How Does the Relevance of Firm-Generated Content to Products Affect Consumer Brand Attitudes?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

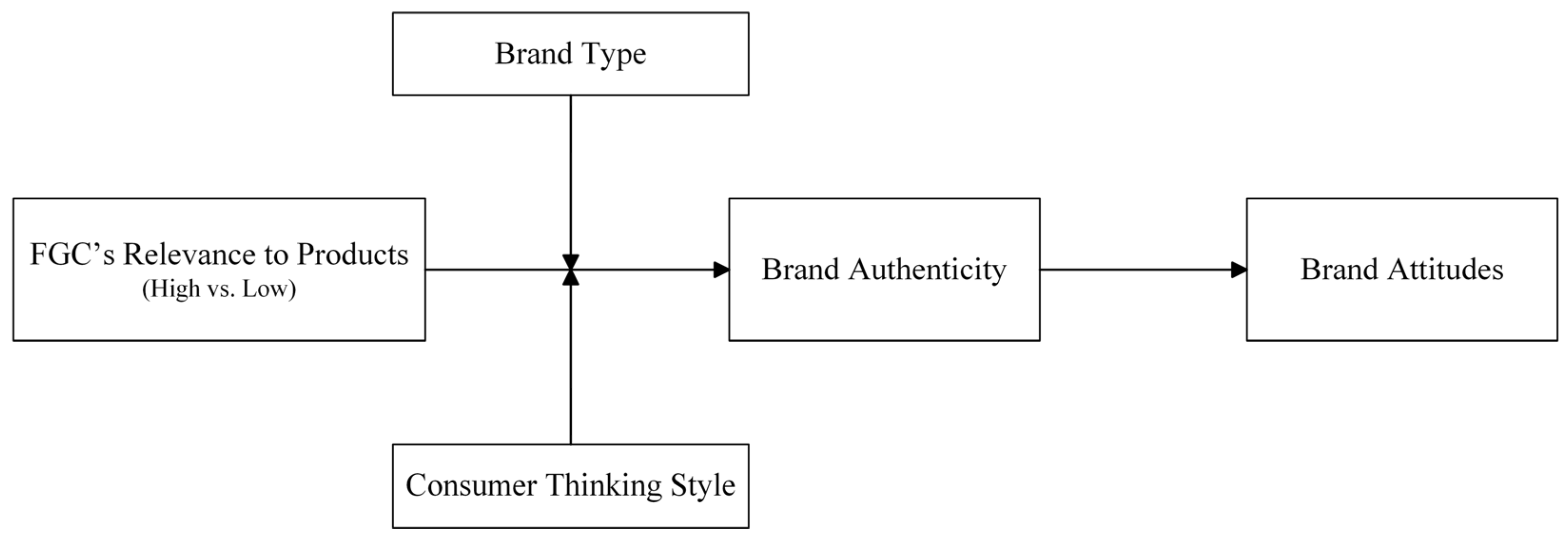

2.1. Impact of FGC’s Relevance to Products on Consumer Brand Attitudes

2.2. Mediating Role of Brand Authenticity

2.3. Moderating Role of Brand Type

2.4. Moderating Role of Consumer Thinking Style

3. Study 1

3.1. Design and Sample

3.2. Stimuli and Procedures

3.3. Results and Discussion

3.3.1. Manipulation Check

3.3.2. Main Effect

3.3.3. Discussion

4. Study 2

4.1. Design and Sample

4.2. Stimuli and Procedures

4.3. Results and Discussion

4.3.1. Manipulation Check

4.3.2. Main Effect

4.3.3. Mediating Effect

4.3.4. Discussion

5. Study 3

5.1. Design and Sample

5.2. Stimuli and Procedures

5.3. Results and Discussion

5.3.1. Manipulation Check

5.3.2. Main Effect

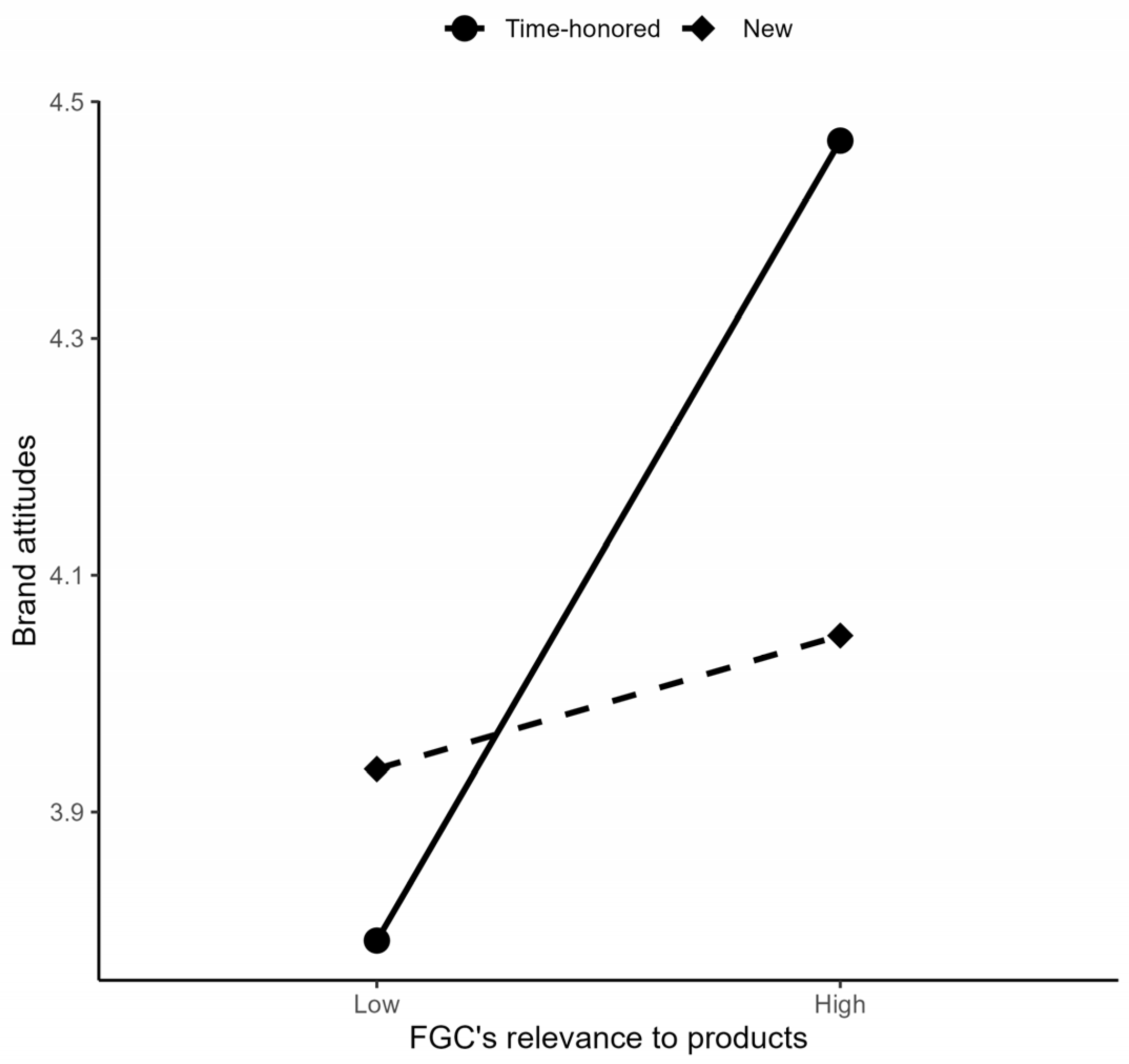

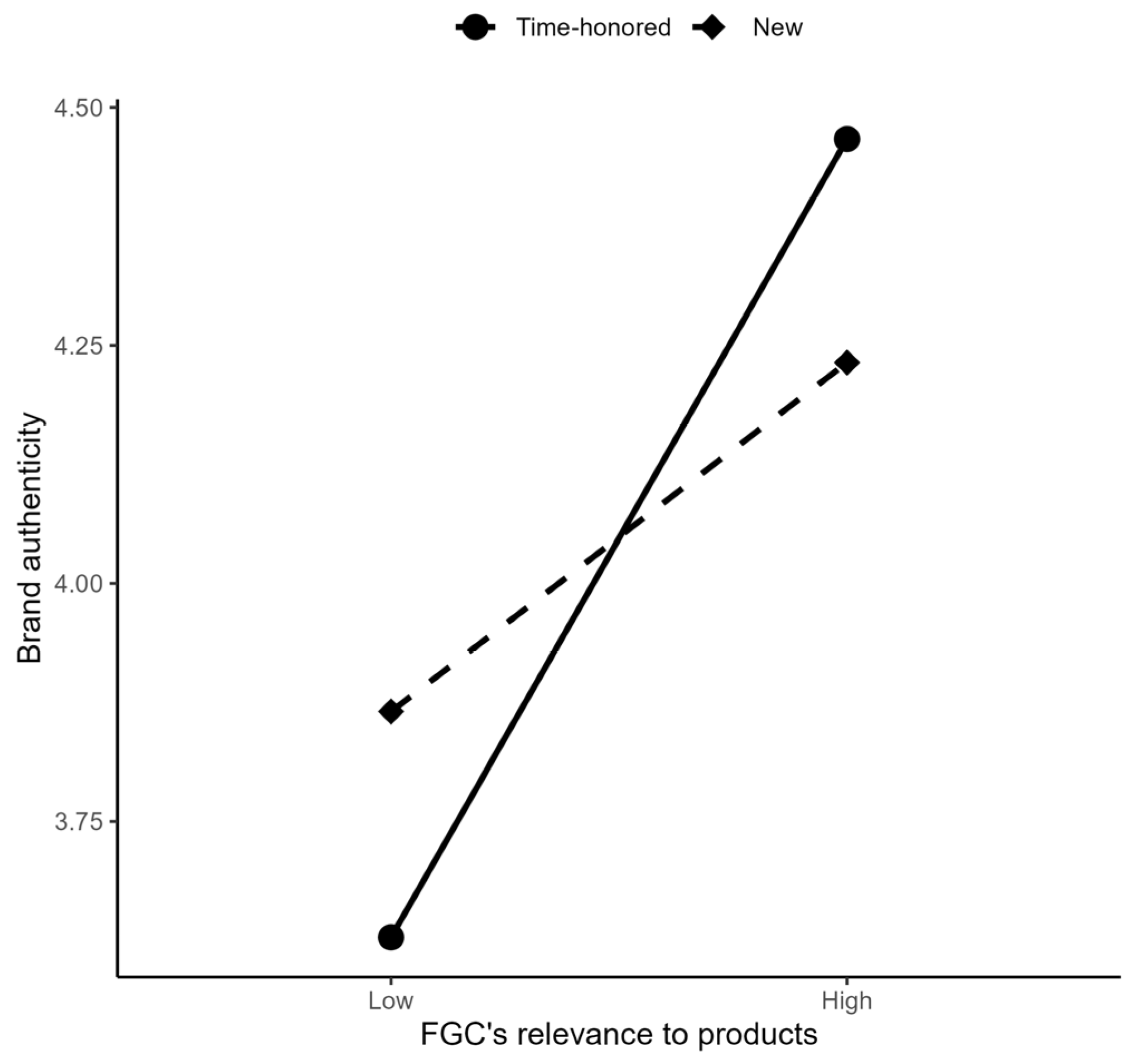

5.3.3. Moderating Effect of Brand Type

5.3.4. Discussion

6. Study 4

6.1. Design and Sample

6.2. Stimuli and Procedures

6.3. Results and Discussion

6.3.1. Manipulation Check

6.3.2. Main Effect

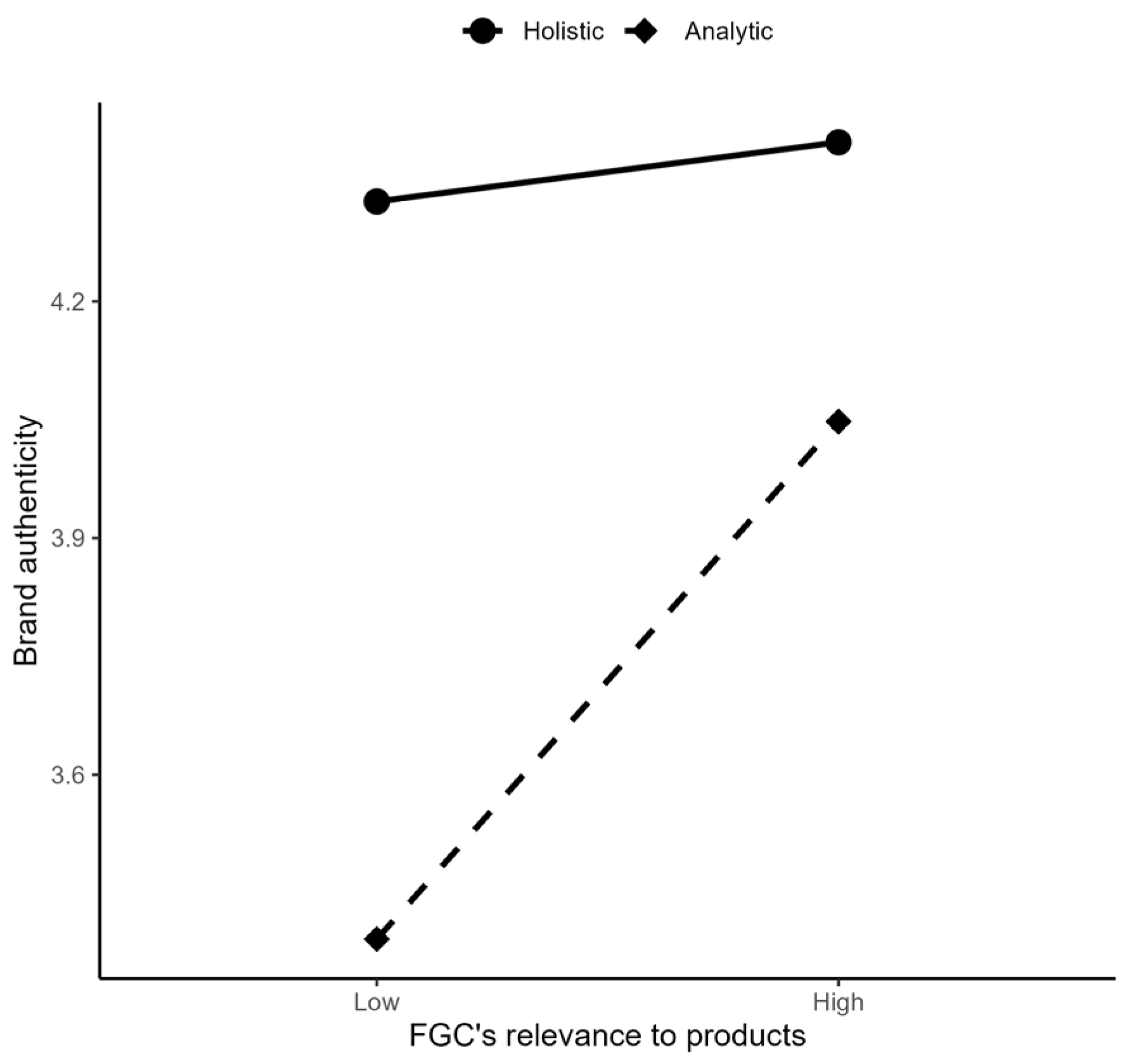

6.3.3. Moderating Effect of Consumer Thinking Style

6.3.4. Discussion

7. Discussion and Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Izogo, E.E.; Mpinganjira, M. Somewhat pushy but effective: The role of value-laden social media digital content marketing (VSM-DCM) for search and experience products. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. How the characteristics of social media influencers and live content influence consumers’ impulsive buying in live streaming commerce? The role of congruence and attachment. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial-What is an interactive marketing perspective and what are emerging research are-as? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Dinner, I.; Grewal, R. The ripple effect of firm-generated content on new movie releases. J. Mark. Res. 2023, 60, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I.; Căpușneanu, S.; Topor, D.I.; Tamas, A.S.; Solomon, A.-G.; Dănescu, T. Fundamental power of social media interactions for building a brand and customer relations. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1702–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Wu, B.; Zhou, L.; Chen, X. Order matters: Effect of use versus outreach order disclosure on persuasiveness of sponsored posts. