Inclusion of Gender Views for the Evaluation and Mitigation of Urban Vulnerability: A Case Study in Castellón

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

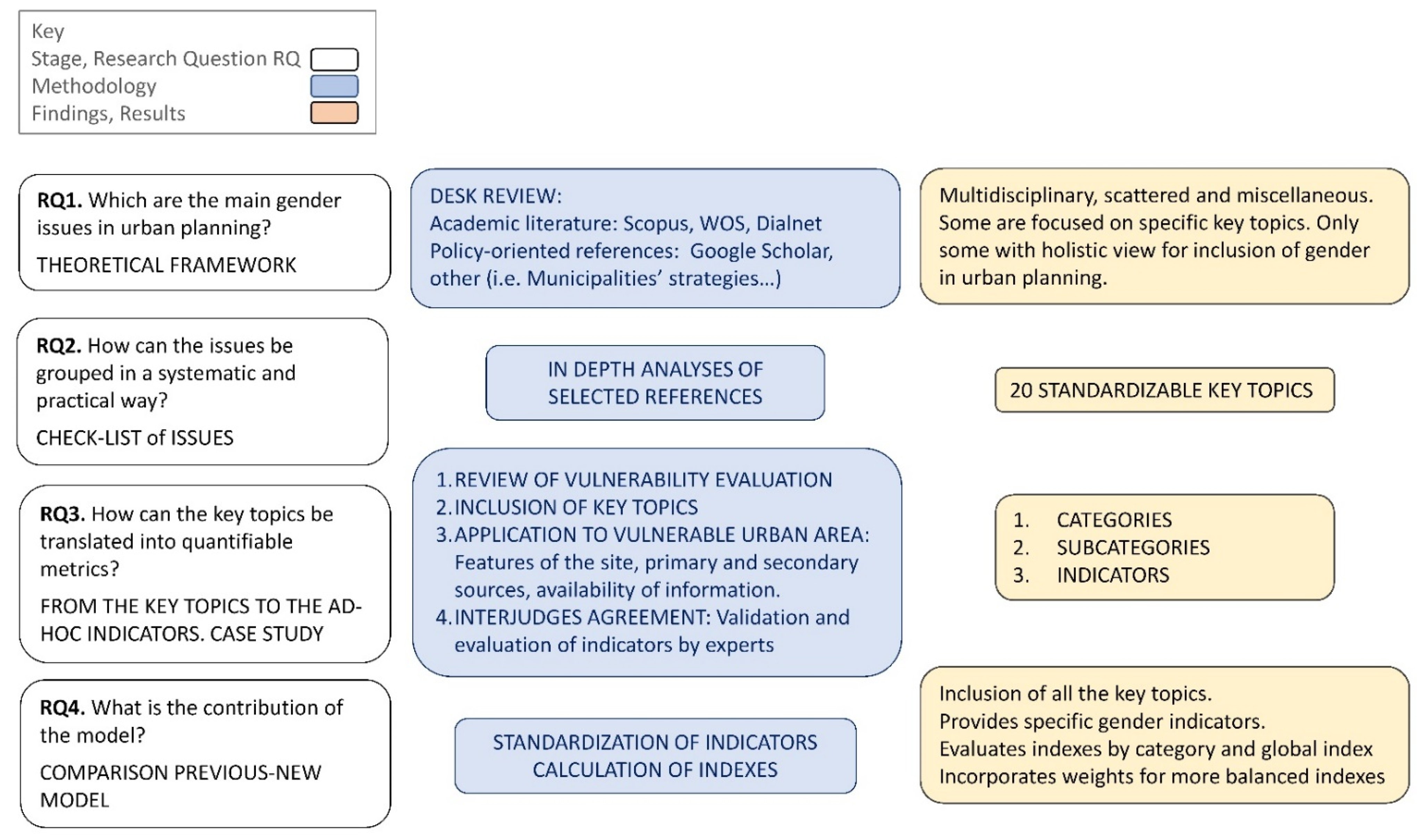

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Key Topics for Gender-Sensitive Urban Design

- Compactness is connected to the form and arrangement of urban areas including spatial design, distribution of land-use subcategories, and transportation networks. A compact city makes it considerably easier to reconcile the requirements of work and family life [57];

- Public open space includes parks and reserves; sport fields; riparian zones, such as streams and riverbanks; greenways and trails; community gardens; street trees; nature conservation areas [58]. These spaces are available for users and where the public life of the city plays out and civic identity is defined [59];

- The perception of safety in public spaces promotes the feeling of security in public spaces, and special attention must be paid to provide adequate lighting in walking paths for pedestrians and walls, fences, and stairs that create hidden corners with difficult accessibility. According to Chestnutt, linking buildings to outdoor spaces can create amenity value and ensure sufficient options for the appropriation of public spaces [62];

- Walkability and accessibility: The goal is to create infrastructure, urban spaces, and equipment tailored for people’s needs in order to ease pedestrian and autonomous mobility. This refers to wide sidewalks, with differentiation of materials, colors, and textures, railings and ramps in sloped areas, differentiated pedestrian crossings with traffic lights, and benches with shadows. This not only supports people with reduced mobility but also facilitates people’s lives with caregiving and family responsibilities [63];

