Does Gender Matter for Electronic Word-of-Mouth Interactions in Social Media Marketing Strategies? An Empirical Multi-Sample Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

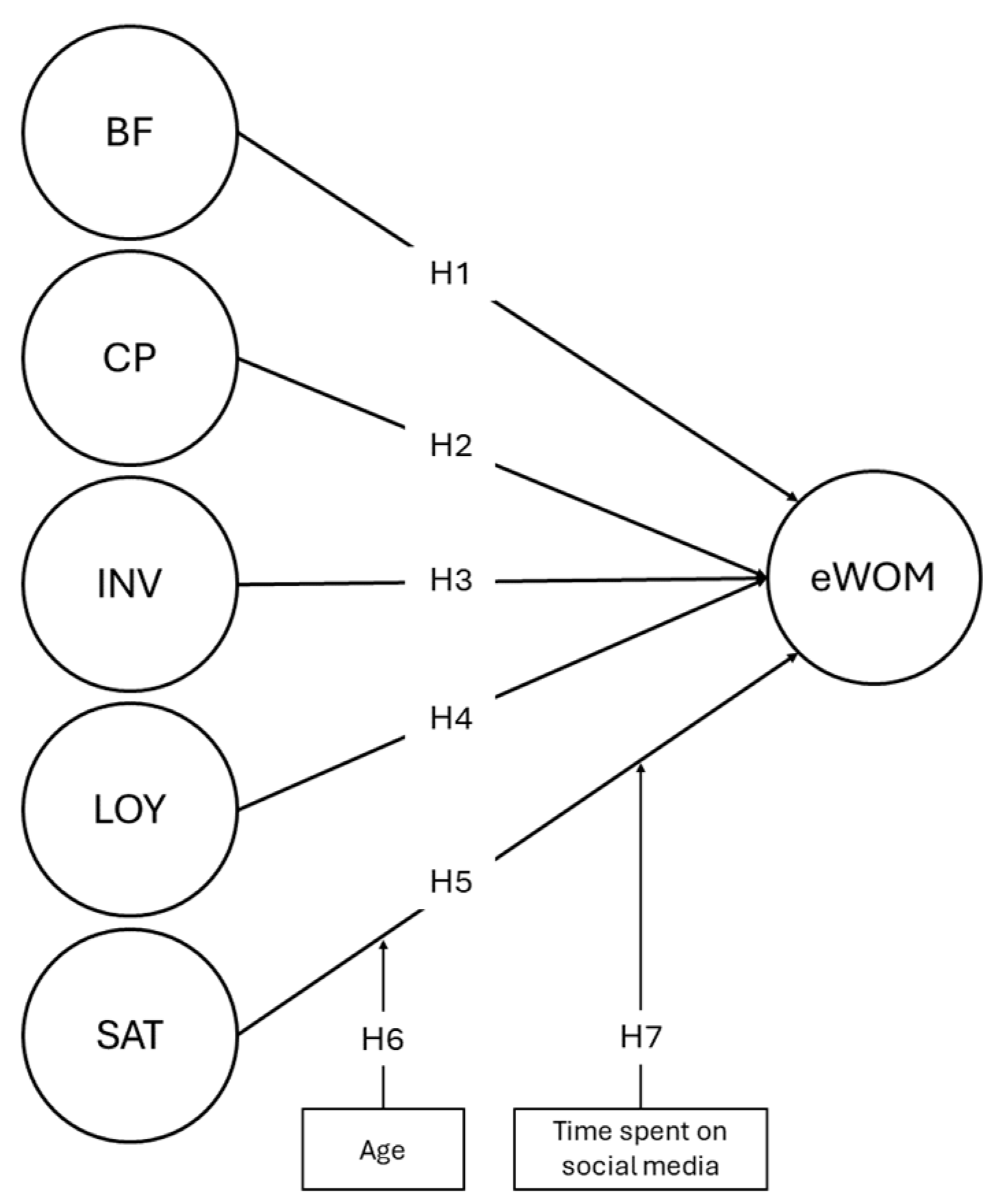

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Social Capital Theory

2.2. eWOM’s Strategic Importance in Social Media Settings

2.3. Hypotheses Development

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Measurement Models for Female and Male Samples of Respondents

