The Common Values of Social Media Marketing and Luxury Brands. The Millennials and Generation Z Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

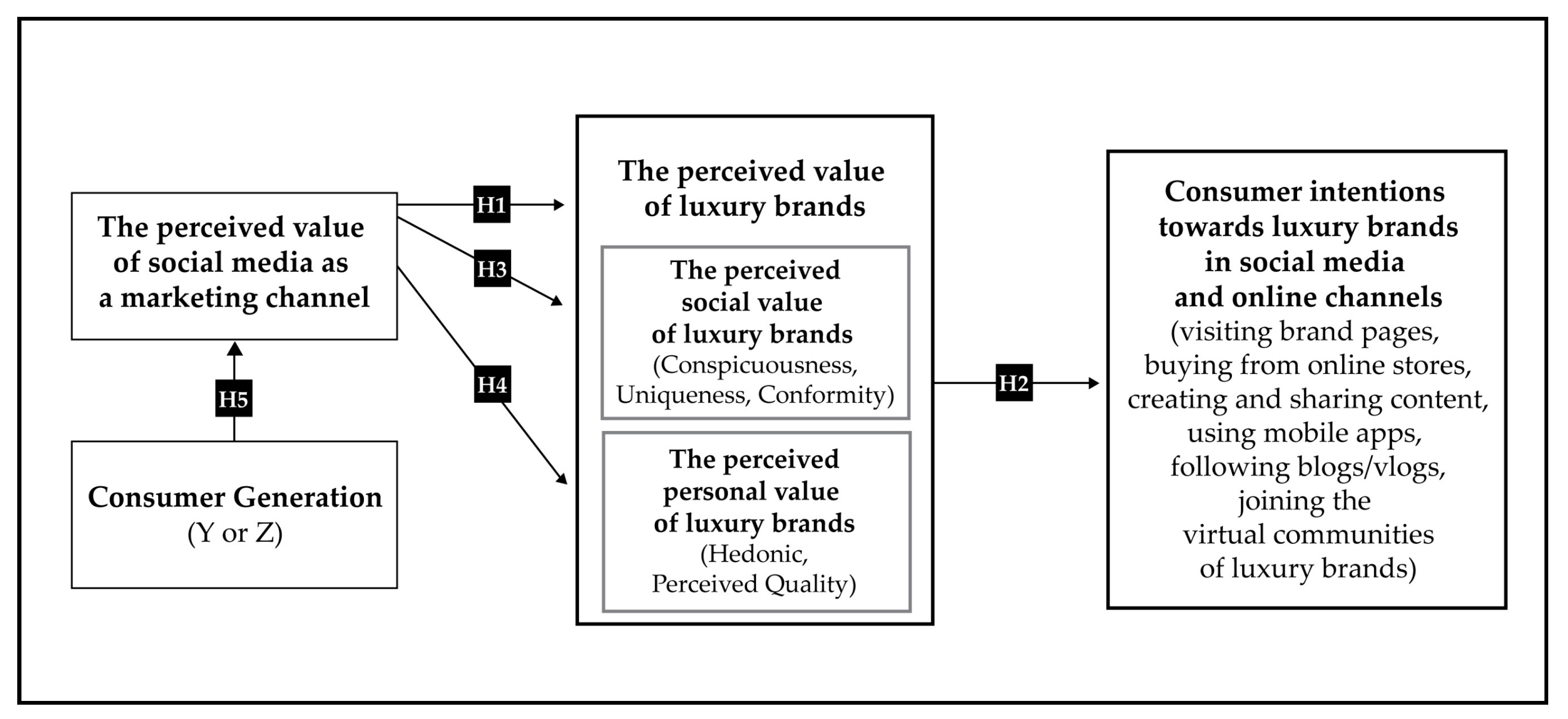

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement Scale

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

4. Results

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research Lines

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| People buy famous luxury brands to attract the attention of the people around them. |

| Many people buy luxury brands to stand out. |

| People buy luxury brands just to show their superior social status. |

| Buying an expensive product makes you feel more valuable. |

| People prefer to let their peers know that the luxury brands they buy are expensive. |

