Determinants in Competition between Cross-Sector Alliances

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review Findings

2.1. Directions for Literature Review

2.2. People’s Viewpoint Depths

2.3. People’s Predictive Evaluations

2.4. Organizations’ Actions

2.5. Competitors’ Responses

2.6. Reach Duration

2.7. People’s Choices

2.8. Competitive Environments

3. Framework

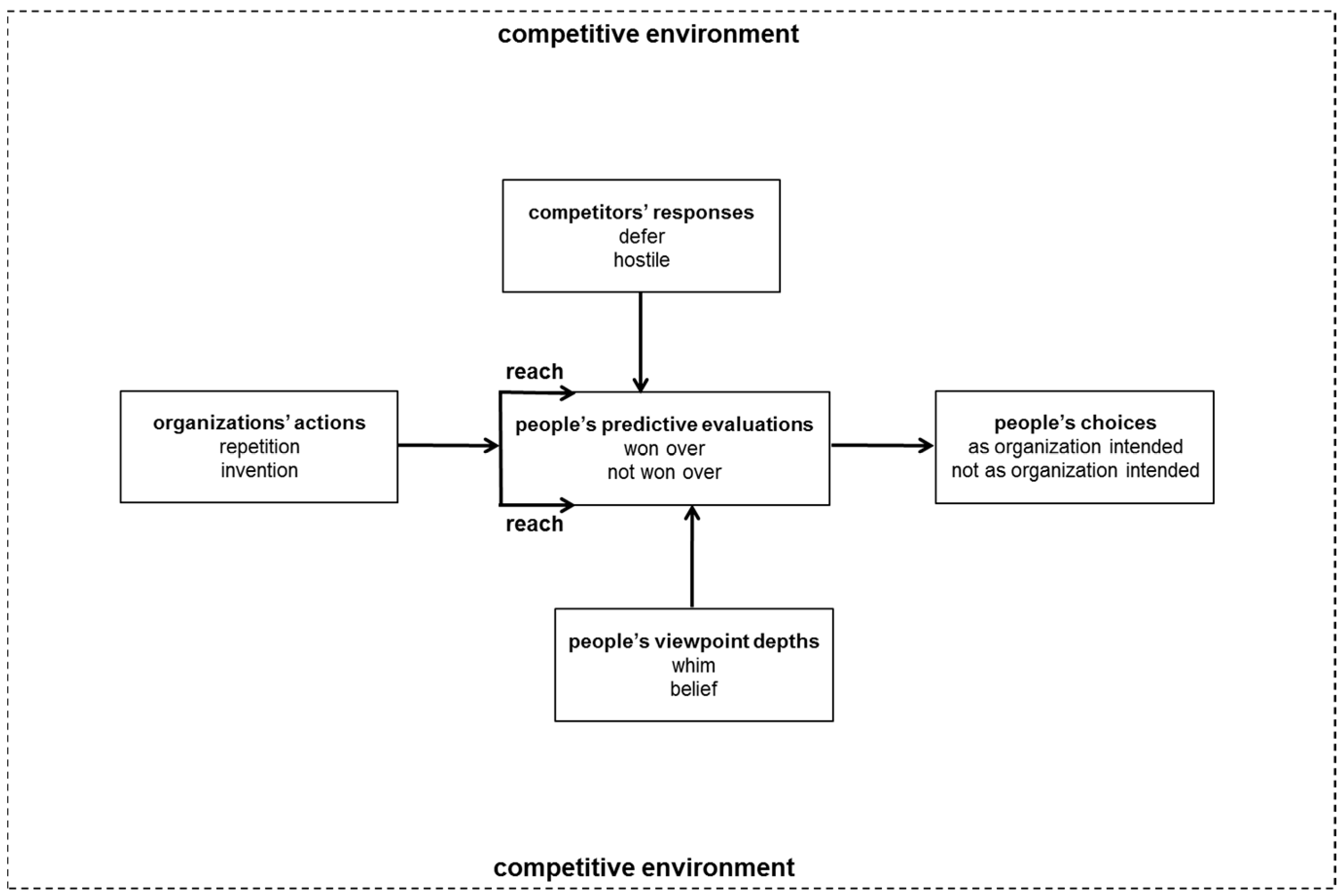

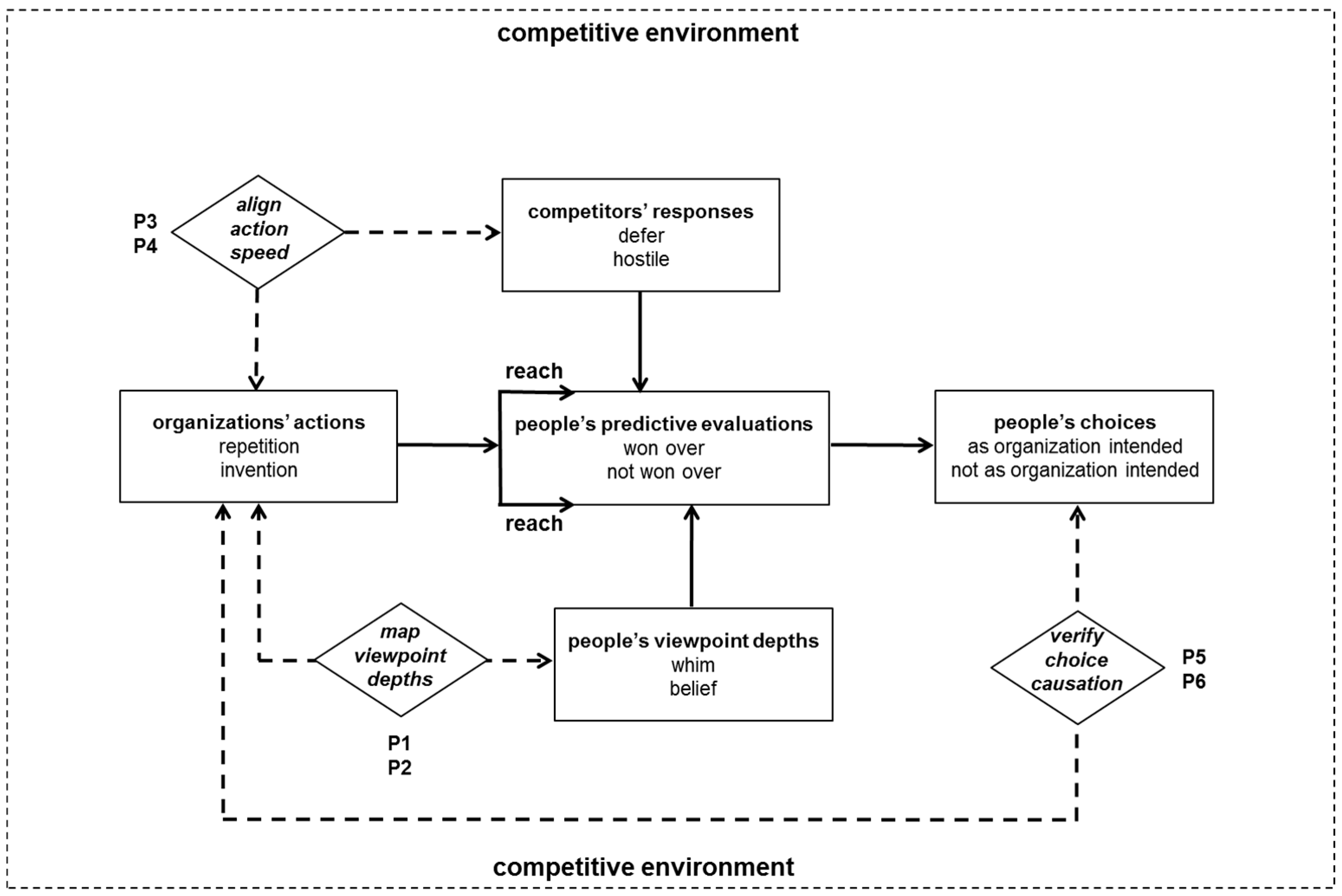

3.1. Overview of Framework

3.2. Propositions

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Research

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abimbola, Seye, Asmat Ullah Malik, and Ghulam Farooq Mansoor. 2013. The Final Push for Polio Eradication: Addressing the Challenge of Violence in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria. PLoS Medicine 10: e1001529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, Alexander M., Calum Davey, James R. Hargreaves, and Richard J. Hayes. 2015. Re-analysis of health and educational impacts of a school-based deworming programme in western Kenya: A pure replication. International Journal of Epidemiology 44: 1572–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancona, Deborah G., Paul S. Goodman, Barbara S. Lawrence, and Michael L. Tushman. 2001. Time: A new research lens. Academy of Management Review 26: 645–63. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Michael L. 2010. Neural reuse: A fundamental organizational principle of the brain. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 245–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashenfelter, Orley C., Stephen Ciccarella, and Howard J. Shatz. 2007. French Wine and the U.S. Boycott of 2003: Does Politics Really Affect Commerce? Journal of Wine Economics 2: 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, James E. 2000. Strategic collaboration between nonprofits and businesses. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 29: 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Lisa F. 2017. The theory of constructed emotion: An active inference account of interoception and categorization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 12: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, Josh, and Shelby Baird. 2014. The shooting cycle. Connecticut Law Review 46: 1513–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bores, Cristina, Carme Saurina, and Ricard Torres. 2003. Technological convergence: A strategic persective. Technovation 23: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowcott, Owen, and Richard Adams. 2016. Human rights group condemns Prevent anti-radicalisation strategy. The Guardian, July 13. [Google Scholar]

- Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan L. Star. 1999. Sorting Things out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bridoux, Flore, Ken G. Smith, and Curtis M. Grimm. 2013. The management of resources: Temporal effects of different types of actions on performance. Journal of Management 39: 928–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulle, Robert J. 2014. Institutionalizing delay: Foundation funding and the creation of U.S. climate change counter-movement organizations. Climatic Change 122: 681–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummans, Boris H. J. M., Linda L. Putnam, Barbara Gray, Ralph Hanke, Roy J. Lewicki, and Carolyn Wiethoff. 2008. Making sense of intractable multiparty conflict: A study of framing in four environmental disputes. Communication Monographs 75: 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, Robert A., Clayton M. Christensen, and Steven C. 1996. Strategic Management of Technology and Innovation, 2nd ed. Chicago: Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, Thomas A., Judy K. Frels, and Vijay Mahajan. 2003. Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 31: 109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calloway-Thomas, Carolyn, and John L. Lucaites. 2006. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Sermonic Power of Public Discourse. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, Gail A., and Stephen Grossberg. 2003. Adaptive resonance theory. In The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks, 2nd ed. Edited by M. A. Arbib. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cerna, Lucie. 2014. Attracting High-Skilled Immigrants: Policies in Comparative Perspective. International Migration 52: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, Roger, and James Ciment. 2014. Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints and Voices, 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ming-Jer, and Danny Miller. 2012. Competitive Dynamics: Themes, Trends, and a Prospective Research Platform. Academy of Management Annals 6: 1–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Andy. 2015. Embodied prediction. In Open MIND. Edited by Thomas Metzinger and Jennifer. M. Windt. Frankfurt: MIND Group, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, Jay A. 1998. Winning ‘Em over: A New Model for Managing in the Age of Persuasion. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, Kevin P., and John Horn. 2009. Predicting your competitor’s reaction. Harvard Business Review 87: 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Crossan, Mary, Miguel Pina E. Cunha, Dusya Vera, and João Cunha. 2005. Time and Organizational Improvisation. Academy of Management Review 30: 129–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Callum. 2016. Man kills his friend in argument. The Telegraph, March 7. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Jason P., Kathleen M. Eisenhardt, and Christopher B. Bingham. 2007. Developing theory through simulation methods. Academy of Management Review 32: 480–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Will. 2016. Faction stations: Which Brexit campaign is which? The Guardian, January 31. [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu, Carsten K. W. 2006. When Too Little or Too Much Hurts: Evidence for a Curvilinear Relationship Between Task Conflict and Innovation in Teams. Journal of Management 32: 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, Thomas W. 2003. Despite Good Intentions: Why Development Assistance to the Third World Has Failed. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnik, Adam. 2007. Understanding Terrorist Innovation Trends. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dubin, Robert. 1969. Theory Building. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Mark, Randi Hjalmarsson, and Brian A. Jacob. 2011. The Short-Term and Localized Effect of Gun Shows: Evidence from California and Texas. Review of Economics and Statistics 93: 786–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Shelly Chaiken. 1995. Attitude strength, attitude structure, and resistance to change. In Attitude Strength: Antecedents and Consequences. Edited by Richard E. Petty and Jon A. Krosnick. London: Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 413–32. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal 32: 543–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Behnam N. Tabrizi. 1995. Accelerating adaptative processes: Product innovation in the global computer industry. Administrative Science Quarterly 40: 84–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlanger, Steven. 2016. Fractures From ‘Brexit’ Vote Spread Into Opposition Labour Party. The New York Times, June 26. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Alberto M. 2015. Here to Stay and Growing: Combating ISIS Propaganda Networks. The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/IS-Propaganda_Web_English_v2.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2017).

