Abstract

As augmented reality (AR) technology becomes more prevalent in marketing, its impact on consumer memory processes, particularly brand recall, remains underexplored. This study primarily employs an empirical research method, using two lab experiments to examine the interaction between product presentation formats (AR vs. non-AR) and presentation strategies (separate vs. collocation) in brand recall. Across two experiments, we showed that AR enhances brand recall only in collocation presentations, where multiple products are displayed together, but not in separate presentations of individual products. In single-product contexts, AR formats do not demonstrate a significant advantage over non-AR formats. These findings suggest that AR’s effectiveness is contingent on presentation strategy, highlighting the contextual boundaries of AR’s utility in influencing consumer memory. By integrating embodied cognition theory with associative network theory, this research advances our understanding of how immersive technologies shape brand recall, offering strategic insights for marketers seeking to leverage AR in diverse product presentation scenarios.

1. Introduction

AR technology is increasingly becoming a pivotal tool for enhancing consumer experiences in e-commerce [1]. Imagine a scenario where, instead of browsing static images of products, you can virtually place a piece of furniture in your living room, view it from various angles, change its colors, and observe how it fits within your physical space. This immersive experience can transform the way consumers interact with products online, providing deeper engagement and influencing their subsequent brand recall.

AR technology is gaining widespread adoption across various industries, injecting new vitality into marketing and retail, while also expanding the consumer media experience [2]. By overlaying digital content onto the real world in real time, AR provides an immersive and interactive experience that significantly enhances the consumer journey [3,4]. AR’s unique characteristic of environmental embedding allows consumers to interact with products in the context of their physical environment, as if they are already using the product [5]. This ability to simulate real-world scenarios has made AR a valuable tool in sectors ranging from cosmetics to home furnishings. For example, Sephora’s Virtual Artist app allows users to try on makeup virtually [6], while IKEA’s AR app helps customers visualize furniture in their homes [7].

In academic research, AR has been recognized for its ability to enhance consumer engagement and purchase intentions [8]. Studies show that AR can increase immersion, interactivity, and even the attractiveness of products, which, in turn, can drive higher purchase intentions and boost sales [9,10,11]. However, most research has focused on the later stages of the consumer journey—such as purchase intentions and product evaluations—rather than the earlier stages, where brand building and brand recall play crucial roles [12]. Research has demonstrated that a strong brand image is essential for enhancing brand recognition, trust, and customer loyalty [13]. A lack of brand recall can prevent consumers from even considering a brand during the decision-making process [14], which highlights the importance of investigating the effects of AR on brand recall in the earlier stages of the customer journey.

Despite AR’s growing popularity in marketing, its impact on brand recall has received relatively little attention. Brand recall refers to the strength of a brand’s association in consumers’ minds, which is essential for brand equity and long-term success [15]. Given the unique immersive and interactive qualities of AR, it has the potential to significantly enhance brand recall by embedding the brand within the consumer’s physical environment. However, previous studies have largely focused on how AR influences consumer brand attitudes and shopping behaviors [16,17], with few investigating the specific impact of AR on memory-based outcomes such as brand recall.

This study seeks to address this gap by examining the effects of AR on consumer brand recall in online shopping contexts. Specifically, we explore how different product presentation formats (AR vs. non-AR) and product presentation strategies (separate product presentation vs. product collocation presentation) interact to influence brand recall. Drawing on embodied cognition theory, which posits that physical interactions with the environment enhance cognitive processes and memory [18,19], we hypothesize that AR’s ability to simulate real-world interactions will enhance brand recall. However, the effectiveness of AR may vary depending on how products are presented.

In this study, we report the findings from two controlled lab experiments designed to empirically test our hypotheses. By employing both tablet-based non-immersive AR and head-mounted immersive AR, we explore the differential effects of AR on brand recall across varying product presentation strategies. Our results indicate that while AR technology significantly enhances brand recall in multi-product collocation contexts, it does not consistently outperform traditional non-AR methods, such as 3D displays, in single-product presentations. These findings add to the expanding literature on AR marketing by providing nuanced evidence of the conditions under which AR is most effective, offering valuable guidance for marketers aiming to strategically leverage AR technology in their branding efforts.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Augmented Reality and Brand Management

While AR marketing has been extensively studied in the context of the purchase and post-purchase stages—particularly with respect to its impact on consumer purchase intentions [20,21,22,23], willingness to pay [9], and product evaluations [24]—research on its role in the pre-purchase stage remains underdeveloped. Much of the existing research has focused on AR’s ability to enhance post-purchase consumer behaviors such as recommendation intentions [25], patronage intentions [26], and other behavioral intentions [27,28].

The pre-purchase stage, however, is critical for establishing brand awareness, capturing consumer attention, and deepening brand impressions [14]. Existing studies have primarily examined how AR’s immersive experiences influence consumer perceptions of brand image, brand attitude, and brand engagement [28,29,30,31,32]. Moreover, AR has been shown to foster consumer–brand relationships by offering rich, interactive experiences that engage consumers on a deeper emotional level [33,34].

Given that brand awareness is a foundational element of brand equity and market success [35], the lack of research on AR’s effects in the pre-purchase stage presents a critical gap. The ability to create memorable brand impressions and increase brand importance at the outset of the customer journey is essential for guiding consumers through subsequent stages.

2.2. Brand Recall

Brand recall refers to the consumer’s ability to retrieve a brand name from memory, either spontaneously or when provided with a related cue [15,36]. It plays a critical role in the formation of brand equity, as a brand’s recall influences whether it is considered during the consumer’s decision-making process [15]. Greater brand recall enhances the likelihood that a brand will be evaluated and potentially chosen during shopping [37]. Therefore, researching brand recall is vital to understanding how brands can secure a favorable position in consumer evaluations.

Previous research on brand recall has been somewhat fragmented, focusing largely on consumer responses to advertising contexts and the ability to recall brands under varying conditions. A significant portion of the literature has explored the relationship between product placement and brand recall. For example, Chaney et al. (2018) [38] demonstrated that large brand placements in racing games more effectively capture consumer attention, leading to higher recall and recognition rates. Similarly, Vashisht and Royne (2016) [39] investigated the interaction between advergame speed and brand placement intensity on recall, using the Limited Capacity Model (LCM) of attention to explain how these factors influence memory retention. These studies generally attribute brand recall to stimuli that capture attention and support memory encoding [40,41,42,43].

Although research on brand recall has offered insights into the role of attention and memory in advertising contexts, there has been limited exploration in newer marketing environments, such as AR. Additionally, theoretical explanations for brand recall have predominantly relied on attention and memory models, with little consideration for alternative frameworks.

