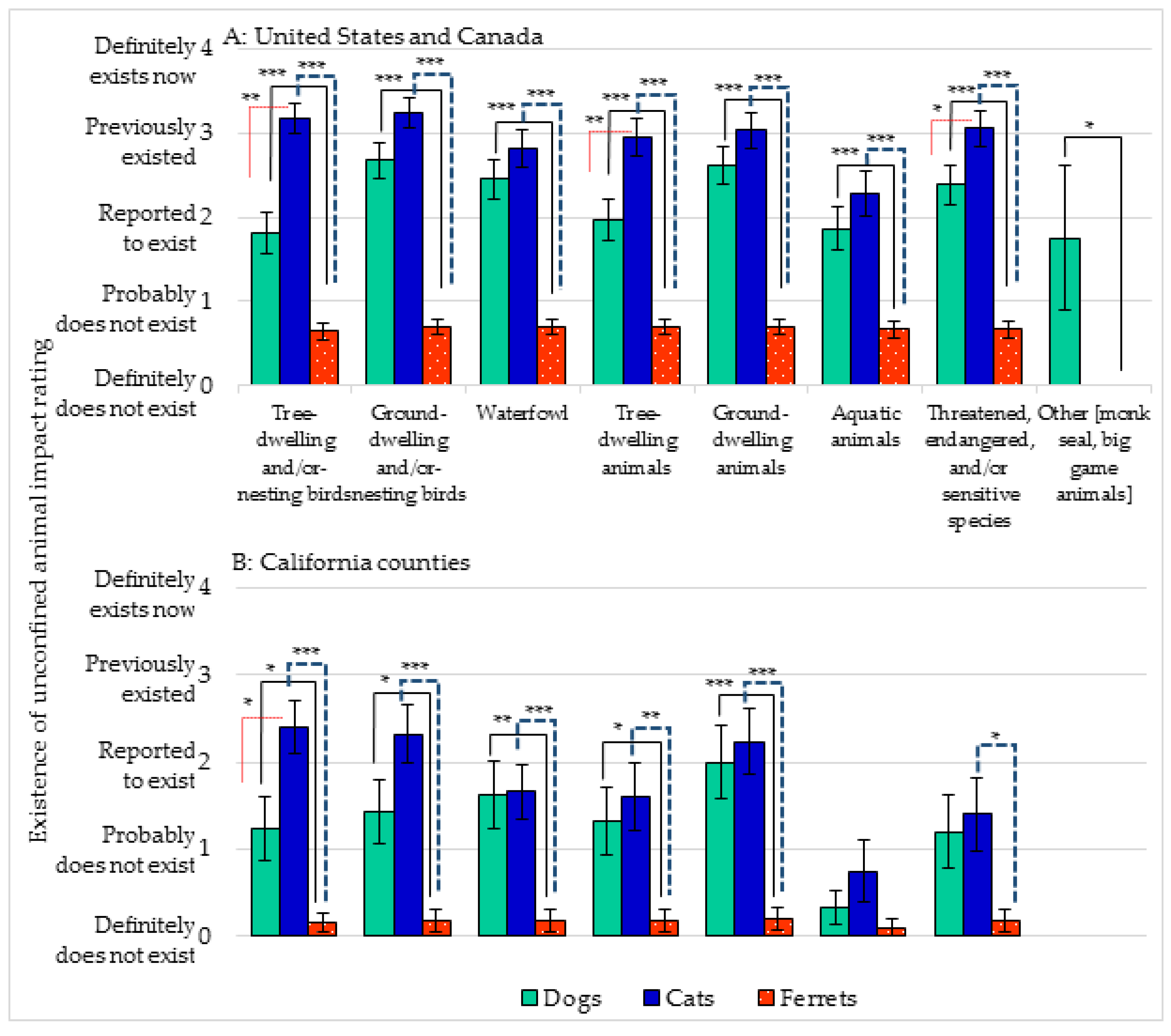

3.3. Impact: Existence of Incidents on Wildlife from Unconfined Animals and Degree of Concern

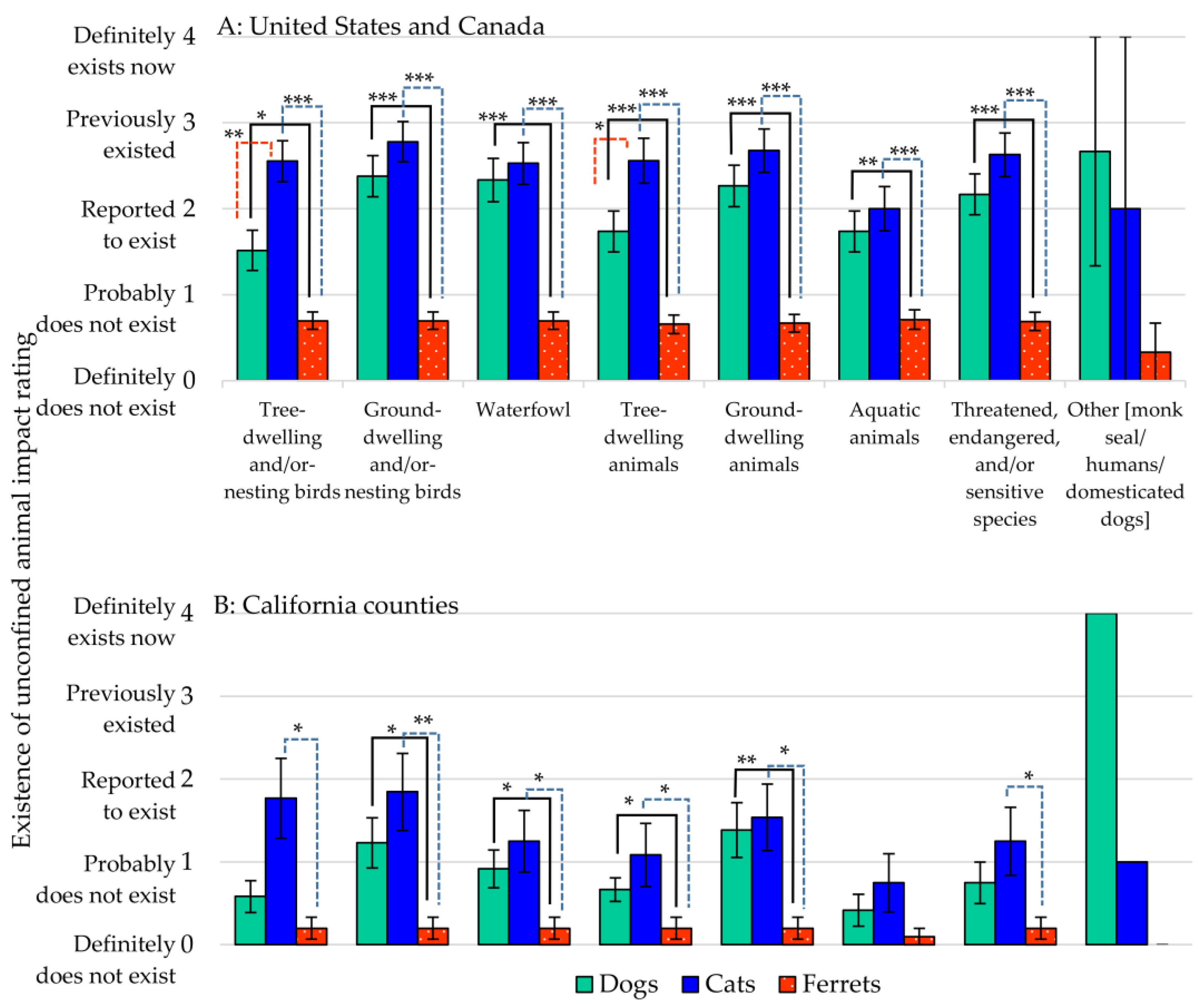

3.4. Impact: Existence of Incidents on Wildlife in Parks—Recreational Areas from Unconfined Animals and Degree of Concern

3.5. Classifications

3.6. Actions Taken

3.7. “Special Concerns”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Executive Order of the President. 81 F.R. 88609–Safeguarding the nation from the impacts of invasive species. Fed. Regist. 2016, 81, 88609–88614. [Google Scholar]

- Elton, C.S. The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.A.; Chew, M.K.; Hobbs, R.J.; Lugo, A.E.; Ewel, J.J.; Vermeji, G.J.; Brown, J.H.; Rosenzweig, M.L.; Gardener, M.R.; Carroll, S.P.; et al. Don’t judge species on their origins. Nature 2011, 474, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Executive Order of the President. 64 FR 6183–Invasive species. Fed. Regist. 1999, 64, 6183–6186. [Google Scholar]

- Canada Invasive Alien Species; No. CW66–394/2004E; Environment Canada: Quebec, Canada, 2004.

