Designing Effective Interactions for Concordance around End-of-Life Care Decisions: Lessons from Hospice Admission Nurses

Abstract

:1. Background

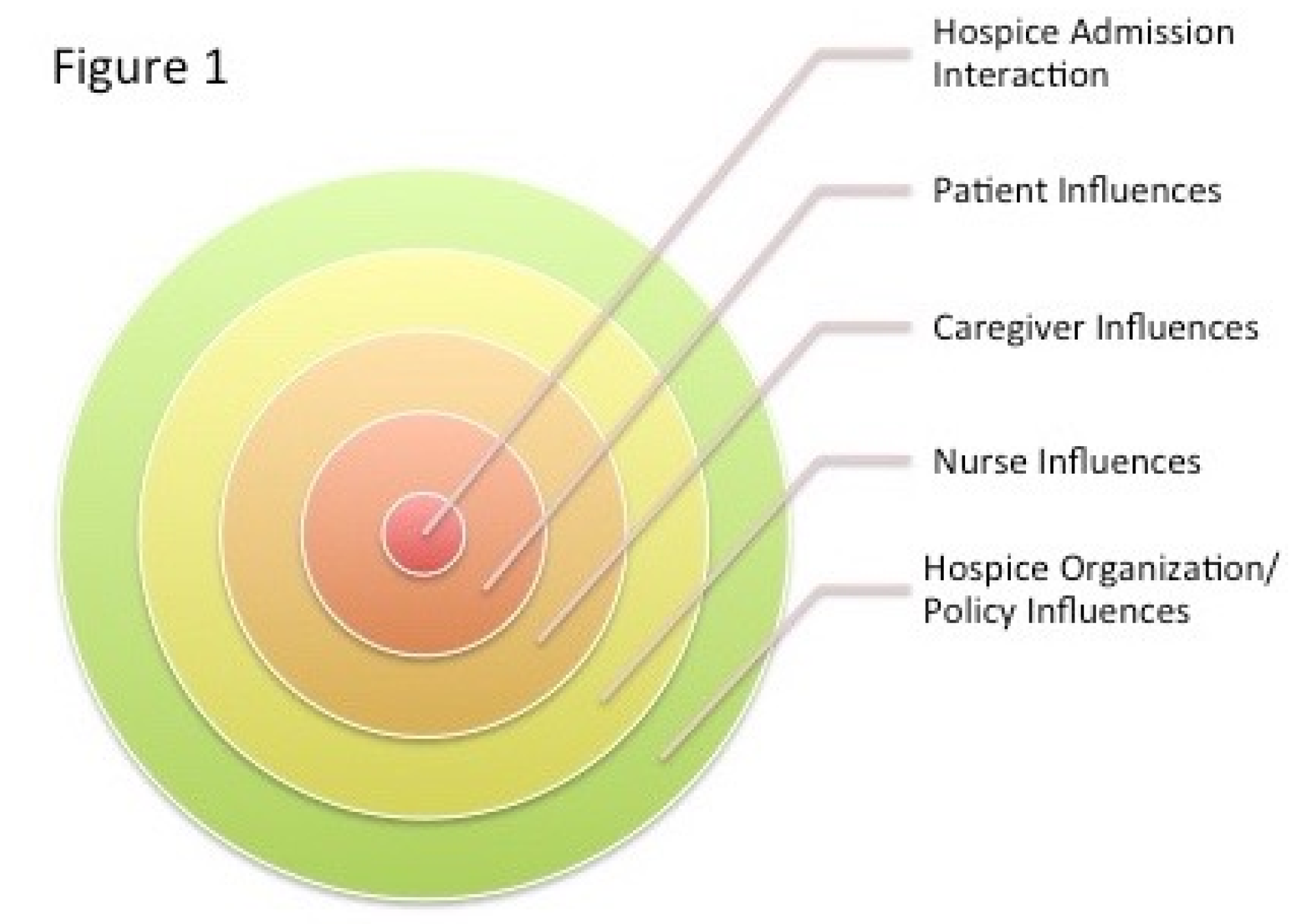

2. Analyzing Hospice Admissions from an Ecological Perspective

3. Research Setting and Sample

4. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Ethical Considerations

6. Real Case Exemplar: “I Don’t Want to Go Back and See Her, Just Tell Me If It’s Time for My Mom to Start Hospice”

6.1. Background and Context to the Interaction

6.2. Notes from Hospice Organization to the Admissions Nurse

6.3. The Patient

6.4. Interaction with Emily the Family Caregiver (Daughter)

- J:

- “Before I give you a bunch of information, can you tell me your understanding of hospice?”