2.3. Embodied Cognition Theory

Embodied cognition posits that cognitive processes are fundamentally shaped by the body’s interactions with the environment, suggesting that thinking is not solely abstract but is grounded in physical experiences [18,19,44,45]. This theory asserts that cognition arises through dynamic interactions between the body, the mind, and the surrounding environment, with bodily movements, postures, and sensory experiences playing an active role in shaping thought processes [18]. Embodied cognition further emphasizes that cognition is situated and context-dependent, influenced by the physical and social cues present in the environment [44,46,47].

The continuous interaction between sensory and motor systems and the environment is integral to cognitive processes, with these systems constantly shaping perception, memory, and decision making [45,48]. In this view, cognition is not an isolated mental activity but is deeply rooted in concrete experiences and contexts [49]. This framework provides a holistic understanding of how individuals process information by engaging with their environment.

In consumer behavior research, embodied cognition has been applied to explore the effects of environmental stimuli on memory and decision making. For instance, Van Rompay et al. (2012) [50] demonstrated how visual environmental cues influence consumer shopping behavior, while Hong and Sun (2012) [51] and Lee et al. (2014) [47] found that ambient temperature affects consumption behavior and social relationships. Similarly, Van Kerckhove et al. (2015) [52] showed that bodily movements, such as head and body orientation, affect information processing, evaluation, and decision making. These studies illustrate how sensory–motor experiences directly inform cognition and consumer responses.

Moreover, research has integrated embodied cognition theory with sensory marketing to investigate how sensory cues influence perception, judgment, and memory [53,54,55,56,57]. The advancement of immersive technologies, such as virtual reality (VR) and AR, has enabled the simulation of specific consumption scenarios that enhance consumer perception and engagement, thereby providing immersive experiences that reinforce embodied cognition [58]. However, there remains a notable gap in research that combines embodied cognition theory with AR marketing. Existing studies have yet to fully explore how AR technology, by facilitating interactions with virtual environments, impacts consumer memory and brand recall.

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Augmented Reality and Brand Recall

AR-based product presentation leverages the unique capabilities of AR technology to integrate virtual products into consumers’ physical environments, seamlessly blending them with real-world surroundings. This feature, referred to as environmental embedding, is defined as the visual integration of virtual content within a person’s immediate environment [17]. Environmental embedding distinguishes AR-based product presentations from traditional online formats by allowing consumers to visualize products within a realistic context, thereby enhancing the perceptual experience [59]. When consumers interact with products through AR, they do not merely imagine product usage but instead engage with the product in a simulated real-world context, allowing for a more embodied interaction that fosters personal judgments and assessments [47].

Embodied cognition theory asserts that cognitive processes are inherently linked to physical experiences and interactions within a given environment [60]. According to this framework, cognition is situated and emerges from the interaction between the individual and the environment, emphasizing the role of context in shaping memory and decision making [61,62]. Prior research has demonstrated that embodied activities, such as interacting with physical or virtual objects, can enhance cognitive functions such as memory encoding and retrieval [63]. Specifically, memory is distributed across the body and the environment, with situational cues serving as anchors for cognitive processes [64,65]. Given this, as product presentation formats evolve from static 3D models to immersive AR, the strength of embodied cognition increases, leading to deeper consumer interactions with the environment and a more profound understanding of the brand within the context of use.

Additionally, unlike traditional online shopping experiences that rely on flat, two-dimensional screens, AR offers consumers a multi-sensory, spatially rich experience [24]. In AR environments, consumers do not simply view products; they physically move through space, adjust their perspectives, and interact with virtual objects, thereby heightening their sense of involvement [66,67]. Such immersive and multi-dimensional experiences are more likely to capture consumer attention and leave lasting impressions on memory [68,69]. For example, when consumers interact with virtual products through AR gestures, such as “placing” a virtual table in their home, the sensory experience more closely mirrors the physical shopping process [24]. This interaction fosters an emotional connection with the product and the brand, as consumers feel a sense of ownership and placement within their own space [33,34,70]. This heightened emotional engagement strengthens the bond between consumers and the brand, thereby enhancing brand memory [34]. Given the potential of AR to facilitate deeper cognitive and emotional engagement, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

AR-based (vs. non-AR) product presentation enhances consumers’ brand recall.

3.2. The Moderating Effect of Product Presentation Strategies

Product presentation strategies play a pivotal role in guiding consumer information processing and shaping their overall shopping experience [71,72]. While extensive research has investigated the impact of presenting products individually versus in bundles on consumer evaluations, selection, willingness to pay, and purchase intentions [73,74,75,76], relatively little attention has been paid to how these strategies might influence brand recall, particularly within the context of AR technology, which offers a unique blend of immersion and contextual richness [30].

Drawing on embodied cognition theory, which posits that cognitive processes are fundamentally shaped by physical interactions with the environment [18,19]. In conjunction with the principles of associative network theory, when a concept is activated (e.g., seeing a table), this activation spreads along the network’s edges, triggering related concepts (e.g., chairs or other furniture) [77,78]. AR environment enhances this multi-item association effect because consumers are not just viewing a single product or a model of products grouped together—they are immersed in a more complete context. This approach not only helps consumers better understand the product’s usage scenario but also strengthens the associations between these products in the consumer’s mind through visual and contextual cues [79]. We propose that the way in which products are presented could significantly influence the encoding and retrieval of brand information in memory [77,80]. Specifically, the degree of sensory and contextual engagement offered by AR might vary depending on whether products are presented separately or in collocation.

We speculate that in separate presentation strategies, where products are shown individually, the benefits of AR might be less pronounced. Without the presence of additional contextual cues or related products, the immersive and embodied advantages provided by AR could be limited [81]. In such cases, the depth of sensory engagement may not be sufficient to create a significant difference in brand recall between AR and non-AR formats [58]. The absence of competing stimuli in non-AR formats could allow for focused attention on the individual product, potentially leading to similar levels of memory encoding as those seen in AR presentations.

In contrast, we anticipate that in collocation presentation strategies, AR might demonstrate a more substantial advantage. The immersive capabilities of AR could enable consumers to experience products within a cohesive, contextually enriched environment [82], thereby fostering stronger associative links between the items presented (e.g., a table and matching chairs) [77,80]. This contextually rich scenario, supported by embodied cognition, may facilitate deeper memory processing and enhance brand recall, as multiple cognitive pathways, such as spatial perception and embodied interaction, are engaged [30,58,81,82].

