Embodied Cognition and the Direct Induction of Affect as a Compliment to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Limitations of Cognitive Therapies

1.2. Different Methodologies

1.3. Non-Responders to CBT

1.4. Sandwich Model of CBT

1.5. Limitations of the Sandwich Model

1.6. Affect Experience as an Important Treatment Outcome Variable

2. Integration of CBT with Emotionally Focused Treatment (EFT) Approaches

3. The Embodied Model of Cognition and Emotion

Review of the Research in Support of Embodiment Techniques in Psychotherapy

4. A unifying Perspective for Clinical Psychology: Integration of Bottom-Up and Top-Down Modes

- Seek lingual expression for an experience, provide interpretation and re-interpretation of experiences.

- Identify and examine belief sets, compare, relativize and communicate what is experienced.

- Elaborate problem solutions, targets, plans and interim steps and the timing of these.

- Have a time frame perspective covering past experiences into future experiences.

- Focus is placed on sensory and physical perceptions and impulses, movements of the whole body and parts of the body in space.

- Clients focus their attention and observe their body processes to gain access to the roots of their emotional experiences, to their automatic impulses and pre-lingual processes.

- Sensory motor input is induced by probing, tensing, moving, conscious breathing in order to place automated processes and categorizations into conscious awareness.

- Time perspective focuses on the ‘here and now,’ thus providing a chance of escaping the ‘memory trance,’ resisting automatisms and trying out alternatives.