- E:

- “I understand it as two levels of care. Palliative being less hands-on, and hospice being more involved.”

- J:

- “I saw your mom very briefly earlier today and she is doing well. She got up by herself and walked about the room. She’s continent.”

- E:

- “She’s continent? She has been in a diaper every time I have seen her.”

- J:

- “Sometimes around here they put diapers on almost like a security blanket so the patients can be relaxed if they have an accident or can’t get up quickly enough to the restroom. We can go see her after we finish our conversation.”

- E:

- “I don’t want to go back.”

- J:

- “What are your goals today?”

- E:

- “We want an honest assessment of where she is to determine if we should enroll in palliative or hospice care. You are the experts. We are leaning more towards palliative care, but we just don’t know. Is she eligible for hospice? Would her doctor support that decision?”

- J:

- “Yes, he said he would support that decision.”

- E:

- “I’m confused—I thought he didn’t feel she was appropriate?”’

- J:

- “Initially, Dr. Hanks said he didn’t think she was appropriate for hospice, but in the chart from November it states he would support the decision to enroll in hospice if we felt she met criteria, which I feel she does. After seeing your mother, I think she can benefit from palliative or hospice care, and I have information and paperwork on both options today. But this decision is ultimately for you and your family to make. Do you know what she wants?”

- E:

- “No, I mean she can’t communicate.”

- J:

- “Did you talk with her before about what she would want?”

- E:

- “Not really. But I think she’s ready for palliative care and until the doctors feel absolutely certain she is ready for hospice, we will go from there. Is that reasonable?”

- J:

- “Yes, absolutely.”

- E:

- “Can you re-evaluate her in 90 days? It’s risky, I know, since she could go downhill quickly and maybe need more help.”

- J:

- “It’s a very difficult decision, and we want to help you in whatever way we can. We can fill out both paperwork, and you can think more about it and let us know within a few days.”

- E:

- “Do you think she is ready for hospice?”

- J:

- “I think she is, but the decision to enroll is really up to you. She is eligible and would certainly have more eyes on her with a larger care team.”

- E:

- “Would she have more interaction and would your team interact with the team here okay?”

- J:

- “Yes, she would have more frequent visits on our hospice program, as our palliative team serves more in a consultative capacity. But know that both programs provide an extra layer of support to our patients. Hospice also works hard to provide support to you as her family member…we know this is a challenging time.”

- E:

- “I don’t know what to do. This is really hard and you’re not giving me any guidance!” (Emily gives her first brief smile.)

- J:

- “We just want you to be prepared as possible should things get worse, and we want to be able to best support you all. So often patients and families wait until they are close to dying before enrolling in these services, whereas signing up earlier could really benefit not only your mom, but you and your siblings as well. If I could make a recommendation, I would encourage you to sign your mom up for palliative care today and then we can move her onto hospice services when you feel more comfortable with that transition. If you change your mind, just give us a call; these decisions are not set in stone. Your palliative team will also help you understand when the time is right for a transition to hospice.”

- E:

- “You know, my father died 10 years ago. My mom insisted he get cancer treatment until the day he died while living at home. It was a Saturday and my mother wanted us to haul him to the hospital for another treatment. He was so sick and so weak. And my family and I finally intervened and told my mother no. He died that following Monday.” (pauses) “I want hospice. Let’s go directly to hospice. I don’t want to have her be on hospice for 4–5 years, but I also don’t want to ignore something she might really need and benefit from. This is so hard.”

- E:

- “I want her as comfortable as possible and free of pain, with an extra set of eyes.” (Emily’s eyes fill with tears. James pulls out the paperwork.)

- J:

- “Just remember that no matter what you decide, you can always change your mind at any point.”

- E:

- “You can re-evaluate her at 90 days, right? This is so hard.”

- J:

- “Yes, we can, and I will put that in the notes.”

- J:

- “Your birthday is coming up!”

- E:

- “And so is my mom’s.”

- J:

- “Are you having a party for her?”

- E:

- “No, actually. I will be in Chicago.

- E:

- “Hi, Katie, how is she doing?”

- E:

- “Is she still on oxygen?”

- K:

- “No, just as needed.”

- E:

- “I left some clothes for her at the front. Can you take them back to her?”

- K:

- “Sure.”

- E:

- “Thank you, and I will talk with you soon, ok? I would like to know more about that bereavement program for children you spoke of because my mother’s granddaughter has a lot of emotional issues and would benefit from that support. Can you put that in the notes?”