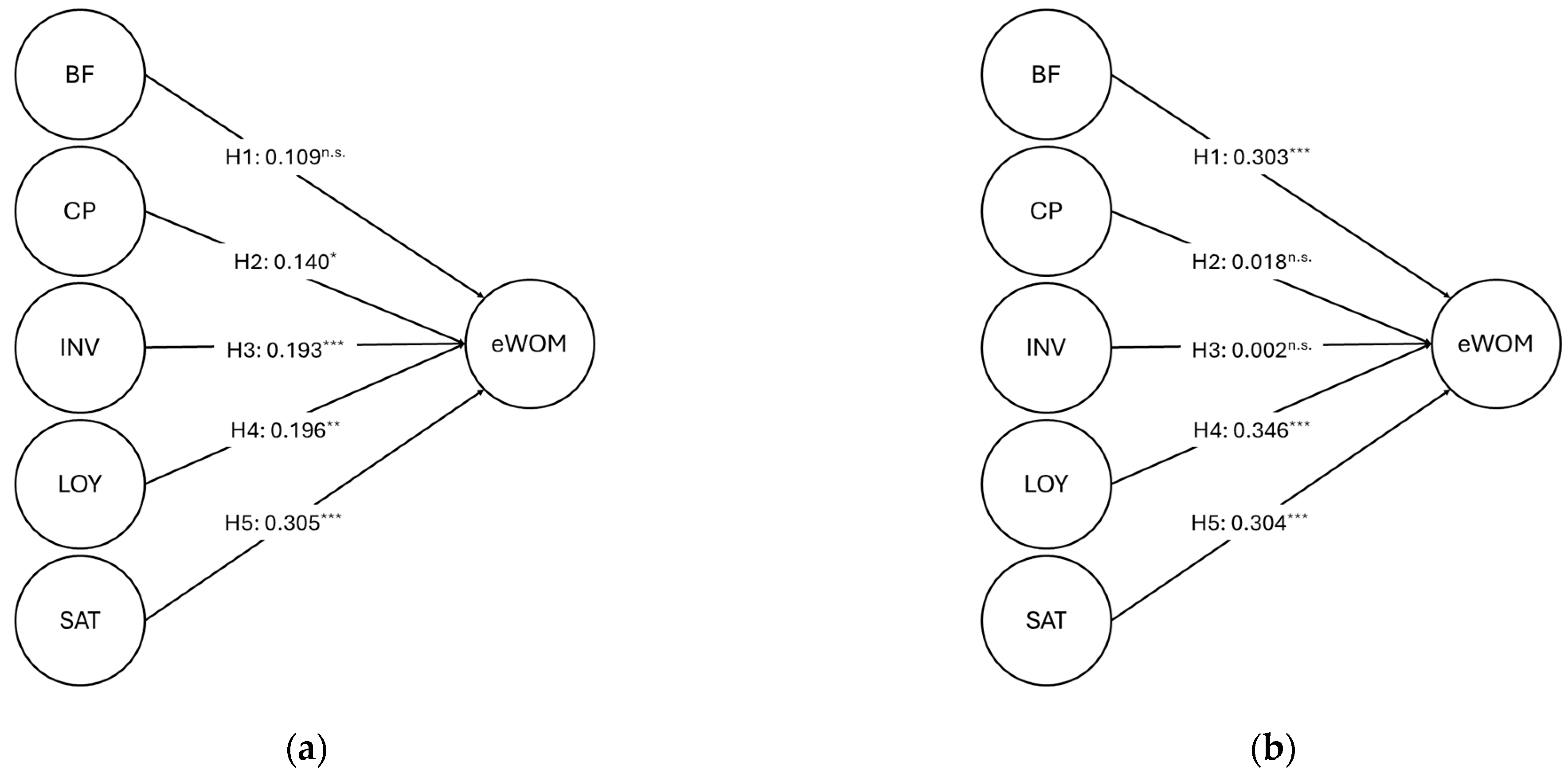

4.2. Hypothesis Testing of Direct Effects

4.3. Hypothesis Testing of Interaction Effects

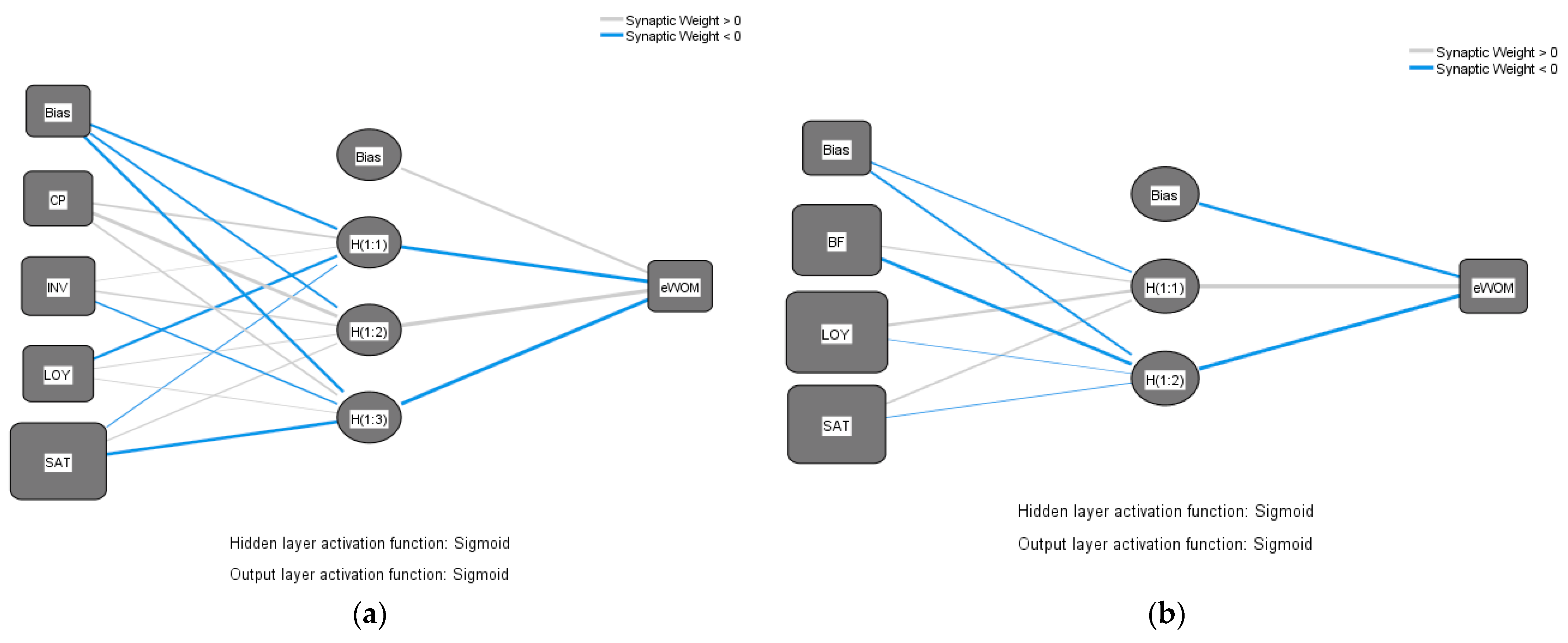

4.4. Artificial Neural Networks

5. Discussion of Results

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Scale Items and Sources | Female Sample | Male Sample | ||

| Loadings | VIF | Loadings | VIF | ||

| Brand Familiarity | (Source: Acharya [67]) | ||||

| BF1 | “I am familiar with this brand I like on Facebook” | 0.856 | 2.239 | 0.891 | 2.744 |

| BF2 | “I have experience with [brand]” | 0.884 | 2.608 | 0.881 | 2.955 |

| BF3 | “I am knowledgeable about [brand]” | 0.859 | 2.581 | 0.896 | 3.039 |

| BF4 | “I easily observe [brand] on social media” | 0.875 | 2.610 | 0.814 | 2.011 |

| Customer Participation | (Source: Casaló et al. [68]; Kamboj et al. [69]; Phan Tan [47]) | ||||

| CP1 | “I actively participate in brand-related activities on Facebook”. | 0.903 | 1.727 | 0.885 | 1.496 |

| CP2 | “In general, I frequently and with great passion write remarks on Facebook about this brand”. | 0.913 | 1.727 | 0.891 | 1.496 |

| Involvement | (Source: Chen [70]; Vinerean and Opreana [71]) | ||||

| INV1 | “[brand] is a valuable part of my social media experience on Facebook” | 0.868 | 2.139 | 0.879 | 2.116 |

| INV2 | “I’m very motivated to buy [brand]”. | 0.904 | 2.499 | 0.892 | 2.303 |

| INV3 | “It is very important that I buy this brand that I like on Facebook”. | 0.898 | 2.295 | 0.890 | 2.286 |

| Customer Loyalty | (Source: Zeithaml et al. [72]; Rialti et al. [14]; Vinerean and Opreana[71]) | ||||

| LOY1 | “For me, [brand] is the best alternative”. | 0.831 | 2.298 | 0.849 | 2.482 |

| LOY2 | “I will buy [brand] regularly”. | 0.833 | 2.116 | 0.850 | 2.573 |

| LOY3 | “I intend to buy this brand in the near future”. | 0.810 | 1.929 | 0.868 | 3.447 |

