Pratyabhijñā Apoha Theory, Shannon–Weaver Information, Saussurean Structure, and Peircean Interpretant Agency

Abstract

:- A “bit” of information is definable as a difference which makes a difference.

- Gregory Bateson (1972), Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 315

- We praise Śiva who, through his own intention [icchā], with the chisel of semantic exclusion [apohana], divides entities that are a compact mass not different from his own nature [and thereby] creates diverse forms.

1. Introduction

2. The Philosophical Reenactment of Nondual Śaiva Myth and Ritual

3. The Buddhist Theory of Apoha

4. The Śaivas, like the Realists, Accept Apoha as an Important Feature of Vikalpa

When a pot is seen, it is also possible that there could be, in the place of the pot, a non-pot, such as a cloth, etc. [Such a non-pot would like the pot also] naturally have a location believed to be suitable; it would produce cognition [of itself as object], and would be brought to its location by its own causes.8 Since the manifestations of both the pot and the non-pot are possible, there is an opportunity for a superimposition [in which one wrongly takes a pot to be a non-pot]. Since there is the [possibility of the] superimposition of a non-pot, there is the operation of exclusion, which is characterized by negation. Thus the ascertainment [niścaya] “pot” has the nature of conceptual construction that is animated by that [exclusion].(IPV 1.6.2, vol. 1, p. 306)9

5. Cosmic Role of the Exclusion Śakti

In the condition without conceptual construction [avikalpa], the pot has the essential nature of consciousness [cit], and just like consciousness [cit], has the nature of everything [viśvaśarīra] and is perfect [pūrna]. However, there is no worldly activity with that [pot that has the nature of everything and is perfect]. Therefore, [the knower], manifesting the operation of Māyā, causes the thing, even though perfect [pūrna], to be fragmented. By means of that, is created semantic exclusion [apohana], having the form of negation of the non-pot, such as the self, cloth, and so on. On the basis of that very exclusion [vyapohana], there is said to be the ascertainment [niścaya] of the pot. The meaning of “only” [eva] in [the ascertainment] “only the pot” is the negation of other things that are supposed to be possible. Therefore, there is this complete distinction, by distinction all around, like cutting.(IPV 1.6.3, vol. 1, pp. 309–10)13

6. Overcoding with Chief Frameworks of Recognition and Agency

Since the Buddhists cannot even account for exclusion, because of their understanding of cognition as an evanescent phenomenal stream, it would be impossible for them to posit that as the sole basis of reference.There may be this doubt: The pot is perceived as confined to its own form. How can a conceptual construction [vikalpa], as pertaining to the cognition of the pot, effect the negation of the non-pot? For not even the name of non-pot has been apprehended by anyone. How can the mental impression of the non-pot be awakened when the pot is seen? [This reasoning is accepted by the Śaivas:] True. [However,] the Buddhist is to be censured in this way, and not us.(IPV 1.6.3, vol. 1, p. 308)14

The determinate ascertainment [niścaya] of “that” results from the exclusion of the “not-that” by the knower who experiences the semantic intuition [pratibhā] of both the “that” and the “not-that.” This [determinate ascertainment] is explained to be conceptual construction [vikalpa] [as is expressed]: “This is a ‘pot’”.(IPK 1.6.3, vol. 1, p. 309)15

I point out that the Pratyabhijñā philosophers have not only made the common argument that a negation relies upon recognitions of the similar things to be negated, but have rather paradoxically explained that difference is a kind of recognized similarity.17That is the knower’s mnemonic impression [saṃskāra] of the previous experience by which the previous experience persists even at the time of semantic exclusion [apohana].(quoted at IPV 2.2.3, vol. 2, p. 45)16

One of the main themes of the chapter on apoha is that in its highest nature the Lord’s self-recognition that generates exclusion is ultimately unfragmented or nondual,19 a “transcendental synthesis of fragmentation”. Through the proper understanding of this one comes to participate in it.20Here, it has been demonstrated that what is called the knower [pramātṛ] is different than the means of knowledge [pramāṇa], and to be an autonomous [svantantra] agent [kartṛ] with respect to cognitions [pramā] by bringing about their conjunction and disjunction. There is the manifestation [avabhāsa] of all objects within the knower [pramātṛ].(IPV 1.6.3, vol. 1, p. 309)18

7. Information as Differentiation from Entropy and the Development of Systematic Sign Usage

Bit is actually a technical term for “binary digit” (Pierce 1980, p. 98).provides, in the bit, a universal measure of an amount of information in terms of choice or uncertainty. Specifying or learning the choice between equally probable alternatives, which might be messages or numbers to be transmitted, involves one bit of information.