4.1. Embodiment Techniques Defined

4.2. Integrated Psychotherapy Approach: A Type of Embodied CBT

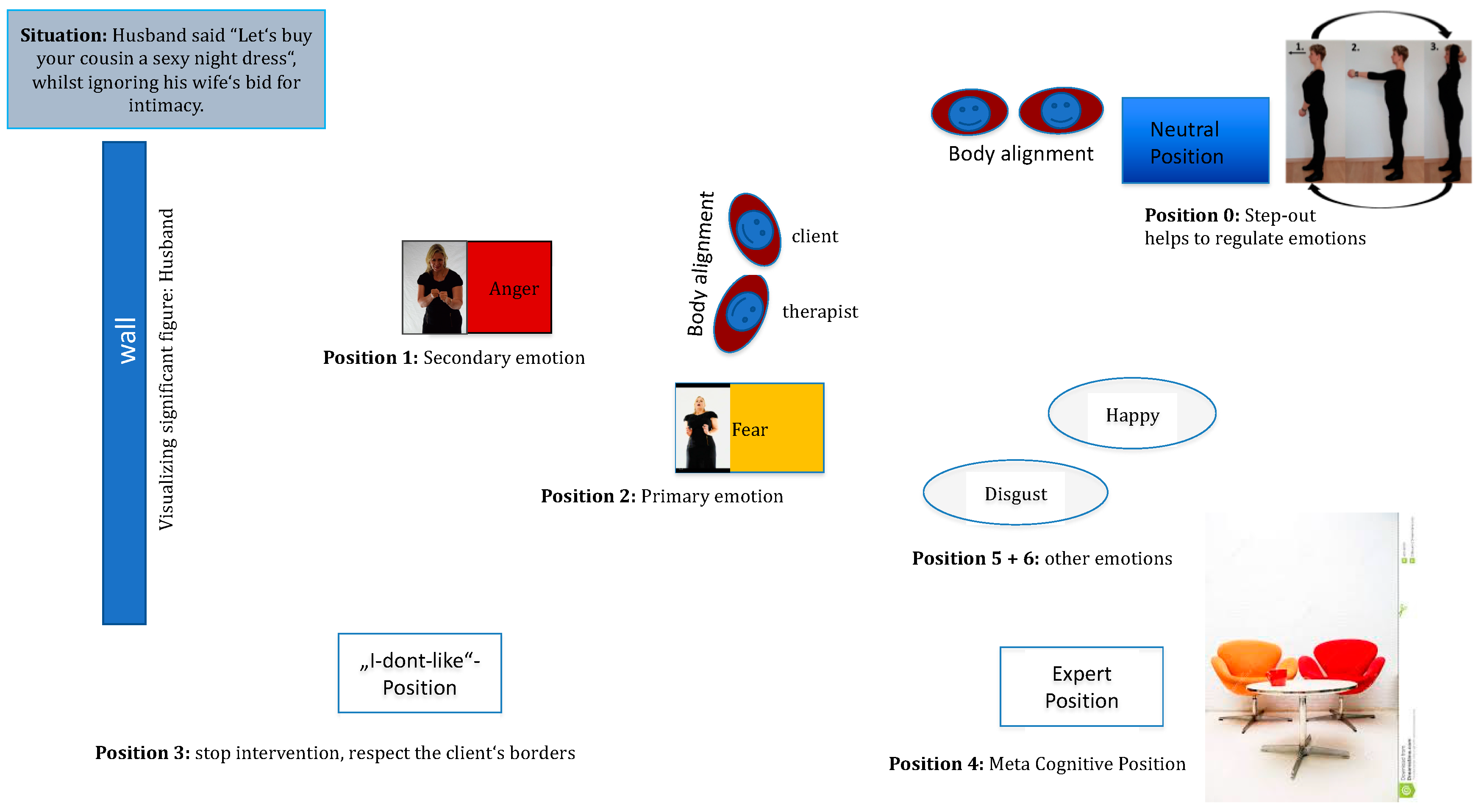

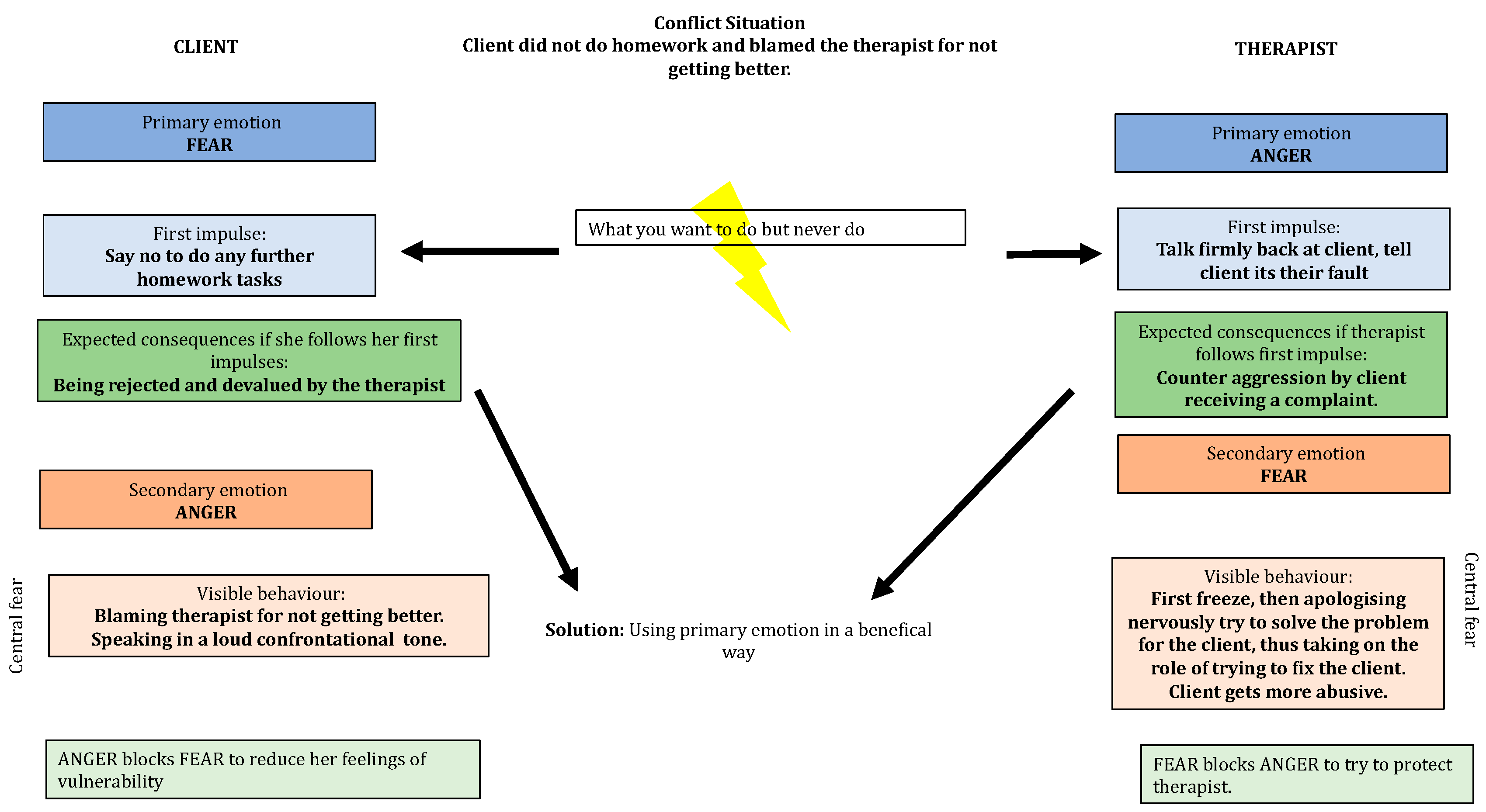