| People buy luxury brands to be different from their peers. |

| I think the luxury brands that a lot of people can afford are less valuable. |

| People are all the more attracted to luxury brands the rarer they are. |

| I like to buy luxury brands that have recently appeared on the market before others. |

| A valuable luxury product should not be sold in regular stores. |

| People buy luxury brands to look like those around them (friends, neighbors, family). |

| I like to know the opinion of others when I buy expensive products. |

| I often ask friends, colleagues, family for information to buy a luxury brand. |

| People want to buy brands bought by rich or famous people even though they don’t show it. |

| Buying and using luxury brands makes our lives more beautiful. |

| When I buy a luxury product I feel that it offers me a personal reward (I tell myself: * I deserve it too *). |

| The special aesthetics of luxury brands delights our senses. |

| When I buy a luxury brand, it gives me pleasure, I don’t think about the feelings of those around me. |

| Superior performance is the main reason for buying luxury brands (quality of materials, durability, sophistication, elegance). |

| True luxury brands cannot be mass-produced, only handcrafted. |

| Luxury brands are functionally superior to other brands. |

| I am constantly following the achievements of luxury brands in terms of design and technology. |

| I would not buy a luxury brand at a lower price than I expected. |

| People buy luxury brands at high prices because they are sure of their excellent quality. |

| On social networking sites I find the information I need about luxury brands. |

| On social networking sites I find information on luxury brands that I can’t find in other sources. |

| A means by which I can find out and benefit from the promotions offered and make efficient purchases. |

| Social networking sites keep me up to date with the latest luxury trends (launches of new models, new collections, styles, etc.). |

| The information on social networking sites is reliable because it comes from people who have used the product. |

| The information on social networking sites is reliable because it comes from people I know. |

| Social networking sites help me get a clear idea of luxury brands and their image. |

| It gives me the opportunity to have a closer connection with my favorite brand. |

| It helps me communicate directly and in a personalized manner with my favorite luxury brands. |

| It gives me the opportunity to send private messages to luxury companies (requests, complaints). |

| It helps me learn about the experiences of others regarding my favorite luxury brands. |

| It gives me the opportunity to read reviews, comments from other “fans” of luxury brands. |

| It gives me the opportunity to participate in informal fan groups created by other consumers of luxury brands. |

| It gives me the opportunity to make my tastes known, my refinement when I get involved in conversations about luxury brands. |

| It gives me the opportunity to post comments in the luxury brand page timeline and I can be useful to other fans. |

| It gives me the opportunity to demonstrate my creativity and originality to other luxury consumers. |

| It offers me the opportunity to customize the ordered products. |

| It gives me the opportunity to have control of my interactions in social networks. |

| The social networking sites of luxury brands make me feel special. |

| I like to participate in conversations on social networks of luxury brands. |

| It’s fun to participate in creating content on the social networks of luxury brands. |

| I plan to buy my favorite luxury brands from online stores in the future. |

| I intend to continue visiting the websites of luxury brands. |

| I intend to use the applications on the websites of my favorite luxury brands. |

| I plan to continue participating on the social networks of luxury brands (to post comments, images, videos, likes to the content posted). |

| I intend to follow the vlogs/blogs of luxury companies or blogs that refer to luxury brands. |

| I will join virtual communities of luxury brands. |

References

- Keinan, A.; Crener, S.; Bellezza, S. Luxury Brand Research. New Perspectives and futures Priorities. Wharton University of Pennsylvania, Baker Retailing Center, Report Online Luxury Retailing: Leveraging Digital Opportunities. Research, Industry Practice and Open Questions. 2016. Available online: https://bakerretail.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Online_Luxury_Retail.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2017).

- Achille, A.; Marchessou, S.; Remy, N. Luxury in the Age of Digital Darwinism. 2018. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.it/idee/luxury-in-the-age-of-digital-darwinism (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Arienti, P. Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2018, Shaping the Future of the Luxury Industry. 2018. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/at/Documents/consumer-business/deloitte-global-powers-of-luxury-goods-2018.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2019).