- Fershtman, Chaim, and Kenneth L. Judd. 1987. Equilibrium Incentives in Oligopoly. The American Economic Review 77: 927–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Charles H. 1998. Clockspeed: Winning Industrial Control in the Age of Temporary Advantage. New York: Perseus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Flach, Peter A., and Antonis M. Hadjiantonis. 2013. Abduction and Induction: Essays on Their Relation and Integration. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Stephen. 2016. Addressing the causes of mass migrations: Leapfrog solutions for mutual prosperity growth between regions of emigration and regions of immigration. Technology in Society 46: 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Wendy S., and Sabrina L. K. Gallard. 2005. Concept mediation in trilingual translation. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 12: 1082–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryer, Roland G., and Glenn C. Loury. 2005. Affirmative action in winner-take-all markets. Journal of Economic Inequality 3: 263–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, Raghu, Sanjay Jain, and Phillipp Tuertscher. 2008. Incompleteness by design and designing for incompleteness. Organizational Studies 29: 351–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Paul, John Horgan, Samuel T. Hunter, and Lily D. Cushenbery. 2013. Malevolent creativity in terrorist organizations. The Journal of Creative Behaviour 47: 125–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Casseres, Benjamin. 2003. Competitive advantage in alliance constellations. Strategic Organization 1: 327–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, Henrich. R. 2005. Interorganizational Learning before 9/11. International Public Management Journal 8: 383–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, Peter H. 2005. Nationalism, Indignation, and China’s Japan Policy. SAIS Review of International Affairs 25: 105–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohwy, Jakob. 2013. The Predictive Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Inman, Phillip. 2016. Mervyn King: Treasury’s exaggerated Brexit claims backfired. The Guardian, June 27. [Google Scholar]

- Jennissen, Roel. 2007. Causality Chains in the International Migration Systems Approach. Population Research and Policy Review 26: 411–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Nicholas J. 2009. A Second Amendment Moment: The Constitutional Politics of Gun Control. Brooklyn Law Review 71: 715. [Google Scholar]