4.3. Method of the Emotional Field in the Switch Model

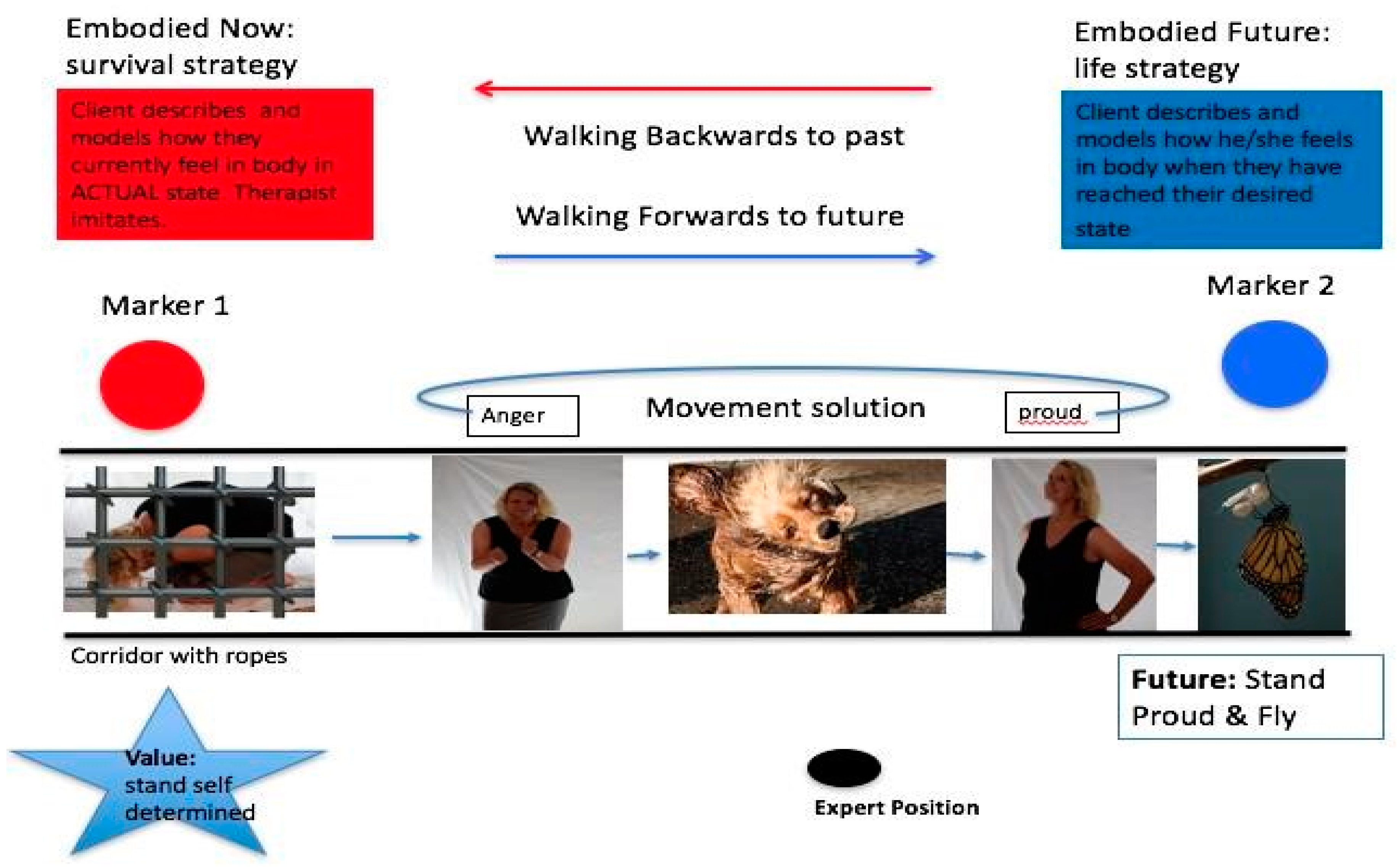

4.4. Resource Activation and Emotional Mastery: Moving to Solutions

