1. Introduction

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) have high potential to improve the properties of polymers. Due to their unique structure and high aspect ratio (length to diameter ratio, L/D), they possess an outstanding combination of exceptional mechanical, electrical and thermal properties in addition to flexibility and low density. Nevertheless, CNTs give rise to aggregation due to their high aspect ratio, flexibility, strong inter-tube Van Der Waals (VDW) attraction. The key factors for properties improvement of polymer/CNT nanocomposites are good dispersion and low agglomeration [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Consequently, two approaches have been proposed to disperse CNT in polymer matrix: application of stresses to break mechanically the agglomerates and obtain adequate dispersion and surface treatments of CNT based on chemical and physical methods [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. According to Coleman

et al. [

3] well dispersed CNT is of utmost importance to maximize the interfacial area, to achieve efficient load transfer and minimize the presence of stress concentration centers. The frictional forces in polymer/CNT interfaces are expected to be large and, even if debonding has occurred, there will be significant load transfer from the polymer to the CNT, contrary to traditional fiber reinforced composite, where complete debonding implies failure of the composite [

11,

12,

13,

14]. According to Huang

et al. [

14] good dispersion can be seen at low concentrations of CNT and they re-aggregate after long period of time. At concentrations above the threshold (2-3 wt %) an elastic gel of entangled CNT has been observed. Furthermore, high concentration of CNT in epoxy increases resin viscosity and makes the dispersion of CNT extremely difficult [

15]. Compatible surface treatment of CNT with the epoxy matrix has been found to give good stress transfer at the interface [

4]. An effective dispersion of CNT requires overcome inter-tube attraction, separating CNT from aggregates and stabilizing them within the polymer matrix. In order to optimize the dispersion of CNTs in a polymer matrix chemical surface treatments can be used together with mechanical dispersion methods (ultrasonication, calendering, ball milling and shear mixing) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Direct covalent treatment is associated with a change of hybridization from sp

2 to sp

3 and a simultaneous loss of ð-conjugation system in CNT. This is achieved by processes such as: fluorination, hydrogenation, cyclo-addition, oxidation and further derivative reactions. Defect sites on CNT surface like: open ends, holes in the sidewalls, irregularities in CNT scaffold, are utilized in order to tie up different functional groups. Oxidation can be obtained by wet chemical methods with concentrated acids or by milder approaches using the photo-oxidation, oxygen plasma, or gas phase treatment. [

10,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Covalent treatments greatly enhance the solubility of CNT and can provide multiple and strong bonding sites to the polymer matrix. It is believed that the improvements in nanocomposite properties are addressed in connection with improved dispersion and efficient load transfer via epoxy/CNT interface. However, this route can strongly influence the intrinsic characteristics of CNT and result in fragmentation and degradation of CNT structure, which further reflects in the overall performance of polymer/CNT nanocomposites [

7,

15].

Table 1 summarizes the main literature based experimental results and emphasizes the effect of covalent treatment for MWCNT on the thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites. It can be noticed that small amounts of covalent treated MWCNT (in most cases less than 1 wt %) have a positive effect on thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites. The results show an average increase of 40%-50% in modulus and strength and an average increase of 20% of Tg, compared to neat epoxy. Covalent treated MWCNT also improved the toughness of nanocomposites. In addition, amino-functionalization seems to be a usual surface treatment of CNT due to its high reactivity with epoxy resin [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Non-covalent treatments are an efficient alternative route to functionalized CNT and yet preserving the intrinsic characteristics of CNT and ð-conjugation system. In addition, this route leads to higher efficiency of the functionalization, compare to covalent treatments where VDW active sites on CNT surface are limited (mostly at the defects and end caps). There are three main methods for non-covalent CNT treatments: (a) polymer wrapping; (b) surfactant adsorption and (c) endohedral method. Polymer wrapping process is achieved through the interactions and ð-ð stacking between CNT and polymer chains containing aromatic rings. The surfactants studied are classified according to the charge of their head groups: nonionic, anionic and cationic. In general, ionic surfactants have some advantages in water-soluble polymers, while nonionic surfactants are proposed in case of water-insoluble polymers. There are three possible surfactant-CNT interaction mechanisms: (a) electrostatic attraction or repulsion; (b) hydrogen bonding between the -O- of polyethoxylate and -OH and/or -COOH groups of CNT and; (c) hydrophobic and π-π interactions. According to Vaisman

et al. [

8] it is important to achieve mechanical dispersion of CNT prior to surfactant adsorption in order to obtain an efficient de-agglomeration of CNT. In the “endohedral” method guest atoms or molecules are inserted in the inner cavity of CNT through defect sites localized at the ends or on the sidewalls [

