A Decade of Progress toward Ending the Intensive Confinement of Farm Animals in the United States

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Nature of the Animal Protection Movement from 1980 to 2000

1.1. Henry Spira’s Influence

1.2. Farm Animals and Early Legislative Initiatives

2. The 2002 Florida Gestation Crate Ballot Initiative

The First Confinement Ban

3. Contemporary Farm Animal Protection Work at the HSUS

3.1. Launch of the Campaign

3.2. The Scientific Basis for Farm Animals’ Campaign Work

4. The 2006 Arizona Gestation Crate Ballot Initiative

Proposition 204

5. The Power of Undercover Investigations

5.1. Hallmark/Westland

5.2. Widespread Objectionable Practices

6. California’s Proposition 2

6.1. The Campaign

- (a)

- Lying down, standing up, and fully extending his or her limbs; and

- (b)

- Turning around freely”.

6.2. The Ensuing Legal Activity

7. The 2010 Ohio Ballot Initiative

Countermeasures

8. The Federal Egg Bill

Partnering with Egg Producers

9. Corporate Policy

9.1. Engaging with Major Brands

9.2. The Rise of Corporate Social Responsibility

10. The 2012 Gestation Crate Announcements

10.1. McDonald’s

10.2. The Companies That Followed

11. The Evolving Social Consciousness

11.1. Financial Support for U.S. Animal Protection in the 21st Century

11.2. Further Barometers of Public Sentiment

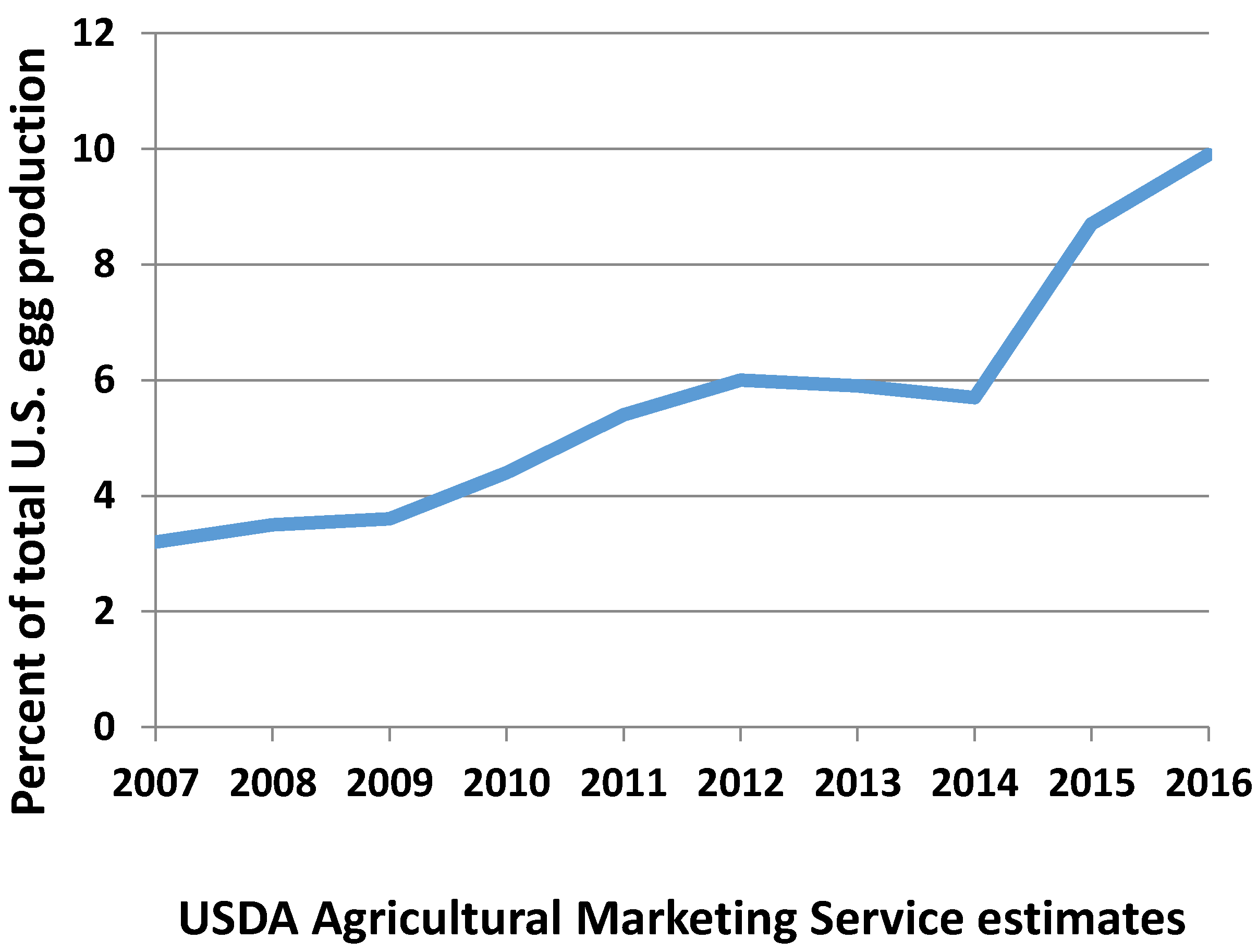

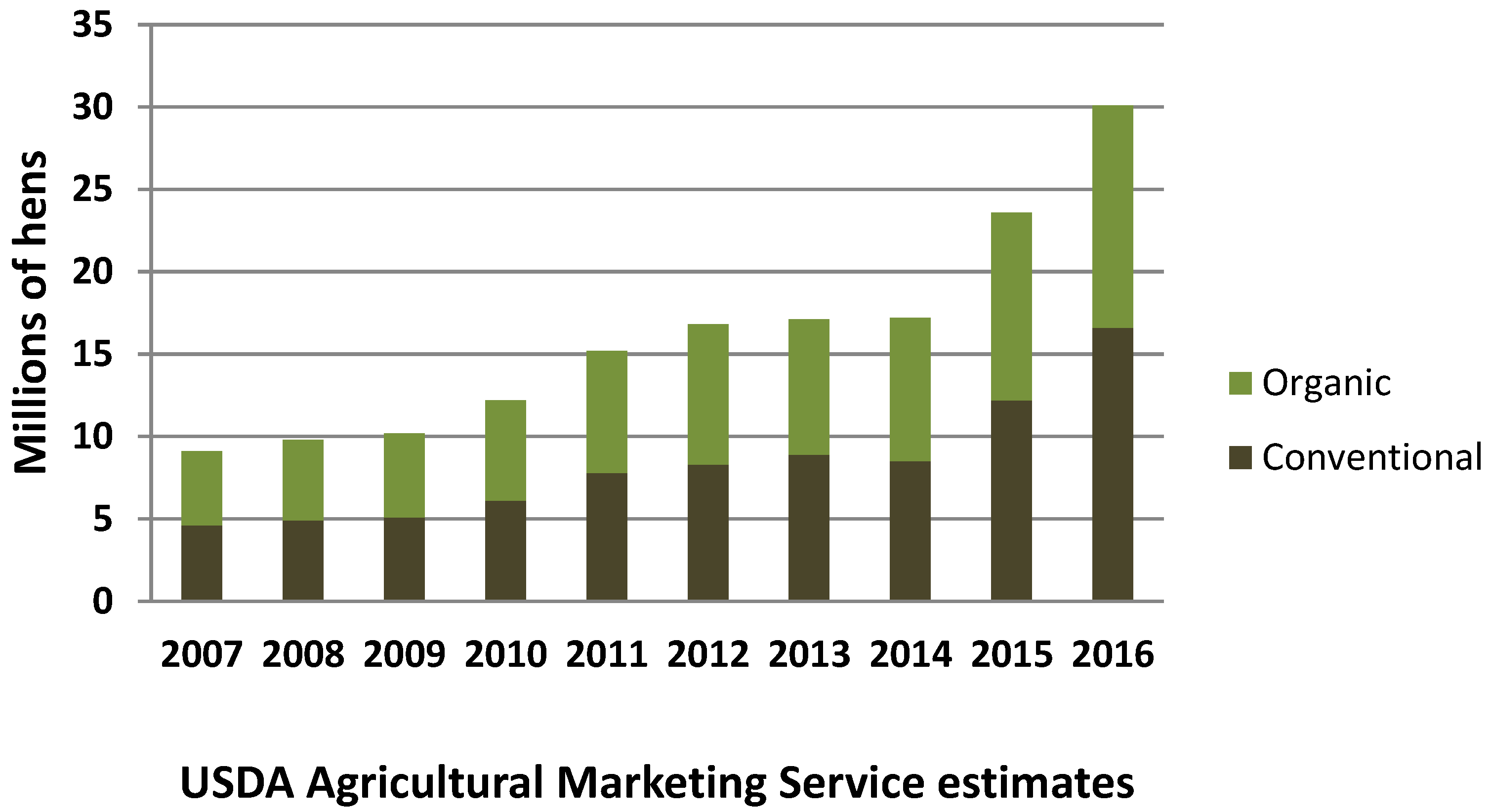

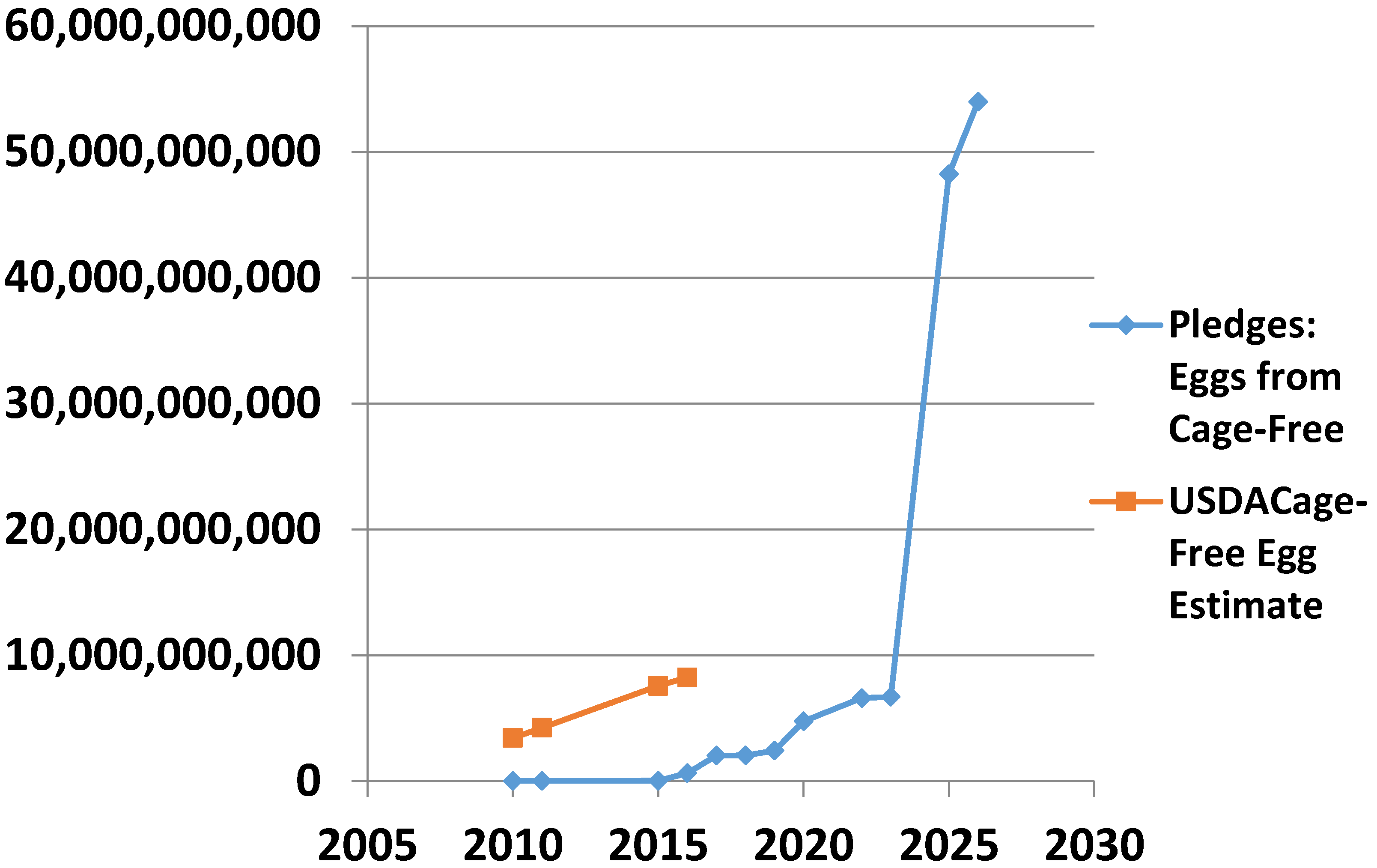

12. The Demise of the Battery Cage in America

12.1. Freeing the Hens

12.2. Pressuring the Holdouts

13. Conclusions: Looking Ahead

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Company | Pledge Date | Annual Egg Usage | Transition Time-Line |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red Robin | 25 May 2009 | 2,000,000 | 2010 |