Thus, we hypothesize that the interaction between product presentation formats (AR vs. Non-AR) and presentation strategies (separate vs. collocation) could lead to varying levels of brand recall. Specifically, we expect AR’s impact on brand recall to be more pronounced in collocation contexts, where its immersive and associative qualities can be fully leveraged. Conversely, in separate contexts, the lack of a rich, interactive environment might diminish AR’s potential advantage, resulting in more comparable brand recall outcomes across the two formats.

Based on this reasoning, we hypothesize the following:

H2.

The effects of product presentation formats (AR vs. non-AR) on brand recall are moderated by product presentation strategies (separate vs. collocation), with AR expected to be more effective in collocation contexts.

The research model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Empirical Studies

To empirically test our hypotheses, we conducted two controlled laboratory studies. Study 1 focused on examining the direct effect of product presentation formats (AR vs. non-AR) on brand recall, as proposed in Hypothesis 1. Study 2 employed a 2 (AR vs. non-AR) × 2 (separate vs. collocation) between-subjects design to explore the interaction between product presentation formats and presentation strategies on brand recall, addressing Hypothesis 2.

4.1. Study 1

4.1.1. Participants and Design

Study 1 utilized a one-factor, two-levels (AR vs. non-AR) between-subjects design. A total of 60 participants were recruited through both online and offline channels, randomly divided into two groups, with 30 participants assigned to each group. Participants were compensated CNY 10 for their participation. The sample consisted of 10 males (16.7%) and 50 females (83.3%), ranging in age from 18 to 45 years, with an average age of 20.80 years. All participants reported prior experience with online shopping. The demographic characteristics of the participants are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the participants (Study 1).

4.1.2. Measures

Brand recall served as the dependent variable across all measurements, following established methodologies from previous studies [41,83,84]. To assess brand recall, participants were asked to write down the brand names they remembered from the shopping experience. The responses were then coded as binary outcomes, with correct recall recorded as 1 and incorrect recall as 0.

4.1.3. Materials and Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. At the outset of the experiment, participants were briefed on the experimental scenario: they had an empty study room that needed furnishing, and their task was to purchase a desk. Both groups were presented with a set of furniture items, including a desk, chair, bookshelf, and sofa.

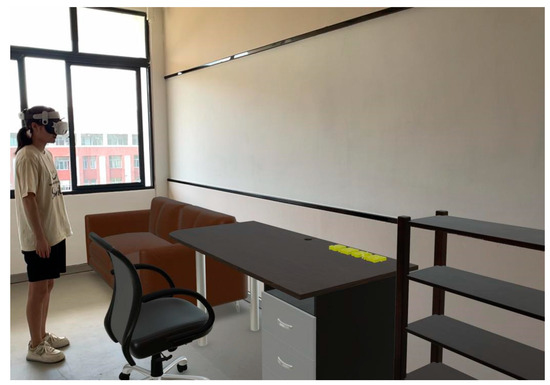

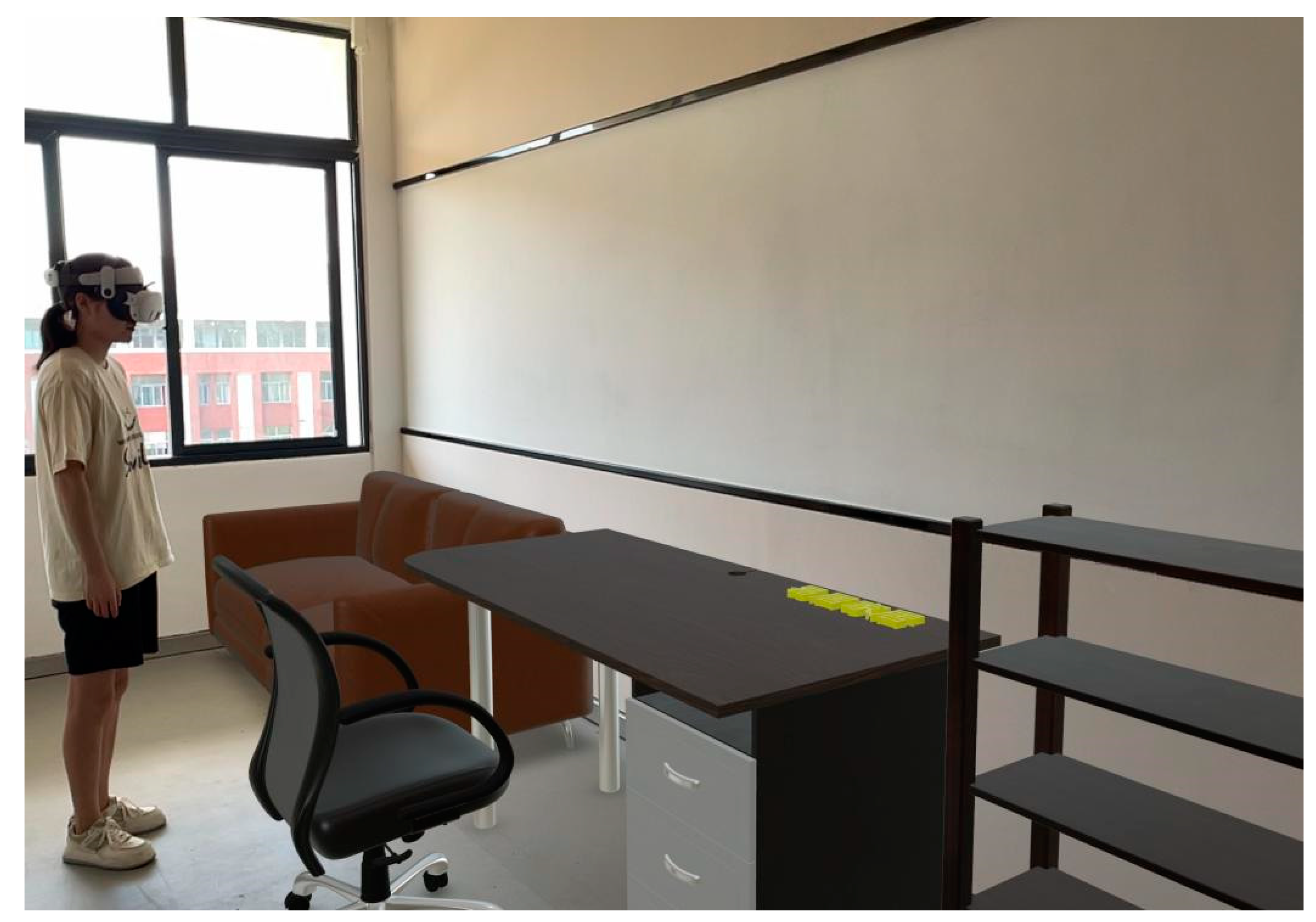

Participants first browsed basic product information on a mobile tablet, which included the product name, description, material, and dimensions. The non-AR group viewed a 3D model of the furniture set on the tablet against a white background (refer to Figure A1 in Appendix A). This model could be zoomed, rotated, and explored in detail. In contrast, participants in the AR group, after browsing the same product information on the tablet, were provided with a Meta Quest 3 headset for an immersive AR experience. This allowed them to view the furniture items as if they were placed in a simulated version of their study room (refer to Appendix A Figure A3). They could examine the products from various angles and inspect details such as color, size, and material. Participants in both groups were allowed to take as much time as they needed to view the products. Upon completion of the viewing session, participants filled out a questionnaire.