10,

39,

40]. Surfactants composed of hydrophilic polyethoxyl group (including polyethoxyl chain and hydroxyl groups) and hydrophobic group (4-(1,1,1,3-tetramethylbutyl)-phenyl group) bridge between CNT and polymers [

39,

40]. According to Bai

et al. [

40] adsorption of Triton X-series (

i.e., Triton X-305, Triton X-165, Triton X-114, Triton X-100) surfactants facilitates the suspension of MWCNT in water mainly by hydrophobic and π-π interactions mechanisms. Furthermore, Triton X-series with shorter hydrophilic chains showed higher suspendability of MWCNT, which could be affected by the surfactant adsorption and, also possibly through the formation of larger micelles both in surfactant solution and on MWCNT surface at the surfactant concentration above the CMC. Rastogi

et al. [

41] investigated the dispersion of MWCNT in aqueous medium using four different surfactants. It was concluded that Triton X-100 (Polyoxyethylene octyl phenyl ether) has the highest dispersing power by virtue of its benzene ring. Molecules having a benzene ring structure adsorb more strongly to the graphitic surface due to π-π stacking type interaction. In addition, MWCNT-to surfactant ratio has shown to affect the MWCNT dispersion significantly. The poor dispersion at high surfactant loading was concluded to be caused by a possible mechanism of flocculation. Flocculation of CNT occurs when portions of surfactant molecules interact with others surfactant molecules on neighboring CNT, thus bridging between CNT and avoid dispersion. Coating of CNT surface is an additional method based on non-covalent treatments. CNT was coated with a precursor of titania by sol-gel or hydrothermal methods [

42,

43,

44,

45]. In order to improve the affinity of titania coated CNT to a polymer it can be modified with a coupling agent such as silane.

Sol-gel coatings can be obtained by a simple process based on hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions carried usually at room temperature [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47].

Table 2 summarizes the main literature based experimental results emphasizing the effect of different non-covalent treated MWCNT on thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites. It can be concluded that small amounts of non-covalent treated MWCNT (1 wt %) have a positive effect on thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites. An average increase of 50%-60% in modulus and strength and 20% in Tg could be noticed. Non-covalent treated MWCNT also improved the toughness of nanocomposites [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56].

Table 1.

Effect of covalent treatment of MWCNT on the thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites.

Table 1.

Effect of covalent treatment of MWCNT on the thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites.

| Covalent treatment | Mechanical dispersion | Solvent dispersion | Content (wt %) | Maximum increase in thermo-mechanical properties compared to neat epoxy (%) | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|

| ModulusS,T,F | StrengthT,F | Tg | Toughness |

|---|

| Amino groups | Stirred, sonicated | | 0.01-1 | 18.95F | 120.41F | 10.53 | | Aromatic and less aliphatic amino group structure is better for mechanical reinforcement. | 15,28 |

| Sonicated | | 0.05-0.75 | | | 29.69 | | Suspension of MWCNT was performed within the hardener. | 29 |

| Stirred, sonicated | Acetone | 0.1-2 | | 51T | 22.38 | 93 (kJ/m2) | Amino groups can act as a curing agent and lead to a more highly cross-linked structure. | 30 |

| Stirred | | | 53S | 26.32F | 5.34 | | Amine functionalization improved curing kinetics. MWCNT content was 3 phr of epoxy resin. | 31 |

| TETA Tri ethylene tetra amine | Stirred, sonicated | Ethyl alcohol | 0.2-1 | 22F | 29F | | 84 (kJ/m2) | | 32 |

| Stirred, sonicated | | 0.05-0.5 | | | 18.64 | 97 (kJ/m2) | Epoxy contain 0.05 wt % TETA-MWCNT kept near 50% light transmittance of the neat epoxy. | 33 |

| Polyetheramine (JeffamineT-403) | Stirred, sonicated | Chloroform | 1 | 27.51T | 104.17T | | | Mechanical properties of nanocomposites based rubbery system (Tg = 25 °C) was higher compared to glassy system (Tg = 80 °C). Suspention of MWCNT was performed within the hardener. | 16 |

| Oxidation | Sonicated | Acetone | 1 | 75S (HNO3 treatment) | | | | The increase of surface oxygen per type of treatment is: HCl< NH4OH/H2O2 < piranha < refluxed HNO3. Higher degree of oxidation leads to higher degradation of the CNT shell. | 27 |

| Plasma oxidation | Sonicated | | 1 | 2. 33T | 123T | | | Nanocomposites containing plasma treated MWCNT showed the best mechanical and rheological behavior, compared to those containing acid and amine treated MWCNT. | 34 |

