1. Introduction

Internet access and the usage of mobile phones have reshaped human behavior and expectations, as well as customer relations with brands. Empowered consumers now expect to connect with brands and live a seamless experience across touchpoints. Moreover, consumers switch from one channel to another or one touchpoint to another depending on the context, resulting in an omnichannel behavior [

1]-with ‘omnis’ stemming from the latin for ‘every’ or ‘all’. These changes in consumer behavior, as well as advances in digital technologies and innovations, have led to the emergence of new channels, especially digital ones. Nevertheless, adding new channels and touchpoints to allow customers to interact with organizations is meaningless if these interactions are not integrated and articulated at a customer level. If multichannel was a synonym of enabling and managing different channels, an omnichannel approach for customer experience (CX) means that these channels are integrated and therefore the customer experiences a seamless interaction with the brand, with meaningful transitions. In this context, omnichannel management is “the synergetic management of the numerous available channels and customer touchpoints, in such a way, that the customer experience across channels and the performance over channels is optimized” [

1].

Customer experience is critical as a strategy for differentiation in a highly competitive global market in which the customer increasingly has more options and the cost to get a different alternative is extremely low. Moreover, experience quality has an impact on customers’ omnichannel shopping intention [

2]. With Internet pure players such as Google, Apple, Facebook, or Amazon becoming direct potential competitors for almost every traditional organization, understanding customer behavior in order to design an omnichannel strategy has become essential. Additionally, some customer behaviors—such as online shopping—have fundamentally changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic [

3]. Consequently, organizations have had to rapidly adapt, and digital transformation, as well as omnichannel CX, have gone from buzzwords to top priorities.

There is rising interest in omnichannel management among practitioners and academia [

4,

5], e.g., in the management and retail research areas [

6,

7,

8], in which studies address consumer behavior concepts such as shopping channel choice and shopping value. From the academic perspective, there is a focus on the company and its organizational challenges, e.g., the integration of distribution channels [

7], cultural change [

9], and technological implementations of enterprise software [

10]. Recent research addresses both the consumer and the practitioner’s perspective on topics such as integration [

11,

12], in addition to bridging the gap where there is a lack of well-accepted definitions [

13]. However, based on a recent systematic literature review [

14], there is a research gap in documented business cases as well as existing omnichannel frameworks: the transition process from multichannel to omnichannel has been poorly explored, and further practical and theoretical research is needed. The goals of our research are, therefore, to (1) understand the key factors that enable unlocking omnichannel capabilities, (2) identify the challenges of becoming an omnichannel service-based organization, and (3) propose a set of strategies to overcome them.

Technology has long been a fundamental piece of the operationalization of omnichannel strategies. Nevertheless, as a part of a digital transformation process, going omnichannel requires managers to completely rethink their company’s approach to clients and eventually even broaden the perspective to the entire business ecosystem. Knowing that technology is not a barrier anymore, the question is how and where do we start? How do we get to a CX-driven approach? What else does it take besides integrated channels? In this context, stakeholders each approach omnichannel management from their own perspective. In this paper, we adopt a CX management-driven approach for omnichannel management in a service context. The objective of our study is to gain a deeper understanding of the transition process from multichannel to omnichannel management for service-based organizations. As current research in omnichannel management concentrates on the retail industry, we focus on service-based companies.

A previous literature review found a lack of documented business cases coming from Latin America (LATAM) in general and Chile in particular [

14]. As the organizational capabilities and willingness to implement strategies and tactics are highly related to the context, best practices or frameworks emerging from the Chilean context might fit the actual context of LATAM organizations at a regional level. As most of the participants work at international companies and are involved in global projects, insights gathered during this research are valuable in the context of both emerging and advanced economies. Beyond understanding the local context, the goal of our study is to raise global research questions and propose practical recommendations that would benefit service organizations in a wide range of economic realities. In order to gain insights into this seldom studied geographical area, we conducted eleven semi-structured interviews with Chilean practitioners before the COVID-19 pandemic and then online group interviews were used to validate our model and gather additional insights during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This paper is organized as follows. First, we explain the research design, followed by the data analysis. Next, we introduce the conceptual framework our study unveiled. Finally, we conclude with managerial and academic implications, limitations, and future research directions.

2. The Study

We adopted an exploratory qualitative approach, with the goal of understanding how organizations approach customer experience management and evaluation in an omnichannel context. With this research objective in mind, we designed an interview protocol. However, based on the first interviews-before the COVID-19 pandemic, it became clear that most teams were not perceiving their organization as omnichannel. They were rather undergoing the process of changing an organizational customer orientation from being multichannel to omnichannel. Therefore, we defined our research question as: “What are the characteristics of the transition process from multichannel to omnichannel CX?” Based on this research question, we reframed our research goals so they centered on understanding this process, which resulted in an initial framework representing the enablers, challenges, and contextual factors that organizations encounter during this transition. Following this first study, we submitted the framework to validation by practitioners through group interviews. Additionally, as these interviews were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, a fundamental component of the framework emerged: the drivers for transitioning from multichannel to omnichannel (this transformation process was accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic).