This passage, which quotes the Pāṇiṇian definition of the karma, is closely followed by Utpaladeva’s statement of the idealistic and pragmatic significance of the kāraka:The denotation of the referent is also by means of joint absence, like, for instance, [the technical term] karman denotes what the agent (kartuḥ) most wants to obtain (īpstamam) [by his action].(Pramāṇasamuccayavṛtti V. 54 in Dignāga 2015, p. 147)

From the Śaiva perspective, Dignāga should have more greatly attended to the idealistic and pragmatic context of the direct object described above.Otherness of the Self does not result from the differentiation of the recognitive apprehension [parāmarśa] of the condition of “I”, and so on, because there is the creation of it only as the object of the recognitive apprehension of I [ahammṛśyatā], like the direct object [karman] expressed by the conjugational ending [tiṅ].(IPK 1.5.17)

Moreover, substantiating the Pratyabhijña’s transindividual first-person, agent-centered syntax as well as cognitive science accounts of the religious detection of, and conversion as acquiescing to, a higher executive agency (Boyer 2001; McNamara 2014), the biosemiotician Hoffmeyer has argued that in both physical and cultural evolution there is evidence of a natural teleology towards what he calls “semiotic freedom”: more semantically rich and practically efficacious interpretations of the world (Hoffmeyer 2008a, 2010b)..

(From Apel 1994, p. 238)

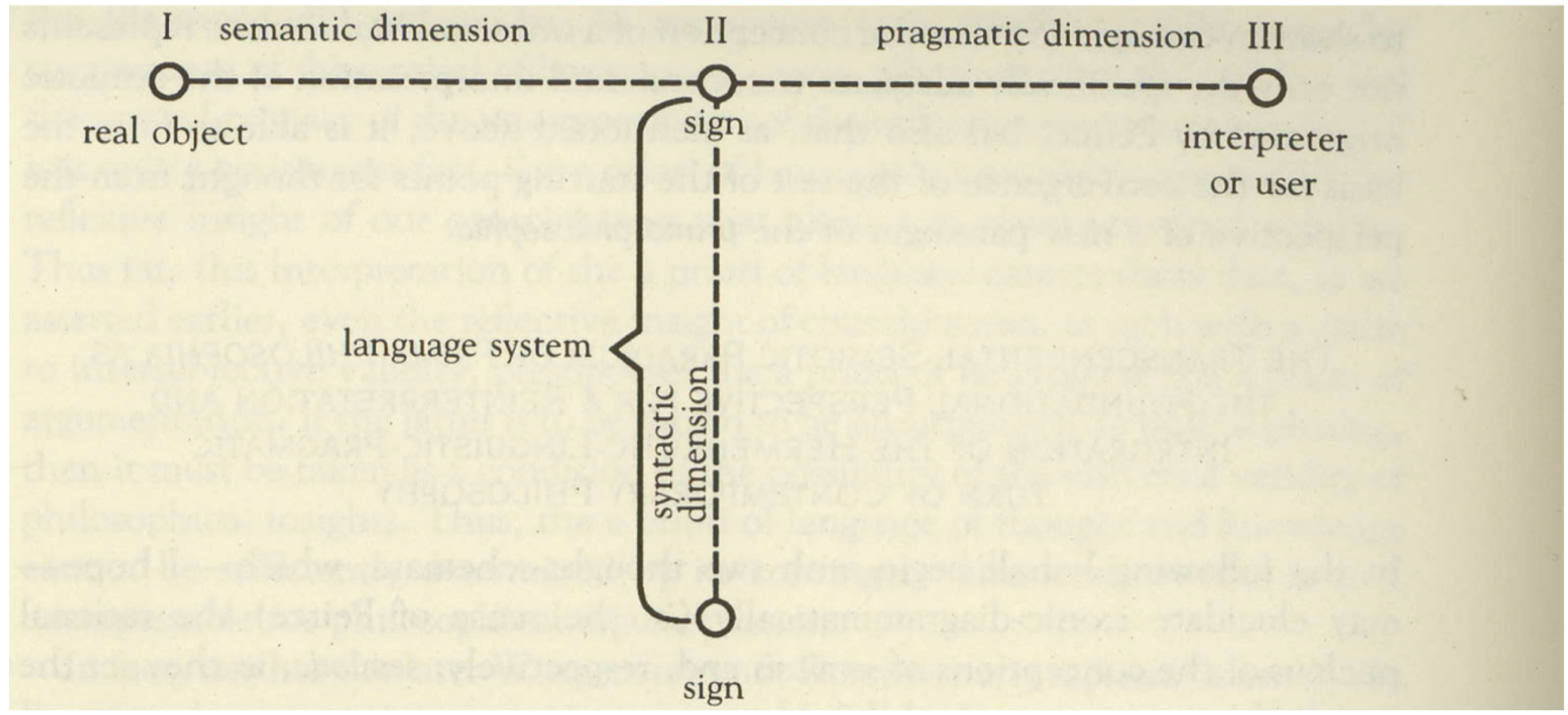

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIPV | Bhāskarakaṇṭha’s commentary Bhāskarī on the IPV |

| IPK | Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā by Utpaladeva, for convenience cited in edition with BIPV and IPV, rather than the better edition of Torella |

| IPV | Īśvarapratyabhijñāvimarśinī by Abhinavagupta, commentary on IPK, cited in edition with BIPV |

| IPVV | Īśvarapratyabhijñāvivṛtivimarśinī by Abhinavagupta, commentary on Utpaladeva’s now fragmentary Īśvarapratyabhijñāvivṛti |