- D’Arpizio, C.; Levato, F.; Kamel, M.-A.; de Montgolfier, J. Insights: The New Luxury Consumer: Why Responding to the Millennial Mindset Will Be Key. 2017. Available online: https://www.bain.com/insights/luxury-goods-worldwide-market-study-fall-winter-2017 (accessed on 21 September 2018).

- Athwal, N.; Istanbulluoglu, D.; McCormack, S.E. The allure of luxury brands’ social media activities: A uses and gratifications perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, O.; Velasco, C.; Spence, C. Digital Sensory Marketing: Integrating New Technologies into Multisensory Online Experience. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arrigo, E. Social media marketing in luxury brands: A systematic literature review and implications for management research. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Ashill, N.; Amer, N.; Diab, E. The internet dilemma: An exploratory study of luxury firms’ usage of internet-based technologies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alamoudi, H. How External and Mediating Factors Affect Consumer Purchasing Behaviour in Online Luxury Shopping. Ph.D. Thesis, Plymouth University, Plymouth, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behaviour. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuckels, E.; Hudders, L. An experimental study to investigate the impact of image interactivity on the perception of luxury in an online shopping context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ordabayeva, N.; Cavanaugh, L.A.; Dahl, D.; Azoulay, A.; Coste-Maniere, I.; Jurney, J.; Erkhova, D. Luxury in the Digital World. How Digital Technology Can Complement, Enhance, and Differentiate the Luxury Experience. Online Luxury Retailing: Leveraging Digital Opportunities. Research, Industry Practice and Open Questions. Available online: https://bakerretail.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Online_Luxury_Retail.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2019).