| Plasma maleic anhydride | Shear mixed, sonicated | | 0.1-1 | 100T | 50T | 27 | | Suspension of MWCNT was performed within the hardener. | 35 |

| Silane | Sonicated | Ethanol | 0.05-0.5 | 24.14F | 14.40F | 8.84 | 10.17(MPa m2) | | 36 |

| Epoxy | Stirred, sonicated | Acetone | 0.1-1 | 90T | 45T | 16.67 | | | 37 |

| PEI | Stirred, sonicated | Acetone | 1 | | | | | PEI was covalently and non-covalently attached to MWCNT. Covalently treated MWCNT exhibited higher storage modulus compare to non-covalently treated and untreated MWCNT. | 38 |

Table 2.

Effect of non-covalent treated MWCNT on the thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites.

Table 2.

Effect of non-covalent treated MWCNT on the thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites.

| Non-covalent treatment | Mechanical dispersion | Solvent dispersion | Content (wt %) | Maximum increase in thermo-mechanical properties compared to neat epoxy (%) | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|

| ModulusS,T,F | StrengthT,F | Tg | Toughness |

|---|

| Sodium salt of 2-aminoethanol | Sonicated | | 0.1 | 26S | | | | Improvement in electrical conductivity with a percolation threshold of 0.05 wt % | 48 |

| Triton X-100 | Sonicated | Acetone | 0.025-0.25 | 24.14F | 17.92F | 27.59 | 51.51 (kJ/m2) | Triton X-100 (10 CMC) treatment showed the best performance. | 39 |

| Silane modified Titania coating | | Acetone | 0.25-1 | 85.03F 58.57T | 93.04F 115.90T | | | | 45 |

| Polyaniline coating | Sonicated | Toluene | 0.5-10 | 52T 150S | 61T | | | There is an optimal value of polyaniline concentration above which mechanical properties of nanocomposites decreased. | 49 |

| BCP (Disperbyk-2150) | Stirred, sonicated | Ethanol | 0.25 | 50T | 50T | | | The BCP act as dispersing agent: the lyophobic (solvent repelling) blocks adsorb onto the surface of CNT, while the lyophilic (solvent attracting) blocks are swollen by the solution. | 50,51 |

| 0.5-1 | | | 23.21 | |

| Titania coating | Homogenized | | 0.05-0.3 | 31.8S | | | | Previous study. Tan delta curves below the Tg of nanocomposites showed increase in toughness without dependency in MWCNT treatment. | |

| Sonicated | | 0.05-0.3 | 27S | | 10 | | Current study. MWCNT treated with Triton X-100 didn’t show thermo-mechanical improvement. |

Table 3.

Epoxy systems [

57,

58,

59].

In the current study, Multi Wall Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNT) were surface treated and incorporated into epoxy matrix. One of the MWCNT treatments was based on a titania (TiO2) coating obtained by sol-gel process. The surfactant Polyoxyethylene octyl phenyl ether (Triton X-100) was also used as a surface treatment. The study focused on the influence of MWCNT content and surface treatment on thermo-mechanical properties of the nanocomposites. The objective of this work was to characterize the properties of epoxy CNT nanocomposites based to be used as composite's matrix for filament winding technology. The main factor in selecting a resin for filament winding is adequate viscosity. Low viscosity is desirable to help wet the fibers, spread the fibers and lower the friction over the guides during the winding process.