A fictional brand name, “Yiju Home Furnishings” (a Chinese literal translation), was used for the study, and the brand name was only displayed on the desk model in yellow text at the upper right corner. To control for consumer interaction, particularly in the AR experience, participants were not allowed to manipulate the products directly; instead, the AR technology utilized environmental embedding to virtually place the products within the study room. The product arrangement was kept consistent across both conditions to ensure comparability. Additionally, participants in the AR group were given approximately one minute to acclimate to the AR equipment, minimizing the potential novelty effects of the device and technology on the experimental outcomes.

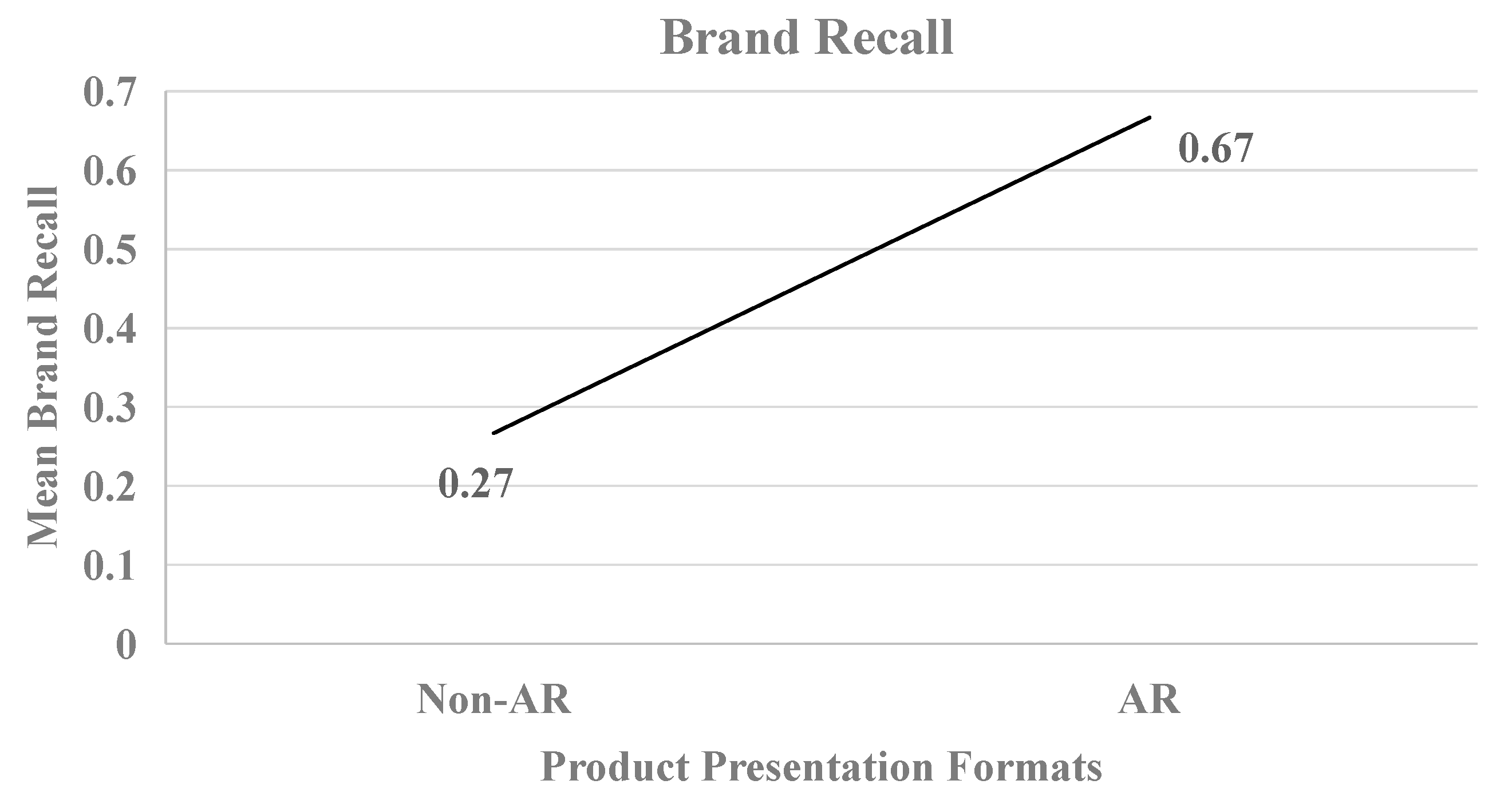

4.1.4. Results

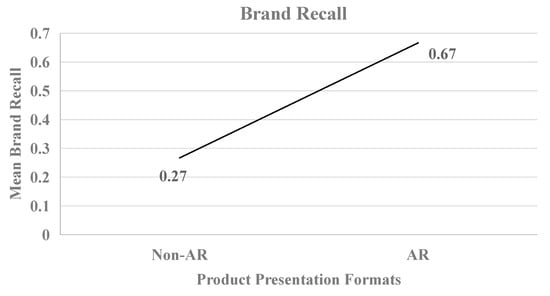

To analyze the relationship between product presentation formats and brand recall, we conducted an ANOVA with brand recall as the dependent variable and product presentation formats (AR vs. non-AR) as the independent variable. The results indicated a significant difference in brand recall between the two formats. Specifically, participants in the AR group exhibited higher brand recall compared to those in the non-AR group (MAR = 0.67, MNon-AR = 0.27, F(1, 58) = 11.11, p < 0.01), as illustrated in Figure 2. These findings support Hypothesis 1.

Figure 2.

Effects of product presentation formats on brand recall.

In Study 1, after the sample was randomly divided into groups; there was a gender imbalance among the experiment participants (83.3% female, 16.7% male). To examine whether participants’ gender would influence brand recall, we included gender as a covariate for further analysis. The results show that gender had no significant effect on brand recall (p > 0.2) and product presentation formats (AR vs. non-AR) had a significant effect on brand recall (p < 0.01), indicating that participants’ gender did not influence brand recall in Study 1.

