Medicinal Plants, Phytochemicals, and Herbs to Combat Viral Pathogens Including SARS-CoV-2

Abstract

1. Introduction

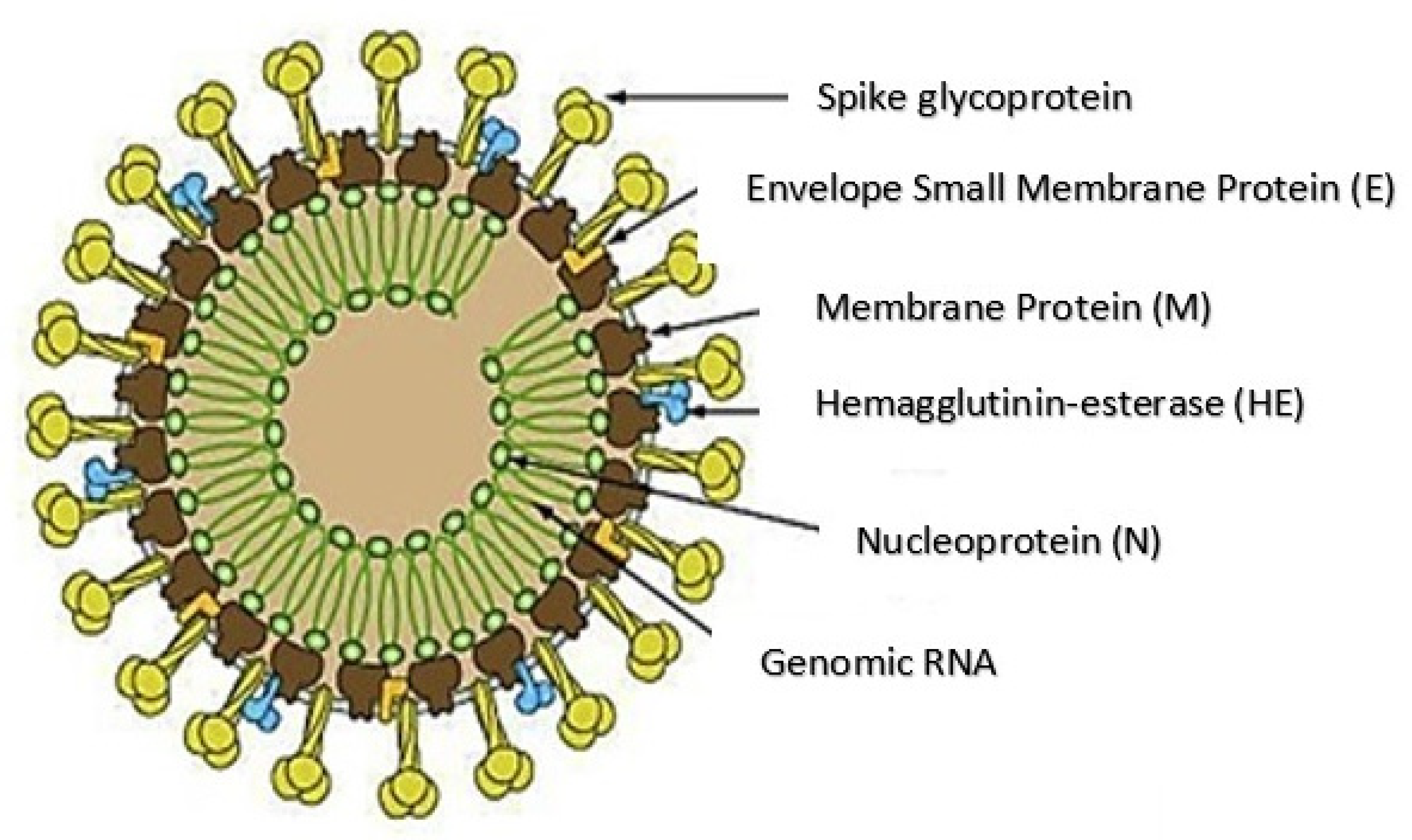

2. Structure and Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2

3. Similarities of Viruses to SARS COV-2

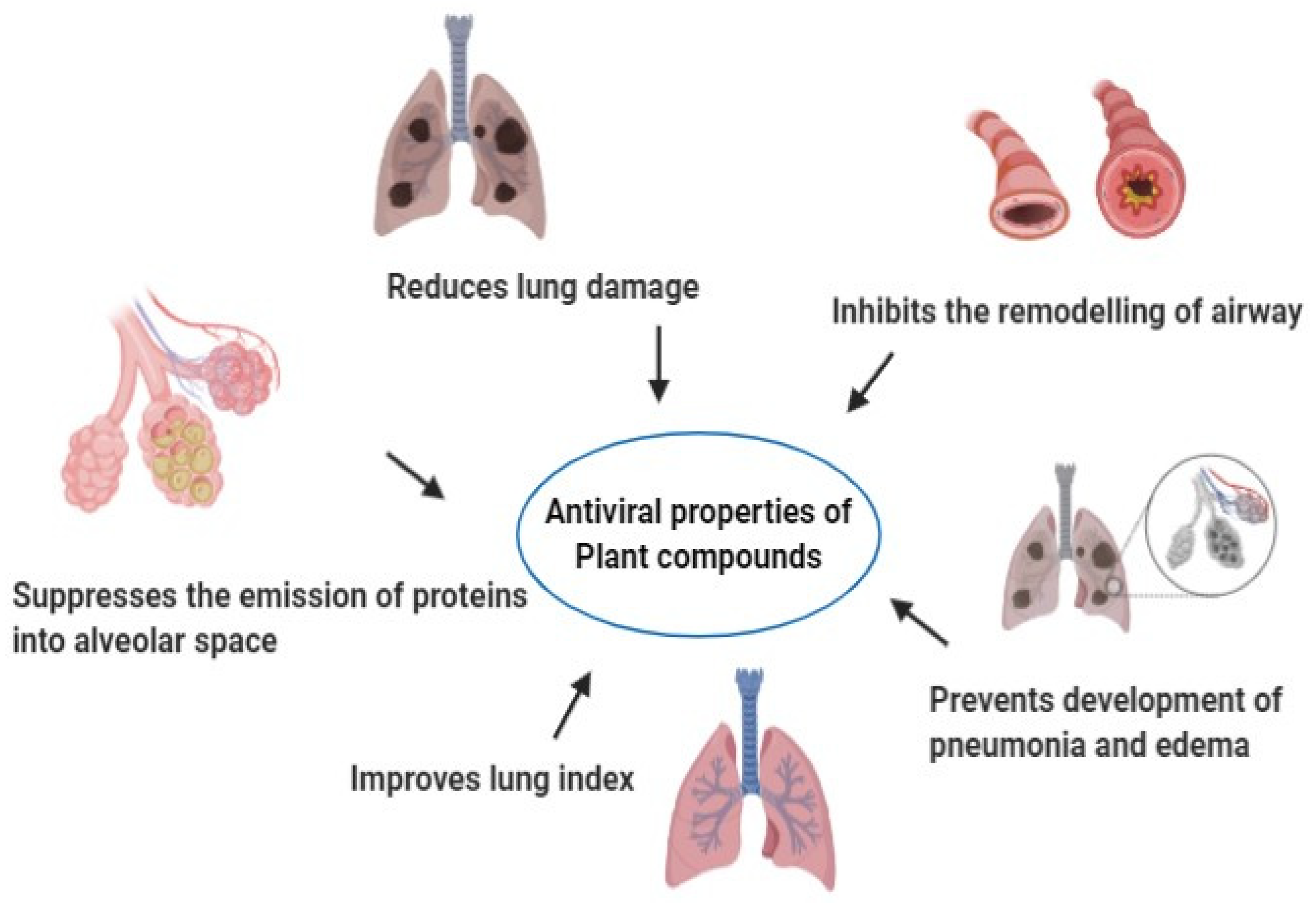

4. Plants with Antiviral Properties

5. Plants of Indian Origin and Common Use

6. Plant-Specific Compounds and Antiviral Mechanisms

6.1. Flavonoids

6.2. Catechins

6.3. Quercetin

6.4. Apigenin and Baicalin

6.5. Luteolin

6.6. Kaempferol

6.7. Alkaloids

6.8. Saponins

6.9. Lignans

6.10. Tannins

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclosure Statement

References

- Dhama, K.; Khan, S.; Tiwari, R.; Sircar, S.; Bhat, S.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, K.P.; Chaicumpa, W.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Coronavirus disease 2019-COVID-19. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00028-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanouz, I.; Belhassan, A.; El-Khatabi, K.; Lakhlifi, T.; El-Ldrissi, M.; Bouachrine, M. Moroccan Medicinal plants as inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Computational investigations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divya, M.; Vijayakumar, S.; Chen, J.; Vaseeharan, B.; Durán-Lara, E.F. A review of South Indian medicinal plant has the ability to combat against deadly viruses along with COVID-19? Microb. Pathog. 2020, 104277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, I.; Onay, A. Potentials of plant-based substance to inhabit and probable cure for the COVID-19. Turk. J. Biol 2020, 44, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ul Qamar, M.T.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Alamri, M.A.; Chen, L.L. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and anti-COVID-19 drug discovery from medicinal plants. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020, 10, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y. Traditional Chinese medicine treatment of COVID-19. Complement. Clin. Pr. 2020, 39, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devanssh, M. Possible plant based medicines and phytochemicals to be cure for deadly coronavirus COVID 19. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 9, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, J.S.; Johnson, J.B.; Steel, J.C.; Broszczak, D.A.; Neilsen, P.M.; Walsh, K.B.; Naiker, M. Natural product-derived phytochemicals as potential agents against coronaviruses: A review. Virus Res. 2020, 284, 197989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.; Joshi, T.; Sharma, P.; Mathpal, S.; Pundir, H.; Bhatt, V.; Chandra, S. In silico screening of natural compounds against COVID-19 by targeting Mpro and ACE2 using molecular docking. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 24, 4529–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.R.; Cao, Q.D.; Hong, Z.S.; Tan, Y.Y.; Chen, S.D.; Jin, H.J.; Tan, K.S.; Wang, D.Y.; Yan, Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak–an update on the status. Mil. Med Res. 2020, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjhu, R.K.; Mudgal, P.P.; Maity, H.; Dowarha, D.; Devadiga, S.; Nag, S.; Arunkumar, G. Herbal plants and plant preparations as remedial approach for viral diseases. Virusdisease 2015, 26, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Latheef, S.K.; Ahmed, I.; Iqbal, H.; Bule, M.H.; Dhama, K.; Samad, H.A.; Karthik, K.; Alagawany, M.; El-Hack, M.E.; et al. Herbal immunomodulators—A remedial panacea for designing and developing effective drugs and medicines: Current scenario and future prospects. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 264–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhama, K.; Karthik, K.; Khandia, R.; Munjal, A.; Tiwari, R.; Rana, R.; Khurana, S.K.; Ullah, S.; Khan, R.U.; Alagawany, M.; et al. Medicinal and therapeutic potential of herbs and plant metabolites / extracts countering viral pathogens—Current knowledge and future prospects. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavizadeh, L.; Ghasemi, S. Genotype and phenotype of COVID-19: Their roles in pathogenesis. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, S1684-1182(20)30082-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Haan, C.A.; Kuo, L.; Masters, P.S.; Vennema, H.; Rottier, P.J. Coronavirus particle assembly: Primary structure requirements of the membrane protein. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 6838–6850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Boheemen, S.; de Graaf, M.; Lauber, C.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Raj, V.S.; Zaki, A.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Haagmans, B.L.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Snijder, E.J.; et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. mBio 2012, 3, e00473-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czub, M.; Weingartl, H.; Czub, S.; He, R.; Cao, J. Evaluation of modified vaccinia virus Ankara based recombinant SARS vaccine in ferrets. Vaccine 2005, 23, 2273–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South, A.M.; Brady, T.M.; Flynn, J.T. ACE2 (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2), COVID-19, and ACE Inhibitor and Ang II (Angiotensin II) receptor blocker use during the pandemic: The pediatric perspective. Hypertension 2020, 76, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sola, I.; Almazan, F.; Zuniga, S.; Enjuanes, L. Continuous and discontinuous RNA synthesis in coronaviruses. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2015, 2, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebuhr, J. Coronavirus replication and reverse genetics. In Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Enjuanes, L., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 287, pp. 57–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebera, J.; Dubankova, A.; Sychrovský, V.; Ruzek, D.; Boura, E.; Nencka, R. The structural model of Zika virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in complex with RNA for rational design of novel nucleotide inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.E. Rhabdovirus. In Medical Microbiology, 4th ed.; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, R.J.; Zhang, W.; Rossmann, M.G.; Pletnev, S.V.; Corver, J.; Lenches, E.; Jones, C.T.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Chipman, P.R.; Strauss, E.G.; et al. Structure of dengue virus: Implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Cell 2002, 108, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilani, T.N.; Jamil, R.T.; Siddiqui, A.H. H1N1 influenza (swine flu). In StatPearls; Stat Pearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan, V.K.; Duan, B.; Reid, S.P. Chikungunya virus: Pathophysiology, mechanism, and modeling. Viruses 2017, 9, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Saphire, E.O. Ebolavirus glycoprotein structure and mechanism of entry. Future Virol. 2009, 4, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bafna, K.; Krug, R.M.; Montelione, G.T. Structural similarity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and HCV NS3/4A proteases suggests new approaches for identifying existing drugs useful as COVID-19 therapeutics. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Bhattacharjee, U.; Chakrabarti, A.K.; Tewari, D.N.; Banu, H.; Dutta, S. Emergence of novel coronavirus and COVID-19: Whether to stay or die out? Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 46, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanales-Belasio, E.; Raimondo, M.; Suligoi, B.; Buttò, S. HIV virology and pathogenetic mechanisms of infection: A brief overview. Ann. Sanita 2010, 46, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.M.; Gupta, S.; Bhargava, S. Potential use of Turmeric in COVID-19. Clin. Exp. Derm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, L.; Li, J.; Zhong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Clarke, M.; Jin, R. Traditional Chinese herbal medicine for treating novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junhai, J. Inventor Herbal Medicine for Treating and Preventing Rabies, Herbal Medicine for Treating and Preventing Rabies. Patent No. CN 200510032451, 23 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bliah, M.A.M. Google Patents. Antiviral Composition. Patent No. EP19850109500, 19 August 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chandan, B.