Abstract

Given the increasing competition and the impact of digital media in the automobile industry, dealerships need to understand the antecedents of customer happiness and brand love. The goals of the study are to analyse the combined influence of the cognitive and affective drivers of brand love for high-involvement products and its effects on behavioural intentions, paying special attention to the moderating role of susceptibility to information posted on social media. Using a sample of 317 Jordanian car buyers, a structural model is tested that confirms that the sales consultant’s empathy is a strong predictor of customer happiness during a car purchase and a stronger predictor of his/her trust in the car dealership. Happiness and trust translate into greater brand love, which in turn can generate resistance towards negative information posted on social media; positive electronic word-of-mouth; and willingness to pay more. Happiness fully mediated the relationship between empathy and car brand love. The effect of the impact of the perceived empathy of salespeople on customer happiness was stronger for consumers with low susceptibility to information posted on social media. This work expands the academic knowledge of the direct mediating and moderating effects of brand love.

1. Introduction

The automotive market is characterised by very intense interbrand competition [1]. In a business environment, driven by digitalisation, competition and the transition to green mobility, car dealers try hard to make their customers happy. Car dealerships seek to make their customers happy because this provides key financial benefits: greater customer lifetime value; repeat business, such as second car purchases; service appointments; upselling opportunities; and positive word-of-mouth (WOM) recommendations to friends and family [2,3]. While companies in the sector are customer centric, ref [4]’s metanalysis showed that the consumer journey has not received the attention it deserves in the marketing literature. These authors argued that how companies can generate happiness among their customers is a research gap that should be addressed.

Customers experience various feelings when interacting with company employees. For example, they might experience positive emotions when the salesperson at a car dealership is friendly and empathic. Customers’ interactions with frontline car dealership employees are crucial in shaping their perceptions of dealerships. Indeed, these interactions may influence their decision to choose and recommend dealerships [5,6,7]. However, few works examining the role of frontline employees in customer–company relationships have assessed the emotions aroused when customers interact with sales consultants [4]. Previous studies have failed to examine these interactions from the cognitive appraisal perspective [8] or explain how the consultant’s empathy might enhance the consumer–brand relationship in general or with car brands in particular. Addressing these issues can help car dealerships understand better how to train their employees to make their customers happy. Drawing on cognitive appraisal theory (CAT), it is proposed that customers’ perceptions of the empathy exhibited by consultants during interpersonal service interactions can elicit a strong positive emotional response (happiness).

Consumers frequently report intense emotional relationships with brands, comparable to feelings of interpersonal love [9]. Given the increasing competition in the automobile industry, it is important to understand the antecedents of brand love, as this love has considerable influence on customers’ behavioural decision-making processes [10,11]. Brand love is recognised as being a critical success factor in the retail industry as it fosters strong customer loyalty, advocacy and positive brand perceptions [12,13]. Due to brand love’s managerial importance and theoretical interest, many studies have investigated its antecedents [14]. However, limited academic research has taken place into the combined influence of the cognitive and affective drivers of the construct and its consequences for these relationships [15]. The present study investigates whether cognitive beliefs such as the trust elicited by the consumer’s evaluation of the car dealership, two-way customer–company communications and customer happiness can trigger a passionate feeling towards a brand.

Studies that have analysed the links between brand love and consumers’ emotions have reported mixed results. Some studies have argued that brand love has an indirect effect on consumers’ well-being [16] and on other positive emotions [17]. However, evidence has also been presented that the customer’s happiness with service facilities is key to increasing his/her brand love [3]. A happy customer may evaluate everything around him/her positively and this positive thinking/mood may favourably impact future purchase decisions. The present study contributes to previous research about the links between brand love and consumers’ emotions by proposing that customer happiness has a direct effect on brand love for high-involvement products.

Recent research has examined the effects of the empathy shown by frontline employees on customer–employee trust [18]; however, the effects of this empathy on the trust the consumer holds in retailers are under-researched [19]. The present study goes beyond previous works by proposing, based on trust transfer theory [20], that the customer’s perceptions of the empathy of frontline service employees have a direct impact on his/her trust in the retailer.

Researchers have expressed conflicting views about the relationship between trust and brand love. Albert et al. [21] concluded that brand love evokes brand trust. Salehzadeh [22] argued that brand love is a necessary precursor of brand trust. In addition, previous research has examined the relationships between brand love and trust [23,24,25] but did not assess the process of how brand love develops from perceived trust. The present study expands knowledge of the trust–brand love relationship by proposing that a transfer effect takes place from the trust the client feels for a car dealership to brand love for the car brands marketed by the dealership.

Online reviews have been shown to be important sources of information for consumers purchasing high-involvement products [26]. Recent literature has called for research to be undertaken into whether the consumer’s susceptibility to online sources of information impacts his/her behaviours [26,27]. Most research into the effect of online reviews on product sales has focused on low-involvement products; research into brand love and behavioural intentions for high-involvement products is scarce. Offline and online information are alternative information sources that shoppers use as bases for their brand choices in retail establishments but few studies have compared the effects of offline sources (sales consultants) and online sources (online reviews) on consumers’ purchase decisions. The present study analyses two effects. First, the direct impact of social influence on brand love and, second, the moderating effect of the consumer’s susceptibility to information (online reviews) on the impact of the empathy of the sales consultant on the trust and happiness evoked during a high-involvement product purchase experience. Understanding whether consumers’ happiness with and trust in retailers of high-involvement products differ based on their susceptibility to information posted on social media can help these retailers develop better online marketing tactics.

The automobile industry was chosen as the context of this research because it is a growing sector that has faced significant challenges during the years 2020 to 2023. Understanding the dynamics of brand love can provide useful insights for the producers and consumers of the automobile industry. The industry has been impacted by rising interest rates, tighter credit conditions and geopolitical fragmentation, which has reshaped regional value chains [28]. The COVID-19 pandemic forced the automobile industry to accelerate its digital transformation, enhance operational resilience and adapt to rapidly changing market conditions characterised by decreasing demand [29]. In 2022, global vehicle production increased by 5.7%, reaching 85.4 million units, driven by the rise of electric vehicles (EVs) [30]. The automobile market is expected to experience substantial growth, particularly in emerging markets, with Asia being the world’s leading vehicle producer and consumer [31]. In comparison to other Asian nations, such as China and Japan, Jordan’s automobile market is small but is one of the most rapidly expanding in the continent [32]. The country’s automotive industry is underpinned by several factors, including the availability of skilled labour, research and development initiatives, government backing and geographical advantages. With a favourable economic forecast and increased household purchasing power, the nation is poised to experience a substantial swell in automobile sales by the year 2030.

Inspired by the great economic importance of the automobile industry, its increasing competition and because brand love is a vital part of its marketing efforts [33], this study investigates the dynamics of brand love (its antecedents and effects). A research model is tested that investigates the effects of the consumer’s cognitive perceptions about the car dealership, social influence and the happiness (s)he feels during the purchase experience on brand love. Special attention is paid to the moderating effect of the specific personality trait of susceptibility to the influence of social media. The model is based on the stimuli–organism–response (SOR) framework [34], which has been applied in many contexts.

This study makes the following contributions to the literature:

- While there is a growing understanding of consumer brand love, there is a lack of consensus regarding the direct effects of the consumer’s cognitive perceptions of communications controlled by the company (two-way communications and perceived empathy with the salesperson) and social influence (subjective norms) on brand love. Similarly, little attention has been paid to the mediating roles of the customer’s happiness, and the trust (s)he feels towards the retailer, on these relationships.

