A Study of Financial Literacy of Investors—A Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

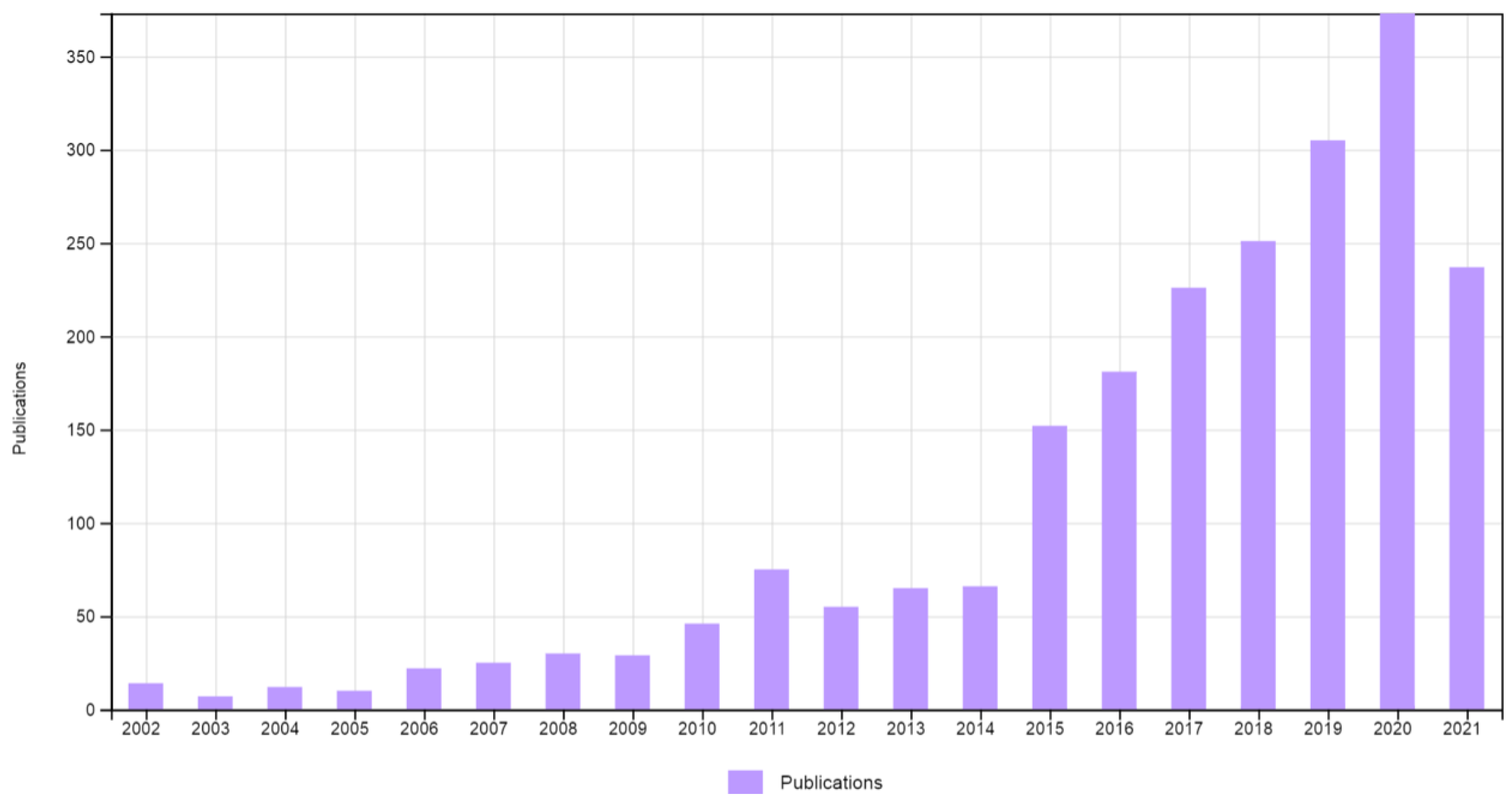

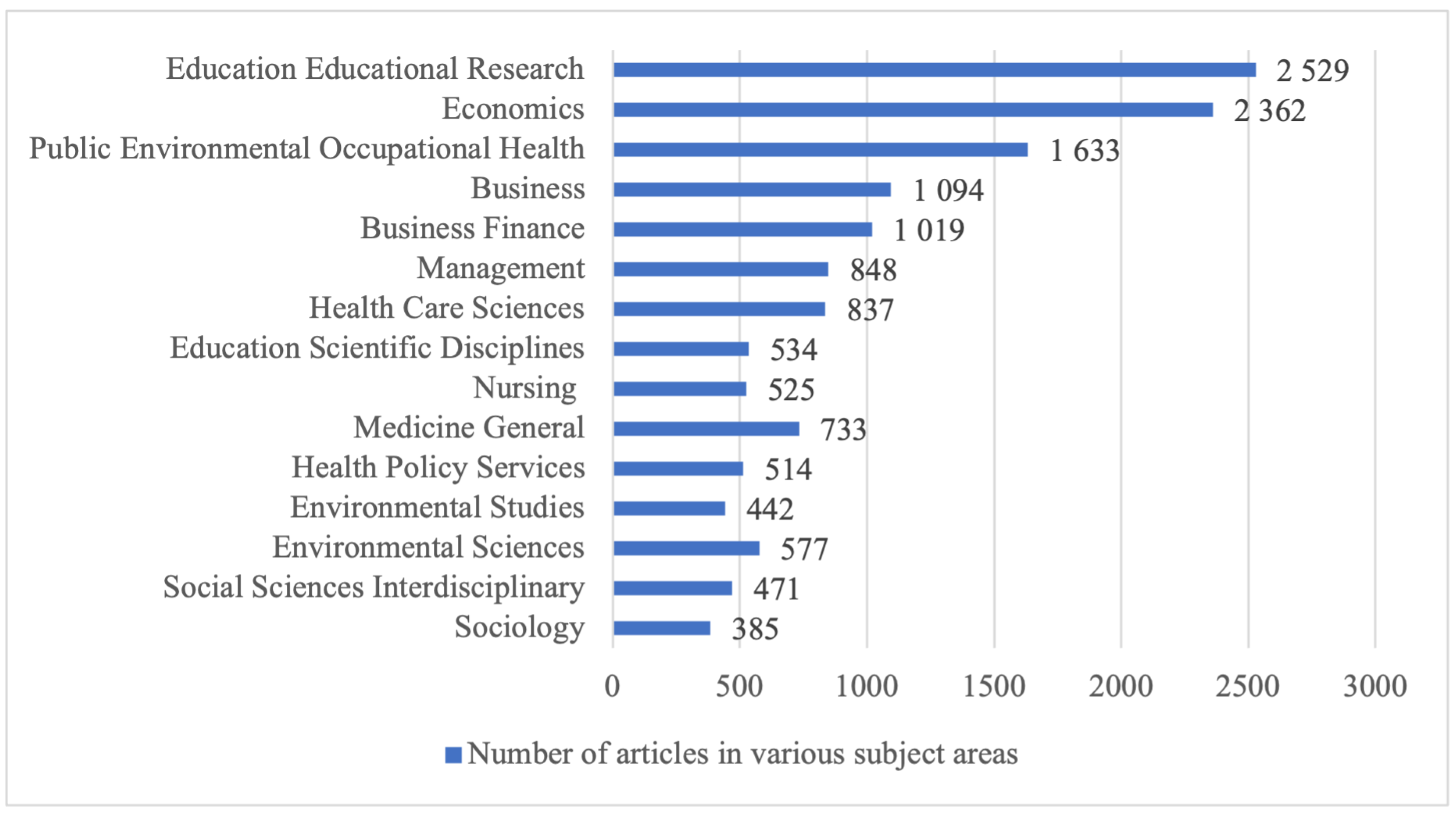

3.1. General Descriptive Statistics

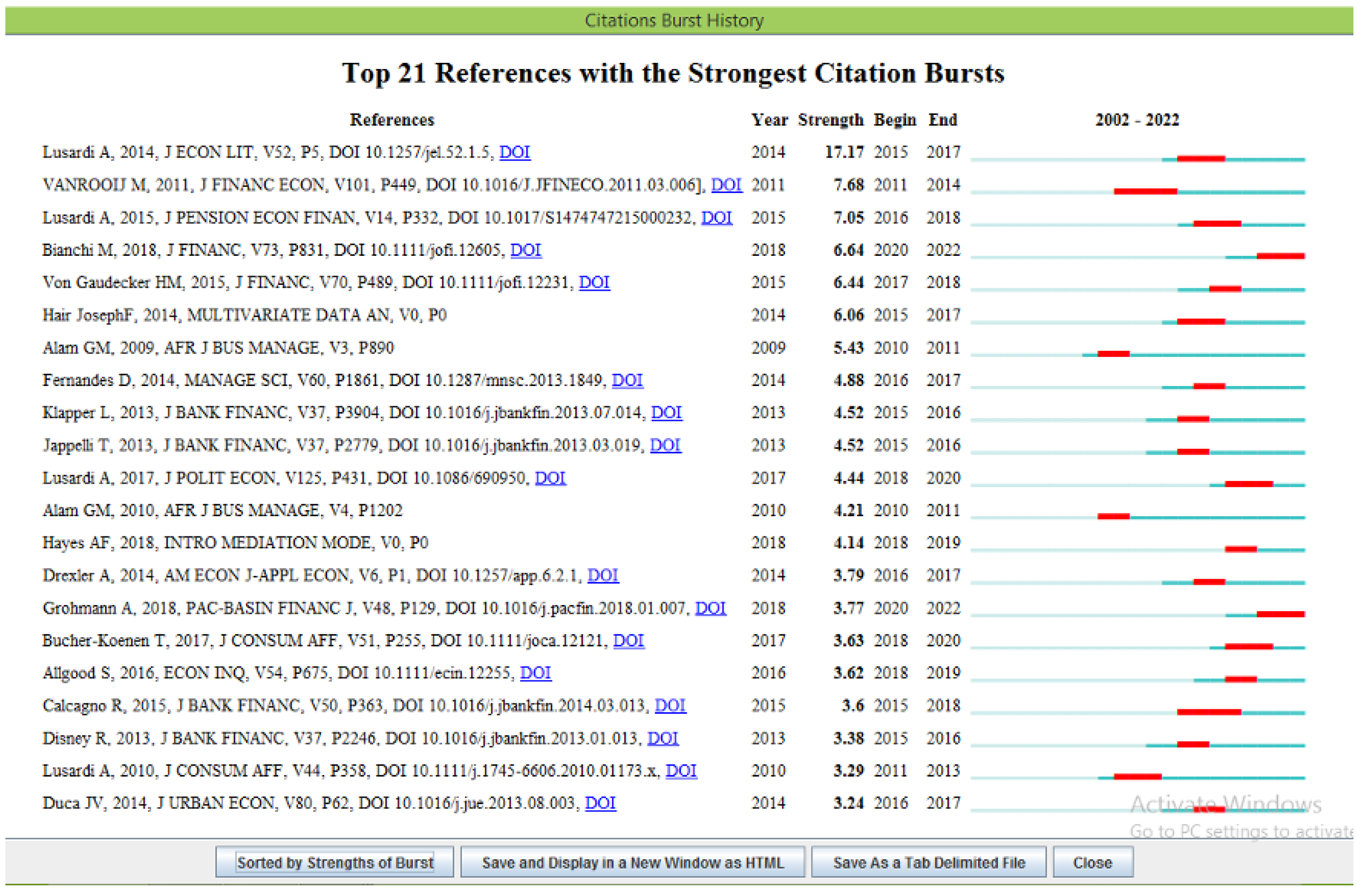

3.2. Citation Network Analysis