Bibliography

Abhinavagupta. 1989. A Trident of Wisdom: Translation of Parātrīśikā-Vivaraṇa. Edited and Translated by Jaideva Singh. Albany: State University of New York Press.Aristotle, and Thomas Aquinas. 1961. Commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics. Translated by John P. Rowan. Notre Dame: Dumb Ox Books.Bhartṛhari. 1963–1973. Vākyapadīya (with Commentaries). 4 vols. Edited by K. A. Subramania Iyer. Kāṇḍa 1, Pune: Deccan College, 1966. Kāṇḍa 2, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1983. Kāṇḍa 3, part 1, Pune: Deccan College, 1963. Kāṇḍa 3, part 2, Pune: Deccan College, 1973.Brier, Soren, ed. 2003. Thomas Sebeok and the Biosemiotic Legacy. Cybernetics and Human Knowing: A Journal of Second-Order Cybernetics, Autopoiesis and Cyber-Semiotics 10: 5–111.Brier, Soren. 2008. Cybersemiotics: Why Information Is Not Enough! Toronto: University of Toronto Press.Capra, Fritjof, and Pier Luigi Luisi. 2014. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Davies, Paul, and Niels Henrik Gregersen, eds. 2010. Information and the Nature of Reality: From Physics to Metaphysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Deacon, Terrence. 1997. The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language and the Brain. New York: Norton.Deacon, Terrence, and Tyrone Cashman. 2009. The Role of the Symbolic Capacity in the Origins of Religion. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 3: 1–28.Dennett, Daniel C. 2013. Aching Voids and Making Voids: A Review of Incomplete Nature: How Mind Emerged from Matter. Quarterly Review of Biology 88: 321–24.Dharmakīrti, and Manorathanandin. 1984. Pramāṇavārttika of Acharya Dharmakirtti with the Commentary ‘Vritti’ of Acharya Manorathanandin. Edited by Dwarikadas Shastri. Varanasi: Bauddha Bharati.Dharmakīrti, and Prajñākaragupta. 1991. Pramāṇavārttika of Dharmakīrti with the Vārtiikālañkara of Prajñākaragupta. 2 vols (incomplete). Edited with Hindi commentary by Swami Yogindrananda. Varanasi: Saddarsana Prakasan Sansthan.Dreyfus, Georges B. J. 1997. Recognizing Reality: Dharmakīrti’s Philosophy and Its Tibetan Interpretations. Albany: State University of New York Press.Ganeri, Jonardon. 2011. Artha: Testimony and the Theory of Meaning in Indian Philosophical Analysis. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.Gibson, James J. 2015. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Psychology Press.Hayes, Richard P. 1988. Dignāga on the Interpretation of Signs. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.Hoffmeyer, Jesper. 1997. Signs of Meaning in the Universe. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.Hoffmeyer, Jesper, ed. 2008b. A Legacy for Living Systems: Gregory Bateson as Precursor to Biosemiotics. Dordrecht: Springer.Hoffmeyer, Jesper. 2010a. God and the World of Signs: Semiotics and the Emergence of Life. Zygon 45: 367–90.Kaviraj, Gopinath. 1966. The Doctrine of Pratibhā in Indian Philosophy. In Aspects of Indian Thought. Burdwan: University of Burdwan.Kuanpoonpol, Priyawat. 1991. Pratibhā: The Concept of Intuition in the Philosophy of Abhinavagupta. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.Kull, Kalevi. 2014. Zoosemiotics is the Study of Animal Forms of Knowing. Semiotica 198: 47–60.Lawrence, David Peter. 