- This work expands the knowledge, in the context of the automobile industry, of the effects of brand love on three crucial customer behavioural intentions: willingness to pay more; positive electronic word of mouth (eWOM); and resistance to negative information posted on social media.

- While studies have examined the direct effects of interpersonal service interactions on the customer’s emotions and on customer trust, little research has taken place into the moderating effects of individual characteristics on these relationships [35]. The present work analyses the moderating role of the consumer’s susceptibility to online influences, one of the most important antecedents of purchase behaviours.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows. First, we conduct an in-depth review of the literature related to the study’s variables and formulate working hypotheses. Second, we explain our data collection and measurement validation processes. Next, we discuss the main findings, conclusions, managerial implications and limitations of the work. Last, we outline some possible avenues for further research.

2. Literature Review

This study uses a new lens to examine brand love, that is, the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) framework [34]. The SOR framework was originally developed in the environmental psychology domain [34]. The SOR framework proposes that stimuli perceived in the environment impact the individual’s cognition, emotions and behaviours [36]. The underlying mechanism of the SOR paradigm is that external stimuli influence the individual’s emotions and cognitive processes, which in turn shape his/her responses [37]. Stimuli (S) encompass both internal and external surroundings and act as drivers of individuals’ internal emotional states; organisms (O) are the perceptions evoked in the individual by the internal and external stimuli encountered in retail settings, just before (s)he makes a purchase; and responses (R) are the individual’s reactions to the perceived stimuli [38].

The SOR framework is applicable to this research for three reasons. First, the SOR model is well accepted and has been used by researchers examining consumer behaviours in several contexts. Examples are retail buying [39], travel-focused artificial intelligence [40] and hospitality services [41]. Second, the SOR theory’s practicability and rationality were proved in recent research that extended it to explain purchase intentions for electric vehicles [42,43,44] and autonomous vehicles [45]. Hu et al. [44] adopted the SOR model to explore the effects of information overload on consumers’ psychological states and subsequent adoption intentions for EVs. Xu et al. [43] extended the SOR theory to show that consumers’ car driving experiences (stimulus) affected their purchase intentions for cars (response) through car (organism) evoked emotions and cognition. Dzandu et al. [45] applied the SOR model to explain autonomous vehicle adoption in the UK. Upadhyay and Kamble [42] used the SOR model to examine the antecedents of Indian consumers’ proenvironment vehicle purchases. Third, the SOR framework provides a concise and structured way of examining the impact of external stimuli (e.g., the empathy of a consultant) on consumers’ psychological perceptions and subsequent behaviours.

3. Proposed Model and Hypothesis Formulation

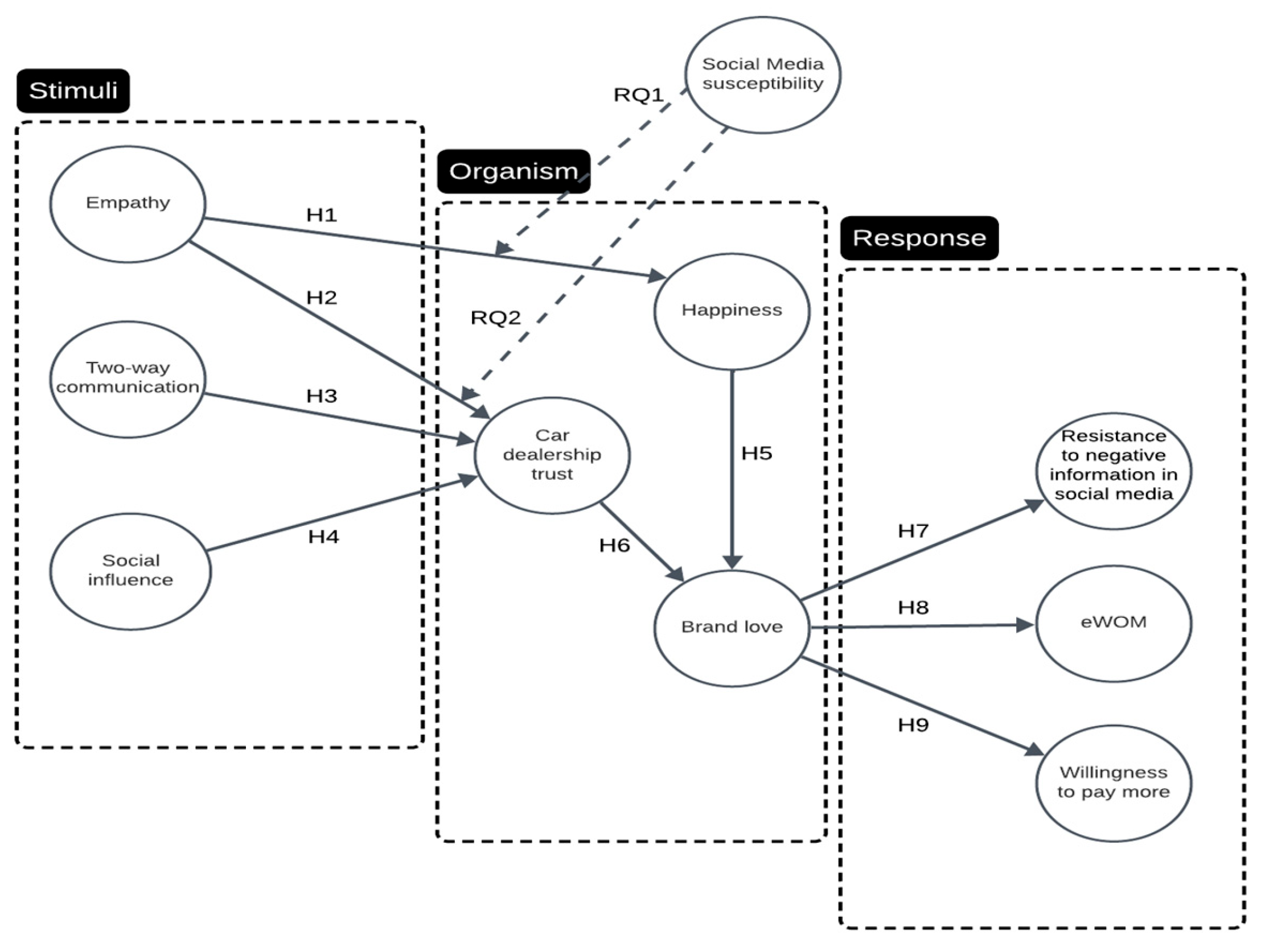

This study proposes that two-way communications, interpersonal service interactions and subjective norms (stimuli) activate trust and brand love (organism), which subsequently elicit willingness to pay more, positive eWOM and resistance towards negative information (responses). The mediating roles of happiness and trust and the moderating effect of the consumer’s susceptibility to information posted on social media are also analysed. Figure 1 depicts the research model.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.1. Stimulus

3.1.1. Perceived Empathy, Customer Happiness and Trust

Sales personnel are a primary source of the customer’s service experience. Customers care about how they are treated in their interactions with sales consultants and frequently experience emotions based on these interactions [46,47]. The recent meta-analysis of [4] conceptualised happiness as a momentary positive emotion experienced by consumers, elicited by encounters with marketing stimuli before, during and after consumption. The present study focuses on the customer happiness elicited during the purchasing process.

Empathy is the ability to understand what other people think and feel [48]. The effect of empathy on emotions can be explained by cognitive appraisal theory, CAT [49]. CAT proposes that during customer–salesperson interactions, customers appraise overall service, behaviours (actions) and attributes and then compare these appraisals with their own standards. The assessment creates an emotional response. When customers interact with empathic sales consultants, their appraisals may be that the sales consultants are customer oriented, which they will likely view as desirable [50]. Therefore, empathetic helping (a service skill) may influence the customer’s happiness [51]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The customer’s perceptions of the automobile sales consultant’s empathy with him/her positively influence his/her happiness.