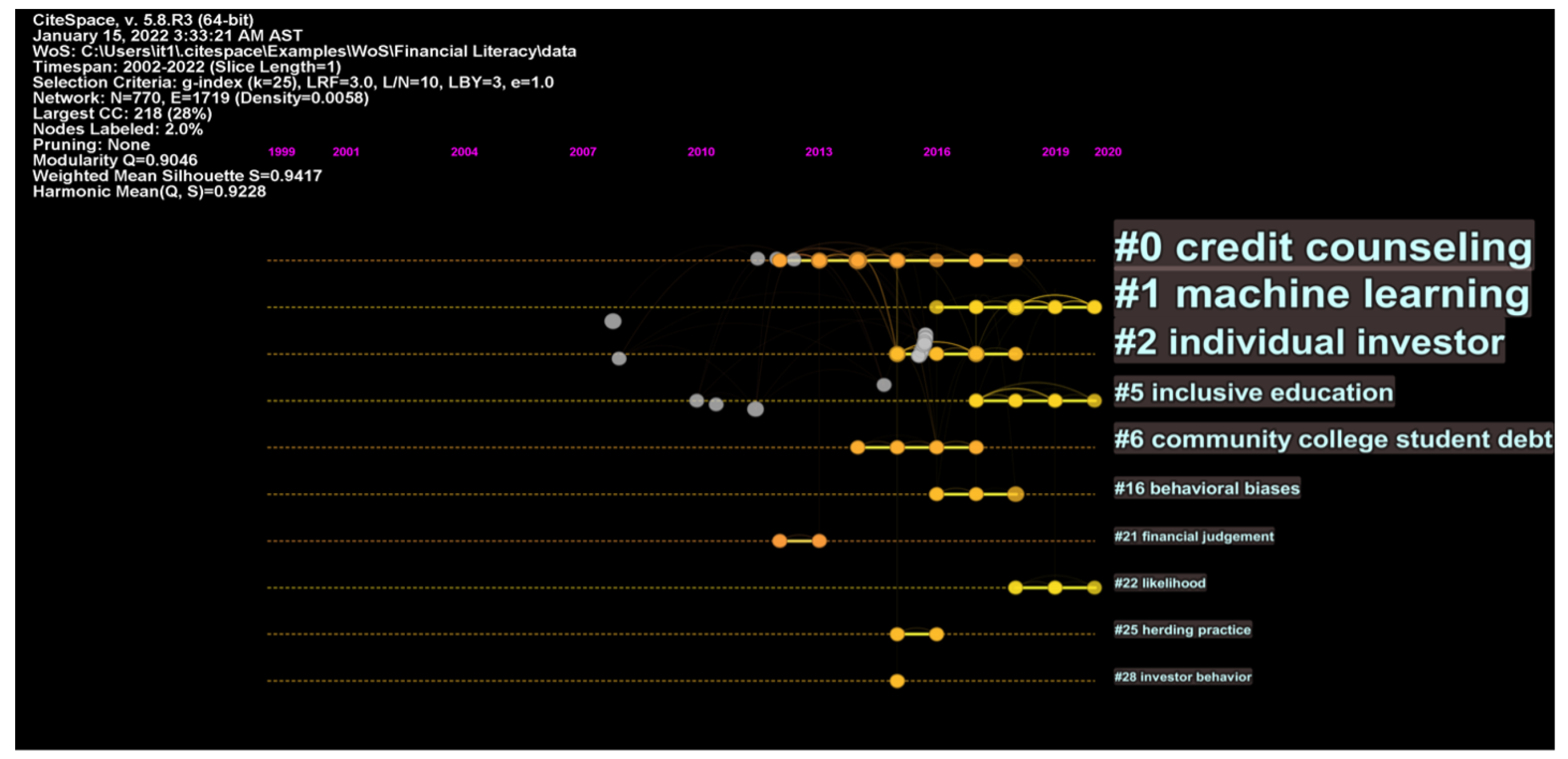

3.3. Co-Citation Analysis

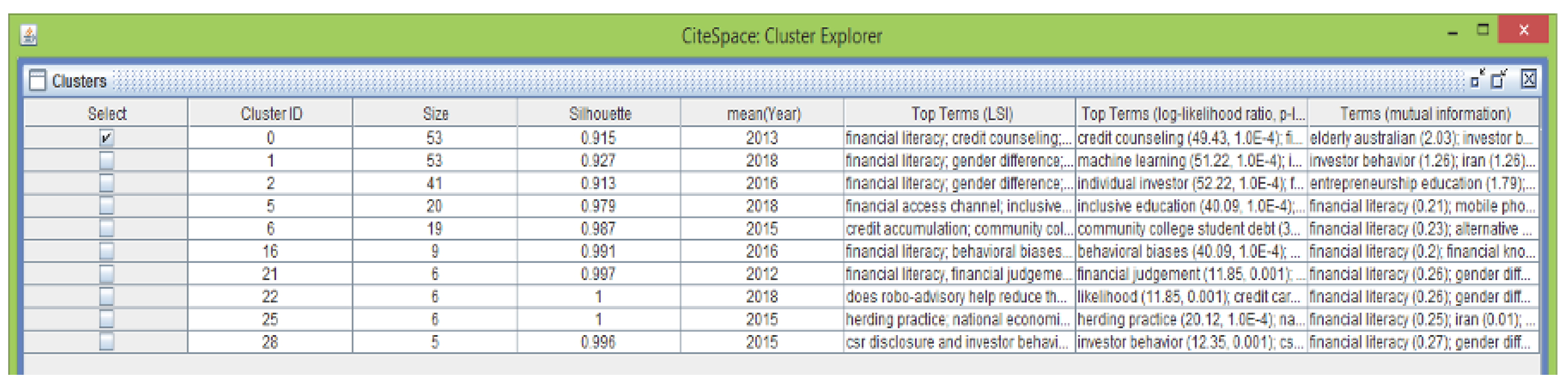

3.3.1. Clustering

3.3.2. Content Analysis

Cluster #0: Credit Counseling

Cluster #1: Machine Learning

Cluster #2: Individual Investor

Cluster #5: Inclusive Education