- Mixed-use planning in terms of urban development where residential, commercial, cultural, institutional, or entertainment uses are physically and functionally integrated and provide pedestrian connections. The goal lies in preserving and/or developing a decentralized distribution of facilities based on measures that promote public service and infrastructure facilities close to public transport stops [64];

- Care facilities and equipment supply is expanded when society recognizes, assumes, and values work derived from gender roles. The goal is to create or improve access to care facilities for dependent people, the elderly, or children, ensuring accessible and affordable services. Additionally, it enables people with care responsibilities to balance these with their work activities;

- Visibility of women: Gendered stereotypes can have the effect of promoting fixed ideas about what women can become and their needs [65]. The aim is to make women visible in cities with measures such as placing names of prominent women in history to streets and squares in the city, promoting equal urban signs, and controlling discriminatory adverts;

- Housing design to improve affordability: Currently, there are different types of families, so housing must be designed according to the particular needs of each family. Various funding and development models as well as different types of housing all guarantee a high level of potential for assimilation of the diversity of user groups [62];

- Energy-efficient housing: The deterioration and lack of insulation in many homes results in higher costs to keep them at a suitable temperature, which is not affordable. The urban agenda of the EU partnership on housing has found that women and, especially low-income and vulnerable groups of women, are more likely to experience energy poverty [66];

- Accessible housing should be seen as a way to facilitate greater autonomy for dependent people, guaranteeing universal accessibility to and inside houses [67];

- Quality housing: Marginalized women are also likely to be impacted by the lack of quality housing. This results in temporary or precarious accommodation [68];

- Disaggregated statistical data by gender are of interest to sociologists and social workers to determine actual statistical results [69]. Information should be disaggregated based on sex to compare and contrast the situation that men and women, and boys and girls, experience in terms of accessibility, opportunities, roles, and responsibilities;

- Violence and security: Violence against women is a violation of human rights. Municipal plans could be revised to include steps to limit violence against women by providing shelter and refuge and support for organizations offering special assistance to women [3]. Security, related to the influence of police interventions on human safety and other factors contributing to the well-being of neighborhoods, should be incremented [70,71];

- Social housing involves ensuring allocation and other resources based on balanced social priorities. Women with low incomes are disproportionately represented, as they are often the head of households in single-parent families. Thus, poor women and single parents are more reliant on social housing than men [72];

- Paid and unpaid work: Urban planning strategies are often based on a unilateral vision of the economy; that is, it only measures the paid work of employed people who drive a car to get to work and during regular working hours. In most cases, care responsibilities or unpaid work are not taken into account. Plans should include aid for unpaid work [73];

- Social subsidies: Economic aid is available for basic needs (food, hygiene, and school canteens), housing expenses (rent, energy poverty, water, electricity, and gas supply), other expenses (nursery schools, glasses, appliances), and job training. Data regarding beneficiaries of social service aid inclusion indicate there is a vulnerable population of women who take care of dependent people and do not have access to these aid programs [66];

- Level of education: Urbanization involves major changes in the way people work and live. It offers opportunities for improved standards of living, higher life expectancy, and higher literacy levels [73]. Certain groups of women are particularly vulnerable, especially those with low levels of education and skills.

- Housing market: The cost of accommodation in inadequate and overcrowded housing takes up a disproportionate part of low-income people’s earnings [73]. Housing is a major factor in urban poverty affecting women;

- Women’s and men’s participation in formal and informal decision making is uneven. Gender equality must be guaranteed at all levels, because women are underrepresented not only in the political scene but also in decision making within their villages, the private sector, and in civil society (OCDE, 2020).

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References, Year, Country, Type of Document | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Jacobs, 1961 [74], US, (B) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hayden, 1980 [23], US, (A) | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Kennedy, 1981 [75], Germany, (A) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sarmento and Pareja, 2002 [76], Brazil, (A) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sánchez de Madariaga, 2004 [30], Spain, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Venturi and Scott, 2004 [77], US, (B) | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| García-Ramón et al., 2004 [17], Spain, (A) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Federation Canadian Municipalities, 2004 [78], Canada, (R) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Sánchez de Madariaga et al., 2005 [68], Spain, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Cucurella et al., 2006 [79], Spain, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Amin 2006 [80], Afghanistan, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Palestine (Gaza), Qatar, Syria, Uzbekistan (B) | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sweet and Ortiz, 2010 [8], Mexico, US, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Curran, 2010 [81], US, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Muxí and Giocoletto, 2011 [64], Spain, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Muxí et al., 2011 [82], Spain, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Turner, 2011 [83], UK, (A) | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Gutiérrez, 2011 [84], Spain, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Tacoli, 2012 [73], UK, (R) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Ciocoletto, 2012 [85], Spain (R) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Tummers, 2013 [86], Italy (A) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kneeshaw & Norman, 2014 [65], US, (R) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Gregorio, 2014 [31], Spain, (A) | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ciocoletto, 2014 [87], Spain, (DT) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Tummers, 2015 [88], France, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Majedi, 2015 [89], India, (A) | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Sánchez de Madariaga and Neuman, 2016 [11], Spain, (A) | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| González, 2016 [66], Spain, (R) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Schreiber and Carius, 2016 [90], Spain, (BC) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Mateo-Cecilia, 2016 [91], Spain, (A) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Jazmin, 2016 [92], Argentina, (A) | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Beebeejaun, 2017 [93], UK, (A) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Atehortua, 2017 [8], Venezuela, (BC) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Martin, 2017 [94], Spain (BC) | x | |||||||||||||||||||

