Towards Water-Free Tellurite Glass Fiber for 2–5 μm Nonlinear Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Silica (SiO2 based) | Tellurite (TeO2 based) | Fluoride (ZrF4 or AlF3 based) | Chalcogenide (chalcogen S, Se, Te based) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refractive index n at 1.55 µm | 1.46 | 2–2.2 | 1.5–1.6 | 2.3–3 |

| Nonlinear refractive index n2 (× 10−20 m2/W) | 2.5 | 20–50 | 2–3 | 100–1000 |

| λ0, zero dispersion wavelength of material (µm) | ~1.3 | ~2 | ~1.7 | >5 |

| IR longwave transmission limit | up to 3 µm | 6–7 µm | 7–8 µm | 12–16 µm |

| Thermal stability for fiber drawing | excellent | good | poor | good |

| Viscosity around fiber drawing temperature | flat | steep | steep | flat |

| Durability in environment | excellent | good | poor, hygroscopic | good |

| Toxicity | safe | safe | relatively high | relatively high |

2. Experimental Section

3. Results and Discussion

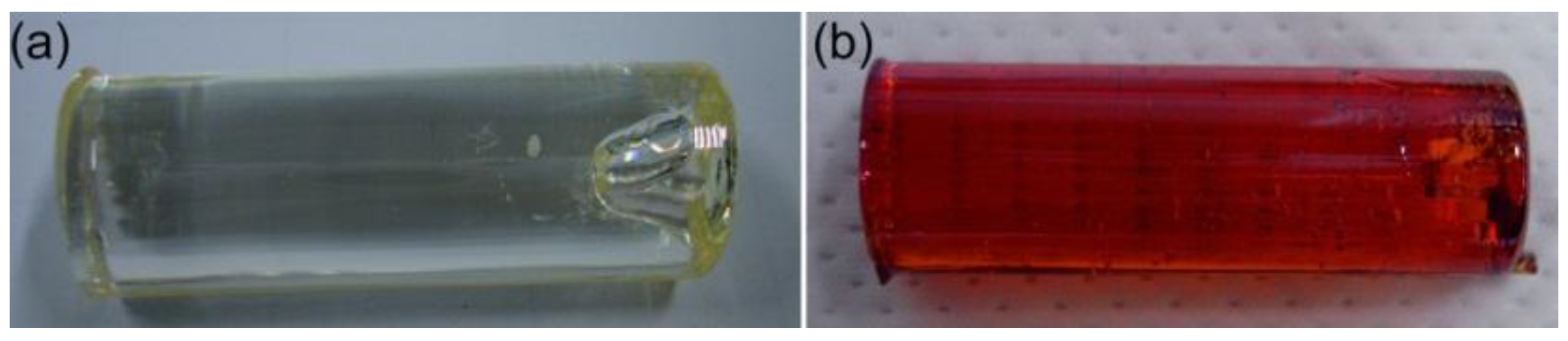

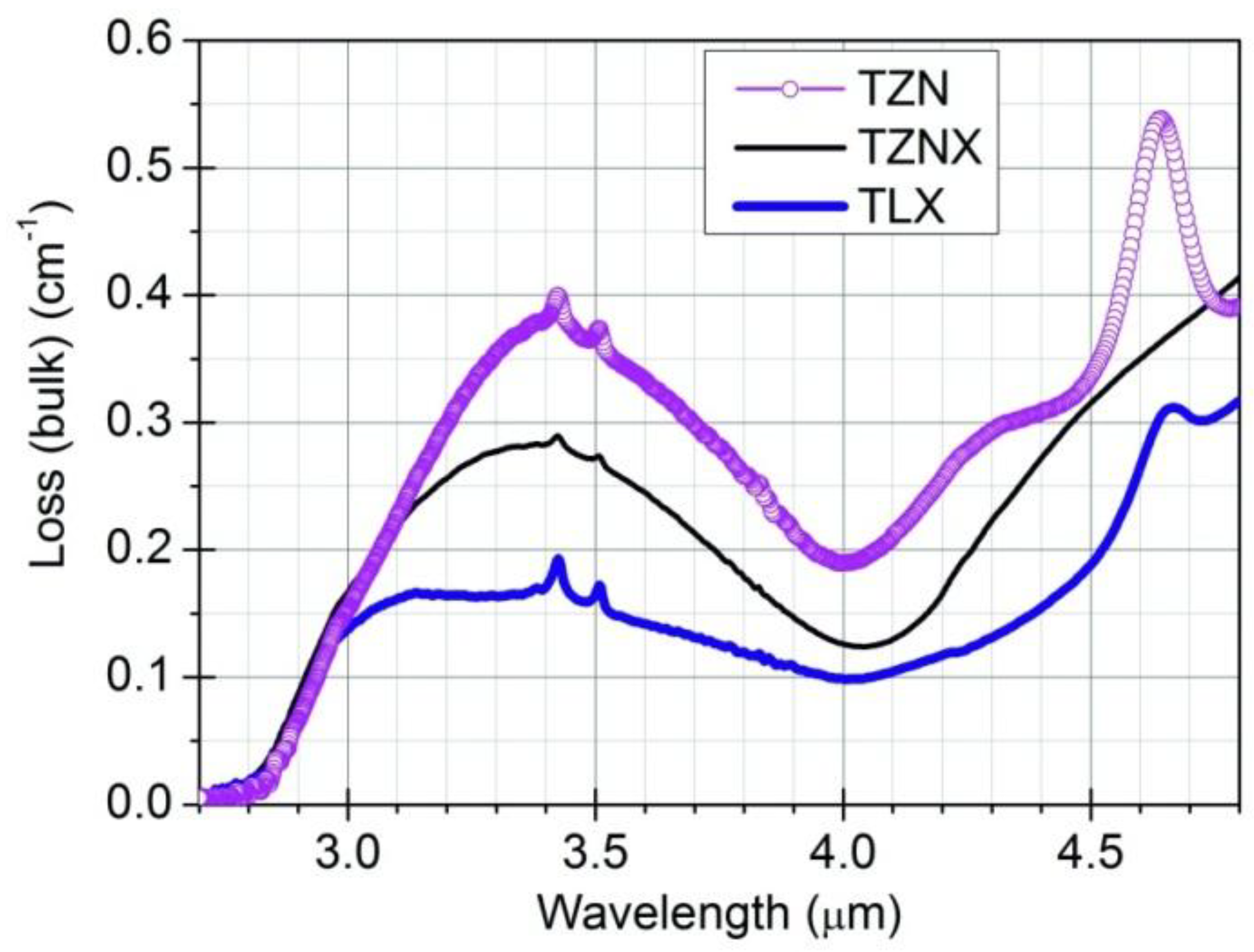

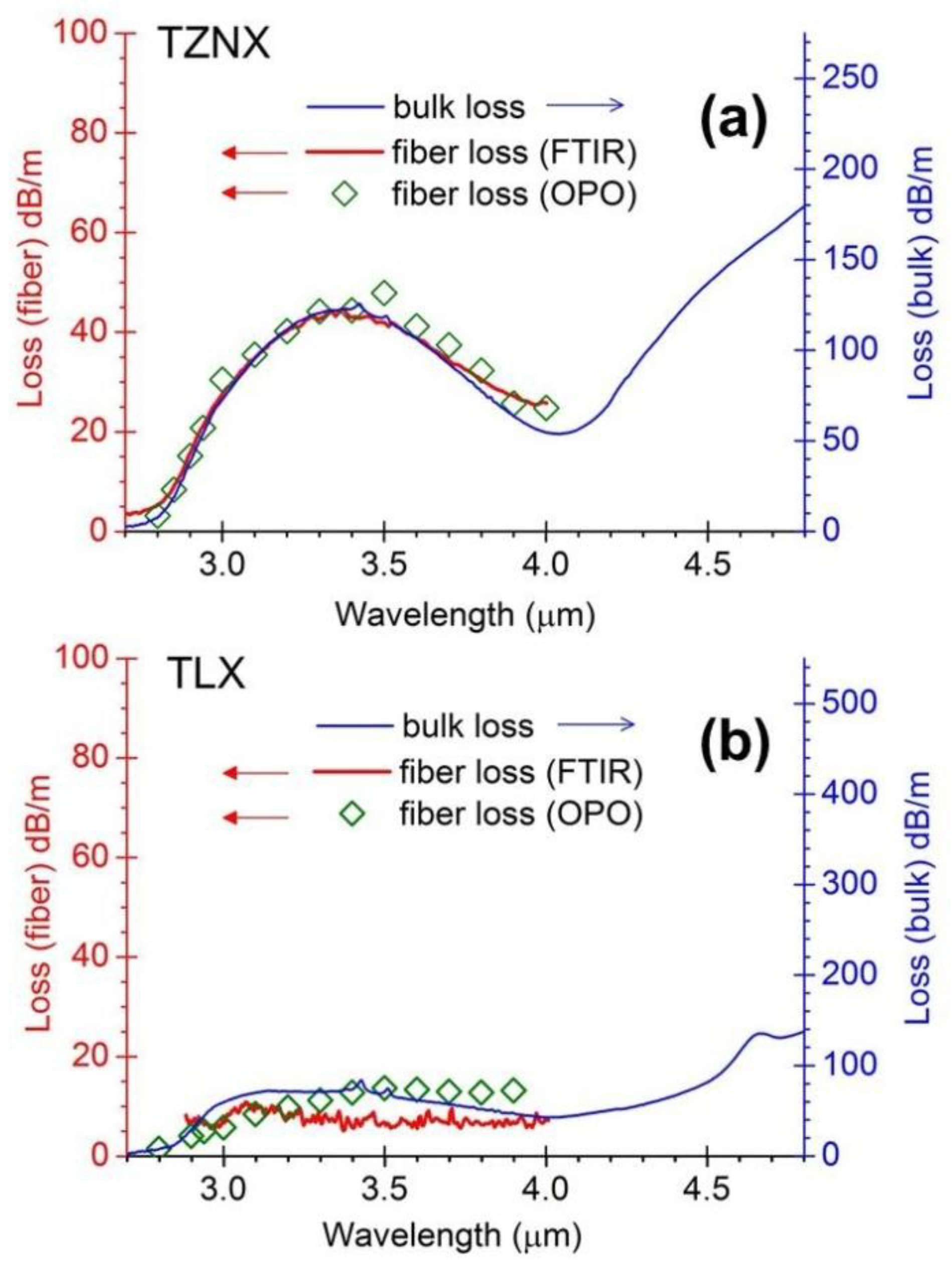

3.1. OH-Induced Attenuation in Dehydrated Tellurite Bulks and Unclad Fiber

3.2. Refractive Index, Dispersion and Nonlinearity of Dehydrated Tellurite Glasses

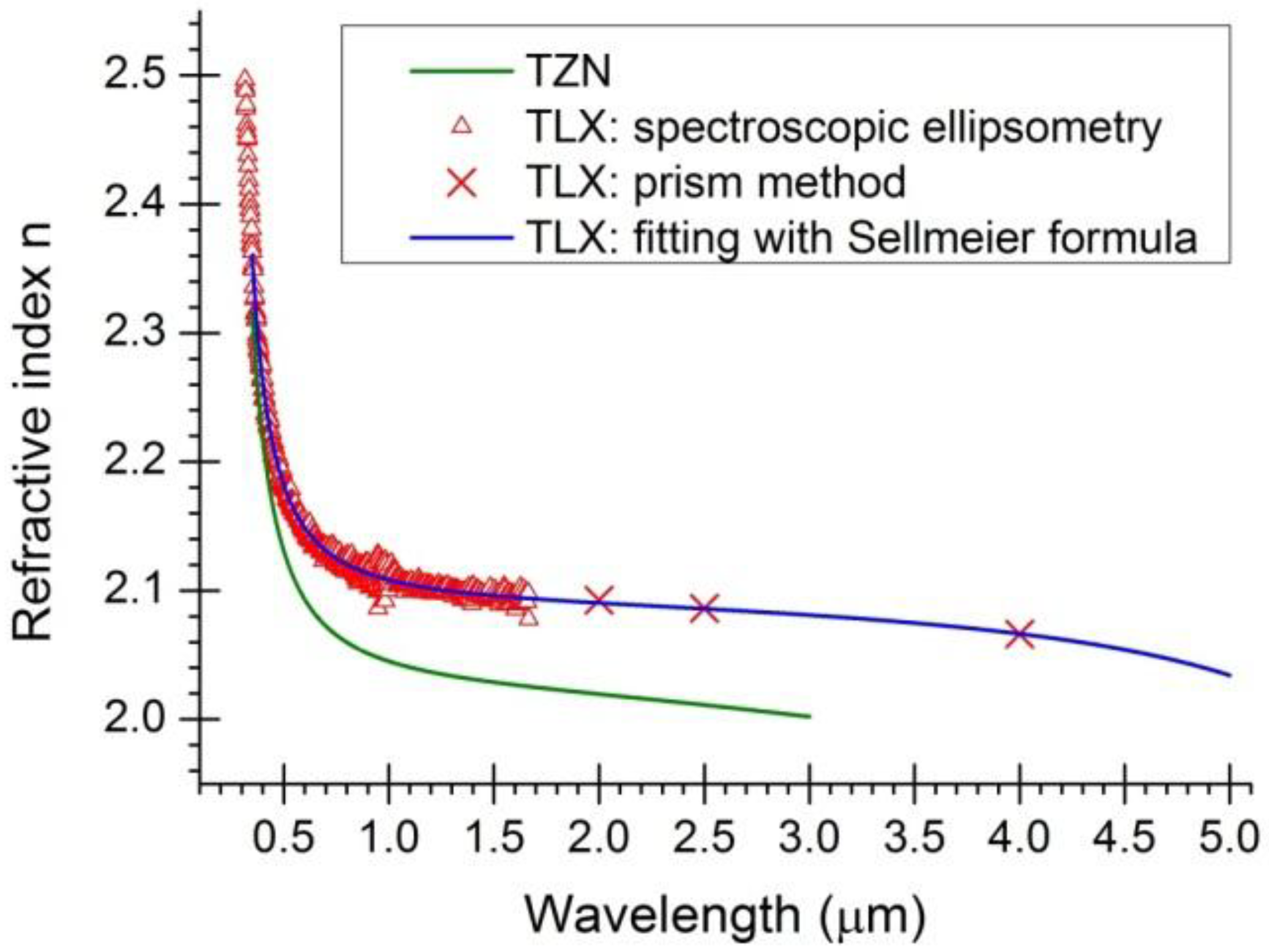

, in which λ is wavelength in micrometers, and Bi (i = 1, 2, 3) and Ci (i = 1, 2, 3) are the coefficients of the equation, for the TLX glass, the fitted six coefficients are seen in Table 2. Figure 5 shows the refractive index and material dispersion curves of TLX glass from 0.3 to 5µm. The refractive index curve of TZN glass was also plotted in Figure 5 in the range of 0.4–3 µm, according to the Sellmeier parameters of similar tellurite glasses [11]. Because the composition of TZN is very close to TZNX, their index and dispersion curves should be very close to each other.