2.1. Method

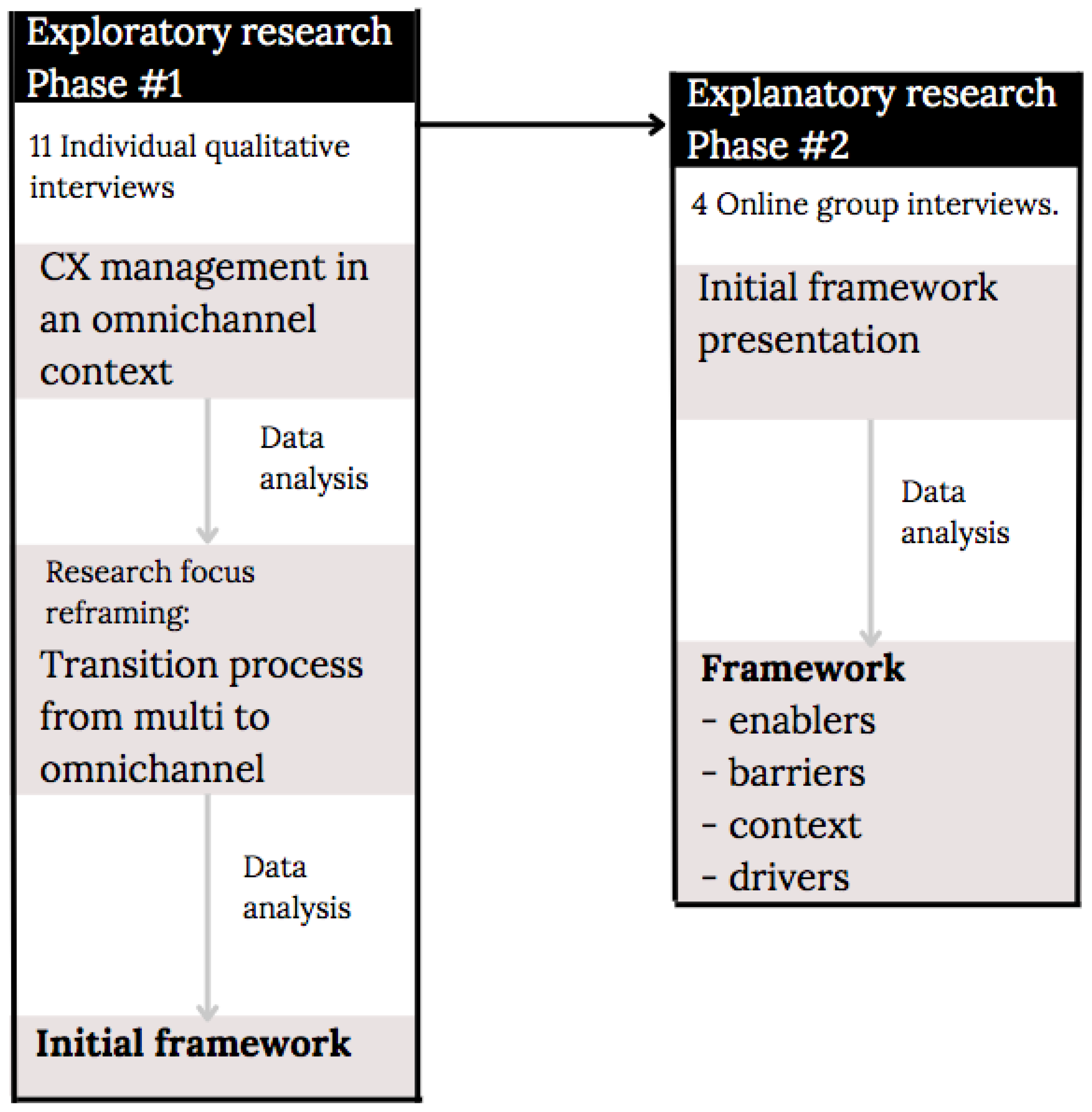

The research methodology is shown in

Figure 1. As shown, our approach consisted of two phases: (1) an exploratory research phase, consisting of individual qualitative interviews, with the goal of understanding initial participant experience and opinions; and (2) an explanatory research phase, consisting of online group interviews, to validate our model and gather additional insights. Each phase is described in detail in

Section 2.1.1 and

Section 2.1.2.

2.1.1. Individual Qualitative Interviews

In the first phase, we used semi-structured interviews to collect data from a field-based perspective. Semi-structured interviews allow participants to discuss their opinions at length and share past experiences, providing researchers with a deep understanding of the meanings participants make of their experiences and allowing for the comprehension of the phenomenon under study [

15].

Although the initial focus was to understand CX in an omnichannel context, we discussed strategies and gaps that need to be addressed in order to support organizations during the process to transition from a multichannel to an omnichannel organization (see

Appendix A). Beyond the specific questions, we aimed at creating a trust space for an inquiry-based conversation. In qualitative research, having a small set of broad questions facilitates conversation in order to capture the participant’s experience [

16]. The interviews took place in-person, before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The protocol of the interviews was structured as follows and is presented in its entirety in

Appendix A:

The main researcher welcomed the participant, presented the topic and had the participants give informed consent to the interview.

As an initial question to contextualize the interview, the main researcher asked the interviewee to describe their role in the company.

Participants were asked about how they approach customer experience in the organization.

Next, they were asked about the omnichannel experience in their organization, and in this conversation the discussion turned to how the organization is working to become omnichannel.

Finally, they were asked if they would like to know about the findings of the research and to potentially participate in a follow-up study.

The interviews in this first phase of the study lasted 30 to 60 min and were recorded in audio and transcribed. We explain this process in

Section 2.3.

2.1.2. Online Group Interviews

The results from the first exploratory phase allowed us to build an initial framework of enablers, challenges, and contextual factors. Then, in the second phase of this study, we presented this initial framework to omnichannel, customer experience practitioners, and consultants, in online group interviews, in order to validate the acceptance of the model and gather additional insights on the enablers of the transition to omnichannel and the accelerated process they have faced during 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The protocol of the group sessions was structured as follows and is presented in its entirety in

Appendix B.

The main researcher welcomed the participants, presented the topic and had participants give informed consent to their participation.

Participants were encouraged to introduce themselves to the group and share their experiences with transitioning to omnichannel.

The researcher introduced the framework and asked participants about their opinions, based on their own expertise and organizational reality.

The researcher then asked the participants how we can support this transition process.

2.2. Participants

During the first phase, participants were six women and five men. Eight of the participants work for companies that have international operations. Nine have corporate positions in telecommunications, insurance, and the banking industry, while the other two are consultants with previous corporate experience that are currently involved in consulting projects on customer experience.