- J:

- “You got it. Thanks for coming, Emily.”

- First, participants play multiple roles: Hospice nurses are asked to play many different roles at any given moment (e.g., medical professional, social worker, therapist, end-of-life-care expert, facilitator, advisor, educator, etc.). It is important to have these roles defined and understood from the outset and re-confirmed throughout the interaction.

- Second, participant goals vary: Patient and caregiver goals can vary, change, and evolve visit-to-visit. Clarifying the goal of the interaction enhances the likelihood of establishing trust at the beginning of the encounter and reaching concordance.

- Third, understanding intersection(s) is key to adaptation: Understanding that roles and goals may come into opposition, but finding intersections where concordance, or points of commonality between people’s purposes, concerns, and circumstances exists and remaining focused and adaptive leads to better shared decision-making. Finding intersections quickly and returning to them frequently helps discern between what patients/caregivers want, what they do not want, and what role the nurse must play to help the patient and family achieve those goals in light of their unique circumstances.

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Casarett, D.J.; Crowley, R.; Stevenson, C.; Xie, S.; Teno, J. Making difficult decisions about hospice enrollment: What do patients and families want to know? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casarett, D.J.; Crowley, R.; Hirschman, K.B. How should clinicians describe hospice to patients and families? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 1923–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candy, B.; Holman, A.; Leurent, B.; Davis, S.; Jones, L. Hospice care delivered at home, in nursing homes and in dedicated hospice facilities: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 48, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.B.; Slaninka, S.C. Barriers to accessing hospice services before a late terminal stage. Death Stud. 1999, 23, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Myers, G.E. Can illness narratives contribute to the delay of hospice admission? Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2002, 19, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E.M.; Thompson, S. Understanding enrollment conversations: The role of the hospice admissions representative. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2006, 23, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of Inspector General Report. Available online: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-10-00492.asp (accessed on 1 December 2016).

- Street, R.L.; O’Malley, K.J.; Cooper, L.A.; Haidet, P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: Personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinker, M. Personal paper: Writing prescriptions is easy, but to come to an understanding of people is hard. BMJ 1997, 314, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, R.L. Communication in medical encounters: An ecological perspective. In Handbook of Health Communication; Thompson, T., Dorsey, A., Parrott, R., Miller, K., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.C. The four seasons of ethnography: A creation-centered ontology for ethnography. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2000, 24, 623–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, L. Communicating in the Clinic: Negotiating Frontstage and Backstage Teamwork; Hampton Press: Cresskill, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Broadfoot, K.J. “She’s come undone!”: Engaging scholarship and viral research. In Engaging Communication, Transforming Organizations: Scholarship of Engagement in Action; Simpson, J.L., Shockley-Zalabak, P., Eds.; Hampton Press: Cresskill, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, K. Blood, vomit, and communication: The days and nights of an intern on call. Health Commun. 1999, 11, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, E. Lessons we learned: Stories of volunteer-patient communication in hospice. J. Aging Identity 2002, 7, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, E.; Murphy, K.; Wears, R.; Schenkel, S.; Perry, S.; Vanderhoef, M. Communication in emergency medicine: Implications for patient safety. Commun. Monogr. 2005, 72, 390–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcoff, L. The problem of speaking for others. Cult. Crit. 1991–1992, 20, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindlof, T.R.; Taylor, B.C. Qualitative Communication Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, R.L.; Makoul, G.; Arora, N.K.; Epstein, R.M. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 84, 795–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupton, D. Toward the development of critical health communication praxis. Health Commun. 1994, 6, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauser, K.E.; Barosso, J. Using qualitative methods to answer key questions in palliative care. J. Palliat. Med. 2009, 12, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Candrian, C.; Tate, C.; Broadfoot, K.; Tsantes, A.; Matlock, D.; Kutner, J. Designing Effective Interactions for Concordance around End-of-Life Care Decisions: Lessons from Hospice Admission Nurses. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020022

Candrian C, Tate C, Broadfoot K, Tsantes A, Matlock D, Kutner J. Designing Effective Interactions for Concordance around End-of-Life Care Decisions: Lessons from Hospice Admission Nurses. Behavioral Sciences. 2017; 7(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleCandrian, Carey, Channing Tate, Kirsten Broadfoot, Alexandra Tsantes, Daniel Matlock, and Jean Kutner. 2017. "Designing Effective Interactions for Concordance around End-of-Life Care Decisions: Lessons from Hospice Admission Nurses" Behavioral Sciences 7, no. 2: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7020022