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Wan, F. Differential effects of firm generated content on consumer digital engagement and firm performance: An outside-in perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 98, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Chan, K.W.; Kwon, J.; Dhaoui, C.; Septianto, F. Informational vs. emotional B2B firm-generated-content on social media engagement: Computerized visual and textual content analysis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 112, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Hosanagar, K.; Nair, H.S. Advertising content and consumer engagement on social media: Evidence from Facebook. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 5105–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meire, M.; Hewett, K.; Ballings, M.; Kumar, V.; Van den Poel, D. The role of marketer-generated content in customer engagement marketing. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaznezhad, H.; Dolan, R.; Rashidirad, M. The role of social media content format and platform in users’ engagement behavior. J. Interact. Mark. 2021, 53, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdallah, G.; Barzani, R.; Omar Dandis, A.; Eid, M.A.H. Social media marketing strategy: The impact of firm generated content on customer based brand equity in retail industry. J. Mark. Commun. 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J.; Borges-Tiago, M.T.; Tiago, F. Is firm-generated content a lost cause? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bezawada, R.; Rishika, R.; Janakiraman, R.; Kannan, P.K. From social to sale: The effects of firm-generated content in social media on customer behavior. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulis, A.; Rizomyliotis, I.; Konstantoulaki, K. Do firms still need to be social? Firm generated content in social media. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagci, M.I.; Biswas, A.; Dutta, S. Effects of comparative advertising format on consumer responses: The moderating effects of brand image and attribute relevance. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.; Jensen, T.; Burton, S.; Roach, D. The accuracy of brand and attribute judgments: The role of information relevancy, product experience, and attribute-relationship schemata. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, R.A.; Mohd Rashid, S.; Mohd Ishak, S.; Mohamad, B. Do firm-created contents on social media enhance brand equity and consumer response among consumers of automotive brands? J. Promot. Manag. 