Nanotoxicity: An Interplay of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Cell Death

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Toxicity of Nanoparticles

| Class/Type of Nanoparticles | Application in Nanomedicine | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric nanoparticles | ||

| Polysaccharide chitosan nanoparticles (CS-NPs) | Drug delivery [5] | Not reported |

| Poly-(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Cancer therapy and drug delivery [7] | Not reported |

| Inorganic nanoparticles | ||

| Silica nanoparticles | Drug delivery/Diagnostic imaging [9] | Platelet aggregation and physiological toxicity [52], reproductive toxicity [53] |

| Ceramic nanoparticles | Cancer drug delivery [8] | Oxidative stress/cytotoxic activity in the lungs, liver, heart, and brain [42] |

| Metallic nanoparticles | ||

| Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles | Magnetic resonance imaging contrast enhancement, immunoassays and cancer drug carrier systems [11,12] | Oxidative stress and disturbance in iron homeostasis [54] |

| Gold shell nanoparticles | Biomedical imaging and therapeutics [13] | Hepatic and splenic toxicity [55] |

| Titanium dioxide | Cancer therapeutics [14] | Toxicity to the central nervous system [46,47] |

| Silver nanoparticles | Antibacterial agents [15] | ER stress response not only in the lung, liver and kidneys [56] |

| Carbon nanoparticles (fullerenes and nanotubes) | Drug delivery [16,17] | Pulmonary toxicity and interstitial inflammation [40,41] |