| LOY4 | “When I need to purchase, [brand] is my best choice”. | 0.805 | 2.034 | 0.806 | 2.673 |

| LOY5 | “I’m proud to tell my family and friends that I have purchased this brand”. | 0.783 | 1.979 | 0.789 | 2.292 |

| Customer Satisfaction | (Source: Ruiz-Alba [15]; Rialti et al.[14]) | ||||

| SAT1 | “[brand] always fulfills my expectations”. | 0.879 | 2.165 | 0.853 | 2.070 |

| SAT2 | “I am delighted with [brand]”. | 0.881 | 2.193 | 0.908 | 2.374 |

| SAT3 | “I am generally happy with this brand”. | 0.902 | 2.388 | 0.896 | 2.273 |

| eWOM on Social Media | (Source: Moisescu et al. [5]; Phan Tan [47]; Choi et al. [73]) | ||||

| eWOM1 | “I recommend this brand to my friends on Facebook”. | 0.872 | 2.434 | 0.864 | 2.263 |

| eWOM2 | “I spread good words on social media about this brand”. | 0.877 | 2.421 | 0.830 | 2.110 |

| eWOM3 | “I am willing to share positive information about [brand] with others through Facebook”. | 0.849 | 2.226 | 0.871 | 2.501 |

| eWOM4 | “If my friends were looking to buy this type of product (associated with this brand), I would tell them to try this brand on social media”. | 0.850 | 2.127 | 0.842 | 2.035 |