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Anand, K.K. Boerhaavia diffusa: A study of its hepatoprotective activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991, 31, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.N.; Awasthi, L.P. Occurrence of a highly antiviral agent in plants treated with Boerhaavia diffusa inhibitor. Can. J. Bot. 1980, 58, 2141–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, S.; Kataria, S.K.; Sastry, K.V.; Rana, S.V. Phytochemical screening of methanolic extract and antibacterial activity of active principles of hepatoprotective herb, Eclipta alba. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2010, 2010, 3. Available online: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ebl/vol2010/iss3/3 (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Anbazhagan, G.K.; Palaniyandi, S.; Joseph, B. Antiviral Plant Extracts. In Plant Extracts; Intech Open Dekebo, A: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razdan, R.; Dev, M.A. Preventive and curative effects of Vedic Guard against antitubercular drugs induced hepatic damage in rats. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2008, 4, 182–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, P.K. Antiviral evaluation of herbal drugs. Qual. Control. Eval. Herb. Drugs 2019, 599–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.R.; Du, K.; Weemhoff, J.L.; Jaeschke, H. Critical review of resveratrol in xenobiotic-induced hepatotoxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 86, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortegiani, A.; Ingoglia, G.; Ippolito, M.; Giarratano, A.; Einav, S. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J. Crit. Care 2020, 57, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Agostinis, P.; Rabson, A.; Melino, G.; Carafoli, E.; Shi, Y.; Sun, E. Is hydroxychloroquine beneficial for COVID-19 patients? Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, A.; Shaikh, A.; Singh, R.; Misra, A. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 with or without diabetes: A systematic search and a narrative review with a special reference to India and other developing countries. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Shivaprasad Shetty, M.; V Anil Kumar, N.; Živković, J.; Calina, D.; Oana Docea, A.; Emamzadeh-Yazdi, S.; Sibel Kılıç, C.; Goloshvili, T.; Nicola, S.; et al. Veronica plants-drifting from farm to traditional healing, food application, and phytopharmacology. Molecules 2019, 24, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, K.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.; Ullah, R.; Mahmood, H.M.; Parveen, B.; Rashid, N.; Sultana, S.; Shah, S.N. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat skin diseases in northern Pakistan. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, D.; Ojha, D.; Mondal, S.; Goswami, D. Validation of antiviral potential of herbal ethnomedicine. In Evidence-Based Validation of Herbal Medicine; Mukherjee, P.K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Rawat, D.S. Medicinal plants of the family Caryophyllaceae: A review of ethno-medicinal uses and pharmacological properties. Integr. Med. Res. 2015, 4, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umesh, K.D.; Selvaraj, C.; Singh, S.K.; Dubey, V.K. Identification of new anti-nCoV drug chemical compounds from Indian spices exploiting SARS-CoV-2 main protease as target. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, P.; Shekhar, N.; Prajapat, M. In-silico homology assisted identification of inhibitor of RNA binding against 2019-nCoV N-protein (N terminal domain). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.K.; Vemula, S.; Donde, R.; Gouda, G.; Behera, L.; Vadde, R. In-silico approaches to detect inhibitors of the human severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein ion channel. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.K.; Prasad, S.K.; Islam, M.A.; Gurav, S.S.; Patil, R.B.; AlFaris, N.A.; Aldayel, T.S.; AlKehayez, N.M.; Wabaidur, S.M.; Shakya, A. Identification of bioactive compounds from Glycyrrhiza glabra as possible inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and non-structural protein-15: A pharmacoinformatics study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore, C.; Eisenhut, M.; Krausse, R.; Ragazzi, E.; Pellati, D.; Armanini, D.; Bielenberg, J. Antiviral effects of Glycyrrhiza species. Phytother. Res. Int. J. Devoted Pharmacol. Toxicol. Eval. Nat. Prod. Deriv. 2008, 22, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, M.; Geiler, J.; Naczk, P.; Sithisarn, P.; Leutz, A.; Doerr, H.W.; Cinatl, J., Jr. Glycyrrhizin exerts antioxidative effects in H5N1 influenza A virus-infected cells and inhibits virus replication and pro-inflammatory gene expression. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murck, H. Symptomatic Protective action of glycyrrhizin (licorice) in COVID-19 Infection? Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LuoLiu, P.; Li, J. Pharmacologic perspective: Glycyrrhizin may be an efficacious therapeutic agent for COVID-19. Int J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 105995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C.; Vergoten, G. Glycyrrhizin: An alternative drug for the treatment of COVID-19 infection and the associated respiratory syndrome? Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 214, 107618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S. Some FDA Approved drugs exhibit binding affinity as high as-16.0 kcal/mol against COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro): A molecular docking study. IndiaRxiv 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.; Sharma, S.; Acharya, J.; Parida, M. Assessment of In vitro antiviral activity of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) against pandemic swine flu H1N1 virus infection. World Res. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 3, 062–067. [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra, P.K.; Chopdar, K.S.; Dash, G.C.; Raval, M.K. In silico screening of phytochemicals of Ocimum sanctum against main protease of SARS-CoV-2. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purthvish, R.; Gopinatha, S.M. Antiviral prospective of Tinospora cordifolia on HSV-1. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci 2018, 7, 3617–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krupanidhi, S.; Abraham, P.K.; Venkateswarulu, T.C.; Ayyagari, V.S.; Nazneen Bobby, M.; John Babu, D.; Venkata Narayana, A.; Aishwarya, G. Screening of phytochemical compounds of Tinospora cordifolia for their inhibitory activity on SARS-CoV-2: An in silico study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donma, M.M.; Donma, O. The effects of Allium sativum on immunity within the scope of COVID-19 infection. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 144, 109934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuy, B.T.P.; My, T.T.A.; Hai, N.T.T.; Hieu, L.T.; Hoa, T.T.; Thi Phuong Loan, H.; Triet, N.T.; Anh, T.T.V.; Quy, P.T.; Tat, P.V.; et al. Investigation into SARS-CoV-2 resistance of compounds in garlic essential oil. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 8312–8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintachai, P.; Kaur, P.; Lee, R.C.; Ramphan, S.; Kuadkitkan, A.; Wikan, N.; Ubol, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Chu, J.J.; Smith, D.R. Activity of andrographolide against chikungunya virus infection. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugan, N.A.; Pandian, C.J.; Jeyakanthan, J. Computational investigation on Andrographis paniculata phytochemicals to evaluate their potency against SARS-CoV-2 in comparison to known antiviral compounds in drug trials. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enmozhi, S.K.; Raja, K.; Sebastine, I.; Joseph, J. Andrographolide as a potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: An in silico approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, J. Therapeutic potential of Withania somnifera: A report on phyto-pharmacological properties. Int J. Pharm Sci Res 2014, 5, 2131–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Junaid, N.; Raman, B. A review on pharmacological profile of Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha). Res. Rev. J. Bot. Sci. 2013, 2, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Saiyed, A.; Jahan, N.; Majeedi, S.F.; Roqaiya, M. Medicinal properties, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Withania somnifera: An important drug of Unani medicine. J. Sci. Innov. Res. 2016, 5, 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, A.; Agrawal, V.; Shandilya, A.; Bisaria, V.S.; Sundar, D. Non-nucleosidic inhibition of Herpes simplex virus DNA polymerase: Mechanistic insights into the anti-herpetic mode of action of herbal drug withaferin A. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, M.K.; Singh, P.; Sharma, S.; Singh, T.P.; Ethayathulla, A.S.; Kaur, P. Identification of bioactive molecule from Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha) as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikhale, R.V.; Gurav, S.S.; Patil, R.B.; Sinha, S.K.; Prasad, S.K.; Shakya, A.; Shrivastava, S.K.; Gurav, N.S.; Prasad, R.S. Sars-cov-2 host entry and replication inhibitors from Indian ginseng: An in-silico approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichsyani, M.; Ridhanya, A.; Risanti, M.; Desti, H.; Ceria, R.; Putri, D.H.; Sudiro, T.M.; Dewi, B.E. Antiviral effects of Curcuma longa L. against dengue virus in vitro and in vivo. Iniop. Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 101, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, K.; Ramedani, E.; Mohammadi, K.; Tajbakhsh, S.; Deilami, I.; Rastian, Z.; Fouladvand, M.; Yousefi, F.; Farshadpour, F. Evaluation of antiviral activities of curcumin derivatives against HSV-1 in Vero cell line. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1935–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Singh, A.K.; Kushwaha, P.P.; Prajapati, K.S.; Shuaib, M.; Senapati, S.; Kumar, S. Identification of potential natural inhibitors of SARS-CoV2 main protease by molecular docking and simulation studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, R.; Chakraborty, A.; Biswas, A.; Chowdhuri, S. Evaluation of green tea polyphenols as novel corona virus (SARS CoV-2) main protease (Mpro) inhibitors—An in silico docking and molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, M.; Ali, A.; Khan, S.; Ahmed, S.; Attique, Z.; Ur Rehman, S.; Khan, A.; Ali, H.; Rizwan, M.; Munir, A.; et al. nCOV-19 peptides mass fingerprinting identification, binding, and blocking of inhibitors flavonoids and anthraquinone of Moringa oleifera and hydroxychloroquine. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Jaganath, I.; Manikam, I. Evaluation of antiviral activities of four local Malaysian Phyllanthus species against Herpes simplex viruses and possible antiviral target. Int. J. Med Sci. 2013, 10, 1817–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzohairy, A.M. Therapeutics role of Azadirachta indica (Neem) and their active constituents in diseases prevention and treatment. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2016, 7382506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.B.; Yeturu, K. Possible Anti-viral effects of Neem (Azadirachta indica) on dengue virus. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesseha, H.; Goa, E. Therapeutic value of garlic (Allium sativum): A review. Adv. Food Technol Nutr Sci Open J 2019, 5, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.S.; Pandey, S.C.; Srivastava, S.; Gupta, V.S.; Patro, B.; Ghosh, A.C. Chemistry and medicinal properties of Tinospora cordifolia (Guduchi). Indian J. Pharmacol. 2003, 35, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Paikra, B.K.; Dhongade, H.K.J.; Gidwani, B. Phytochemistry and pharmacology of Moringa oleifera Lam. J. Pharm. 2017, 20, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, P.; Pujol, C.A.; Damonte, E.B.; Ghosh, T.; Ray, B. Polysaccharides from Padina tetrastromatica: Structural features, chemical modification and antiviral activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 80, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, B.C.; Gerber, S.I.; Polonsky, T.; Belval, B.J.; Shaklee, P.N.; Holme, K. Identification of structural features of heparin required for inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 binding. Virology 1995, 206, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huheihel, M.; Ishanu, V.; Tal, J. Activity of Porphyridium sp. polysaccharide against herpes simplex viruses in vitro and in vivo. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2002, 50, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbole, O.O.; Akinleye, T.E.; Segun, P.A.; Faleye, T.C.; Adeniji, A.J. In vitro antiviral activity of twenty-seven medicinal plant extracts from Southwest Nigeria against three serotypes of echoviruses. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, A.; Donovan, S.M.; Kuhlenschmidt, M.S. Soy isoflavones and virus infections. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.L.; Liu, B.; Qin, H.L.; Lee, S.M.; Wang, Y.T.; Du, G.H. Anti-influenza virus activities of flavonoids from the medicinal plant Elsholtzia rugulosa. Planta Med. 2008, 74, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwa, W.; Kumar, R.; Thompson, D.; Lyerly, W.; Moore, R.; Reid, T.E.; Lowe, H.; Toyang, N. Potential of flavonoid-inspired phytomedicines against COVID-19. Molecules 2020, 25, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, D.; Nandi, R.; Kumar, D. Evaluation of flavonoids as 2019-nCoV cell entry inhibitor through molecular docking and pharmacological analysis. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colunga Biancatelli, R.M.L.; Berrill, M.; Catravas, J.D.; Marik, P.E. Quercetin and vitamin C: An experimental, synergistic therapy for the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 related disease (COVID-19). Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, M.; Naveed, M.; Arif, M.; Kakar, M.U.; Manzoor, R.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Alagawany, M.; Tiwari, R.; Khandia, R.; Munjal, A.; et al. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) and l-theanine: Medicinal values and beneficial applications in humans-A comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharm. 2017, 95, 1260–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.M.; Lee, K.H.; Seong, B.L. Antiviral effect of catechins in green tea on influenza virus. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, C.E.; Wen, G.Y.; Xu, W.; Jia, J.H.; Rohan, L.; Corbo, C.; Di Maggio, V.; Jenkins, E.C.; Hillier, S. Epigallocatechin gallate inactivates clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, A.B.; Kanungo, N.; Nayak, V.; Chainy, G.B.N.; Dandapat, J. Catechin and curcumin interact with corona (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV2) viral S protein and ACE2 of human cell membrane: Insights from computational study and implication for intervention. Nature 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, M.; Danielewska-Nikiel, B.; Borzelleca, J.F.; Flamm, G.W.; Williams, G.M.; Lines, T.C. A critical review of the data related to the safety of quercetin and lack of evidence of in vivo toxicity, including lack of genotoxic/carcinogenic properties. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 2179–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, O.; Fontanes, V.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Loo, R.; Loo, J.; Arumugaswami, V.; Sun, R.; Dasgupta, A.; French, S.W. The heat shock protein inhibitor Quercetin attenuates hepatitis C virus production. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmetov, L.; Gal-Tanamy, M.; Shapira, A.; Vorobeychik, M.; Giterman-Galam, T.; Sathiyamoorthy, P.; Golan-Goldhirsh, A.; Benhar, I.; Tur-Kaspa, R.; Zemel, R. Suppression of hepatitis C virus by the flavonoid quercetin is mediated by inhibition of NS3 protease activity. J. Viral Hepat. 2012, 19, e81–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Faris, A.N.; Comstock, A.T.; Wang, Q.; Nanua, S.; Hershenson, M.B.; Sajjan, U.S. Quercetin inhibits rhinovirus replication in vitro and in vivo. Antivir. Res. 2012, 94, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, K.; Teoh, B.T.; Sam, S.S.; Wong, P.F.; Mustafa, M.R.; Abu Bakar, S. Antiviral activity of four types of bioflavonoid against dengue virus type-2. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakobyan, A.; Arabyan, E.; Avetisyan, A.; Abroyan, L.; Hakobyan, L.; Zakaryan, H. Apigenin inhibits African swine fever virus infection in vitro. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 3445–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Qiu, M.; Chen, D.; Zheng, N.; Jin, Y.; Wu, Z. Apigenin inhibits enterovirus 71 replication through suppressing viral IRES activity and modulating cellular JNK pathway. Antivir. Res. 2014, 109, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogerio, A.P.; Dora, C.L.; Andrade, E.L.; Chaves, J.S.; Silva, L.F.; Lemos-Senna, E.; Calixto, J.B. Anti-inflammatory effect of quercetin-loaded microemulsion in the airways allergic inflammatory model in mice. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 1, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qiao, H.; Lv, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Hou, Y.; Tan, R.; Li, E. Apigenin inhibits enterovirus-71 infection by disrupting viral RNA association with trans-acting factors. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, C.; Ohno, M.; Otsuka, M.; Kishikawa, T.; Goto, K.; Muroyama, R.; Kato, N.; Yoshikawa, T.; Takata, A.; Koike, K. The flavonoid apigenin inhibits hepatitis C virus replication by decreasing mature microRNA122 levels. Virology 2014, 462, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, X. Baicalin benefits the anti-HBV therapy via inhibiting HBV viral RNAs. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2017, 323, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithisarn, P.; Michaelis, M.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M.; Cinatl Jr, J. Differential antiviral and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of the flavonoids biochanin A and baicalein in H5N1 influenza A virus-infected cells. Antivir. Res. 2013, 97, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Dou, J.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, C. Inhibitory effects of baicalein on the influenza virus in vivo is determined by baicalin in the serum. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 33, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Chen, L.; Xu, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Su, Z.; Ke, M.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, C. Effects of baicalein on Sendai virus in vivo are linked to serum baicalin and its inhibition of hemagglutinin-neuraminidase. Arch. Virol. 2011, 156, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, M.B.; Chu, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.D. Role of Baicalin in anti-influenza virusA as a potent inducer of IFN gamma. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 263630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Qian, S.; Qian, P.; Li, X. Antiviral activity of luteolin against Japanese encephalitis virus. Virus Res. 2016, 220, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipping, K.; Garssen, J.; van’t, L.B. An evaluation of the inhibitory effects against rotavirus infection of edible plant extracts. Virol. J. 2012, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali, K.S.; Sivasubramanian, S.; Vincent, S.; Murugan, S.B.; Giridaran, B.; Dinesh, S.; Gunasekaran, P.; Krishnasamy, K.; Sathishkumar, R. Anti-chikungunya activity of luteolin and apigenin rich fraction from Cynodon dactylon. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2015, 8, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Li, Z.; Yuan, K.; Qu, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H.; Luo, H.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, P.; et al. Small molecules blocking the entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into host cells. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 11334–11339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehla, R.; Bivalkar-Mehla, S.; Chauhan, A. Aflavonoid, luteolin, cripples HIV-1 by abrogation of tat function. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Myszka, D.G.; Tendian, S.W.; Brouillette, C.G.; Sweet, R.W.; Chaiken, I.M.; Hendrickson, W.A. Kinetic and structural analysis of mutant CD4 receptors that are defective in HIV gp120 binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 15030–15035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Su, W.; Jin, J.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.; Sun, S.; Fan, P.; An, D.; et al. Identification of luteolin as enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 inhibitors through reporter viruses and cell viability-based screening. Viruses 2014, 6, 2778–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, W.A.; Ahamad, T.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, Z.A.; Khan, M.F. Luteolin: A dietary molecule as potential anti-COVID-19 agent. Comput. Chem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrocotsa, D.; Mitaku, S.; Axarlis, S.; Harvala, C.; Malamas, M. Evaluation of the antiviral activity of kaempferol and its glycosides against human cytomegalovirus. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Sauter, D.; Wang, K.; Zhang, R.; Sun, B.; Karioti, A.; Bilia, A.R.; Efferth, T.; Schwarz, W. Kaempferol derivatives as antiviral drugs against the 3a channel protein of coronavirus. Planta Med. 2014, 80, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lin, J.; Zhou, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, B. Activity of compounds from Taxillus sutchuenensis as inhibitors of HCV NS3serine protease. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 13, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.J.; Ryu, Y.B.; Park, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kwon, H.-J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, K.H.; Rho, M.-C.; Lee, W.S. Neuraminidase inhibitory activities of flavonols isolated from Rhodiola rosea roots and their in vitro anti-influenza viral activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 6816–6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, Z.; Du, J.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, F.; Jin, Q. Anti-Japanese-encephalitis-viral effects of kaempferol and daidzin and their RNA-binding characteristics. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owis, A.I.; El-Hawary, M.S.; Dalia, E.L.; Amir Omar, M.A.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Kamel, M.S. Molecular docking reveals the potential of Salvadora persica flavonoids to inhibit COVID-19 virus main protease. RSC Adv. 1957, 10, 19570–19575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieven, M.; Vlietinick, A.J.; Berghe, D.V.; Totte, J.; Dommisse, R.; Esmans, E.; Alderweireldt, F. Plant antiviral agents. III. Isolation of alkaloids from Clivia miniata Regel (Amaryl-lidaceae). J. Nat. Prod. 1982, 45, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H.Q.; Guo, H.Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Hua, S.N.; Yu, J.; Xiao, P.G.; et al. Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2005, 67, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamand, L.; Lautenschlager, I.; Krueger, G.; Ablashi, D. (Eds.) Human Herpesviruses HHV-6A, HHV-6B and HHV-7: Diagnosis and Clinical Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, G.; Ding, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Jin, Z.; Yang, G.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Li, W. Antiviral activity of sophoridine against enterovirus 71 in vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 236, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Ye, G.; Huang, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, R.; Yu, Y.; Cui, X. Antiviral effects of sophoridine against coxsackievirus B3 and its pharmacokinetics in rats. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleasel, M.D.; Peterson, G.M. Emetine, Ipecac, Ipecac, Alkaloids and analogues as potential antiviral agents for coronaviruses. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoros, M.; Fauconnier, B.; Girre, R.L. In vitro antiviral activity of a saponin from Anagallis arvensis, Primulaceae, against herpes simplex virus and poliovirus. Antivir. Res. 1987, 8, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, C.M.; Amoros, M.; Girre, L. Mechanism of antiviral activity of triterpenoid saponins. Phytother. Res. 1999, 13, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Ren, J.; Ma, X.; Liu, L.; Yu, S.; Li, X.; Li, H. Polyphylla saponin I has antiviral activity against influenza A virus. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 18963. [Google Scholar]

