Discrimination and Health: The Mediating Effect of Acculturative Stress

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Perceived Discrimination

2.4. Health Status

2.5. Acculturative Stress Scale

2.6. Procedures

2.7. Statistical Analysis

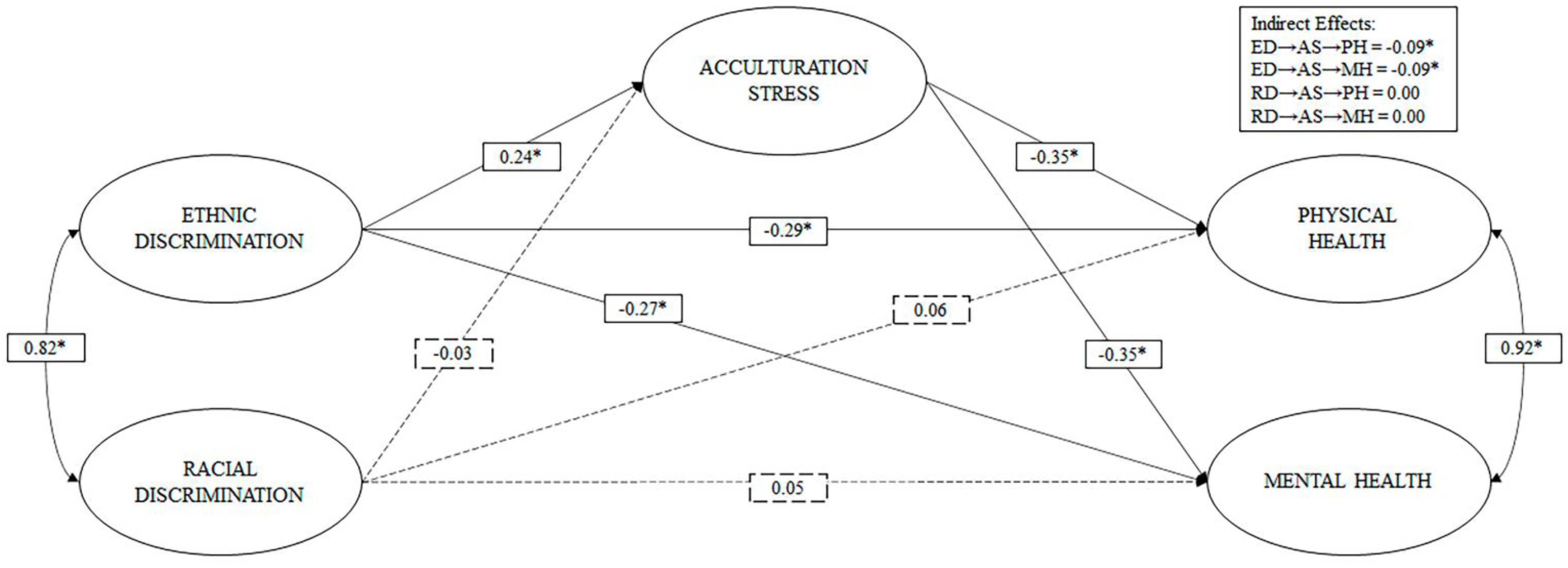

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Descriptives

3.3. Measurement Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IOM. International Organization for Migration. UN Migration. World Migration Report. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2020 (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Pascoe, E.A.; Richman, L.S. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krieger, N. A glossary for social epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2001, 55, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cormack, D.; Stanley, J.; Harris, R. Multiple forms of discrimination and relationships with health and wellbeing: Findings from national cross-sectional surveys in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Int. J. Equity Heal. 2018, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hagiwara, N.; Alderson, C.J.; Mezuk, B. Differential Effects of Personal-Level vs Group-Level Racial Discrimination on Health among Black Americans. Ethn. Dis. 2016, 26, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krieger, N. Discrimination and Health Inequities. Int. J. Heal. Serv. 2014, 44, 643–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrine, H.; Corral, I.; Hall, M.B.; Bess, J.J.; Efird, J. Self-rated health, objective health, and racial discrimination among African-Americans: Explaining inconsistent findings and testing health pessimism. J. Heal. Psychol. 2016, 21, 2514–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, A. Discrimination, Self-Esteem, and Mental Health Across Ethnic Groups of Second-Generation Immigrant Adolescents. J. Racial Ethn. Heal. Disparities 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.T.; Cogburn, C.D.; Williams, D.R. Self-Reported Experiences of Discrimination and Health: Scientific Advances, Ongoing Controversies, and Emerging Issues. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 407–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priest, N.; Perry, R.; Ferdinand, A.; Kelaher, M.; Paradies, Y. Effects over time of self-reported direct and vicarious racial discrimination on depressive symptoms and loneliness among Australian school students. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 32, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Racism and Health, I. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R. Stress and the Mental Health of Populations of Color: Advancing Our Understanding of Race-related Stressors. J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 2018, 59, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Annu. Rev. Public Heal. 2019, 40, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A.; Vu, C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Heal. Serv. Res. 2019, 54, 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borrell, C.; Muntaner, C.; Gil-González, D.; Artazcoz, L.; Rodríguez-Sanz, M.; Rohlfs, I.; Pérez, K.; García-Calvente, M.; Villegas, R.; Álvarez-Dardet, C. Perceived discrimination and health by gender, social class, and country of birth in a Southern European country. Prev. Med. 2010, 50, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, B.K.; Kolody, B.; Vega, W.A. Perceived Discrimination and Depression among Mexican-Origin Adults in California. J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 2000, 41, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, S.L.; SELCoH Study Team; Gazard, B.; Williams, D.R.; Frissa, S.; Goodwin, L.; Hotopf, M. Discrimination and common mental disorder among migrant and ethnic groups: Findings from a South East London Community sample. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keys, H.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Foster, J.W.; Minaya, R.Y.B.; Kohrt, B.A. Perceived discrimination, humiliation, and mental health: A mixed-methods study among Haitian migrants in the Dominican Republic. Ethn. Health 2014, 20, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N.; Williams, D.R. Racial Discrimination and Racial Disparities in Health, 1st ed.; Oxford Handbooks Online: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schunck, R.; Reiss, K.; Razum, O. Pathways between perceived discrimination and health among immigrants: Evidence from a large national panel survey in Germany. Ethn. Heal. 2014, 20, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishehgar, S.; Gholizadeh, L.; Di Giacomo, M.; Davidson, P.M. The impact of migration on the health status of Iranians: An integrative literature review. BMC Int. Heal. Hum. Rights 2015, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urzúa, A.; Cabrera, C.; Carvajal, C.C.; Caqueo-Urízar, A. The mediating role of self-esteem on the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health in South American immigrants in Chile. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.B.; Feinstein, L.; Vines, A.I.; Robinson, W.R.; Haan, M.N.; Aiello, A.E. Perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among US Latinos: The modifying role of educational attainment. Ethn. Heal. 2017, 24, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, D.; Seron, E.; Yzerbyt, V.; Herman, G. Perceived group and personal discrimination: Differential effects on personal self-esteem. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urzúa, A.; Ferrer, R.; Olivares, E.; Rojas, J.; Ramírez, R. El efecto de la discriminación racial y étnica sobre la autoestima individual y colectiva según el fenotipo autoreportado en migrantes colombianos en Chile. Ter. Psicológica 2019, 37, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Liebkind, K.; Perhoniemi, R. Perceived discrimination and well-being: A victim study of different immigrant groups. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 16, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesch, G.S.; Turjeman, H.; Fishman, G. Perceived Discrimination and the Well-being of Immigrant Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2007, 37, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevillano, V.; Basabe, N.; Bobowik, M.; Aierdi, X. Health-related quality of life, ethnicity and perceived discrimination among immigrants and natives in Spain. Ethn. Heal. 2014, 19, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urzúa, A.; Ferrer, R.; Godoy, N.; Leppes, F.; Trujillo, C.; Osorio, C.; Caqueo-Urízar, A. The mediating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being in immigrants. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urzúa, A.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Henríquez, D.; Domic, M.; Acevedo, D.; Ralph, S.; Reyes, G.; Tang, D. Ethnic Identity as a Mediator of the Relationship between Discrimination and Psychological Well-Being in South—South Migrant Populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urzúa, A.; Henríquez, D.; Caqueo-Urízar, A. Affects as Mediators of the Negative Effects of Discrimination on Psychological Well-Being in the Migrant Population. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 602537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urzúa, A.; Leiva-Gutiérrez, J.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Vera-Villarroel, P. Rooting mediates the effect of stress by acculturation on the psychological well-being of immigrants living in Chile. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kessler, R.C.; Mickelson, K.D.; Williams, D.R. The Prevalence, Distribution, and Mental Health Correlates of Perceived Discrimination in the United States. J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 1999, 40, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Schieman, S.; Fazio, E.M.; Meersman, S.C. Stress, Health, and the Life Course: Some Conceptual Perspectives. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfield, R.; Linton, R.; Herskovits, M.J. Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation. Am. Anthr. 1936, 38, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. Globalisation and acculturation. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2008, 32, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekteshi, V.; Kang, S.-W. Contextualizing acculturative stress among Latino immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Ethn. Health 2020, 25, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S. Latinos, Acculturation, and Acculturative Stress: A Dimensional Concept Analysis. Policy Politi Nurs. Pr. 2007, 8, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, A.; Piña-Watson, B. Acculturative Stress and Bicultural Stress, 1st ed.; Oxford Handbooks Online: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W.; Kim, U.; Power, S.; Young, M.; Bujaki, M. Acculturation Attitudes in Plural Societies. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 38, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M.Y.; Gordon, K.H.; Minnich, A.M. An examination of the relationships between acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and eating disorder symptoms among ethnic minority college students. Eat. Behav. 