In the field of relationship marketing, there is general agreement that trust is the belief held by one party (the consumer) in the integrity and good faith of the other party in the exchange (the company) [52]. The trust that a consumer has in his/her car dealership is based on cognition and/or affect [53]. That is, the consumer can develop trust based on his/her perceptions of the competence, credibility and reliability of the car dealership (cognitive-based trust) and, on the other hand, based on the friendliness, pleasantness and likability (affect-based trust) of the dealer. Consequently, frontline service employees need to adopt empathic behaviours in face-to-face interactions; this can play a significant role in developing a good-quality company–customer relationship [54].

Social exchange theory [55] proposes that trust is more likely to develop when a social exchange occurs. For example, if employees take good care of customers, this care benefits both the firm and the employees. The parties voluntarily participate in the social exchange, with the expectation of receiving personal benefits that they would not be able to obtain individually [56]. Customers expect empathic behaviours from service employees during their interactions [57]. Retailers who employ salespeople who pay attention, listen to their customers’ problems and understand what they want are seen to be making efforts to provide high-quality service; this leads their customers to trust them [18]. Lee et al. [58] described trust transfer as a process in which a person (customer) bases his/her initial trust in an entity (retailer) on the trust (s)he holds in some other related entity or person (frontline employees). Trust transfer theory, thus, proposes that the consumer’s cognitive trust, generated by his/her perceptions of the empathy displayed by the sales consultant, can be transferred to cognitive trust in the car dealership [59].

Hence, we posit that the customer’s perceptions of the empathy of the sales consultant have a positive effect on his/her trust in the car dealership.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The customer’s perceptions of the automobile sales consultant’s empathy with him/her positively influence his/her trust in the dealership.

3.1.2. Two-Way Communications

Customer-brand relationships are based on emotional bonds. Two-way communications are the interactive dialogue between a company and its customers; these take place during the preselling, selling, consumption and postconsumption stages [60]. The trust that consumers feel towards their favourite car dealership is based on whether they perceive it to be honest, benevolent and competent. The two-way communications that take place between the car dealership and its customers link them with the car brands sold by the car retailer. Accordingly, from the consumer’s perspective, the association between the car dealership and its car brands lays a foundation for the trust transfer process to take place [20]. When customers, for instance, want to absorb brand information sent by the retailer, endorse the brand and share information about the brand, this is a sign that they trust the retailer [61]. Therefore, we posit that the two-way communications that take place between the car dealership and its customers transfer trust to the car dealership.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The two-way communications that take place between the car dealership and its customers have a positive effect on the customers’ trust in the car dealership.

3.1.3. Social Influence

Social influence is based on the individual’s perception that others important to him/her think (s)he should or should not perform a specific behaviour [62]. Individuals feel social pressure, that is, the need for social approval, when engaging in specific behaviours (e.g., choosing a car dealership) [63]. What other people do motivates individuals to follow the same behaviours. In this regard, [64] emphasised the importance of the individual’s subjective norms in the acceptance of autonomous driving vehicles because people tend to follow what other people do and think.

In line with social impact theory [65], which argues that social influences impact consumers’ emotions and behaviours, we propose that social influence increases trust in car dealerships because consumers rely on information received from others important to them [66,67]. The effect of social influence on the purchase-decision-making of car brands has been proven in many studies; this underlines the importance of other people’s opinions when individuals make purchase decisions about high-involvement products, such as automobiles [68]. Following this reasoning, we argue that social influences impact the trust customers place in a car dealership.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Social influence has a positive effect on the trust that consumers place in a car dealership.

3.2. Organism

Affective Factors: Positive Emotions and Brand Love

Brand love is a customer’s passionate emotional attachment to a brand, which is characterised by passion, intimacy and commitment [69]. Passion is the enthusiasm that stems from the consumer’s motivational involvement with the brand; intimacy is his/her emotional willingness to remain connected to the brand; and commitment relates to his/her short- and long-term decisions to love and commit to the brand. These authors suggested that brand love has five distinct characteristics: passion for the brand, connection with the brand, positive evaluation of the brand, positive emotions felt towards the brand and (explicit) declarations of love for the brand.

Customer happiness and brand love are not the same thing. The key differences between brand love and customer happiness lie in their nature and focus. Brand love reflects a deep emotional commitment to a specific brand, akin to interpersonal love; it is characterised by intense feelings, deep affection and separation distress. It involves a strong emotional attachment to a brand that goes beyond mere satisfaction and/or loyalty [9]. Brand love has been described as being an integral part of the use of a product or service [3]. While brand love is specific to one’s emotional connection with a brand, customer happiness is a more general emotional state that encompasses overall well-being and positive feelings [4]. In essence, brand love is a targeted emotional attachment to a brand, while customer happiness is an emotional experience that reflects overall contentment and positivity.

Brand love has been said to pertain to affection and be the cause of prolonged purchase interactions [70]. Customers are likely to evaluate brands favourably when they cause them to experience positive emotions [71]. Based on CAT [49], we argue that customer happiness arises through an appraisal process that can positively influence one’s overall judgment of a brand; thus, consumers who feel happy with their car-purchasing experience at a car dealership will be more likely to develop brand love towards the car brand. Hence, we propose that:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Customer happiness evoked by the car-purchasing experience at the dealership increases brand love for the car brands sold by the dealership.

CAT proposes that an individual’s cognition (trust in a car dealership) influences his/her affective states (brand love) and subsequent behaviours [72]. Trust is commonly associated with the loving feelings shared by partners [73] and has been empirically associated with love and intimacy. In the context of the present study, CAT explains how brand trust transits to brand love. Accordingly, strong trust in a brand has been associated with desirable outcomes, such as positive attitudes and loyalty, which have been shown to be important antecedents of brand love [74].

Based on CAT, we propose in the present study that brand trust is a cognitive factor that creates brand love; recent research has provided evidence for this contention. Gültekin and Kilic [75] argued that when consumers trust brands, they develop emotional attachments to them. Vacas de Carvalho et al. [76] demonstrated the existence of a mediating effect of automobile brand affect on the influence of brand trust on consumers’ resistance to negative information. Therefore, we argue that brand love stems from brand trust.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Trust in the car dealership influences car brand love.

3.3. Response

3.3.1. Attitudinal Responses: Resistance to Negative Information Posted in Social Media

Recent research has posited that customers with a strong emotional attachment to a brand are less likely to be affected by negative information about the brand than are customers not similarly attached [70,76,77]. Evidence also exists that customers with a high level of brand love are more likely to adopt a positive frame of reference when processing negative information about the brand [78]. In addition, studies have shown that brand love can mitigate the negative effects of brand failure [66,79]. Homburg et al. [80] showed that consumers in love with a brand resist negative information about, and forgive, the brand. Thus, we posit that consumers with a strong emotional connection to a car brand are more likely to maintain positive attitudes towards and beliefs about the brand, which can mitigate the effects of negative reviews/comments posted on social media about the brand.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Car brand love positively influences resistance to negative information posted on social media about the car brand.

3.3.2. Behavioural Responses: Positive eWOM and Willingness to Pay More

By demonstrating affection for a particular brand, the consumer communicates his/her feelings about the brand. Previous studies have shown that brand love prompts consumers to post positive communications about the brand on digital media [11,13]. Positive associations between brand engagement and eWOM have been shown to exist [13]. However, most of these studies were conducted in a non-Asian geographic context and there have been frequent calls for further examination of this relationship in different contexts [11].