- Sato, J.J.; Hosoda, T.; Wolsan, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Yamaoto, M.; Suzuki, H. Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times among Mustelids (Mammalia: Carnivora) based on nucleotide sequences of the nuclear interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein and mitochondrial cytochrome b genes. Zool. Sci. 2003, 20, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigne, J.D.; Guilaine, J.; Debue, K.; Haye, L.; Gerard, P. Early taming of the cat in Cyprus. Science 2004, 304, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handwerk, B. House Cat Origin Traced to Middle Eastern Wildcat Ancestor, 2007. National Geographic News. Available online: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2007/06/070628-cat-ancestor.html (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V.J.; Sawyer, S.K.; Greenfield, D.L.; Germonpré, M.B.; Sablin, M.V.; López-Giráldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes of ancient canids suggest a European origin of domestic dogs. Science 2013, 342, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.G.; Marini, R.P. Biology and Diseases of the Ferret, 3rd Edition; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Ames, IA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- American Kennel Club. Available online: http://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/alaskan-malamute/detail/ (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Godbey, J.; Biggins, D. Recovery of the black-footed ferret: Looking back, looking forward. End. Species Tech. Bull. 1994, 19, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessments. Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States, OTA-F-565; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1993.

- Dauphine´, N.; Cooper, R.J. Impacts of free-ranging domestic cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations. In Tundra to Tropics; Proceedings of the Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference, McAllen, TX, USA, 13–16 February 2008; Rich, T.D., Arizmendi, C., Demarest, D.W., Thompson, C., Eds.; PICCC: Honolulu, Hawaii, 2009; pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.S.; Gipson, P.S. Feral dogs. In The Handbook: Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage; Hygnstrom, S.E., Timm, R.M., Larson, G.E., Eds.; University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1994; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S.; Temple, S.A.; Craven, S.R. Cats and Wildlife: A Conservation Dilemma; University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension Publications: Madison, WI, USA, 1997; Available online: https://web.extension.illinois.edu/wildlife/files/cats_and_wildlife.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Ogan, C.V.; Jurek, R.M. Biology and ecology of feral, free-roaming and stray cats. In Mesocarnivores of Northern California: Biology, Management and Survey Techniques, Workshop Manual; Harris, J.E., Ogan, C.V., Eds.; Humbolt State University: Arcata, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P.J.; Bentley, A.J.; Ansell, R.J.; Harris, S. Impact of predation by domestic cats Felis catus in an urban area. Mammal Rev. 2005, 35, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Park Service (NPS). Available online: https://www.nps.gov/ever/learn/education/upload/backgroundinformation.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Mcruer, D.L.; Gray, L.C.; Horne, L.-A.; Clark, E.E. Free-roaming cat interactions with wildlife admitted to a wildlife hospital. J. Wildl. Manag. 2016, 81, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, M. National Geographic News. Available online: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/08/0821_030821_straydogs.html (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Pimental, D. Environmental and economic costs of vertebrate species invasions into the United States. In Managing Vertebrate Invasive Species, Proceedings of an international symposium, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 7–9 August 2007; Witmer, G.W., Pitt, W.C., Fagerstone, K.A., Eds.; USDA/APHIS Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2007; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Loss, S.R.; Will, T.; Marra, P.P. The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, M. National Geographic News. Available online: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0907_040907_feralcats.html (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Bergman, D.S.; Breck, S.; Bender, S. Dogs gone wild: Feral dog damage in the United States. In National Wildlife Research Center—Staff, Proceedings of the 13th WDM Conference, Saratoga Springs, New York, USA, 4–6 May 2009; Boulanger, J.R., Ed.; USDA/APHIS Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2009; pp. 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Demarest, D.W.; Thompson, C. Animal Law in Canada. Available online: http://www.animallaw.ca/ (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Wisch, R.F. Overview of Local and State Dog Laws. 2014. Available online: https://www.animallaw.info/intro/state-and-local-dog-laws (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Wisch, R.F. Detailed Discussion of State Cat Laws. 2005. Available online: https://www.animallaw.info/article/detailed-discussion-state-cat-laws (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- American Ferret Association Home Page; Gaines, D. Summary of State and Territory-Level Ferret Regulations 2009. Available online: http://www.ferret.org/pdfs/general/2009-StateByState.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- King, C.M. Immigrant Killers: Introduced Predators and the Conservation of Birds in New Zealand. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T.G.; Whisson, D.A. Potential risks associated with the legalization of exotic predators such as the ferret (Mustela putorius furo) in California. In Proceedings of the 18th Vertebrate Pest Conference, Costa Mesa, California, 2–5 March 1998; Baker, R.O., Crabb, A.C., Eds.; University of California, Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 62, pp. 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jurek, R.M.; Ryan, P. 1996–97 Nationwide Ferret Survey of State Wildlife Agencies; Habitat Conservation and Planning Branch, Species Conservation and Recovery Program Report; California Department of Fish and Game: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 1–69.