2018, 28, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revollo, H.-W.; Qureshi, A.; Collazos, F.; Valero, S.; Casas, M. Acculturative stress as a risk factor of depression and anxiety in the Latin American immigrant population. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2011, 23, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirin, S.R.; Ryce, P.; Gupta, T.; Rogers-Sirin, L. The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: A longitudinal investigation. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, A.; López, M. Ansiedad y modos de aculturación en la población inmigrante. Apunt. De Psicol. 2008, 26, 399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Urzúa, A.; Heredia, O.; Caqueo-Urízar, A. Salud mental y estrés por aculturación en inmigrantes sudamericanos en el norte de Chile. Revista médica de Chile 2016, 144, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hun, N.; Urzúa, A.; Henríquez, D.T.; López-Espinoza, A. Effect of Ethnic Identity on the Relationship Between Acculturation Stress and Abnormal Food Behaviors in Colombian Migrants in Chile. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hun, N.; Urzúa, A.; López-Espinoza, A. Anxiety and eating behaviors: Mediating effect of ethnic identity and acculturation stress. Appetite 2021, 157, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Nam, S.; Redeker, N.S.; Shebl, F.M.; Dixon, J.; Jung, T.H.; Whittemore, R. The effects of acculturation and environment on lifestyle behaviors in Korean immigrants: The mediating role of acculturative stress and body image discrepancy. Ethn. Heal. 2019, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.C.; Schwartz, S.J.; Zamboanga, B.L. Acculturative Stress Among Cuban American College Students: Exploring the Mediating Pathways Between Acculturation and Psychosocial Functioning. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 2862–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Driscoll, M.W.; Voell, M. Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: A moderated mediational model. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2012, 18, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barbieri, E.N.G.; Baleisan, C.P.; Rodríguez, F. Inmigración reciente de colombianos y colombianas en Chile: Sociedades plurales, imaginarios sociales y estereotipos. Estudios Atacameños 2019, 62, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, E.N.G.; De Chile, U.; Suárez, G.G. Integración y exclusión de inmigrantes colombianos recientes en Santiago de Chile: Estrato socioeconómico y “raza” en la geocultura del sistema-mundo. Papeles de Población 2017, 23, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; Yu, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health. J. Heal. Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krieger, N.; Smith, K.; Naishadham, D.; Hartman, C.; Barbeau, E.M. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1576–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vilagut, G.; Valderas, J.M.; Ferrer, M.; Garin, O.; López-García, E.; Alonso, J. Interpretation of SF-36 and SF-12 questionnaires in Spain: Physical and mental components. Med. Clin. 2008, 130, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alegría, M.; Canino, G.; Shrout, P.E.; Woo, M.; Duan, N.; Vila, D.; Torres, M.; Chen, C.-N.; Meng, X.-L. Prevalence of Mental Illness in Immigrant and Non-Immigrant U.S. Latino Groups. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Agredo-Zuñiga, R.; Jerez-Valderrama, A. Confiabilidad y valores normativos preliminares del cuestionario de salud SF-12 (Short Form 12 Health Survey) en adultos Colombianos. Rev. Salud Pública 2010, 12, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ugalde-Watson, K.; Smith-Castro, V.; Moreno-Salas, M.; Rodríguez-García, J.M. Estructura, correlatos y predictores del estrés por Aculturación. El caso de personas refugiadas colombianas en Costa Rica. Univ. Psychol. 2010, 10, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urzúa, A.; Henríquez, D.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Smith-Castro, V. Validation of the brief scale for the evaluation of acculturation stress in migrant population (EBEA). Psicologia Reflexão e Crítica 2021, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, L.; Muthen, B. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stride, C.B.; Gardner, S.; Catley, N.; Thomas, F. Mplus Code for Mediation, Moderation, and Moderated Mediation Models. Available online: http://www.offbeat.group.shef.ac.uk/FIO/models_and_index.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2017).

