Impact of the Gastro-Intestinal Bacterial Microbiome on Helicobacter-Associated Diseases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Burden of Helicobacter-Associated Infectious Diseases

1.2. The Association between Helicobacter-Associated Disease and the Bacterial Microbiome: A Lot to Learn

2. Impact of the Microbiome on Intestinal Diseases

2.1. How to Analyze Bacterial Intestinal Microbiota

2.2. Gut Microbiota Structure and Evolution

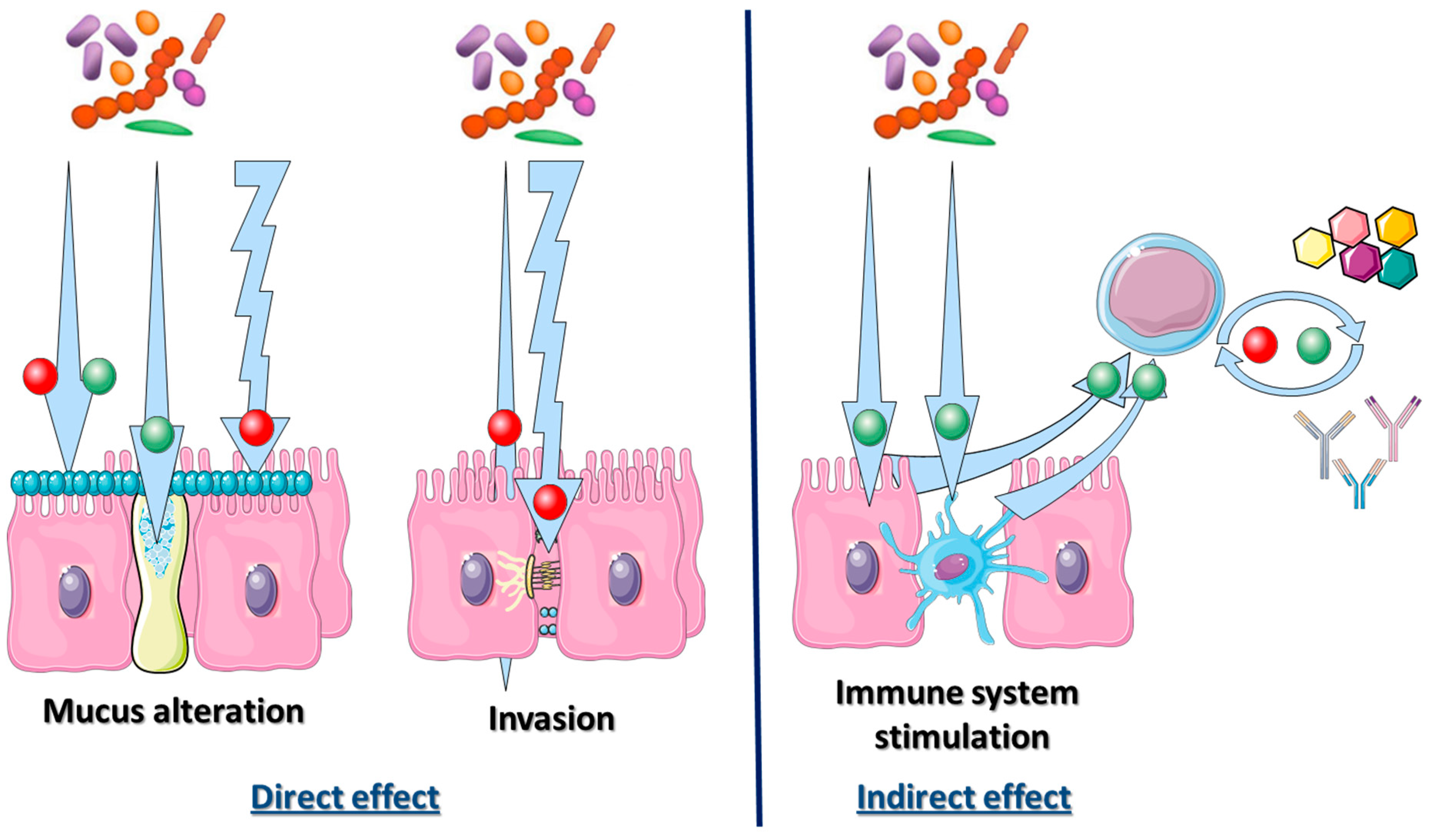

2.3. Bacterial Microbiota Direct Interaction with the Intestinal Tract Environment: The Mucosal Interface

2.4. Bacterial Microbiota Interaction with Innate and Adaptive Immune Systems

2.5. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori and the Gastric Microbiome

3. Clinical Use of the Gastro-Intestinal Microbiome Impact during Helicobacter-Associated Diseases: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives

3.1. Could Stool Microbiome be Used to Detect Gastric Infection by Helicobacter pylori?

3.2. Could Characterization of the Stool Microbiome Be Used as a Prognostic Biomarker to Detect Helicobacter-Associated Complications?