4.5. Preliminary Support for the Switch Model of Embodied CBT

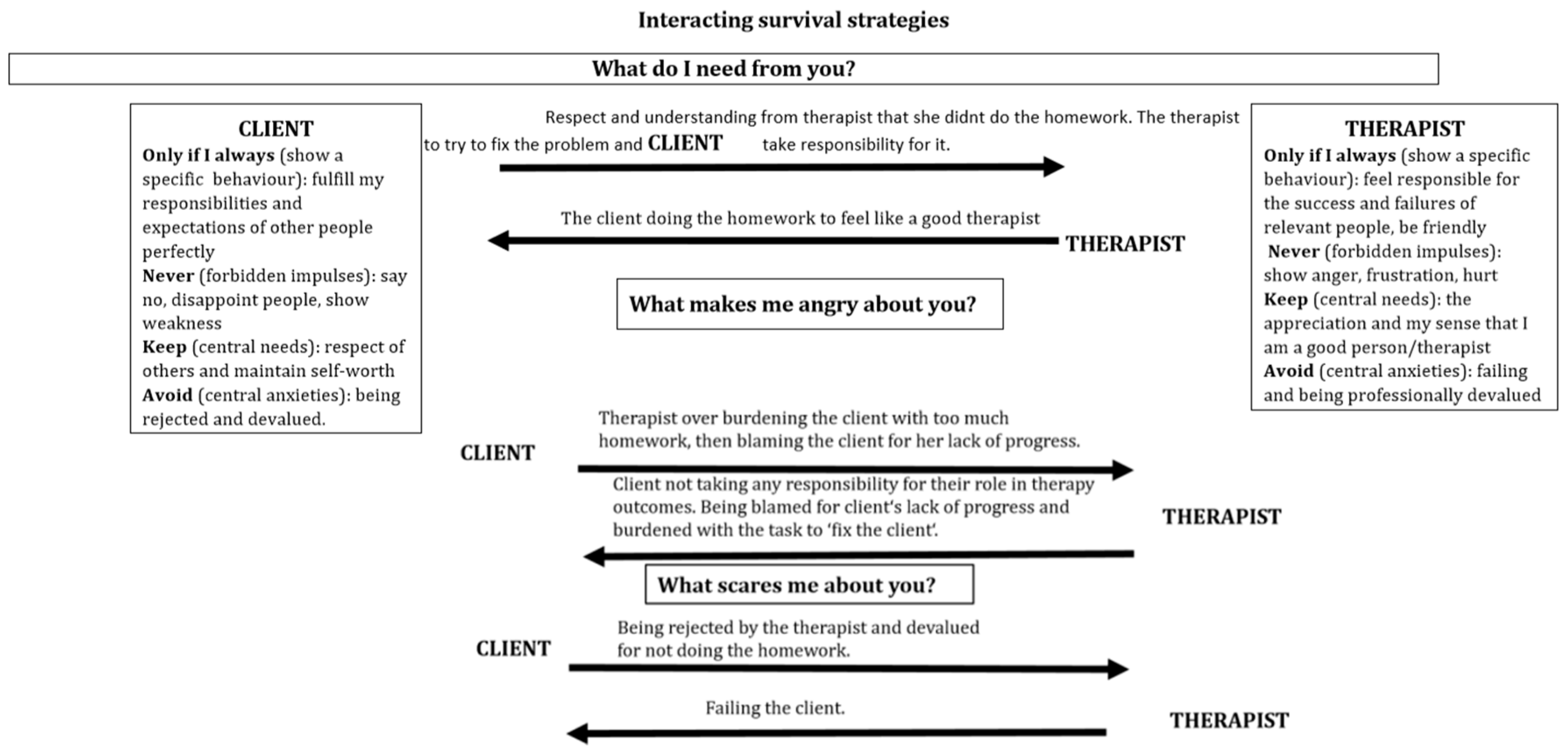

5. Therapeutic Alliance

6. Case Study

What Would an Embodied Therapist do in this Situation?

