Production and Maintenance Planning for a Deteriorating System with Operation-Dependent Defectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

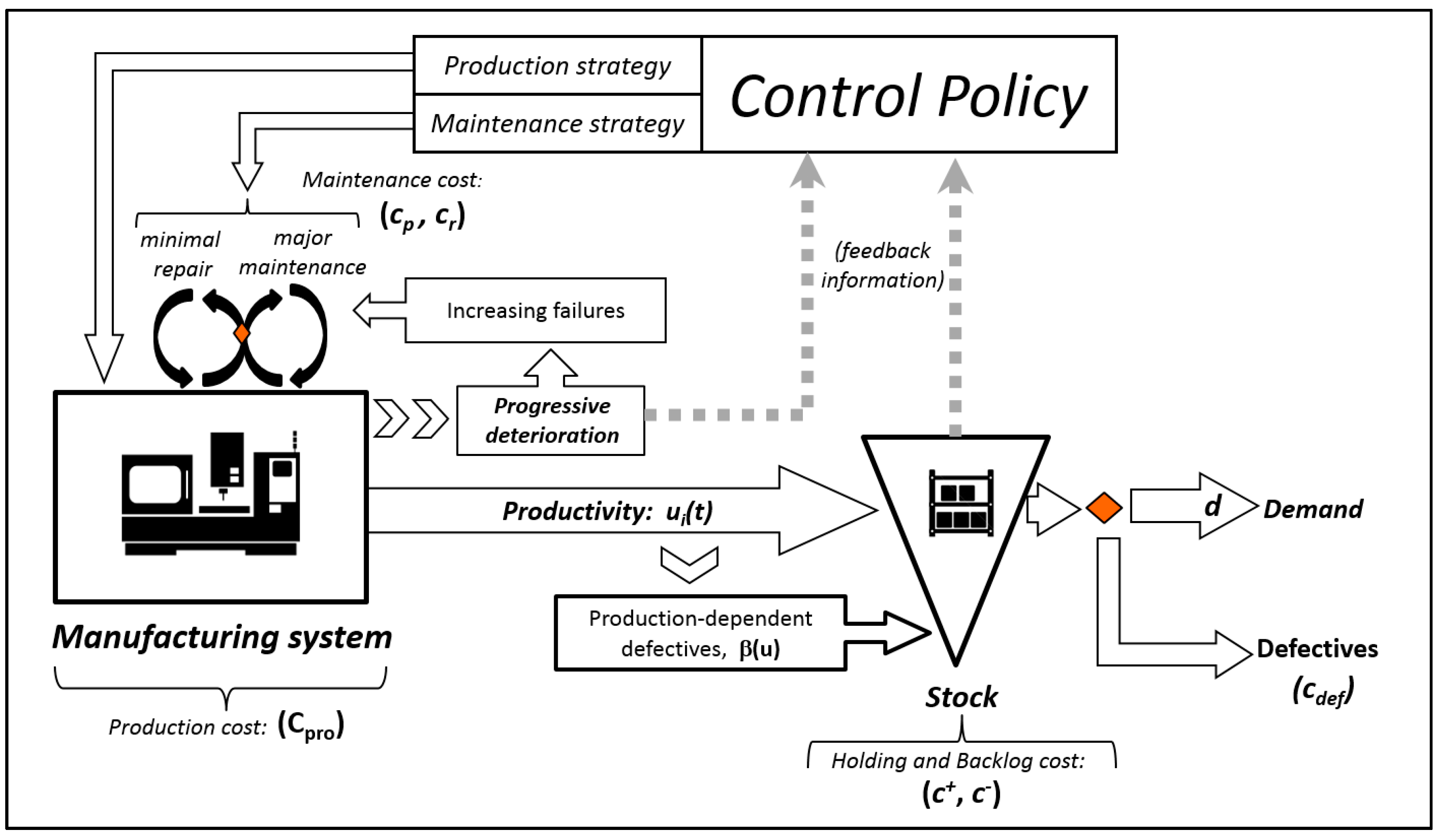

2. Industrial Motivation

3. Notation and Problem Statement

3.1. Notations

| Inventory level at time t | |

| Age of the machine at time t | |

| Production rate at time t | |

| Stochastic process | |

| Maximal production rate | |

| Productivities of the machine | |

| Control variable for the repair/major maintenance policy at time t | |

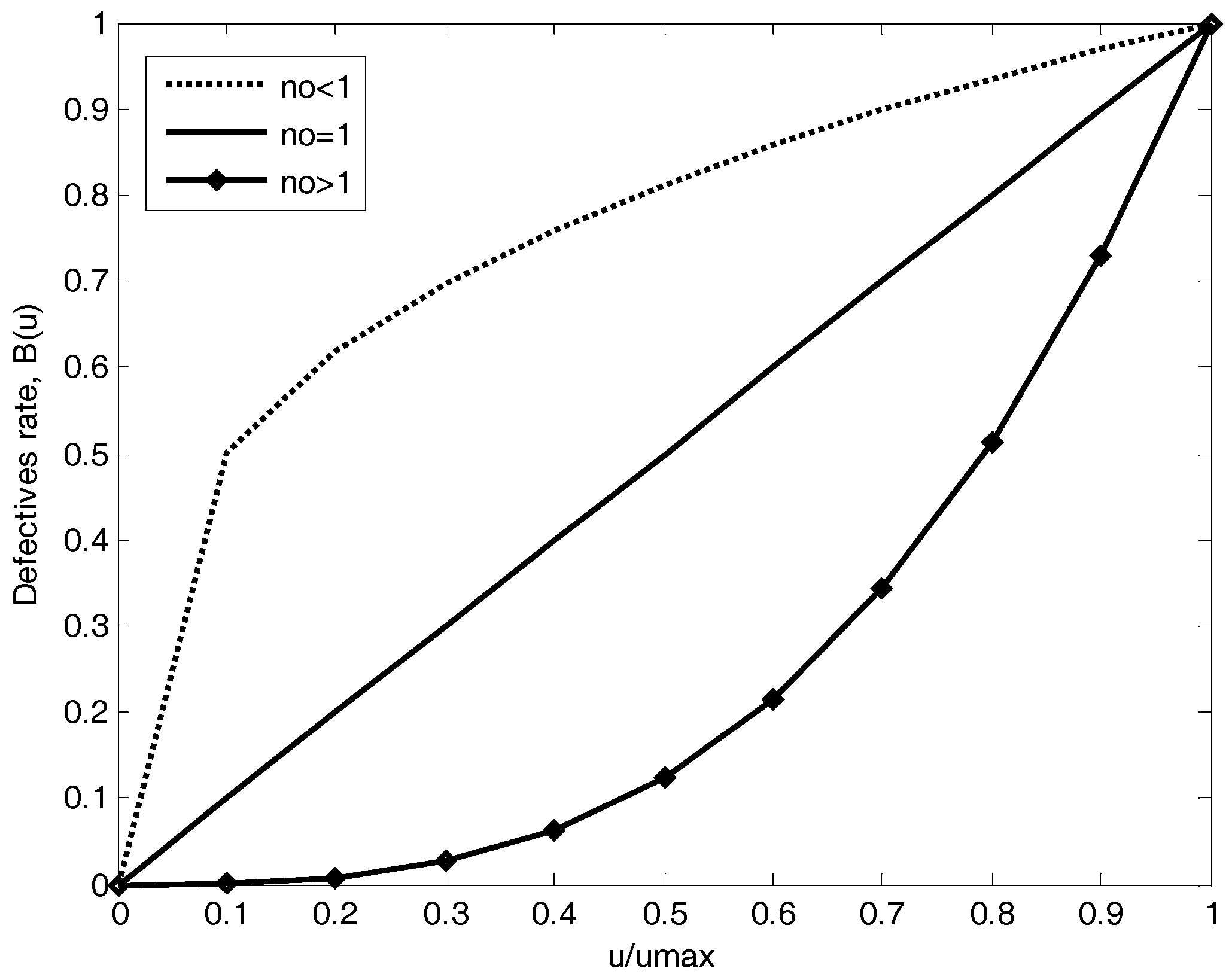

| Rate of defectives | |

| Constant demand rate of products | |

| Set of states of the machine | |

| Discount rate | |

| Limiting probability at mode i | |

| (·) | Transition rate from mode α to mode α′ |

| Instantaneous cost function | |

| Expected discounted cost function | |

| Value function | |

| Jump time of ξ(t) | |

| Inventory holding cost/units/time units | |

| Backlog cost/units/time units | |

| Repair cost | |

| Major maintenance cost | |

| Cost of defectives | |

| Cost of production per unit of produced parts | |

| Adjustment parameter for the rate of defectives |

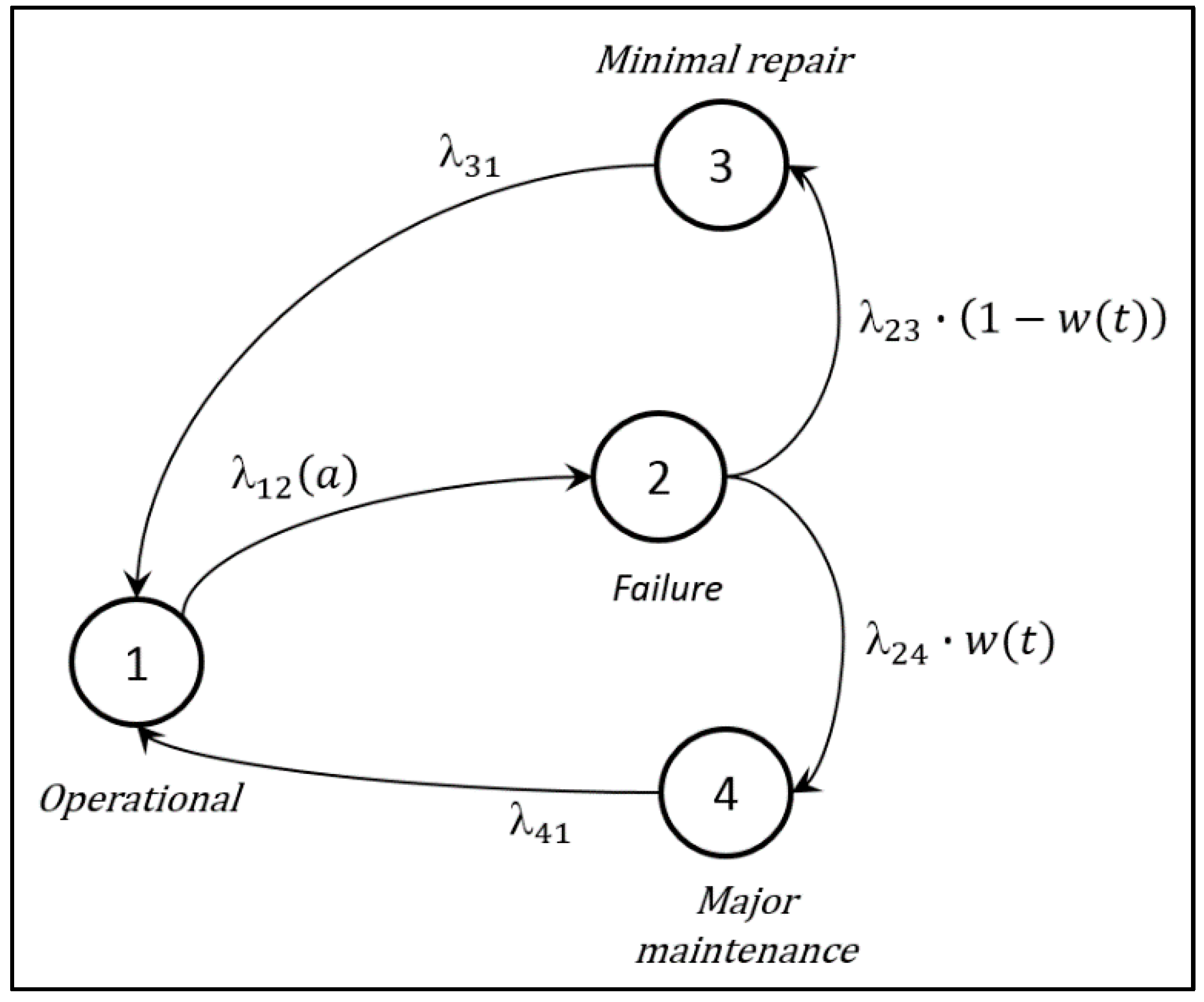

3.2. Problem Description

- A minimal and inexpensive repair that serves to operate the machine for a while, but with the disadvantage that it does not restore the effect of deterioration, it leaves the machine in as-bad-as-old conditions, ABAO.

- An expensive major maintenance, which mitigates completely the effects of deterioration, leaving the machine in as-good-as-new-conditions, AGAN.