| Hellman’s Mayonnaise | 24 February 2010 | 350,000,000 | 2020 |

| Hyatt Hotels | 24 May 2011 | 3,000,000 | 2011 |

| Burger King | 25 April 2012 | 1,200,000,000 | 2017 |

| Au Bon Pain | 21 January 2013 | 41,000,000 | 2017 |

| Marriott | 27 January 2013 | 25,600,000 | 2015 |

| Delaware North | 22 October 2014 | 370,000,000 | 2016 |

| Sodexo | 19 February 2015 | 239,000,000 | 2020 |

| Aramark | 12 March 2015 | 215,000,000 | 2020 |

| Centerplate | 23 March 2015 | 600,000 | 2020 |

| King’s Food Markets | 5 April 2015 | 35,000,000 | 2025 |

| Otis Spunkmeyer | 5 April 2015 | 100,000,000 | 2023 |

| Hilton Hotels | 6 April 2015 | 4,100,000 | 2017 |

| WinCo Foods | 25 April 2015 | 85,100,000 | 2025 |

| Revolution Foods | 1 July 2015 | 3,000,000 | 2018 |

| Cheesecake Factory | 28 July 2015 | 6,000,000 | 2020 |

| McDonald’s | 9 September 2015 | 2,000,000,000 | 2025 |

| Starbuck’s | 1 October 2015 | 195,000,000 | 2020 |

| TGI Friday’s | 27 October 2015 | 7,000,000 | 2025 |

| Kellogg’s | 29 October 2015 | 400,000,000 | 2025 |

| Panera Bread | 5 November 2015 | 120,000,000 | 2020 |

| Taco Bell | 16 November 2015 | 130,000,000 | 2016 |

| Jack in the Box/Qdoba | 20 November 2015 | 108,000,000 | 2025 |

| General Mills | 25 November 2015 | 331,000,000 | 2025 |

| Costco | 2 December 2015 | 2,900,000,000 | 2025 |

| Royal Caribbean | 3 December 2015 | 6,900,000 | 2022 |

| Dunkin’ Donuts | 7 December 2015 | 390,000,000 | 2025 |

| Subway | 8 December 2015 | 110,000,000 | 2025 |

| Arby’s | 9 December 2015 | 12,000,000 | 2020 |

| Einstein Bros | 14 December 2015 | 9,000,000 | 2020 |

| Flowers Foods | 14 December 2015 | 100,000,000 | 2025 |

| Peet’s Coffee | 14 December 2015 | 3,000,000 | 2020 |

| Caribou Coffee | 15 December 2015 | 4,000,000 | 2020 |

| Shake Shack | 15 December 2015 | 2,000,000 | 2016 |

| Carnival Corp. | 21 December 2015 | 7,000,000 | 2025 |

| Nestle | 22 December 2015 | 185,000,000 | 2020 |

| Wendy’s | 4 January 2016 | 890,000,000 | 2020 |

| Quizno’s | 7 January 2016 | 45,000,000 | 2025 |

| Denny’s | 14 January 2016 | 400,000,000 | 2026 |

| Mondelez | 16 January 2016 | 68,000,000 | 2020 |

| California Pizza Kitchen | 20 January 2016 | 3,000,000 | 2022 |

| Taco John’s | 20 January 2016 | 8,000,000 | 2025 |

| Target | 20 January 2016 | 1,590,000,000 | 2025 |

| P.F. Chang’s/Pei Wei | 23 January 2016 | 14,000,000 | 2025 |

| Schwan Food Co | 29 January 2016 | 37,000,000 | 2020 |

| White Castle | 29 January 2016 | 12,000,000 | 2025 |

| Sonic | 1 February 2016 | 155,000,000 | 2025 |

| Starwood Hotels | 1 February 2016 | 5,800,000 | 2020 |

| BJ’s | 9 February 2016 | 294,000,000 | 2022 |

| Trader Joe’s | 12 February 2016 | 638,400,000 | 2025 |

| Cracker Barrel | 15 February 2016 | 220,000,000 | 2026 |

| Applebee’s | 18 February 2016 | 4,000,000 | 2025 |

| CVS Health | 18 February 2016 | 71,100,000 | 2025 |

| Golden Corral | 18 February 2016 | 20,000,000 | 2026 |

| IHOP | 18 February 2016 | 214,000,000 | 2025 |

| Black Bear Diner | 19 February 2016 | 20,000,000 | 2025 |

| Bloomin’ Brands | 22 February 2016 | 1,300,000 | 2025 |

| Ahold | 23 February 2016 | 1,085,000,000 | 2022 |

| Krystal Burger | 23 February 2016 | 11,000,000 | 2026 |

| Albertsons | 1 March 2016 | 3,073,000,000 | 2025 |

| Kraft Heinz | 1 March 2016 | 313,000,000 | 2025 |

| WAWA | 1 March 2016 | 69,100,000 | 2020 |

| Delhaize America | 2 March 2016 | 1,757,000,000 | 2025 |

| Kroger | 4 March 2016 | 3,942,000,000 | 2025 |

| Bob Evans | 4 March 2016 | 100,000,000 | 2025 |

| The Fresh Market | 8 March 2016 | 236,600,000 | 2025 |

| Chick-fil-A | 9 March 2016 | 57,000,000 | 2026 |

| Aldi | 10 March 2016 | 1,260,000,000 | 2025 |

| Schnuck’s | 16 March 2016 | 144,200,000 | 2025 |

| Sprouts Market | 22 March 2016 | 324,800,000 | 2022 |

| Basha’s | 23 March 2016 | 151,200,000 | 2017 |

| Shoney’s | 23 March 2016 | 36,000,000 | 2025 |

| Raley’s | 24 March 2016 | 170,800,000 | 2020 |

| PepsiCo (Quaker) | 28 March 2016 | 10,000,000 | 2020 |

| Super Value | 29 March 2016 | 670,000,000 | 2025 |

| Weis Markets | 29 March 2016 | 232,400,000 | 2026 |

| Darden Restaurants, Inc. | 30 March 2016 | 10,000,000 | 2018 |

| Stater Bros. | 30 March 2016 | 236,600,000 | 2025 |

| Walgreens | 30 March 2016 | 76,500,000 | 2025 |

| Meijer | 1 April 2016 | 313,600,000 | 2025 |

| Lowes Food Stores | 2 April 2016 | 131,600,000 | 2025 |

| Smart & Final, Inc. | 2 April 2016 | 365,400,000 | 2025 |

| Ingles Markets | 4 April 2016 | 282,800,000 | 2025 |

| Krispy Kreme | 4 April 2016 | 620,000,000 | 2026 |

| Save Mart Supermarkets | 4 April 2016 | 303,800,000 | 2025 |

| Snyders-Lance | 4 April 2016 | 100,000,000 | 2025 |

| Walmart | 5 April 2016 | 11,500,000,000 | 2025 |

| Fairway Foods | 5 April 2016 | 21,000,000 | 2025 |

| King Kullen | 7 April 2016 | 51,800,000 | 2025 |

| Gelson’s Markets | 8 April 2016 | 36,400,000 | 2020 |

| Giant Eagle | 8 April 2016 | 294,000,000 | 2025 |

| Boyer’s Food Market | 9 April 2016 | 25,200,000 | 2026 |

| Brookshire Grocery Co. | 11 April 2016 | 210,000,000 | 2025 |

| SpartanNash | 11 April 2016 | 224,000,000 | 2025 |

| LeBrea Bakery | 12 April 2016 | 2,500,000 | 2016 |

| Vallarta Supermarkets | 13 April 2016 | 65,800,000 | 2025 |

| Southeastern (Winn-Dixie) | 15 April 2016 | 1,068,200,000 | 2025 |

| Tops Markets | 16 April 2016 | 229,600,000 | 2025 |

| Walt Disney | 16 April 2016 | 57,600,000 | 2016 |

| H-E-B | 18 April 2016 | 429,800,000 | 2025 |

| Wegman’s | 19 April 2016 | 126,000,000 | 2025 |