1998. The Mythico-Ritual Syntax of Omnipotence. Philosophy East and West 48: 592–622.Lawrence, David Peter. 2009. Proof of a Sentient Knower: Utpaladeva’s Ajaḍapramātṛsiddhi with the Vṛtti of Harabhatta Shastri. Journal of Indian Philosophy 37: 627–53.Lawrence, David Peter. 2011. Current Approaches: Hindu Philosophical Traditions. In Continuum Companion to Hindu Studies. Edited by Jessica Frazier. London: Continuum, pp. 137–51.Lawrence, David Peter. 2013a. The Disclosure of Śakti in Aesthetics: Remarks on the Relation of Abhinagupta’s Poetics and Nondual Kashmiri Śaivism. Southeast Review of Asian Studies 35: 90–102.Lawrence, David Peter. 2018. Pratyabhijñā Philosophy and the Evolution of Consciousness: Religious Metaphysics, Biosemiotics and Cognitive Science. In Tantrapuspanjali: Tantric Traditions and Philosophy of Kashmir (Studies in Memory of Pandit H.N. Chakravarty). Edited by Bettina Sharada Baumer and Hamsa Stainton. Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts.Logan, Robert K. 2014. What Is Information: Propogating Organization in the Bioshere, Symbolosphere, Technosphere and Econosphere. Foreword by Terrence Deacon. Toronto: Design Emergence Media Organization.Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1991. Questions Concerning Certain Faculties Claimed for Man. In Peirce on Signs. Edited by James Hooper. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 34–53.Prueitt, Catherine. 2017a. Shifting Concepts: The Realignment of Dharmakīrti on Concepts and the Error of Subject/Object Duality in Pratyabhijñā Śaiva Thought. The Journal of Indian Philosophy 45: 21–47.Prueitt, Catherine. 2017b. Karmic Imprints, Exclusion, and the Creation of the Worlds of Conventional Awareness in Dharmakīrti’s Thought. Sophia, 1–23.Ratie, Isabelle. 2011. Le Soi et l’Autre: Identite, Difference et alterite dans la philosophie de la Pratyabhijna. Leiden: Brill.Sanderson, Alexis. 1988. Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions. In The World’s Religions. Edited by Stewart Sutherland, Leslie Houlden, Peter Clarke, and Friedhelm Hardy. London: Routledge, pp. 660–704.Saussure, Ferdinand de. 1992. Course in General Linguistics. Translated by Roy Harris. La Salle: Open Court.Sebeok, Thomas A. 2001. Global Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.Sherman, Jeremy. 2017. Neither Ghost Nor Machine: The Emergence and Nature of Selves. Foreward by Terrence Deacon. New York: Columbia University Press.Singer, Milton. 1984. Man’s Glassy Essence: Explorations in Semiotic Anthropology. Bloomington: Indian University Press.Torella, Raffaele. 2007. Studies in Utpaladeva’s Īśvarapratyabhijñā-vivṛti, Part I: Apoha and Anupalabdhi in a Śaiva Garb. In Expanding and Merging Horizons: Contributions to South Asian and Cross-Cultural Studies in Commemoration of Wilhelm Halbfass. Edited by Karin Preisendanz. Vienna: Osterreichische Akadamie der Wissenschaften, pp. 473–90.Utpaladeva. 2002. The Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā of Utpaladeva with the Author’s Vṛtti, corrected edition. Edited and Translated by Raffaele Torella. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.Varela, Francisco J., Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. 2001. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Cambridge: MIT Press.References