Cluster #6: Community College Student Debt

Cluster #16: Behavioral Biases

Cluster #21: Financial Judgment

Cluster #28: Investor Behavior

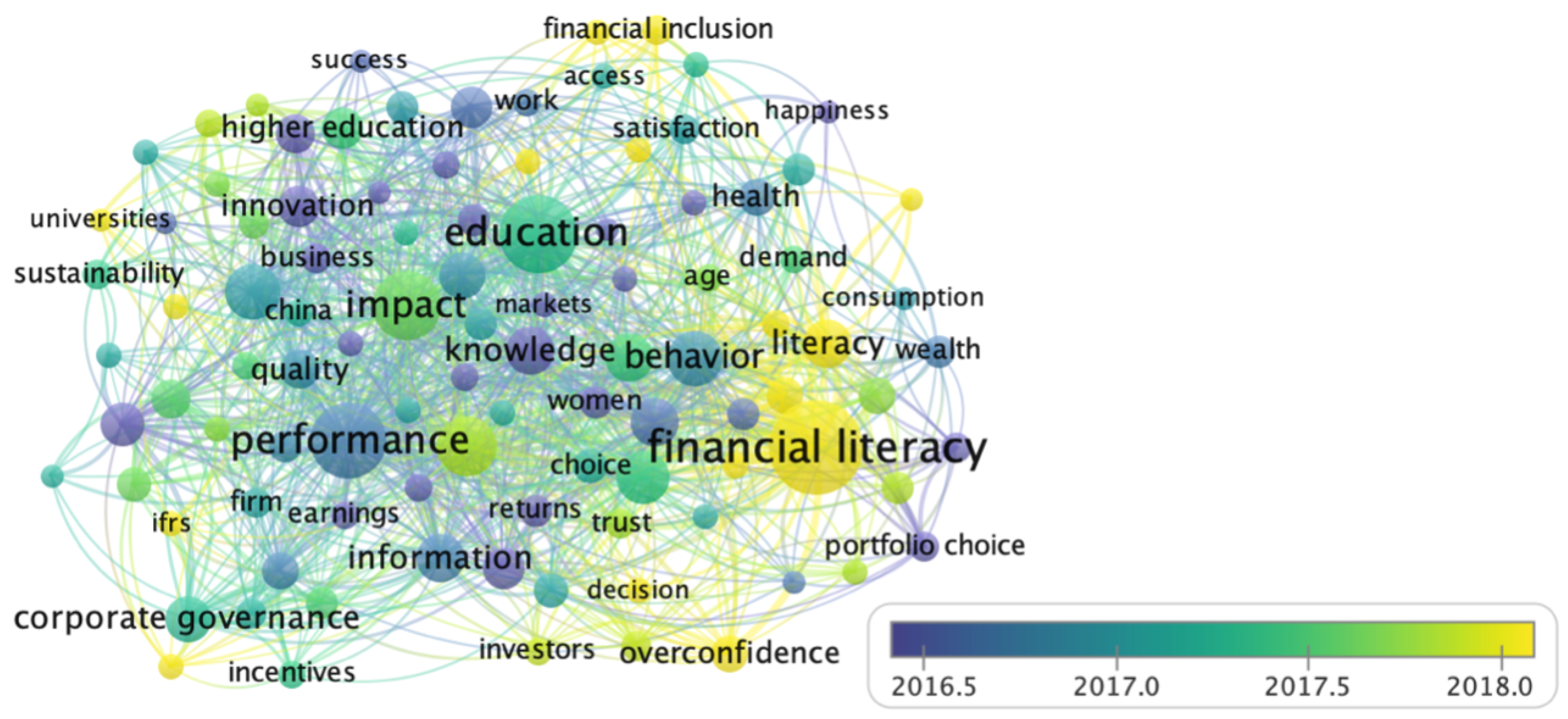

3.4. Topmost Active Areas, Recent Research Trends, and Emerging Themes

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research

- The study was based on a review of 2182 publications published in the last two decades on financial literacy in the financial sector. The study adopted a combination of keywords, and various keyword combinations may have shown different results.