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, G. The cognitive revolution: A historical perspective. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders; Penguin Group: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy; Lyle Stuart: Oxford, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Craske, G.G.; Treanor, M.; Conway, C.; Zbozinek, T.; Vervliet, B. Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014, 58, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, A.C.; Chapman, J.E.; Forman, E.M.; Beck, A.T. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewelyn, S.; Macdonald, J.; Doorn, K.A.-V. Process–outcome studies. In Handbook of Clinical Psychology; Norcross, J., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Worcester, UK, 2016; pp. 451–463. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, R.A.; Mueser, K.T.; Bolton, E.; Mays, V.; Goff, D. Cognitive therapy for psychosis in schizophrenia: An effect size analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2001, 48, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhar, S.; McKenna, P.J.; Radua, J.; Fung, E.; Salvador, R.; Laws, K.R. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: Systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 204, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfammatter, M. The empirical status of CBT for psychosis: Controlled efficacy, indication and therapeutic factors. A systematic review of meta-analytic findings. Eur. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilling, S.; Bebbington, P.; Kuipers, E.; Garety, P. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: 1. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wykes, T.; Steel, C.; Everitt, B.; Tarrier, N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophr. Bull. 2008, 34, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, G.; Favrod, J.; Trieu, V.H.; Pomini, V. The effect of cognitive behavioural treatment on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 77, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J.; Wade, T.D.; de la Piedad Garcia, X.; Brennan, L. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 1080–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Davis, D.; Freeman, A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, K.R.; Hearon, B.A.; Otto, M.W. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 33, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magill, M.; Ray, L.A. Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2009, 70, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutra, L.; Stathopoulou, G.; Basden, S.L.; Leyro, T.M.; Powers, M.B.; Otto, M.W. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.; Klosko, J.S.; Weishaar, M.E. Schema Therapy: A practitioner’s Guide; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Z.V.; Williams, J.M.; Teasdale, J.D. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.M.; Crane, C.; Barnhofer, T.; Brennan, K.; Duggan, D.; Fennell, M.J.; Hackmann, A.; Krusche, A.; Muse, K.; Rudolf Von Rohr, I.; et al. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Preventing Relapse in Recurrent Depression: A Randomized Dismantling Trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.G.; Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness: Diverse perspectives on its meaning, origins, and multiple applications at the intersection of science and Dhamra. Contemp. Buddhism 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A. Rational-emotive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy: Similarities and differences. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1980, 4, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; McCullough, J.; Klein, D.; Arnow, B.; Dunner, D.; Gelenberg, A.; Markowitz, J.; Nemeroff, C.; Mereroff, C.; Rullell, J.; et al. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 32, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Weitz, E.; Anderson, G.; Hollon, S.D.; va Straten, A. The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 159, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bados, A.; Balaguer, G.; Saldana, C. The Efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and the Problem of Drop-Out. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 63, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbrook, D.; Kirk, J. The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy: Outcome for a large sample of adults treated in routine practice. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005, 43, 1243–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J.S. Complex cognitive therapy treatment for personality disorder patients. Bull. Menn. Clin. 1998, 62, 170–194. [Google Scholar]

- Layden, M.A.; Newman, C.R.; Freeman, A.; Morse, S. Cognitive Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Millon, T. On the genesis and prevalence of Borderline Personality Disorder: A Social Learning Thesis. J. Personal. Disord. 1987, 1, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.E. Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema-Focused Approach; Professional Resource Exchange: Sarasota, FL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou, L. Situated conceptualization: Theory and application. In Perceptual and Emotional Embodiment, Foundations of Embodied Cognition; Coello, Y., Fischer, M., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gjelsvik, B.; Lovric, D.; Williams, M. Embodied cognition and emotional disorders: Embodiment and abstraction in understanding depression. Psychopathol. Rev. 2015, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, S. Change Your Thinking; Marlowe: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin, D.F. Doing CBT: A Comprehensive Guide to Working with Behaviors, Thoughts, and Emotions; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc, R.B. On the primacy of affect. Am. Psychol. 1984, 39, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozolino, L. The Neuroscience of Human Relationships: Attachment and the Developing Brain; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. The Compassionate Mind. A New Approach to Life’s Challenges; Constable Robinson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. Embodied cognition: A field guide. Artif. Intell. 2003, 149, 91–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommel, B. Taking the grounding problem seriously. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 1191–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Rush, A.; Shaw, B.; Emery, G. Cognitive Therapy and Depression; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, T. Embodied cognitive neuroscience and its consequences for psychiatry. Poiesis Prax. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of the Mind; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. Moving beyond cognitive behavior therapy. Psychologist 2009, 22, 400–403. [Google Scholar]