In order to select the first participants, we used the professional network of the first author, meaning it was a convenience sampling. The first interviewees were recommended by senior management contacts in each company. These first participants subsequently invited their colleagues to the study, based on their corporate role connection with the research topic. As per the number of participants, we sought data saturation, meaning “the point in data collection and analysis when new incoming data produces little or no new information to address the research question” [

17], which is generally used in qualitative research to assess sample sizes. At this stage of our research, data saturation was reached at the eleventh interview. Previous research has shown that even a smaller sample (6–7 interviews) allows one to reach 80% data saturation, and 11–12 interviews are typically needed [

17,

18]. A similar study shows that data saturation in qualitative research is reached after 9–17 interviews or 4–8 focus group discussions [

19].

For the second phase, participants from the first phase were invited to participate again, which two participants accepted, and new participants were recruited through an open LinkedIn call. Thirteen practitioners from four countries (Chile, Mexico, Argentina, and Ecuador) attended the three sessions.

Figure 2 gives an overview of our participants’ background.

2.3. Data Analysis

After the first phase of the study, the semistructured interviews were transcribed by a research assistant in their entirety, resulting in 82 pages of single-spaced text. The transcribed data were coded by the first researcher in its original language (Spanish) and analyzed using the Atlas.ti software. For this end, to analyze the qualitative data, we applied thematic analysis based on the guide proposed by Braun and Clarke [

20].

As a first step in qualitative analysis, the researcher read the transcripts to become familiar with the data. Then, the researcher began the process of open coding, which includes labeling units of meaning that capture significant data regarding the main research subject, which in this case is omnichannel customer experience evaluation and management. Due to the fact that the first coding scheme was quite complex, the researcher had to review the codes and consolidate them into a shorter list. Codes were not pre-set but rather emerged during the process. As Braun and Clarke mention, there was an overlap between the coding step and the identification of themes. The researcher then grouped these codes in thematic categories that represent the components of the framework that we describe in the next section. In this phase, the categories and codes were discussed among researchers and refined. As a result, an initial version of the framework emerged.

The framework was then submitted to discussion during the second study in order to capture the participants’ perceptions of the transition process. The discussion was entirely transcripted and coded following the same guidelines [

20]. One new theme emerged during this process; therefore, we added it to the framework: the drivers of the transitioning process.

Once the coding process was completed, the results—meaning the codes and unveiled themes—were translated into English by the authors. Similarly, relevant quotes were translated into English by the authors for the purposes of this paper.

The framework we present in the next section is the final version, incorporating the analyzed data from both phases of the study.

3. A Framework of the Transition Process from Multichannel to Omnichannel Customer Experience Management

A conceptual framework for multichannel to omnichannel transition emerged from our study, mapping the factors influencing the evolutive process from a multichannel to an omnichannel service organization. The framework (

Figure 3) captures the enablers, barriers, and contextual factors that shape the market landscape for service-oriented businesses. A summary of the framework is presented in

Table 1. The business and social context can be an accelerator of the process, as the recent pandemic has shown. In this section, we present our findings and illustrate each aspect with quotes from the interviewees. Each participant is identified as P1, P2, etc.

3.1. Enablers of the Transition Process

Enablers are factors that facilitate the adoption of omnichannel CX management at both a strategic and operational level. In the first phase of the study, while coding the participants’ transcripts, we identified several enablers for this transitioning process from multichannel to omnichannel. First, there is the adoption of a strategic customer-centric mindset at scale, meaning omnichannel adoption cannot occur if the organization is not top-down aligned for this purpose. Second, the organization must strive for brand customer-centric outcomes throughout the customer journey. Third, these outcomes must be tracked with unified CX metrics that go beyond channel metrics. Fourth, in order to facilitate this process, there is a need for integrated systems. In this section, we discuss these enablers and support our analysis with quotes from the coding phase.

3.1.1. Strategic Customer-Centric Mindset at Scale

Strategic decisions have a high decisional weight in investment decision-making, even more than profitability [

21]. Strategy thus appears to be a fundamental enabler for omnichannel adoption as a business practice, as it is aligned with priorities and investments. A strategic investment is one that “contributes to create, maintain, or develop a sustainable competitive advantage” [

21]. As previously mentioned, in this hyperconnected era, being omnichannel creates a competitive advantage. Therefore, omnichannel experience management has to be a top-down priority, relying on the company’s core purpose for a long-term customer-centric strategy while delivering actionable short-term quick wins and continuous improvement. Being omnichannel is a construct resulting from a long-term step by step process built on business priorities:

“The idea of customer experience is already installed in the company’s vision. In fact, it says “experience” in a manager’s role name. There is a lot of focus, many things have been done (…) At least we’re already measuring [customer experience] and we’re worried about it”.

(P4)

This customer-centric mindset means omnichannel experience management needs to be a business strategy that adds value throughout the customer journey, even for those leads that do not convert into customers:

“The typical problem in sales is that we apply surveys to those who successfully completed the transaction, which does not reflect the reality of those that, perhaps, arrived at a branch store and left because it was crowded”.

(P6)

Even from a sales funnel perspective, those prospects that do not buy should have high-level experience with the brand, making them want to come back in the future as potential clients. This approach is coherent with being people-centric beyond sales. In this context, embracing CX at all levels also means better transitions from sales to aftersales. Throughout the customer journey and depending on the industry, transitions from sales to aftersales are managed differently. Based on the cases reported by the participants, in the banking industry, a client has the same assigned executive throughout their journey, while in telecommunication companies, there is a sales team dedicated to attracting customers and closing the sale, while another aftersales team continues to deliver timely support. Naturally, satisfaction with the sales process tends to be higher than satisfaction with customer support over time:

“The truth is that the sales satisfaction is one of the highest (…) so this is not something we are planning to improve”.

(P6)

3.1.2. Brand Customer-Centric Outcomes

In line with strategy, having brand customer-centered outcomes is a strong enabler to become omnichannel. Based on our managerial interviews and previous literature research [

8], organizations must design with a customer-brand relationship in mind, going beyond touchpoints or channel definitions. In order to do so, from a customer experience design perspective and a research methodology perspective, the customer journey is one of the most mentioned methods:

“Basically we do continuous improvement from the gaps that we detect in our processes, either by the design of the customer journey or by the issues that emerge from continuous monitoring or claims”.

