A Comparison of Competences for Healthcare Professions in Europe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The recommendations for the minimum requirements of the EU directive [4].

- The formulations of the academic proposals for CBE in healthcare sciences.

- The perception by practitioners of the framework proposals for pharmacy and medicine. (This step has not to our knowledge been undertaken in dentistry).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Recommendations for Minimum Requirements of the European Directive

2.2. The Formulations of the Academic Proposals for CBE in Healthcare Sciences

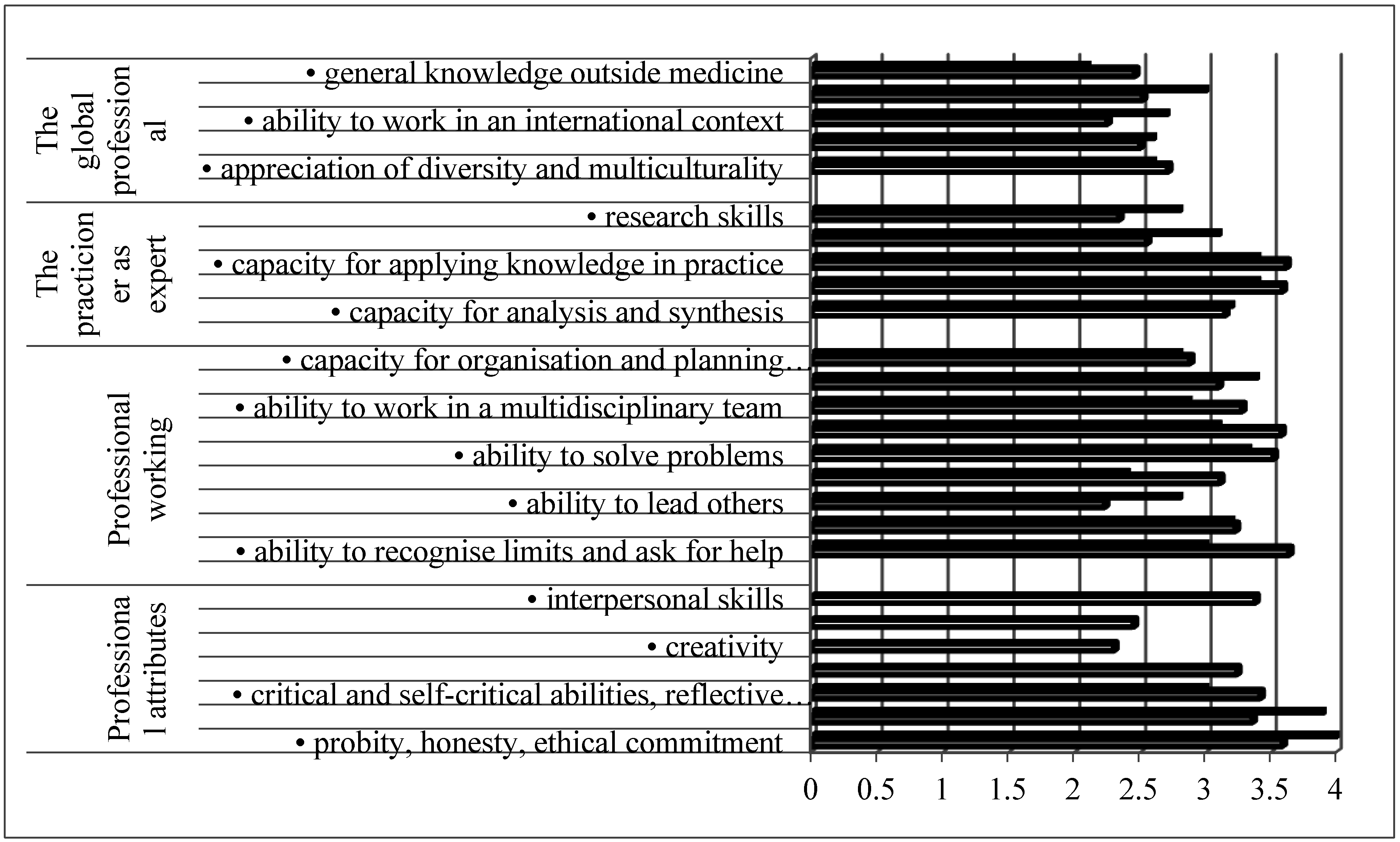

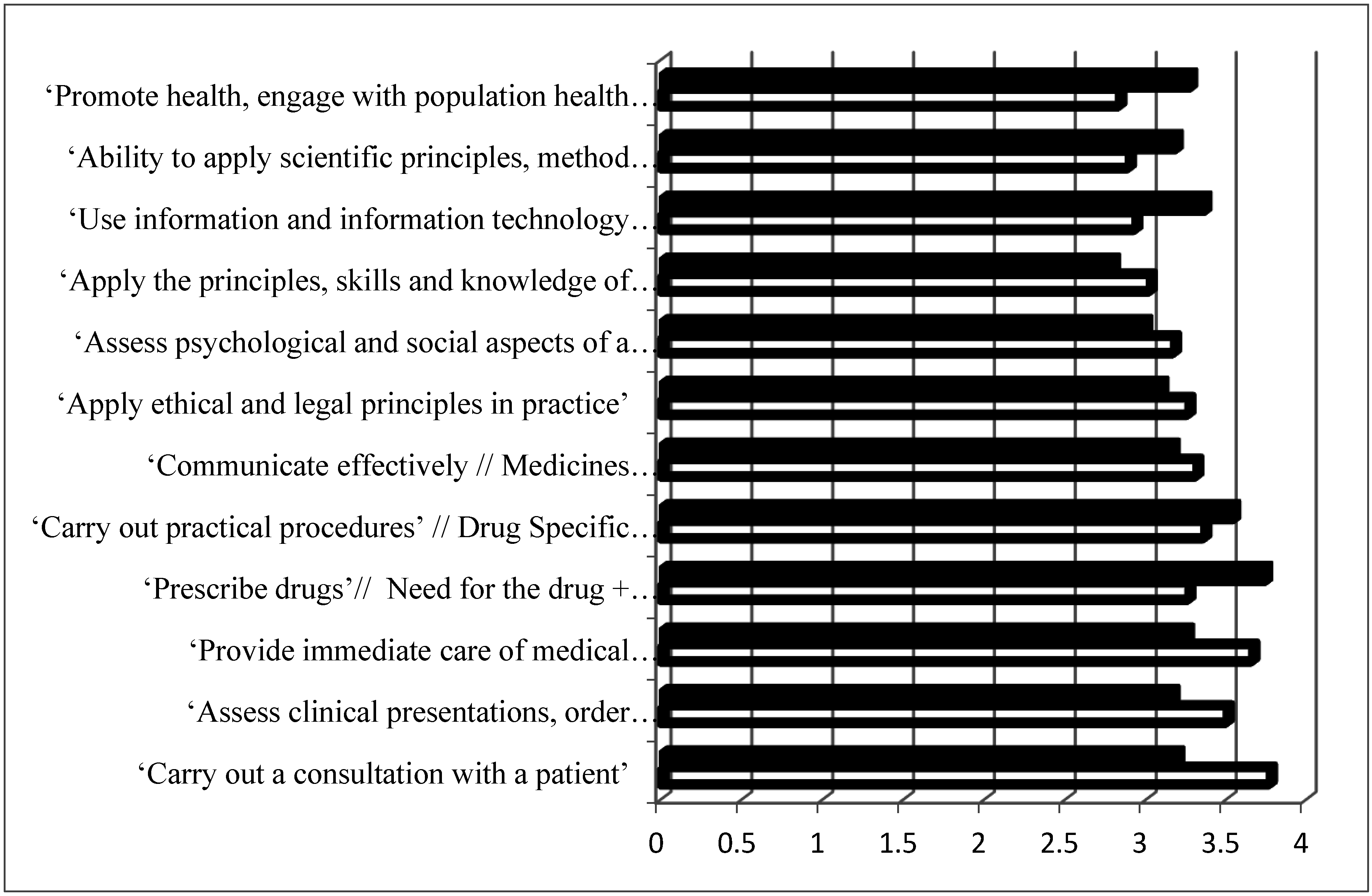

2.3. The Perception by the Practitioners of the Framework Proposals for Pharmacy and Medicine

3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frank, J.R.; Snell, L.S.; Cate, T.O.; Holmboe, E.S.; Carraccio, C.; Swing, S.R.; Harris, P.; Glasgow, N.J.; Campbell, C.; Dath, D.; et al. Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Data on Intra-EU Student Mobility: Strengths and Diversity of European Student Mobility—Agence Erasmus. Available online: https://www.agence-erasmus.fr/docs/2115_soleoscope-10-en.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- Wismar, M.; Maier, C.B.; Glinos, I.A.; Dussault, G.; Figueras, J. (Eds.) Health Professional Mobility and Health Systems: Evidence from 17 European Countries; Observatory Studies Series 23; WHO Regional Office for Europe on Behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011; Available online: http://www.healthpolicyjrnl.com/article/S0168-8510(15)00214-6/fulltext#bibl0005 (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- Directive 2013/55/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 Amending Directive 2005/36/EC on the Recognition of Professional Qualifications and Regulation (EU) No 1024/2012 on Administrative Cooperation through the Internal Market Information System (‘the IMI Regulation’). Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32013L0055 (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- General Level Framework. A Framework for Pharmacists Development in General Pharmacy Practice. Available online: http://www.codeg.org/fileadmin/codeg/pdf/glf/GLF_October_2007_Edition.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- Core Competency Framework for Pharmacists. The Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland. Available online: http://www.thepsi.ie/gns/pharmacy-practice/core-competency-framework.aspx (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- Competencias del Farmacéutico Para Desarrollar Los Servicios Farmacéuticos (SF) Basados en Atención Primaria de Salud (APS) y las Buenas Prácticas en Farmacia (BPF). Available online: http://forofarmaceuticodelasamericas.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Competencias-del-farmacéutico-para-desarrollar-los-SF-basados-en-APS-y-BPF.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- The American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP). White Paper Clinical Pharmacist Competencies: The American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy 2008, 28, 806–815. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, M.S.; Plaza, C.M.; Stowe, C.D.; Robinson, E.T.; DeLander, G.; Beck, D.E.; Melchert, R.B.; Supernaw, R.B.; Roche, V.F.; Gleason, B.L.; et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 Educational Outcomes. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013, 77, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Competency Framework for the Pharmacy Profession. Pharmacy Council of New Zealand, 2009. Available online: http://www.pharmacycouncil.org.nz/cms_show_download.php?id=201 (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- NAPRA. Professional Competencies for Canadian Pharmacists at Entry to Practice. 