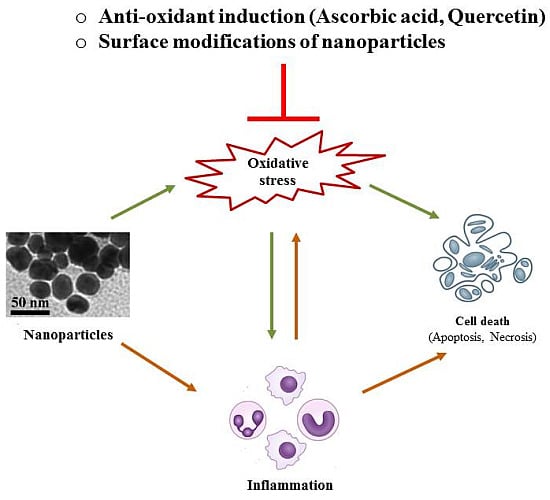

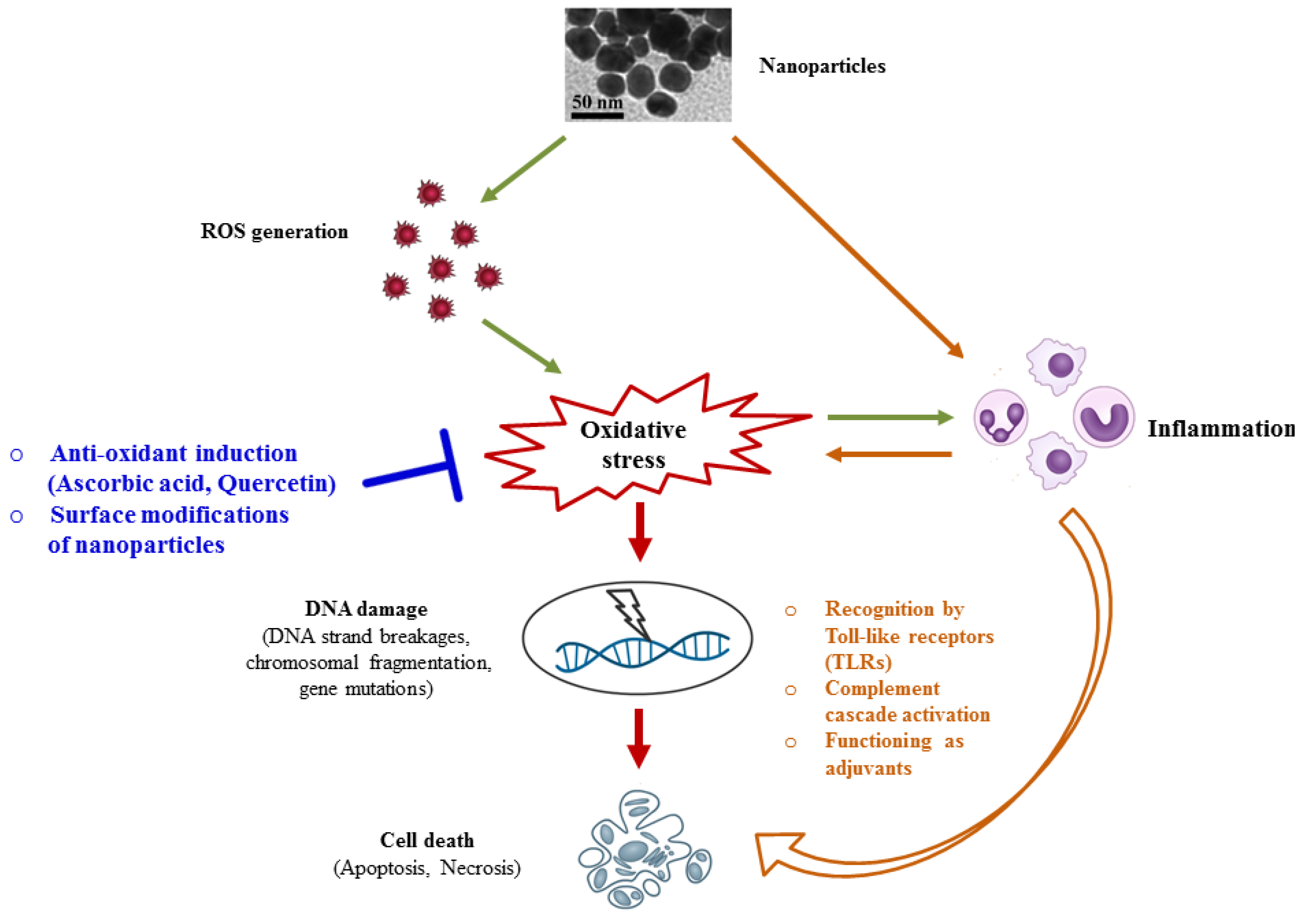

3. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Nanotoxicity

3.1. Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage

3.2. Inflammation-Mediated Nanotoxicity

4. Possible Strategies to Circumvent Nanotoxicity

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roco, M.C. National Nanotechnology Initiative—Past, Present, Future. In Handbook on Nanoscience, Engineering and Technology, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 3.1–3.26. [Google Scholar]