- Bahbah, E.I.; Negida, A.; Nabet, M.S. Purposing saikosaponins for the treatment of COVID-19. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 140, 109782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.M.; Shen, X.; Cao, Y.K.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.X. Discovery of anti-2019-nCoV agents from Chinese patent drugs via docking screening. Hypothesis 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teponno, R.B.; Kusari, S.; Spiteller, M. Recent advances in research on lignans and neolignans. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 1044–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.L.; Huang, Y.L.; Ou, J.C.; Chen, C.C.; Hsu, F.L.; Chang, C. Screening of 25 compounds isolated from Phyllanthus species for anti-human hepatitis B virus in vitro. Phytother. Res. 2003, 17, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wei, W.; Shi, K.; Cao, X.; Zhou, M.; Liu, Z. In vitro and in vivo anti-hepatitis B virus activities of the lignan niranthin isolated from Phyllanthus niruri L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Acosta, R.; Bautista-Carbajal, P.; Syed, G.H.; Siddiqui, A.; DelAngel, R.M. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) inhibits replication and viral morphogenesis of dengue virus. Antivir. Res. 2014, 109, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, G.H.; Siddiqui, A. Effects of hypolipidemic agent nordihydroguaiaretic acid on lipid droplets and hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2011, 54, 1936–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Ramos, T.; de Oya, N.J.; Saiz, J.C.; Martín-Acebes, M.A. Antiviral activity of nordihydroguaiaretic acid and its derivative tetra-O-methyl nordihydroguaiaretic acid against West Nile virus and Zika virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00376-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Le, T.Q.; Kurihara, N.; Chida, J.; Cisse, Y.; Yano, M.; Kido, H. Influenza virus—cytokine-protease cycle in the pathogenesis of vascular hyperpermeability in severe influenza. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyegunwa, A.O.; Sikes, M.L.; Wilson, J.; Scholle, F.; Laster, S.M. Tetra-O-methyl nordihydroguaiaretic acid (Terameprocol) inhibits the NF-κB-dependent transcription of TNF-αand MCP-1/CCL2 genes by preventing RelA from binding its cognate sites on DNA. J. Inflamm. 2010, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollara, J.J.; Laster, S.M.; Petty, I.T. Inhibition of poxvirus growth by Terameprocol, a methylated derivative of nordihydroguaiaretic acid. Antivir. Res. 2010, 88, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Teng, L.; Li, J.N.; Park, R.; Mold, D.E.; Gnabre, J.; Hwu, J.R.; Tseng, W.N.; Huang, R.C. Antiviral activities of methylated nordihydroguaiaretic acids. 2. Targeting herpes simplex virus replication by the mutation insensitive transcription inhibitor tetra-O-methyl-NDGA. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 3001–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnabre, J.N.; Brady, J.N.; Clanton, D.J.; Ito, Y.; Dittmer, J.; Bates, R.B.; Huang, R.C. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription and replication by DNA sequence-selective plant lignans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 11239–11243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, N.; Dalby, R.; Tan, M.; Arnold, S.; Stern, J.; Frazer, N. Phase I/II clinical safety studies of terameprocol vaginal ointment. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 107, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Dong, X.; Kang, T.G. Activity of in vitro anti-influenza virus of arctigenin. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2002, 33, 724–725. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Xu, P.; Liu, N.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Hu, Y. Antiviral effect of arctigenin compound on influenza virus. Tradit. Chin. Drug Res. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.; Narutaki, K.; Nagaoka, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Uesato, S. Therapeutic effect of arctiin and arctigenin in immunocompetent and immunocompromised mice infected with influenza A virus. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 33, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, H.C.; Merz, H.; Steffen, R.; Müller, W.E.; Sarin, P.S.; Trumm, S.; Schulz, J.; Eich, E. Differential in vitro anti-HIV activity of natural lignans. Z. Für Nat. 1990, 45, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eich, E.; Pertz, H.; Kaloga, M.; Schulz, J.; Fesen, M.R.; Mazumder, A.; Pommier, Y. -Arctigenin as a lead structure for inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 integrase. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.C.; Kuo, Y.H.; Lin, Y.L.; Tsai, W.J. Yatein from Chamaecyparis obtusa suppresses herpes simplex virus type 1 replication in HeLa cells by interruption the immediate-early gene expression. Antivir. Res. 2006, 70, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Kaushik, A.C.; Muhammad, J.; Khan, A.; Dai, H.; Wei, D.Q. New strategy for identifying potential natural HIV-1 non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors against drug-resistance: An in silico study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, P.; Zhang, T.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Shen, W. Effects of diphyllin as a novel V-ATPase inhibitor on TE-1 and ECA-109 cells. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesmelova, E.F.; Razakova, D.M.; Akhmedzhanova, V.I.; Bessonova, I.A. Diphyllin from Haplophyllum alberti-regelii, H. bucharicum, and H. perforatum. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1983, 19, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.G.; Henriksen, K.; Neutzsky-Wulff, A.V.; Dziegiel, M.; Karsdal, M.A. Diphyllin, a novel and naturally potent V-ATPase inhibitor, abrogates acidification of the osteoclastic resorption lacunae and bone resorption. J. Bone Min. Res. 2007, 22, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Lopez, A.; Persaud, M.; Chavez, M.P.; Zhang, H.; Rong, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, T.T.; Sarafianos, S.G.; Diaz-Griffero, F. Glycosylated diphyllin as a broad-spectrum antiviral agent against Zika virus. EBioMedicine 2019, 47, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.W.; Cheng, J.X.; Liu, M.T.; King, K.; Peng, J.Y.; Zhang, X.Q.; Wang, C.H.; Shresta, S.; Schooley, R.T.; Liu, Y.T. Inhibitory and combinatorial effect of diphyllin, a v-ATPase blocker, on influenza viruses. Antivir. Res. 2013, 99, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susplugas, S.; Hung, N.V.; Bignon, J.; Thoison, O.; Kruczynski, A.; Sévenet, T.; Guéritte, F. Cytotoxic arylnaphthalene lignans from a Vietnamese acanthaceae, Justicia p atentiflora. J. Nat. Prod 2005, 68, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Rumschlag-Booms, E.; Guan, Y.F.; Liu, K.L.; Wang, D.Y.; Li, W.F.; Cuong, N.M.; Soejarto, D.D.; Fong, H.H.; Rong, L. Anti-HIV diphyllin glycosides from Justicia gendarussa. Phytochemistry 2017, 136, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, J.I.; Lin, Q.; Li, C.; Zhu, Q.; Zhong, N. Antiviral activity of Isatis indigotica root-derived clemastanin B against human and avian influenza A and B viruses in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 31, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.T. Bicyclol: A novel drug for treating chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Med. Chem. 2009, 5, 29–43. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ben/mc/2009/00000005/00000001/art00005. (accessed on 12 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.T. New drugs derived from medicinal plants. Therapie 2002, 57, 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, B.; Wang, J.W.; Bai, X.L. Comparison of bicyclol therapy for patients with genotype B and C of hepatitis B virus. Zhonghua shi yan he lin chuang bing du xue za zhi= Zhonghua shiyan he linchuang bingduxue zazhi = Chin. J. Exp. Clin. Virol. 2007, 21, 366–368. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.H.; Jassey, A.; Hsu, H.Y.; Lin, L.T. Antiviral activities of silymarin and derivatives. Molecules 2019, 24, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Choi, H.J. Silymarin efficacy against influenza A virus replication. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 832–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Du, R.; Liu, M.; Rong, L. Lignans and their derivatives from plants as antivirals. Molecules 2020, 25, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.C.; Kuo, Y.H.; Jan, J.T.; Liang, P.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Liu, H.G.; Lee, C.K.; Chang, S.T.; Kuo, C.J.; Lee, S.S.; et al. Specific plant terpenoids and lignoids possess potent antiviral activities against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 4087–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Galabov, A.S.; Mileva, M. Tannins as antiviral agents. Tannins-structural properties, biological properties and current knowledge. Alfredo Aires 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.M.; Cheng, H.Y.; Lin, T.C.; Chiang, L.C.; Lin, C.C. The in vitro activity of geraniin and 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose isolated from Phyllanthus urinaria against herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 infection. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 110, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notka, F.; Meier, G.; Wagner, R. Concerted inhibitory activities of on HIV replication In vitro and ex vivo. Antivir. Res. 2004, 64, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.T.; Chen, T.Y.; Chung, C.Y.; Noyce, R.S.; Grindley, T.B.; McCormick, C.; Lin, T.C.; Wang, G.H.; Lin, C.C.; Richardson, C.D. Hydrolyzable tannins (chebulagic acid and punicalagin) target viral glycoprotein-glycosaminoglycan interactions to inhibit herpes simplex virus 1 entry and cell-to-cell spread. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 4386–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhelmova, N.; Jacquet, R.; Quideau, S.; Stoyanova, A.; Galabov, A.S. Three-dimensional analysis of combination effect of ellagitannins and acyclovir on herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Antivir. Res. 2011, 89, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Jacquet, R.; Quideau, S.; Galabov, A.S. Ellagitannins as synergists of ACV on the replication of ACV-resistant strains of HSV 1 and 2. Antivir. Res. 2014, 110, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Sirakov, I.; Jacquet, R.; Deffieux, D.; Quideau, S.; Galabov, A.S. Antiviral activities of ellagitannins against bovine herpesvirus 1, suid alphaherpesvirus 1 and caprine herpesvirus 1. J. Vet. Med. Anim. Health 2020, 12, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Deffieux, D.; Quideau, S. Castalagin: Some aspects of the mode of anti-herpes virus activity. Ann. Antivir. Antiretrovir. 