| Valdivia, 2018 [21], Spain (A) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Álvarez and Gómez, 2018 [69], Spain, (R) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Arora, 2018 [95], Saudi Arabia, (R) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Thi-Thanh-Hien, 2019 [96], Vietnam, (A) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Gargiulo et al., 2020 [38], Spain (A) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Arefian and Moeini, 2020 [97], Switzerland, (B) | x | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sepe, 2020 [10], Italy, (A) | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

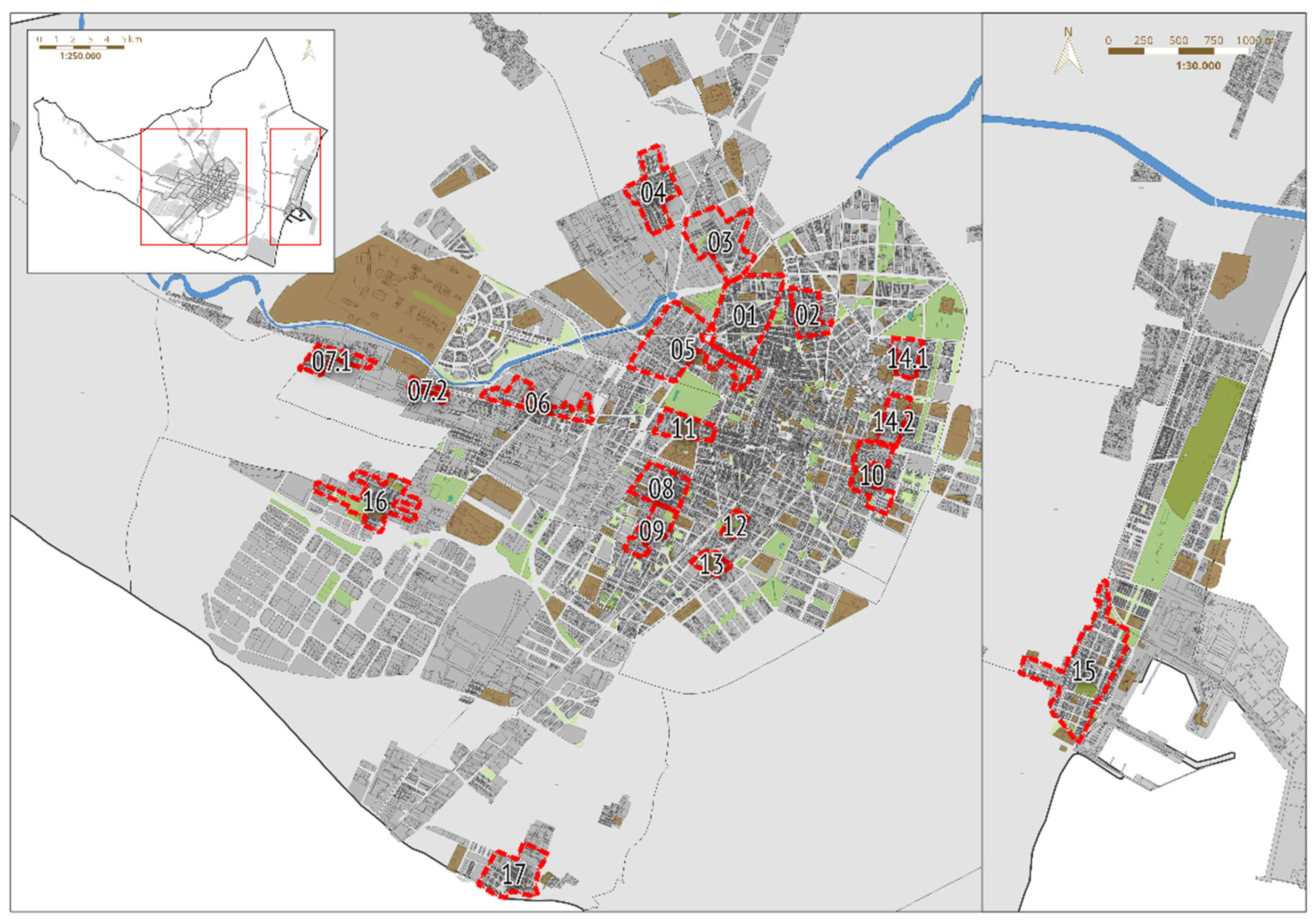

3.2. Case Study

- Seventeen new quantifiable indicators (in bold) were added because no specific indicators considered gender explicitly in the previous model [52].

- Four new indicators were added (“unsafe perceived sites”, “accessibility in housing”, and “gender violence” in subcategories U4, U6, and B3 and SD2, respectively). These indicators, for instance, will help detect unsafe places due the lack of lighting, vegetation density, or hidden spots in public spaces.