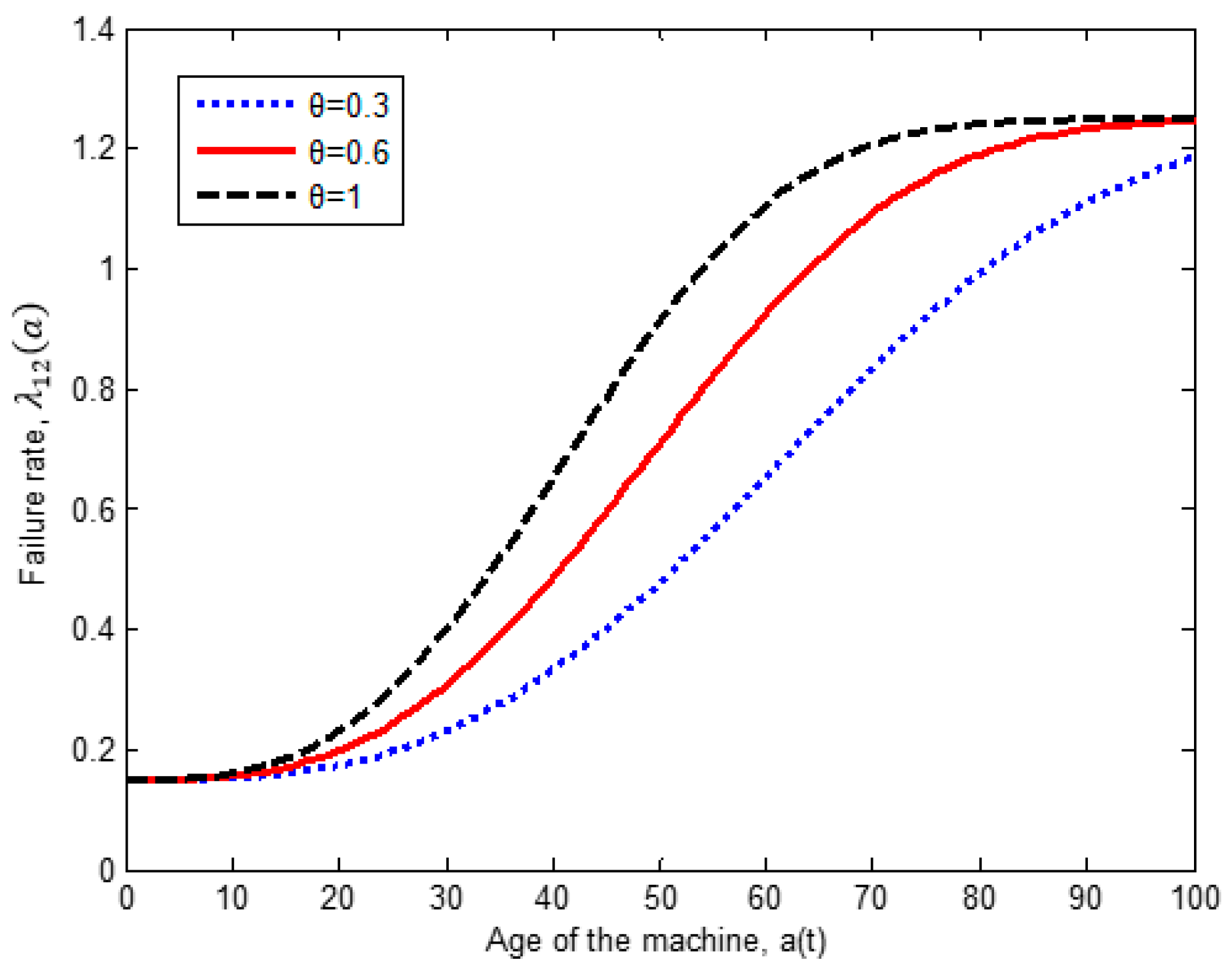

3.3. Problem Formulation

4. Optimization Method Description

5. Simulation and Numerical Results

5.1. Production Policy

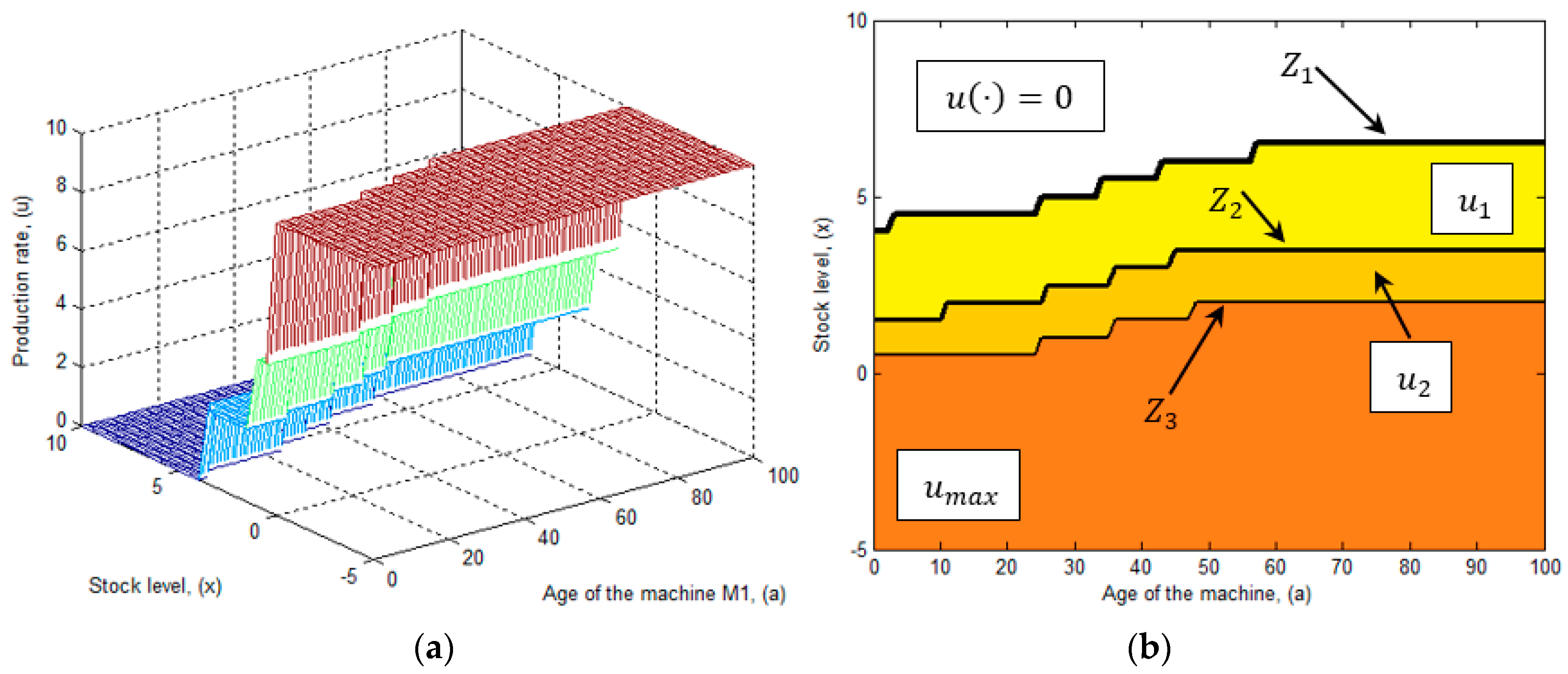

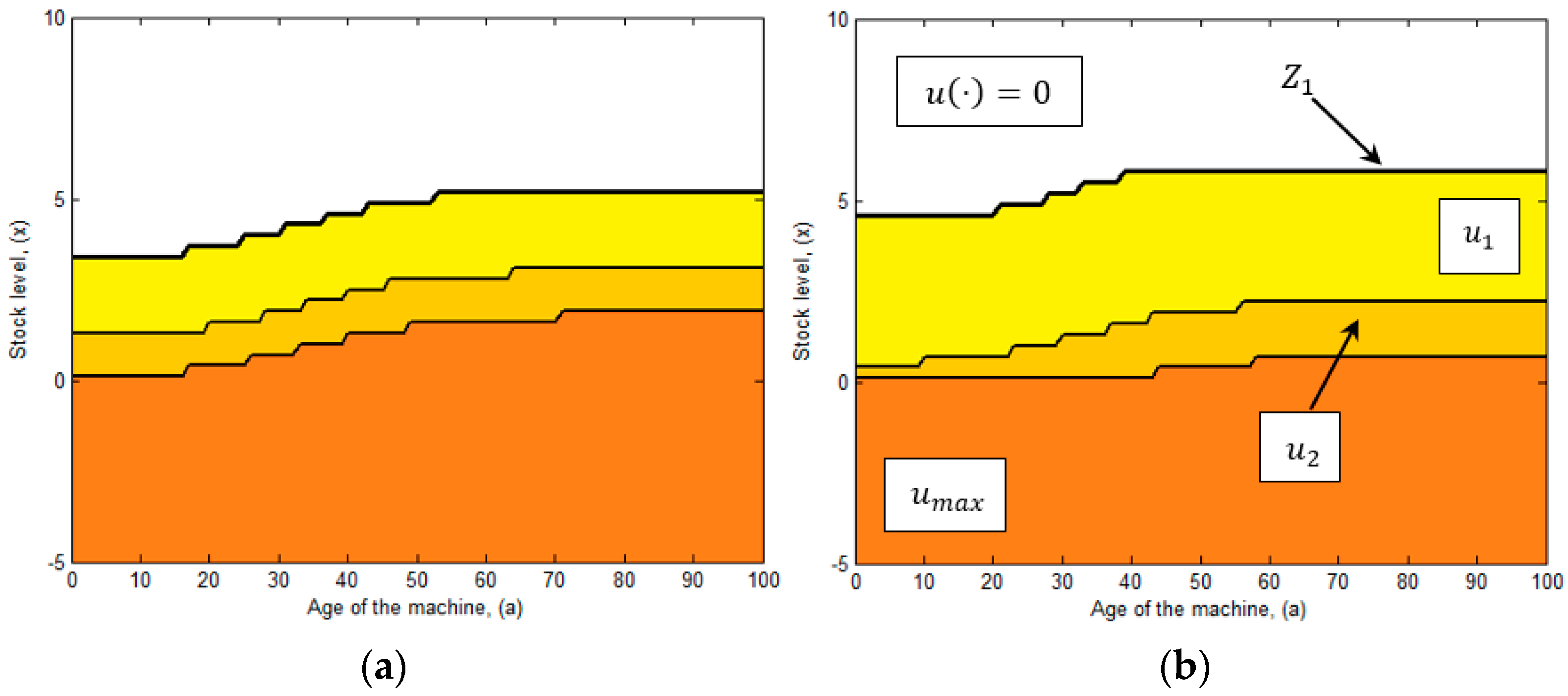

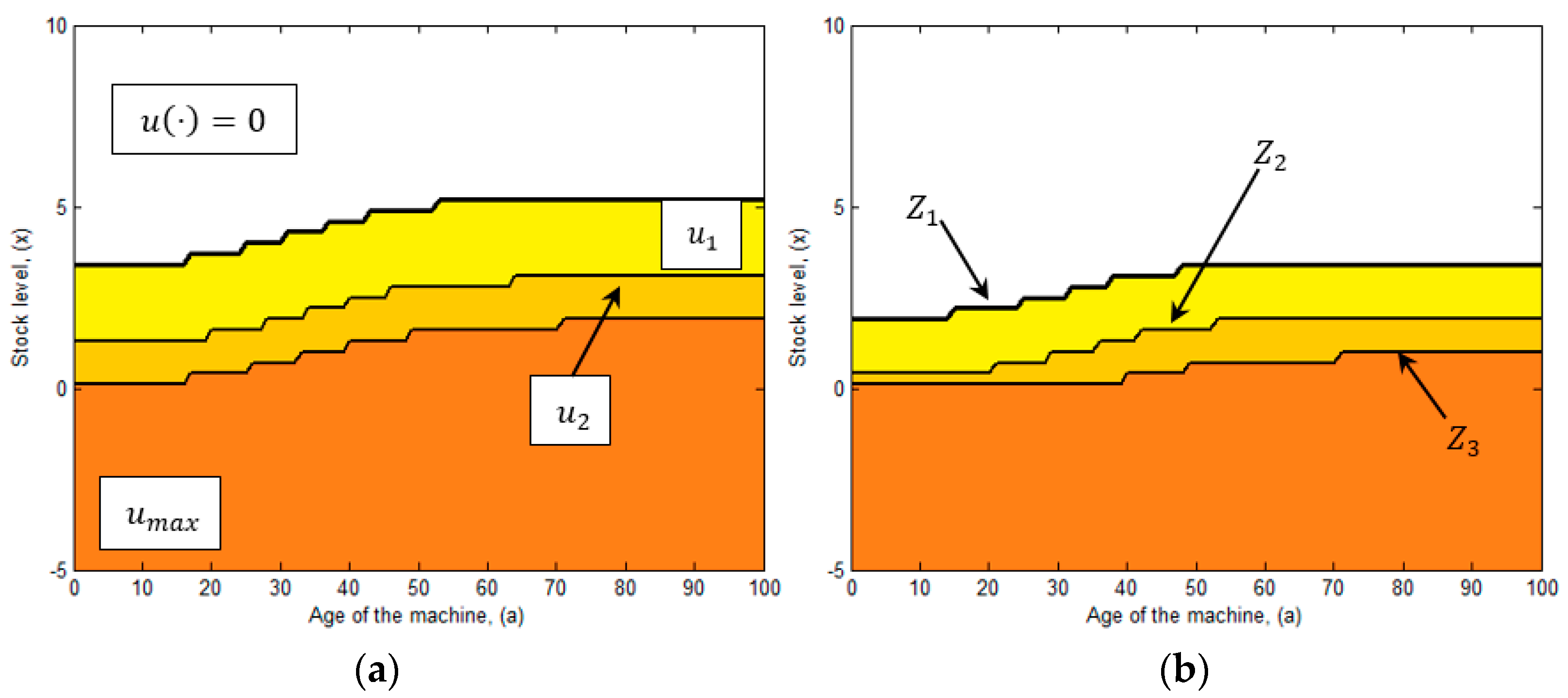

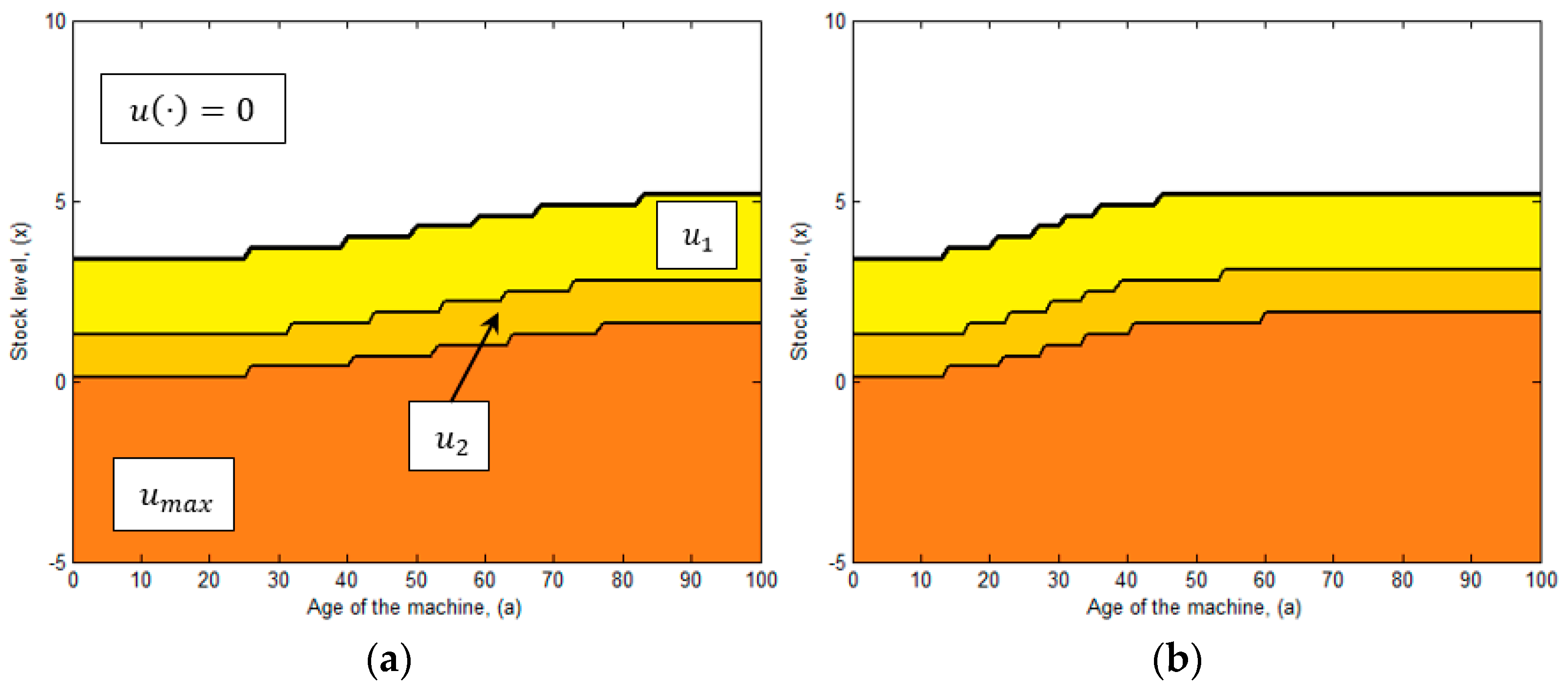

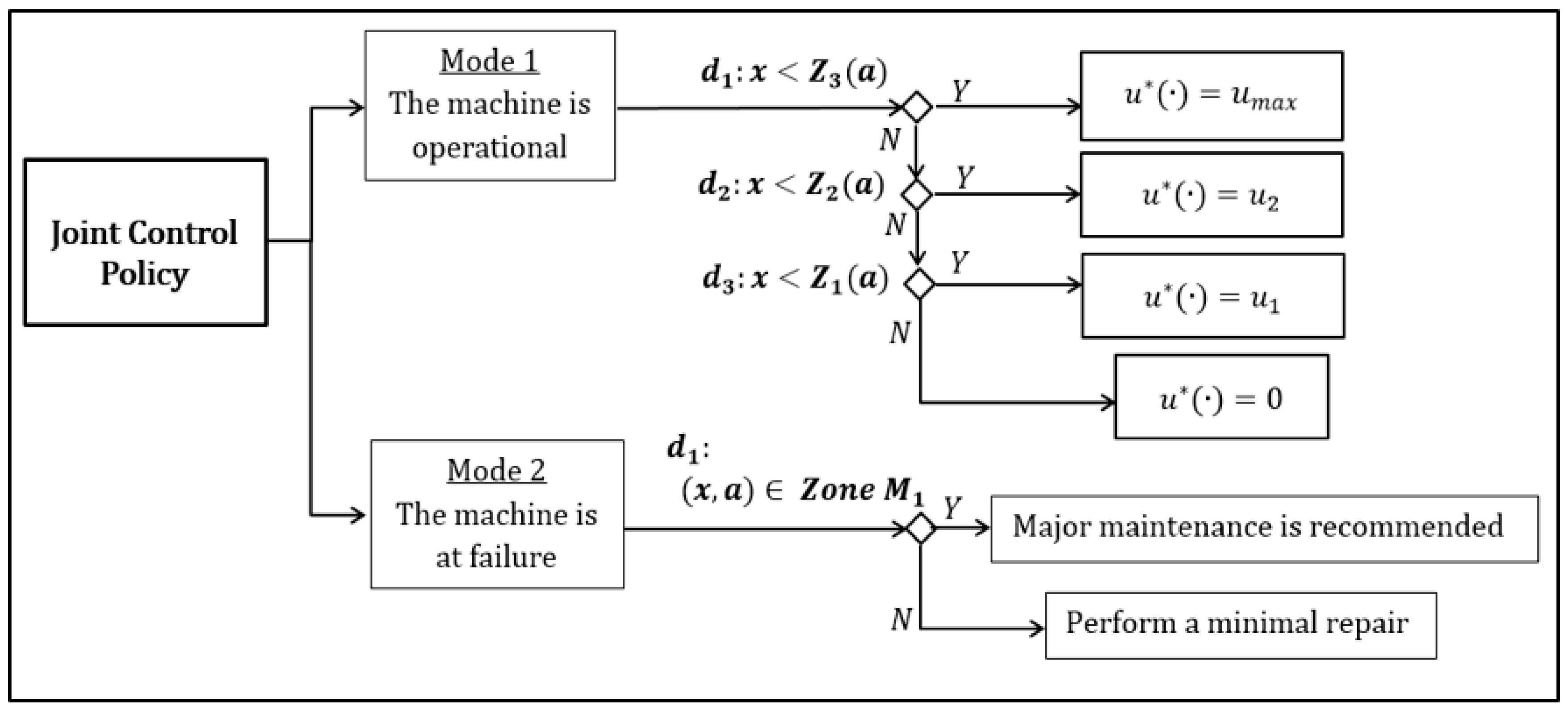

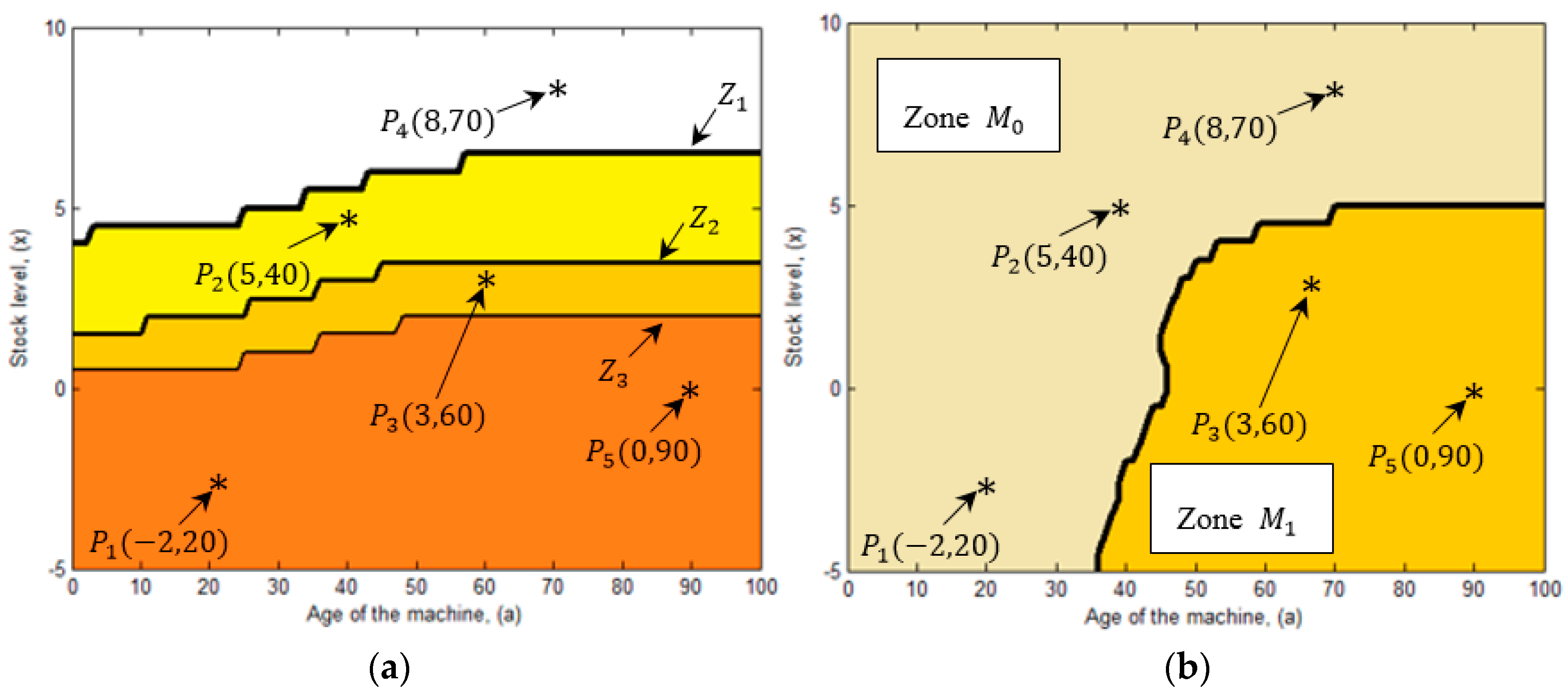

- The computational domain is divided in four zones, where the production rate is set to , or respectively. Such zones are delimited by the production thresholds , and .

- The production rate is decremented gradually (i.e., ) as the stock level increases and surpasses the production thresholds , and with . We note that the minimum production rate is recommended for high levels of inventory, when the stock level is between the production threshold and Since given the existence of inventory, the system can manage to satisfy product demand operating at a reduced pace and mainly because it avoids further deterioration. Moreover, we note that as the stock level decreases, the production rate increases, thus the machine operates at its second production rate when the inventory level is between the thresholds and , with the aim to replace inventory faster. Additionally, we note that the use of the maximum production rate is limited, because it deteriorates more rapidly than the machine, and so its use is only recommended in scenarios where the stock level is almost depleted and there is a need to rapidly replace the inventory level and avoid further shortages.

- From the obtained results we observe that the production thresholds and increases as the machine ages, this reflects the impact of the deterioration process on the production control rule. For instance at age , the production threshold has a value of , and as the machine deteriorates, at age , such threshold increases to . The same pattern is observed for thresholds and . The increment is explained by the fact that as the machine deteriorates, it produces more defectives and also it is subject to experience more frequent failures. Thus, more inventory is needed as protection to mitigate shortages.

- Decrease the production rate to zero, if the current stock level is above the first production threshold .

- Set the production rate to its first productivity , when the current stock level is under the first production threshold .

- Increase the production rate to its second productivity , when the stock level is below the second production threshold .

- Increase the production rate to its maximum rate , when the current stock level is under the third production threshold .