- Lenth, B.E.; Knight, R.L.; Brennan, M.E. The effects of dogs on wildlife communities. Nat. Areas J. 2008, 28, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frincham, J.E. Response rates and responsiveness for surveys, standards, and the journal. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ponto, J. Understanding and evaluating survey research. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2015, 6, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayhan, H.O. Memory recall errors in retrospective surveys: A reverse record check study. Qual. Quant. 2004, 38, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, J. Response problems in surveys—Improving the response and minimising the load. In Proceedings of the UNSD Regional Seminar on ‘Good Practices in the Organization and Management of Statistical Systems’ for ASEAN countries, Yangon, Myanmar, 11–13 December 2002; UNSD: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/statorg/Workshops/Yangon/Session4_Surveys_Cornish_Paper.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Huss, R.J. No Pets Allowed: Housing Issues and Companion Animals; Animal Law Review at Lewis & Clark Law School: Portland, OR, USA, 2005; Volume 11, pp. 69–121. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). Available online: http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nycha/downloads/pdf/Pet_GM_Policy_Overview_2010_04_d2.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Umbach, K.W. Ferrets: A Selective Overview of Issues and Options; California Research Bureau, California State Library: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1997; Volume 4, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.library.ca.gov/CRB/97/notes/v4n3.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). Available online: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/living-with-wildlife/restricted-pet-species (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Boni, S.E. Anthropomorphism: How it affects the human–Canine bond. J. Appl. Comp. Anim. Behav. 2008, 2, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, B. The Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/12/the-case-against-cats/505838/ (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Kellert, S.R. American attitudes toward and knowledge of animals: An update. Int. J. Stud. Anim. Probl. 1980, 1, 87–119. [Google Scholar]

- American Board of Veterinary Practitioners. Available online: http://abvp.com/veterinary-certification/recognized-veterinary-specialties/ (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- California Code of Regulations. Title 14, Section 641.671. Importation, transportation and possession of live restricted animals. California Natural Resources Agency Department of Fish and Wildlife: Sacramento, CA, USA.

- Nemec, J. GRIT. Available online: http://www.grit.com/animals/water-buffalo-herds-growing-in-the-united-states (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Anderson, S. The New York Times Magazine. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/14/magazine/buffalo-mozzarella-craig-ramini.html?mcubz=0 (accessed on 8 September 2017).

- Palmer, C. Animals in Context; Columbia Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Valéry, L.; Fritz, H.; Lefeuvre, J.C.; Simberloff, D. In search of a real definition of the biological invasion phenomenon itself. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valéry, L.; Fritz, H.; Lefeuvre, J.C.; Simberloff, D. Invasive Species Can Also be Native. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.A. Invasion Biology. In Encyclopaedia of Biological Invasions; Simberloff, D., Rejmanek, M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- The Definitions Subcommittee of the Invasive Species Advisory Committee (ISAC). Invasive Species Definition Clarification and Guidance White Paper; The National Invasive Species Council (NISC): Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 1–11.