- Kluge, P.N.; Fassnacht, M. Selling luxury goods online: Effects of online accessibility and price display. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, N.; Wiedeman, K.P.; Klarman, C. Luxury brands in the digital age-exclusivity versus ubiquity. Mark. Rev. St. Gallen 2012, 29, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Impacts of Luxury Fashion Brand’s Social Media Marketing on Customer Relationship and Purchase Intention. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2010, 1, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, U. Sustaining the Luxury Brand on the Internet. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 16, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sortheix, F.M.; Lönnqvist, J.-E. Personal value priorities and life satisfaction in Europe. The moderating Role of socioeconomic development. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulruf, B.; Alesi, M.; Ciochina, L.; Faria, L.; Hattie, J.; Hong, F.; Pepi, A.-M.; Watkins, D. Measuring collectivism and individualism in the third millennium. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2011, 39, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D. Psihologia Poporului Roman: Profilul Psihologic al Românilor Într-O Monografie Cognitiv-Experimentală; Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, S. Impact of Personal Orientation on Luxury-Brand Purchase Value: An International Investigation. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 47, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. A review and a conceptual framework of prestige-seeking consumer behavior. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 1999, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. Measuring Perceptions of Brand Luxury. J. Brand Manag. 2004, 11, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.R. The influence of perceived social media marketing activities on brand loyalty: The mediation effect of brand and value consciousness. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G. Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabash, S.; Ma, M. A Tale of Four Platforms: Motivations and Uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat among College Students? Soc. Media Soc. 2017, 3, 2056305117691544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, S.; Filieri, R.; Gorton, M. Customers’ motivation to engage with luxury brands on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzeta, C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N. Motivations to use different social media types and their impact on consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRAs). J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 52, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentina, I.; Guilloux, V.; Micu, A.C. Exploring Social Media Engagement Behaviors in the Context of Luxury Brands. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Czellar, S.; Laurent, G. Consumer segments based on attitudes toward luxury: Empirical evidence from twenty countries. Mark. Lett. 2005, 16, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, H.R.; Majumdar, S. Of Diamonds and Desires: Understanding Conspicuous Consumption from a Contemporary Marketing Perspective. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2006, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Paul, J. Mass prestige value and competition between American versus Asian laptop brands in an emerging market—Theory and evidence. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Covered in Gold: Examining gold consumption by middle class consumers in emerging markets. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Rosendo-Rios, V. Intra and inter-country comparative effects of symbolic motivations on luxury purchase intentions in emerging markets. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Laurent, G. Attitudes toward the Concept of Luxury: An Exploratory Analysis. Asia Pacific. Adv. Consum. Res. 1994, 1, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, J.N.; Bastien, V. The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands, 2nd ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, S.; Caruana, R.; Medway, D.; Murphy, P. Constructing luxury brands: Exploring the role of consumer discourse. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwedt, G.; Chevalier, M.; Gutsatz, M. Luxury Retail Management: How the World’s Top Brands Provide Quality Product and Service Support; John Wiley & Sons: Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chandon, J.L.; Laurent, G.; Valette -Florence, P. Pursuing the concept of luxury: Introduction to the JBR Special Issue on Luxury Marketing from Tradition to Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, Y. Web atmospheric qualities in luxury fashion brand websites. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 384–401. [Google Scholar]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.; Thomas, R.; Heine, K. Social Media and Luxury Brand Management: The Case of Burberry. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2011, 2, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M. Social media and luxury fashion brands in China: The case of Coach. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2014, 5, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Lu, H. Why do people play online games? An extended TAM with social influences and flow experience. J. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Huang, L.; Roth, M.S.; Madden, T.J. The influence of social media interactions on consumer–brand relationships: A three-country study of brand perceptions and marketing behaviors. International. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohm, A.; Kaltcheva, V.D.; Milne, G.R. A mixed-method approach to examining brand-consumer interactions driven by social media. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2013, 7, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Exploring Customer Brand Engagement: Definition and Themes. J. Strat. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-H.S.; Men, L.R. Consumer engagement with brands on social network sites: A cross-cultural comparison of China and the USA. J. Mark. Commun. 2017, 23, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.; Kaltcheva, V.D.; Rohm, A.J. Hashtags and handshakes: Consumer motives and platform use in brand-consumer interactions. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shin, H.; Burns, A.C. Examining the impact of luxury brand’s social media marketing on customer engagement: Using big data analytics and natural language processing. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 815–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-E.; Lloyd, S.; Cervellon, M.-C. Narrative-transportation storylines in luxury brand advertising: Motivating consumer engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Hun, H.; Thavisay, T. A study of antecedents and outcomes of social media WOM towards luxury brand purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Giannakos, M.; Pateli, A. Shopping and Word-of-Mouth Intentions on Social Media. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 8, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kefi, H.; Maar, D. The power of lurking: Assessing the online experience of luxury brand fan page followers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A.; Chiang, L.; Tang, L. Identifying and responding to customer needs on Facebook Fan pages. Int. J. Technol. Hum. Interact. 2013, 9, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Courtois, C.; Mechant, P.; De Marez, L.; Verleye, G. Gratifications and seeding behaviour of online adolescents. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2009, 15, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jahn, B.; Kunz, W.; Meyer, A. The Role of Social Media for Luxury-Brands—Motives for Consumer Engagement and Opportunities for Businesses. In Identitätsbasierte Luxusmarkenführung; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-8349-4060-5_14 (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Verduyn, P.; Lee, D.; Park, J.; Shablack, H.; Orvell, A.; Bayer, J.; Ybarra, O.; Jonides, J.; Kross, E. Passive Facebook Usage Undermines Affective Well-Being: Experimental and Longitudinal Evidence. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahlhoff, D. The Challenge for Luxury Retailers: Figuring out Digital Opportunities. Online Luxury Retailing: Leveraging Digital Opportunities: Research, Industry Practice and Open Questions. 2016. Available online: https://bakerretail.wharton.upenn.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/06/Online_Luxury_Retail.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Tynan, C.; McKechnie, S.; Chhuon, C. Co-Creating Value for Luxury Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, K.; Stephen, A.T. Are close friends the enemy? Online social networks, self-esteem, and self-control. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonzales, A.L.; Hancock, J.T. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: Effects of Facebook exposure on self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoumrungroje, A. The Influence of Social Media Intensity and EWOM on Conspicuous Consumption. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilcox, K.; Kramer, T.; Sen, S. Indulgence or self-control: A dual process model of the effect of incidental pride on indulgent choice. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Chu, S.-C.; Pedram, M. Materialism, attitudes, and social media usage and their impact on purchase intention of luxury fashion goods among American and Arab young generations. J. Interact. Advert. 2013, 13, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; Buil, I.; de Chernatony, L. Consuming good’ on social media: What can conspicuous virtue signalling on Face-book tell us about prosocial and unethical intentions? J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creevey, D.; Coughlan, J.; O’Connor, C. Social media and luxury: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abosag, I.; Ramadan, Z.; Baker, T.; Jin, Z. Customers’ need for uniqueness theory versus brand congruence theory: The impact on satisfaction with social network sites. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, N.; Wiedmann, K.P.; Klarmann, C.; Behrens, S. The complexity of value in the luXury industry. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Hudders, H.; Cauberghe, V. Selling luxury products online: The effect of a quality label on risk perception, purchase intention and attitude toward the brand. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 19, 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bain & Company’s Annual Luxury Study (17th ed.). Available online: https://www.bain.com/about/media-center/press-releases/2018/fall-luXury-goods-market-study/ (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Paul, J. Masstige model and measure for brand management. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazon, M.; Sicilia, M.; López, M. The influence of “Facebook friends” on the intention to join brand pages. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2015, 24, 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Menendez, A.; Palos-Sanchez, P.; Saura, J.R.; Santos, C.R. Revisiting the impact of perceived social value on consumer behavior toward luxury brands. Eur. Manag. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strutton, D.; Taylor, D.G.; Thompson, K. Investigating generational differences in e-WOM behaviours: For advertising purposes, does X = Y? Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneidinger, B. Intergenerational contacts online: An exploratory study of cross-generational Facebook “friendships”. Stud. Commun. Sci. 2014, 14, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennial Marketing: Millennials Want Deals, Not Discounts. Available online: https://www.millennialmarketing.com/2010/08/millennials-want-deals-not-discounts/ (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J.; Schouten, A.P. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Walkins, B. YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5753–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Turley, L. Malls and consumption motivation: An exploratory examination of older Generation Y consumers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2004, 32, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. Digital marketing strategies that millennials find appealing, motivating, or just annoying. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, S.; Adam, M. The influence of social networking site on buying behaviours of millennials. Atlantic Mark. J. 2013, 2, 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, R.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Hoefnagels, A.; Migchels, N.; Kabadayi, S.; Gruber, T.; Komarova Loureiro, Y.; Solnet, D. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamawaki, M.A.; Sarfati, G. The Millennials Luxury Brand Engagement on Social Media: A Comparative Study of Brazilians and Italians. Rev. Int. Bus. 2019, 14, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Immordino-Yang, M.H.; Christodoulou, J.A.; Singh, V. Rest is not Idleness: Implications of the Brain’s Default Mode for Human Development and Education. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, K.; Page, R.A. Marketing to the generations. J. Behav. Stud. Bus. 2011, 3, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, D.; Touzani, M.; Ben Slimane, K. Marketing to the (new) generations: Summary and perspectives. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priporas, C.-V.; Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A.K. Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing: A future agenda. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.; van Stolk-Cooke, K.; Muench, F. Understanding Facebook use and the psychological effects of use across generations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofides, E.; Muise, A.; Desmarais, S. Hey Mom, what’s on your Facebook? Comparing Facebook disclosure and privacy in adolescents and adults. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2012, 3, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAndrew, F.T.; Jeong, H.S. Who does what on Facebook? Age, sex, and relationship status as predictors of Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2359–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, J.L.; Clayton, R.B. Instagram unfiltered: Exploring associations of body image satisfaction, instagram #selfie posting, and negative romantic relationship outcomes. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffey, D. Global Social Media Research Summary 2017, Smart Insights. Available online: http://www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-strategy/new-global-social-media-research (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Dumas, T.M.; Maxwell-Smith, M.; Davis, J.P.; Giulietti, P.A. Lying or longing for likes? Narcissism, peer belonging, loneliness and normative versus deceptive like-seeking on Instagram in emerging adulthood. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Durán, J.J. Defining generational cohorts for marketing in Mexico. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosdahl, D.J.C.; Carpenter, J.M. Shopping orientations of US males: A generational cohort comparison. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovation Report, Samsung. 2020. Available online: https://techzilla.ro/samsung-innovation-report-2020 (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Eurostat, Population Age Structure by Major Age Groups, 2007 and 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Population_age_structure_by_major_age_groups,_2007_and_2017_(%25_of_the_total_population).png (accessed on 23 September 2018).