2020, 26, 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.K.T.; Tran, P.T.K.; Tran, V.T. The relationships among social media communication, brand equity and satisfaction in a tourism destination: The case of Danang city, Vietnam. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 1187–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetscherin, M.; Toncar, M.F. Valuating brand equity and product-related attributes in the context of the German automobile market. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 17, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial–The misassumptions about contributions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardes, F.R. Consumer inference: Determinants, consequences, and implications for advertising. In Advertising Exposure, Memory and Choice 1993; Mitchell, A.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 163–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kardes, F.R.; Posavac, S.S.; Cronley, M.L. Consumer inference: A review of processes, bases, and judgment contexts. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 230–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.J.; Hershfield, H.E. Consumers make different inferences and choices when product uncertainty is attributed to forgetting Rather than ignorance. J. Consum. Res. 2020, 47, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, R.S.; Schlosser, A.E.; Poor, M.; Xu, L. So close I can almost sense it: The interplay between sensory imagery and psychological distance. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardes, F.R.; Cronley, M.L.; Pontes, M.C.; Houghton, D.C. Down the garden path: The role of conditional inference processes in self-persuasion. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 11, 15968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Ye, C.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. Virtual ideality vs. virtual authenticity: Exploring the role of social signals in interactive marketing. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.-T.; Mai, N.Q.; Nguyen, L.T.; Thuan, N.H.; Dang-Pham, D.; Hoang, A.-P. Examining authenticity on digital touchpoint: A thematic and bibliometric review of 15 years’ literature. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulard, J.G.; Raggio, R.D.; Folse, J.A.G. Disentangling the meanings of brand authenticity: The entity-referent correspondence framework of authenticity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.; Baxter, S.M.; Kulczynski, A. Promoting authenticity through celebrity brands. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 2072–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiggle, S.; Nguyen, H.T.; Caravella, M. More than fit: Brand extension authenticity. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarah, T.; Bayram, P.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Elrehail, H. The role of brand interactivity and involvement in driving social media consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty: The mediating effect of brand trust. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, F.; Dwivedi, A.; Nayeem, T. Brand authenticity building effect of brand experience and downstream effects. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septianto, F.; Seo, Y.; Sung, B.; Zhao, F. Authenticity and exclusivity appeals in luxury advertising: The role of promotion and prevention pride. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 1305–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, B.; Zhou, L. The effect of image enhancement on influencer’s product recommendation effectiveness: The roles of perceived influencer authenticity and post type. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Gong, X.; Wang, J. Simple = Authentic: The effect of visually simple package design on perceived brand authenticity and brand choice. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 166, 114078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulard, J.G.; Raggio, R.D.; Folse, J.A.G. Brand authenticity: Testing the antecedents and outcomes of brand management’s passion for its products. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lude, M.; Prügl, R. Why the family business brand matters: Brand authenticity and the family firm trust inference. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Teran, C.; Battocchio, A.F.; Bertellotti, E.; Wrzesinski, S. Building Brand Authenticity on Social Media: The Impact of Instagram Ad Model Genuineness and Trustworthiness on Perceived Brand Authenticity and Consumer Responses. J. Interact. Advert. 2021, 21, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.H.; Hsieh, J.-K.; Kumar, S. Does the verified badge of social media matter? The perspective of trust transfer theory. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuhara, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Okada, M.; Kato, M.; Kiuchi, T. Designing persuasive health materials using processing fluency: A literature review. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, R.J. Psychological correlates of habitual diet in healthy adults. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 53–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, X. ‘New and old’: Consumer evaluations of co-branding between new brands and Chinese time-honored brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forêt, P.; Mazzalovo, G. The long march of the Chinese luxury industry towards globalization: Questioning the relevance of the ‘China time-honored brand’ label. Luxury 2014, 1, 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Prayag, G.; Song, H. The effects of consumer brand authenticity, brand image, and age on brand loyalty in time-honored restaurants: Findings from SEM and fsQCA. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-N.; Li, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-H.; Ruan, W.-Q. A study on China’s time-honored catering brands: Achieving new inheritance of traditional brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Li, Y.Q.; Liu, C.H.; Ruan, W.Q. How does authenticity enhance flow experience through perceived value and involvement: The moderating roles of innovation and cultural identity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 711–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, K.; Martinec, R. Consumer perceptions of iconicity and indexicality and their influence on assessments of authentic market offerings. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R.E.; Peng, K.; Choi, I.; Norenzayan, A. Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Nisbett, R.E.; Masuda, T. Culture and the physical environment: Holistic versus analytic perceptual affordances. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, D.; Gerrath, M.H.E.E.; Liu, Y.Y. How scarcity and thinking styles boost referral effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1928–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T. How cognitive style influences the mental accounting system: Role of analytic versus holistic thinking. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 45, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. Do negative consumption experiences hurt manufacturers or retailers? The influence of reasoning style on consumer blame attributions and purchase intention. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V.A.; Bearden, W.O. The effects of price on brand extension evaluations: The moderating role of extension similarity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A.; Olson, J.C. Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude? J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Dalal, R.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Park, H. Culture and judgment of causal relevance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Mieiro, S.; Huang, G. How social media advertising features influence consumption and sharing intentions: The mediation of customer engagement. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpenka, L.; Rudienė, E.; Morkunas, M.; Volkov, A. The influence of a brand’s visual content on consumer trust in social media community groups. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2424–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, C.L.; Donthu, N.; Yoo, B. Brand authenticity: Literature review, comprehensive definition, and an amalgamated scale. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2023, 31, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwani, L.; Cherry, A. A consumer perspective on brand authenticity: Insight into drivers and barriers. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2024, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, X.; Zhou, M. Impacts of brand digitalization on brand market performance: The mediating role of brand competence and brand warmth. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachvei, A.; Notta, O.; Koronaki, E. Effects of content characteristics on stages of customer engagement in social media: Investigating European wine brands. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharnouby, M.H.; Jayawardhena, C.; Liu, H.; Elbedweihy, A.M. Strengthening consumer–brand relationships through avatars. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.K.; McLelland, M.A.; Wallace, L.K. Brand avatars: Impact of social interaction on consumer–brand relationships. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.S.; Siddiqui, U.A.; Khan, M.A.; Alkandi, I.G.; Saxena, A.K.; Siddiqui, J.H. Creating electronic word of mouth credibility through social networking sites and determining its impact on brand image and online purchase intentions in India. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indirect Effect | Direct Effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Value | Standard Deviation | 95% Confidence Interval | Effect Value | Standard Deviation | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| FGC’s relevance to products → Brand authenticity → Brand attitudes | Time-honored brand | 0.6071 | 0.1304 | [0.3695, 0.8788] | −0.0427 | 0.0661 | [−0.1732, 0.0878] |