| Animal Sightings | Dogs | Cats | Ferrets | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± sem | Mean ± sem | Mean ± sem | ||

| United States and Canada | ||||

| Stray—urban/suburban | 1.06 ± 0.18 | 0.86 ± 0.14 | 0.38 ± 0.18 | ac ns |

| b p < 0.05 | ||||

| Stray—rural/agricultural | 1.12 ± 0.17 | 0.86 ± 0.14 | 0.29 ± 0.18 | a ns |

| bc p < 0.05 | ||||

| Stray—parks & recreational areas | 0.67 ± 0.16 | 2.13 ± 1.28 | 0.14 ± 0.14 | abc ns |

| Stray—wildlands | 0.86 ± 0.18 | 1.00 ± 0.39 | 0.14 ± 0.14 | a ns |

| bc p < 0.05 | ||||

| Free-living (surviving > 1 week) | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 2.25 ± 1.62 | 0.14 ± 0.14 | a ns |

| bc p < 0.05 | ||||

| Feral (breeding) | 0.73 ± 0.27 | 2.40 ± 1.96 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | ac ns |

| b p < 0.05 | ||||

| Naturalized | 0.25 ± 0.16 | 2.88 ± 0.2.45 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | abc ns |

| California Counties | ||||

| Stray Animals—urban/suburban | 1.27 ± 0.20 | 3.13 ± 1.60 | 0.75 ± 0.48 | abc ns |

| Stray Animals—rural/agricultural | 1.50 ± 0.29 | 2.29 ± 0.80 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | abc ns |

| Stray animals—parks & recreational areas | 1.42 ± 0.47 | 3.77 ± 1.76 | 0.33 ± 0.33 | ac ns |

| b p < 0.05 | ||||

| Stray Animals—wildlands | 1.40 ± 0.52 | 1.44 ± 0.56 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | ac ns |

| b p < 0.05 | ||||

| Free-living animals (surviving > 1 week) | 0.79 ± 0.21 | 1.36 ± 0.52 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | abc ns |

| Feral (Breeding) Animals | 1.38 ± 0.68 | 4.25 ± 1.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | ac p < 0.05 |

| b ns | ||||

| Naturalized animals | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.40 ± 0.40 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | ac ns |

| Animal Sightings | Dogs | Cats | Ferrets | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± sem | ¹ Rating Range | Mean ± sem | Rating Range | Mean ± sem | Rating Range | ||

| United States, DC and Canada | |||||||

| Stray-urban/suburban | −1.58 ± 0.09 | (−2)–0 | −1.76 ± 0.08 | (−2)–0 | −0.50 ± 0.12 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Stray-rural/ agricultural | −1.61 ± 0.09 | (−2)–0 | −1.72 ± 0.09 | (−2)–1 | −0.54 ± 0.14 | (−2)–1 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Stray-parks & recreational areas | −1.57 ± 0.08 | (−2)–0 | −1.70 ± 0.09 | (−2)–1 | −0.56 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Stray-wildlands | −1.49 ± 0.10 | (−2)–0 | −1.70 ± 0.07 | (−2)–(−1) | −0.58 ± 0.14 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Free-living (surviving > 1 week) | −1.50 ± 0.10 | (−2)–0 | −1.76 ± 0.08 | (−2)–0 | −0.54 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Feral (Breeding) | −1.53 ± 0.10 | (−2)–0 | −1.83 ± 0.06 | (−2)–(−1) | −0.54 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ p < 0.05 |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Naturalized | −1.03 ± 0.18 | (−2)–2 | −1.61 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | −0.65 ± 0.15 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ p < 0.05 |

| b ns | |||||||

| c p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Overall Means | −1.47 | −1.73 | −0.56 | ||||

| California Counties | |||||||

| Stray-urban/suburban | −1.00 ± 0.19 | (−2)–0 | −1.58 ± 0.16 | (−2)–1 | −0.47 ± 0.19 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Stray-rural/agricultural | −1.74 ± 0.11 | (−2)–0 | −1.44 ± 0.20 | (−2)–2 | −0.47 ± 0.19 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Stray-parks & recreational areas | −1.69 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | −1.36 ± 0.16 | (−2)–1 | −0.50 ± 0.20 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| c p < 0.01 | |||||||

| Stray-wildlands | −1.28 ± 0.16 | (−2)–0 | –1.08 ± 0.19 | (−2)–1 | −0.46 ± 0.22 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| ᵇ p < 0.01 | |||||||