(P2)

Nevertheless, for some of the interviewed managers, the customer journey is considered to be too simple and does not allow them to discover new actionable insights:

“When you get to detect something, I have already corrected it (…) if you find insights, it is most likely that since I have the daily report I have already corrected it in the week you took to analyze why it was a problem. I have never received an insight from the customer experience team that has told me “this should be implemented”.

(P6)

The perception that the customer journey is not as rich as it is expected to be in terms of insights highlights a lack of in-depth application of the method, even if this does not seem to be a generalized appreciation for the participants. As with any other customer research method, the customer journey has its strengths and weaknesses.

When asked about how they plan to evaluate CX in this new omnichannel context, practitioners mentioned the need to ensure brand satisfaction as a top priority and to understand critical moments that have a direct impact on this outcome. Consequently, integrated metrics would be needed as the actual experience evaluation—with specific metrics being measured per channel—does not reflect one consistent experience.

Furthermore, our findings for services are consistent with previous research on retail that states the need for managers to segment customers based on their use cases, as a complement to traditional segmentation based on socio-demographic characteristics [

22]. Therefore, the need for two types of solutions is identified. The first one is automation in order to track customer experience over time while it occurs. Automation would also allow one to ensure a bigger sample so the collected and analyzed data would be more representative than actual monitoring samples, which are considered to be small:

“Our monitoring samples are quite small because they are processed by humans, since what we do is random listening, so we have no capacity for more. Knowing that we have more than one and a half million calls per month, plus five hundred thousand visits, that is, two million … but we have very small samples”.

(P8)

A second expectation is to count on predictive methods, allowing them to anticipate gaps in the experience and take action before it is too late. As a current practice, most of the time, customer experience is evaluated right after a transaction occurs, or at a given time in the future (for example, at the end of the month, or end of the year).

3.1.3. Unified CX Metrics

After the organization designs and implements their CX strategy, it becomes necessary to measure and track the results. In practice, one of the most common standard metrics mentioned during the interviews is the Net Promoter Score (NPS). NPS is usually tracked per channel, per process, or even per product:

“We track the NPS per channel. In fact, if the broker is in charge of commercial and collective products, we see what they sell the most and evaluate that product. Because all the areas that are behind supporting the products are different. Then, finally, the experience (…) can be very different because they have different sales executives, different support areas, products developed differently, different contributors. So, it is measured by channel”.

(P5)

The NPS is mainly valued as a benchmark metric, allowing one to identify where a brand stands compared to its competitors:

“We have strongly adopted an indicator called NPS, which is well known worldwide and allows certain benchmarks”.

(P1)

Nevertheless, when the time comes to manage, meaning to take concrete actions based on the results of the eventual NPS reporting, this indicator fails at being actionable:

“Managing the NPS is supercomplex, it’s like a thermometer (…) The NPS is obviously correlated with satisfaction […]. But the NPS today is a number that tells us that we are improving, but if you ask me “Well, does what you do make the NPS go up?” I would be super-irresponsible if I say that I make the NPS go up. (…) The satisfaction is to comply, the NPS is the “wow” factor (…) I’m more of a (NPS) detractor than a fan. The NPS contributes to seeing the change in time, but I feel that the score … I feel that it is how the user felt at that time, I have seen how someone during a test has struggled with a task, but gave us a great score”.

(P3)

Even if NPS is not considered actionable enough, it is still the most common unified indicator that reflects the experience with the brand at some point. When looking at the NPS over time, an improvement in the metric does not necessarily come from a real improvement in CX, and it is highly related to human factors, such as the learning curve:

“It happened to me in a bank where we made a very drastic change (in the website) and we knew that people would not be happy, but it was what we had (…) Knowing that there is a learning curve, we applied the NPS shortly after having changed the interface to a group of users and, of course, the result was bad. We surveyed the same users a month later to find out how much of that had changed, once they got used to this new “reality”. Of course, we saw a change and people, in the end, adopt whatever is necessary, because there is no other choice, but if they give you a good mark afterward that does not mean it is okay”.

(P10)

Unified goals create a common goal for teams. Based on our analysis, we propose that another omnichannel enabler is having unified CX metrics, meaning these metrics are cross-channel- or channel-independent. These metrics do not replace channel metrics as these are still valuable for practical and operational purposes:

“I believe that soon we will all have a common vision and that the goals of all directors will be transversal to the bank (…) Because if we see it as silos, each one is going to watch over his ranch, and that is what is changing little by little (…) That is what still needs to be established: a goal for all, without differences, silos or barriers”.

(P9)

“(We track) first call resolution not per channel, but transversally. Now all the indicators that you surely know are being omnichannel”.

(P2)

3.1.4. Integrated Systems

A fundamental enabler for transitioning from a multichannel to an omnichannel approach is having integrated systems. As mentioned in the introduction, traditional organizations that were not born digital tend to have siloed systems, a factor that needs to be addressed early in the operationalization of the omnichannel strategy.

Integrated systems allow information transparency from both perspectives: for the customer and the company. First, the customer has access to consistent information about the company at different touchpoints. Second, the company (through their customer executives, for example) has access to consistent data about the clients. As long as a client interacts with the company, there is a tracking opportunity to capture objective data.

Even if the human factor and the business strategy are fundamental for achieving an omnichannel organization, CX needs to be built on an integrated system:

“There is a lack of systems allowing integration that is needed for a unified experience (…) Omnichannel still looks like something at a high level; many things have to be fixed before reaching that. So, what do you get with being omnichannel if your CRM is not so modern, it is rather siloed and monolithic? I feel that we have to continue advancing in other things before reaching omnichannel”.