| New brand | 0.2654 | 0.1095 | [0.0457, 0.4823] | ||||

| Group difference | 0.3417 | 0.1773 | [0.0009, 0.6936] | ||||

| Study | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Brand Authenticity | SD | Brand Attitudes | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | High | — | — | — | 4.1736 | 0.6150 |

| Low | — | — | — | 3.9097 | 0.6292 | |

| Study 2 | High | — | 4.2833 | 0.4564 | 4.1667 | 0.6450 |

| Low | — | 4.0244 | 0.6599 | 3.8211 | 0.7996 | |

| Study 3 | High | Time-honored | 4.4667 | 0.3652 | 4.4670 | 0.3902 |

| High | New | 4.2319 | 0.5110 | 4.0489 | 0.7044 | |

| Low | Time-honored | 3.6279 | 1.1156 | 3.7907 | 0.8326 | |

| Low | New | 3.8652 | 0.9496 | 3.9362 | 0.7793 | |

| Study 4 | High | Analytic | 4.0476 | 0.7122 | 3.8968 | 0.7633 |

| High | Holistic | 4.4015 | 0.4103 | 4.1973 | 0.6664 | |

| Low | Analytic | 3.3913 | 1.0618 | 3.2826 | 1.0134 | |

| Low | Holistic | 4.3265 | 0.6955 | 4.3330 | 0.5615 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Z. How Does the Relevance of Firm-Generated Content to Products Affect Consumer Brand Attitudes? J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010019

Li Y, Yin Y, Wang Z. How Does the Relevance of Firm-Generated Content to Products Affect Consumer Brand Attitudes? Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yao, Ying Yin, and Zhiqiang Wang. 2025. "How Does the Relevance of Firm-Generated Content to Products Affect Consumer Brand Attitudes?" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010019

APA StyleLi, Y., Yin, Y., & Wang, Z. (2025). How Does the Relevance of Firm-Generated Content to Products Affect Consumer Brand Attitudes? Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20010019