Therefore, we posit that when consumers love car brands, they become emotionally connected to the associated car dealership; they passionately wish to keep interacting with the dealership and its communities; they advocate for the dealership; and they post positive reviews about it.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Car brand love influences consumers to engage in positive eWOM about the car dealership.

3.3.3. Brand Love and Willingness to Pay More

Willingness to pay a premium price is, according to [81], “the highest price level at which the consumer is willing to pay for the goods or services”. Homburg et al. [80] found that consumers with a deep emotional connection to a brand were willing to pay a premium for its products, even when those offered by competitors were comparable. Bairrada et al. [82] found that consumers with a deep emotional attachment to a brand were willing to spend up to 30% more on a company’s products than were those without such a connection. Consumers who are deeply emotionally attached to a brand feel that it is irreplaceable; thus, they are willing to pay more for the brand [83]. Therefore, we posit that car dealerships that create and reinforce brand love are likely to see a positive impact on customers’ willingness to pay more for their cars.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Car brand love influences willingness to pay more.

3.4. Moderating Effect of the Consumer’s Susceptibility to Social Media Information

Consumers conduct extensive information searches when they purchase high-involvement products. Online reviews continue to grow as primary sources of online information and interaction for consumers and play an important role in their purchasing decisions. Customers consult online reviews to reduce uncertainty and to avoid financial losses [26].

Consumers do not immediately make their purchase decisions after obtaining information about high-involvement products, rather they repeatedly confirm the authenticity and reliability of the information through various sources. Fernandes et al. [27] asserted that consumers with a high susceptibility to online information make their product purchases based on various forms of online sources of information, for example, company-related information and product ratings on websites and blogs. Consumers also corroborate the evidence they gather by evaluating the quality of the reviews they consult, thus reducing the uncertainty they face in relation to product quality.

With the growing use of online information sources, building interpersonal relationships with customers becomes more difficult, even for companies selling high-involvement products, as the quantity and frequency of employee–customer contacts may be diminishing. This raises research questions as to whether customers with different susceptibilities to information posted on social media respond differently to the empathy shown by salespeople.

Research Question 1 (RQ1).

Does the customer’s susceptibility to online reviews have a moderating effect on the relationship between the perceived empathy of the sales consultant and his/her happiness?

Research Question 2 (RQ2).

Does the customer’s susceptibility to online reviews have a moderating effect on the relationship between the perceived empathy of the sales consultant and the customer’s trust in the car dealership?

4. Methodology

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

This empirical study took place March–October 2023 in collaboration with Abu Khader Automotive (AK), the leading automobile dealership in Jordan. Questionnaires were distributed to a population of 1300 buyers who purchased Cadillacs, GMCs, Chevrolets or Opels from AK in the years 2020–2023. This study was based on data obtained from an online questionnaire [84].

The population was identified using AK’s customer relationship management platform. While data gathered based on a single case have limitations in terms of the generalisation of results, this approach allowed us to conduct a very detailed analysis [85]. We followed previous brand research studies that used a single case as a research context. Ref. [86] measured active and passive participation in the Zara brand Facebook community; Royo and Casamassima [85] used a themed attraction restaurant to analyse experience value creation; Murillo et al. [87] used a Veepee company to analyse eWOM behaviours in the branded mobile apps of fashion retailers; and Ballester et al. [41] used an eco-friendly restaurant to identify the effects of brand engagement on customer advocacy and behavioural intentions. We used a nonprobabilistic convenience sampling procedure. The customers were sent, via WhatsApp, a URL that they could visit over a one-month period. The questionnaire was developed in English and then translated into Arabic. To prevent nonresponse bias, we assured the respondents that the study was anonymous and two reminders were sent to the target population [88]. We obtained 317 valid responses.

The majority of respondents were male (73.8%). The largest proportion were in the 25–54 age range (59.9%), followed by 55–64 (18.6%), 18–24 (13.6%) and those aged 65 and over (7.9%). The majority were married (70%). Some, 43.5%, were employed, 26.5% self-employed, 13.9% retired, 11.7% unemployed and 4.4% were students. The highest percentage of respondents reported having no children (37.2%), followed by four (14.2%), two (14.8%), three (13.9%), five or more (10.4%) and one (9.5%). The highest concentration lived in Amman (77.0%), followed by Irbid (6.6%), Zarqaa (3.8%), Balqa (2.2%) and elsewhere (less than 2%). The majority of respondents had bought new vehicles, constituting 78.7% of the sample, while 21.3% had bought used vehicles. Chevrolet was the most favoured brand, with 51.7% of the preferences, followed by Cadillac (18.9%), Opel (18.5%) and GMC (15.4%). The sample is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample description.

4.2. Measurement Instrument

We measured the study constructs using multi-item scales, mostly five-point Likert-type scales, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Happiness was measured on a single-item scale, adapted from [89], that asked respondents how happy they felt after their purchasing experience at the car dealership. Car brand love was measured using a five-item scale adapted from [69]. The respondents’ self-reported trust was measured using a three-item scale adapted from [90]. Two-way communications were measured by adapting the scale of [60]. Willingness to pay more was measured using a three-item scale adapted from [33]. Intention to spread positive eWOM was measured using a two-item scale adapted from [17]. Resistance to negative information was measured using a three-item scale adapted from [91]. Empathy was measured using a four-item scale adapted from [18]. Social influence was measured using a three-item scale adapted from [92]. Social media susceptibility was measured using a three-item scale adapted from [27]. The constructs and scales are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Scales used in the study.

5. Results

We chose PLS-SEM (partial least squares-structural equation modelling) as the estimation method due to the complexity of the model, which involves numerous constructs, indicators and relationships [93]. The parameter estimation was carried out using Smart-PLS 4.0 [94] and we performed bootstrapping with 10,000 samples to determine the significance of the parameters (see Table 3). The composite reliability of the constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.60 [95]. In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs surpassed the 0.50 threshold [96]. As an indicator of convergent validity, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) demonstrated that all items were significantly related (p < 0.01) to their respective factors [97]. Table 3 displays the mean factor loadings for all the dimensions, each of which exceeds the criteria for convergent validity.

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity of the measurement instrument.

The measurement model’s ability to discriminate between constructs was verified using the [97] criterion, the square roots of the AVEs exceeding the interconstruct correlations (see Table 4, values below the diagonal). In addition, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio values (Table 4, above the diagonal) support the conclusion that the measurement model possesses discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity of the measurement model.

In the next step, we checked for the presence of nonresponse bias. To assess nonresponse bias, [98] applied a time-trend prediction method, which involves comparing early and late responders. They proposed that late responders would share similar characteristics with nonresponders. Following [98]’s procedure, we divided the study participants into two groups, one made up of those who responded before the first reminder (within 15 days) and one made up of those who responded after the first reminder. Some 161 respondents (50.7%) were classified as early responders, while the remaining 151 (49.3%) were classified as late responders. To assess the potential for nonresponse bias, an independent sample t-test was conducted for each construct (EMP, TWC, SI, HAP, TRU, LOV, RESI, eWOM and WTP). The results in Table 5 indicate that there are no statistically significant differences between the two groups, suggesting that the study is not influenced by nonresponse bias.

Table 5.

Assessment of nonresponse bias.