- Lanone, S.; Boczkowski, J. Biomedical applications and potential health risks of nanomaterials: Molecular mechanisms. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006, 6, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Science and Technology Council. National Nanotechnology Initiative Strategic Plan; Executive Office of the President of the United States: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Science Foundation. Nanomedicine: An. ESF-European Medical Research Councils (EMRC) forward Look Report; European Science Foundation: Strasbourg Cedex, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri, S.A.; Mallikarjuna, N.N.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Recent advances on chitosan-based micro- and nanoparticles in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2004, 100, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.J. Polymer nano-engineering for biomedical applications. Ann.Biomed. Eng. 2006, 34, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornaguera, C.; Dols-Perez, A.; Caldero, G.; Garcia-Celma, M.J.; Camarasa, J.; Solans, C. PLGA nanoparticles prepared by nano-emulsion templating using low-energy methods as efficient nanocarriers for drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier. J. Control. Release 2015, 211, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherian, A.K.; Rana, A.C.; Jain, S.K. Self-assembled carbohydrate-stabilized ceramic nanoparticles for the parenteral delivery of insulin. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2000, 26, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Shi, J. Drug delivery/imaging multifunctionality of mesoporous silica-based composite nanostructures. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Sant, S.; Wang, B.; Laurent, S.; Sen, T. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (spions): Development, surface modification and applications in chemotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3995–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, M.; Li, H.; Luo, Z.; Kong, J.; Wan, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, H.; Vermorken, A.; van de Ven, W.; et al. Dextran-coated superparamagnetic nanoparticles as potential cancer drug carriers in vitro. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 11155–11162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, L.R.; Gobin, A.M.; Lowery, A.R.; Tam, F.; Drezek, R.A.; Halas, N.J.; West, J.L. Metal nanoshells. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 34, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, B.; Wang, X. Daunorubicin-TiO2 nanocomposites as a “smart” ph-responsive drug delivery system. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Franci, G.; Falanga, A.; Galdiero, S.; Palomba, L.; Rai, M.; Morelli, G.; Galdiero, M. Silver nanoparticles as potential antibacterial agents. Molecules 2015, 20, 8856–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosi, S.; Da Ros, T.; Spalluto, G.; Prato, M. Fullerene derivatives: An attractive tool for biological applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 38, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagona, G.; Tagmatarchis, N. Carbon nanotubes: Materials for medicinal chemistry and biotechnological applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 1789–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geho, D.H.; Lahar, N.; Ferrari, M.; Petricoin, E.F.; Liotta, L.A. Opportunities for nanotechnology-based innovation in tissue proteomics. Biomed. Microdevices 2004, 6, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Qiu, B.; Guo, L. Surface-enhanced electrochemiluminescence of Ru@SiO2 for ultrasensitive detection of carcinoembryonic antigen. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 5966–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ju, Z.; Cao, B.; Gao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Qiu, P.; Xu, H.; Pan, P.; Bao, H.; Wang, L.; et al. Ultrasensitive rapid detection of human serum antibody biomarkers by biomarker-capturing viral nanofibers. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 4475–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalgat, M.K.; Haugland, R.P.; Pollack, J.S.; Swan, S.; Haugland, R.P. Green- and red-fluorescent nanospheres for the detection of cell surface receptors by flow cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods 1998, 219, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.M.; Thaxton, C.S.; Mirkin, C.A. Nanoparticle-based bio-bar codes for the ultrasensitive detection of proteins. Science 2003, 301, 1884–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, C.; Santos-Martinez, M.J.; Radomski, A.; Corrigan, O.I.; Radomski, M.W. Nanoparticles: Pharmacological and toxicological significance. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 150, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Y.; Liao, L.D.; Thakor, N.V.; Tan, M.C. Nanoparticles for molecular imaging. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014, 10, 2641–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickline, S.A.; Lanza, G.M. Nanotechnology for molecular imaging and targeted therapy. Circulation 2003, 107, 1092–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanza, G.M.; Wickline, S.A. Targeted ultrasonic contrast agents for molecular imaging and therapy. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2003, 28, 625–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanza, G.M.; Abendschein, D.R.; Yu, X.; Winter, P.M.; Karukstis, K.K.; Scott, M.J.; Fuhrhop, R.W.; Scherrer, D.E.; Wickline, S.A. Molecular imaging and targeted drug delivery with a novel, ligand-directed paramagnetic nanoparticle technology. Acad. Radiol. 2002, 9, S330–S331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacke, S.; Fischer, S.; Scott, M.J.; Fuhrhop, R.J.; Allen, J.S.; McLean, M.; Winter, P.; Sicard, G.A.; Gaffney, P.J.; Wickline, S.A.; et al. Novel mri contrast agent for molecular imaging of fibrin: Implications for detecting vulnerable plaques. Circulation 2001, 104, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.F.; Jin, P.P.; Tong, Z.; Zhao, Y.P.; Ding, Q.L.; Wang, D.B.; Zhao, G.M.; Jing, D.; Wang, H.L.; Ge, H.L. MR molecular imaging of thrombus: Development and application of a Gd-based novel contrast agent targeting to P-selectin. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2010, 16, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aime, S.; Castelli, D.D.; Crich, S.G.; Gianolio, E.; Terreno, E. Pushing the sensitivity envelope of lanthanide-based magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents for molecular imaging applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapra, P.; Tyagi, P.; Allen, T.M. Ligand-targeted liposomes for cancer treatment. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2005, 2, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Lila, A.S.; Ishida, T.; Kiwada, H. Targeting anticancer drugs to tumor vasculature using cationic liposomes. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, C.; Simoes, S.; Gaspar, R. Paclitaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles: Preparation, physicochemical characterization and in vitro anti-tumoral activity. J. Control. Release 2002, 83, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, D.; Bhadra, S.; Jain, S.; Jain, N.K. A pegylated dendritic nanoparticulate carrier of fluorouracil. Int. J. Pharm. 2003, 257, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnad-Vogt, S.U.; Hofheinz, R.D.; Saussele, S.; Kreil, S.; Willer, A.; Willeke, F.; Pilz, L.; Hehlmann, R.; Hochhaus, A. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and mitomycin C in combination with infusional 5-fluorouracil and sodium folinic acid in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer: Results of a phase II trial. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2005, 16, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, K.; Stone, V.; Tran, C.L.; Kreyling, W.; Borm, P.J. Nanotoxicology. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 61, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberdörster, G.; Oberdörster, E.; Oberdörster, J. Nanotoxicology: An emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabinski, C.; Hussain, S.; Lafdi, K.; Braydich-Stolle, L.; Schlager, J. Effect of particle dimension on biocompatibility of carbon nanomaterials. Carbon 2007, 45, 2828–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, W.; Sun, L.; Aifantis, K.E.; Yu, B.; Fan, Y.; Feng, Q.; Cui, F.; Watari, F. Effects of physicochemical properties of nanomaterials on their toxicity. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2015, 103, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.W.; James, J.T.; McCluskey, R.; Hunter, R.L. Pulmonary toxicity of single-wall carbon nanotubes in mice 7 and 90 days after intratracheal instillation. Toxicol. Sci. 2004, 77, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, Y.; Horie, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Shinohara, N.; Shimada, M. Inhalation toxicity assessment of carbon-based nanoparticles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Singh, S.; Sahu, J.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, M.R. Ceramic nanoparticles: Recompense, cellular uptake and toxicity concerns. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radomski, A.; Jurasz, P.; Alonso-Escolano, D.; Drews, M.; Morandi, M.; Malinski, T.; Radomski, M.W. Nanoparticle-induced platelet aggregation and vascular thrombosis. Br. J. Pharm. 2005, 146, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.; Tian, F.; Ozkan, C.S.; Wang, M.; Gao, H. Effect of single wall carbon nanotubes on human HEK293 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 155, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alazzam, A.; Mfoumou, E.; Stiharu, I.; Kassab, A.; Darnel, A.; Yasmeen, A.; Sivakumar, N.; Bhat, R.; Al Moustafa, A.E. Identification of deregulated genes by single wall carbon-nanotubes in human normal bronchial epithelial cells. Nanomedicine 2010, 6, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, N.R.; Amara, S.; Mrad, I.; Ben-Slama, I.; Jeljeli, M.; Omri, K.; El Ghoul, J.; El Mir, L.; Rhouma, K.B.; Abdelmelek, H.; et al. Subacute toxicity of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in male rats: Emotional behavior and pathophysiological examination. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 8728–8737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, R.; Raza, S.; Yadav, A.; Kushwaha, P.; Flora, S.J. Effects of sub-acute exposure to TiO2, ZnO and Al2O3 nanoparticles on oxidative stress and histological changes in mouse liver and brain. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 37, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, X. Cytotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in rat neuroglia cells. Brain Inj. 2013, 27, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Shi, T.; Li, X.; Zeng, S.; Yin, L.; Pu, Y. Effects of nano-MnO2 on dopaminergic neurons and the spatial learning capability of rats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7918–7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lademann, J.; Weigmann, H.; Rickmeyer, C.; Barthelmes, H.; Schaefer, H.; Mueller, G.; Sterry, W. Penetration of titanium dioxide microparticles in a sunscreen formulation into the horny layer and the follicular orifice. Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol. 1999, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trop, M.; Novak, M.; Rodl, S.; Hellbom, B.; Kroell, W.; Goessler, W. Silver-coated dressing acticoat caused raised liver enzymes and argyria-like symptoms in burn patient. J. Trauma 2006, 60, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemmar, A.; Yuvaraju, P.; Beegam, S.; Yasin, J.; Dhaheri, R.A.; Fahim, M.A.; Ali, B.H. In vitro platelet aggregation and oxidative stress caused by amorphous silica nanoparticles. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 7, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, N.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.B.; Yu, Y.B.; Zhou, X.Q.; Sun, Z.W. Exposure to silica nanoparticles causes reversible damage of the spermatogenic process in mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.; Saei, A.A.; Behzadi, S.; Panahifar, A.; Mahmoudi, M. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for delivery of therapeutic agents: Opportunities and challenges. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 1449–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkilany, A.M.; Murphy, C.J. Toxicity and cellular uptake of gold nanoparticles: What we have learned so far? J. Nanopart. Res. 2010, 12, 2313–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, L.; Chen, R.; Zhao, L.; Shi, X.; Bai, R.; Long, D.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Y.; Chang, Y.Z.; Chen, C. Silver nanoparticles activate endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling pathway in cell and mouse models: The role in toxicity evaluation. Biomaterials 2015, 61, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Stayton, I.; Huang, Y.-W.; Zhou, X.-D.; Ma, Y. Cytotoxicity and cell membrane depolarization induced by aluminum oxide nanoparticles in human lung epithelial cells A549. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2008, 90, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, B.; Cormier, S.A. Copper oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in airway epithelial cells. Toxicol. In vitro 2009, 23, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manke, A.; Wang, L.; Rojanasakul, Y. Mechanisms of nanoparticle-induced oxidative stress and toxicity. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Ghosh, M.; Sil, P.C. Nanotoxicity: Oxidative stress mediated toxicity of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaapen, A.M.; Borm, P.J.; Albrecht, C.; Schins, R.P. Inhaled particles and lung cancer. Part A: Mechanisms. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 109, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risom, L.; Møller, P.; Loft, S. Oxidative stress-induced DNA damage by particulate air pollution. Mutat. Res. 2005, 592, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, H.J.; Choi, J. Oxidative stress of ceo2 nanoparticles via p38-Nrf-2 signaling pathway in human bronchial epithelial cell, Beas-2B. Toxicol. Lett. 2009, 187, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avalos, A.; Haza, A.I.; Mateo, D.; Morales, P. Cytotoxicity and ros production of manufactured silver nanoparticles of different sizes in hepatoma and leukemia cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2014, 34, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misawa, M.; Takahashi, J. Generation of reactive oxygen species induced by gold nanoparticles under X-ray and UV irradiations. Nanomedicine 2011, 7, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.-J.; Park, K. Oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory responses induced by silica nanoparticles in vitro and in vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 2009, 184, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Sun, P.; Bao, Y.; Liu, J.; An, L. Cytotoxicity of single-walled carbon nanotubes on PC12 cells. Toxicol. In vitro 2011, 25, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhornik, E.V.; Baranova, L.A.; Strukova, A.M.; Loiko, E.N.; Volotovskii, I.D. ROS induction and structural modification in human lymphocyte membrane under the influence of carbon nanotubes. Biofizika 2012, 57, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Manshian, B.; Jenkins, G.J.S.; Griffiths, S.M.; Williams, P.M.; Maffeis, T.G.G.; Wright, C.J.; Doak, S.H. Nanogenotoxicology: The DNA damaging potential of engineered nanomaterials. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3891–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarifi, S.; Ali, D.; Alkahtani, S. Nanoalumina induces apoptosis by impairing antioxidant enzyme systems in human hepatocarcinoma cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 3751–3760. [Google Scholar]