3.3. Could Stool Microbiome Characterization be Used to Predict Therapeutic Effect of Anticancer Chemotherapies?

3.4. Could Stool Microbiome Characterization Be Used to Modify Response to Therapies?

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atherton, J.C.; Blaser, M.J. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: Ancient history, modern implications. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 2475–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burucoa, C.; Axon, A. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2017, 22 (Suppl. 1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.; Thiberge, J.-M.; Kalach, N.; Bergeret, M.; Dupont, C.; Labigne, A.; Dauga, C. Using macro-arrays to study routes of infection of Helicobacter pylori in three families. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgouras, D.N.; Trang, T.T.H.; Yamaoka, Y. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2015, 20 (Suppl. 1), 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.R.; Winter, J.A.; Robinson, K. Differential inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori infection: Etiology and clinical outcomes. J. Inflamm. Res. 2015, 8, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Correa, P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988, 48, 3554–3560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Correa, P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: A multistep and multifactorial process—First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 6735–6740. [Google Scholar]

- Ražuka-Ebela, D.; Giupponi, B.; Franceschi, F. Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases. Helicobacter 2018, 23 (Suppl. 1), e12520. [Google Scholar]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Megraud, F.; O’Morain, C.A.; Gisbert, J.P.; Kuipers, E.J.; Axon, A.T.; Bazzoli, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Atherton, J.; Graham, D.Y.; et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut 2017, 66, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Contreras, A.; Goldfarb, K.C.; Godoy-Vitorino, F.; Karaoz, U.; Contreras, M.; Blaser, M.J.; Brodie, E.L.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G. Structure of the human gastric bacterial community in relation to Helicobacter pylori status. ISME J. 2011, 5, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.; Rasmussen, L. Helicobacter pylori-coccoid forms and biofilm formation. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2009, 56, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederberg, J. ‘Ome Sweet’ Omics—A Genealogical Treasury of Words. Scientist 2001, 15, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa, A.; Xie, C.; Kirkness, E.; Biggs, W.; Wong, E.; Turpaz, Y.; Bloom, K.; Delwart, E.; Nelson, K.E.; Venter, J.C.; et al. The blood DNA virome in 8000 humans. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006292. [Google Scholar]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLOS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garud, N.R.; Good, B.H.; Hallatschek, O.; Pollard, K.S. Evolutionary dynamics of bacteria in the gut microbiome within and across hosts. PLOS Pathog. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erb-Downward, J.R.; Thompson, D.L.; Han, M.K.; Freeman, C.M.; McCloskey, L.; Schmidt, L.A.; Young, V.B.; Toews, G.B.; Curtis, J.L.; Sundaram, B.; et al. Analysis of the lung microbiome in the “healthy” smoker and in COPD. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huse, S.M.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Fodor, A.A. A core human microbiome as viewed through 16S rRNA sequence clusters. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paepe, M.; Leclerc, M.; Tinsley, C.R.; Petit, M.-A. Bacteriophages: An underestimated role in human and animal health? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberstein, B.; Quintanilha, A.G.; Santos, M.A.A.; Pajecki, D.; Moura, E.G.; Alves, P.R.A.; Maluf Filho, F.; de Souza, J.A.U.; Gama-Rodrigues, J. Digestive tract microbiota in healthy volunteers. Clin. Sao Paulo Braz. 2007, 62, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-X.; Wong, G.-H.; To, K.-F.; Wong, V.-S.; Lai, L.H.; Chow, D.-L.; Lau, J.-W.; Sung, J.-Y.; Ding, C. Bacterial microbiota profiling in gastritis without Helicobacter pylori infection or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bik, E.M.; Eckburg, P.B.; Gill, S.R.; Nelson, K.E.; Purdom, E.A.; Francois, F.; Perez-Perez, G.; Blaser, M.J.; Relman, D.A. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Ning, Z.; Mayne, J.; Moore, J.I.; Li, J.; Butcher, J.; Deeke, S.A.; Chen, R.; Chiang, C.-K.; Wen, M.; et al. MetaPro-IQ: A universal metaproteomic approach to studying human and mouse gut microbiota. Microbiome 2016, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, J.J.; Auro, R.; Furlan, M.; Whiteson, K.L.; Erb, M.L.; Pogliano, J.; Stotland, A.; Wolkowicz, R.; Cutting, A.S.; Doran, K.S.; et al. Bacteriophage adhering to mucus provide a non-host-derived immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 10771–10776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aebischer, T.; Fischer, A.; Walduck, A.; Schlötelburg, C.; Lindig, M.; Schreiber, S.; Meyer, T.F.; Bereswill, S.; Göbel, U.B. Vaccination prevents Helicobacter pylori-induced alterations of the gastric flora in mice. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 46, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamsson, I.; Edlund, C.; Nord, C.E. Impact of treatment of Helicobacter pylori on the normal gastrointestinal microflora. CMI 2000, 6, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotoda, T.; Takano, C.; Kusano, C.; Suzuki, S.; Ikehara, H.; Hayakawa, S.; Andoh, A. Gut microbiome can be restored without adverse events after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in teenagers. Helicobacter 2018, 23, e12541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviles-Jimenez, F.; Vazquez-Jimenez, F.; Medrano-Guzman, R.; Mantilla, A.; Torres, J. Stomach microbiota composition varies between patients with non-atrophic gastritis and patients with intestinal type of gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muyzer, G.; Smalla, K. Application of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TGGE) in microbial ecology. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1998, 73, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.T.; Marsh, T.L.; Cheng, H.; Forney, L.J. Characterization of microbial diversity by determining terminal restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 4516–4522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woese, C.R.; Fox, G.E. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: The primary kingdoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5088–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamady, M.; Walker, J.J.; Harris, J.K.; Gold, N.J.; Knight, R. Error-correcting barcoded primers for pyrosequencing hundreds of samples in multiplex. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Engel, P.; Stepanauskas, R.; Moran, N.A. Hidden diversity in honey bee gut symbionts detected by single-cell genomics. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekirov, I.; Russell, S.L.; Antunes, L.C.M.; Finlay, B.B. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 859–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, F.; Bäckhed, F. The gut microbiota-masters of host development and physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterich, W.; Schuppan, D.; Schink, M.; Schwappacher, R.; Wirtz, S.; Agaimy, A.; Neurath, M.F.; Zopf, Y. Influence of low FODMAP and gluten-free diets on disease activity and intestinal microbiota in patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Clin. Nutr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juge, N. Microbial adhesins to gastrointestinal mucus. Trends Microbiol. 2012, 20, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.D.; Van Domselaar, G.; Bernstein, C.N. The gut microbiota in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, S.Y.; Kostopoulos, I.; de Vos, W.M.; Belzer, C. Akkermansia muciniphila in the human gastrointestinal tract: When, where, and how? Microorganisms 2018, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, F. The host-microbe interface within the gut. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2002, 16, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelakkot, C.; Ghim, J.; Ryu, S.H. Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libertucci, J.; Dutta, U.; Kaur, S.; Jury, J.; Rossi, L.; Fontes, M.E.; Shajib, M.S.; Khan, W.I.; Surette, M.G.; Verdu, E.F.; et al. Inflammation-related differences in mucosa-associated microbiota and intestinal barrier function in colonic Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2018, 315, G420–G431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccia, F.; Guggino, G.; Rizzo, A.; Alessandro, R.; Luchetti, M.M.; Milling, S.; Saieva, L.; Cypers, H.; Stampone, T.; Di Benedetto, P.; et al. Dysbiosis and zonulin upregulation alter gut epithelial and vascular barriers in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Geuking, M.B.; Köller, Y.; Rupp, S.; McCoy, K.D. The interplay between the gut microbiota and the immune system. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Magrone, T.; Jirillo, E. The interplay between the gut immune system and microbiota in health and disease: Nutraceutical intervention for restoring intestinal homeostasis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, A.M.; Shanahan, F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macpherson, A.J.; Uhr, T. Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science 2004, 303, 1662–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Poradosu, R.; McLoughlin, R.M.; Lee, J.C.; Kasper, D.L. Bacteroides fragilis-stimulated interleukin-10 contains expanding disease. JID 2011, 204, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuzak, J.; Dillon, S.; Wilson, C. Differential interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-23 production by human blood monocytes and dendritic cells in response to commensal enteric bacteria. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mima, K.; Sukawa, Y.; Nishihara, R.; Qian, Z.R.; Yamauchi, M.; Inamura, K.; Kim, S.A.; Masuda, A.; Nowak, J.A.; Nosho, K.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and T Cells in Colorectal Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellaguarda, E.; Chang, E.B. IBD and the gut microbiota—From bench to personalized medicine. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2015, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irrazábal, T.; Belcheva, A.; Girardin, S.E.; Martin, A.; Philpott, D.J. The multifaceted role of the intestinal microbiota in colon cancer. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawner, K.M.; Morrow, C.D.; Smith, P.D. Gastric microbiome and gastric cancer. Cancer J. 2014, 20, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofgren, J.L.; Whary, M.T.; Ge, Z.; Muthupalani, S.; Taylor, N.S.; Mobley, M.; Potter, A.; Varro, A.; Eibach, D.; Suerbaum, S.; et al. Lack of commensal flora in Helicobacter pylori-infected INS-GAS mice reduces gastritis and delays intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engstrand, L.; Lindberg, M. Helicobacter pylori and the gastric microbiota. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 27, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-K.; Kuo, F.-C.; Liu, C.-J.; Wu, M.-C.; Shih, H.-Y.; Wang, S.S.W.; Wu, J.-Y.; Kuo, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-K.; Wu, D.-C. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection: Current options and developments. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 11221–11235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Jácome, E.; Libânio, D.; Borges-Canha, M.; Galaghar, A.; Pimentel-Nunes, P. Gastric microbiota and carcinogenesis: The role of non-Helicobacter pylori bacteria—A systematic review. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2016, 108, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.