| c p < 0.05 | |||||||

| Free-living (surviving > 1 week) | −1.16 ± 0.18 | (−2)–0 | −1.19 ± 0.20 | (−2)–1 | −0.50 ± 0.23 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.05 | |||||||

| Feral (Breeding) | −1.29 ± 0.18 | (−2)–0 | −1.44 ± 0.20 | (−2)–1 | −0.36 ± 0.20 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.01 | |||||||

| Naturalized | −0.33 ± 0.26 | (−2)–1 | −0.50 ± 0.25 | (−2)–1 | −0.22 ± 0.22 | (−2)–0 | abc ns |

| Overall Means | −1.21 | −1.23 | −0.43 | ||||

| Effects on Wildlife | Dogs | Cats | Ferrets | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± sem | 1 Rating Range | Mean ± sem | Rating Range | Mean ± sem | Rating Range | ||

| United States, DC and Canada | |||||||

| Tree-Dwelling and/or–nesting birds | −0.68 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | −1.78 ± 0.07 | (−2)–(−1) | −0.33 ± 0.14 | (−2)–0 | ac p < 0.001 |

| ᵇ ns | |||||||

| Ground-dwelling and/or–nesting birds | −1.43 ± 0.10 | (−2)–0 | −1.90 ± 0.05 | (−2)–(−1) | −0.56 ± 0.18 | (−2)–0 | abc p < 0.001 |

| Waterfowl | −1.09 ± 0.11 | (−2)–0 | −1.41 ± 0.11 | (−2)–0 | −0.33 ± 0.11 | (−1)–0 | ᵃ p < 0.05 |

| ᵇc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Tree-dwelling animals | −0.75 ± 0.11 | (−2)–0 | −1.28 ± 0.14 | (−2)–0 | −0.44 ± 0.15 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ p < 0.01 |

| ᵇ ns | |||||||

| c p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Ground-dwelling animals | −1.36 ± 0.10 | (−2)–0 | −1.62 ± 0.09 | (−2)–0 | −0.56 ± 0.18 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Aquatic animals | −0.54 ± 0.11 | (−2)–0 | −0.63 ± 0.12 | (−2)–0 | −0.22 ± 0.10 | (−1)–0 | ᵃᵇ ns |

| c p < 0.05 | |||||||

| Threatened, Endangered, and/or Sensitive species | −1.13 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | −1.63 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | −0.63 ± 0.21 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ p < 0.01 |

| ᵇ p < 0.05 | |||||||

| c p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Other (Monk Seal, Big Game Animals) | −1.33 ± 0.33 | (−2)–(−1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ᵇ ns |

| Overall Means | −1.04 | −1.28 | −0.38 | ||||

| California Counties | |||||||

| Tree-Dwelling and/or—nesting birds | −0.11 ± 0.35 | (−2)–2 | −1.64 | (−2)–(−1) | −0.33 | (−1)–0 | ᵃ p < 0.001 |

| ᵇ ns | |||||||

| c p < 0.01 | |||||||

| Ground-dwelling and/or—nesting birds | −1.09 ± 0.28 | (−2)–0 | −1.46 ± 0.18 | (−2)–0 | −0.33 ± 0.33 | (−1)–0 | ᵃᵇ ns |

| c p < 0.05 | |||||||

| Waterfowl | −1.09 ± 0.28 | (−2)–0 | −1.30 ± 0.26 | (−2)–0 | −0.33 ± 0.33 | (−1)–0 | abc ns |

| Tree-dwelling animals | −0.78 ± 0.32 | (−2)–0 | −1.25 ± 0.37 | (−2)–0 | −0.33 ± 0.33 | (−1)–0 | abc ns |

| Ground-dwelling animals | −1.31 ± 0.21 | (−2)–0 | −1.40 ± 0.22 | (−2)–0 | −0.33 ± 0.33 | (−1)–0 | abcns |

| Aquatic animals | −0.50 ± 0.34 | (−2)–0 | −0.86 ± 0.34 | (−2)–0 | −0.33 ± 0.33 | (−1)–0 | abc ns |

| Threatened, Endangered, and/or Sensitive species | −1.30 ± 0.30 | (−2)–0 | −1.44 ± 0.29 | (−2)–0 | −0.33 ± 0.33 | (−1)–0 | abc ns |