- To better understand the topic, future studies should include all ten clusters. Because of these findings, this field requires more in-depth research.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TC | Total Citations |

| TP | Total Publications |

References

- Ahmed, Shamima, Muneer M. Alshater, Anis El Ammari, and Helmi Hammami. 2022. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in finance: A bibliometric review. Research in International Business and Finance 61: 101646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Gazi Mahabubul. 2009. Can governance and regulatory control ensure private higher education as business or public goods in bangladesh? African Journal of Business Management 3: 890–906. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, Gazi Mahabubul, and Kazi Enamul Hoque. 2010. Who gains from brain and body drain business-developing/developed world or individuals: A comparative study between skilled and semi/unskilled emigrants. African Journal of Business Management 4: 534–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Mohammad Mahbubi, Abrista Devi, Hafas Furqani, and Hamzah Hamzah. 2020. Islamic financial inclusion determinants in indonesia: An anp approach. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 13: 727–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgood, Sam, and William B. Walstad. 2016. The effects of perceived and actual financial literacy on financial behaviors. Economic Inquiry 54: 675–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshater, Muneer M., Osama F. Atayah, and Allam Hamdan. 2021. Journal of sustainable finance and investment: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 2021: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Alshater, Muneer M., M. Kabir Hassan, Mamunur Rashid, and Rashedul Hasan. 2021. A bibliometric review of the waqf literature. Eurasian Economic Review 2021: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshater, Muneer M., Ram Al Jaffri Saad, Norazlina Abd Wahab, and Irum Saba. 2021. What do we know about zakat literature? a bibliometric review. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 12: 544–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, Simplice A., and John Kuada. 2020. Building knowledge economies in africa: An introduction. Contemporary Social Science 15: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Adele, and Flore-Anne Messy. 2012. Measuring Financial Literacy: Results of the OECD/International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study (OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 15). Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H. Kent, Satish Kumar, Nisha Goyal, and Vidhu Gaur. 2019. How financial literacy and demographic variables relate to behavioral biases. Managerial Finance 45: 124–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, James, and Zoë Oldfield. 2007. Understanding pensions: Cognitive function, numerical ability and retirement saving. Fiscal Studies 28: 143–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bianchi, Milo. 2018. Financial literacy and portfolio dynamics. The Journal of Finance 73: 831–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanco-Mesa, Fabio, José M. Merigó, and Anna M. Gil-Lafuente. 2017. Fuzzy decision-making: A bibliometric-based review. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 32: 2033–50. [Google Scholar]

- Boatman, Angela, and Brent J. Evans. 2017. How financial literacy, federal aid knowledge, and credit market experience predict loan aversion for education. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 671: 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boutsouki, Christina. 2019. Impulse behavior in economic crisis: A data driven market segmentation. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 47: 974–96. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, Lukas, and Tobias Meyll. 2020. Robo-advisors: A substitute for human financial advice? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 25: 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Meta, John Grigsby, Wilbert van der Klaauw, Jaya Wen, and Basit Zafar. 2016. Financial education and the debt behavior of the young. The Review of Financial Studies 29: 2490–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bucher-Koenen, Tabea, and Annamaria Lusardi. 2011. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 10: 565–84. [Google Scholar]

- Calcagno, Riccardo, and Chiara Monticone. 2015. Financial literacy and the demand for financial advice). Journal of Banking & Finance 50: 363–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Bruce, and Lorraine Dearden. 2017. Conceptual and empirical issues for alternative student loan designs: The significance of loan repayment burdens for the united states. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 671: 249–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chaomei. 2014. The citespace manual. College of Computing and Informatics 1: 1–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Chaomei, Fidelia Ibekwe-SanJuan, and Jianhua Hou. 2010. The structure and dynamics of cocitation clusters: A multiple-perspective cocitation analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61: 1386–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christiansen, Charlotte, Juanna Schröter Joensen, and Jesper Rangvid. 2008. Are economists more likely to hold stocks? Review of Finance 12: 465–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, Robert, Annamaria Lusardi, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2014. Financial knowledge and 401 (k) investment performance: A case study. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 16: 324–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb-Clark, Deborah A., Sonja C. Kassenboehmer, and Mathias G. Sinning. 2016. Locus of control and savings. Journal of Banking & Finance 73: 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Shawn, Anna Paulson, and Gauri Kartini Shastry. 2014. Smart money? the effect of education on financial outcomes. The Review of Financial Studies 27: 2022–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comerio, Niccolò, and Fernanda Strozzi. 2019. Tourism and its economic impact: A literature review using bibliometric tools. Tourism Economics 25: 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culnan, Mary J. 1987. Mapping the intellectual structure of mis, 1980–1985: A co-citation analysis. MIS Quarterly 11: 341–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disney, Richard, and John Gathergood. 2013. Financial literacy and consumer credit portfolios. Journal of Banking & Finance 37: 2246–54. [Google Scholar]