- Leiten, D.; Murray, G. The mind-body relationship in psychotherapy: Grounded cognition as an explanatory framework. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottoboni, G. Grounding clinical and cognitive scientists in an interdisciplinary discussion. Front. Cogn. 2013, 4, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschacher, W.; Jungham, U.; Pfammatter, M. Towards a taxonomy of common factors in psychotherapy-results of an expert survey. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2014, 21, 830–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbusera, L.; Fuchs, T. Embodied understanding: Discovering the body from cognitive science to psychotherapy. In In-Mind Italia. 2013, Volume V, pp. 1–6. Available online: http://it.in-mind.org (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Koch, S.; Morlinghaus, K.; Fuchs, T. The joy dance: Specific effects of single dance intervention on psychiatric patients with depression. Arts Psychother. 2007, 34, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Z.; Ingram, R. Mood priming and construct activation in tests of cognitive vulnerability to unipolar depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1994, 14, 663–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aafjes-Van Doorn, K.; Barber, J. Systematic Review of In-Session Affect Experience in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2017, 41, 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babl, A.; Holtforth, M.G.; Heer, S.; Lin, M.; Stähli, A.; Holstein, D.; Ramseyer, F. Psychotherapy integration under scrutiny: Investigating the impact of integrating emotion-focused components into a CBT-based approach: A study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foa, E.B.; Kozak, M.J. Emotional Processing of Fear: Exposure to Correcctive Information. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 99, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craske, M.G.; Kircanski, K.; Zelikowsky, M.; Mystkowski, J.; Chowdhury, N.; Baker, A. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008, 46, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craske, M. Optimizing Exposure Therapy for Anxiety Disorders: An Inhibitory Learning and Inhibitory Regulation Approach. Verhaltenstherapie 2015, 25, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.C.; Bedard, D.L. Clients’ emotional processing in psychotherapy: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral and process-experiential therapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samoilov, A.; Goldfried, M.R. Role of Emotion in Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2000, 7, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B.; Riggs, D.S.; Massie, E.D.; Yarczower, M. The impact of fear activation and anger on the efficacy of exposure treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav. Ther. 1995, 26, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.A.; Hope, D.A.; Heimberg, R.G. The pattern of subjective anxiety during in-session exposures over the course of cognitive-behavioral therapy for clients with social anxiety disorder. Behav. Ther. 2008, 39, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sassaroli, S.; Brambilla, R.; Cislaghi, E.; Colombo, R.; Centorame, F.; Veronese, G.; Ruggiero, G.M. Emotion-abstraction patterns and cognitive interventions in a single case of standard cognitive-behavioral therapy. Res. Psychother. Psychopathol. Process Outcome 2015, 17, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, S.; Miller, R.; Fehm, L.; Kirschbaum, C.; Fydrich, T.; Ströhle, A. Therapists’ and patients’ stress responses during graduated versus flooding in vivo exposure in the treatment of specific phobia: A preliminary observational study. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 230, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulvenes, P.G.; Berggraf, L.; Wampold, B.E.; Hoffart, A.; Stiles, T.; McCullough, L. Orienting patient to affect, sense of self, and the activation of affect over the course of psychotherapy with cluster C patients. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, E.; Chalder, T.; Ridsdale, L.; Seed, P.; Ogden, J. Investigating the active ingredients of cognitive behaviour therapy and counselling for patients with chronic fatigue in primary care: Developing a new process measure to assess treatment fidelity and predict outcome. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 46, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.M.; Yasinski, C.; Barnes, J.B.; Bockting, C.L. Network destabilization and transition in depression: New methods for studying the dynamics of therapeutic change. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 41, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panksepp, J. Neurologizing the psychology of affects: How appraisal-based constructivism and basic emotion theory can coexist. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ablon, J.S.; Jones, E.E. Psychotherapy process in the NIMH treatment of depression collaborative research program. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 67, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, A.; Hayes, A.M.; Henley, W.; Kuyken, W. Sudden gains in cognitive–behavior therapy for treatment-resistant depression: Processes of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castonguay, L.G.; Goldfried, M.R.; Wiser, S.; Raue, P.J.; Hayes, A.M. Predicting the effect of cognitive therapy for depression: A study of unique and common factors. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.M.; Strauss, J.L. Dynamic systems theory as a paradigm for the study of change in psychotherapy: An application to cognitive therapy for depression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 66, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringer, J.V.; Levitt, H.M.; Berman, J.S.; Mathews, S.S. A study of silent disengagement and distressing emotion in psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. 2010, 20, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, S. Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. Am. Psychol. 1994, 49, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, P.J.; Teasdale, J.D. Interacting cognitive sub-systems: A systemic approach to cognitive-affective inter-action and change. Cogn. Emot. 1991, 5, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.M.; Harris, M.S. The development of an integrative treatment for depression. In Stress, Coping, and Depression; Johnson, S., Hayes, A.M., Field, T., Schneiderman, N., McCabe, P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.M. Facilitating emotional processing in depression: The application of exposure principles. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 4, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raes, F.; Hermans, D.; Williams, J.; Eelen, P. Reduced autobiographical memory specificity and affect regulation. Cogn. Emot. 2006, 20, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, E.; Moberly, N.; Moulds, M. Processing mode causally influences emotional reactivity: Distinct effects of abstract versus concrete construal on emotional response. Emotion 2008, 8, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greenberg, L.S.; Safran, J.D. Emotion in Psychotherapy. Am. Psychol. 1989, 4, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, L.E.; Clarkin, J.F.; Bongar, B. Guidelines for the Systematic Treatment of the Depressed Patient; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Iwakabe, S.; Rogan, S.; Stalikas, A. The Relationship between Client Emotional Expressions, Therapist Interventions, and the Working Alliance: An Exploration of Eight Emotional Expression Events. J. Psychother. Integr. 2000, 10, 4, 375–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelton, W.J. Emotional processes in psychotherapy: Evidence across therapeutic modalities. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2004, 11, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znoj, H.-J. Die therapeutische Beziehung aus verhaltenstherapeutischer Sicht. In Die Therapeutische Beziehung; Roessler, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, J.F.; Castonguay, L.G.; Pincus, A.L. Trainee theoretical orientation: Profiles and potential predictors. J. Psychother. Integr. 2009, 19, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.M.; Biyanova, T.; Elhai, J.D.; Schnurr, P.; Coyne, J.C. What do psychotherapists really do in practice? An Internet study of over 2.000 practitioners. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2010, 47, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messer, S.B. Introduction to the special issue on assimilative integration. J. Psychother. Integr. 2001, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.; Watson, J.; Greenberg, L.S.; Timulak, L.; Freire, E. Research on humanistic-experiential psychotherapies. In Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 6th ed.; Lambert, M.J., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L.S. Emotion-Focused Therapy: Coaching Clients to Work through Their Feelings; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Greenburg, L.S.; Goldman, R.N. Emotion-Focused Couples Therapy: The Dynamics of Emotion, Love and Power; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L.S.; Watson, J.C. Emotion-Focused Therapy for Depression; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pavio, S.C. Essentia processes in emotion-focused therapy. Psychotherapy 2013, 50, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. The future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades. Emot. Rev. 2010, 2, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol. Inq. Int. J. Adv. Psychol. Theory 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, E.B.; Barlow, D. A New Unified Treatment Approach for Emotional Disorders Based on Emotion Science. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berking, M.; Wupperman, P.; Reichardt, A.; Pejic, T.; Dippel, A.; Znoj, H. General emotion-regulation skills as a treatment target in psychotherapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008, 46, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, D.H.; Allen, L.B.; Choate, M.L. Toward a Unified Treatment for Emotional Disorders-Republished Article. Behav. Ther. 2016, 47, 838–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The Extended Process Model of Emotion Regulation: Elaborations, Applications, and Future Directions. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koole, S.L.; Veenestra, L. Does Emotion Regulation Occur Only inside People’s Heads? Toward a Situated Cognition Analysis of Emotion-Regulatory Dynamics. Psychol. Inq. 2005, 26, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauke, G.; Lohr, C.; Pietrzak, T. Moving the mind: Embodied cognition in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). In European Psychotherapy 2016/2017: Embodiment in Psychotherapy; Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2016; Volume 13, pp. 154–178. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands, M. The New Science of Mind: From Extended Mind to Embodied Phenomenology; MIT Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M. Six views of embodied cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2002, 9, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, L. Embodied Cognition; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Glenberg, A. Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 2010, 1, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, M.; Codispoti, M.; Cuthbert, B.; Lang, P. Emotion and motivation, I: Defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion 2001, 1, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsalou, L. Perceptual symbol systems. Behav. Brain Sci. 1999, 22, 577–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallese, V. The ‘shared manifold’ hypothesis. From mirror neurons to empathy. J. Conscious. Stud. 2001, 8, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gallese, V.; Keysers, C.; Rizzolatti, G. A unifying view of the basis of social cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004, 8, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenberg, J.; Witt, J.; Metcalfe, J. From the Revolution to Embodiment: 25 Years of Cognitive Psychology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesario, J.; McDonald, M. Bodies in Context: Power Poses as a Computation of Action Possibility. Soc. Cogn. 2013, 31, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, J.D.; Lacasse, K. Bodily Influences on Emotional Feelings: Accumulating Evidence and Extensions of William James’s Theory of Emotion. Int. Soc. Res. Emot. 2014, 6, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranehill, E.; Dreber, A.; Johannesson, M.; Leiberg, S.; Sul, S.; Weber, R.A. Assessing the Robustness of Power Posing: No Effect on Hormones and Risk Tolerance in a Large Sample of Men and Women. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, A.J.; Mason, M.F.; Ames, D.R. The powerful size others down: The link between power and estimates of other’s size. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, D.R.; Cuddy, A.J.; Yap, A.J. Review and Summary of Research on the Embodied Effects of Expansive (vs. Contractive) Nonverbal Displays. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacharkulksemsuk, T.; Reit, E.; Khambatta, P.; Eastwick, P.W.; Finkel, E.J.; Carney, D.R. Dominant, open nonverbal displays are attractive at zero-acquaintance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4009–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, D.R.; Cuddy, A.J.; Yap, A.J. Power posing: Brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, T.F.; Harmon-Jones, E. Embodied emotion: The influence of manipulated facial and bodily states on emotive responses. Cogn. Sci. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondloch, C.J.; Nelson, N.L.; Horner, M. Asymmetries of influence: Differential effects of body postures on perceptoiins of emotional facial expressions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.; John, O. Individual differences in two emotional regulation processes. Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joorman, J.; Gotlib, I. Emotion regulation in depression: Relation to cognitive inhibition. Cogn. Emot. 2010, 24, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, Z.; Williams, J.; Teasdale, J. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, G.; Dall’Occhio, M. Emotional Activation Therapy (EAT): Intense work with different emotions in a cognitive behavioral setting. Eur. Psychother. 2013, 11, 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, G.; Dall’Occhio, M. Emotionale Aktivierungstherapie (EAT): Embodimenttechniken im Emotionalen Feld; Schattauer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pollatos, O.; Matthias, E.; Keller, J. When interoception helps to overcome negative feelings caused by social exclusion. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulz, S.K. Strategische Kurzzeittherapie—Wege Zur Effizienten Psychotherapie; CIP-Medien: München, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fruzzetti, A.E.; Shenk, C. Fostering validating responses in families. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2008, 6, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grawe, K. Psychotherapie ohne Grenzen. Von den Therapieschulern zur Allgemeinen Psychotherapie. Verhaltenstherap. Psychosoz. Prax. 1994, 26, 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, G. Reinforcing goal commitment: Work with personal values in Strategic Behavioral Therapy (SBT). Eur. Psychother. 2010, 9, 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, S.; Zhou, H.; Monteoene, G.; Majka, E.; Quinn, K.; Ball, A.; Norman, G.; Semin, G.; Cacioppo, J. You are in sync with me. Neuroscience 2014, 277, 842–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catmur, C.; Heyes, C. Is it what you do, or when you do it? The roles of contingency and similarity in pro-social effects of imitation. Cogn. Sci. 2013, 37, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Werner, K.; Raab, M. Moving to Solution: Effects of Movement Priming on Problem Solving. Exp. Psychol. 2013, 60, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natanzon, M.; Ferguson, M. Goal pursuit is grounded: The link between forward movement and achievement. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, L.; Lumsden, J.; Richardson, M.; Macrae, C. Do birds of a feather move together? Group membership and behavioral synchrony. Exp. Brain Res. 2011, 211, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, S.; Holland, R.; Hengstler, M.; van Knippenberg, A. Body locomotion as regulatory process. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 549–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, T.; Hauke, G.; Lohr, C. Connecting Couples Intervention: Improving couples’ empathy and emotional regulation using embodied empathy mechanisms. Eur. Psychother. 2016, 13, 66–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak, T.; Lohr, C.; Hauke, G.; Jahn, B. Imitation and Synchronisation in Schema Work with Couples: Developing a new love strategy. In Symposium: Embodied Cognition in Cognitive Therapy-Bodies and Minds Together, Proceedings of the 8th World Congress in Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies, Melbourne, Australia, 23 June 2016; The Australian Association for Cognitive and Behaviour Therapy: Waratah, Austrilia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koole, S.; Tschacher, W. Synchrony in Psychotherapy: A Review and an Integrative Framework for the Therapeutic Alliance. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schule, D.; Eifert, G. What to do when manuals fail? The dual model of psychotherapy. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2002, 9, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacharkulksemsuk, T.; Fredrickson, B. Strangers in sync: Achieving embodied rapport through shared movements. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, R.; Magori-Cohen, R.; Galiti, G.; Singer, M.; Louzoun, Y. Mother and infant coordinate heart beat rhythms through episodes of interaction synchrony. Infant Behav. Dev. 2011, 34, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marci, C.; Orr, S. The effect of emotional distance on psychophysiological concordance and perceived empathy between patient and interviewer. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2006, 31, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grecucci, A.; Theuninck, A.; Frederickson, J.; Job, R. Mechanisms of social emotion regulation: From neuroscience to psychotherapy. In Handbook on Emotion Regulation: Processes, Cognitive Effects and Social Consequences; Bryant, M., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Haupauge, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Peri, T.; Gofman, M.; Tal, S.; Tuval-Mashiach, R. Embodied simulation in exposure-based therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder—A possible integration of cognitive behavioral theories, neuroscience and psychoanalysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2015, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pietrzak, T.; Lohr, C.; Jahn, B.; Hauke, G. Embodied Cognition and the Direct Induction of Affect as a Compliment to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8030029

Pietrzak T, Lohr C, Jahn B, Hauke G. Embodied Cognition and the Direct Induction of Affect as a Compliment to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. Behavioral Sciences. 2018; 8(3):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8030029

Chicago/Turabian StylePietrzak, Tania, Christina Lohr, Beverly Jahn, and Gernot Hauke. 2018. "Embodied Cognition and the Direct Induction of Affect as a Compliment to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy" Behavioral Sciences 8, no. 3: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8030029