| Wakefern (ShopRite) | 22 April 2016 | 490,700,000 | 2025 |

| C&S Wholesale Grocers | 25 April 2016 | 427,000,000 | 2025 |

| Woodman’s Market | 26 April 2016 | 22,400,000 | 2025 |

| Dollar Tree/Family Dollar | 28 April 2016 | 250,000,000 | 2025 |

| 7-Eleven | 3 May 2016 | 118,500,000 | 2025 |

| Allegiance Retail (Foodtown) | 3 May 2016 | 119,000,000 | 2022 |

| Dollar General | 5 May 2016 | 320,000,000 | 2025 |

| Rite Aid | 6 May 2016 | 42,800,000 | 2025 |

| Heinen’s | 9 May 2016 | 30,800,000 | 2020 |

| Price Chopper/Market 32 | 9 May 2016 | 189,000,000 | 2025 |

| Carl’s Jr/Hardee’s | 10 May 2016 | 59,000,000 | 2025 |

| Dairy Queen/Orange Julius | 16 May 2016 | 40,000,000 | 2025 |

| Superior Grocers | 16 May 2016 | 63,000,000 | 2025 |

| Bojangles | 26 May 2016 | 92,000,000 | 2025 |

| Northgate Gonzalez | 27 May 2016 | 56,000,000 | 2025 |

| Grocery Outlet | 1 June 2016 | 210,000,000 | 2025 |

| US Foods | 1 June 2016 | 1,115,000,000 | 2026 |

| Dierberg’s | 2 June 2016 | 35,000,000 | 2025 |

| Associated Food Stores | 10 June 2016 | 594,600,000 | 2025 |

| CraftWorks Restaurants | 15 June 2016 | 2,500,000 | 2022 |

| Jerry’s Enterprises | 20 June 2016 | 36,400,000 | 2025 |

| Sysco | 20 June 2016 | 1,274,000,000 | 2026 |

| IGA, Inc. | 21 June 2016 | 870,000,000 | 2025 |

| Rouses Markets | 26 June 2016 | 61,600,000 | 2025 |

| Foodland Super Market | 29 June 2016 | 53,200,000 | 2025 |

| Reasor’s | 29 June 2016 | 26,600,000 | 2025 |

| BiRite Foodservice | 1 July 2016 | 13,000,000 | 2026 |

| Niemann Foods | 1 July 2016 | 61,600,000 | 2025 |

| Martin’s Super Markets | 8 July 2016 | 30,800,000 | 2025 |

| Harmon’s | 11 July 2016 | 22,400,000 | 2020 |

| Festival Foods (WI) | 15 July 2016 | 33,600,000 | 2025 |

| Publix Super Markets | 15 July 2016 | 1,579,200,000 | 2026 |

| Homeland Stores | 20 July 2016 | 84,000,000 | 2025 |

| Papa John’s | 20 July 2016 | 39,000,000 | 2016 |

| Mi Pueblo Food Center | 22 July 2016 | 26,600,000 | 2025 |

| Sedano’s | 22 July 2016 | 47,600,000 | 2026 |

| Casey’s General Stores | 26 July 2016 | 80,300,000 | 2025 |

| Barilla America, Inc. | 31 July 2016 | 38,000,000 | 2020 |

| Buehler Food Markets | 2 August 2016 | 21,000,000 | 2025 |

| Focus Brands | 5 August 2016 | 134,000,000 | 2026 |

| Key Food Stores | 8 August 2016 | 280,000,000 | 2025 |

| Compass Group | 15 September 2016 | 377,600,000 | 2019 |

| PAQ, Inc. (Food 4 Less) | 12 October 2016 | 58,800,000 | 2025 |

References

- Singer, P. Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congress. Office of Technology Assessment. Alternatives to Animal Use in Research, Testing, and Education; U.S. Congress. Office of Technology Assessment: Washington, DC, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Livestock Slaughter Annual Summary: 1982; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Statistical Reporting Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Quick Stats; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Council Directive 91/630/EEC of 19 November 1991 Laying Down Minimum Standards for the Protection of Pigs; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Commission Decision of 24 February 1997 Amending the Annex to Directive 91/629/EEC Laying Down Minimum Standards for the Protection of Calves; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Council Directive 1999/74/EC of 19 July 1999 Laying Down Minimum Standards for the Protection of Laying Hens; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, M.C. The European Union ban on conventional cages for laying hens: History and prospects. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2003, 6, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C. Cattle Behaviour and Welfare, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, A.N. Animal well-being: Key philosophical, ethical, political, and public issues affecting food animal agriculture. In Food Animal Well-Being; United States Department of Agriculture and Purdue University: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1993; pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- United States Congress. Veal Calf Protection Act: Joint Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry and the Subcommittee on Department Operations, Research, and Foreign Agriculture of the Committee on Agriculture, House of Representatives; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, A.N.; Rosen, B. Progress in animal legislation: Measurement and assessment. In The State of the Animals III; Salem, D.J., Rowan, A.N., Eds.; Humane Society Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Centner, T.J. Limitations on the confinement of food animals in the United States. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2010, 23, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. Animal Machines: The New Factory Farming Industry; Vincent Stuart Ltd.: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Broom, D. A History of Animal Welfare Science. Acta Biotheor. 2011, 59, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambell, F.W.R. Report of the Technical Committee to Enquire into the Welfare of Animals Kept Under Intensive Livestock Husbandry Systems; Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Scotland and the Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food by Command of Her Majesty; Her Majesty’s Stationary Office: London, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, L.J. Healthy and happy: Animal welfare as an integral part of sustainable agriculture. Ambio 2005, 34, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Protection of Animals Kept for Farming Purposes; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, Belgium, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, I.J. Behavior and behavioral needs. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 1766–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, P.; Toates, F.M. Who needs ‘behavioural needs’? Motivational aspects of the needs of animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 37, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, J.N.; Broom, D.M. Effects of dry sow housing conditions on muscle weight and bone strength. Anim. Sci. 1996, 62, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, E.L.; McMunn, K.A.; Rosenstein, D.S.; Stroshine, R.L.; Nielsen, B.D.; Richert, B.T.; Marchant-Forde, J.N.; Lay, D.C., Jr. Exercising stall-housed gestating gilts: Effects on lameness, the musculo-skeletal system, production, and behavior. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 3166–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arellano, P.E.; Pijoan, C.; Jacobson, L.D.; Algers, B. Stereotyped behaviour, social interactions and suckling pattern of pigs housed in groups or in single crates. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1992, 35, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieuille-Thomas, C.; Pape, G.L.; Signoret, J.P. Stereotypies in pregnant sows: Indications of influence of the housing system on the patterns expressed by the animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1995, 44, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, E.M.C.; Lawrence, A.B.; Illius, A.W. Influences of feeding level and physical restriction on development of stereotypies in sows. Anim. Behav. 1991, 42, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolba, A.; Wood-Gush, D.G.M. The behaviour of pigs in a semi-natural environment. Anim. Prod. 1989, 48, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, I.A.S.; Keeling, L.J. Why in earth? Dustbathing behaviour in jungle and domestic fowl reviewed from a Tinbergian and animal welfare perspective. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 93, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, I.A.S.; Keeling, L.J. Night-time roosting in laying hens and the effect of thwarting access to perches. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 68, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, F.; Appleby, M.C.; Hughes, B.O. Effects of nest quality and other cues for exploration on pre-laying behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 48, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Van Praag, H.; Kempermann, G.; Gage, F.H. Neural consequences of environmental enrichment. Nat. Rev. 2000, 1, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M.H.; Presti, M.F.; Lewis, J.B.; Turner, C.A. The neurobiology of stereotypy I: Environmental complexity. In Stereotypic Animal Behaviour: Fundamentals and Applications to Welfare, 2nd ed.; Mason, G., Rushen, J., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2006; pp. 190–226. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Milk Cows and Production Final Estimates 2003–2007; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Hogs and Pigs: Number of Operations and Inventory; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service, Arizona Agricultural Statistics: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arizona Revised Statutes. Initiative, Referendum and Recall; Arizona Revised Statutes: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2005; Title 19, Section 19–114(A); Available online: http://law.justia.com/codes/arizona/2014/title-19/ (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Arizona Revised Statutes. Cruel and Inhumane Confinement of a Pig during Pregnancy or of a Calf Raised for Veal; Arizona Revised Statutes: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 1998; Title 13, Criminal Code, Chapter 29, Section 2910.07; Available online: https://www.animallaw.info/statute/az-initiatives-proposition-204-inhumane-confinement (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Smith, R. Veal group housing approved. Feedstuffs, 6 August 2007; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hormel Plans Phase-Out of Gestation Crates by 2017. Available online: http://www.nationalhogfarmer.com/animal-well-being/hormel-plans-phase-out-gestation-crates-2017 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Freese, B. Top 35 U.S. Pork Powerhouses® 2016; Meredith Agrimedia: Des Moines, IA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Evaluation of FSIS Management Controls over Pre-Slaughter Activities; Audit Report No. 24601-0007-KC; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Office of Inspector General Great Plains Region: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Continuing Problems in USDA’s Enforcement of the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act. Available online: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-111hhrg65127/html/CHRG-111hhrg65127.htm (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Letter to The Honorable Ed Schafer, Secretary, United States Department of Agriculture. RE: Humane Handling of Downed Animals at Slaughterhouses, Auctions, and Markets. 2 May 2008. Available online: www.humanesociety.org/assets/pdfs/farm/pacelle-to-usda-downers-05-02-08.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2017).