- Abhinavagupta. 1986–1998. Īśvarapratyabhijñāvimarśinī (with Bhāskarī). Edited by K. A. Subramania Iyer and K. C. Pandey. Translated by K. C. Pandey. Edition is Vols. 1–2, volume 3 is English Translation. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Apel, Karl Otto. 1994. Karl Otto Apel: Selected Essays, Volume One: Towards a Transcendental Semiotics. Edited by Eduardo Mendieta. Atlantic Highlands: Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, W. Ross. 1962. Principles of the Self-Organizing System. In Principles of Self-Organization: Transactions of the University of Illinois Symposium. Edited by H. Von Foerster and G. W. Zopf. London: Pergamon Press, pp. 255–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, Gregory. 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantyne Books, pp. 101–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baumer, Bettina. 2011. The Three Grammatical Persons and the Trika. In Abhinavagupta’s Hermeneutics of the Absolute, Anuttaraprakriyā: An Interpretation of His Parātrīśikā Vivaraṇa. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, pp. 101–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bergson, Henri. 1911. Creative Evolution. Translated by Arthur Mitchell. New York: Henry Holt and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, Ludwig von. 1972. The History and Status of General Systems Theory. Academy of Management Journal 15: 407–26. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, Pascal. 2001. Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kenneth. 1945. A Grammar of Motives. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kenneth. 1989. On Symbols and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Amita. 2011. Funes and Categorization in an Abstraction-Free World. In Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. Edited by Mark Siderits, Tom J. F. Tillemans and Arindam Chakrabarti. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 247–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, Edward. 1984. The Conception of Language and the Use of Paradox in Buddhism and Taoism. Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 375–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Tzu. 1964. Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings. Translated by Burton Watson. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coreth, Emerich. 1968. Metaphysics. Translated by Joseph Donceel. New York: Herder & Herder. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, Mario. 2003. The Semiotics of Signlessness: A Buddhist Doctrine of Signs. Semiotica 147: 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, Terrence. 2007. Shannon-Boltzmann-Darwin: Redefining Information. Part 1. Cognitive Semiotics 1: 123–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, Terrence. 2008. Shannon-Boltzmann-Darwin: Redefining Information. Part 2. Cognitive Semiotics 2: 167–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, Terrence. 2010. What is Missing from Theories of Information? In Information and the Nature of Reality: From Physics to Metaphysics. Edited by Paul Davies and Niels Henrik Gregersen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 146–69. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon, Terrence. 2012. Incomplete Nature: How Mind Emerged from Matter. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1976. Of Grammatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dignāga. 2015. Dignāga’s Philosophy of Language: Pramānasamuccayavṛtti V on Anyāpoha. Edited and translated by Ole Holten Pind, with an Introduction by Ernst Steinkellner. Vienna: Verlag der Osterreichischien Akademie Wissenschaften, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus, Georges. 2011. Apoha as a Naturalized Account of Concept Formation. In Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. Edited by Mark Siderits, Tom Tillemans and Arindam Chakrabarti. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 207–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, John D. 2004. Foundations of Dharmakīrti’s Philosophy. Boston: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, John D. 2011. Key Features of Dharmakīrti’s Apoha Theory. In Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. Edited by Mark Siderits, Tom Tillemans and Arindam Chakrabarti. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 84–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuche, John R. 2001. Person to Person: Vivarana of Abhinavagupta on Parātriṃśikā Verses 3–4. Indo-Iranian Journal 44: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeri, Jonardon. 2008. Contextualism in the Study of Indian Intellectual Cultures. Journal of Indian Philosophy 36: 551–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1969. Identity and Difference. Translated with an introduction by Joan Stambaugh. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeyer, Jesper. 2008a. Biosemiotics: An Examination into the Signs of Life and the Life of Signs. Scranton: University of Scranton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeyer, Jesper. 2010b. Semiotic Freedom: An Emerging Force. In Information and the Nature of Reality: From Physics to Metaphysics. Edited by Paul Davies and Niels Henrik Gregersen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Hugon, Pascale. 2011. Dharmakīrti’s Discussion of Circularity. In Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. Edited by Mark Siderits, Tom Tillemans and Arindam Chakrabarti. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 109–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jantsch, Eric. 1992. The Self-Organizing Universe: Scientific and Human Implications of the Emerging Paradigm of Evolution. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katsura, Shōryū. 2011. Apoha Theory as an Approach to Understanding Human Cognition. In Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. Edited by Mark Siderits, Tom Tillemans and Arindam Chakrabarti. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 125–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kaw, R. K. 1967. The Doctrine of Recognition (Pratyabhijñā Philosophy): A Study of Its Origin and Development and Place in Indian and Western Systems of Philosophy. Vishveshvaranand Indological Series, no. 40; Hoshiarpur: Vishveshvaranand Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, David Peter. 1999. Rediscovering God with Transcendental Argument: A Contemporary Interpretation of Monistic Kashmiri Śaiva Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, David Peter. 2008a. The Teachings of the Odd-Eyed One: A Study and Translation of the Virūpākṣapañcāśikā with the Commentary of Vidyācakravartin. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, David Peter. 2008b. Abhinavagupta’s Philosophical Hermeneutics of Grammatical Persons. Journal of Hindu Studies 1: 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, David Peter. 2013b. The Plurality and Contingency of Knowledge, and its Rectification According to the Pratyabhijñā. In Abhinavā: Perspectives on Abhinavagupta, Studies in Memory of K.C. Pandey on His Centenary. Edited by Navjivan Rastogi and Meera Rastogi. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, pp. 226–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, David Peter. 2014. The Linguistics and Cosmology of Agency in Nondual Kashmiri Śaiva Thought. In Free Will, Agency and Selfhood in Indian Philosophy. Edited by Edwin F. Bryant and Matthew R. Dasti. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magliola, Robert. 1984. Derrida on the Mend. East Lafayette: Purdue University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, Patrick. 2014. The Neuroscience of Religious Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Charles. 1938. Foundations of the Theory of Signs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olivelle, Patrick. 2016. The Āśrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, Kanti Chandra. 1963. Abhinavagupta: An Historical and Philosophical Study. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, John R. 1980. An Introduction to Information Theory: Symbols, Signals and Noise, 2nd ed. New York: Dover. [Google Scholar]