(P4)

When looking at touchpoints that are digital, such as websites and social media, it would be expected that these channels are connected because they are both digital so there should exist a more natural connection between them. Nevertheless, usually social media accounts are managed by digital agencies or marketing departments. These providers are then disconnected from the other company’s channels, and this is reflected in the customer experience as there is no information transparency between touchpoints:

“Social networks are totally disconnected; the branch executive has no context of everything that has had customer support on Facebook or Twitter”.

(P6)

Even when organizations are engaged in a digital transformation process, social media tends to continue to be disconnected from the rest of the company’s channels:

“That has always been disconnected and with the digital transformation project this is still disconnected”.

(P11)

When the actual team workflow is analyzed, the silos continue to exist even in close-knit teams:

“So, for example, a bank is responsible for payment methods. There is this person in charge of the website, the one in charge of the applications, the one in charge of the branches, and they do not necessarily talk to each other. So, those people do not always have the same objectives as areas, but maybe the product manager invents a new form of payment for a specific product and asks for it to be developed without a previous conversation (with the others)”.

(P9)

From a pure IT perspective, this is a known challenge commonly associated with the classical waterfall model for software development. Even if the Chilean ecosystem has adopted agile and lean methodology for software development, and the companies where our participants work are more than familiar with these concepts as their organization is going agile, working in silos continues to be an important issue. Ultimately, this has consequences on the customer’s experience. Our findings are consistent with previous research that shows data management, and particularly data integration, is one of the key enablers in omnichannel CX management [

23].

3.1.5. Willingness to Invest

From a pure IT perspective, this is a known challenge commonly associated with the classical waterfall model for software development.

Finally, in order to leverage the previous enablers, managers—and especially C-level ones—must be willing to invest in omnichannel capabilities. Strategic decisions such as digitalization and digital transformation should be supported by willingness to invest. Our research shows that this is also an enabler for adopting an omnichannel approach to CX:

“The only thing that I would add […] is the willingness of companies to make the necessary technological investments to implement it (note: omnichannel capabilities)”.

(P1, Group interview)

Our findings suggest that investing in technology is, at first, an intuitive financial decision that managers can take in order to support their omnichannel approach. However, investment in information technology should come with new and stronger human talent and capabilities as well as cultural and organizational changes, as we will show in the next section.

3.2. Challenges

Previous business research tends to present several of these factors together, e.g., enablers and drivers [

24]; drivers, enablers, and barriers [

25,

26]; or drivers and barriers [

27,

28]. In our analysis, we stress that the barrier concept can be overwhelming from the participants’ perspective. This is why during the coding stage of the analysis, we merged a set of factors into a theme we called challenges. Consequently, human resources, organizational culture, and organizational behavior emerge as the main challenges that businesses encounter during their journey from multichannel to omnichannel CX.

3.2.1. Human Talent

A first challenging aspect of the transition towards an omnichannel CX management is the need for new organizational and cultural practices in order to support channel integration, redesign the way teams interact, and redesign the way common goals are defined and evaluated. Unquestionably, human talent must be approached as a main challenge throughout the transition process, thus avoiding reducing the change to a mere technological investment.

In this new context, human talent is key from multiple perspectives and at all levels in the organization. First, there is leadership: omnichannel strategy needs to be a priority defined from the strategic vision. Second, it is necessary to articulate the participation of each manager and those in charge of the channels since a drastic structural change is unlikely. There are several opposing forces relating to these roles. On one hand, managers understand the need to rethink the division of the channels and the concept of channel ownership. On the other hand, some team leaders, such as those in charge of digital teams, feel empowered and advocate that they should be leading the change. These findings are consistent with previous research in the context of the digital transformation towards omnichannel retailing in a German sportswear brand [

29]. In that case, the researchers found that digital teams speak both languages: the technology one and the business one.

Participants confirmed that the actual channel ownership does not reflect the customer’s reality but is rather a corporate convention. A product or channel-based structure comes with working in silos. A horizontal structure is even proposed at some point:

“How do I plan to structure it? Very flat and have a segment manager to deliver all this view of a single customer of the company”.

(P7)

Managers stress that working in silos is one of the negative consequences of channel ownership:

“For example, to sell a consumer credit or a checking account or whatever through the web, the closing process will most likely be physical. It won’t even occur at our office, it will be through an external delivery service or someone who is going to make sure you sign. So, connecting all those worlds, which are generally acting in silos, is what we are working on, rather than working on a tool that allows you to connect everything naturally and that is 100% digital”.

(P9)

For one of the participants, the same disconnection occurs between the web team and the customer experience department of the organization:

“I don’t know if what I have to say is politically correct but I do not work with the customer experience department, because they are more after-sales oriented. When we want to get into sales experience our dynamics is day by day: that is, I am seeing the numbers every day, how they can be improved, and increase the effectiveness of our tactics”.

(P6)

As per this participant, CX data are not seen as immediately informing the digital sales team as it does not feel the methods from the CX department are valid, nor do the data provide valuable insights to their team. In terms of organizational challenges, being peer validated is crucial to gain attention. At this level, some tensions arise. On one hand, this channel management practice (channel ownership) is perceived as inappropriate for the client experience and for teamwork as it puts a barrier between processes. On the other hand, the channel owner is believed to be the one that has more insights and is more empowered to drive changes:

“The truth is that the level of depth (understanding) that we have is difficult to get for someone who does not know anything about the world of sales, who came to do client research only once (…) It is very difficult for new ideas to emerge; ideas that have not occurred to us. In general, they can suggest things that seem obvious and the reason it has not been done is because it cannot be executed or the execution is long”.

(P6)

Becoming omnichannel requires the total commitment of the entire organization:

“So I think we need to address the process from people’s perspective. (…) I believe that behind a project there must be a cultural change that I do not know if it is being approached correctly. Because in the end we need to convince [top management] that this vision of being customer centered is the strategy that will give us results (…)”.

(P7)

“There is an additional work of culture, of change management and making sure that things happen”.