-Y.; Tung, S.-Y.; Pan, H.-Y.; Yen, C.-W.; Xu, H.-W.; Lin, Y.-J.; Deng, Y.-F.; Hsu, W.-T.; Wu, C.-S.; Li, C. Increased abundance of Clostridium and Fusobacterium in Gastric microbiota of patients with Gastric cancer in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.A. Gastric cancer: The gastric microbiota—Bacterial diversity and implications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 692–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toprak, N.U.; Yagci, A.; Gulluoglu, B.M.; Akin, M.L.; Demirkalem, P.; Celenk, T.; Soyletir, G. A possible role of Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin in the aetiology of colorectal cancer. CMI 2006, 12, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.; Powell, J.; Mathioudakis, N.; Kane, S.; Fernandez, E.; Sears, C.L. Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin induces intestinal epithelial cell secretion of interleukin-8 through mitogen-activated protein kinases and a tyrosine kinase-regulated nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. Infect. Immuniy 2004, 72, 5832–5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Rhee, K.-J.; Albesiano, E.; Rabizadeh, S.; Wu, X.; Yen, H.-R.; Huso, D.L.; Brancati, F.L.; Wick, E.; McAllister, F.; et al. A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsoi, H.; Chu, E.S.H.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, J.; Nakatsu, G.; Ng, S.C.; Chan, A.W.H.; Chan, F.K.L.; Sung, J.J.Y.; Yu, J. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius induces intracellular cholesterol biosynthesis in colon cells to induce proliferation and causes dysplasia in mice. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1419–1433.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Feng, Q.; Wong, S.H.; Zhang, D.; Liang, Q.Y.; Qin, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhao, H.; Stenvang, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-F.; Ai, L.-Y.; Wang, J.-L.; Ren, L.-L.; Yu, Y.-N.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.-N.; Yu, J.; Li, M.; Qin, W.-X.; et al. Probiotics Clostridium butyricum and Bacillus subtilis ameliorate intestinal tumorigenesis. Future Microbiol. 2015, 10, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacouton, E.; Chain, F.; Sokol, H.; Langella, P.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G. Probiotic strain Lactobacillus casei BL23 prevents colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-W.; Du, P.; Gao, J.; Yang, B.-R.; Fang, W.-R.; Ying, C.-M. Preoperative probiotics decrease postoperative infectious complications of colorectal cancer. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 343, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Xu, L.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Z. Effect of probiotics on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 27, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viaud, S.; Saccheri, F.; Mignot, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Daillère, R.; Hannani, D.; Enot, D.P.; Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Pittet, M.J.; et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science 2013, 342, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daillère, R.; Vétizou, M.; Waldschmitt, N.; Yamazaki, T.; Isnard, C.; Poirier-Colame, V.; Duong, C.P.M.; Flament, C.; Lepage, P.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Enterococcus hirae and Barnesiella intestinihominis facilitate cyclophosphamide-induced therapeutic immunomodulatory effects. Immunity 2016, 45, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-producing colon bacteria: Importance and strategies for their stimulation in the human gut. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganji-Arjenaki, M.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. Probiotics are a good choice in remission of inflammatory bowel diseases: A meta analysis and systematic review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 2091–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartor, R.B.; Wu, G.D. Roles for intestinal bacteria, viruses, and fungi in pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases and therapeutic approaches. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 327–339.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Lee, W.S.; Mitchell, H.M. Dual role of Helicobacter and Campylobacter species in IBD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2017, 66, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murad, H.A. Does Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy trigger or protect against Crohn’s disease? Acta Gastro-Enterol. Belg. 2016, 79, 349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, I.R.; Milosavjevic, T.N.; Jankovic, G.P.; Micev, M.M.; Dugalic, P.D.; Saranovic, D.; Ugljesic, M.M.; Popovic, D.V.; Bulajic, M.M. Clinical onset of the Crohn’s disease after eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection. Does Helicobacter pylori infection interact with natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases? Med. Sci. Monit. 2001, 7, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tursi, A. Onset of Crohn’s disease after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2006, 12, 1008–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahat, A.; Neuman, S.; Levhar, N.; Yablecovitch, D.; Avidan, B.; Weiss, B.; Ben-Horin, S.; Eliakim, R. Helicobacter pylori prevalence and clinical significance in patients with quiescent Crohn’s disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichon, M.; Lina, B.; Josset, L. Impact of the respiratory microbiome on host responses to respiratory viral infection. Vaccines 2017, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analytical Method | Pathophysiological Context | Modification in Bacterial Abundance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture method | Healthy patient | Veillonella sp., Lactobacillus sp., Clostridium sp. Propionibacterium, Streptococcae and Staphylococcae | Zilberstein et al. 2007 [19] |