| Other (Monk Seal, Big Game Animals) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Overall Means | −0.77 | −1.17 | −0.29 | ||||

| Effects on Parks/Recreational Areas | Dogs | Cats | Ferrets | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± sem | 1 Rating Range | Mean ± sem | Rating Range | Mean ± sem | Rating Range | ||

| United States, DC and Canada | |||||||

| Tree-Dwelling and/or–nesting birds | −0.54 ± 0.12 | (−2)–0 | −1.35 ± 0.16 | (−2)–0 | −0.64 ± 0.17 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ p < 0.001 |

| ᵇ ns | |||||||

| c p < 0.01 | |||||||

| Ground-dwelling and/or–nesting birds | −1.25 ± 0.14 | (−2)–0 | −1.57 ± 0.13 | (−2)–0 | −0.36 ± 0.20 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| ᵇc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Waterfowl | −0.96 ± 0.14 | (−2)–0 | −1.15 ± 0.15 | (−2)–0 | −0.07 ± 0.07 | (−1)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Tree-dwelling animals | −0.43 ± 0.12 | (−2)–0 | −1.20 ± 0.15 | (−2)–0 | −0.23 ± 0.17 | (−2)–0 | ac p < 0.001 |

| ᵇ ns | |||||||

| Ground-dwelling animals | −1.19 ± 0.12 | (−2)–0 | −1.42 ± 0.14 | (−2)–0 | −0.29 ± 0.16 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| bc p < 0.001 | |||||||

| Aquatic animals | −0.45 ± 0.14 | (−2)–0 | −0.45 ± 0.14 | (−2)–0 | −0.13 ± 0.09 | (−1)–0 | abc ns |

| Threatened, Endangered, and/or Sensitive species | −1.12 ± 0.17 | (−2)–0 | −1.44 ± 0.16 | (−2)–0 | −0.43 ± 0.20 | (−2)–0 | ᵃ ns |

| ᵇ p < 0.05 | |||||||

| c p < 0.01 | |||||||

| Other (monk seal/humans/domesticated dogs) | −2.00 | −2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Overall Mean: | −0.99 | −1.23 | −0.31 | ||||

| California Counties | |||||||

| Tree-Dwelling and/or- nesting birds | −0.33 ± 0.33 | (−2)–0 | −1.11 ± 0.31 | (−2)–0 | −0.67 ± 0.67 | (−2)–0 | abc ns |

| Ground-dwelling and/or- nesting birds | −0.89 ± 0.31 | (−2)–0 | −1.33 ± 0.29 | (−2)–0 | −0.67 ± 0.67 | (−2)–0 | abc ns |

| Waterfowl | −0.71 ± 0.36 | (−2)–0 | −1.17 ± 0.40 | (−2)–0 | −0.67 ± 0.67 | (−2)–0 | abc ns |

| Tree-dwelling animals | −0.33 ± 0.33 | (−2)–0 | −1.00 ± 0.45 | (−2)–0 | −0.67 ± 0.67 | (−2)–0 | abc ns |

| Ground-dwelling animals | −0.89 ± 0.26 | (−2)–0 | −1.13 ± 0.30 | (−2)–0 | −0.67 ± 0.67 | (−2)–0 | abc ns |

| Aquatic animals | −0.50 ± 0.34 | (−2)–0 | −0.71 ± 0.36 | (−2)–0 | −0.50 ± 0.50 | (−2)–0 | abc ns |

| Threatened, Endangered, and/or Sensitive species | −1.00 ± 0.38 | (−2)–0 | −1.29 ± 0.36 | (−2)–0 | −0.67 ± 0.67 | (−2)–0 | abc ns |

| Other (monk seal/humans/domesticated dogs) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Overall Mean: | −0.67 | −1.11 | −0.64 | ||||

| Classification | Dogs | Cats | Ferrets |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States, DC and Canada | |||

| “House-pet” or “Companion” | 56 (78%) | 55 (76%) | 39 (54%) |

| “Domestic” or “Domesticated” | 59 (82%) | 58 (81%) | 44 (61%) |

| “Exotic animal” | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 19 (26%) |

| “Non-game” | 9 (13%) | 9 (13%) | 10 (14%) |

| “Fur-bearing” | 0 | 1 (1%) | 8 (11%) |

| “Laboratory” or “Research” | 13 (18%) | 13 (18%) | 9 (13%) |

| “Wild” or Wildlife” | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 7 (10%) |