3. Results and Discussion

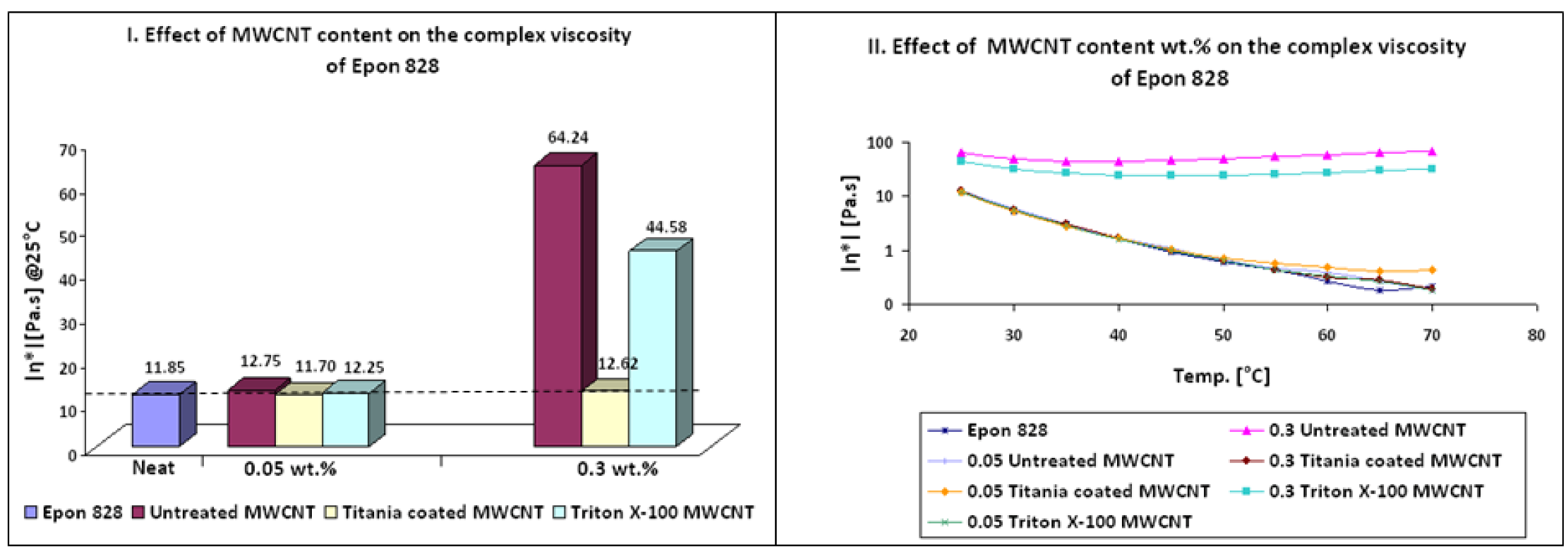

Results of complex viscosity |η*| of Epon 828/MWCNT suspensions before curing were obtained by Dynamic Parallel Plate Rheometry and can be seen in

Table 5 and

Figure 1. It can be noticed that addition of 0.05 wt % untreated or treated MWCNT did not change significantly the complex viscosity of Epon 828 at the temperature range tested. At higher contents of MWCNT only titania coated MWCNT suspensions maintained the low viscosity of neat epoxy matrix. According to Abdalla

et al. [

17] higher viscosity indicates of either a better dispersed system or stronger interfacial interactions. Conversely, Song

et al. [

64], claimed that poorly dispersed CNT in epoxy resin have a more solid-like behavior and leads to higher complex viscosity. In the current study, at 0.3 wt % MWCNT loading, untreated MWCNTs exhibited the highest complex viscosity and the lowest thermo-mechanical properties after curing. These findings can only suggest that untreated MWCNTs lead to a relatively poor dispersion, while the titania coated MWCNTs lead to better dispersion. In addition, it can be assumed that titania coating reduced the VDW interaction between MWCNTs themselves by neutralizing the polar groups known to be present at MWCNT surface. In order to maintain the low viscosity the content of untreated and Triton X-100 treated MWCNTs should be lower than 0.3 wt %.

Table 5.

Complex viscosity |η*| of Epon 828/MWCNT suspensions before curing.

Table 5.

Complex viscosity |η*| of Epon 828/MWCNT suspensions before curing.

| Sample | Additive (wt %) | Complex viscosity (Pa.s) @25 °C | Complex viscosity variation (%) |

|---|

| Untreated MWCNT | 0.05 | 12.75 | 8 |

| 0.30 | 64.24 | 442 |

| Titania coated MWCNT | 0.05 | 11.70 | −1 |

| 0.30 | 12.62 | 6 |

| Triton X-100 MWCNT | 0.05 | 12.25 | 3 |

| 0.30 | 44.58 | 276 |

Figure 1.

Effect of MWCNT content on the complex viscosity of Epon 828 before curing.

Figure 1.

Effect of MWCNT content on the complex viscosity of Epon 828 before curing.