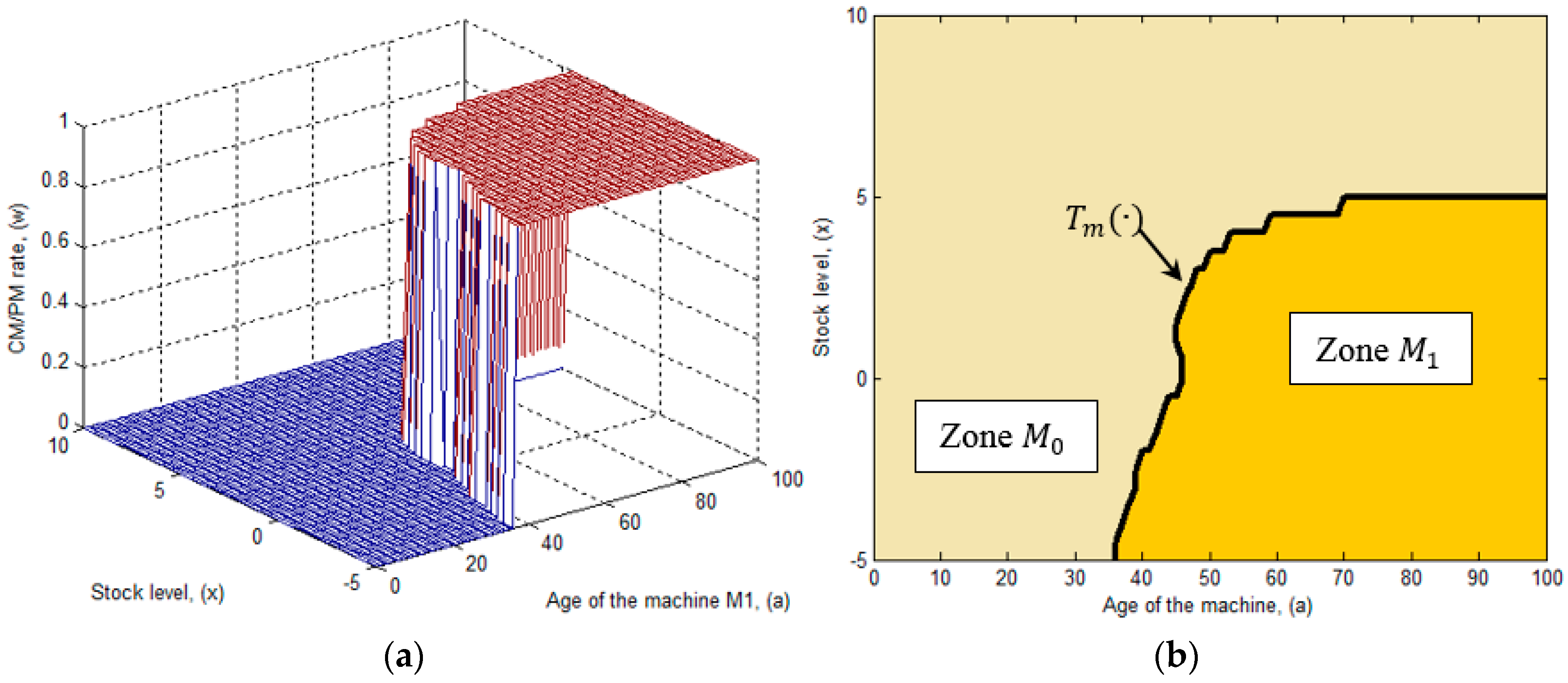

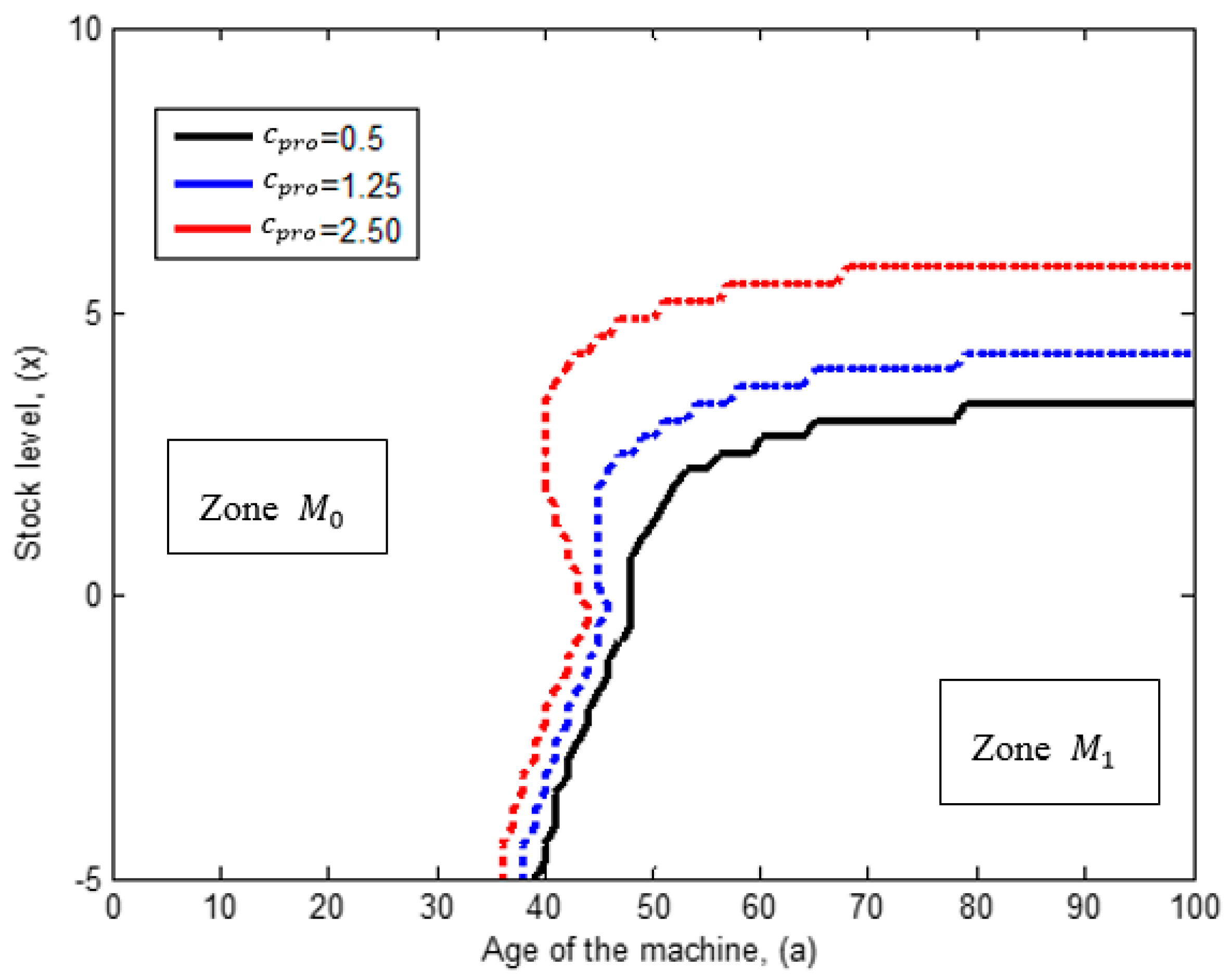

5.2. Repair/Major Maintenance Switching Policy

- When = 1, the variable is set to its maximum value, and it denotes the conduction of a major maintenance that completely mitigates the effects of the deterioration process, in this case reducing the failure intensity and the generation of defective units to initial conditions.

- When , the variable is set to its minimum value, indicating that a minimal repair must be performed. This type of maintenance does not restore the machine, since it leaves it the level of deterioration in the same level before the conduction of the repair.

- Zone : this zone suggests the conduction of a minimal repair, hence the decision variable , is set to its minimum value, = 0.

- Zone in this zone the recommendation is to conduct a major maintenance, since given the level of deterioration of the machine is not profitable its operation. Thus is set to its maximum value, = 1.