2018, 2, 004–007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, T.S.; Azmi, D.Z.; Permanasari, A.; Adianti, M.; Lydia, T.; Widiandani, T.; Aoki, U.C.; Widyawaruyanti, A.; Fuad, A.; Hak, H. Anti-viral activity of Phyllanthus niruri against hepatitis c virus. Malays. Appl. Biol. 2019, 48, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dhama, K.; Karthik, K.; Khandia, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Munjal, A.; Latheef, S.K.; Kumar, D.; Ramakrishnan, M.A.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.; et al. Advances in designing and developing vaccines, drugs, and therapies to counter Ebola virus. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munjal, A.; Khandia, R.; Dhama, K.; Sachan, S.; Karthik, K.; Tiwari, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Kumar, D.; Singh, R.K.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; et al. Advances in developing therapies to combat Zika virus: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.K.; Dhama, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Tiwari, R.; Natesan, S.; Khandia, R.; Munjal, A.; Vora, K.S.; Latheef, S.K.; Karthik, K.; et al. Nipah virus: Epidemiology, pathology, immunobiology and advances in diagnosis, vaccine designing and control strategies—A comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 2019, 39, 26–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, C.; Hood, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Kan, J.; Du, J. A novel combination of vitamin C, curcumin and glycyrrhizic acid potentially regulates immune and inflammatory response associated with coronavirus infections: A perspective from system biology analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhama, K.; Sharun, K.; Tiwari, R.; Dadar, M.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, K.P.; Chaicumpa, W. COVID-19, an emerging coronavirus infection: Advances and prospects in designing and developing vaccines, immunotherapeutics, and therapeutics. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2020, 16, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangal, N.; Nagle, V.; Pawar, Y.; Dasgupta, S. Reconsidering traditional medicinal plants to combat COVID-19. AIJR 2020. Available online: https://preprints.aijr.org/index.php/ap/preprint/view/34 (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Malik, Y.S.; Kumar, N.; Sircar, S.; Kaushik, R.; Bhat, S.; Dhama, K.; Gupta, P.; Goyal, K.; Singh, M.P.; Ghoshal, U.; et al. Coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19): Challenges and a global perspective. Pathogens 2020, 9, E519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, S.; Pandey, D.N.; Singh, R.H. COVID-19 Pandemic: A pragmatic plan for Ayurveda intervention. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellingiri, B.; Jayaramayya, K.; Iyer, M.; Narayanasamy, A.; Govindasamy, V.; Giridharan, B.; Ganesan, S.; Venugopal, A.; Venkatesan, D.; Ganesan, H.; et al. COVID-19: A promising cure for the global panic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Islam, M.S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, X. Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of patients infected with 2019-new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A review and perspective. Int J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatoo, M.I.; Hamid, Z.; Parray, O.R.; Wani, A.H.; Ul Haq, A.; Saxena, A.; Patel, S.K.; Pathak, M.; Tiwari, R.; Malik, Y.S.; et al. COVID-19—Recent advancements in identifying novel vaccine candidates and current status of upcoming SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhama, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Tiwari, R.; Verma, A.K.; Saminathan, M.; Amarpal, Y.M.; Nikousefat, Z.; Javdani, M.; Khan, R.U. A concept paper on novel technologies boosting production and safeguarding health of humans and animals. Res. Opin. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2014, 4, 353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Alagawany, M.; Farag, M.R.; Arif, M.; Emam, M.; Dhama, K.; Sarwar, M.; Sayab, M. Nutritional and pharmaceutical applications of nanotechnology: Trends and advances. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 13, 340–350. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, M.; Lambe, U.P.; Brar, B.; Shah, I.; Manimegalai, J.; Ranjan, K.; Rao, R.; Kumar, S.; Mahant, S.; Khurana, S.K.; et al. Nanotherapeutics: An insight into healthcare and multi-dimensional applications in medical sector of the modern world. Biomed. Pharm. 2018, 97, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkotoky, S.; Banerjee, M. A computational prediction of SARS-CoV-2 structural protein inhibitors from Azadirachta indica (Neem). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoharan, Y.; Haridas, V.; Vasanthakumar, K.C.; Muthu, S.; Thavoorullah, F.F.; Shetty, P. Curcumin: A wonder drug as a preventive measure for COVID19 management. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2020, 35, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedipour, F.; Hosseini, S.A.; Sathyapalan, T.; Majeed, M.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Banach, M.; Sahebkar, A. Potential effects of curcumin in the treatment of COVID-19 infection. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2911–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughn, A.R.; Kakar, S.S. Withaferin A: A potential therapeutic agent against COVID-19 infection. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Khan, F.; Kumar, A.; Srivastava, A. Screening of potent inhibitors against 2019 novel coronavirus (Covid-19) from Allium sativum and Allium cepa: An in silico approach. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2020, 11, 7981–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, D.; Gomes, J.; Lopes, L.; Hinzmann, M.; Machado, J. A review of properties, nutritional and pharmaceutical applications of Moringa oleifera: Integrative approach on conventional and traditional Asian medicine. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2020, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Moccia, S.; Spagnuolo, C.; Tedesco, I.; Russo, G.L. Roles of flavonoids against coronavirus infection. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 109211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Yao, S.; Zhao, W.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Shang, W.; Xie, H.; Ke, C.; Gao, M.; Yu, K.; et al. Discovery of baicalin and baicalein as novel, natural product inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease in vitro. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, R.; Arnason, J.T.; Trudeau, V.; Bergeron, C.; Budzinski, J.W.; Foster, B.C.; Merali, Z. Phytochemical and biological analysis of skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora L.): A medicinal plant with anxiolytic properties. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basha, S.H. Corona virus drugs–a brief overview of past, present and future. J. Peer Sci. 2020, 2, e1000013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Kumar, N.V.; Şener, B.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kılıç, M.; Mahady, G.B.; Vlaisavljevic, S.; Iriti, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Setzer, W.N.; et al. Medicinal plants used in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Barrera, J.; Martin-Castillo, B.; Buxó, M.; Brunet, J.; Encinar, J.A.; Menendez, J.A. Silibinin and SARS-CoV-2: Dual targeting of host cytokine storm and virus replication machinery for clinical management of COVID-19 patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, I.E.; Deniz, F.S. Natural products as potential leads against coronaviruses: Could they be encouraging structural models against SARS-CoV-2? Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2020, 10, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskar, M.A.; Choudhury, M.D. Search for therapeutics against COVID 19 targeting SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease: An in silico study. ChemRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhao, H. Arctigenin, a lignan from Arctium lappa L., inhibits metastasis of human breast cancer cells through the downregulation of MMP-2/-9 and heparanase in MDA-MB-231 cells. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Niu, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Wang, W.; Zhu, N.; Deng, Y.; Wang, H.; Ye, F.; Cen, S.; et al. High-throughput screening and identification of potent broad-spectrum inhibitors of coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.N.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Li, X.D.; Xiong, J.; Xiao, S.Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.R.; Deng, C.L.; Yang, X.L.; Wei, H.P.; et al. Gemcitabine, lycorine and oxysophoridine inhibit novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in cell culture. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1170–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, A.B.; Ali, M.A.; Lee, J.; Farah, M.A.; Al-Anazi, K.M. Unravelling lead antiviral phytochemicals for the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme through in silico approach. Life Sci. 2020, 255, 117831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Yasunaga, J.I.; Ohshima, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Matsuoka, M. Pentosan polysulfate demonstrates anti-human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 activities in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00413-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Common Name | Botanical and Family Name | Native | Parts Used | Traditional Uses | Antiviral Property |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquorice or Yashtimadu | G. glabra (Fabaceae) | Central and Southern Asia, Russia, Northern India (Sub-Himalayan and Punjab), Mediterranean, Afghanistan, and Iran | Roots | Extensively used in Indian traditional medicine systems like Ayurveda and Siddha for ulcer, aliment, purgative, demulcent, antitussive, and expectorant | SARS-related coronavirus, H5N1 influenza A virus, HCV, HIV-1. influenza A virus pneumonia, respiratory syncytial virus and SARS- CoV-2 [53,55] |