Finally, common method bias (CMB) may arise in this type of research design [99,100]. We took proactive measures to address CMB concerns, such as ensuring the participants of the anonymity and confidentiality of the study, emphasising that there were no right or wrong answers and encouraging them to respond with honesty. Furthermore, we meticulously examined the questionnaire items to eliminate ambiguous, vague and/or unfamiliar terms. In addition, following the recommendations of [101], we tested for the existence of CMB by employing a single questionnaire and maintaining consistent scale formats across all variables. The results of a Harman’s single factor test also alleviated CMB concerns, revealing that one factor accounted for 48% of the variance, below the 50% threshold [100].

In addition, we took the full collinearity assessment approach proposed by [102] to test for CMB in PLS-SEM. This approach proposes that a variation inflation factor (VIF) greater than 3.3 is an indication of pathological collinearity and that the model is contaminated by CMB. Table 6 presents the VIFs of the inner model, all below the 3.3 threshold; it can, therefore, be concluded that the model has no CMB problems. Table 6 also reports the outcomes of the hypotheses testing and displays the standardised coefficients for the structural relationships and the corresponding significance levels of the t statistics.

Table 6.

Test of the hypotheses.

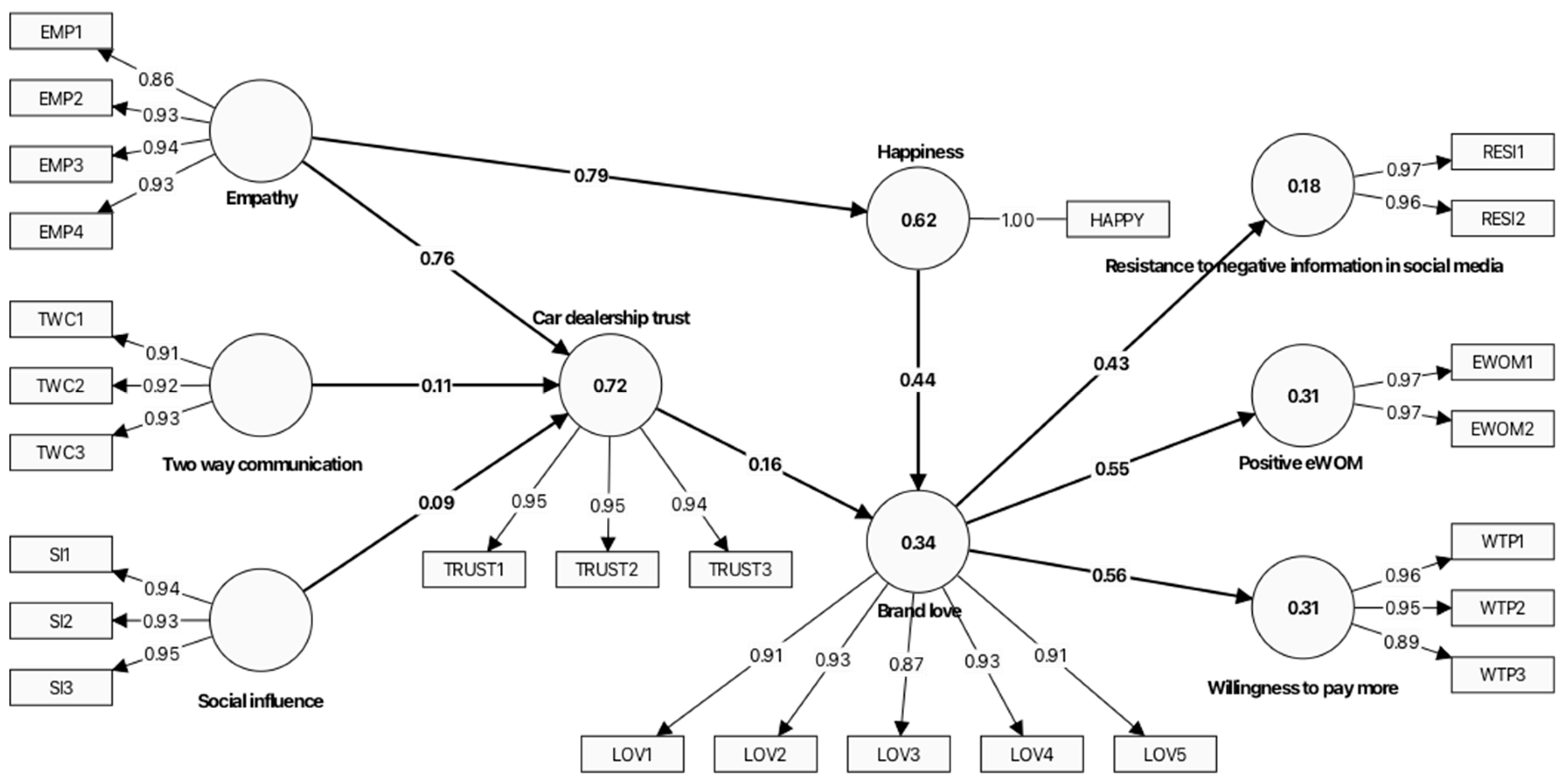

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the model’s estimation in SmartPLS 4.0.

Figure 2.

Estimated model.

The model estimation confirmed that the consultant’s empathy is a powerful predictor of the happiness experienced by customers during a car purchase (β = 0.79, H1 accepted) and their trust in the car dealership (β = 0.76, H2 accepted). Two-way communications (β = 0.11, H3 accepted) and social influence (β = 0.09, H4 accepted) also improve trust in the car dealership but with much less intensity than the empathy of the consultant. Interestingly, the two emotional responses towards the car dealership analysed in the model were shown as capable of being transferred into greater car brand love for the manufacturer (happiness: β = 0.44, H5 accepted; trust: β = 0.17, H6 accepted). Finally, it was shown that car brand love is a significant antecedent of the three behavioural responses analysed: it generated resistance towards negative information posted on social networks (β = 0.43: H7 accepted), positive eWOM (β = 0.56: H8 accepted) and willingness to pay more (β = 0. 57: H9 accepted). The estimation had R2 and Q2 values that met the minimum established criteria; thus, the structural model shows predictive relevance.

To complement the analysis, we estimated a new model to identify if the stimuli (i.e., empathy, two-way communications and social influence) had any direct effects on car brand love. Table 7 shows the results of this analysis. As can be seen, happiness fully mediated the relationship between empathy and car brand love and partially mediated the effects of two-way communications on brand love; however, car dealership trust was not a significant mediator between the stimuli variables and car brand love.

Table 7.

Mediation analysis.

Finally, we tested the moderator role of social media susceptibility (i.e., SM SUSC) on the effects of empathy on happiness (RQ1) and car dealership trust (RQ2). To do this, we first calculated a global index of SM SUSC (α = 0.90) for each participant and then split the sample into two groups using the median (Mdn = 3.5) of SM SUSC as the dividing line. This division produced a group of consumers with high (n = 185; M = 4.26) and low (n = 132; M = 2.48) social media susceptibility; the groups were seen to have significant differences (t = 26.41; p < 0.01). As our goal was to analyse any differences between the two groups in specific path coefficients of the model (and not in the global model), we ran the nonparametric permutation-based test (NPT) [103] using SmartPLS 4.0. The results are shown in Table 8. As can be observed, the positive effect of empathy on happiness is reinforced when social media susceptibility is low. Thus, consumers who rely less on the company’s social media to obtain information about car brands are more likely to be made happy by the empathy shown by employees. However, this moderating effect does not take place in the influence of empathy on car dealership trust.

Table 8.

Moderation analysis of social media susceptibility.

6. Discussion

The present study showed that the customer’s perceptions of the empathy of salespeople, a dimension of service quality, played a pivotal role in the formation of trust in the car dealership, and in the happiness elicited during the purchase. This result supports previous research that showed that personalised attention [71,104,105] and the behaviours of company personnel [3,106,107] are important antecedents of the creation of positive emotions felt towards retailers.