2007. Available online: http://napra.ca/content_files/files/comp_for_cdn_pharmacists_at_entrytopractice_march2014_b.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- National Competency Standards Framework for Pharmacists in Australia. Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, 2010. Available online: https://www.psa.org.au/downloads/standards/competency-standards-complete.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- PHAR-QA (Quality Assurance in European Pharmacy Education and Training). 2016. Available online: http://www.phar-qa.eu/ (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- The PHARMINE (Pharmacy Education in Europe) Consortium. Work Programme 3: Final Report. Identifying and Defining Competences for Pharmacists. Available online: http://www.pharmine.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PHARMINE-WP3-Final-ReportDEF_LO.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- A Global Competency Framework. FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce, 2012. Available online: https://www.fip.org/files/fip/PharmacyEducation/GbCF_v1.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- Learning Outcomes/Competences for Undergraduate Medical Education in Europe (MEDINE) the Tuning Project (Medicine). Available online: http://tuningacademy.org/medine-medicine/?lang=en (accessed on 13 January 2017).

- Cowpe, J.; Plasschaert, A.; Harzer, W.; Vinkka-Puhakka, H.; Walmsley, A.D. Profile and Competences for the Graduating European Dentist—Update 2009. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 14, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the Recognition of Professional Qualifications. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32005L0036 (accessed on 15 February 2017).