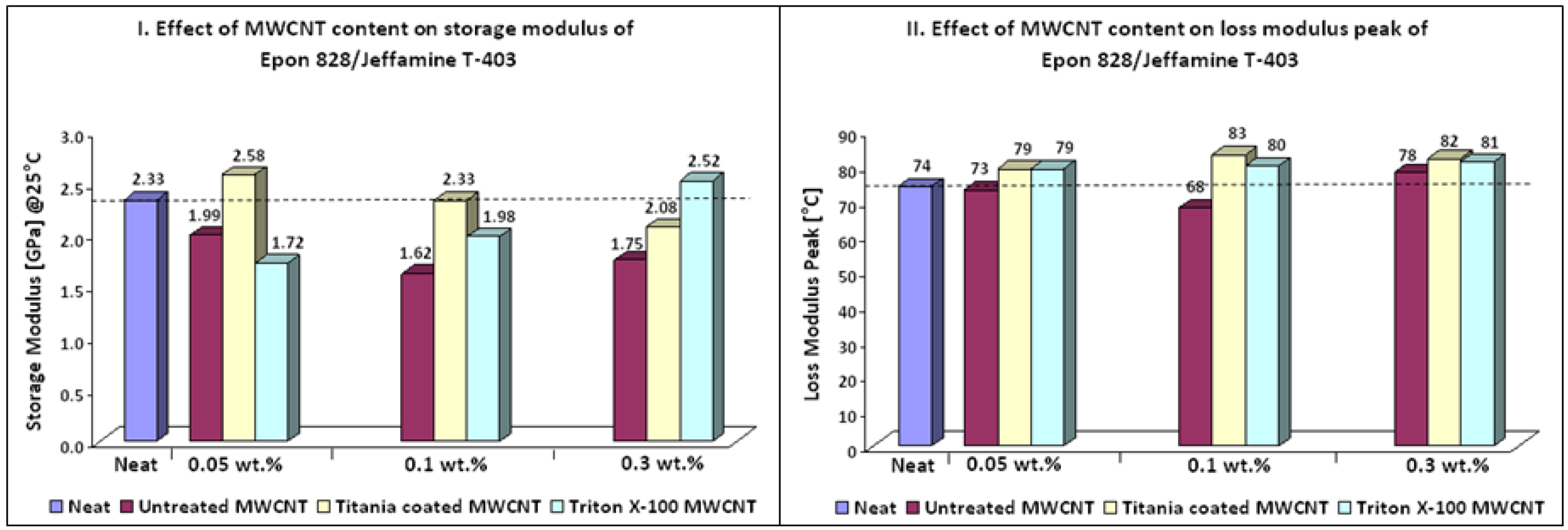

Thermo-mechanical properties of Epon 828/Jeffamine T-403 nanocomposites are depicted in

Table 6 and

Figure 2. It can be seen that addition of treated MWCNTs caused a higher crosslink density compared to neat resin, as could be noticed by the increase of approximately 10% in the Tg of the nanocomposites. Furthermore, treated MWCNT induced an increase in thermal stability of nanocomposites in the rubbery state of storage modulus (

Figure 3 b,e). According to Ma

et al. [

36] this behavior can be explained in terms of interfacial bonding. The improved interfacial bonding reduces the mobility of the matrix around the MWCNT, increasing thermal stability at elevated temperatures. Simultaneous increase of approximately10% in storage modulus and Tg can be seen for 0.05 wt % titania coated MWCNT and 0.3 wt % Triton X-100 MWCNT. Nanocomposites containing titania coated MWCNT showed the best thermo-mechanical properties. This finding can be due to the hydrophilic and polar nature of titania. Another explanation can be the possible chemical reaction between OH groups known present on CNTs surface and titanium precursor molecules [

42]. It should be mentioned that the addition of treated MWCNT did not lead to toughening effects.

Table 6.

Epoxy system 1: Thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites.

Table 6.

Epoxy system 1: Thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites.

| Sample | Additive (wt %) | Storage modulus (GPa) @25 °C | Storage modulus variation (%) | Loss modulus peak (°C) | Loss modulus peak variation (%) |

|---|

| Epon 828/Jeffamine T-403 | 0 | 2.33 | | 74 | |

| Untreated MWCNT | 0.05 | 1.99 | −15 | 73 | −1 |

| 0.10 | 1.62 | −30 | 68 | −8 |

| 0.30 | 1.75 | −25 | 78 | 5 |

| Titania Coated MWCNT | 0.05 | 2.58 | 11 | 79 | 7 |

| 0.10 | 2.33 | 0 | 83 | 12 |

| 0.30 | 2.08 | −11 | 82 | 11 |

| Triton X-100 MWCNT | 0.05 | 1.72 | −26 | 79 | 7 |

| 0.10 | 1.98 | −15 | 80 | 8 |

| 0.30 | 2.52 | 8 | 81 | 9 |

Figure 2.

Effect of MWCNT content on thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites (Epoxy system 1).

Figure 2.

Effect of MWCNT content on thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites (Epoxy system 1).