- Drexler, Alejandro, Greg Fischer, and Antoinette Schoar. 2014. Keeping it simple: Financial literacy and rules of thumb. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duca, John V., and Anil Kumar. 2014. Financial literacy and mortgage equity withdrawals. Journal of Urban Economics 80: 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, Xiangnan, Bin Lu, Xinyuan Song, and Shuang Ma. 2019. Financial literacy and household finances: A bayesian two-part latent variable modeling approach. Journal of Empirical Finance 51: 119–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Daniel, John G. Lynch, and Richard G. Netemeyer. 2014. Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Management Science 60: 1861–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, Fernando, Kristen M. Glasener, Meghan Oster, Brian P. McCall, and Stephen L. DesJardins. 2017. Navigating the financial aid process: Borrowing outcomes among first-generation and non-first-generation students. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 671: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gödker, Katrin, and Lasse Mertins. 2018. Csr disclosure and investor behavior: A proposed framework and research agenda. Behavioral Research in Accounting 30: 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodell, John W., Satish Kumar, Weng Marc Lim, and Debidutta Pattnaik. 2021. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in finance: Identifying foundations, themes, and research clusters from bibliometric analysis. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 32: 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, Antonia. 2018. Financial literacy and financial behavior: Evidence from the emerging asian middle class. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 48: 129–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, Rolph E. Anderson, and Ronald L. Tatham. 2014. Pearson new international edition. In Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. Essex: Pearson Education Limited Harlow. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M. Kabir, Muneer M. Alshater, Rashedul Hasan, and Abul Bashar Bhuiyan. 2021. Islamic microfinance: A bibliometric review. Global Finance Journal 49: 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs 85: 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Yu-Jen, and Wei-Che Tsai. 2018. Financial literacy and participation in the derivatives markets. Journal of Banking & Finance 88: 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Huston, Sandra J. 2010. Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs 44: 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Danling, and Sonya S. Lim. 2018. Trust and household debt. Review of Finance 22: 783–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Tim, and Lukas Menkhoff. 2017. Does financial education impact financial literacy and financial behavior, and if so, when? The World Bank Economic Review 31: 611–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempson, Elaine, Sharon Collard, and Nick Moore. 2006. Measuring financial capability: An exploratory study for the financial services authority. Consumer Financial Capability: Empowering European Consumers 2006: 39. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Ashraf, John W. Goodell, M. Kabir Hassan, and Andrea Paltrinieri. 2021. A bibliometric review of finance bibliometric papers. Finance Research Letters 2021: 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, Leora, Annamaria Lusardi, and Georgios A. Panos. 2013. Financial literacy and its consequences: Evidence from russia during the financial crisis. Journal of Banking & Finance 37: 3904–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski, ukasz. 2021. Household’s overindebtedness during the COVID-19 crisis: The role of debt and financial literacy. Risks 9: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jianjun, Qize Li, and Xu Wei. 2020. Financial literacy, household portfolio choice and investment return. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 62: 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Kai, Jason Rollins, and Erjia Yan. 2018. Web of science use in published research and review papers 1997–2017: A selective, dynamic, cross-domain, content-based analysis. Scientometrics 115: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, Thien Sang, Rasid Mail, Mohd Rahimie Abd Karim, Zatul Karamah Ahmad Baharul Ulum, Junainah Jaidi, and Raman Noordin. 2018. A serial mediation model of financial knowledge on the intention to invest: The central role of risk perception and attitude. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 20: 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Xi, Aaron Bruhn, and Jananie William. 2019. Extending financial literacy to insurance literacy: A survey approach. Accounting & Finance 59: 685–713. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Weishu. 2019. The data source of this study is Web of Science Core Collection? Not enough. Scientometrics 121: 1815–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Zhigao, Yimei Yin, Weidong Liu, and Michael Dunford. 2015. Visualizing the intellectual structure and evolution of innovation systems research: A bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 103: 135–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, Olivia S. Mitchell, and Vilsa Curto. 2010. Financial literacy among the young. Journal of Consumer Affairs 44: 358–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2011. Financial literacy and retirement planning in the United States. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 10: 509–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2014. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 52: 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, and Peter Tufano. 2015. Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 14: 332–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, Pierre-Carl Michaud, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2017. Optimal financial knowledge and wealth inequality. Journal of Political Economy 125: 431–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madureira, Bruno, Tiago Pinto, Filipe Fernandes, and Zita Vale. 2017. Context analysis in energy resource management residential buildings. Paper presented at 2017 IEEE Manchester PowerTech, Manchester, UK, June 18–22; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Metawa, Noura, M. Kabir Hassan, Saad Metawa, and M. Faisal Safa. 2019. Impact of behavioral factors on investors’ financial decisions: Case of the egyptian stock market. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 12: 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Olivia S., and Annamaria Lusardi. 2011. Financial literacy around the world: An overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10: 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- Oehler, Andreas, Matthias Horn, and Florian Wedlich. 2018. Young adults’ subjective and objective risk attitude in financial decision-making: Evidence from the lab and the field. Review of Behavioral Finance 10: 274–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parise, Gianpaolo, and Kim Peijnenburg. 2019. Non-cognitive abilities and financial distress: Evidence from a representative household panel. The Review of Financial Studies 32: 3884–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Ritesh, John W. Goodell, Marco Ercole Oriani, Andrea Paltrinieri, and Larisa Yarovaya. 2022. A bibliometric review of financial market integration literature. International Review of Financial Analysis 80: 102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Mia Hang. 2020. In law we trust: Lawyer ceos and stock liquidity. Journal of Financial Markets 50: 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Mahfuzur, Nurul Azma, Md Masud, Abdul Kaium, and Yusof Ismail. 2020. Determinants of indebtedness: Influence of behavioral and demographic factors. International Journal of Financial Studies 8: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivière-Giordano, Géraldine, Sophie Giordano-Spring, and Charles H. Cho. 2018. Does the level of assurance statement on environmental disclosure affect investor assessment? an experimental study. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 9: 336–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, Razan. 2019. Examining the investment behavior of arab women in the stock market. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 22: 151–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevcík, Karel. 2015. Pisa 2012 results: Students and money: Financial literacy skills for the 21st century (volume vi). Pedagogická Orientace 25: 632. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Chung-Hua, Shih-Jie Lin, De-Piao Tang, and Yu-Jen Hsiao. 2016. The relationship between financial disputes and financial literacy. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 36: 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, Henry. 1973. Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 24: 265–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolper, Oscar. 2018. It takes two to tango: Households’ response to financial advice and the role of financial literacy. Journal of Banking & Finance 92: 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Supanantaroek, Suthinee, Robert Lensink, and Nina Hansen. 2017. The impact of social and financial education on savings attitudes and behavior among primary school children in Uganda. Evaluation Review 41: 511–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchamyou, Vanessa Simen. 2020. Education, lifelong learning, inequality and financial access: Evidence from African countries. Contemporary Social Science 15: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tullio, Jappelli, and Padula Mario. 2013. Investment in financial literacy and saving decisions. Journal of Banking & Finance 37: 2779–92. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, Nees, and Ludo Waltman. 2010. Software survey: Vosviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84: 523–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Rooij, Maarten, Annamaria Lusardi, and Rob Alessie. 2011. Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics 101: 449–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Von Gaudecker, Hans-Martin. 2015. How does household portfolio diversification vary with financial literacy and financial advice? The Journal of Finance 70: 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Yen-Chun Jim, and Tienhua Wu. 2017. A decade of entrepreneurship education in the Asia Pacific for future directions in theory and practice. Management Decision 55: 1333–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Shuo, Junwan Liu, Dongsheng Zhai, Xin An, Zheng Wang, and Hongshen Pang. 2018. Overlapping thematic structures extraction with mixed-membership stochastic blockmodel. Scientometrics 117: 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Top Authors | Top Institutions | Top Countries | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | TP | TC | Institution | TP | TC | Country | TP | TC |