(P2)

Further research should be done to gain a deeper understanding of how teams working in the backend (e.g., IT, operations) or frontend areas (e.g., call center, sales, and aftersales executives) affect the customer experience. Teams working together on CX challenges often have different backgrounds, expectations, and daily responsibilities. Aligning teams around a common purpose will resonate and bring a sense of unity in this diversity.

3.2.2. Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is another internal strong factor that has an influence on any transition process from multichannel to omnichannel. To illustrate, some informants stress that working in a company managed by engineers introduces complexity to their daily challenges:

“What I do believe is that the big problem is complexity, that in the end we are a company of engineers and engineers are more complex than other professionals, so they lead us to a difficult to manage level of complexity. So, customer journeys are complex, processes are complex, systems are complex; at this point customer experience is already complex”.

(P4)

The interviewed digital team leaders feel their teams should be leading the change from a multichannel to an omnichannel customer experience approach, in the same way they feel they should lead the digital transformation process. Nevertheless, we argue that digital skills have to be adopted across the entire organization, starting with the C-level and the board. Additionally, diversity brings new and broader perspectives to teams.

3.2.3. Organizational Behavior

The way teams work—or the organizational behavior—is a strong challenge for any transformational process as it depends on the complex human behavior and cognition. Based on our analysis, it is difficult to design a new service without associating it with a channel. As a consequence of the channel ownership and management patterns that arise from this structure, one of the first things that teams start defining when designing a new service is in which channel to situate this service:

“Basically, it is difficult for people to understand that, especially for a service, there does not necessarily have to be a website, it does not necessarily have to be an app, or on a mobile and, at best, it does not have to be any digital channel because it makes no sense, because it is something that the user does not want to do there”.

(P10)

Therefore, it is difficult to say where a channel stops and, as we mentioned before, the channel concept belongs to the company, not to the customer:

“In terms of experience or satisfaction, the customer satisfaction index is omnichannel, because the client thinks about everything. (In the survey) We have a question about face-to-face experience, one about the call center, one about the login-based website and one about the public website. So, when the client thinks about their global experience, even if they think about each process, then we ask how satisfied they are with the company, and there they think about it as a whole. The client has always been omnichannel, we were not omnichannel, but for the client in the end, there is one experience (with the brand)”.

(P10)

3.3. Drivers

Drivers are often presented as factors opposed to barriers [

30] or as means to overcome barriers or even motivations to adopt a certain business practice [

31]. In our analysis, drivers are determining factors that lead an organization to approach omnichannel CX as a business practice. Drivers motivate change at a strategic level. Without the drivers, enablers are not enough to trigger the change—here the change is the transitioning process, but once a driver emerges, the organization has the intrinsic motivation to transition to omnichannel. Enablers become factors that facilitate this process. Without strong drivers, omnichannel is only nice to have but not essential.

Three high-level drivers emerged during the group sessions: the COVID-19, the need to acquire more clients, and the need to manage the after-sales customer relationships. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the transition from managing multiple channels in silos to better channel articulation mainly because the actual silo model was stressed by the high adoption of digital and remote channels by the customers and employees. These are actually macro trends or contextual factors that we will discuss further.

3.3.1. COVID-19

In this continuously changing environment, never before had an external factor had such an accelerating power as COVID-19 for both customers and businesses (“

we were highly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic”, P10, group interview). Contextual factors shape businesses at different levels. However, COVID-19 has not only been an external factor influencing managerial decisions but rather a strong driver that motivates transformational decisions. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a key external driver for digital transformation [

32] in general, not only for omnichannel adoption (“

the COVID-19 came to completely rock the boat”, P7, group interview).

Eventually, other external factors beyond COVID-19 will have an influence on this transition process. As we will discuss in the next section, contextual factors tend to have an impact on organizations. The difference between COVID-19 as a driver and the other contextual factors is that COVID-19 not only has an influence but is also motivated by and furthermore triggers several changes that lead to the acceleration of this transformation process. In order to take advantage of similar external factors in the future, organizations must use adversity as an impulse to generate a transformational opportunity. Otherwise, strong motivational factors will only have an impact as contextual factors, not drivers.

3.3.2. Client Acquisition

For many businesses, the need to orchestrate client acquisition while delivering a seamless experience for both potential customers and sales and marketing employees—as they need to deliver an optimal service—became one of the key internal drivers to adopt omnichannel capabilities:

“We made a change and we had to accelerate the digitization or remote sales that we did not have [before the COVID-19 pandemic]”.

(P2, Group interview)

This acceleration in the sales process was motivated by the previous reliance on traditional channels, which have now ceased to operate or continued to operate with many restrictions, especially during 2020. Organizations that take the need to better articulate client acquisition and turn it into a driver for omnichannel CX are those that stop managing sales in silos—meaning an independent stage of the customer journey—and rather see the complete picture of the customer journey.

3.3.3. After-Sales Customer Relationships

This acceleration in the sales process was motivated by the previous reliance on traditional channels, which have now ceased to operate or continued to operate with many restrictions, especially during 2020.

Organizations had to rethink their customer journeys and find better approaches to acquire, engage, convert, and retain customers through positive experiences with the brand. As one of the participants mentioned, if the pre-sale experience and sale experience tend to be positive by nature, the after-sales customer relationships require better articulation. In this context, after-sales customer relationships are a key internal driver that motivates businesses to adopt an omnichannel approach for their CX management:

“The trigger [for adopting omnichannel] was after-sales (…) Before [the COVID-19 pandemic] what happened-and that generated many complications for us-was that when a new client arrived the sales process was not unified with the post-sales process”.

(P5, Group interview)

“At a practical level, what it implied is that it forced the creation of a patient care area and a care model (…) defining the role of each channel (…) and the implementation of supporting technology”.

(P3, Group interview)

In order to address after-sales customer relationships as a driver in an omnichannel context, managers must think further than the purchase journey. Indeed, one strategy to approach CX management is looking for relevant experience moments in time and delivering lifetime value for customers. Moreover, practitioners must identify the “moments of truth” in the client lifecycle and design for that intended experience:

“(…) we were less transactional in the conversations and that added a very interesting level of sensitivity that gave us a lot of closeness with the clients”.