- Review of the Welfare of Animals in Agriculture. Available online: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-110hhrg39809/html/CHRG-110hhrg39809.htm (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Kucinich, D. Opening Statement. Hearing on Adequacy of the USDA Oversight of Federal Slaughter Plants; Domestic Policy Subcommittee, House Office Building: Washington, DC, USA, 17 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, R. Video reveals violations of laws, abuse of cows at slaughterhouse. The Washington Post, 30 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fiegel, E. Humane Society: Undercover Video Shows Alleged Abuse at Egg Farm; CNN: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kitroeff, N.; Mackey, R. Activists accuse Walmart of condoning torture of pigs by pork suppliers. The New York Times, 1 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe, E. Official blows whistle on food-safety agency. The Washington Post, 5 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, M. Punishing animal rights activists for animal abuse: Rapid reporting and the new wave of ag-gag laws. Columbia J. Law Soc. Probl. 2014–2015, 48, 337–371. [Google Scholar]

- Landfried, J. Bound & gagged: Potential first amendment challenges to ag-gag laws. Duke Environ. Law Policy Forum 2012, 23, 377–403. [Google Scholar]

- Liebmann, L. Fraud and first amendment protections of false speech: How United States v. Alvarez impacts constitutional challenges to ag-gag laws. Pace Environ. Law Rev. 2014, 31, 565–593. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, T. Hallmark/Westland: One year later. Meatingplace, February 2009; 10. [Google Scholar]