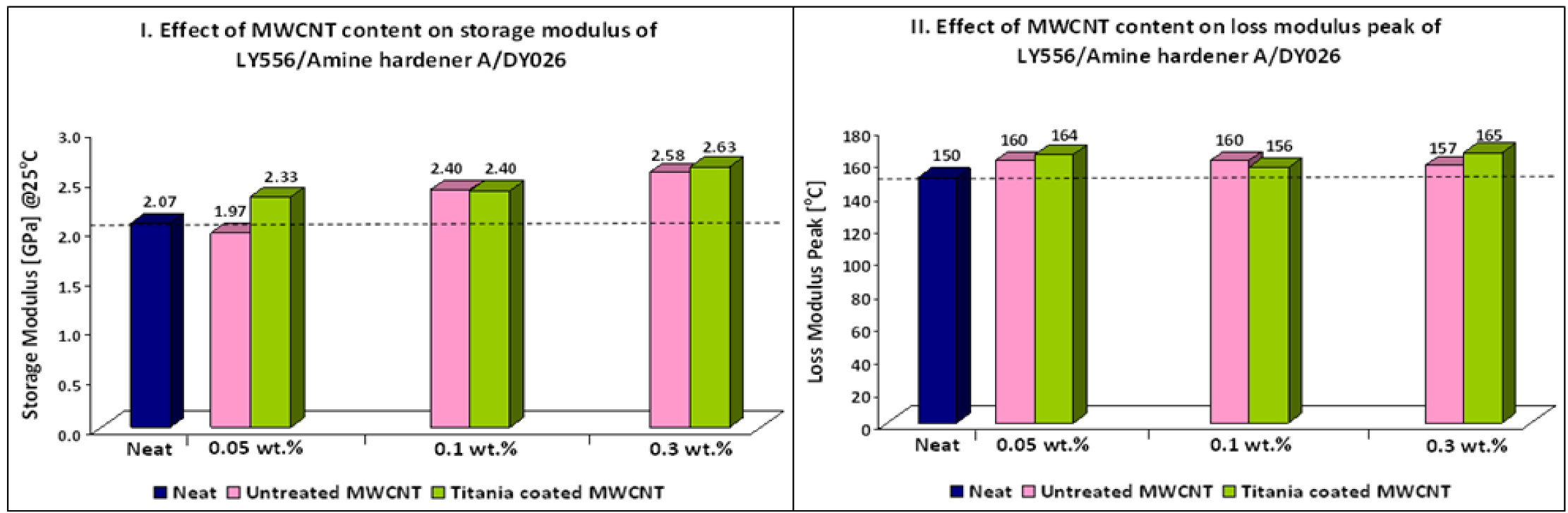

Table 7 and

Figure 3 show the thermo-mechanical properties of LY556/Amine hardener A/DY026 nanocomposites. An increase in the Tg of the samples containing titania coated and untreated MWCNTs was noticed, most probably as a result of a higher crosslink density. Moreover, an increase in storage modulus has been also observed through the whole temperature range investigated. Maximum increase of 10% in Tg and 30% in storage modulus was achieved for nanocomposites containing 0.3 wt % titania coated MWCNTs. The unexpected improvement in thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites containing untreated MWCNTs can be explained by the relatively low viscosity of LY556 resin. This characteristic imparts low shear forces during sonication resulting in less damage to the MWCNT structure. In addition, a relatively low viscosity of the matrix before curing favors the formation of uniform nanocomposites [

16]. These explanations can also relate to the better results obtained for nanocomposites containing titania coated MWCNTs of epoxy system 2 compared to epoxy system 1. It should be mentioned that toughening effects have not been observed.

Table 7.

Epoxy system 2: Thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites.

Table 7.

Epoxy system 2: Thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites.

| Sample | Additive (wt %) | Storage modulus (GPa) @25 °C | Storage modulus variation (%) | Loss modulus peak (°C) | Loss modulus peak variation (%) |

|---|

| LY556/Amine hardener A/DY026 | 0 | 2.07 | | 150 | |

| Untreated MWCNT | 0.05 | 1.97 | -5 | 160 | 7 |

| 0.10 | 2.40 | 16 | 160 | 7 |

| 0.30 | 2.58 | 25 | 157 | 5 |

| Titania Coated MWCNT | 0.05 | 2.33 | 13 | 164 | 9 |

| 0.10 | 2.40 | 16 | 156 | 4 |

| 0.30 | 2.63 | 27 | 165 | 10 |

Figure 3.

Effect of MWCNT content on thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites (Epoxy system 2).

Figure 3.

Effect of MWCNT content on thermo-mechanical properties of nanocomposites (Epoxy system 2).