, in which λ is wavelength in micrometers, and Bi (i = 1, 2, 3) and Ci (i = 1, 2, 3) are the coefficients of the equation, for the TLX glass, the fitted six coefficients are seen in Table 2. Figure 5 shows the refractive index and material dispersion curves of TLX glass from 0.3 to 5µm. The refractive index curve of TZN glass was also plotted in Figure 5 in the range of 0.4–3 µm, according to the Sellmeier parameters of similar tellurite glasses [11]. Because the composition of TZN is very close to TZNX, their index and dispersion curves should be very close to each other.

| Sellmeier coefficients Glass | B1 | C1 | B2 | C2 | B3 | C3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLX | 1.212 | 6.068 × 10−2 | 2.157 | 7.068 × 10−4 | 0.1891 | 45.19 |

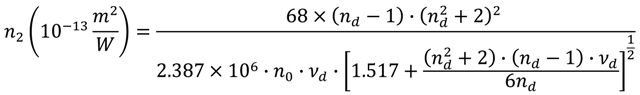

, nd, nF, and nC are the refractive indices at 587.6 nm, 486.1 nm and 656.3 nm respectively), and n0 is the refractive index at the interesting wavelength, respectively. The n2 of the TLX glass is calculated to be 5.0 × 10−19 m2/W, about 20 times higher than that of silica glass and also higher than TZN glass (1.7 × 10−19 m2/W [12]) and the lead silicate glass Schott SF57 (4.1 × 1019 m2/W [24]).

, nd, nF, and nC are the refractive indices at 587.6 nm, 486.1 nm and 656.3 nm respectively), and n0 is the refractive index at the interesting wavelength, respectively. The n2 of the TLX glass is calculated to be 5.0 × 10−19 m2/W, about 20 times higher than that of silica glass and also higher than TZN glass (1.7 × 10−19 m2/W [12]) and the lead silicate glass Schott SF57 (4.1 × 1019 m2/W [24]).