- Beauducel, A.; Herzberg, P.Y. On the Performance of Maximum Likelihood Versus Means and Variance Adjusted Weighted Least Squares Estimation in CFA. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2006, 13, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B. Update to core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2017, 13, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ato, M.; Vallejo, G. Los efectos de terceras variables en la investigación psicológica. Anales de Psicología 2011, 27, 550–561. [Google Scholar]

- Zainiddinov, H. Racial and ethnic differences in perceptions of discrimination among Muslim Americans. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2016, 39, 2701–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontkowski, U.; Florack, A.; Hoelker, P.; Obdrzálek, P. Predicting acculturation attitudes of dominant and non-dominant groups. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2000, 24, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuche, A. Entre utopías y realidades: ¿qué significados le otorga un/a colombiano/a al hecho de vivir en Santiago de Chile? Rev. Búsquedas Políticas 2015, 4, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverri, M. Otredad racializada en la migración forzada de afrocolombianos a Antofagasta (Chile). Nómadas 2016, 45, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cervantes, R.C.; Gattamorta, K.A.; Berger-Cardoso, J. Examining Difference in Immigration Stress, Acculturation Stress and Mental Health Outcomes in Six Hispanic/Latino Nativity and Regional Groups. J. Immigr. Minor. Heal. 2018, 21, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urzúa, A.; Basabe, N.; Pizarro, J.J.; Ferrer, R. Afrontamiento del estrés por aculturación: Inmigrantes latinos en Chile. Univ. Psychol. 2018, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mewes, R.; Asbrock, F.; Laskawi, J. Perceived discrimination and impaired mental health in Turkish immigrants and their descendents in Germany. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 62, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondolo, E.; Halen, N.B.V.; Pencille, M.; Beatty, D.; Contrada, R.J. Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | Range | Min | Max | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived discrimination | ||||||

| Racial discrimination | 0.55 | 0.70 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 837 |

| Ethnic discrimination | 0.72 | 0.71 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 930 |

| Acculturation stress | 3.07 | 0.91 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 744 |

| Health status | ||||||

| Physical health | 75.29 | 17.88 | 79 | 21 | 100 | 942 |

| Mental health | 70.92 | 17.42 | 83 | 17 | 100 | 953 |

| Models | Parameters | χ2 | DF | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSEA CI 90% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Superior | ||||||||

| ED | 40 | 783.767 | 35 | 0.00 | 0.943 | 0.927 | 0.148 | 0.140 | 0.158 |

| RD | 40 | 691.463 | 35 | 0.00 | 0.965 | 0.956 | 0.146 | 0.137 | 0.156 |

| AS | 73 | 544.257 | 74 | 0.00 | 0.980 | 0.975 | 0.081 | 0.075 | 0.087 |

| SF-12 | 52 | 408.221 | 19 | 0.00 | 0.949 | 0.925 | 0.145 | 0.133 | 0.157 |

| M1 | 137 | 2436.596 | 344 | 0.00 | 0.940 | 0.934 | 0.079 | 0.076 | 0.082 |

| M2 | 214 | 3012.959 | 806 | 0.00 | 0.954 | 0.951 | 0.053 | 0.051 | 0.055 |

| Models | Parameters | χ2 | DF | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSEA CI 90% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Superior | ||||||||

| M1 | 137 | 2436.596 | 344 | 0.00 | 0.940 | 0.934 | 0.079 | 0.076 | 0.082 |

| M2 | 214 | 3012.959 | 806 | 0.00 | 0.954 | 0.951 | 0.053 | 0.051 | 0.055 |

| M3 | 94 | 831.929 | 132 | 0.00 | 0.970 | 0.966 | 0.074 | 0.069 | 0.079 |

| M4 | 214 | 3012.959 | 806 | 0.00 | 0.954 | 0.951 | 0.053 | 0.051 | 0.055 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urzúa, A.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Henríquez, D.; Williams, D.R. Discrimination and Health: The Mediating Effect of Acculturative Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105312

Urzúa A, Caqueo-Urízar A, Henríquez D, Williams DR. Discrimination and Health: The Mediating Effect of Acculturative Stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105312

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrzúa, Alfonso, Alejandra Caqueo-Urízar, Diego Henríquez, and David R. Williams. 2021. "Discrimination and Health: The Mediating Effect of Acculturative Stress" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105312

APA StyleUrzúa, A., Caqueo-Urízar, A., Henríquez, D., & Williams, D. R. (2021). Discrimination and Health: The Mediating Effect of Acculturative Stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105312