- Kabra, Gaurav, Anbanandam Ramesh, and Kaur Arshinder. 2015. Identification and prioritization of coordination barriers in humanitarian supply chain management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 13: 128–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, Dan, Hank Jenkins-Smith, and Donald Braman. 2010. Cultural Cognition of Scientific Consensus. Journal of Risk Research 14: 147–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, Dan M., Ellen Peters, Erica C. Dawson, and Paul Slovic. 2013. Motivated Numeracy and Enlightened Self-Government. Behavioural Public Policy 1: 54–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Kyun S., and Yorgo Pasadeos. 2007. Study of partisan news readers reveals hostile media perceptions of balanced stories. Newspaper Research Journal 28: 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimble, Chris, Corinne Grenier, and Karine Goglio-Primard. 2010. Innovation and Knowledge Sharing Across Professional Boundaries: Political Interplay between Boundary Objects and Brokers. International Journal of Information Management 30: 437–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kline, Rex B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Koschmann, Matthew A., Timothy R. Kuhn, and Michael D. Pfarrer. 2012. A communicative framework of value in cross-sector partnerships. Academy of Management Review 37: 332–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchler, Hannah, and Geoff Dyer. 2015. Abdullah-X takes on Isis in social media fight. The Financial Times, December 13. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, Ellen J. 1975. The Illusion of Control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 32: 311–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurienti, Paul J., Mark T. Wallace, Joseph A. Maldjian, Christina M. Susi, Barry E. Stein, and Jonathan H. Burdette. 2003. Cross-modal sensory processing in the anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortices. Human Brain Mapping 19: 213–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Khai. S., Pheng L. Chng, and Chow H. Wee. 1994. The art and the science of strategic marketing: Synergizing Sun Tzu’s Art of War with game theory. Journal of Strategic Marketing 2: 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, David T. 2000. Industry evolution and competence development: The imperatives of technological convergence. International Journal of Technology Management 19: 699–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindaman, Kara, and Donald P. Haider-Markel. 2002. Issue Evolution, Political Parties, and the Culture Wars. Political Research Quarterly 55: 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, Peter E. D., Pauline Teo, Murray Davidson, Shaun Cumming, and John Morrison. 2016. Building absorptive capacity in an alliance: Process improvement through lessons learned. International Journal of Project Management 34: 1123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchins, Abraham S., and Edith H. Luchins. 1987. Einstellung effects. Science 238: 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2007. Local Impacts of the Balloon Effect of Border Law Enforcement. Geopolitics 12: 280–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Peter M., and Vinit Desai. 2010. Failing to learn? The effects of failure and success on organizational learning in the global orbital launch vehicle industry. Academy of Management Journal 53: 451–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Arvind, and Marshall Van Alstyne. 2014. The dark side of the sharing economy … and how to lighten it. Communications of the ACM 57: 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Alasdair, Udechukwu Ojiako, and Max Chipulu. 2014. Micro-political risk factors for strategic alliances: Why Machiavelli’s animal spirits matter. Competition and Change 18: 438–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Barbara, and Jacob Goldstein. 2007. Big Pharma Faces Grim Prognosis: Industry Fails to Find New Drugs to Replace Wonders Like Lipitor. Wall Street Journal, December 6, AI. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, Rowena, and Anushka Asthana. 2016. Brexit would put a bomb under UK economy, says Cameron. The Guardian, June 6. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, John E., Tonia S. Heffner, Gerald F. Goodwin, Eduardo Salas, and Janis A. Cannon-Bowers. 2000. The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 85: 273–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacAskill, William. 2015. Doing Good Better—Effective Altruism and a Radical Way to Make a Difference. New York: Avery. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, Campbell R., Stanley L. Brue, and Sean M. Flynn. 2014. Economics: Principles, Problems and Policies, 20th ed. Boston: Irvin/McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Melzer, Scott. 2012. Gun Crusaders: The NRA’s Culture War. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, Joergen O. 2014. Maskirovka: Russia’s Masterful Use of Deception in Ukraine. The Huffington Post, April 23. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, Susan, Lori Ferzandi, and Katherine Hamilton. 2010. Metaphor No More: A 15-Year Review of the Team Mental Model Construct. Journal of Management 36: 876–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, K. Sridhar. 1988. Product and Price Competition in a Duopoly. Marketing Science 7: 141–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, Christine, and Anne S. Miner. 1998. Organizational improvisation and organizational memory. Academy of Management Review 23: 698–723. [Google Scholar]