6. Sensitivity and Results Analysis

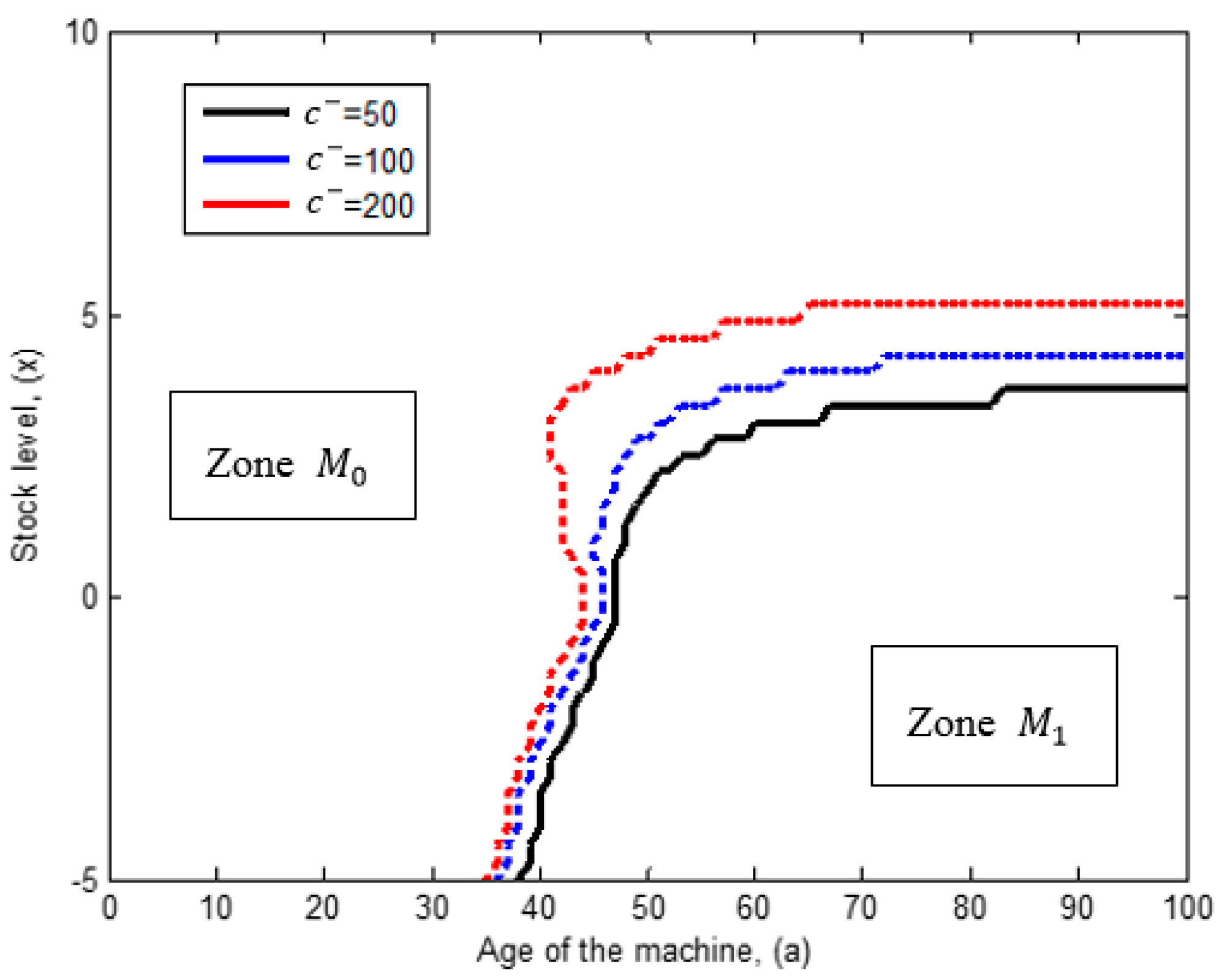

6.1. Influence of the Backlog Cost

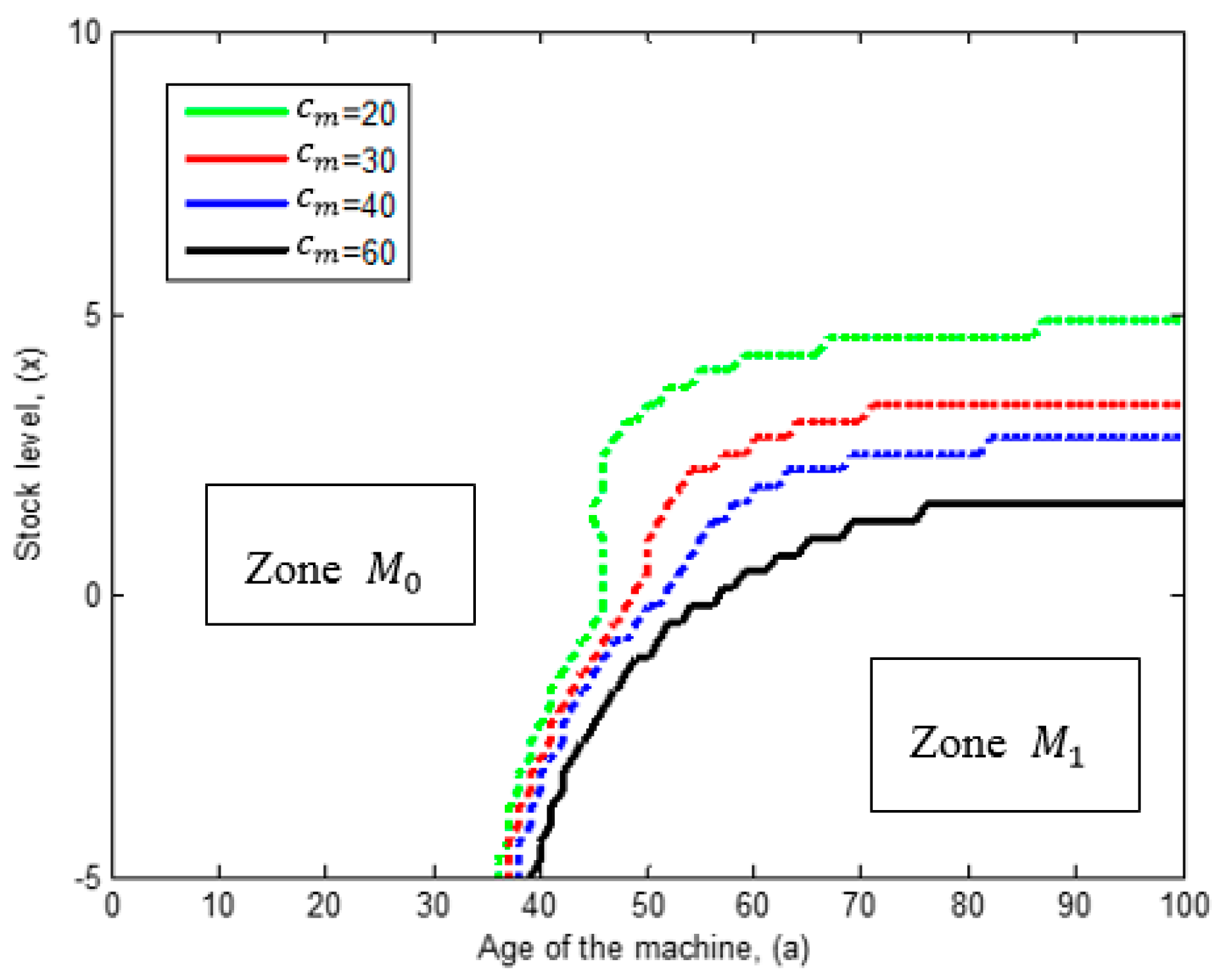

6.2. Influence of the Major Maintenance Cost

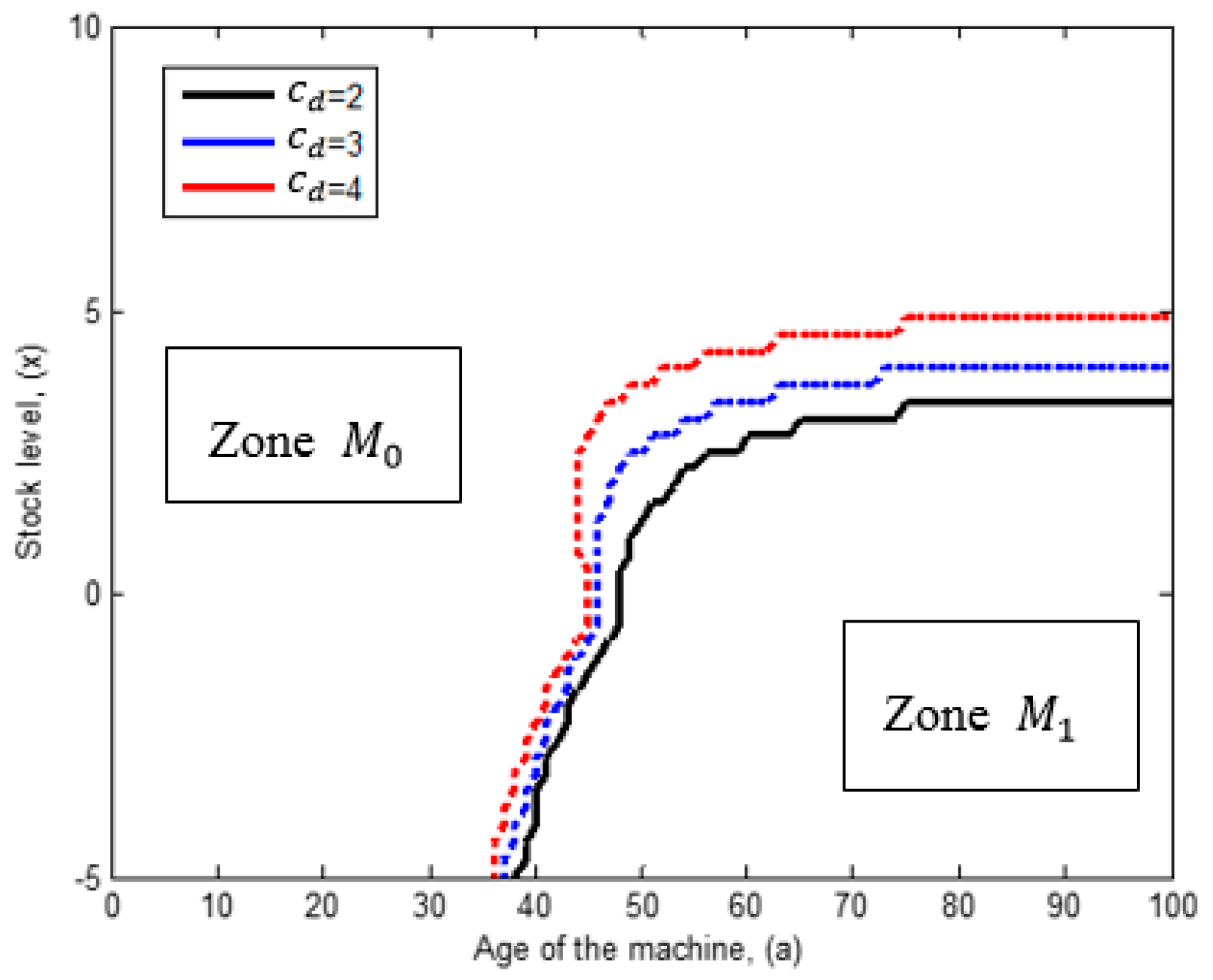

6.3. Influence of the Defectives Cost

6.4. Influence of the Production Cost

6.5. Influence of the Pace of the Failure Rate

7. Comparative Study

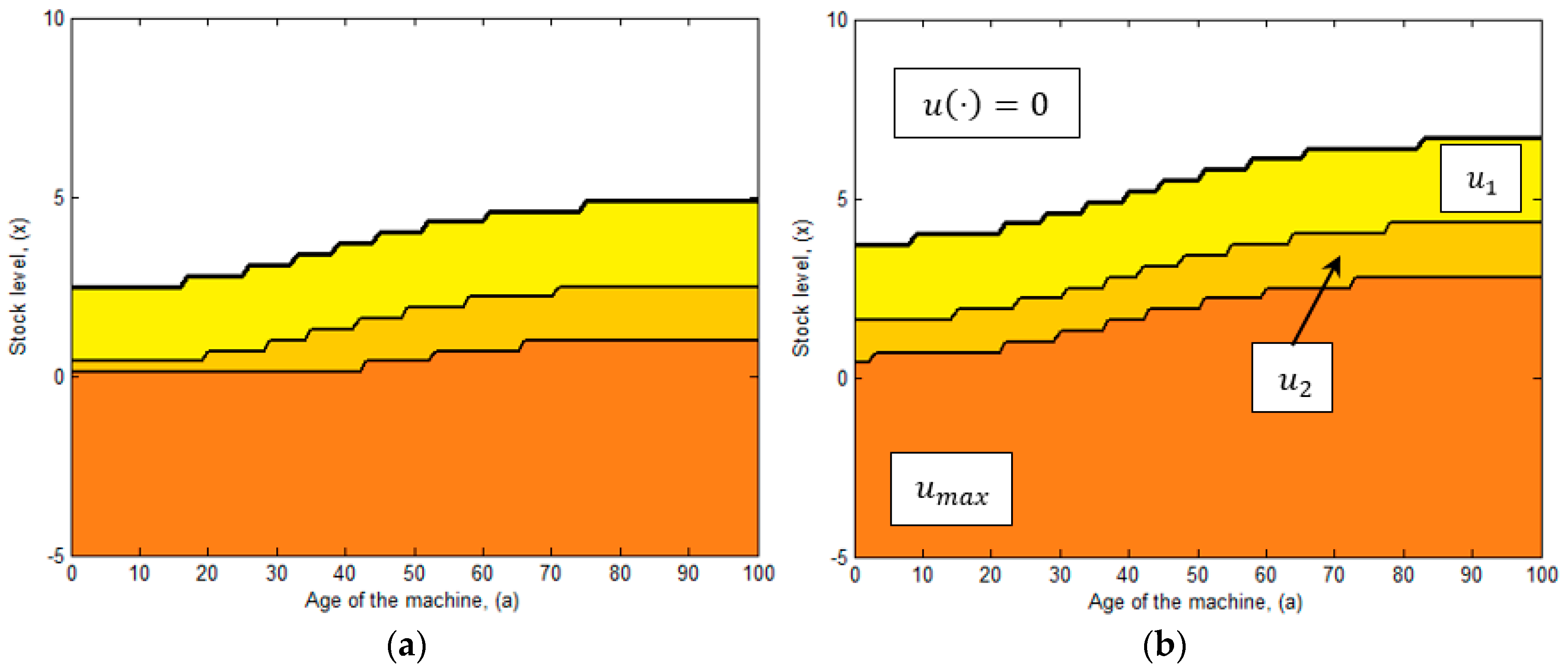

- Policy-I: defines the production scenario (basic case) of the joint control policy obtained in Section 5, where the production and maintenance policies are determined simultaneously in an integrated model. The particularity of Policy-I is that the production threshold is dynamic, it is adjusted progressively in function of the level of deterioration of the machine, and major maintenance can be once the machine has reached a certain level of deterioration that justifies the cost of such type of maintenance. Thus, the conduction of major maintenance has a feedback on the level of deterioration of the machine.

- Policy-II: this policy is derived from the previous policy with the difference that the production threshold is not adjusted progressively, it remains constant at a given level for all the considered time interval and it does not evolve in function of the deterioration of the machine. Nevertheless, the conduction of major maintenance can be conducted based on a feedback with the deterioration of the machine as in Policy-I.

- Policy-III: the production threshold is dynamic and it is adjusted in function of the deterioration of the machine as in Policy I. However, major maintenance is conducted only when the machine has reached its maximum age limit.

8. Managerial Implication

9. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liberopoulos, G.; Papadopoulos, C.T.; Tan, B.; Smith, J.M.; Gershwin, S.B. Stochastic Modeling of Manufacturing Systems, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 3–363. ISBN 978-3-540-26579-5. [Google Scholar]

- Colledani, M.; Tolio, T. Integrated analysis of quality and production logistics performance in manufacturing lines. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 485–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedes, Y.; Chelbi, A.; Rezg, N. Quasi-optimal integrated production, inventory and maintenance policies for a single-vendor single-buyer system with imperfect production process. J. Intell. Manuf. 2012, 24, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Gómez, H.; Gharbi, A.; Kenné, J.P.; Montaño-Arango, O.; Hernández-Gress, E.S. Production control problem integrating overhaul and subcontracting strategies for a quality deteriorating manufacturing system. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhada, F.Z.; Ouzineb, M.; Pellerin, R.; El-Hallaoui, I. Multilevel hybrid method for optimal buffer sizing and inspection stations positioning. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouslah, B.; Gharbi, A.; Pellerin, R. Joint economic design of production, continuous sampling inspection and preventive maintenance of a deteriorating production system. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 173, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midfal, I.; Hajej, Z.; Dellagi, S. Production/Maintenance Control of Multiple-Product Manufacturing System. In Proceedings of the Second World Conference on Complex Systems, Agadir, Morocco, 10–12 Novenber 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatab, A.; Ait-Kadi, D.; Rezg, N. Availability optimization for stochastic degrading systems under imperfect preventive maintenance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 4132–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajej, Z.; Turki, S.; Rezg, N. Modelling and analysis for sequentially optimizing production, maintenance and delivery activities taking into account product returns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 4694–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askri, T.; Hajej, Z.; Rezg, N. Jointly production and correlated maintenance optimization for parallel leased machines. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, F. Manufacturing systems with a production dependent failure rate: Structure of optimality. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2010, 55, 2401–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahane, M.; Rezg, N.; Chelbi, A. Optimal production plan for a multi-products manufacturing system with production rate dependent failure rate. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 3517–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoues, M.; Dahane, M.; Mouss, K.N.; Rezg, N. Production planning in integrating maintenance context for multi-period multi-product failure-prone single-machine. In Proceedings of the 18th IEEE Conference on Emerging Technologies & Factory Automation, Cagliari, Italy, 10–13 September 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouedeu, A.F.; Kenné, J.P.; Dejax, P.; Songmene, V.; Polotski, V. Production and maintenance planning for a failure-prone deteriorating manufacturing system: A hierarchical control approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 76, 1607–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong-Ping, S. Optimal Control and Optimization of Stochastic Supply Chain Systems, 1st ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2013; pp. 2–272. ISBN 978-1-4471-4724-4. [Google Scholar]

- Love, C.E.; Zhang, Z.G.; Zitron, M.A.; Guo, R. A discrete semi-Markov decision model to determine the optimal repair/replacement policy under general repairs. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 125, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershwin, S.B. Manufacturing System Engineering, 1st ed.; PTR Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 1–501. ISBN 013560608X. [Google Scholar]