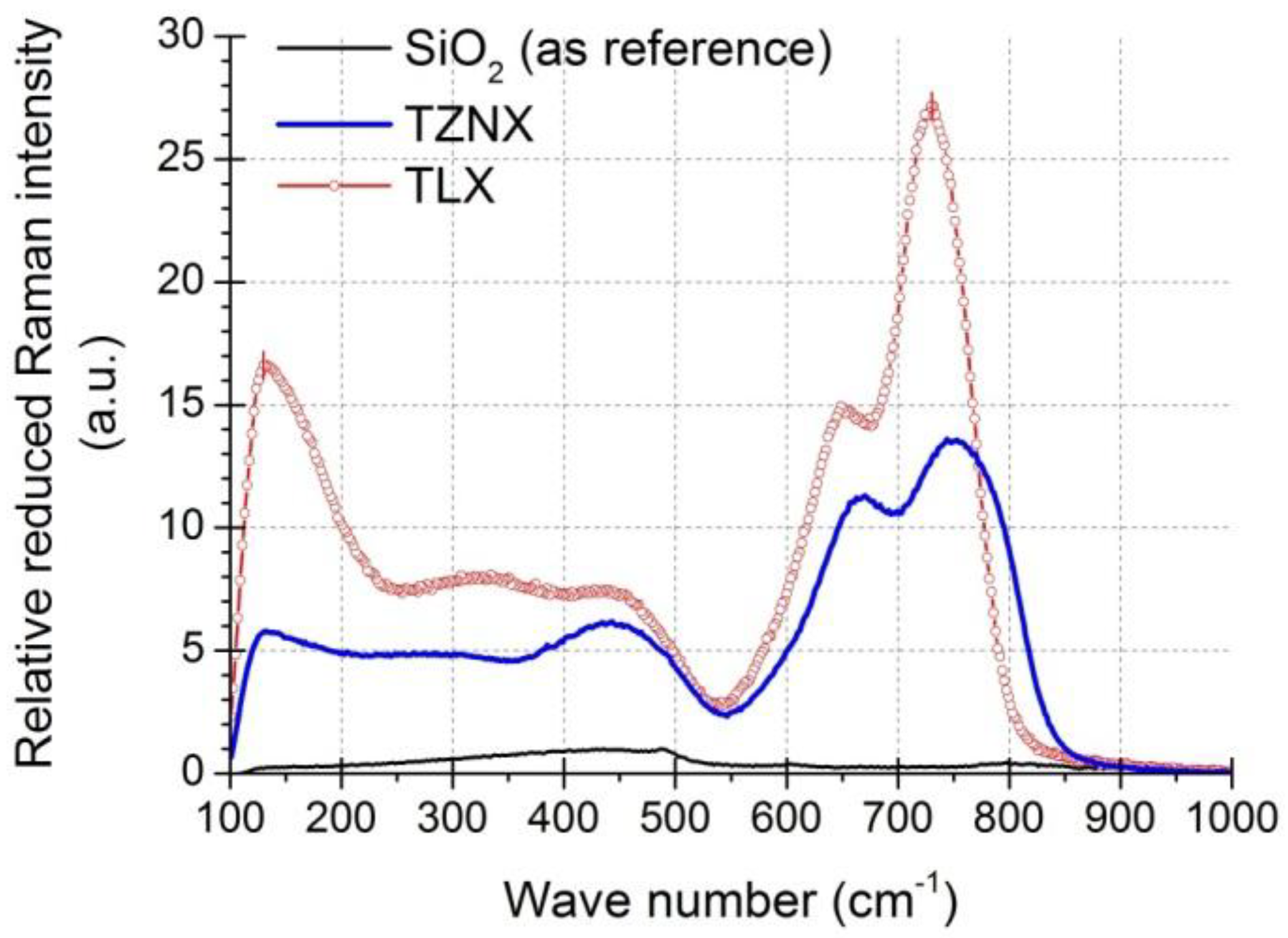

3.3. Raman Gain Coefficients of Dehydrated Tellurite Glasses

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schliesser, A.; Picqué, N.; Hänsch, T.W. Mid-infrared frequency combs. Nature Photon. 2012, 6, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, P.S.J. Photonic crystal fibers. Science 2003, 299, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranka, J.K.; Windeler, R.S.; Stentz, A.J. Visible continuum generation in air-silica microstructure optical fibers with anomalous dispersion at 800 nm. Opt. Lett. 2000, 25, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serkland, D.K.; Kumar, P. Tunable fiber-optic parametric oscillator. Opt. Lett. 1999, 24, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundiff, S.T.; Ye, J. Colloquium: Femtosecond optical frequency combs. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szigeti, B. Polarisability and dielectric constant of ionic crystals. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1949, 45, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniort, J.Y.; Brehm, C.; DuPont, P.H.; Guignot, D.; Le Sergent, C. Infrared Glass Optical Fibers for 4 and 10 Micron Bands. In Proceedings of the 6th European Conference on Optical Communication, York, UK, 16–19 September 1980; pp. 61–64.