| Annamaria Lusardi | 14 | 1833 | University of Pennsylvania | 25 | 1493 | USA | 586 | 14,865 |

| Olivia S. Mitchell | 11 | 870 | George Washington University | 18 | 1478 | England | 193 | 3217 |

| Paul Gerrans | 7 | 59 | Tilburg University | 17 | 504 | Australia | 171 | 1763 |

| Satish Kumar | 7 | 44 | National Bureau of Economic Research | 16 | 808 | Peoples R China | 140 | 1747 |

| Kelmara Mendes Vieira | 5 | 69 | Erasmus University | 15 | 660 | Germany | 103 | 1623 |

| Tobias Meyll | 5 | 46 | World Bank | 13 | 651 | Malaysia | 95 | 423 |

| ACG Potrich | 4 | 69 | Tsinghua University | 12 | 253 | Italy | 88 | 1462 |

| Roy Kouwenberg | 4 | 80 | University Western Australia | 12 | 202 | India | 85 | 407 |

| Mario Padula | 4 | 191 | Harvard University | 11 | 1221 | Canada | 77 | 1278 |

| Andreas Walter | 4 | 29 | University of Oxford | 11 | 292 | Netherlands | 58 | 2158 |

| Jing Jian Xiao | 4 | 204 | Centre for Economic Policy Research | 10 | 77 | France | 50 | 643 |

| Alex Yue Feng Zhu | 4 | 10 | University of California | 9 | 289 | Taiwan | 45 | 513 |

| Elsa Fornero | 4 | 129 | University of Groningen | 8 | 603 | Sweden | 37 | 640 |

| Susan Thorp | 4 | 24 | University of Rhode Island | 5 | 206 | Portugal | 34 | 917 |

| CAB Van der Cruijsen | 4 | 44 | University of Colorado | 5 | 521 | Scotland | 34 | 439 |

| Journal | Publisher | TP | TC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Pension Economics and Finance | Cambridge University Press | 45 | 1863 |

| Social Indicators Research | Springer International Publishing | 44 | 614 |

| Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance | Elsevier | 40 | 250 |

| Journal of Banking and Finance | Elsevier | 37 | 1385 |

| Journal of Risk and Financial Management | MDPI | 24 | 75 |

| Pacific-Basin Finance Journal | Elsevier | 21 | 149 |

| Journal of Behavioral Finance | Taylor and Francis Ltd. | 20 | 200 |

| Accounting and Finance | Wiley-Blackwell | 19 | 157 |

| Review of Financial Studies | Oxford University Press | 16 | 609 |

| Journal of Financial Economics | Elsevier | 15 | 1088 |

| European Journal of Finance | Routledge | 15 | 53 |

| Review of Finance | Oxford University Press | 12 | 215 |

| Management Science | Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences | 12 | 1158 |