(P4, Group interview)

3.4. Context: Macro Trends Shaping the Competitive Landscape for Service-Based Companies

During the first phase of our study, we also explored contextual factors (

Figure 4) that influence not only organizational decisions but also managers and overall practitioners’ individual decisions. For instance, participants recalled services commoditization as a macro trend shaping the competitive landscape particularly for massive B2C services such as telecommunications, banking, and insurance:

“I think all telecommunications companies today are almost the same. Some can give you more gigabytes and others can be cheaper, but what can distinguish one company from another is how we approach and how we treat customers. (…) So, what you have to deal with is how to create loyalty so that your clients stay with you”.

(P5)

Given that it is increasingly difficult to differentiate a brand in terms of intrinsic characteristics of the service, the experience factor becomes a fundamental asset in the fast-changing digital age. In line with this, when asked about the local references, participants mention the banking industry as being the more mature one in terms of being able to offer a consistent customer experience through different channels and allowing customers to start a transaction in one channel and continue and finish it in a different one (“It is a much more mature market than ours, the banks have been here for over 200 years now”, P1). Subsequently, organizations not only need to adapt to industry changes, they also need to anticipate them.

In this context, the attention should be not only on differentiation from competitors but also on understanding the evolution of client’s expectations considering the context, i.e., the past experience with other brands and the mental references, as these mental references shape customer’s behavior.

4. Concluding Thoughts and Implications

Our study gives rise to a range of opportunities for different stakeholders—both researchers and practitioners—involved in customer experience. As a theoretical contribution, the proposed framework posits that enablers are not enough to trigger the adoption of omnichannel CX capabilities at scale. Drivers, such as COVID-19, client acquisition articulation, and after-sales customer relationships, are strong factors triggering the transition process. Additionally, these components of the framework and the factors we identified do not live separately. Indeed, in a complex system, different internal and external factors can be enhanced for an organization when encountered together.

There are multiple managerial implications when applying this framework to the transition process from a multichannel to an omnichannel approach to CX. First of all, for senior management, if omnichannel was a strategic issue in their organization, there might be time to rethink the classical channel management approach in order to redesign the channel ownership. In order for their organization to get to an omnichannel customer experience, their actual structure should be customer-driven, not channel-driven. Moreover, people interact with a brand, not with specific channels. In this context, the focus should be on the CX with the brand throughout the customer journey, beyond a channel. Second, for medium-level managers in organizations that were not born digital, there is the need for digital skills allowing one to empower their teams throughout the process of designing an omnichannel company. Otherwise, internal conflicts might be generated by the natural tendency digital teams have to lead continuous change. Finally, for C-level and top management, an omnichannel strategy should be aligned with the company’s purpose by making omnichannel CX a top-down priority.

As per the metrics for omnichannel customer experience, if, on one hand, integrated metrics are needed in order to measure customer experience and, on the other hand, channel ownership is redesigned or totally discarded, then these metrics should not be measured by channel but rather by critical moments from the customer journey or as high-level metrics reflecting brand experience. Even if it is not actionable, NPS is still a high-level relevant metric for brand experience, allowing team alignment and benchmarking.

Finally, for both practitioners and researchers dedicated to customer experience, our work suggests potential opportunities in customer experience evaluation methods and tools that need to be explored, as well as integrated metrics. First, we stress (1) the need to examine field research approaches to ensure consistent experience evaluation along the customer journey based on the identified critical moments (moments of truth) and (2) the opportunity to get back to the basis in order to design an intended brand experience that goes beyond a specific channel or touchpoint.

Beyond CX strategies, we recommend to involve human resources management in this transitioning process. We would like to acknowledge our study limitations. First, due to time and resources constraints, we had to limit the industries represented in this research. Namely, our participants came from financial services, airlines, telecommunications, and the education industry. However, consultancy professionals bring a general vision of the transition process from multichannel to omnichannel as they have access to a broader project portfolio as they work with different clients in several industries. Although we conducted our research until data saturation was reached, the number of participants was small, so generalizability is not expected—rather, we aim to provide an understanding of the issues raised by our participants. Second, our research is focused on CX aspects of omnichannel approach. As expected, the findings mainly reflect the context of service companies. For example, if we had done a similar study in retail, logistics and reverse logistics would probably have gained an important relevance. Finally, in order to convey the user’s perspective through this framework and ensure it is customer-driven, we expect future research to address several gaps. As an insight from the human–computer interaction perspective, as we saw during this study, practitioners wish for management practices that are customer-based and not company-based, which leads us, for example, to question the channel ownership model. In a similar way, we, as researchers, should consider the person as a whole, throughout their journey and beyond a device. This could be reflected in simple actions such as referring to a “person” or “human” more than a “user”.

Future research should also include an omnichannel customer experience management maturity level, allowing managers to apply a self-assessment methodology in order to identify gaps that should be addressed in order to properly transition from multichannel to omnichannel CX management. Moreover, organizational aspects of this transition process should be addressed in future research with a focus on human capabilities, organizational structure, and organizational change management. Additionally, a case study approach could be used to validate the framework in different industries and countries.

5. Ethical Considerations

The research protocol was approved by the university ethics committee (protocol number: 170918001). Respondents received information about the research project and were informed that their participation was voluntary, that anonymity would be granted, and they could withdraw from the study at any time. Before the interview, informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G.; methodology, C.G.; formal analysis, C.G.; investigation, C.G.; resources, C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.; writing—review and editing, C.G. and V.H.; visualization, C.G.; supervision, V.H.; project administration, C.G.; funding acquisition, V.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONICYT/FONDECYT, grant number 1211210 (Chile).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Pontifícia Universidad Católica de Chile, protocol code 170918001, approved on 27 March 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent Statement was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Guide (Phase #1)

Introduction: Give a presentation, outline the research, sign the informed-consent form, and obtain consent for audio recording.