- Miller, G.E. The assessment of clinical skills/competences/performance. Acad. Med. 1990, 65, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; de Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. How do European pharmacy students rank competences for practice? Pharmacy 2016, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; de Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. What is a pharmacist: Opinions of pharmacy department academics and community pharmacists on competences required for pharmacy practice. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Sandulovici, R.; Marcincal, A.; et al. Hospital and Community Pharmacists’ Perceptions of Which Competences Are Important for Their Practice. Pharmacy 2016, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Requirement | Pharmacy | Medicine | Dentistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| The sciences upon which practice is based | X | X | X |

| The scientific methods including the principles of measurement | X | X | X |

| Evaluation of scientific data | X | X | X |

| Structure, function and behavior of healthy and sick persons | X | X | X |

| Traineeship in a community or hospital setting | X | X | X |

| Clinical disciplines and practices | X | X |

| EU Directive 2005 [18] | EU Directive 2013 [4] |

|---|---|

| Preparation of the pharmaceutical form of medicinal products; manufacture and testing of medicinal products; testing of medicinal products in a laboratory for the testing of medicinal products; storage, preservation and distribution of medicinal products at the wholesale stage | Same as 2005 |

| Preparation, testing, storage and supply of medicinal products in pharmacies open to the public | Ordering, manufacture, testing, storage and dispensing of safe, high quality medicinal products in public pharmacies |

| Preparation, testing, storage and dispensing of medicinal products in hospitals | Same as 2005 |

| Provision of information and advice on medicinal products | Medication management and provision of information and advice about medicinal products and general health information |

| Provision of advice and support to patients in connection with the use of non-prescription medicines and self-medication | |

| Contributions to public health and information campaigns |

| Domain | Major Competences | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PHAR-QA | MEDINE | ADEE | |

| 1. Professionalism | Personal competences: values. | Professional attributes | Professional attitude and behavior |

| Personal competences: learning and knowledge. | Professional working | ||

| Personal competences: values. | Apply ethical and legal principles | Ethics and jurisprudence | |

| 2. Interpersonal, communication and social skills | Personal competences: communication and organizational skills. | Communicate effectively in a medical context | Communication |

| 3. Knowledge base, information and information literacy | Personal competences: learning and knowledge. | Apply the principles, skills and knowledge of evidence-based medicine | Application of basic biological, medical, technical and clinical sciences |

| Personal competences: learning and knowledge. | Use information and information technology effectively in a medical context | Acquiring and using information | |

| 4. Clinical information gathering | Patient care competences: patient consultation and assessment. | Carry out a consultation with a patient | Obtaining and recording a complete history of the patient’s medical, oral and dental state |

| Assess psychological and social aspects of a patient’s illness’ | |||

| 5. Diagnosis and Treatment planning | Patient care competences: need for drug treatment. | Assess clinical presentations, order investigations, make differential diagnoses and negotiate a management plan | Decision-making, clinical reasoning and judgment |

| Patient care competences: drug interactions. | Provide immediate care of medical emergencies, including First Aid and resuscitation’ | ||

| Patient care competences: drug dose and formulation. | |||

| Patient care competences: provision of information and service. | |||

| 6. Therapy, establishing and maintaining health | Patient care competences: monitoring of drug therapy. | Carry out practical procedures | Establishing and maintaining oral health |

| Prescribe drugs | |||

| 7. Prevention and health promotion | Patient care competences: patient education. | Promote health, engage with population health issues and work effectively in a health care system | Improving oral health of individuals, families and groups in the community |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Pozo, A. A Comparison of Competences for Healthcare Professions in Europe. Pharmacy 2017, 5, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy5010008

Sánchez-Pozo A. A Comparison of Competences for Healthcare Professions in Europe. Pharmacy. 2017; 5(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy5010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Pozo, Antonio. 2017. "A Comparison of Competences for Healthcare Professions in Europe" Pharmacy 5, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy5010008