- Six new indicators linked with demographic issues were added, because disaggregated data by genre were perceived as essential (indicators in subcategories SD1 and SE1 and SE3, accounting specifically for women (according to the key topic 1). For instance, “population over 65 years” was replaced with the new indicator “women over 65 years”.

- Seven new specific gender-sensitive indicators were proposed to incorporate three subcategories that had not been included in the previous model [52]: U7, U8, and B1, (represented in 62%, 42%, and 40% in the analyzed literature, respectively). For instance, subcategory U7 “care facilities”, includes the indicators “children care facilities”, “elderly care facilities”, and “disabled care facilities”.

- Eight indicators under 50% of agreement were rejected. These are highlighted in the shaded cells (see Table 2): U8.15. Women street names; B1.17 Housing variety; B2.19. Renewable energy; SD1.31. Women under 15; SD1.32. Aging rating 65/15; SD1.33. Women aging rating 65/15; SD2.37. Police interventions in traffic; SD2.38. Police interventions others. Indicator B1.17, representing the subcategory Housing design, was inferred from the literature but did not result in importance according to the experts.

- Some indicators reached a perfect agreement (100%): U2.2. Green areas; U3.6. Proximity to public transport; U4.7. Unsafe perceived sites; B3.20. Building accessibility.

- From the response to the open question, Judge number 7 suggested to include “Lighting”. This aspect had already been included in subcategory U4. Perception of security, specifically in the indicator “Perception of unsafe sites”.