4.2. Study 2

4.2.1. Participants and Design

Study 2 employed a 2 (AR vs. non-AR) × 2 (separate vs. collocation) between-subjects design with 45 participants randomly divided into each of the four experimental conditions. A total of 180 participants were recruited through a combination of online and offline channels, with each participant receiving CNY 10 as compensation for their time. The sample comprised 25 males and 155 females, ranging in age from 18 to 45 years, with an average age of 21.56 years. All participants reported prior experience with online shopping. The demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic profile of the participants (Study 2).

4.2.2. Materials and Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions, reflecting the combination of product presentation format (AR vs. non-AR) and presentation strategy (separate vs. collocation). The experimental procedures and measurements closely mirrored those employed in Study 1. In the non-AR conditions, participants viewed either a 3D model of a single product (the desk) or a 3D model of multiple products displayed against a white background on a tablet (refer to Appendix A; Figure A1 and Figure A2). In the AR conditions, participants used an iPad Pro (11-inch, 3rd generation) equipped with a LiDAR Scanner to experience a non-immersive AR view, wherein the products were placed in a simulated version of their study room (refer to Appendix A; Figure A4 and Figure A5). Participants were able to explore the products from various angles and observe details such as color, size, and material. They were permitted to spend as much time as needed to view the products.

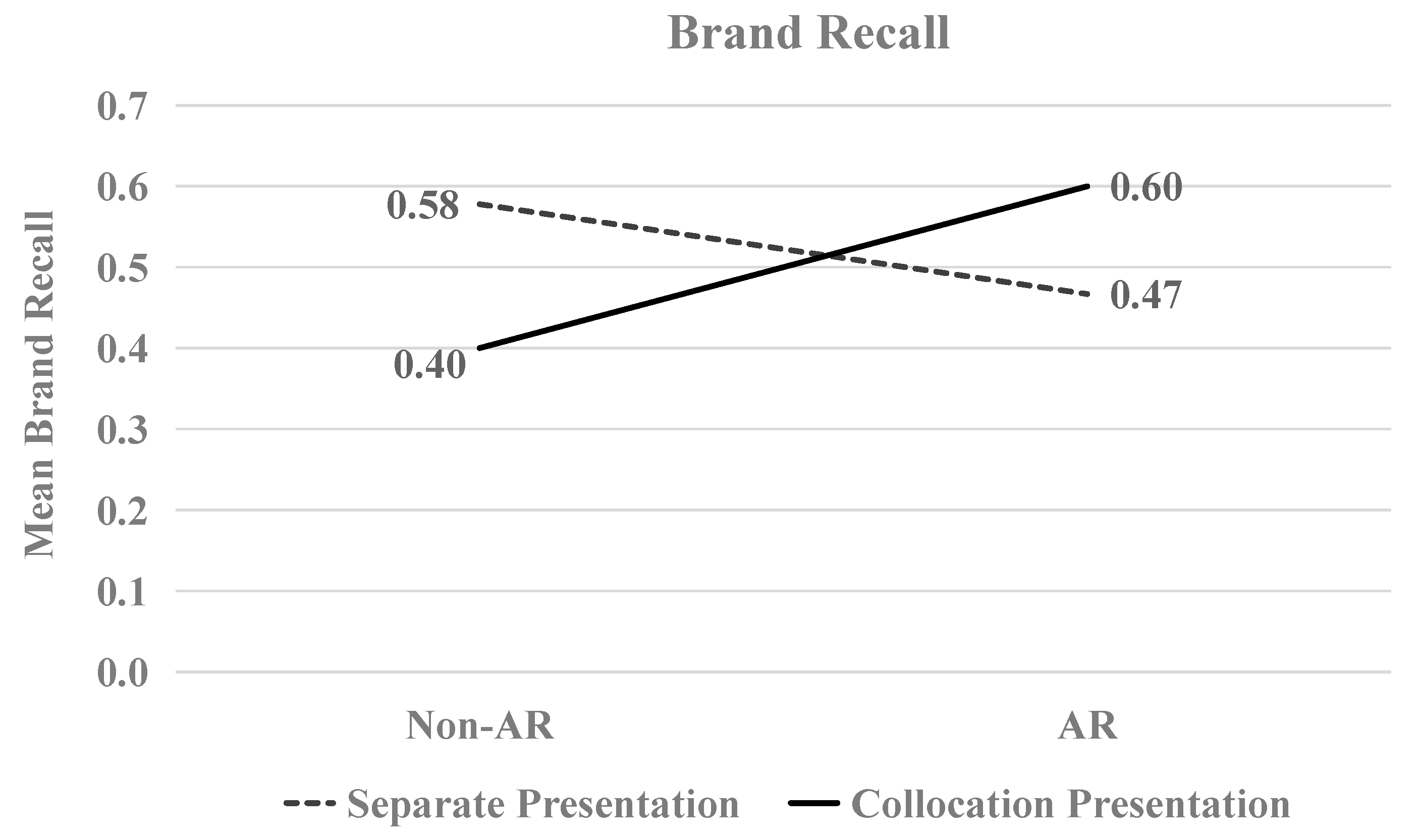

4.2.3. Results

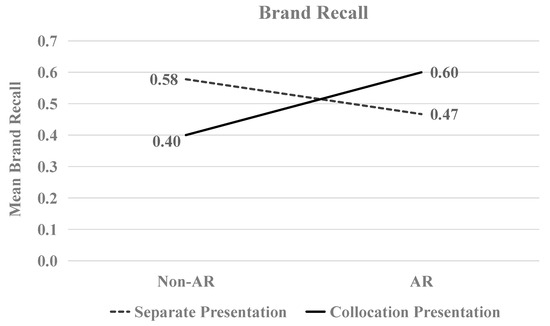

To assess the interaction effect of product presentation formats (AR vs. non-AR) and presentation strategies (separate vs. collocation) on consumer brand recall, an ANOVA was conducted. The analysis revealed a significant interaction effect between the product presentation format and the presentation strategy on brand recall (F(1, 176) = 4.378, p < 0.05), as illustrated in Figure 3. In separate product presentations, no significant difference in brand recall was observed between the AR and non-AR formats (MNon-AR = 0.58, MAR = 0.47, p > 0.2). In contrast, in collocation presentations, the AR format resulted in significantly higher brand recall compared to the non-AR format (MAR = 0.60, MNon-AR = 0.40, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Figure 3.

The interaction effect between product presentation formats and product presentation strategies on brand recall.