The research also adds new insights to CAT that help explain the underlying mechanisms of the transition of brand trust to brand love. Consistent with CAT, it was found that cognitive components are antecedents of emotions, which eventually lead to actions [53]. CAT has been applied successfully in several contexts [108]; the present study is relevant both for the automobile industry and for other high-involvement products. Loved brands have several advantages over trusted brands; for instance, enhanced (consumer) resistance to negative information posted on social media and (consumer) willingness to pay a higher price. However, brand trust is also an important precursor of brand love. Thus, marketers, to enjoy sustained competitive advantage, should focus on both.

The results showed that brand love enhanced consumers’ positive behavioural intentions towards brands (willingness to pay more, positive eWOM and resistance to negative information). In other words, consumers act in line with their feelings towards brands. The effects found in the study about brand love’s impact on resistance to negative information are in line with other recent research [76]. Consumers’ love for car brands causes them to resist negative information. When car dealerships encounter problems (e.g., changed customer expectations that affect perceived service quality, a reputation for charging high prices for spare parts, unfriendly staff) they may be faced with situations where consumers post negative information on social media. However, emotional factors were seen to affect consumers’ reactions towards unfavourable information about the car dealership. For example, when consumers have highly emotional relationships with brands, they are resistant to negative information about them [91]. Similarly, our findings are aligned with [109], who showed that brand love is a mediator between brand trust and resistance to negative information. Thus, positive brand affect can increase consumers’ willingness to pay more and their tendency to post positive eWOM and their resistance to negative information.

7. Conclusions

The main conclusions of this research are that brand love and customer happiness depend on, at least, three different stimuli: (1) communications controlled by the company (e.g., perceived empathy of the sales consultant and two-way communications); (2) social influence; and (3) a personal characteristic of the customer, that is, how (s)he processes information posted on social media—is it relevant, or not, for his/her purchase decision (consumer susceptibility to social media information)?

This work contributes to the emerging literature as, hitherto, most studies have investigated the impact of online reviews on consumers’ purchasing decisions for low-involvement products [26]. The nature of high-involvement products means that examining the role of the consumer’s susceptibility to information posted on social media in his/her purchase decisions presents different challenges to those faced by examinations into low-involvement products; information about these differences can offer retailers new insights to help boost high-involvement product sales.

Understanding how retailers increase brand love during the customer journey is an important research challenge, particularly in light of the increasing number of touchpoints that may divert customers along their journeys. The customer journey with a car dealership can be conceptualised in three stages [110]: prepurchase (the customer’s interaction with the car dealership before the purchase transaction); purchase (the customer’s interaction with the car dealership during the purchase process) and postpurchase (the customer’s interactions with the dealership following the purchase). To sustain competitive advantage, car dealerships should increase brand love by making customers happy throughout their customer journeys.

8. Implications

8.1. Theoretical Implications

This work extends knowledge about customer–brand relationships and provides additional support for the applicability of the SOR paradigm [34] to high-involvement products (automobiles) through an analysis of the dynamics of brand love for high-involvement products. It also adds to previous research by testing a novel model that assesses the impact of three antecedents of brand love: (i) the direct effects of the cognitive and emotional antecedents of brand love; (ii) the mediating effects of trust and positive emotions (happiness); and (iii) the moderating effects of one of the consumer’s personal characteristics (susceptibility to social media information). Understanding the effects of the cognitive and affective antecedents of brand love and how these antecedents relate to willingness to pay more, positive eWOM and resistance to negative information will help automobile retailers gain competitive advantage and respond to consumers’ demands.

Recent emotions-focused literature has explained how they enhance brand love [4]. Customer happiness fully mediated the effects of the empathy of frontline employees on brand love and partially mediated the effects between empathy and trust held in the retailer. These results are strong indications that it was the right decision to include customer happiness in the research model. In the extant, high-involvement product literature, the mediating effects of emotions on brand love are under-researched, despite this playing a significant role in the health of businesses, especially in the automotive industry.

Another theoretical contribution, consistent with CAT, is our demonstration that the perceived empathy of frontline employees impacts consumers’ overall evaluations of the specific service encounter (customer happiness) and positively influences the affection they feel towards the company, which develops trust in the company. The positive effect of perceived empathy on trust represents a transfer effect from customers’ perceptions of the service provided by frontline employees to their views about the dealership. The consumers’ perceptions of the empathy of employees benefited the retailer by improving their perceptions of its honesty, benevolence and competence.

8.2. Managerial Implications

The insights provided by this study allow us to draw practical conclusions for automobile retailers. Car dealerships must initiate the customer journey effectively, with particular emphasis being put on cultivating brand awareness. This prepurchase stage is pivotal for capturing the customer’s attention and fostering favourable perceptions. Customer relationship management (CRM) systems can help identify the customer’s preferences, purchase histories and interactions. This information can help sales consultants tailor their approaches, making each customer interaction more personalised. The findings also underlined the crucial roles of two-way communications and social influence as antecedents of car dealership trust. Both variables are pivotal during the prepurchase stage of the customer journey as individuals form their opinions, choices and behaviours through social influence, which significantly impacts their level of trust in the dealership. To address this, automobile retailers should consistently provide information on promotions and encourage feedback. Two-way communications should be sincere, honest and focused on building trust with current and future customers. Car dealerships should conduct advertising campaigns aimed at creating awareness among customers that their prices are fair, that they provide convenient services (long opening hours, accessible locations) and that their service centres have staff with the highest technical expertise.

The study also identified several empathy-related traits that sales consultants in automobile retail should exhibit during the purchase stage of the customer journey. The consultants should pay individual attention to customers, engage with them in a caring manner, listen to their problems and understand their needs. These traits were identified as crucial antecedents of increasing consumers’ perceptions of trust in the dealership and of their happiness. Therefore, automobile retailers should allocate resources to improve their perceived service quality by, first, hiring service personnel who exhibit empathy and, second, providing training programmes and performance evaluations for current personnel focusing on these traits.

Susceptibility to social media information about car brands can negatively moderate the effect of the salesperson’s empathy on happiness. When customers do not find the information posted on social media to be helpful during the prepurchase stage of the customer journey, they turn to alternative channels in the next stage. It is crucial that sales consultants establish empathy with their customers during all stages of the customer journey. This can foster interpersonal connections that enable the sales personnel to obtain the information they need to make the customer happy. To address this challenge, automobile retailers should provide sales consultants with relevant information. This will empower them to engage in personalised interactions and understand customers’ specific needs and preferences. A customer-centric approach is essential; it should extend beyond the transaction and be a genuine connection. As customer happiness is elicited through activities that take place during all the stages of the customer journey [4], it is important that sales consultants build relationships with customers outside of transactional interactions.

Customers value ongoing communication with dealerships during the postpurchase stage. Consequently, automobile retailers should address these aspects, perhaps by implementing reward strategies for customers who refer others to their dealership. These customers, thus, can act as advocates for the dealership, influencing others to make purchases. In addition, the postpurchase stage is crucial for establishing long-term relationships with customers. Hence, car dealerships should maintain consistent, long-term communications with their customers. This will foster enduring connections and enhance the customers’ perceptions of the honesty, competence and benevolence of the retailer.