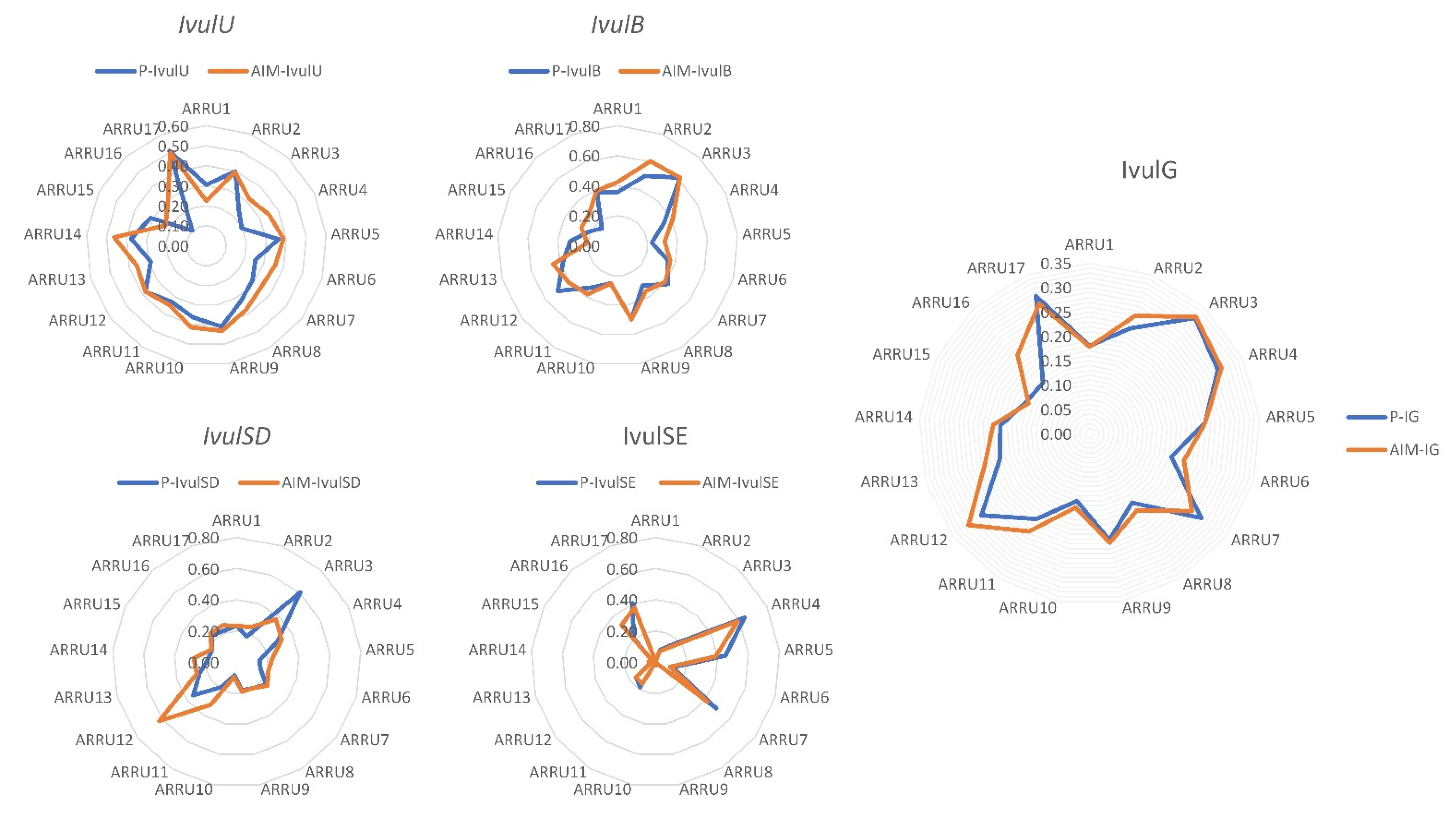

3.3. Evaluating the Applicability of the Model

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, A/RES/70/1: Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 23 December 2016, A/RES/71/256: New Urban Agenda. Available online: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/71/256 (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Miralles-Guasch, C.; Martínez Melo, M.; Marquet, O. A gender analysis of everyday mobility in urban and rural territories: From challenges to sustainability. Gend. Place Cult. 2015, 23, 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huning, S. From feminist critique to gender mainstreaming—And back? The case of German urban planning. Gend. Place Cult. 2020, 27, 944–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irschik, E.; Kail, E. Vienna: Progress towards a fair shared city. In Fair Shared City; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2013; Chapter 12; p. 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I.; Novella, I. Chapter 7: A new generation of gender mainstreaming in spatial and urban planning under the new international framework f policies for sustainable development. In Gendered Approaches to Spatial Development in Europe. Perspectives, Similarities, Differences; Zibell, B., Damyanovic, D., Sturm, U., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2019; pp. 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet, E.; Ortiz, S. Planning Responds to Gender Violence: Evidence from Spain, Mexico and the United States. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2129–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez de Madariaga, I.; Roberts, M. Fair Shared Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atehortua, J.V. Barrio Women’s Gendering Practices for Sustainable Urbanism in Caracas, Venezuela. Women, urbanization and sustainability: Practices of survival, adaptation and resistance. In Gender Development and Social Change Series; Lacey, A., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M. Regenerating places sustainably: The healthy urban design. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I.; Neuman, M. Mainstreaming Gender in the city. Town Plan. Rev. 2016, 87, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, J. Instrumentos para el análisis y políticas para la acción. In Proceedings of the Foro de Debates: Ciudad y Territorio. Jornada La Vulnerabilidad Urbana en España, Madrid, Spain, 30 June 2011; Ministerio de Fomento: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Antón, F.; Cortés, L.; Martínez, C.; Navarrete, J. La exclusión residencial en España. In Políticas y Bienes Sociales. Procesos de Vulnerabilidad y Exclusión Social; Arriba González, A., Ed.; Fundación Foessa: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S. The just city. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2014, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, F.; Paterson, S. Stories from the Front Lines: Making Sense of Gender Mainstreaming in Canada. Politics Gend. 2018, 14, 208–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.; Levy, C. A Theory and Methodology of Gender Planning: Meeting Women’s Practical and Strategic Needs; Development Planning Unit (DPU), University College: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ramón, M.D. Para no excluir del estudio a la mitad del género humano. Un desafío pendiente geografía humana. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 1989, 9, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté, A.; Rodríguez, J.; Díaz, M.A. Mujeres, Espacio y Sociedad. Hacia Una Geografía del Género; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Dowell, L. Género, Identidad y Lugar. Un Estudio de las Geografías Feministas; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bondi, L.; Rose, D. Constructing gender, constructing the urban: A review of Anglo-American feminist urban geography. Gend. Place Cult. 2003, 10, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, C. Ciudad y género. Una ciudad más justa: El género y la planificación. In La Ciudad Inclusiva; Balbo, M., Jordán, R., Simioni, D., Eds.; Cuadernos de la CEPAL 88; Nacionales Unidas: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2003; pp. 237–258. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/27814/S2003002_es.pdf;jsessionid=8341F69732A246CA61 (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Horelli, I. Engendering urban planning in different contexts–successes, constraints and consequences. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1779–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiro, M.; López, C. Parametrizar y Sistematizar, o cómo Incorporar la Perspectiva de Género en el Diseño Urbano. 2015. Available online: https://ruc.udc.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/2183/17452/mccl_IIIXUGX_150602.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Hayden, D. What would a non-sexist city be like? speculations on housing, urban design, and human work. Signs 1980, 5, 170–187. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3173814 (accessed on 2 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Carpio-Pinedo, J.; de Gregorio, S.; Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Gender mainstreaming in urban planning: The potential of geographic information systems and open data sources. Plan. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, B. Del urbanismo androcéntrico a la ciudad cuidadora. Habitat Soc. 2018, 11, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greed, C. Género y planificación del territorio¿Un mismo tema? In Forúm Internacional de Planificación del Territorio Desde una Perspectiva de Género; Fundació Maria Aurèlia Capmany: Barcelona, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, A. From equal opportunities to gender awareness in strategic spatial planning: Reflections based on Swedish experiences. Town Plan. Rev. 2006, 77, 507–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C. Estadístiques sota Sospita: Proposta de Nous Indicadors des de l’Experiència Femenina; Institut Català de les Dones: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; Available online: https://dones.gencat.cat/web/.content/03_ambits/docs/publicacions_eines07.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Infraestructuras para la vida cotidiana y calidad de vida. Ciudades 2004, 8, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorio, S. Factores relevantes en la introducción del urbanismo con perspectiva de género en Viena. In La Ciudad Viva, Derecho a la Vivienda, Derecho a la Ciudad; Consejeria de Fomento y Vivienda: Junta de Andalucía, Spain, 2014; Volume 7, pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Damyanovic, D.; Reinwald, F.; Weikmann, A. Gender Mainstreaming in Urban Planning and Urban Development; Irschik, E., Kail, E., Klimmer-Pöllentzer, A., Nuss, A., Poscher, G., Schönfeld, M., Winkler, A., Eds.; Vienna City Council: Vienna, Austria, 2013. Available online: https://www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/studien/pdf/b008358.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Whitzman, C.; Canuto, M.; Binder, S. Women’s Safety Awards 2004: A Compendium of Good Practices. Available online: www.femmesetvilles.org (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Nguyen, T.M.; van Nes, A. Identifying the spatial parameters for differences in gender behaviour in built environments: The flâneur and flâneuse of the 21st century. TRIA 2013, 10, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, A. Gender mainstreaming, urban planning and design processes in Greece. In Engendering Cities: Designing Sustainable Spaces for All; Sánchez de Madariaga, I., Neuman, M., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, W. What to Do about Women’s Safety in Parks: From A to Y; Greig, C., Ed.; Women’s Design Service: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liam Riley, L. Malawian urbanism and urban poverty: Geographies of food access in Blantyre. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2020, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, I.; Garcia, X.; Benages-Albert, M.; Martinez, J.; Pfeffer, K.; Vall-Casas, P. Women’s safety perception assessment in an urban stream corridor: Developing a safety map based on qualitative GIS. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Rivera, L. A safer housing agenda for women: Local urban planning knowledge and women’s grassroots movements in Medellín, Colombia. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, L.; Rönnblom, M. ‘I don’t think we’ll ever be finished with this’: Fear and safety in policy and practice. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2664–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitzman, C. Stuck at the front door: Gender, fear of crime and the challenge of creating safer space. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 2715–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Escalante, S.; Gutiérrez Valdivia, B. Planning from below: Using feminist participatory methods to increase women’s participation in urban planning. Gend. Dev. 2015, 23, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, D.; Zombori, E. Engendering cities: International dimensions from Aotearoa, New Zealand. Town Plan. Rev. 2016, 87, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, C.; Grant-Smith, D.; Osborne, N. Women in planning in the twenty-first century. Aust. Plan. 2017, 54, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greed, C.H. Planning for women and other disenabled groups, with reference to the provision of public toilets in Britain. Environ. Plan. A 1996, 28, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, B.F.; Creutzig, F. Lifting peripheral fortunes: Upgrading transit improves spatial, income and gender equity in Medellin. Cities 2017, 70, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussié, R. Childcare services in cities: Challenges and emerging solutions for women informal workers and their children 21. Environ. Urban. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Dorantes, L.; Soto Villagrán, P. A review on the influence of barriers on gender equality to access the city: A synthesis approach of Mexico City and its Metropolitan Area. Cities 2020, 96, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, C. Travel choice reframed: “deep distribution” and gender in urban. Environ. Urban. 2013, 25, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestbro, D.U.; Horelli, L. Design for gender equality: The history of co-housing ideas and realities. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.F. Segregated from the City: Women’s Spaces in Islamic Movements in Pakistan. City Soc. 2019, 31, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruá, M.J.; Huedo, P.; Civera, V.; Agost-Felip, R. A simplified model to assess vulnerable areas for urban regeneration. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 46, 101440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.; Lauf, E. Reliability in Cross-national Content Analysis. J. Mass. Commun. Q. 2002, 79, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremades, R. Validación de un instrumento para el análisis y evaluación de webs de bibliotecas escolares mediante el acuerdo interjueces. Investig. Bibl. 2017, 31, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dubé, J.E. Evaluación del acuerdo interjueces en investigación clínica. Breve introducción a la confiabilidad interjueces. Rev. Argent. Clin. Psicol. 2008, 1, 75–80. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2819/281921796008.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Actis di Pasquale, E.; Balsa, J. Interval Linear Scaling Technique: Proposal for Standardization Applied to the Measurement of Social Well-Being Levels. Rev. Métodos Cuantitativos Para Econ. Empresa 2017, 23, 164–193. Available online: https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/RevMetCuant/article/view/269 (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Abdullahi, S.; Pradhan, B. Urban compactness assessment. In Spatial Modeling and Assessment of Urban Form; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, U.; Shah, A. Urban Green Spaces and an Integrative Approach to Sustainable Environment. J. Environ. Prot. 2011, 2, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; de Barros, A.G.; Kattan, L. Public transportation and sustainability: A review. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I.; de Gregorio, S.; Novella, I. Perspectiva de Género en las Directrices de Ordenación Territorial (DOT) del País Vasco. Propuestas de Acción 2019. Departamento de Medio Ambiente y Política Territorial del Gobierno Vasco. Available online: https://www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/revision_dot/es_def/adjuntos/Perspectiva%20de%20G%C3%A9nero%20en%20las%20DOT%20(ISdM).pdf (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Chestnutt, R.; Ganssauge, K.; Willecke, B.; Baranek, E.; Bock, S.; Huning, S.; Schröder, A. Gender Mainstreaming in Urban Development; Christiane Droste: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Muxí, Z.; Ciocoletto, A. La Ley de Barrios en Cataluña: La perspectiva de género como herramienta de planificación. Feminismo/s. 2011, 17, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Kumar, U. Taxonomy of urban mixed land use planning. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneeshaw, S.; Norman, J. Gender Equality Cities URBACT III; URBAC: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pijuán, I. Desigualdad de Género y Pobreza Energética. Un Factor de Riesgo Olvidado; L’Associació Catalana d’Enginyeria Sense Fronteres: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://esf-cat.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/ESFeres17-PobrezaEnergeticaiDesigualdadGenero.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Serrano, B. Género y Política Urbana. Available online: http://www.five.es/descargas/archivos/urbanismo/genero_y_politica_urbana_2017.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I.; Casado, E.; Gómez, C. Los Desafíos de la Conciliación Entre Vida Laboral y Vida Familiar en el Siglo XXI; Fundación Ortega y Gasset, Biblioteca Nueva: Madrid, Spain, 2005; pp. 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, E.; Gómez, C.J. La incorporación de la perspectiva de género en el Plan General Estructural de Castelló: Objetivos, método, acciones y hallazgos. Hábitat Soc. 2018, 11, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affleck, R.T.; Gardner, K.; Aytur, S.; Carlson, C.; Grimm, C.; Deeb, E. Sustainable Infrastructure in Conflict Zones: Police Facilities’ Impact on Perception of Safety in Afghan Communities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collectiu Punt 6. The Everyday Life of Women Nightshift Workers in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area. The Night Mobility in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area. Available online: http://www.punt6.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Nocturnas (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Kneeshaw, S.; Norman, J. Gender Equal Cities. URBACT Knowledge Hub. 2019. Available online: https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/urbact-genderequalcities-edition-pages-web.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Taccoli, C. Urbanisation, Gender and Urban Poverty. Paid Work and Unpaid Carework in the City. International Institute for Environment and Development 2012. (IIED, London) and United Nations Population Fund (UNPF, New York). Urbanization and Emerging Population Issues. Working Paper 7. Available online: http://pubs.iied.org/10614IIED.htmlInclusive and sustainable Urban planning (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Jacobs, J. Muerte y Vida en las Grandes Ciudades, 2nd ed.; Capitán Swing: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M. Towards a rediscovery of feminine principles in Architecture and Planning. Womens Stud. Int. Quart. 1981, 4, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, D.P.G.; Bankhardt, F.A. Inclusive cities for women: From women’s history to transformations in the city space. NODO 2002, 14, 86–102. [Google Scholar]