- Al Gurabi, M.A.; Ali, D.; Alkahtani, S.; Alarifi, S. In vitro DNA damaging and apoptotic potential of silver nanoparticles in swiss albino mice. Onco Targets Ther. 2015, 8, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sliwinska, A.; Kwiatkowski, D.; Czarny, P.; Milczarek, J.; Toma, M.; Korycinska, A.; Szemraj, J.; Sliwinski, T. Genotoxicity and cytotoxicity of ZnO and Al2O3 nanoparticles. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2015, 25, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.J.; Zou, L.; Hartono, D.; Ong, C.N.; Bay, B.H.; Lanry Yung, L.Y. Gold nanoparticles induce oxidative damage in lung fibroblasts in vitro. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.; Davoren, M.; Boertz, J.; Schins, R.; Hoffmann, E.; Dopp, E. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and DNA-adduct formation but not DNA-breakage in human lung cells. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Xu, Y.; Huang, C.-C.; Ma, Y.; Shannon, K.B.; Chen, D.-R.; Huang, Y.-W. Toxicity of nano-and micro-sized ZnO particles in human lung epithelial cells. J. Nanopart. Res. 2009, 11, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, H.L.; Cronholm, P.; Gustafsson, J.; Moller, L. Copper oxide nanoparticles are highly toxic: A comparison between metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 1726–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, D.P. Cancer. P53, guardian of the genome. Nature 1992, 358, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, A.O.; Brown, S.E.; Szyf, M.; Maysinger, D. Quantum dot-induced epigenetic and genotoxic changes in human breast cancer cells. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 86, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeng, H.A.; Swanson, J. Toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles in mammalian cells. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2006, 41, 2699–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamed, M.; Posgai, R.; Gorey, T.J.; Nielsen, M.; Hussain, S.M.; Rowe, J.J. Silver nanoparticles induced heat shock protein 70, oxidative stress and apoptosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 242, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-W.; Wu, C.-H.; Aronstam, R.S. Toxicity of transition metal oxide nanoparticles: Recent insights from in vitro studies. Materials 2010, 3, 4842–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baktur, R.; Patel, H.; Kwon, S. Effect of exposure conditions on SWCNT-induced inflammatory response in human alveolar epithelial cells. Toxicol. In vitro 2011, 25, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouzier, D.; Follot, S.; Gentilhomme, E.; Flahaut, E.; Arnaud, R.; Dabouis, V.; Castellarin, C.; Debouzy, J.C. Carbon nanotubes induce inflammation but decrease the production of reactive oxygen species in lung. Toxicology 2010, 272, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rouse, J.G.; Yang, J.; Barron, A.R.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A. Fullerene-based amino acid nanoparticle interactions with human epidermal keratinocytes. Toxicol. In vitro 2006, 20, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, C.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Tan, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, S.; Liu, S.; et al. Carbon nanotubes provoke inflammation by inducing the pro-inflammatory genes IL-1β and IL-6. Gene 2012, 493, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turabekova, M.; Rasulev, B.; Theodore, M.; Jackman, J.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J. Immunotoxicity of nanoparticles: A computational study suggests that CNTs and C60 fullerenes might be recognized as pathogens by toll-like receptors. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 3488–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrovolskaia, M.A.; Aggarwal, P.; Hall, J.B.; McNeil, S.E. Preclinical studies to understand nanoparticle interaction with the immune system and its potential effects on nanoparticle biodistribution. Mol. Pharm. 2008, 5, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanan-Khan, A.; Szebeni, J.; Savay, S.; Liebes, L.; Rafique, N.M.; Alving, C.R.; Muggia, F.M. Complement activation following first exposure to pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): Possible role in hypersensitivity reactions. Ann. Oncol. 2003, 14, 1430–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebeni, J.; Alving, C.R.; Rosivall, L.; Bunger, R.; Baranyi, L.; Bedocs, P.; Toth, M.; Barenholz, Y. Animal models of complement-mediated hypersensitivity reactions to liposomes and other lipid-based nanoparticles. J. Liposome Res. 2007, 17, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolnik, B.S.; González-Fernández, Á.; Sadrieh, N.; Dobrovolskaia, M.A. Nanoparticles and the immune system. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.T.; van der Vlies, A.J.; Simeoni, E.; Angeli, V.; Randolph, G.J.; O’Neil, C.P.; Lee, L.K.; Swartz, M.A.; Hubbell, J.A. Exploiting lymphatic transport and complement activation in nanoparticle vaccines. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fifis, T.; Gamvrellis, A.; Crimeen-Irwin, B.; Pietersz, G.A.; Li, J.; Mottram, P.L.; McKenzie, I.F.; Plebanski, M. Size-dependent immunogenicity: Therapeutic and protective properties of nano-vaccines against tumors. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 3148–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottram, P.L.; Leong, D.; Crimeen-Irwin, B.; Gloster, S.; Xiang, S.D.; Meanger, J.; Ghildyal, R.; Vardaxis, N.; Plebanski, M. Type 1 and 2 immunity following vaccination is influenced by nanoparticle size: Formulation of a model vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallach, D.; Kang, T.-B.; Kovalenko, A. Concepts of tissue injury and cell death in inflammation: A historical perspective. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljak-Blaži, M.; Jaganjac, M.; Žarković, N. Cell Oxidative Stress: Risk of Metal Nanoparticles; CRC Press Taylor: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.J.E.; Muralikrishnan, S.; Ng, C.-T.; Yung, L.-Y.L.; Bay, B.-H. Nanoparticle-induced pulmonary toxicity. Exp.Biol. Med. 2010, 235, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.; Tresini, M. Oxidative stress and gene regulation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 463–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhang, X.; Young, H.A.; Mao, Y.; Shi, X. Chromium(VI)-induced nuclear factor-κB activation in intact cells via free radical reactions. Carcinogenesis 1995, 16, 2401–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, J.D.; Baugh, J.A. The significance of nanoparticles in particle-induced pulmonary fibrosis. McGill J. Med. 2008, 11, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Monteiller, C.; Tran, L.; MacNee, W.; Faux, S.; Jones, A.; Miller, B.; Donaldson, K. The pro-inflammatory effects of low-toxicity low-solubility particles, nanoparticles and fine particles, on epithelial cells in vitro: The role of surface area. Occup. Environ. Med. 2007, 64, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, A.K.; Timblin, C.R.; Shukla, A.; Rincón, M.; Mossman, B.T. Activation of NF-κB-dependent gene expression by silica in lungs of luciferase reporter mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2002, 282, L968–L975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujalté, I.; Passagne, I.; Brouillaud, B.; Tréguer, M.; Durand, E.; Ohayon-Courtès, C.; L’Azou, B. Cytotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by different metallic nanoparticles on human kidney cells. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2011, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Samet, J.M.; Peden, D.B.; Bromberg, P.A. Phosphorylation of p65 is required for zinc oxide nanoparticle–induced interleukin 8 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, E.; Baarine, M.; Pelloux, S.; Riedinger, J.-M.; Frouin, F.; Tourneur, Y.; Lizard, G. Iron nanoparticles increase 7-ketocholesterol-induced cell death, inflammation, and oxidation on murine cardiac hl1-nb cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, U.C.; Hansen, J.S.; Samuelsen, M.; Alberg, T.; Marioara, C.D.; Løvik, M. Single-walled and multi-walled carbon nanotubes promote allergic immune responses in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 109, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, M.; Forman, H.J. Redox signaling and the map kinase pathways. BioFactors 2003, 17, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.-J.; Yi, J.; Chung, K.-H.; Ryu, D.-Y.; Choi, J.; Park, K. Oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in cultured BEAS-2B cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 180, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.; Roh, J.-Y.; Eom, H.-J.; Choi, J.-Y.; Hyun, J.; Choi, J. Oxidative stress-related PMK-1 p38 mapk activation as a mechanism for toxicity of silver nanoparticles to reproduction in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2012, 31, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Sun, J. Endothelial cells dysfunction induced by silica nanoparticles through oxidative stress via jnk/p53 and NF-κB pathways. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8198–8209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacurari, M.; Yin, X.J.; Zhao, J.; Ding, M.; Leonard, S.S.; Schwegler-Berry, D.; Ducatman, B.S.; Sbarra, D.; Hoover, M.D.; Castranova, V. Raw single-wall carbon nanotubes induce oxidative stress and activate MAPKs, AP-1, NF-κB, and Akt in normal and malignant human mesothelial cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, R.; Parashar, V.; Chauhan, L.K.S.; Shanker, R.; Das, M.; Tripathi, A.; Dwivedi, P.D. Mechanism of uptake of ZnO nanoparticles and inflammatory responses in macrophages require PI3K mediated mapks signaling. Toxicol. In vitro 2014, 28, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Yu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Geng, W.; Jiang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Z. Silica nanoparticles induce autophagy and endothelial dysfunction via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Int J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 5131–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niki, E. Action of ascorbic acid as a scavenger of active and stable oxygen radicals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 1119s–1124s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Ge, Y.; Ma, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Anti-leukemia activity of PVP-coated silver nanoparticles via generation of reactive oxygen species and release of silver ions. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 7884–7894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamed, M.; Akhtar, M.J.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Ahmad, J.; Musarrat, J.; Al-Khedhairy, A.A.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Alrokayan, S.A. Oxidative stress mediated apoptosis induced by nickel ferrite nanoparticles in cultured a549 cells. Toxicology 2011, 283, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posgai, R.; Cipolla-McCulloch, C.B.; Murphy, K.R.; Hussain, S.M.; Rowe, J.J.; Nielsen, M.G. Differential toxicity of silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles on drosophila melanogaster development, reproductive effort, and viability: Size, coatings and antioxidants matter. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, H.; Iwahashi, H.; Endoh, S.; Nishio, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Hagihara, Y.; Horie, M. Ascorbic acid attenuates acute pulmonary oxidative stress and inflammation caused by zinc oxide nanoparticles. J. Occup. Health 2015, 57, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Sil, P.C. Iron oxide nanoparticles mediated cytotoxicity via PI3K/Akt pathway: Role of quercetin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 71, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Esquivel, A.E.; Charles-Nino, C.L.; Pacheco-Moises, F.P.; Ortiz, G.G.; Jaramillo-Juarez, F.; Rincon-Sanchez, A.R. Beneficial effects of quercetin on oxidative stress in liver and kidney induced by titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in rats. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2015, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevanovic, M.; Bracko, I.; Milenkovic, M.; Filipovic, N.; Nunic, J.; Filipic, M.; Uskokovic, D.P. Multifunctional PLGA particles containing poly(l-glutamic acid)-capped silver nanoparticles and ascorbic acid with simultaneous antioxidative and prolonged antimicrobial activity. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthington, K.L.; Adamcakova-Dodd, A.; Wongrakpanich, A.; Mudunkotuwa, I.A.; Mapuskar, K.A.; Joshi, V.B.; Allan Guymon, C.; Spitz, D.R.; Grassian, V.H.; Thorne, P.S.; et al. Chitosan coating of copper nanoparticles reduces in vitro toxicity and increases inflammation in the lung. Nanotechnology 2013, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Jadaun, A.; Arora, V.; Sinha, R.K.; Biyani, N.; Jain, V.K. In vitro toxicity assessment of chitosan oligosaccharide coated iron oxide nanoparticles. Toxicol. Rep. 2015, 2, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Huang, S.; Yu, K.J.; Clyne, A.M. Dextran and polymer polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating reduce both 5 and 30 nm iron oxide nanoparticle cytotoxicity in 2D and 3D cell culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 5554–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonthaler, H.B.; Guinea-Viniegra, J.; Wagner, E.F. Targeting inflammation by modulating the Jun/AP-1 pathway. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, i109–i112. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khanna, P.; Ong, C.; Bay, B.H.; Baeg, G.H. Nanotoxicity: An Interplay of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Cell Death. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 1163-1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5031163

Khanna P, Ong C, Bay BH, Baeg GH. Nanotoxicity: An Interplay of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Cell Death. Nanomaterials. 2015; 5(3):1163-1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5031163

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhanna, Puja, Cynthia Ong, Boon Huat Bay, and Gyeong Hun Baeg. 2015. "Nanotoxicity: An Interplay of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Cell Death" Nanomaterials 5, no. 3: 1163-1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano5031163