Brand love acts as a powerful buffer against negative sentiments expressed on social media, providing a layer of protection for the brand’s reputation during all stages of the customer journey. When customers feel a strong emotional bond with an automotive brand, they are more inclined to actively share positive experiences, reviews and recommendations on their online networks. Automobile industry managers should cultivate brand love among their existing customer bases by providing personalised experiences and exceptional customer service in each stage of the customer journey. Brand love can be enhanced by establishing rewards/loyalty programmes for those customers who actively advocate car dealership brands (by spreading positive eWOM) and by hosting events exclusively for these customers. These gatherings express the dealership’s gratitude to the customers for their continued support and loyalty and can be used to collect feedback during the postpurchase stage of the customer journey with an eye to cultivating a community of enthusiastic brand ambassadors. A personal touch, for example, sending birthday wishes to their customers, would generate in them a feel-good factor and encourage them to engage in positive eWOM.

9. Limitations and Future Research Lines

The study has limitations that open promising avenues for future research. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study provides only a snapshot of the hypothesised paths; a longitudinal design could be used to identify time-based facets and provide more rigorous empirical support for the hypotheses. Second, car brand love is strongly influenced by cultural factors; thus, understanding cultural differences is crucial for the automotive industry [111]. Multicultural marketing is an important element of automotive sales. Understanding the individual consumer and meeting his/her needs is part of cultural intelligence gathering, whether dealing with customers who are Hispanic, Asian, mature or millennial. Sachs [112] showed that consumers’ perceptions of heritage brands in the automotive industry are shaped by cultural factors. Gopinath and Narayanamurthy [113] assessed the moderating effect of culture on the impact of perceived ease of use on attitude, perceived usefulness and behavioural intentions to adopt autonomous vehicles. Thus, we propose testing our model using a sample of Western customers to assess whether the drivers and outcomes of brand love differ based on culture. Third, we are keenly aware that focusing on a single company and product type (new cars) limits the generalisability of the results; hence, it would be worthwhile to test the model with a sample of second-hand cars. Examining brand-specific outcomes might provide interesting information about the distinctive qualities that cultivate brand love. Therefore, we propose comparing our results with the perceptions customers have of Chinese car brands to increase the generalisability of the results. Finally, the present research is limited by the constructs examined. We propose, as a future research line, analysing the moderating effects of consumers’ personality traits and demographic variables on the impact of customer trust on brand love.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.R. and R.C.-P.; methodology, M.H. and R.C.-P.; software, R.C.-P.; formal analysis, R.C.-P. and M.H.; writing—original draft, M.H.; supervision, C.R. and R.C.-P.; funding acquisition, C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (ID grant number: PID2019-111195RB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 0).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy restrictions. The database contains information about customers of AK Automotive.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical support given by AK Automotive in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hamzah, M.I.; Pontes, N. What drives car buyers to accept a rejuvenated brand? The mediating effects of value and pricing in a consumer-brand relationship. J. Strateg. Mark. 2024, 32, 114–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dhiman, N.; Yousaf, A.; Arora, N. Social comparison and continuance intention of smart fitness wearables: An extended expectation confirmation theory perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 1341–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Analysing the drivers of customer happiness at authorized workshops and improving retention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, N.; Kumar, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Consumer Happiness: Three-Decade Review, Synthesis, and Research Propositions. J. Interact. Mark. 2023, 58, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Singh, A.K.; Kaushik, K. Evaluating service quality in automobile maintenance and repair industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.; Geetha, A. Factors Influencing Service Quality of Automotive Spare Parts in Chennai District. J. Res. Adm. 2023, 5, 435–450. [Google Scholar]