References

- Statista. Number of Internet and Social Media Users Worldwide as of October 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Statista. Social Media Advertising-Worldwide. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/amo/advertising/social-media-advertising/worldwide (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Statista. Most Popular Social Networks Worldwide as of January 2024, Ranked by Number of Monthly Active Users (in Millions). 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Abbasi, A.Z.; Tsiotsou, R.H.; Hussain, K.; Rather, R.A.; Ting, D.H. Investigating the impact of social media images’ value, consumer engagement, and involvement on eWOM of a tourism destination: A transmittal mediation approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisescu, O.I.; Gică, O.A.; Herle, F.A. Boosting eWOM through social media brand page engagement: The mediating role of self-brand connection. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baykal, B.; Hesapci Karaca, O. Recommendation matters: How does your social capital engage you in eWOM? J. Consum. Mark. 2022, 39, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Lin, Z.; Pino, G.; Alguezaui, S.; Inversini, A. The role of visual cues in eWOM on consumers’ behavioral intention and decisions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, S.; Prentice, C.; Tsou, A.; Weeks, C.; Tam, L.; Luck, E. Managing eWOM for hotel performance. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2022, 32, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourjahanshahi, F.; Mollahosseini, A.; Dehyadegari, S. Website quality and users’ intention to use digital libraries: Examining users’ attitudes, online co-creation experiences, and eWOM. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhu, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y. Beyond weekdays: The impact of the weekend effect on eWOM of hedonic product. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Castro, A. Understanding drivers and outcomes of lurking vs. posting engagement behaviours in social media-based brand communities. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 660–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismagilova, E.; Rana, N.P.; Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. A meta-analysis of the factors affecting eWOM providing behaviour. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 1067–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialti, R.; Zollo, L.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Ciappei, C. Exploring the Antecedents of Brand Loyalty and Electronic Word of Mouth in Social-Media-Based Brand Communities: Do Gender Differences Matter? J. Glob. Mark. 2017, 30, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Alba, J.L.; Abou-Foul, M.; Nazarian, A.; Foroudi, P. Digital platforms: Customer satisfaction, eWOM and the moderating role of perceived technological innovativeness. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 2470–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, A.; Krampe, C. Why he buys it and she doesn’t–Exploring self-reported and neural gender differences in the perception of eCommerce websites. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kol, O.; Levy, S. Men on a mission, women on a journey-Gender differences in consumer information search behavior via SNS: The perceived value perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro-Sosa, G.; Moliner-Velázquez, B.; Gil-Saura, I.; Fuentes-Blasco, M. Influence of Electronic Word-Of-Mouth on Restaurant Choice Decisions: Does It Depend on Gender in the Millennial Generation? J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnoor, A.; Tiberius, V.; Atiyah, A.G.; Khaw, K.W.; Yin, T.S.; Chew, X.; Abbas, S. How positive and negative electronic word of mouth (eWOM) affects customers’ intention to use social commerce? A dual-stage multi group-SEM and ANN analysis. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 808–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, B.; Moore Koskie, M.; Locander, W. How electronic word of mouth (eWOM) shapes consumer social media shopping. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 1002–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorie, A.; Loranger, D. Word on the street: Apparel-related critical incidents leading to eWOM and channel behaviour among millennial and Gen Z consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 2024, 41, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martín, S.; Prodanova, J.; Jiménez, N. The impact of age in the generation of satisfaction and WOM in mobile shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.E.K. The impact of restaurant service experience valence and purchase involvement on consumer motivation and intention to engage in eWOM. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 18, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkedder, N.; Özata, F.Z. I will buy virtual goods if I like them: A hybrid PLS-SEM-artificial neural network (ANN) analytical approach. J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 12, 42–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. An SEM-neural network approach for predicting antecedents of online grocery shopping acceptance. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 1723–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, D.T.V.; Mai, L.T.V.; Dang, T.-Q.; Le, T.-T.; Nguyen, L.-T. Unlocking impulsive buying behavior in the metaverse commerce: A combined analysis using PLS-SEM and ANN. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkedder, N.; Bakır, M. A hybrid analysis of consumer preference for domestic products: Combining PLS-SEM and ANN approaches. J. Glob. Mark. 2023, 36, 372–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armutcu, B.; Ramadani, V.; Tan, A.; Appolloni, A. Understanding the Role of Consumers for a Sustainable Future: Empirical Evidence from a Three-Stage Hybrid Analysis Incorporating Bibliometrics, PLS-SEM, and ANN. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 2065–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yeh, R.K.-J.; Chen, C.; Tsydypov, Z. What drives electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites? Perspectives of social capital and self-determination. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, E. How word-of-mouth advertising works. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1966, 44, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.W.; Sanders, G.L.; Moon, J. Exploring the effect of e-WOM participation on e-Loyalty in e-commerce. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Ruiz, C.; Curras-Perez, R. How consumers process online review types in familiar versus unfamiliar destinations. A self-reported and neuroscientific study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 199, 123067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Satish, S.M. eWOM: Extant research review and future research avenues. Vikalpa 2016, 41, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Cantallops, A.; Ramon-Cardona, J.; Salvi, F. The impact of positive emotional experiences on eWOM generation and loyalty. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2018, 22, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Wu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L. How differences in eWOM platforms impact consumers’ perceptions and decision-making. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2018, 28, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.S.; Siddiqui, U.A.; Khan, M.A.; Alkandi, I.G.; Saxena, A.K.; Siddiqui, J.H. Creating Electronic Word of Mouth Credibility through Social Networking Sites and Determining Its Impact on Brand Image and Online Purchase Intentions in India. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Gorgus, T.; Kaufmann, H.R. Antecedents and outcomes of online brand engagement: The role of brand love on enhancing electronic-word-of-mouth. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, S.A.; Araujo, T.; Bernritter, S.F.; van Noort, G. Seeing the wood for the trees: How machine learning can help firms in identifying relevant electronic word-of-mouth in social media. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Featherman, M.; Brooks, S.L.; Hajli, N. Exploring Gender Differences in Online Consumer Purchase Decision Making: An Online Product Presentation Perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 21, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Foscht, T.; Kerschbaumer, R.H.; Eisingerich, A.B. “Pulling back the curtain”: Company tours as a customer education tool and effects on pro-brand behaviors. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinska-Krakowiak, M. Women are more likely to buy unknown brands than men: The effects of gender and known versus unknown brands on purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.; Baek, M.; Jang, H.; Sung, S. Storyscaping in fashion brand using commitment and nostalgia based on ASMR marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.Y.; Perks, H. Effects of consumer perceptions of brand experience on the web: Brand familiarity, satisfaction and brand trust. J. Consum. Behav. 