- Next Generation or Lost Generation? Children, Young People and the Pandemic EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/659404/EPRS_BRI(2020)659404_EN.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Overby, J.W.; Lee, E.J. The Effects of Utilitarian and Hedonic Online Shopping Value on Consumer Preference and Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeby, D. The Construction of Experience: Interface as Content, Digital Illusion: Entertaining the Future With High Technology; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brasel, S.A.; Gips, J. Tablets, Touchscreens, and Touchpads: How Varying Touch Interfaces Trigger Psychological Ownership and Endowment. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Burns, A.C.; Hou, Y. Comparing online and in-store shopping behavior towards luxury goods. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Be creative, my friend! Engaging users on Instagram by promoting positive emotions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Opreana, A. Social Media Efforts of Luxury Brands on Instagram. Expert J. Mark. 2019, 7, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Eng, T.Y.; Bogaert, J. Psychological and cultural insights into consumption of luxury Western brands in India. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allison, G. A Cross-Cultural Study of Motivation for Consuming Luxuries. Ph.D. Thesis, Lincoln University, Lincolnshire, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, M.; Harris, J. The Desire for Unique Consumer Products: A New Individual Differences Scale. Psychol. Mark. 1997, 14, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, M.H. Les Facteurs Explicatifs De La Consommation Ostentatoire Des Produits De Luxe—Le Cas Du Liban. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paris XII Val de Marne, Créteil, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of Consumer Attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, M.F. Purchase and Consumption of Luxury Product. Ph.D. Thesis, University Carlos III de Madrid, Getafe, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. It is not for fun: An examination of social network site usage. Inf. Manag. 2012, 49, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heinonen, K. Consumer Activity in Social Media: Managerial Approaches to Consumers’ Social Media Behavior. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriu, R.; Guesalaga, R. Consumers’ social media brand behaviours: Uncovering underlying motivators and deriving meaningful consumer segments. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Construct | Cronbach α | KMO | Bartlett | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The perceived value of social media | 0.787 | 0.687 | 210.69 | 0.000 |