- Prohibition against Restrictive Confinement. Available online: https://www.oregonlaws.org/ors/600.150 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Confinement of Calves Raised for Veal and Pregnant Sows. Available online: https://www.animallaw.info/statute/co-farming-article-505-confinement-calves-raised-veal-and-pregnant-sows (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Putting Meat on the Table: Industrial Farm Animal Production in America. Available online: http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2008/04/29/putting-meat-on-the-table-industrial-farm-animal-production-in-america (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- United States Department of Agriculture. Chickens and Eggs 2007 Summary; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Egg Producers. United Egg Producers Animal Husbandry Guidelines for U.S. Egg Laying Flocks; United Egg Producers: Alpharetta, GA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Meadow, B.; Kannel, S.; Undem, T.; Crain, D. Arizona Farm Animal Confinement Issues, Survey Research Analysis; Prepared for the Humane Society of the United States; Lake Snell Perry Mermin Decision Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lake Research Partners. California: 800 Likely Voters in the 2008 Election; Prepared for the Humane Society of the United States; Lake Research Partners: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Farm Animal Cruelty. Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=HSC&division=20.&title=&part=&chapter=13.8.&article= (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Prop 2 Standards for Confining Farm Animals Initiative Statute. Available online: https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_2,_Standards_for_Confining_Farm_Animals_(2008) (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Nieves, E. Farm animal rights law would require more room to roam. The Mercury News, 28 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Californians for Humane Farms v. Schafer, No. C08-03843 MHP, 2008 Westlaw 4449583. Available online: https://www.animallaw.info/case/californians-humane-farms-v-schafer (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Bell, D. A review of recent publications on animal welfare issues for table egg laying hens. Available online: https://www.google.ch/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwiQrard__DTAhXkKcAKHR0UAuoQFgglMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fanimalsciencey.ucdavis.edu%2Favian%2FWelfareIssueslayingHens.pdf&usg=AFQjCNH5Ro9QZSAlN8AuHSbqtbrez57_Ig&cad=rja (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Processed Egg Products Antitrust Litigation, No. 08-md-2002, 2016 Westlaw 5539592. Available online: http://www.leagle.com/decision/In%20FDCO%2020160907D87/IN%20RE%20PROCESSED%20EGG%20PRODUCTS%20ANTITRUST%20LITIGATION (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Patrick, M.E.; Adcock, P.M.; Gomez, T.M.; Altekruse, S.F.; Holland, B.H.; Tauxe, R.V.; Swerdlow, D.L. Salmonella Enteritidis infections, United States, 1985–1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway, T.R.; Edrington, T.S.; Anderson, R.C.; Byrd, J.A.; Nisbet, D.J. Gastrointestinal microbial ecology and the safety of our food supply as related to Salmonella. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, E163–E172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority. Report of the Task Force on Zoonoses Data Collection on the Analysis of the baseline study on the prevalence of Salmonella in holdings of laying hen flocks of Gallus gallus. EFSA J. 2007, 97, 1–84. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Multistate Outbreak of Human Salmonella Enteritidis Infections Associated with Shell Eggs (Final Update). 2 December 2010. Available online: www.cdc.gov/salmonella/2010/shell-eggs-12-2-10.html (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- United States District Court. Avila, et al. v. Olivera Egg Ranch, LLC, 2011 Westlaw 12882109; United States District Court, Eastern District of California: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meadow, B.; Ulibarri, J. Post-Election Survey of 800 Californians Who Voted in the 2008 Election; Lake Research Partners: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- California Superior Court. J.S. West Milling Co., Inc. v. State of California, et al., No. 10-CECG-04225; California Superior Court: Fresno, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United States Court of Appeals. Cramer v. Harris, 591. Federal Appendix 634; United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- California Superior Court. Association of California Egg Farms v. State of California, et al., No. 12-CECG-03695; California Superior Court: Fresno, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shelled Eggs; California Health and Safety Code, Division 20. Miscellaneous Health and Safety Provisions. Chapter 14, Section 25996. Available online: http://codes.findlaw.com/ca/health-and-safety-code/hsc-sect-25996.html (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- United States Court of Appeals. Missouri ex rel. Koster v. Harris, Petition for Cert. filed No. 16-1015, 847 Federal Reporter 3d 646, 650; United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cruelty to Animals; Maine Revised Statutes: Title 7, Agriculture and Animals, Part 9, Animal Welfare, Chapter 739: Section 4011. Available online: http://legislature.maine.gov/statutes/7/title7sec4011.html (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Animal Industry Act; Michigan Compiled Laws. Chapter 287: Section 287.746. Available online: http://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(abtezdr0xncbzlfxmztnr0e4))/mileg.aspx?page=GetObject&objectname=mcl-act-466-of-1988 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- United States Department of Agriculture. Chickens and Eggs 2009 Summary; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ohio Department of Agriculture. 2009 Annual Report; Ohio Department of Agriculture: Reynoldsburg, OH, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.agri.ohio.gov/divs/Admin/Docs/AnnReports/ODA_Comm_AnnRpt_2009.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Ohio Livestock Care Standards Board; Ohio revised codes. Title 9. Agriculture Chapter 904: Sections 904.01–904.09. Available online: http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/904 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- 112th Congress, Second Session. H.R. 3798. To Provide for a Uniform National Standard for the Housing and Treatment of Egg-Laying Hens, and for Other Purposes. 23 January 2012. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/3798/text (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- 113th Congress, 1st Session. S. 820. To Provide for a Uniform National Standard for the Housing and Treatment of Egg-Laying Hens, and for Other Purposes. 25 April 2013. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/820/text?format=txt (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- United States Department of Agriculture. Cage-Free Statistics from USDA; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainability Goes Mainstream: Insights into Investor Views. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/us/en/pwc-investor-resource-institute/publications/assets/pwc-sustainability-goes-mainstream-investor-views.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Summary of the Judgement (Read in Open Court) before The Hon. Mr Justice Bell. High Court of Justice, Queens Bench Division: London, Thursday, 19 June 1997. Available online: https://www.big-lies.org/general/ek2-mclibel-judgment-summary.html (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Armstrong, S. Bunfight. The Guardian. 13 September 1999. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/media/1999/sep/13/marketingandpr.mondaymediasection (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Grandin, T. Effect of animal welfare audits of slaughter plants by a major fast food company on cattle handling and stunning practices. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 216, 848–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandin, T. The McDonald’s Effect. Beef Magazine. 1 February 2001. Available online: http://www.beefmagazine.com/mag/beef_mcdonalds_effect (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Pacelle, W. The Humane Economy; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strom, S. McDonald’s set to phase out suppliers’ use of sow stalls. The New York Times. 13 February 2012. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/14/business/mcdonalds-vows-to-help-end-use-of-sow-crates.html (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Murphy, R. Smithfield Foods moves to end use of breeding crates on company farms. Daily Press. 7 January 2015. Available online: http://www.dailypress.com/news/isle-of-wight-county/dp-nws-smithfield-gestation-crates-progress-20150107-story.html (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Barclay, E. Smithfield prods its pork suppliers to dump pig crates. National Public Radio. 7 January 2014. Available online: http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/01/07/260439063/smithfield-prods-its-pork-suppliers-to-dump-pig-crates (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Press Releases. Smithfield Foods Nears 2017 Goal for Conversion to Group Housing Systems for Pregnant Sows. Smithfield, VA. 4 January 2017. Available online: www.smithfieldfoods.com/newsroom/press-releases-and-news/smithfield-foods-nears-2017-goal-for-conversion-to-group-housing-systems-for-pregnant-sows (accessed on 9 April 2017).

- Smithfield 2015 Sustainability & Financial Report. Housing of Pregnant Sows. Available online: www.smithfieldfoods.com/integrated-report/2015/animal-care/housing-of-pregnant-sows (accessed on 9 April 2017).

- Hormel Foods. Animal Welfare. Available online: www.hormelfoods.com/About/CorporateResponsibility/Animal-Welfare (accessed on 9 April 2017).

- Cargill. Corporate Responsibility Report; Cargill: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clemens Food Group Commitment to Animal Care. Available online: www.cfgsustainability.com/animal-welfare/at-the-farm.aspx (accessed on 9 April 2017).

- Robert Ruth; Clemens Food Group. Personal communication, 2016.

- Tyson Fresh Meats, Inc. Letter to Suppliers, dated 8 January 2014. Available online: https://www.google.ch/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwjg3ae4gPHTAhWHDcAKHQ6zC48QFggiMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.tysonfoods.com%2F~%2Fmedia%2FCorporate%2FMedia%2FPosition%2520Statements%2FPork%2520Supplier%2520Letter%25201-8-14.ashx&usg=AFQjCNGA92Nq8T_TqDx-ypEKTv6LPvXH2g&cad=rja (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Tyson Foods Inc. Position Statement on Sow Housing Dated 23 March. Available online: www.tysonfoods.com/media/position-statements/sow-housing (accessed on 6 October 2016).