- Venturi, R.; Scott Brown, D. Architecture as Signs and Systems: For a Mannerist Time; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) and the City of Montreal (Femmes et Ville Program). A City Tailored to Women. The Role of Municipal Governments in Achieving Gender Equality. 2004. Available online: https://fcm.ca/sites/default/files/documents/resources/guide/a-city-tailored-to-women-the-role-of-municipal-governments-in-achieving-gender-equality-wilg.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Cucurella, A.; Garcia-Ramon, M.D.; Baylina, M. Gender, age and design in a new public space in a mediterranean town: The Parc dels Colors in Mollet del Valles (Barcelona). Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2006, 13, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A. The good city. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, W.; Breitbach, C. Notes on women in the global city: Chicago. Gend. Place Cult. 2010, 17, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muxí, Z.; Casanovas, R.; Ciocoletto, A.; Fonseca, M.; Gutiérrez, B. ¿Qué aporta la Perspectiva de Género al Urbanismo? Feminismo/s 2011, 17, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. Urban mass transit, gender planning protocols and social sustainability. The case of Jakarta. Res. Transp. Econ. 2011, 34, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Mozo, M.E. Arquitectura y el Urbanismo con Perspectiva de Género. Feminismo/s; Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ciocoletto, A. Estudios Urbanos, Género y Feminismo. Teorías y Experiencias; Generalitat de Catalunya, Institut Català de les Dones: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L. Urbanism of proximity: Gender-expertise or shortsighted strategy? Re-introducing Gender Impact Assessments in spatial planning. TRIA 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocoletto, A. Urbanismo Para la Vida Cotidiana. Herramientas de Análisis y Evaluación Urbana a Escala de Barrio Desde la Perspectiva de Género. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L. Gender stereotypes in the practice of urbanism. Trav. Genre Soc. 2015, 33, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majedi, H.M.; Alireza, A.; Mehrabi, Z.; Mosharzadeh, Z. Identifying effective factors of women’s participation in urban development projects. Bagh E Nazar 2015, 12, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, F.; Carius, A. Ciudades inclusivas: Planeamiento urbano para la diversidad y la cohesión social. In La Situación del Mundo 2016: Informe Anual del Worldwatch Institute sobre Progreso Hacia una Sociedad Sostenible; Icaria Ediciones: Vilassar de Dalt, Spain, 2016; pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo-Cecilia, C.; Rubio-Garrido, A.; Serrano-Lanzarote, B. Some notes on how to introduce the gender perspective in urban policies. The case of the Valencian community (Spain). TRIA 2016, 17, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazmín, M. Metropolitan dynamics in the XXIst century: Some elements to think about gender and sexuality in urban spaces. TRIA 2015, 16, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebeejaun, Y. Gender, urban space, and the right to everyday life. J. Urban Aff. 2017, 39, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.M. Human building. Settlements for and from People. Conclusions on Six Case-Studies. Kultur 2017, 4, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A. Mainstreaming Gender in Urban Planning Gender and Mobility, Velo-City, Access to Life. Kapsarc. 2018. Available online: https://ecf.com/sites/ecf.com/files/Arora_A._Mainstreaming_Gender_in_Urban_Planning.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Thi-Thanh-Hien, P.; Danielle Labbé, D.; Lachapelle, U.; Étienne Pelletier, E. Perception of park access and park use amongst youth in Hanoi: How cultural and local context matters. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefian, F.F.; Moeini, S.H.I. Urban Heritage Along the Silk Roads. A Contemporary Reading of Urban Transformation of Historic Cities in the Middle East and Beyond; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz-Moscardó, M.; Fuertes, I. La feminización de la pobreza; Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I: Castellón, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, I. Quality of life in poor neighborhoods through the lenses of the capability approach—A case study of a deprived area of Łódź City centre. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bernal, D.; Huedo, P.; Babiloni, S.; Braulio, M.; Carrascosa, C.; Civera, V.; Ruá, M.J.; Agost-Felip, M.R. (INPRU-CS). Estudio y Propuesta de Áreas de Rehabilitación, Regeneración y Renovación Urbana, con Motivo de la Tramitación del Plan General Estructural de Castellón de la Plana. Available online: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/urbanismo/TOMO_I.pdf; https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/urbanismo/TOMO_II.pdf; https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/urbanismo/TOMO_III.pdf; https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/urbanismo/TOMO_IV.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2020).