- Pind, Ole Holten. 2011. Dignāga’s Apoha Theory: Its Presuppositions and Main Theoretical Implications. In Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. Edited by Mark Siderits, Tom Tillemans and Arindam Chakrabarti. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. 1989. The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Including the Letters. Edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Bollingen Series 57; Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prueitt, Catherine. 2016. Carving out Conventional Worlds: The Work of Apoha in Early Dharmakīrtian Buddhism and Pratyabhijñā Śaivism. Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 1985. Purity and Power among the Brahmans of Kashmir. In The Category of the Person: Anthropology, Philosophy, History. Edited by Michael Carrithers, Steven Collins and Steven Lukes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 190–216. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, Claude E., and Warren Weaver. 1998. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siderits, Mark. 2011. Śrughna by Dusk. In Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. Edited by Mark Siderits, Tom Tillemans and Arindam Chakrabarti. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Siderits, Mark, Tom Tillemans, and Arindam Chakrabarti, eds. 2011. Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stcherbatsky, Tom. 1962. Buddhist Logic. 2 vols. New York: Dover, Reprint. [Google Scholar]

- Tillemans, Tom. 2011. How to Talk about Ineffable Things: Dignāga and Dharmakīrti on Apoha. In Apoha: Buddhist Nominalism and Human Cognition. Edited by Mark Siderits, Tom Tillemans and Arindam Chakrabarti. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Timalsina, Sthaneshwar. 2014. Semantics of Nothingness: Bhartṛhari’s Philosophy of Negation. In Nothingness in Asian Philosophy. Edited by JeeLoo Liu and Douglas L. Berger. London: Routledge, pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Utpaladeva. 1921. The Siddhitrayī and the Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikāvṛtti. Edited by Madhusudan Kaul Shastri. Kashmir Series of Texts and Studies, no. 34; Srinagar: Kashmir Pratap Steam Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whicher, Ian. 1998. The Integrity of Yoga Darśana: A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, David Gordon. 2003. Kiss of the Yoginī: “Tantric Sex" in its South Asian Contexts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimizu, Kiyotaka. 2018. How can the Word ‘Cow’ Exclude Non-cows. Journal of Indian Philosophy 45: 973–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaehner, Robert Charles, ed. 1975. The Bhagavad-Gītā, with a Commentary Based on the Original Sources. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The disclosure of emanatory and cosmocratic Śakti is also described as the awakening of Pure Wisdom (śuddha vidyā), in which all objective things or “thises” (idam) are absorbed into the omnipotent I (aham) as “I am this” (aham idam) (IPK and IPV 3.1.3–7 in Abhinavagupta 1986, vol. 2, pp. 221–32; see Lawrence 1999, pp. 57–65). |

| 2 | Elaborating on similar assertions by Utpaladeva, Abhinavagupta explains, “Being [sattā] is the agency of the act of becoming [bhavanakartṛtā], that is, agential autonomy [svātantrya] regarding all actions.” sattā ca bhavanakartṛtā sarvakriyāsu svātantryam. IPV 1.5.14, (Abhinavagupta 1986, vol. 1, pp. 258–59). |

| 3 | See also Timalsina 2014 on Bhartṛhari. There has been much controversy in contemporary scholarship about the historical changes of the Buddhist apoha theory, including whether Dignāga’s approach towards a more “top down” understanding of vikalpa in inferential classifications was subverted by Dharmakīrti into a more “bottom up” orientation towards how constructions exclude irrelevant particulars (Siderits et al. 2011). Tom Tillemans, Georges Dreyfus, and John D. Dunne have suggested that Dharmakīrti shifted towards a natural theory of reference in focusing on the causation of apoha in the Buddhist account of the dependent origination of human behaviors (Tillemans 2011; Dreyfus 2011; Dunne 2011). Broadly, exclusion is the basis of what Dharmakīrti conceived as a “coordination” (sārūpya) between concepts and the particulars, of ironically explaining a “similarity between things absolutely dissimilar.” Stcherbatsky (1962), Buddhist Logic, vol. 1, p. 205. |

| 4 | See Lawrence 2013b on the Pratyabhijñā version of individual and cultural factors on which cognition is contingent. |

| 5 | Prueitt also points to the anti-Yogācāra significance of the Pratyabhijñā appropriation and subsumption of the material-causation scheme of Sāṃkhya categories, and stress on the ultimate continuity (as expressions of Śakti) between puruṣa and pakṛti. That appropriation, subsumption, and assertion of a continuity is basic to the tantric traditions, found in numerous nondual Śaiva, Sahajiya and Śākta texts (in fact it was the subject of one of my University of Chicago Ph.D. exam questions written by Wendy Doniger in the mid 1980’s). It is a constant theme of the diffuse 6–14th Devī Bhagavatam. I also think that the issues between Buddhists and Śaivas are of greater gravity than to be analogized respectively to defeatism and mastery of a video game (Prueitt 2016). Essentially a tantric understanding of the categories is what is advocated by Ian Whicher (1998). Al Collins is also pursuing this understanding in his studies (personal communication). |