2005, 4, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Mannan, M. Consumer online purchase behavior of local fashion clothing brands. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, B.A. A Model of Group Satisfaction in Computer-Mediated Communication and Face-To-Face Meetings. Behav. Inf. Technol. 1996, 15, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan Tan, L. Customer participation, positive electronic word-of-mouth intention and repurchase intention: The mediation effect of online brand community trust. J. Mark. Commun. 2023, 30, 792–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Rahman, S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Wyllie, J.; Voola, R. Engaging gen Y customers in online brand communities: A cross-national assessment. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, S.; Gallego, M.D. eWOM in C2C Platforms: Combining IAM and Customer Satisfaction to Examine the Impact on Purchase Intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1612–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.L.H. The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhidari, A.; Iyer, P.; Paswan, A. Personal level antecedents of eWOM and purchase intention, on social networking sites. J. Cust. Behav. 2015, 14, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, H.; Bal, V. Analysis of the Effect of Quality Components of Web 2.0 Enabled E Commerce Websites on Electronic Word of Mouth Marketing (E WOM) and on Customer Loyalty. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. 2016, 25, 979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Son, J.E.; Kim, H.W.; Jang, Y.J. Investigating Factors Affecting Electronic Word-of-Mouth in the Open Market Context: A Mixed Methods Approach.16th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, PACIS 2012, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. 167. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2012/167 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Khan, M.F.; Amin, F.; Jan, A.; Hakak, I.A. Social media marketing activities in the Indian airlines: Brand equity and electronic word of mouth. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Sousa, A.; Borges, A.P.; Matos Graça Ramos, P. Understanding masstige wine brands’ potential for consumer-brand relationships. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2024, 36, 918–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelen, J.; Özturan, P.; Verlegh, P.W. The differential impact of brand loyalty on traditional and online word of mouth: The moderating roles of self-brand connection and the desire to help the brand. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2017, 34, 872–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.; Lee, M. The joint effects of compensation frames and price levels on service recovery of online pricing error. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2012, 22, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner-Velázquez, B.; Ruiz-Molina, M.-E.; Fayos-Gardó, T. Satisfaction with service recovery: Moderating effect of age in word-of-mouth. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzam, J. The moderating role of age on social media marketing activities and customer brand engagement on Instagram social network. Young Consum. 2022, 23, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj Khalifa, A. What motivates consumers to communicate eWOM: Evidence from Tunisian context. J. Strateg. Mark. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Jianqiu, Z.; Dukhaykh, S.; Fan, M.; Trunk, A. Understanding the effects of eWOM antecedents on online purchase intention in China. Information 2021, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Dewani, P.P.; Behl, A.; Pereira, V.; Dwivedi, Y.; Del Giudice, M. A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of eWOM credibility: Investigation of moderating role of culture and platform type. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehm, K.E.; Feder, K.A.; Tormohlen, K.N.; Crum, R.M.; Young, A.S.; Green, K.M.; Pacek, L.R.; La Flair, L.N.; Mojtabai, R. Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Kamper-DeMarco, K.E.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Dong, D.; Xue, P. Time Spent on Social Media and Risk of Depression in Adolescents: A Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A. The impact of brand familiarity, customer brand engagement and self-identification on word-of-mouth. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2021, 10, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.; Flavián, C.; Guinaliu, M. The impact of participation in virtual brand communities on consumer trust and loyalty: The case of free software. Online Inf. Rev. 2007, 31, 775–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Sarmah, B.; Gupta, S.; Dwivedi, Y. Examining branding co-creation in brand communities on social media: Applying the paradigm of Stimulus-Organism-Response. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C. The customer satisfaction–loyalty relation in an interactive e-service setting: The mediators. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2012, 19, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Opreana, A. Measuring Customer Engagement in Social Media Marketing: A Higher-Order Model. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2633–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Thoeni, A.; Kroff, M.W. Brand Actions on Social Media: Direct Effects on Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) and Moderating Effects of Brand Loyalty and Social Media Usage Intensity. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2018, 17, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, T.G.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781544396408. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4; SmartPLS GmbH: Oststeinbek, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J.-M.; Cheah, J.H.; Gholamzade, R.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM’s Most Wanted Guidance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinić, Z.; Marinković, V.; Djordjevic, A.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. What drives customer satisfaction and word of mouth in mobile commerce services? A UTAUT2-based analytical approach. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 33, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinic, Z.; Marinkovic, V.; Molinillo, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. A multi-analytical approach to peer-to-peer mobile payment acceptance prediction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinić, Z.; Marinković, V.; Kalinić, L.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Neural network modeling of consumer satisfaction in mobile commerce: An empirical analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 175, 114803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.-H.; Hew, J.-J.; Leong, L.-Y.; Wei-Han Tan, G.; Ooi, K.-B. Wearable payment: A deep learning-based dual-stage SEM-ANN analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 157, 113477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Marinković, V.; Kalinić, Z. A SEM-neural network approach for predicting antecedents of m-commerce acceptance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, I.; Karatas, K.; Kusci, I.; Al-Emran, M. Understanding the social sustainability of the Metaverse by integrating UTAUT2 and big five personality traits: A hybrid SEM-ANN approach. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Ooi, K.-B.; Chong, A.Y.-L. Predicting the antecedents of trust in social commerce–A hybrid structural equation modeling with neural network approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Meseguer-Artola, A. A PLS-neural network analysis of motivational orientations leading to Facebook engagement and the moderating roles of flow and age. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Tan, G.W.H.; Yuan, Y.; Ooi, K.B.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Revisiting TAM2 in behavioral targeting advertising: A deep learning-based dual-stage SEM-ANN analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Lee, T. Gender differences in consumers’ perception of online consumer reviews. Electron. Commer. Res. 2011, 11, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann, A.; Chen, Q. Better than sex: Further development and validation of the consumption gender scale. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, M.; Burki, U.; Ali, R.; Dahlstrom, R. Systematic review of gender differences and similarities in online consumers’ shopping behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2022, 39, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.S. Gender Similarities and Differences. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancillai, C.; Bartoloni, S.; Filipovic, J.; Temperini, V. The role of online communities in shaping the Society 5.0 paradigm: A social capital perspective. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha (>0.7) | Composite Reliability (CR > 0.7) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE > 0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sample | BF | 0.892 | 0.895 | 0.754 |