A situation similar to Study 1, in Study 2, there was a gender imbalance among the experiment participants (86.1% female; 13.9% male). To examine whether participants’ gender would influence brand recall, we included gender as a covariate for further analysis. The results show that gender had no significant effect on brand recall (p > 0.5); the interaction between product presentation format and presentation strategy has a significant effect on brand recall (p < 0.05), indicating that participants’ gender did not influence brand recall in Study 2.

5. General Discussion

5.1. Research Finding

This research offers a comprehensive examination of how product presentation strategies—separate versus collocation—and presentation formats (AR vs. non-AR) interact to influence consumer brand recall. Drawing on embodied cognition theory, our findings reveal that AR technology significantly enhances memory processes in specific contexts. In particular, AR-based presentations are most effective in multi-product collocation scenarios, where the immersive experience facilitates stronger cognitive and emotional connections with the brand. This supports the notion that cognitive processes are deeply intertwined with physical interactions within contextually rich environments, as enabled by AR [17].

However, when products are presented individually, the advantages of AR become less pronounced. Our results suggest that in these separate presentation contexts, traditional non-AR formats may even show a slight, though not statistically significant, edge in brand recall. This indicates that AR’s effectiveness is highly context-dependent, thriving in scenarios where it can leverage the richness of multiple related products being presented together. Thus, AR’s potential to enhance brand recall is maximized when the technology is used in a way that aligns with the cognitive processes it is designed to influence.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

This study contributes to the literature by expanding the application of embodied cognition theory within the realm of AR-enhanced consumer behavior, specifically addressing the early stages of the consumer decision-making process, such as brand recall. Traditionally, consumer memory and decision-making research have been dominated by attention-based models, which primarily focus on how visual and cognitive attention influence consumer preferences [41,43,85,86]. Our research challenges this paradigm by demonstrating that embodied cognition provides a more appropriate theoretical framework for understanding the effects of AR [58], particularly how physical interactions within simulated environments can enhance memory retention.

Furthermore, our study addresses a significant gap in the literature by focusing on the impact of AR on brand recall, an early yet critical stage in the consumer journey that has been relatively underexplored. Previous studies have largely concentrated on the later stages, such as purchase intentions [22,87,88] and product evaluations [24], neglecting the foundational role that brand recall plays in guiding consumer choices. By investigating how AR influences brand recall, this research offers new insights into the strategic potential of AR technology in strengthening brand equity from the outset of the consumer journey.

In addition, our research contributes to the broader AR marketing literature by empirically testing the differential effects of AR and non-AR presentation formats across varying product presentation strategies. The findings reveal that AR’s effectiveness is not uniform but rather contingent on the specific presentation context. Specifically, while AR excels in multi-product collocation scenarios, its advantages are less evident in single-product presentations. This nuanced understanding enriches the theoretical discourse on AR’s role in marketing and provides practical implications for marketers seeking to optimize the deployment of AR in their branding efforts.

5.3. Practical Contribution

This research offers valuable practical insights for brand marketers aiming to leverage AR technology to enhance brand recall. The study’s findings demonstrate that AR-based presentations, particularly in multi-product collocation contexts, can significantly improve consumer brand recall. This suggests that companies should integrate AR into their branding strategies to create more engaging and memorable brand narratives, which are crucial for capturing and retaining consumer attention in an increasingly competitive market [89]. AR’s ability to simulate real-world usage scenarios provides consumers with a more immersive and context-rich experience [90], which strengthens brand associations and recall.

Moreover, the research highlights the importance of aligning product presentation strategies with the appropriate technology. The findings suggest that while AR is highly effective in multi-product collocation contexts, traditional 3D displays may be more suitable for single-product presentations where the goal is to focus consumer attention on one item. This strategic alignment between presentation format and context can maximize the impact on brand recall, offering marketers a more sophisticated approach to product presentation in both online and offline environments [91].

Additionally, the study provides evidence for the practical integration of AR technology into brand marketing strategies. By demonstrating the conditions under which AR is most effective, the research offers marketers a roadmap for using AR to its full potential, ensuring that the technology is employed in scenarios where it can most significantly enhance consumer engagement and brand recall [92].

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that offer avenues for future research. Firstly, our experimental design focused primarily on the environmental embedding feature of AR technology and its impact on consumer brand recall. We did not explore the interactive capabilities of AR, which could potentially have significant effects on consumer attitudes and emotional responses [93], particularly under varying product recommendation contexts [94,95]. Future research should consider integrating both the environmental embedding and interactive features of AR to examine their combined effects on consumer creativity and the co-creation of value between consumers and brands.

Secondly, our study was limited to furniture products, which may not fully represent the diversity of consumer goods. Different product categories could influence consumer purchase intentions, brand awareness, and the overall relationship between consumers and brands [81,96,97]. Future research should explore how product type moderates the effects of AR on consumer behavior, examining a broader range of products to understand the generalizability of our findings across different market segments.

Finally, our experimental sample was primarily recruited from a finance university, where the high proportion of female students resulted in a gender imbalance in our sample. Although further tests demonstrated that gender had no significant impact on our final research results, this remains an influencing factor that we need to explore and consider in our future experimental research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and L.N.; methodology, L.N.; software, T.Z. and L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z. and L.N.; writing—review and editing, L.Z. and T.Z.; project administration, L.Z.; funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Projects: 72362006; 72472060), Guizhou Provincial Big Data Industry Innovation and Development Laboratory ([2023]02), and the Guizhou Provincial Department of Education’s Higher Education Scientific Research Project ([2022]176).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it did not involve any interventions or procedures that required ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Experimental condition: non-AR presentation and collocation strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A1.

Experimental condition: non-AR presentation and collocation strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A2.

Experimental condition: non-AR presentation and separate strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A2.

Experimental condition: non-AR presentation and separate strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A3.

Experimental condition: AR-based presentation and collocation strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A3.

Experimental condition: AR-based presentation and collocation strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A4.

Experimental condition: AR-based presentation and collocation strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A4.

Experimental condition: AR-based presentation and collocation strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A5.

Experimental condition: AR-based presentation and separate strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

Figure A5.

Experimental condition: AR-based presentation and separate strategy. The yellow Chinese characters “易居家居” on the table refer to the brand name “Yijia Home”.