| Journal of Finance | Wiley-Blackwell | 9 | 495 |

| World Bank Economic Review | Oxford University Press | 9 | 365 |

| Reference | Article Title | Journal | Times Cited, (WoS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fernandes et al. (2014) | Financial Literacy, Financial Education, and Downstream Financial Behaviors | Management Science | 487 |

| Van Rooij et al. (2011) | Financial Literacy and Stock Market Participation | Journal of Financial Economics | 437 |

| Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) | Financial Literacy Around the World: An Overview | Journal of Pension Economics and Finance | 421 |

| Mitchell and Lusardi (2011) | Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in the United States | Journal of Pension Economics and Finance | 227 |

| Lusardi and Tufano (2015) | Debt Literacy, Financial Experiences, and Over-indebtedness | Journal of Pension Economics and Finance | 214 |

| Tullio and Mario (2013) | Investment in Financial Literacy and Savings Decisions | Journal of Banking and Finance | 161 |

| Cole et al. (2014) | Smart Money? The Effect of Education on Financial Outcome | Review of Financial Studies | 158 |

| Von Gaudecker (2015) | How does Household Portfolio diversification vary with Financial Literacy and Financial Advice? | Journal of Finance | 132 |

| Banks and Oldfield (2007) | Understanding Pensions: Cognitive Function, Numerical Ability, and Retirement Saving | Fiscal Studies | 124 |

| Klapper et al. (2013) | Financial Literacy and Its Consequences: Evidence from Russia during the Financial Crisis | Journal of Banking and Finance | 109 |

| Calcagno and Monticone (2015) | Financial Literacy and the Demand for Financial Advice | Journal of Banking and Finance | 109 |

| Christiansen and Rangvid (2008) | Are Economists more Likely to Hold Stocks? | Review of Finance | 78 |

| Brown et al. (2016) | Financial Education and the Debt Behavior of the Young | Review of Financial Studies | 67 |

| Kaiser and Menkhoff (2017) | Does Financial Education Impact Financial Literacy and Financial Behavior and If Thus, When? | World Bank Economic Review | 56 |

| Cobb-Clark et al. (2016) | Locus of Control and Savings | Journal of Banking and Finance | 54 |

| S. No. | Reference | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Feng et al. (2019) | Investigate the impacts of financial literacy on both sides of the household balance sheet, namely, household debt and assets, using a national sample from the China Household Finance Survey. |

| 2. | Lin et al. (2019) | Investigate factors that may influence individuals’ insurance decision-making. |

| 3. | Stolper (2018) | Homophily has a strong positive impact on the chance of adopting financial advice. |

| 4. | Baker et al. (2019) | Examine how financial literacy and demographic variables are related to behavioral biases. |

| 5. | Boutsouki (2019) | Apply cluster analysis to identify homogeneous subgroups among impulse buyers based on their demographic characteristics and their preference for atmospheric elements. |

| 6. | Metawa et al. (2019) | Investigate the relationship between investors demographic characteristics and their investment decisions through behavioral factors as mediator variables in the Egyptian stock market. |

| 7. | Salem (2019) | Investigate the investment behavior of Arab women on risk tolerance, investment confidence, investment literacy levels, and herding behavior. |

| 8. | Parise and Peijnenburg (2019) | Provides evidence of how non-cognitive abilities affect financial distress. |

| 9. | Li et al. (2020) | Investigates the impact of financial literacy on Chinese households’ portfolio decisions and financial market investment performance. |

| 10. | Rahman et al. (2020) | Design a particular determinants model to investigate the impact of behavioral and demographic variables on indebtedness. |

| 11. | Pham (2020) | Highlights the importance of CEO characteristics in enhancing financial market quality. |

| 12. | Brenner and Meyll (2020) | Investigate whether automated financial advisers (Robo-advisors) reduce demand for human financial advice from financial service providers. |

| 13. | Ali et al. (2020) | Uncover the determinants of Islamic financial inclusion in Indonesia. |

| 14. | Tchamyou (2020) | The impact of financial access on modulating the effect of education and lifelong learning on inequality is examined in 48 African countries from 1996 to 2014. |

| 15. | Asongu and Kuada (2020) | Provides a context for understanding the importance of building knowledge economies in Africa and summarises the main contributions to the themed issue. |

| 16. | Kurowski (2021) | Examine if households with greater financial and debt literacy have better budget management skills, reducing the risk of individuals failing to repay their loans in the crisis. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ansari, Y.; Albarrak, M.S.; Sherfudeen, N.; Aman, A. A Study of Financial Literacy of Investors—A Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2022, 10, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs10020036

Ansari Y, Albarrak MS, Sherfudeen N, Aman A. A Study of Financial Literacy of Investors—A Bibliometric Analysis. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2022; 10(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs10020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnsari, Yasmeen, Mansour Saleh Albarrak, Noorjahan Sherfudeen, and Arfia Aman. 2022. "A Study of Financial Literacy of Investors—A Bibliometric Analysis" International Journal of Financial Studies 10, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs10020036