| 6 | I think the mutual (and often conventional) bifurcations of the Peircean triad of sign, object and interpretant still persist with an iconic symbol. In mantric practice, even those dichotomies are supposed to be collapsed. |

| 7 | A common argument is that the Buddhist theory is also circular. We still need to know what a cow is in order to conceive of non-cows and not non-cow. (Hugon 2011). Yoshimizu (2018) claims to have shown that such a criticism is unfounded. |

| 8 | Abhinava is trying to show that the non-pot is a viable alternative. |

| 9 | This is the Sanskrit: ghaṭe hi dṛṣte ghaṭasthāna evāghaṭo’pi yogyadeśābhimatasthānākramaṇaśīlo vijñānajnakaḥ svakāraṇopnītaḥ sabhāvyate paṭādisvabhāvaḥ, ato ghaṭāghaṭayordvayoravabhāsasya sambhāvanāt samāropaḥ sāvakāśo bhavati, aghaṭasya satyārope niṣedhanalakṣaṇopohanvyāpāraḥ iti tadanuprāṇitā vikalparūpatā ghaṭa ityetasya niścayasya. IPV 1.6.2, vol. 1, p. 306. This conception is related to ideas seen from the beginning about determinate ascertainment using exclusion to overcome doubt:

Maintaining the Hindu and Buddhist concern with practice, Abhinava also observes that semantic reference and exclusion are basic to the behaviors of accepting and rejecting things. Thus he states:

It is because it has this rudimentary epistemological function that Abhinava asserts that the Semantic Exclusion Śakti aids both the Memory and Cognition Śaktis. evaṃ smṛtiśaktijñānaśaktiśca nirūpitā. atha tadubhayānugrāhiṇī apohanaśaktirvtatya … nirṇīyate. IPV 1.6 introduction, vol. 1, pp. 299–300. |

| 10 | These are Utpaladeva’s original verses:

The Gītā of course was not addressing the Buddhist apoha, but the meaning is, as we shall see, not necessarily irrelevant. See also IPK and IPV 1.6 intro.-6, vol. 1, pp. 299–327. |

| 11 | This is his translation:

|

| 12 | See the discussion of Platonism below. |

| 13 | tadavikalpadaśāyāṃ citsvabhāvo’sau ghaṭaḥ cidvadeva viśvaśarīraḥ pūrṇaḥ, na ca tena kaścidvyavahāraḥ, tat māyāvyāpāramullāsayan pūrṇamapi khaṇḍayati bhāvaṃ, tenāghaṭasyātmanaḥ paṭādeścāpohanaṃ kriyate niṣedhanarūpam, tadeva vyapohanamāśritya tasya ghaṭasya niścayanamucyate ‘ghaṭa eva’ iti, evārthasya sambhāvyamānāparavastuniṣedharūpatvāt, eṣa eva paritaśchedāntakṣaṇakalpāt paricchedaḥ. IPV 1.6.3, vol. 1, pp. 309–10. The idea of fragmentations is also well-articulated in the following passage:

For another description of the creation of the limited subject distinguished from objects, which invokes both the terms Māyā and Exclusion, see IPK and IPV 1.6.4–5, vol. 1, pp. 312–23. |

| 14 | nanu ghaṭe pariniṣṭharūpe dṛṣṭe taddarśanamupajīvatā vikalpena kathamaghaṭasya niṣedhanaṃ kriyate, na hyaghaṭasya kenacinnāmāpi gṛhītam, aghaṭvāsnāpi ghaṭe dṛṣṭe kathaṃkāram prabudhyatām? satyam, evaṃ śākyaḥ paryanuyojyo na tu vayaṃ (IPV 1.6.3, vol. 1, p. 308) According to Bhāskarakaṇṭha, there is only supposed to be the awakening of the mental impression of that which is similar to an object of cognition. Bhāskarakaṇṭha’s commentary Bhāskarī on the IPV (BIPV) 1.6.3, vol. 1, p. 308. |

| 15 | This is the Sanskrit:

Abhinava supports the idea of the subject’s comprehension of both the that and the not-that with the analogy of a city reflected in a mirror. cinmātraśarīro’pi tatsāmānādhikaraṇyavṛttirapi darpaṇanagaranyāyenāsti—ityapi uktam (IPV 1.6.3, vol. 1, p. 309). Cf. the explanation of pratibhā by Abhinavagupta at IPV 1.7.1, vol. 1, pp. 352–55. Here, he identifies it with the Great Lord/subject having the nature of self-recognition, and asserts its effectuation of both the conjunction and disjunction of things. |

| 16 | This is the Sanskrit:

|

| 17 | Bādha is explained similarly. Cf. IPK and IPV 1.7.6–13, vol. 1, pp. 364–89. |