Background and context

Customer experience design and evaluation

Omnichannel customer experience (CX)

How do you approach omnichannel in this context?

Would you say your organization is multichannel or rather omnichannel?

If they respond multichannel or in transition: what is it missing for your organization to be omnichannel?

Suppose that tomorrow you are omnichannel, how is this CX different?

Note: At this point, participants mentioned their organization is not omnichannel yet. Therefore, we used probing to go deeper into what is omnichannel CX for them and how their organization is getting to reach this stage.

Which methods do you use to evaluate the CX in this context?

Which (evaluation) instruments do you use?

Which performance indicators do you use?

What do you positively notice in this process?

From your perspective, what is missing from the current evaluation process?

How do you do continuous improvement based on this input (note: the CX evaluation)?

Suppose you are omnichannel: how would you evaluate CX in an omnichannel context?

Are there any organizations you consider to be a reference in terms of omnichannel CX? Any industry?

Appendix B. Group Interviews Guide (Phase #2)

Introduction: Give a presentation, outline the research, read the informed-consent form, and obtain consent for video recording.

Background and context:

Participant’s introduction: role within the firm, background, and experience;

Research introduction: a brief presentation of the findings of study #1.

Non-structured conversation based on the findings

At this stage, participants were spontaneously invited to discuss findings, sharing their own perspective and experience.

Moderated discussion of the transition process:

What impact did COVID have on this process in your company?

From the academia perspective, how could we help you facilitate this process?

Do you have any experience with maturity models?

References

- Verhoef, P.C.; Kannan, P.K.; Inman, J.J. From Multi-Channel Retailing to Omni-Channel Retailing. Introduction to the Special Issue on Multi-Channel Retailing. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q. Conceptualization of omnichannel customer experience and its impact on shopping intention: A mixed-method approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. Impact of COVID-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, C.; Bourlakis, M.; Hüber, A.; Wollenburg, J.; Holzapfel, A. Retail logistics in the transition from multi-channel to omni-channel. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 562–583. [Google Scholar]

- Thaichon, P.; Phau, I.; Weaven, S. Moving from multi-channel to Omni-channel retailing: Special issue introduction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 65, 102311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A.; Kuhn, H.; Wollenburg, J. Last mile fulfilment and distribution in omni-channel grocery retailing. A strategic planning framework. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2014, 44, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barann, B.; Hermann, A.; Heuchert, M.; Becker, J. Can’t touch this? Conceptualizing the customer touchpoint in the context of omni-channel retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 65, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieva, M.; Ziliani, C. Mapping touchpoint exposure in retailing: Implications for developing an omnichannel customer experience. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltola, S.; Vinio, H.; Nieminen, M. Key factors in developing omnichannel customer experience with finnish retailers. In HCI in Business; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 335–346. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, A.; Olarte-Pascual, C.; Juaneda Ayensa, E.; Murrillo, Y.S. The role of technology in an omnichannel physical store. Assessing the moderating effect of gender. Span. J. Mark. 2017, 22, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Neslin, S.A. The omnichannel continuum: Integrating online and offline channels along the customer journey. J. Retail. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparin, I.; Panina, E.; Becker, L.; Yrjölä, M.; Jaakkola, E.; Pizzutti, C. Challenging the “integration imperative”: A customer perspective on omnichannel journeys. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.Y.; Li, J. Seamless experience in the context of omnichannel shopping: Scale development and empirical validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerea, C.; Gonzalez-Lopez, F.; Herskovic, V. Omnichannel Customer Experience and Management: An Integrative Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, I.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Montoya, M. Preparing for Interview Research: The Interview Protocol Refinement Framework. The Qual. Rep. 2016, 1, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boddy, C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. 2016, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. In Qualitative Research in Psychology; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2006; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Cooremans, C. Make it strategic! Financial investment logic is not enough. Energy Effic. 2011, 4, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parise, S.; Guinan, P.J.; Kafka, R. Solving the crisis of immediacy: How digital technology can transform the customer experience. Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnein, M.; Heuchert, M.; Homann, L.; Trautmann, H.; Vossen, G.; Becker, J.; Kraume, K. Towards Efficient and Informative Omni-Channel Customer Relationship Management. In Proceedings of the ER 2017 Workshops, Valencia, Spain, 6–9 November 2017; LNCS 10651. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sancha, C.; Longoni, A.; Giménez, C. Sustainable supplier development practices: Drivers and enablers in a global context. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 21, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.A.; Deschamps, F.; da Silva, E.R.; de Lima, E.P. Digital twins in manufacturing: An assessment of drivers, enablers and barriers to implementation. Procedia CIRP 2020, 93, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Hamilton, M.; Fabian, K. Entrepreneurial drivers, barriers and enablers of computing students: Gendered perspectives from an Australian and UK university. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 1892–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, A.; Cagno, E.; Trianni, A. Barriers and drivers for the adoption of industrial sustainability measures in European SMEs: Empirical evidence from chemical and metalworking sectors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 1433–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegger, A.S.; Klein, J.F.; Merfeld, K.; Henkel, S. Technology-enabled personalization in retail stores: Understanding drivers and barriers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.; Sia, S.K. Hummel’s Digital Transformation Toward Omnichannel Retailing: Key Lessons Learned. MIS Q. Exec. 2015, 14, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Thollander, P.; Ottosson, M. An energy efficient Swedish pulp and paper industry—Exploring barriers to and driving forces for cost-effective energy efficiency investments. Energy Effic. 2008, 1, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cagno, E.; Trianni, A.; Spallina, G.; Marchesani, F. Drivers for energy efficiency and their effect on barriers: Empirical evidence from Italian manufacturing enterprises. Energy Effic. 2017, 10, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauser, S. COVID-19 as a Driver for Digital Transformation in Healthcare. In Digitalization in Healthcare: Future of Business and Finance; Glauner, P., Plugmann, P., Lerzynski, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).