| The perceived value of online luxury brands | 0.542 | 0.500 | 32.66 | 0.000 |

| The social value of luxury | 0.539 | 0.500 | 32.40 | 0.000 |

| The personal value of luxury | 0.707 | 0.500 | 78.21 | 0.000 |

| Consumer intentions | 0.880 | 0.500 | 38.58 | 0.000 |

| H | Description | Unstandardized Coefficients (β) | R2 | T | (p) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | The perception of social media sites value → perceived value of luxury brands | 0.342 | 0.180 | 6.893 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2 | The perceived value of luxury brands → consumer intentions | 0.641 | 0.178 | 6.882 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3 | The perceived value of social media → perceived personal value of luxury brands | 0.372 | 0.129 | 5.639 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4 | The perceived value of social media → perceived social value of luxury brands | 0.313 | 0.115 | 5.298 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5 | Generation → The perceived value of social media | - | - | 0.548 | 0.584 | Rejected |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dobre, C.; Milovan, A.-M.; Duțu, C.; Preda, G.; Agapie, A. The Common Values of Social Media Marketing and Luxury Brands. The Millennials and Generation Z Perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2532-2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070139

Dobre C, Milovan A-M, Duțu C, Preda G, Agapie A. The Common Values of Social Media Marketing and Luxury Brands. The Millennials and Generation Z Perspective. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2021; 16(7):2532-2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070139

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobre, Costinel, Anca-Maria Milovan, Cristian Duțu, Gheorghe Preda, and Amadea Agapie. 2021. "The Common Values of Social Media Marketing and Luxury Brands. The Millennials and Generation Z Perspective" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16, no. 7: 2532-2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070139

APA StyleDobre, C., Milovan, A.-M., Duțu, C., Preda, G., & Agapie, A. (2021). The Common Values of Social Media Marketing and Luxury Brands. The Millennials and Generation Z Perspective. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(7), 2532-2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070139