| 18 | iha pramātā nāma pramāṇādatiriktaḥ pramāsu svatantraḥ saṃyojanaviyojanādyādhānavaśāt kartā darśitaḥ (IPV 1.6.3, vol. 1, p. 309). Abhinavagupta asserts that even the Buddhists contradict their own theses by inadvertently acknowledging ekapratyavamarśa by the pramātṛ. In the discussion of the triad of epistemic Śaktis taken from the Bhagavad Gītā, Abhinava explains that by them the ordinary person is the agent or direct perception (anubhavitṛ), agent of memory (smartṛ), and agent of conceptual constructions (vikalpayitṛ). He quotes Ajaḍapramātṛsiddhi (yadyayarthasthitiḥ prāṇapuryaṣṭakaniyantrite, jive niruddhā tatrāpi paramātmani sā sthitā; see Utpaladeva 1921, vol. 1, pp. 8, 20) that things which seem to be established in the individual are actually established in the Supreme Self, and again further elaborates that all these epistemic Śaktis come from the Lord’s perfect agential autonomy (svātantrya) (IPV 1.3.7, vol. 1, pp. 143–44). |

| 19 | Though the Lord’s self-recognition synthesizes the exclusion in gross conceptual construction, the Śaivas stress that this recognition is not made through it. They deny the possibility of a superimposed alternative to be negated on the basis of the familiar idealistic premise that “there cannot be the manifestation of another, like awareness, which is different [from awareness]”.

Also see IPV 1.6.1–2, vol. 1, pp. 301–8. In this regard, a distinction is made between two levels of I, the nonconceptually constructed recognitive apprehension, Supreme Speech and so on, and the conceptually constructed self that is distinguished from the non-self. IPK and IPV 1.6.4–6. I note that the creative freedom evident in acts of fantasy (e.g., of an elephant with a hundred tusks and two trunks) is also taken by the Śaivas as demonstrating the principle that all dichotomizing conceptual construction is generated by the Lord's Exclusion Śakti. See IPK and IPV 1.6.10–11, vol. 1, pp. 337–43. Cf. the precursor to the Pratyabhijñā in the holism and intentionality toward Being in the semantics of negation in Bhartṛhari, in Timalsina 2014. Thomist Emerich Coreth asserts:

|

| 20 | Abhinava explains:

Cf. taduktiśca prakṛtāyāmīśvararūpasvātmaprayabhijñāyāmupayujyate iti ślokena. IPV 1.6 introduction, vol. 1, p. 301. |

| 21 | I am also reminded of Heidegger’s account of how unity leads to difference in his difficult Identity and Difference (Heidegger 1969). |

| 22 | This gives a taste of the main part of the discussion:

|

| 23 | Deacon believes that concepts of information in Shannon, Boltzmann, and Darwin roughly parallel the classic distinctions, respectively, between syntax, semantics, and pragmatics (Deacon 2012, p. 414). |

| 24 | A couple of less telling passages:

|

| 25 | (Deacon 2012, vol. 182, pp. 191–92), homologizes difference with constraint, and quotes with approval Ashby 1962, p. 257:

|

| 26 | Incidentally, both Amita Chatterjee in her interpretation of Dharmakīrti and Deacon in his difference-based biosemiotics (Chatterjee 2011) find support in James Gibson’s notion of sensory-motor “affordances” (2015). |

| 27 | See the discussion of the binary derivation of early Chomskian phrase structures in “Language and Meaning” (Pierce 1980, pp. 107–24). |

| 28 | Though not always so candidly acknowledged, the application of Peircean semiotics to biology is in effect a kind of neo-vitalism. With respect to the current discussion of semantic exclusion, we may be reminded of the reflections on negation of the earlier vitalist, Henri Bergson. Discussing a different sort of idea of “nothingness”, “void”, or “nought” as the negation of presence and intended order in our teleological pursuits, Bergson makes the relevant observation:

Kenneth Burke is influenced by Bergson in his famous “Definition of Man”, where negation is basic to the intentionalities of symbol use and moral striving:

|

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lawrence, D.P. Pratyabhijñā Apoha Theory, Shannon–Weaver Information, Saussurean Structure, and Peircean Interpretant Agency. Religions 2018, 9, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9060191

Lawrence DP. Pratyabhijñā Apoha Theory, Shannon–Weaver Information, Saussurean Structure, and Peircean Interpretant Agency. Religions. 2018; 9(6):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9060191

Chicago/Turabian StyleLawrence, David Peter. 2018. "Pratyabhijñā Apoha Theory, Shannon–Weaver Information, Saussurean Structure, and Peircean Interpretant Agency" Religions 9, no. 6: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9060191

APA StyleLawrence, D. P. (2018). Pratyabhijñā Apoha Theory, Shannon–Weaver Information, Saussurean Structure, and Peircean Interpretant Agency. Religions, 9(6), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9060191