- Normann, Hans-Theo. 2000. Conscious Parallelism in Asymmetric Oligopoly. Metroeconomica 51: 343–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, Enrique, and Gary S. Lynn. 2012. The impact of adding improvisation to sequential NPD processes on cost: The moderating effects of turbulence. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 16: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Obadare, Ebenezer. 2005. A crisis of trust: History, politics, religion and the polio controversy in Northern Nigeria. Patterns of Prejudice 39: 265–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, Brian A. 2013. The National Rifle Association and the Media: The Motivating Force of Negative Coverage. London: Arktos Media Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, Roxy, and Jay L. Devore. 2011. Statistics: The Exploration and Analysis of Data. Boston: Cengage. [Google Scholar]

- Poczter, Sharon L., and Luka M. Jankovic. 2014. The Google Car: Driving Toward a Better Future? Journal of Business Case Studies 10: 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, Ashutosh, and Suresh P. Sethi. 2003. Competitive advertising under uncertainty: A stochastic differential game approach. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications 123: 163–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Maria J, and Mohammed M. Hafez. 2010. Terrorist Innovations in Weapons of Mass Effect: Preconditions, Causes and Predictive Indicators. Report No. ASCO 2010-019. Washington: The Defense Threat Reduction Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Rein, Melanie, and Leda Stott. 2009. Working together: Critical perspectives on six cross-sector partnerships in southern Africa. Journal of Business Ethics 90: 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, Brett. 2005. Building an Electronic Repertoire of Contention. Social Movement Studies 4: 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufin, Carlos, and Miguel Rivera-Santos. 2010. Between commonwealth and competition: Understanding the governance of public–private partnerships. Journal of Management 36: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schroefl, Josef, and Stuart J. Kaufman. 2014. Hybrid Actors, Tactical Variety: Rethinking Asymmetric and Hybrid War. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 37: 862–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J., and S. Moreland. 2014. The Islamic State is a Hybrid Threat: Why Does That Matter? Small Wars Journal, December 2. [Google Scholar]

- Selsky, John W., and Barbara Parker. 2005. Cross-Sector Partnerships to Address Social Issues: Challenges to Theory and Practice. Journal of Management 31: 849–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, Anil K. 2015. The Cybernetic Bayesian Brain—From Interoceptive Inference to Sensorimotor Contingencies. In Open MIND: 35(T). Edited by Thomas Metzinger and Jennifer M. Windt. Frankfurt: MIND Group. [Google Scholar]

- Simsek, Zeki, Brian C. Fox, and Ciaran Heavey. 2014. "What’s Past Is Prologue": A Framework, Review, and Future Directions for Organizational Research on Imprinting. Journal of Management 41: 288–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, Martijntje. 2006. Taming monsters: The cultural domestication of new technologies. Technology in Society 28: 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Erika, Guy Chazan, and Sam Jones. 2015. Isis Inc: How oil fuels the jihadi terrorists. The Financial Times, October 14. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, Gilvan C., Barry L. Bayus, and Harvey M. Wagner. 2004. New-product strategy and industry clockspeed. Management Science 50: 537–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, Mike. 2016. Obama Administration Rolls out Recommendations for Driverless Cars. The Wall Street Journal, September 19. [Google Scholar]