- Poulain, M.; Poulain, M.; Lucas, J.; Brun, P. Verres fluores au tetrafluorure de zirconium proprietes optiques d’un verre dope au Nd3+. Mat. Res. Bull. 1975, 10, 243–246. (in French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapany, N.S.; Simms, R.J. Recent developments of infrared fiber optics. Infrared Phys. 1965, 5, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.S.; Vogel, E.M.; Snitzer, E. Tellurite glass: A new candidate for fiber devices. Opt. Mater. 1994, 3, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, G. Sellmeier coefficients and chromatic dispersions for some tellurite glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1995, 78, 2828–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Loh, W.H.; Flanagan, J.C.; Camerlingo, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Petropoulos, P.; Horak, P.; Frampton, K.E.; White, N.M.; Price, J.H.V.; et al. Single-mode tellurite glass holey fiber with extremely large mode area for infrared nonlinear applications. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 13651–13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Flanagan, J.C.; Frampton, K.E.; Petropoulos, P.; White, N.M.; Price, J.H.V.; Loh, W.H.; Rutt, H.N.; Richardson, D.J. Developing single-mode tellurite glass holey fiber for infrared nonlinear applications. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2008, 55, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, P.W.; Carter, S.F.; Williams, J.R.; Beales, K.J.; Parker, J.M. OH-absorption in fluoride glass infra-red fibres. Electron. Lett. 1984, 20, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Tanabe, S.; Hanada, T. Hydroxyl groups in erbium-doped germanotellurite glasses. J. Non-Crystall. Solids 2001, 281, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbach, O.; Fabian, H.; Grzesik, U.; Haken, U.; Heitmann, W. Analysis of OH absorption bands in synthetic silica. J. Non-Crystall. Solids 1996, 203, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domachuk, P.; Wolchover, N.A.; Cronin-Golomb, M.; Wang, A.; George, A.K.; Cordeiro, C.M.B.; Knight, J.C.; Omenetto, F.G. Over 4000 nm bandwidth of mid-IR supercontinuum generation in sub-centimeter segments of highly nonlinear tellurite PCFs. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 7161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H.; Kuan, K.; Oermann, M.R.; Knight, K.; Monro, T.M. Extruded tellurite glass and fibers with low OH content for mid-infrared applications. Opt. Mater. Express 2012, 2, 432–442. [Google Scholar]

- Comyns, A.E. Fluoride glasses; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, S.; MacChesney, J.B.; Walker, K. An overview of the modified chemical vapor deposition (MCVD) process and performance. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 1982, 18, 459–476. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, M.D.; Miller, C.A.; Furniss, D.; Tikhomirov, V.K.; Seddon, A.B. Fluorotellurite glasses with improved mid-infrared transmission. J. Non-Crystall. Solids 2003, 331, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Lemay, H.E.; Burnsten, B.E. Chemistry—the Central Science., 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 1017. [Google Scholar]

- Boling, N.L.; Glass, A.J.; Owyoung, A. Empirical relationships for predicting non-linear refractive-index changes in optical solids. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1978, QE-14, 601–608. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang, K.M.; Frampton, K.; Monro, T.M.; Moore, R.; Tucknott, J.; Hewak, D.W.; Richardson, D.J.; Rutt, H.N. Extruded single-mode non-silica glass holey optical fibres. Electron. Lett. 2002, 38, 546–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Feng, X.; Horak, P.; Chen, K.K.; Teh, P.S.; Alam, S.-U.; Loh, W.H.; Richardson, D.J.; Ibsen, M. 1.06 µm picosecond pulsed, normal dispersion pumping for generating efficient broadband infrared supercontinuum in meter-length single-mode tellurite holey fiber with high Raman gain coefficient. J. Lightwave Technol. 2011, 29, 3461–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, X.; Shi, J.; Segura, M.; White, N.M.; Kannan, P.; Calvez, L.; Zhang, X.; Brilland, L.; Loh, W.H. Towards Water-Free Tellurite Glass Fiber for 2–5 μm Nonlinear Applications. Fibers 2013, 1, 70-81. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib1030070

Feng X, Shi J, Segura M, White NM, Kannan P, Calvez L, Zhang X, Brilland L, Loh WH. Towards Water-Free Tellurite Glass Fiber for 2–5 μm Nonlinear Applications. Fibers. 2013; 1(3):70-81. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib1030070

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Xian, Jindan Shi, Martha Segura, Nicolas M. White, Pradeesh Kannan, Laurent Calvez, Xianghua Zhang, Laurent Brilland, and Wei H. Loh. 2013. "Towards Water-Free Tellurite Glass Fiber for 2–5 μm Nonlinear Applications" Fibers 1, no. 3: 70-81. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib1030070