| “Unlisted” or “Unrestricted” or “Permitted” | 10 (14%) | 9 (13%) | 14 (19%) |

| “Listed” or “Restricted” or “Not permitted” | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) |

| “Restricted, except under a permit” | 0 | 0 | 5 (7%) |

| Other (Please specify in Comments) | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) |

| No Classification | 9 (13%) | 11 (15%) | 12 (17%) |

| California Counties | |||

| “House- pet” or “Companion” | 26 (90%) | 26 (90%) | 3 (10%) |

| “Domestic” or “Domesticated” | 26 (90%) | 25 (86%) | 4 (14%) |

| “Exotic animal” | 0 | 1 (3%) | 17 (59%) |

| “Non-game” | 12 (41%) | 11 (38%) | 9 (31%) |

| “Fur-bearing” | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 8 (28%) |

| “Laboratory” or “Research” | 8 (28%) | 7 (24%) | 3 (10%) |

| “Wild” or Wildlife” | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 8 (28%) |

| “Unlisted” or “Unrestricted” or “Permitted” | 6 (21%) | 6 (21%) | 2 (7%) |

| “Listed” or “Restricted” or “Not permitted” | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 11 (38%) |

| “Restricted, except under a permit” | 1 (3%) | 0 | 12 (41%) |

| Other (Please specify in Comments) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| No Classification | 3 (10%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (7%) |

| Action Taken | Dogs | Cats | Ferrets |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States, DC, and Canada | |||

| None: not considered to be important | 2 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 8 (11%) |

| None: desirable, but not feasible | 12 (17%) | 15 (21%) | 9 (13%) |

| Live trap/take to shelter (assumed lost pet) | 17 (24%) | 15 (21%) | 8 (11%) |

| Live trap/euthanize | 8 (11%) | 10 (14%) | 7 (10%) |

| Live trap/transport (specify destination in Comments) | 7 (10%) | 9 (13%) | 4 (6%) |

| Take by any means | 10 (14%) | 5 (7%) | 4 (6%) |

| Refer to another agency (specify in Comments) | 27 (38%) | 24 (34%) | 19 (27%) |

| Attempt eradication | 3 (4%) | 4 (6%) | 4 (6%) |

| Unknown | 3 (4%) | 4 (6%) | 8 (11%) |

| California Counties | |||

| None: not considered to be important | 1 (3%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| None: desirable, but not feasible | 0 | 4 (12%) | 0 |

| Live trap/take to shelter (assumed lost pet) | 22 (67%) | 18 (55%) | 6 (18%) |

| Live trap/euthanize | 7 (21%) | 7 (21%) | 5 (15%) |

| Live trap/transport (specify destination in Comments) | 4 (12%) | 3 (9%) | 2 (6%) |

| Take by any means | 5 (15%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (12%) |

| Refer to another agency (specify in Comments) | 4 (12%) | 4 (12%) | 13 (40%) |

| Attempt eradication | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lepe, A.; Kaplan, V.; Arreaza, A.; Szpanderfer, R.; Bristol, D.; Sinclair, M.S. Environmental Impact and Relative Invasiveness of Free-Roaming Domestic Carnivores—a North American Survey of Governmental Agencies. Animals 2017, 7, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7100078

Lepe A, Kaplan V, Arreaza A, Szpanderfer R, Bristol D, Sinclair MS. Environmental Impact and Relative Invasiveness of Free-Roaming Domestic Carnivores—a North American Survey of Governmental Agencies. Animals. 2017; 7(10):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7100078

Chicago/Turabian StyleLepe, Ana, Valerie Kaplan, Alirio Arreaza, Robert Szpanderfer, David Bristol, and M. Scott Sinclair. 2017. "Environmental Impact and Relative Invasiveness of Free-Roaming Domestic Carnivores—a North American Survey of Governmental Agencies" Animals 7, no. 10: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7100078

APA StyleLepe, A., Kaplan, V., Arreaza, A., Szpanderfer, R., Bristol, D., & Sinclair, M. S. (2017). Environmental Impact and Relative Invasiveness of Free-Roaming Domestic Carnivores—a North American Survey of Governmental Agencies. Animals, 7(10), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7100078