| Neem | A. indica (Meliaceae) | India, Bangladesh, Burma, Nepal, and West Africa | Leaves, roots, twigs and seeds | Different parts of neem are used as an important ingredient in Ayurveda, Unani and Homeopathy medicine | Dengue virus and SARS-CoV-2 [80,81] |

| Green chireta | A. paniculata (Acanthaceae) | South India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, USA, Thailand, Jamaica, and West Indies | Leaves and roots | The plant has a pivotal role in Chinese and Indian (Siddha and Ayurveda) traditional system for different formulation against various diseases diabetes, sore throat, fever, cirrhosis, malaria, viral hepatitis, liver cancer, and upper respiratory infections | Chikungunya virus, Influenza A, Flaviviruses, HIV antigen-positive H9 cells, and SARS-CoV-2 [65,66] |

| Tulsi | O. Sanctum (Lamiaceae) | India, Iran, Italy, Egypt, the USA, and France | Whole plant seeds, leaves and roots | The plant has been well documented in Ayurveda, Siddha, and Greek medicinal system which is used for various treatment purposes such as fever, common cold, malaria fever, epilepsy, bronchitis, migraine, headache, convulsions, hepatic disease, stomach disorders, and heart diseases | H1N1 and SARS-CoV-2 [59,60] |

| Turmeric | C. longa (Zingiberaceae) | India, Nepal, China, Bangladesh, and Pakistan | Rhizomes | In Ayurveda, turmeric has a long history of use because of the presence of various beneficial properties used in the treatment of diabetic wounds, fungal infection, cough, rheumatism, hepatic and biliary disorder | Dengue virus, HSV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 [31,74] |

| Ashwagandha | W. somnifera (Solanaceae) | India, Sind, Baluchistan, Afghanistan, and Sri Lanka | Roots | The plant is well formulated in Ayurveda, Siddha, Unani and Tibetan Medicine system. Traditionally, W. somnifera has been used to treat tumor, stress, immunomodulatory, depression, inflammatory, adaptogenic, and nervous disorder. It is also used in patients with behavioural disturbances for mood stabilization | HSV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 [68,69,70,71] |

| Garlic | A. sativum (Alliaceae) | Central Asia, China, Mediterranean region, Mexico, Egypt and in Southern and Central Europe | Cloves, flowers and leaves | Garlic has been traditionally used as hypolipidemic, antihypertensive and anti-thrombotic agent in Ayurvedic, Chinese, and Islamic medicine | Influenza virus A and SARS-CoV-2 [63,64,82] |

| Guduchi | T. cordifolia (Menispermaceae) | Indian subcontinent and China | Roots, stem and leaves | The plant is a common shrub used as anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, antiperiodic, anti-diabetic,, and anti-spasmodic properties in Ayurvedic medicine | HSV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 [62,83] |

| Drumstick | M. oleifera (Moringaceae) | Sub-Himalayan tracts of India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan | Roots, flowers, leaves and pod | The traditional use of plant includes antispasmodic, antiparalytic, antiviral, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antiepileptic, stimulant and cardiac circulatory tonic | HSV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 [78,84] |

| S. No | Name of the Compound | Structure | Antiviral Property against | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