References

- Hee Lee, J.; Shvetsova, O.A. The impact of VR application on student’s competency development: A comparative study of regular and VR engineering classes with similar competency scopes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacca-Acosta, J.; Avila-Garzon, C.; Sierra-Puentes, M. Insights into the Predictors of Empathy in Virtual Reality Environments. Information 2023, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ruyter, K.; Heller, J.; Hilken, T.; Chylinski, M.; Keeling, D.I.; Mahr, D. Seeing with the customer’s eye: Exploring the challenges and opportunities of AR advertising. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Au, S.; Rauschnabel, P.A.; Felix, R.; Hinsch, C. Context in augmented reality marketing: Does the place of use matter? Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 2447–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Orús, C. The impact of virtual, augmented and mixed reality technologies on the customer experience. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javornik, A.; Marder, B.; Pizzetti, M.; Warlop, L. Augmented self-The effects of virtual face augmentation on consumers’ self-concept. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, A.; Hilken, T.; Chylinski, M.; Mahr, D.; Heller, J.; Keeling, D.I.; de Ruyter, K. The playground effect: How augmented reality drives creative customer engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Rauschnabel, P.A.; Agarwal, M.N.; Singh, R.K.; Srivastava, R. Towards a theoretical framework for augmented reality marketing: A means-end chain perspective on retailing. Inf. Manag. 2024, 61, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.; Chylinski, M.; de Ruyter, K.; Mahr, D.; Keeling, D.I. Touching the untouchable: Exploring multi-sensory augmented reality in the context of online retailing. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, M.; Bigné, E.; Zhang, J. Virtual and augmented reality: Advancing research in consumer marketing. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.C.; Chandukala, S.R.; Reddy, S.K. Augmented reality in retail and its impact on sales. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschnabel, P.A.; Babin, B.J.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Krey, N.; Jung, T. What is augmented reality marketing? Its definition, complexity, and future. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 1140–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabadayi, E.T.; Alan, A. Brand trust and brand affect: Their strategic importance on brand loyalty. J. Glob. Strateg. Manag. 2012, 11, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.; Stocchi, L.; Gruber, T.; Romaniuk, J. Advancing the understanding of the pre-purchase stage of the customer journey for service brands. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 360–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H. Relationship between Brand Experience, Local Presence, Flow, and Brand Attitude While Applying Spatial Augmented Reality to a Brand Store. Int. J. Hum. –Comput. Interact. 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilken, T.; De Ruyter, K.; Chylinski, M.; Mahr, D.; Keeling, D.I. Augmenting the eye of the beholder: Exploring the strategic potential of augmented reality to enhance online service experiences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 884–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L.W. Perceptual symbol systems. Behav. Brain Sci. 1999, 22, 577–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedenthal, P.M.; Barsalou, L.W.; Winkielman, P.; Krauth-Gruber, S.; Ric, F. Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 9, 184–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoye, V.; Tarkiainen, A.; Sipilä, J.; Mero, J. More than skin-deep: The influence of presence dimensions on purchase intentions in augmented reality shopping. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 169, 114247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilken, T.; Heller, J.; Keeling, D.I.; Chylinski, M.; Mahr, D.; de Ruyter, K. Bridging imagination gaps on the path to purchase with augmented reality: Field and experimental evidence. J. Interact. Mark. 2022, 57, 356–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Clement, A.P. Following the flow: Exploring the impact of mobile technology environment on user’s virtual experience and behavioral response. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.; Park, M. Imagery evoking visual and verbal information presentations in mobile commerce: The roles of augmented reality and product review. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 18, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangrath, A.W.; Peck, J.; Hedgcock, W.; Xu, Y. Observing product touch: The vicarious haptic effect in digital marketing and virtual reality. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 59, 306–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilken, T.; Keeling, D.I.; de Ruyter, K.; Mahr, D.; Chylinski, M. Seeing eye to eye: Social augmented reality and shared decision making in the marketplace. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, F.; Lv, S.; Han, W. Mechanism linking AR-based presentation mode and consumers’ responses: A moderated serial mediation model. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2694–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.; Chylinski, M.; de Ruyter, K.; Mahr, D.; Keeling, D.I. Let me imagine that for you: Transforming the retail frontline through augmenting customer mental imagery ability. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrove, A.; Sommer, J.M.; Jones, J.J. Virtual reality and embodied experience induce similar levels of empathy change: Experimental evidence. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2020, 2, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschnabel, P.A.; Felix, R.; Hinsch, C. Augmented reality marketing: How mobile AR-apps can improve brands through inspiration. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Amorim, I.P.; Guerreiro, J.; Eloy, S.; Loureiro, S.M.C. How augmented reality media richness influences consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 2351–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Joerß, T.; Mai, R.; Akbar, P. Augmented reality-delivered product information at the point of sale: When information controllability backfires. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 743–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanger, V.; Meißner, M.; Rauschnabel, P.A. Beyond the gimmick: How affective responses drive brand attitudes and intentions in augmented reality marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Yoo, C.Y.; Yoon, S. Augment yourself through virtual mirror: The impact of self-viewing and narcissism on consumer responses. Int. J. Advert. 2018, 37, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J.; Duffy, K. We ARe at home: How augmented reality reshapes mobile marketing and consumer-brand relationships. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.S.; Siddiqui, U.A.; Khan, M.A.; Alkandi, I.G.; Saxena, A.K.; Siddiqui, J.H. Creating electronic word of mouth credibility through social networking sites and determining its impact on brand image and online purchase intentions in India. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, C.; Hamin, H.; Chong, A. The role of brand exposure and experience on brand recall—Product durables vis-à-vis FMCG. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 23, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedungadi, P. Recall and consumer consideration sets: Influencing choice without altering brand evaluations. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, I.; Hosany, S.; Wu MS, S.; Chen CH, S.; Nguyen, B. Size does matter: Effects of in-game advertising stimuli on brand recall and brand recognition. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisht, D.; Royne, M.B. Advergame speed influence and brand recall: The moderating effects of brand placement strength and gamers’ persuasion knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baack, D.W.; Wilson, R.T.; Till, B.D. Creativity and memory effects: Recall, recognition, and an exploration of nontraditional media. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davtyan, D.; Stewart, K.; Cunningham, I. Comparing brand placements and advertisements on brand recall and recognition. J. Advert. Res. 2016, 56, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashist, D. Effect of product involvement and brand prominence on advergamers’ brand recall and brand attitude in an emerging market context. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.D.; Deitz, G.D.; Huhmann, B.A.; Jha, S.; Tatara, J.H. An eye-tracking study of attention to brand-identifying content and recall of taboo advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 111, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarini, F.; Adenzato, M. At the root of embodied cognition: Cognitive science meets neurophysiology. Brain Cogn. 2004, 56, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, A.; Schwarz, N. Sensory marketing, embodiment, and grounded cognition: A review and introduction. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedenthal, P.M.; Winkielman, P.; Mondillon, L.; Vermeulen, N. Embodiment of emotion concepts. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee SH, M.; Rotman, J.D.; Perkins, A.W. Embodied cognition and social consumption: Self-regulating temperature through social products and behaviors. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, A.; Lee, S.W.; Li, X.; Schwarz, N. Embodied cognition, sensory marketing, and the conceptualization of consumers’ judgment and decision processes: Introduction to the issue. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2017, 2, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelen, J.; Dewitte, S.; Warlop, L. Situated embodied cognition: Monitoring orientation cues affects product evaluation and choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 2013, 23, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rompay, T.J.; De Vries, P.W.; Bontekoe, F.; Tanja-Dijkstra, K. Embodied product perception: Effects of verticality cues in advertising and packaging design on consumer impressions and price expectations. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Sun, Y. Warm it up with love: The effect of physical coldness on liking of romance movies. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kerckhove, A.; Geuens, M.; Vermeir, I. The floor is nearer than the sky: How looking up or down affects construal level. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 41, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J.; Childers, T.L. To have and to hold: The influence of haptic information on product judgments. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J.; Wiggins, J. It just feels good: Customers’ affective response to touch and its influence on persuasion. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, A.; Lwin, M.O.; Morrin, M. Product scent and memory. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. An integrative review of sensory marketing: Engaging the senses to affect perception, judgment and behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelet, C. Mobile advertising: The effect of tablet tilt angle on user’s purchase intentions. J. Mark. Commun. 2020, 26, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, O.; Velasco, C.; Spence, C. Digital sensory marketing: Integrating new technologies into multisensory online experience. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, R.S.; Krishna, A. The “visual depiction effect” in advertising: Facilitating embodied mental simulation through product orientation. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. Six views of embodied cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2002, 9, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSutter, D.; Stieff, M. Teaching students to think spatially through embodied actions: Design principles for learning environments in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2017, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinnamon, C.; Miller, E. Architectural concept design process impacted by body and movement. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2022, 32, 1079–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, M.; Trumpp, N.M. Embodiment theory and education: The foundations of cognition in perception and action. Trends Neurosci. Educ. 2012, 1, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, J.S.; Yanchar, S.C. Embodied cognition, representationalism, and mechanism: A review and analysis. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2014, 44, 46–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Alonso, J.C.; Paas, F.; Ginns, P. Embodied cognition, science education, and visuospatial processing. In Visuospatial Processing for Education in Health and Natural Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 175–205. [Google Scholar]