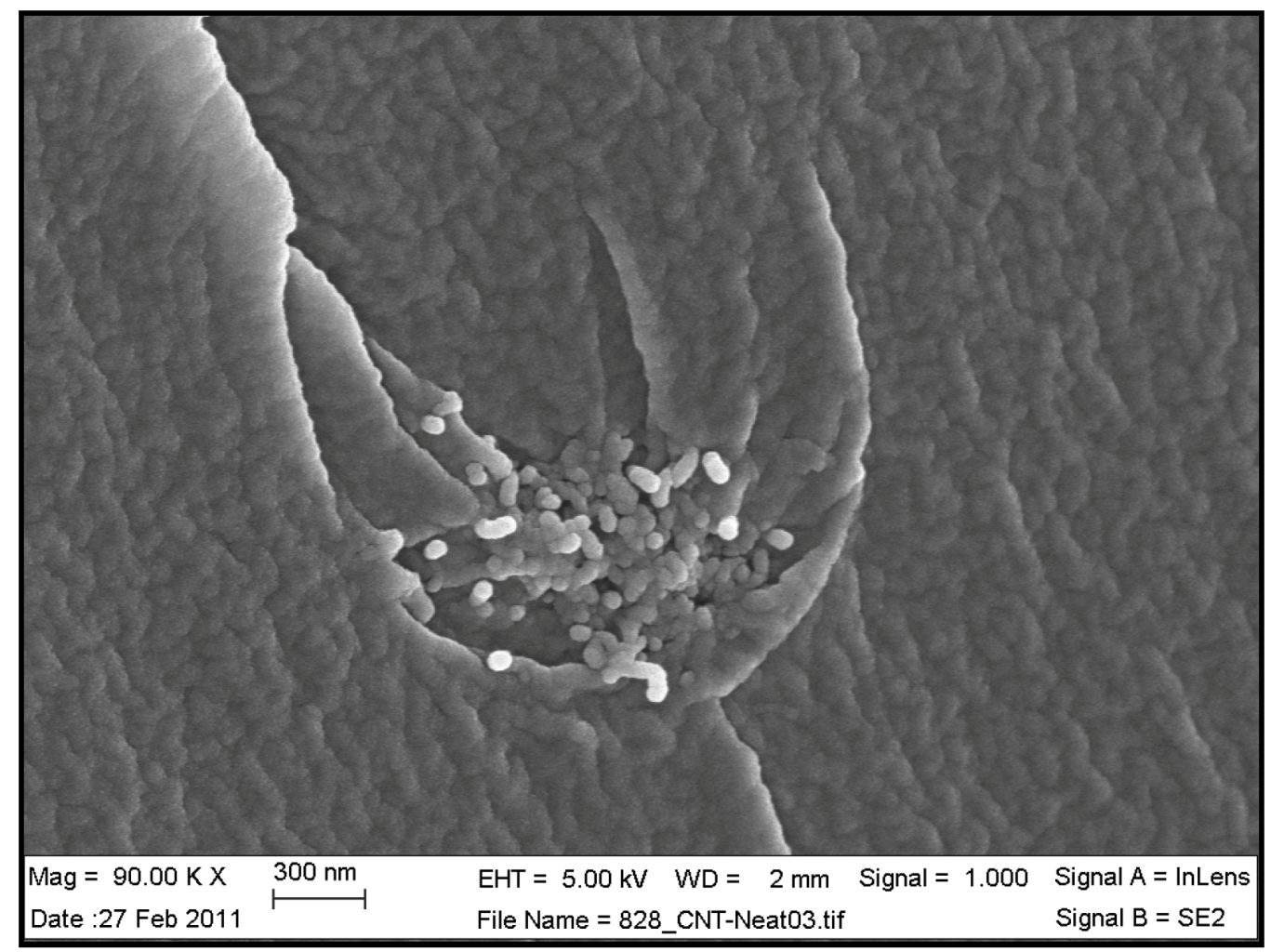

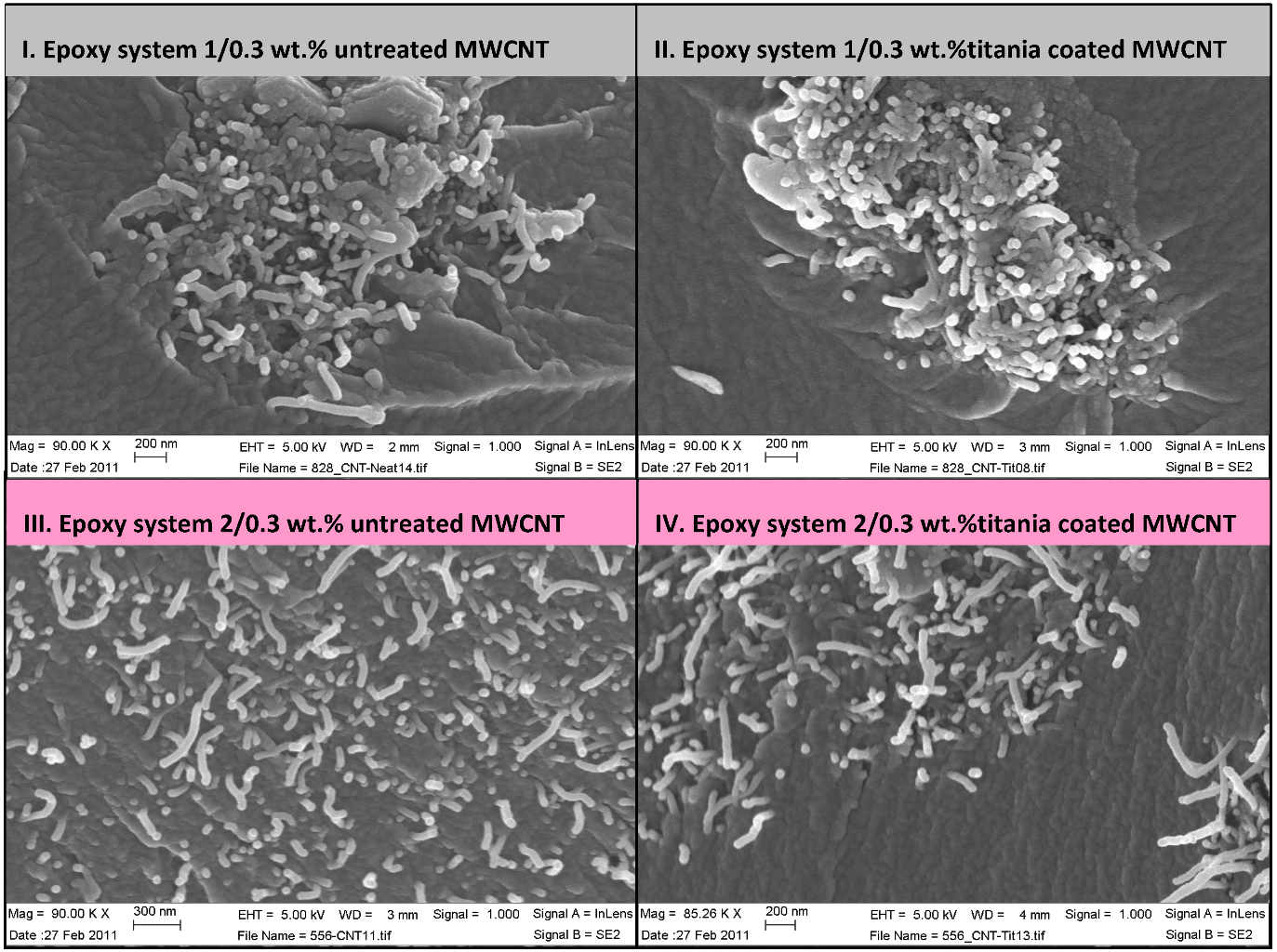

Figure 4 and

Table 8 show SEM and AFM images of fractured surface morphologies of nanocomposites contain 0.3 wt % MWCNT based on epoxy systems 1 and 2. Nanocomposites containing titania coated MWCNT and uncoated MWCNT have shown a fracture mechanism known as crack front bowing, that can clearly be seen from SEM image in

Figure 4. From AFM images (

Table 8) a crack pinning mechanisms was noticed for the titania coated MWCNT nanocomposites, a toughening mechanism that indicates the strong interaction between the carbon nanotubes and the epoxy matrix through the coating. The toughening effect could not be clearly seen in the thermo-mechanical results due to the poor dispersion in the matrix, in all cases.

Figure 4.

SEM image of epoxy system 1 with 0.3% untreated MWCNT showing a “crack front bowing” toughening mechanism.

Figure 4.

SEM image of epoxy system 1 with 0.3% untreated MWCNT showing a “crack front bowing” toughening mechanism.

Table 8.

AFM images of fractured surface morphologies of nanocomposites contain 0.3 wt% MWCNT.

Figure 5.

SEM images of titania coated and non-treated MWCNT nanocomposites.

Figure 5.

SEM images of titania coated and non-treated MWCNT nanocomposites.

Figure 5 depicts selected scanning electron microscopy images of surface fractured nanocomposites (cryogenic fracture) showing higher amounts of broken nanotubes in epoxy system 1 for both untreated and titania coated MWCNT samples. Broken nanotubes at the fracture surface indicate a strong interfacial strength. Longer nanotubes could be seen in SEM images of the epoxy system 2, indicating a pull-out mechanism, related to a weaker nanotube/matrix interface. According Gojny

et al. [

4] a fracture of the outer layer and a telescopic pull-out of the inner tube(s) can occur due to strong interfacial bonding. Accordingly it is possible that some images of pulled-out MWCNTs in

Figure 5 represent a nanotube inner layer pull-out, implying on a strong interfacial bonding.