- Top 25 U.S. Pork Powerhouses® 2015. Available online: http://www.porelia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2015PorkPowerhousesChartREV.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- McCrea, R.C. The Humane Movement: A Descriptive Survey; Henry Bergh Foundation, Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), Office of Research Infrastructure Programs. NIH Plan to Retire All NIH-Owned and -Supported Chimpanzees. Available online: https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/orip/cm/chimpanzeeretirement (accessed on 9 April 2017).

- Cecil the Lion Killing Sparks Outrage around the World. CBS News. 29 July 2015. Available online: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/cecil-the-lion-killing-sparks-outrage-around-the-world/ (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Macdonald, D.W.; Jacobsen, K.S.; Burnham, D.; Johnson, P.J.; Loveridge, A.J. Cecil: A moment or a movement? Analysis of media coverage of the death of a lion, Panthera leo. Animals 2016, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A. American dentist who admitted killing Cecil the lion now hounded on social media. ABC News. 30 July 2015. Available online: http://abcnews.go.com/International/american-dentist-admitted-killing-cecil-lion-now-hounded/story?id=32757906 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- McKendree, M.G.S.; Croney, C.C.; Widmar, N.J.O. Effects of demographic factors and information sources on United States consumer perceptions of animal welfare. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 3161–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riffkin, R. In U.S., more say animals should have same rights as people. Gallup Social Issues. 18 May 2015. Available online: http://www.gallup.com/poll/183275/say-animals-rights-people.aspx (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Wells, J. How California egg rules could affect everyone’s breakfast. NBC News. 2 January 2015. Available online: http://www.nbcnews.com/business/consumer/how-california-egg-rules-could-affect-everyones-breakfast-n278531 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Jargon, J.; Beilfuss, L. McDonald’s continues with image shift with move to cage-free eggs in North America. The Wall Street Journal. 9 September 2015. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/mcdonalds-to-source-cage-free-eggs-in-u-s-canada-1441798121 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Brulliard, K. How eggs became a victory for the animal welfare movement. The Washington Post. 6 August 2016. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/animalia/wp/2016/08/06/how-eggs-became-a-victory-for-the-animal-welfare-movement-if-not-necessarily-for-hens/?utm_term=.0ea04229cb03 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Jolley, C. Tipping point reached on cage-free. Feedstuffs. 28 February 2016. Available online: http://feedstuffsfoodlink.com/blogs-tipping-point-reached-cage-free-10695 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Walmart Press Release. Commitment Represents Company’s Continued Focus on Advancing Animal Welfare; Walmart Press: Bentonville, AR, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles, D. Eggs that clear the cages, but maybe not the conscience. The New York Times. 16 July 2016. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/17/business/eggs-that-clear-the-cages-but-maybe-not-the-conscience.html (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Malcolm, H. Walmart’s cage-free egg vow could cut prices, aid hens. USA Today. 7 April 2016. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2016/04/06/cage-free-eggs-expected-to-get-cheaper/82702828/ (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Colman, Z. The fight for cage-free eggs. The Atlantic. 16 April 2016. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/04/a-referendum-on-animal-rights/478482/ (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Barclay, E. The year in eggs: Everyone’s going cage-free, except supermarkets. National Public Radio. 30 December 2015. Available online: http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/12/30/461483821/the-year-in-eggs-everyones-going-cage-free-except-supermarkets (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Charles, D. Most U.S. egg producers are now choosing cage-free houses. National Public Radio. 15 January 2016. Available online: http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/01/15/463190984/most-new-hen-houses-are-now-cage-free (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Charles, D. What the rise of cage-free eggs means for chickens. National Public Radio. 27 June 2013. Available online: http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2013/06/27/195639341/what-the-rise-of-cage-free-eggs-means-for-chickens (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Kowitt, B. Inside McDonald’s bold decision to go cage-free. Fortune. 18 August 2016. Available online: http://fortune.com/mcdonalds-cage-free/ (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Lempert, P. Shift to cage-free eggs is likely to disappoint. Forbes. 8 May 2016. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/phillempert/2016/05/08/shift-to-cage-free-eggs-is-likely-to-disappoint/#3e6846b85fd3 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Chaussee, J. The insanely complicated logistics of cage-free egss for all. Wired. 25 January 2016. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2016/01/the-insanely-complicated-logistics-of-cage-free-eggs-for-all/ (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- United States Department of Agriculture. Chickens and Eggs 2016 Summary; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Statistics Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/current/ChickEgg/ChickEgg-02-27-2017.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- An Act to Prevent Cruelty to Farm Animals. Available online: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2016/Chapter333 (accessed on 4 October 2016).

| Company | Pledge Date | Number of Sows | Transition Time-Line | Time in Individual Crates during and Following Breeding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company Owned Farms | Contracted Producers | ||||

| Smithfield | 2007 | 880,000 | 2017 | 2022 | Individual stalls until confirmed pregnant |

| Hormel | 2012 | 52,000 | 2018 | Not included | Not available |

| Cargill | 2014 | 175,000 * | 2015 | 2017 | 28–42 days |

| Clemens | 2014 | 55,100 | 2017 | 2022 | 7–10 days on company owned farms; up to 42 days in contract production |

| Tyson | 2014 | 62,500 | Does not own | 32% group housing as of March 2016 | Not available |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shields, S.; Shapiro, P.; Rowan, A. A Decade of Progress toward Ending the Intensive Confinement of Farm Animals in the United States. Animals 2017, 7, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7050040

Shields S, Shapiro P, Rowan A. A Decade of Progress toward Ending the Intensive Confinement of Farm Animals in the United States. Animals. 2017; 7(5):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7050040

Chicago/Turabian StyleShields, Sara, Paul Shapiro, and Andrew Rowan. 2017. "A Decade of Progress toward Ending the Intensive Confinement of Farm Animals in the United States" Animals 7, no. 5: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7050040