- Celsi, R.L.; Olson, J.C. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behe, B.K.; Bae, M.; Huddleston, P.T.; Sage, L. The effect of involvement on visual attention and product choice. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianì, F. Embodied memories: Reviewing the role of the body in memory processes. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2019, 26, 1747–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.V. Learning and embodied cognition: A review and proposal. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 2018, 17, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzi, A.; Chylinski, M.; Heller, J.; Hilken, T.; Keeling, D.I.; de Ruyter, K. What’s mine is a hologram? How shared augmented reality augments psychological ownership. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 48, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Thong, J.Y.; Tam, K.Y. The effects of information format and shopping task on consumers’ online shopping behavior: A cognitive fit perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2004, 21, 149–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rixom, J.M.; Mas, E.M.; Rixom, B.A. Presentation matters: The effect of wrapping neatness on gift attitudes. J. Consum. Psychol. 2020, 30, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xia, L. Joint or separate? The effect of visual presentation on imagery and product evaluation. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdenger, T.; Kumar, V. The dynamic effects of bundling as a product strategy. Mark. Sci. 2013, 32, 827–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Song, J.D. Impact of mixed bundling type on consumers’ value perception. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 2167–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.H.; Chou, H.Y. The effects of promotional frames of sales packages on perceived price increases and repurchase intentions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 32, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Osselaer, S.M.; Janiszewski, C. Two ways of learning brand associations. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.R.; Iacobucci, D.; Calder, B.J. Brand diagnostics: Mapping branding effects using consumer associative networks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 111, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajanki, A.; Billinghurst, M.; Gamper, H.; Järvenpää, T.; Kandemir, M.; Kaski, S.; Koskela, M.; Kurimo, M.; Laaksonen, J.; Puolamäki, K.; et al. An augmented reality interface to contextual information. Virtual Real. 2011, 15, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R. A spreading activation theory of memory. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1983, 22, 261–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, X. Beyond presence: Creating attractive online retailing stores through the cool AR technology. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1139–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- tom Dieck, M.C.; Cranmer, E.; Prim, A.L.; Bamford, D. The effects of augmented reality shopping experiences: Immersion, presence and satisfaction. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 940–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.S.; Kerr, G.; Suh, J. Impairment effects of creative ads on brand recall for other ads. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1466–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.W.; Chattopadhyay, A. Salience effects in brand recall. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuisma, J.; Simola, J.; Uusitalo, L.; Öörni, A. The effects of animation and format on the perception and memory of online advertising. J. Interact. Mark. 2010, 24, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujur, F.; Singh, S. Visual communication and consumer-brand relationship on social networking sites-uses & gratifications theory perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilken, T.; Chylinski, M.; Keeling, D.I.; Heller, J.; de Ruyter, K.; Mahr, D. How to strategically choose or combine augmented and virtual reality for improved online experiential retailing. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaff, A.; Spann, M. When reality backfires: Product evaluation context and the effectiveness of augmented reality in e-commerce. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 2413–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewski, C.; Kuo, A.; Tavassoli, N.T. The influence of selective attention and inattention to products on subsequent choice. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 1258–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim MY, C.; Chu, S.C.; Sauer, P.L. Is augmented reality technology an effective tool for e-commerce? An interactivity and vividness perspective. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 39, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, A.R.; Van Reijmersdal, E.A.; Van Noort, G.; Neijens, P.C. Shopping in augmented reality: The effects of spatial presence, personalization and intrusiveness on app and brand responses. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 118, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Wilson, A. Shopping in the digital world: Examining customer engagement through augmented reality mobile applications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.; Shin, J.H.; Ponto, K. How 3D virtual reality stores can shape consumer purchase decisions: The roles of informativeness and playfulness. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 49, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, Q.; Jung, S. The impact of recommendation system on user satisfaction: A moderated mediation approach. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senecal, S.; Nantel, J. The influence of online product recommendations on consumers’ online choices. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Abbasi, A.; Cheema, A.; Abraham, L.B. Path to purpose? How online customer journeys differ for hedonic versus utilitarian purchases. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H. The Impact of Topological Structure, Product Category, and Online Reviews on Co-Purchase: A Network Perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 548–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).