| 16S rRNA sequencing | Proteobacteria, Firumicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Fusobacteria (Streptococcae and Prevotella) | Li et al. 2009 [20] Bik et al. 2006 [21] | |

| Molecular biology | Mice models | Increase in Clostridia, Bacteroides/Prevotella spp., Eubacterium spp., Ruminococcus spp., Streptococci and Escherichia coli Decrease in Lactobacilli | Aebischer et al. 2006 [24] |

| 16S rRNA microarray | Chronically infected patient | Decrease of Actinobacteriae, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes Increase of Spirochetes, acidobacteriae and Proteobacteriae | Moldonado-Contreras et al. 2011 [10] |

| Culture method | Under-therapies patients | Decrease of Bifidobacteria or Clostridia. Increase of Enterococci, Enterobacteria and Peptostreptococci | Adamson et al. 2000 [25] |

| 16S rRNA sequencing | Under-therapies patients | Increase of Bacteroidetes Decrease Actinobacteria, Bifidobacteriales No modification of Lactobacillus | Gotoda et al. 2018 [26] |

| 16S rRNA sequencing | Gastritis | Decrease of Proteobacteria (phyla) and of Prevotella (level) Increase of Firmicutes (phyla) and of Streptococcus (genera) | Li et al. 2009 [20] |

| 16S rRNA microarray | Invasive gastric cancer | Decrease in Porphyromonas, Neisseria and Streptococcus sinensis Increase in Lactobacillus L. coleohomonis and Lachnospiraceae | Aviles-Jimenez et al. 2014 [27] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pichon, M.; Burucoa, C. Impact of the Gastro-Intestinal Bacterial Microbiome on Helicobacter-Associated Diseases. Healthcare 2019, 7, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010034

Pichon M, Burucoa C. Impact of the Gastro-Intestinal Bacterial Microbiome on Helicobacter-Associated Diseases. Healthcare. 2019; 7(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010034

Chicago/Turabian StylePichon, Maxime, and Christophe Burucoa. 2019. "Impact of the Gastro-Intestinal Bacterial Microbiome on Helicobacter-Associated Diseases" Healthcare 7, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010034