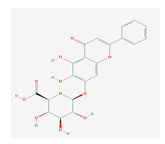

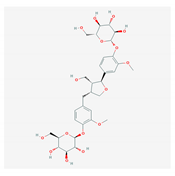

| 1. | 1. FLAVONOIDS |  | HSV-1 and HSV-2, SARS-CoV-2 | [95,97,201] |

| 1.1. Catechins (Green tea) EGCG and ECG | ||||

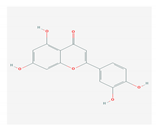

| 1.2. Quercetin (C. longa) |  | HCV and SARS-CoV-2 | [93,99,100] | |

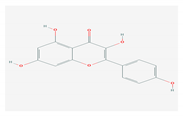

| 1.3. Apigenin (Green tea) |  | Enterovirus-71, foot and mouth disease virus, HCV, African swine fever virus, and influenza A | [103,104,105] | |

| 1.4. Baicalin (Scutellaria lateriflora) |  | Enterovirus, dengue virus, respiratory syncytical virus, Newcastle disease virus, HIV, and HBV | [108,110,112,120,202,203] | |

| 1.5. Luteolin (O. sanctum) |  | SARS-CoV-2, rhesus rota virus, chickenkuniya virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus | [113,114,115,116,120,204] | |

| 1.6. Kaempferol (F. benjamina) |  | HSV-1, HSV-2, HIV, HCV, H1NI, H9N2, Japanese encephalitis virus, and SARS-CoV-2 | [121,123,124,126] | |

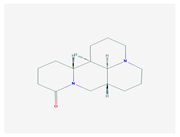

| 2. | 2. ALKALOIDS |  | Poliomyelitis virus, SARS-CoV (BJ001 and BJ006) | [127,128,132,205] |

| 2.1. Lycorine (L. radiata) | ||||

| 2.2. Sophoridine (S. flavescens) |  | Enterovirus-71 and coxsackievirus | [130,131,206] | |

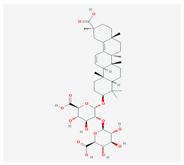

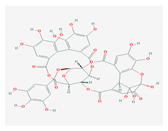

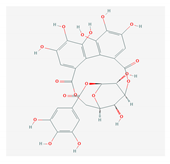

| 3. | 3. SAPONINS (A. arvensis) |  | HSV-1, poliovirus, and SARS-CoV 2 | [4,134,135,136,207] |

| 4. | 4. LIGNANS |  | HBV and duck HBV | [139,140,170,171] |

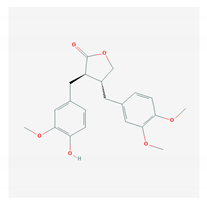

| 4.1. Nordihydroguairetic acid (P. niruri. L) |  | DENV, zika virus or West Nile virus, and influenza A virus | [140,141,142,143,144,208] | |

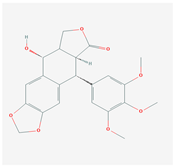

| 4.2 Arctigenin (Arctium lappa) |  | Influenza A virus and HIV-1 | [150,151,152,153,154,209] | |

| 4.3. Yatein (Chamaecyparis obtuse) |  | HSV-1 | [155,156] | |

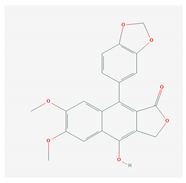

| 4.4. Diphyllin (Genus-Haplophyllum) |  | Zika virus and influenza A virus | [157,158,159,160,161,210] | |

| 4.5.Patentiflorin A (J. gendarussa) |  | Zika virus and HIV | [160,161,162,163,164,211] | |

| 4.6. Clemastanin B (Isatis indigotica) |  | Influenza A virus | [164,165,166,167] | |

| 4.7. Silymarin C (S. marianum) |  | HCV | [168,169,212] | |

| 5. | 5. TANNINS |  | HSV and HIV | [172,173,174,175] |

| 5.1. Geraniin (P. amarus) | ||||

| 5.2. 1,3,4,6-tetra-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose (P. urinaria) |  | |||

| 5.3. Corilagin (P. amarus) |  |

| S. No | Name of the Compound | Mechanism of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Polysulphates (sulphated polysaccharides) |

| [85,86,87,213] |

| 2. | EGCG and ECG |

| [95,97,201] |

| 3. | Quercetin |

| [93,99,100,101] |

| 4. | Apigenin |

| [103,104,105,106,202] |

| 5. | Baicalin |

| [108,109,110,112,120] |

| 6. | Luteolin |

| [113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,210] |

| 7. | Rhamnose residue containing kaempferol |

| [122,124,125,126] |

| 8. | Kaempferol 3,7-bisrhamnoside |

| [123] |

| 9. | Triterpene saponin |

| [131] |

| 10. | Triterpenoid saponin TS21 |

| [134,135,136] |

| 11. | Niranthin |

| [139,140] |

| 12. | Nordihydroguairetic acid |

| [141,142,143,144] |

| 13. | Terameprocol |

| [145,146,147,148,149] |

| 14. | Arctigenin |

| [150,151,152,153,154] |

| 15. | Yatein |

| [155,156] |

| 16. | Diphyllin |

| [157,158,159,160,161] |

| 17. | Patentiflorin A |

| [160,161,162,163,164] |

| 18. | Clemastanin B |

| [164,165,166,167] |

| 19. | Silymarin C |

| [168,169,170,171] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anand, A.V.; Balamuralikrishnan, B.; Kaviya, M.; Bharathi, K.; Parithathvi, A.; Arun, M.; Senthilkumar, N.; Velayuthaprabhu, S.; Saradhadevi, M.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; et al. Medicinal Plants, Phytochemicals, and Herbs to Combat Viral Pathogens Including SARS-CoV-2. Molecules 2021, 26, 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26061775

Anand AV, Balamuralikrishnan B, Kaviya M, Bharathi K, Parithathvi A, Arun M, Senthilkumar N, Velayuthaprabhu S, Saradhadevi M, Al-Dhabi NA, et al. Medicinal Plants, Phytochemicals, and Herbs to Combat Viral Pathogens Including SARS-CoV-2. Molecules. 2021; 26(6):1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26061775

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnand, Arumugam Vijaya, Balasubramanian Balamuralikrishnan, Mohandass Kaviya, Kathirvel Bharathi, Aluru Parithathvi, Meyyazhagan Arun, Nachiappan Senthilkumar, Shanmugam Velayuthaprabhu, Muthukrishnan Saradhadevi, Naif Abdullah Al-Dhabi, and et al. 2021. "Medicinal Plants, Phytochemicals, and Herbs to Combat Viral Pathogens Including SARS-CoV-2" Molecules 26, no. 6: 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26061775

APA StyleAnand, A. V., Balamuralikrishnan, B., Kaviya, M., Bharathi, K., Parithathvi, A., Arun, M., Senthilkumar, N., Velayuthaprabhu, S., Saradhadevi, M., Al-Dhabi, N. A., Arasu, M. V., Yatoo, M. I., Tiwari, R., & Dhama, K. (2021). Medicinal Plants, Phytochemicals, and Herbs to Combat Viral Pathogens Including SARS-CoV-2. Molecules, 26(6), 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26061775