| CP | 0.787 | 0.788 | 0.824 | |

| INV | 0.869 | 0.874 | 0.792 | |

| LOY | 0.872 | 0.878 | 0.660 | |

| SAT | 0.865 | 0.867 | 0.788 | |

| eWOM | 0.885 | 0.887 | 0.743 | |

| Male sample | BF | 0.893 | 0.896 | 0.759 |

| CP | 0.731 | 0.731 | 0.788 | |

| INV | 0.865 | 0.865 | 0.787 | |

| LOY | 0.890 | 0.903 | 0.694 | |

| SAT | 0.864 | 0.880 | 0.785 | |

| eWOM | 0.874 | 0.878 | 0.726 |

| Sample | BF | CP | INV | LOY | SAT | eWOM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sample | BF | ||||||

| CP | 0.614 | ||||||

| INV | 0.649 | 0.591 | |||||

| LOY | 0.64 | 0.629 | 0.807 | ||||

| SAT | 0.692 | 0.612 | 0.74 | 0.788 | |||

| eWOM | 0.658 | 0.654 | 0.747 | 0.76 | 0.799 | ||

| Male sample | BF | ||||||

| CP | 0.647 | ||||||

| INV | 0.542 | 0.599 | |||||

| LOY | 0.515 | 0.697 | 0.850 | ||||

| SAT | 0.612 | 0.73 | 0.698 | 0.698 | |||

| eWOM | 0.72 | 0.683 | 0.69 | 0.762 | 0.787 |

| Sample | Hypothesis | Path Coefficients | 2.50% 1 | 97.50% 1 | St. dev. | T-Statistics | f-Square | p-Values | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sample | H1a: BF -> eWOM | 0.109 | 0.003 | 0.223 | 0.056 | 1.954 | 0.017 | 0.051 | Reject |

| H2a: CP -> eWOM | 0.140 | 0.031 | 0.247 | 0.055 | 2.521 | 0.032 | 0.012 | Accept | |

| H3a: INV -> eWOM | 0.193 | 0.077 | 0.314 | 0.061 | 3.18 | 0.042 | 0.001 | Accept | |

| H4a: LOY -> eWOM | 0.196 | 0.052 | 0.327 | 0.070 | 2.801 | 0.039 | 0.005 | Accept | |

| H5a: SAT -> eWOM | 0.305 | 0.171 | 0.438 | 0.069 | 4.445 | 0.103 | 0.000 | Accept | |

| Male sample | H1b: BF -> eWOM | 0.303 | 0.155 | 0.428 | 0.069 | 4.395 | 0.165 | 0.000 | Accept |

| H2b: CP -> eWOM | 0.018 | −0.119 | 0.15 | 0.069 | 0.255 | 0.000 | 0.799 | Reject | |

| H3b: INV -> eWOM | 0.002 | −0.166 | 0.215 | 0.098 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.982 | Reject | |

| H4b: LOY -> eWOM | 0.346 | 0.116 | 0.52 | 0.102 | 3.377 | 0.128 | 0.001 | Accept | |

| H5b: SAT -> eWOM | 0.304 | 0.159 | 0.463 | 0.077 | 3.935 | 0.126 | 0.000 | Accept |

| Sample | Hypothesis | Path Coefficients | 2.50% | 97.50% | St. dev. | T-Statistics | p-Values | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sample | TimeSpent × SAT -> eWOM | 0.007 | −0.057 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.223 | 0.823 | Reject |

| Age × SAT -> eWOM | −0.075 | −0.145 | −0.008 | 0.035 | 2.151 | 0.032 | Accept | |