- Zygiaris, S.; Hameed, Z.; Ayidh Alsubaie, M.; Ur Rehman, S. Service quality and customer satisfaction in the post pandemic world: A study of Saudi auto care industry. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 842141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L. How to make users fall in love with a mobile application: A moderated-mediation analysis of perceived value and (brand) love. Inf. Technol. People 2024, 37, 1360–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Langner, T.; Temme, D. Brand love: Conceptual and empirical investigation of a holistic causal model. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 609–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Guzmán, F. Perceived injustice and brand love: The effectiveness of sympathetic vs empathetic responses to address consumer complaints of unjust specific service encounters. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruthi, M.; Kaur, H.; Islam, J.U.; Rasool, A.; Thomas, G. Engaging consumers via online brand communities to achieve brand love and positive recommendations. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2023, 27, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggara, A.K.D.; Ratnasari, R.T.; Osman, I. How store attribute affects customer experience, brand love and brand loyalty. J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 2980–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z.; Connolly, R. Commentary on Progressing Understanding of Online Customer Engagement: Recent Trends and Challenges. J. Internet Commer. 2021, 20, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuvia, A. The Things We Love: How Our Passions Connect Us and Make Us Who We Are; Hachette UK: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, N.; Khalil, S.H.; Ishaque, A.; Khalil, S.M. Lovemarks and beyond: Examining the link between lovemarks and brand loyalty through customer advocacy in the automobile industry. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaid, M.; Hussain, K.; Basit, A.; Hou, F. Nature of brand love: Examining its variable effect on engagement and well-being. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Andreu, L.; Perez, C.; Ruiz, C. Brand love is all around: Loyalty behaviour, active and passive social media users. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1613–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, W.; Khan, A.N.; Ali, A.; Usman, M. Investigating the effect of employee empathy on service loyalty: The mediating role of trust in and satisfaction with a service employee. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2020, 19, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, B.; St-Onge, S.; Ali, M. Frontline employees’ performance in the financial services industry: The significance of trust, empathy and consumer orientation. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 41, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.D.; Huang, J.S.; Su, S. The effects of trust on consumers’ continuous purchase intentions in C2C social commerce: A trust transfer perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The feeling of love toward a brand: Concept and measurement. Adv. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Salehzadeh, R.; Sayedan, M.; Mirmehdi, S.M.; Heidari, P. Elucidating green branding among Muslim consumers: The nexus of green brand love, image, trust and attitude. J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 250–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; Torres, P.; Augusto, M.; Stefuryn, M. Do brand relationships on social media motivate young consumers’ value co-creation and willingness to pay? The role of brand love. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, J.; Han, H. Effect of image, satisfaction, trust, love, and respect on loyalty formation for name-brand coffee shops. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumparthi, V.P.; Patra, S. The phenomenon of brand love: A systematic literature review. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2020, 19, 93–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, G. Online reviews and high-involvement product sales: Evidence from offline sales in the Chinese automobile industry. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 57, 101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.; Venkatesh, V.G.; Panda, R.; Shi, Y. Measurement of factors influencing online shopper buying decisions: A scale development and validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECB Economic Bulletin. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/economic-bulletin/focus/2022/html/ecb.ebbox202207_02~5bde8eeff0.en.html (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Statista. Topic: Automotive Industry Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/1487/automotive-industry/ (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- ACEA—European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/figure/motor-vehicle-production-by-world-region/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Coface, Automotive: Sector Risk Analysis and Economic Outlook. Available online: https://www.coface.com/news-economy-and-insights/business-risk-dashboard/sector-risk-files/automotive (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Research and Markets. Jordan Automotive Market: Size, Share, Outlook. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5713278/jordan-automotive-market-size-share-outlook (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Dwivedi, A.; Nayeem, T.; Murshed, F. Brand experience and consumers’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) a price premium: Mediating role of brand credibility and perceived uniqueness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Understanding the intention to follow the advice obtained in an online travel community. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, R. Chatbots in e-commerce: The effect of chatbot language style on customers’ continuance usage intention and attitude toward brand. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, P.; Liang, C. How does anthropomorphism improve human-AI interaction satisfaction: A dual-path model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D. Cultural values and energy-saving attitude-intention-behavior linkages among urban residents: A serial multiple mediation analysis based on stimulus-organism-response model. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023, 34, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.S.; Hampson, D.P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Consumer confidence and green purchase intention: An application of the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.C.; Duong, C.D.; Nguyen, G.K.H. What drives tourists’ continuance intention to use ChatGPT for travel services? A stimulus-organism-response perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, E.; Ruiz-Mafé, C.; Rubio, N. Females’ customer engagement with eco-friendly restaurants in Instagram: The role of past visits. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 2267–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N.; Kamble, A. Examining Indian consumer pro-environment purchase intention of electric vehicles: Perspective of stimulus-organism-response. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 189, 122344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Moving towards sustainable purchase behavior: Examining the determinants of consumers’ intentions to adopt electric vehicles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 22535–22546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, R.; Tong, Y.; Xu, L. Unpacking the effects of information overload on the purchase intention of electric vehicles. J. Consum. Behav. 2023, 22, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzandu, M.; Pathak, B.; Gulliver, S. Stimulus-Organism-Response model for understanding autonomous vehicle adoption in the UK. In Proceedings of the BAM2020 Conference in the Cloud, Virtual, 2–4 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Machleit, K.A.; Eroglu, S.A. Describing and measuring emotional response to shopping experience. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, K.; Dubé, L. Ensuring greater satisfaction by engineering salesperson response to customer emotions. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H.; Mitchell, K.V.; Hall, J.A.; Lothert, J.; Snapp, T.; Meyer, M. Empathy, expectations, and situational preferences: Personality influences on the decision to participate in volunteer helping behaviors. J. Personal. 1999, 67, 469–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, D.E.; Mangus, S.M.; Folse, J.A. The road to customer loyalty paved with service customization. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3923–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kim, H.; Vohs, K.D. Stereotype threat in the marketplace: Consumer anxiety and purchase intentions. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmat, G. A framework for transitioning brand trust to brand love. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 1554–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, O.S.; Inyang, A.E. The effects of empathy and listening of salespeople on relationship quality in the retail banking industry: The moderating role of felt stress. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 692–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tonder, E.; Saunders, S.G.; Lisita, I.T.; de Beer, L.T. The importance of customer citizenship behaviour in the modern retail environment: Introducing and testing a social exchange model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellesson, M.; Salomonson, N. The expected retail customer: Value co-creator, co-producer or disturbance? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, S.H. The impact of a mega event on visitors’ attitude toward hosting destination: Using trust transfer theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Ding, G.; Mo, J. Elucidating trust-building sources in social shopping: A consumer cognitive and emotional trust perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ner, A.; Putterman, L.; Ren, T. Lavish returns on cheap talk: Two-way communication in trust games. J. Socio-Econ. 2011, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarella, C.; Wagner, T.; Scheiner, C.; Maier, L.; Voigt, K. Investigating consumer acceptance of autonomous technologies: The case of self-driving automobiles. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 24, 1210–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B. The psychology of social impact. Am. Psychol. 1981, 36, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tao, D.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, H. Automated vehicle acceptance in China: Social influence and initial trust are key determinants. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 112, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. Antecedents of the adoption of the new mobile payment systems: The moderating effect of age. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, I.; Dimitrakopoulos, G. An empirical investigation on consumers’ intentions towards autonomous driving. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 95, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Mundel, J. Effects of brand feedback to negative eWOM on brand love/hate: An expectancy violation approach. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022, 31, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yi, Y. The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in five Asian countries. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Mathews, A. Cognitive processes in anxiety. Adv. Behav. Res. Ther. 1983, 5, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.; Merunka, D. The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüsken, K.; Henkel, S. What’s next on brand management? The Impact of Brand Authenticity on Brand Love. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual RESER Conference, Naples, Italy, 8–10 September 2016; pp. 1327–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Orzan, G.; Platon, O.E.; Stefănescu, C.D.; Orzan, M. Conceptual model regarding the influency of social media marketing communication on brand trust, brand affect and brand loyalty. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2016, 1, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Gültekin, B.; Kilic, S.I. Repurchasing an Environmental Related Crisis Experienced Automobile Brand: An Examination in the Context of Environmental Consciousness, Brand Trust, Brand Affect, and Resistance to Negative Information. Sosyoekonomi 2022, 30, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacas de Carvalho, L.; Azar, S.L.; Machado, J.C. Bridging the gap between brand gender and brand loyalty on social media: Exploring the mediating effects. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 1125–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q.M.; Raziq, M.M.; Ahmed, S. The role of social media marketing and brand consciousness in building brand loyalty. GMJACS 2018, 8, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, E.; Guzmán, F. No matter what you do, I still love you: An examination of consumer reaction to brand transgressions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand love. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. Do satisfied customers really pay more? A study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and willingness to pay. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C. The impacts of brand experiences on brand loyalty: Mediators of brand love and trust. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairrada, C.M.; Coelho, A.; Lizanets, V. The impact of brand personality on consumer behavior: The role of brand love. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, F.; Fuglsang, L.; Sundbo, J.; Jensen, J.F. Tourism practices and experience value creation: The case of a themed attraction restaurant. Tour. Stud. 2020, 20, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo-Vela, M.; Casamassima, P. The influence of belonging to virtual brand communities on consumers’ affective commitment, satisfaction and word-of-mouth advertising: The ZARA case. Online Inf. Rev. 2011, 35, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Zegarra, M.; Ruiz-Mafe, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. The effects of mobile advertising alerts and perceived value on continuance intention for branded mobile apps. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M.; Roycroft, J.; Amaya, A.; Dever, J.A.; Srivastav, A. The effectiveness of incentives on completion rates, data quality, and nonresponse bias in a probability-based internet panel survey. Field Methods 2020, 32, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.A. Measures of emotion. In The Measurement of Emotions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 83–111. [Google Scholar]

- Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M.; Gurrea, R. The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Thomas, A.; Veloutsou, C. Beyond technology acceptance: Brand relationships and online brand experience. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisingerich, A.B.; Rubera, G.; Seifert, M.; Bhardwaj, G. Doing good and doing better despite negative information?: The role of corporate social responsibility in consumer resistance to negative information. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.; Page, M.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of Business Research Methods; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Sinkovics, N.; Sinkovics, R.R. A perspective on using partial least squares structural equation modelling in data articles. Data Brief 2023, 48, 109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Meseguer-Artola, A. How to prevent, detect and control common method variance in electronic commerce research. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.H.; Thurasamy, R.; Memon, M.A.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H. Multigroup analysis using SmartPLS: Step-by-step guidelines for business research. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2020, 10, I–XIX. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R. The Big Five, happiness, and shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.J.; Chiou, S.C. Dimensions of customer value for the development of digital customization in the clothing industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, L.; Keiningham, T.L.; Buoye, A.; Lariviere, B.; Williams, L.; Wilson, I. Does loyalty span domains? Examining the relationship between consumer loyalty, other loyalties and happiness. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2464–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Hsee, C.K. Consumer happiness derived from inherent preferences versus learned preferences. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Back, K.J. Influence of brand relationship on customer attitude toward integrated resort brands: A cognitive, affective, and conative perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, M.U.; Gultekin, B. The critical role of brand love in clothing brands. J. Bus. Econ. Financ. 2015, 4, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding Customer Experience Throughout the Customer Journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.M.; Pires, C.P. Family firms and product recalls: An event study for the US automobile industry. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2024, 14, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, W. For Love of the Automobile: Looking back into the History of Our Desires; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath, K.; Narayanamurthy, G. Early bird catches the worm! Meta-analysis of autonomous vehicles adoption–Moderating role of automation level, ownership and culture. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).