- Hlioui, R.; Gharbi, A.; Hajji, A. Replenishment, production and quality control strategies in three-stage supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 166, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, H.J.; Dupuis, P.G. Numerical Methods for Stochastic Control Problems in Continuous Time, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 2–475. ISBN 978-0-387-95139-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gharbi, A.; Hajji, A.; Dhouib, K. Production rate control of an unreliable manufacturing cell with adjustable capacity. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 6539–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehayem-Nodem, F.I.; Kenné, J.P.; Gharbi, A. Simultaneous control of production, repair/replacement and preventive maintenance of deteriorating manufacturing systems. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 134, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, A.; Gharbi, A.; Kenné, J.P.; Pellerin, R. Production control and replenishment strategy with multiple suppliers. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 208, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenné, J.P.; Dejax, P.; Gharbi, A. Production planning of a hybrid manufacturing-remanufacturing system under uncertainty within a closed-loop supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershwin, S.B. Design and operation of manufacturing systems: The control point policy. IIE Trans. 2000, 32, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, M.; Kenneth, R.S.; Candace, A.Y. Deux chemicals inc. goes just-in time. Interfaces 2009, 39, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 10 | 4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.5 | 5 | 0.15 | 0 | 0.2160 |

| r | |||||||||

| 1.1 | 120 | 120 | 5 | 4 | 0.6 | 1 | 3 | 0.7290 | −15 × 10−6.2 |

| 1 | 150 | 5 | 20 | 3 | 0.5 |

| Scenario | Production Threshold | Major Maintenance | Optimal Total Cost | Cost Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy-I (basic case) | dynamic | feedback with deterioration | 83.16 | - |

| Policy-II | constant | feedback with deterioration | 97.96 | 17.79% |

| Policy-III | dynamic | conducted at the age limit | 113.40 | 36.36% |

| Point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| 0 | ||||

| 1 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivera-Gómez, H.; Montaño-Arango, O.; Corona-Armenta, J.R.; Garnica-González, J.; Hernández-Gress, E.S.; Barragán-Vite, I. Production and Maintenance Planning for a Deteriorating System with Operation-Dependent Defectives. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8020165

Rivera-Gómez H, Montaño-Arango O, Corona-Armenta JR, Garnica-González J, Hernández-Gress ES, Barragán-Vite I. Production and Maintenance Planning for a Deteriorating System with Operation-Dependent Defectives. Applied Sciences. 2018; 8(2):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8020165

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivera-Gómez, Héctor, Oscar Montaño-Arango, José Ramón Corona-Armenta, Jaime Garnica-González, Eva Selene Hernández-Gress, and Irving Barragán-Vite. 2018. "Production and Maintenance Planning for a Deteriorating System with Operation-Dependent Defectives" Applied Sciences 8, no. 2: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8020165