| Male sample | TimeSpent × SAT -> eWOM | −0.013 | −0.152 | 0.135 | 0.073 | 0.183 | 0.855 | Reject |

| Age × SAT -> eWOM | 0.069 | −0.051 | 0.206 | 0.065 | 1.055 | 0.292 | Reject |

| ANN | Female Sample | Male Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-Square Average: | 0.6054 | R-Square Average: | 0.6721 | |

| Training RMSE | Testing RMSE | Training RMSE | Testing RMSE | |

| 1 | 0.094 | 0.091 | 0.093 | 0.094 |

| 2 | 0.094 | 0.093 | 0.107 | 0.090 |

| 3 | 0.098 | 0.083 | 0.093 | 0.083 |

| 4 | 0.098 | 0.118 | 0.093 | 0.064 |

| 5 | 0.099 | 0.087 | 0.087 | 0.068 |

| 6 | 0.103 | 0.074 | 0.090 | 0.102 |

| 7 | 0.095 | 0.084 | 0.092 | 0.071 |

| 8 | 0.092 | 0.122 | 0.094 | 0.115 |

| 9 | 0.096 | 0.094 | 0.086 | 0.045 |

| 10 | 0.092 | 0.088 | 0.098 | 0.064 |

| Average | 0.096 | 0.093 | 0.093 | 0.080 |

| St. deviation | 0.003 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.021 |

| ANN | Female Sample | Male Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | INV | LOY | SAT | BF | LOY | SAT | |

| 1 | 0.203 | 0.229 | 0.213 | 0.355 | 0.275 | 0.474 | 0.251 |

| 2 | 0.210 | 0.269 | 0.212 | 0.309 | 0.379 | 0.322 | 0.299 |

| 3 | 0.199 | 0.258 | 0.266 | 0.276 | 0.160 | 0.572 | 0.268 |

| 4 | 0.207 | 0.211 | 0.229 | 0.353 | 0.294 | 0.363 | 0.343 |

| 5 | 0.180 | 0.226 | 0.318 | 0.277 | 0.401 | 0.365 | 0.234 |

| 6 | 0.206 | 0.170 | 0.350 | 0.275 | 0.229 | 0.461 | 0.310 |

| 7 | 0.162 | 0.235 | 0.262 | 0.341 | 0.241 | 0.397 | 0.362 |

| 8 | 0.163 | 0.237 | 0.251 | 0.349 | 0.421 | 0.303 | 0.276 |

| 9 | 0.199 | 0.278 | 0.196 | 0.327 | 0.392 | 0.356 | 0.253 |

| 10 | 0.200 | 0.193 | 0.270 | 0.336 | 0.307 | 0.396 | 0.298 |

| Average | 0.193 | 0.231 | 0.257 | 0.320 | 0.310 | 0.401 | 0.289 |

| Normalized importance | 58.57% | 70.37% | 77.87% | 96.56% | 75.47% | 93.87% | 69.55% |

| Sample | Examined Driver of eWOM | Path Coefficient | ANN Result—Normalized Importance | PLS-SEM Ranking | ANN Ranking | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sample | CP | 0.140 | 58.57% | 4 | 4 | Matched |

| INV | 0.193 | 70.37% | 3 | 3 | ||

| LOY | 0.196 | 77.87% | 2 | 2 | ||

| SAT | 0.305 | 96.56% | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male sample | BF | 0.303 | 75.47% | 3 | 2 | Partially matched |

| LOY | 0.346 | 93.87% | 1 | 1 | ||

| SAT | 0.304 | 69.55% | 2 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vinerean, S.; Opreana, A.; Budac, C.; Mihaiu, D.M. Does Gender Matter for Electronic Word-of-Mouth Interactions in Social Media Marketing Strategies? An Empirical Multi-Sample Approach. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020079

Vinerean S, Opreana A, Budac C, Mihaiu DM. Does Gender Matter for Electronic Word-of-Mouth Interactions in Social Media Marketing Strategies? An Empirical Multi-Sample Approach. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(2):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020079

Chicago/Turabian StyleVinerean, Simona, Alin Opreana, Camelia Budac, and Diana Marieta Mihaiu. 2025. "Does Gender Matter for Electronic Word-of-Mouth Interactions in Social Media Marketing Strategies? An Empirical Multi-Sample Approach" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 2: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020079

APA StyleVinerean, S., Opreana, A., Budac, C., & Mihaiu, D. M. (2025). Does Gender Matter for Electronic Word-of-Mouth Interactions in Social Media Marketing Strategies? An Empirical Multi-Sample Approach. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(2), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020079