- Staw, B. M. 1976. Knee-deep-in-the-big-muddy: A study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action. Organisational Behaviour and Human Performance 16: 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, John D. 2000. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, Donald J., and Andrew S. Creed. 2014. Sharpening the Focus of Force Field Analysis. Journal of Change Management 14: 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydow, Jörg, Georg Schreyogg, and Jochen Koch. 2009. Organizational path dependence: Opening the black box. Academy of Management Review 34: 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyree, Stephanie, and Maron Greenleaf. 2009. The Environmental Injustice of "Clean Coal": Expanding the national conversation on carbon capture and storage technology to include analysis of potential environmental justice impacts. Environmental Justice 2: 167–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, Andreas, Klaus Rothermund, and Jochen Brandtstädter. 2008. Interpreting ambiguous stimuli: Separating perceptual and judgmental biases. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44: 1048–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, Michael. 2014. How the NRA rewrote the Second Amendment. Politico, May 19. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, Matthew. 2016. Boris Johnson’s Independence Day claim nonsense, says David Cameron. The Guardian, June 22. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, Karl E. 2001. Making Sense of the Organization. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, Karl. E. 1984. Small wins. American Psychologist 39: 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetten, David. 1989. What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review 14: 490–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, Glen, Alan M. Saks, and Sterling Hook. 1997. When success breeds failure: The role of self-efficacy in escalating commitment to a losing course of action. Journal of Organizational Behavior 18: 415–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, Mary. 2016. Driverless cars could improve safety, but impact on jobs, transit questioned. Chicago Tribune, July 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Ming, and Xiao-Ping Chen. 2003. Achieving cooperation in multiparty alliances: A social dilemma approach to partnership management. Academy of Management Review 28: 587–605. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs | Explanation | References |

|---|---|---|

| People’s predictive evaluations (won over—not won over) | People are more likely to be won over if predictive evaluations suggest a positive balance relative to their current situations | (Clark 2015; Hohwy 2013; Seth 2015) |

| Organizations’ actions (repetition—invention) | Winning involves determining the appropriate amount of originality in what is offered and how it is offered | (Dolnik 2007; Rasmussen and Hafez 2010) |

| Reach duration (zero—indefinite) | The longer the reach duration, the more potential for competitors’ responses to exert influence over people’s predictive evaluations | (Ancona et al. 2001; Bridoux et al. 2013) |

| People’s viewpoint depths (whim—belief) | Winning depends much upon the profoundness of people’s points of view, with deeply held beliefs being most resistant to change | (Eagly and Chaiken 1995; Kahan et al. 2010) |

| Competitors’ responses (defer—hostile) | Across sectors, competitors’ responses can range from none immediately to retaliatory counteractions to protect positions | (Coyne and Horn 2009; Fershtman and Judd 1987; Moorthy 1988 ) |

| People’s choices (as intended—not as intended) | People’s choices can be as intended to arise from the organizations’ actions, but unintended consequences can also arise | (Melzer 2012; Patrick 2013; Sterman 2000) |

| Competitive environments (duopoly—winner-takes all) | Competitive environments cross different types of sectors as governments and not-for-profits also compete to win people over | (Cerna 2014; Lindaman and Haider-Markel 2002; McConnell et al. 2014) |

| Propositions | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CSA will increase the number of people won over through actions that link different viewpoint depths |

|

| 2 | CSA will increase the number of people won over through actions that are congruent with local viewpoint depths |

|

| 3 | CSA will increase the number of people won over through actions that outpace the speed of competition |

|

| 4 | CSA will increase the number of people won over through actions that are not delayed by cross-sector bureaucracy |

|

| 5 | CSA will increase the number of people won over through identification of true and false choice causation |

|

| 6 | CSA will increase the number of people won over through regular re-evaluations of choice causation |

|

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fox, S.; Kauttio, J.; Mubarak, Y.; Niemisto, H. Determinants in Competition between Cross-Sector Alliances. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7030031

Fox S, Kauttio J, Mubarak Y, Niemisto H. Determinants in Competition between Cross-Sector Alliances. Administrative Sciences. 2017; 7(3):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7030031

Chicago/Turabian StyleFox, Stephen, Janne Kauttio, Yusuf Mubarak, and Hannu Niemisto. 2017. "Determinants in Competition between Cross-Sector Alliances" Administrative Sciences 7, no. 3: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci7030031