| ARRU | Name | ARRU | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Castalia-La Guinea | 10 | Catorce junio-Grapa |

| 2 | Alcalde Tarrega | 11 | Plaza Toros |

| 3 | Tombatossals | 12 | Constitucion |

| 4 | San Agustin-San Marcos | 13 | Sequiol |

| 5 | Farola-Ravalet | 14 | Rafalafena |

| 6 | Cremor | 15 | Grao |

| 7 | Carretera la Alcora | 16 | San Lorenzo |

| 8 | Gran Via | 17 | Perpetuo Socorro-La Union |

| 9 | Parque del Oeste |

| Category | Subcategory | Indicator | Definition; Calculation; Source | Judges Evaluation | Agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | σ | I+VI | ||||

| U. Urban public space | U1. Compactness | 1. Building density | Dwellings per hectare on urban land; number of dwellings/total Has; (5) | 4.2 | 0.9 | 88.9% |

| U2. Urban public space | 2. Green areas | Green areas per inhabitant on urban land; m2 green areas/number inhabitants in area; (2, 5) | 4.6 | 0.5 | 100.0% | |

| 3. Day sound level | Percentage of the population exposed to noise levels higher than 55 decibels for the day period. (Population exposed to >55 dBA/total population) × 100; (2) | 3.7 | 1.0 | 66.7% | ||

| 4. Night sound level | Percentage of the population exposed to noise levels higher than 45 decibels for the day period. (Population exposed to >45 dBA/total population) × 100; (2) | 4.0 | 1.0 | 66.7% | ||

| 5. Abandoned buildings | Buildings’ potential buildability abandoned or in poor conditions; number of abandoned buildings; (3, 4) | 4.3 | 0.8 | 77.8% | ||

| U3. Mobility– Public transport | 6. Proximity to public transport | Percentage of population with coverage to one or more public transport stops and a cyclist network (300 m to urban bus, tram, taxi, or bike stops); (m2 of urban land without coverage/total area) × 100; (2, 4) | 4.8 | 0.4 | 100.0% | |

| U4. Perception of security | 7. Unsafe perceived sites | Area of unsafe perceived sites due to the lack of lighting, vegetation density, or existence of hidden spots (m2 of unsafe perceived sites/total area) × 100; (2, 3) | 4.8 | 0.4 | 100.0% | |

| 8. Vacant lots | Percentage of total vacant lots of urban area; m2 vacant lots/total area) × 100; (3, 4) | 4.2 | 0.7 | 77.8% | ||

| U5. Accessibility | 9. Accessibility in public space | Percentage of accessible footpath, meaning width ≥ 1.80 m, in the area; (m non-accessible footpaths/m accessible footpaths) × 100; (2, 3) | 4.0 | 0.9 | 55.6% | |

| U6. Mixed-use planning | 10. Residential-commercial activity | Commercial units in relation to the total number of residential units in the area; (Commercial units/Residential units) × 100; (1) | 4.0 | 0.6 | 77.8% | |

| 11. Balance of mixed-uses | Balance among building uses; Dm = , being n: total number, i: xi value for building use i, and mean value; (1) | 4.1 | 0.7 | 77.8% | ||

| U7. Care facilities | 12. Children care facilities | Number of vacancies for childcare for 2 year olds; number of vacancies in the area; (4) | 4.8 | 0.6 | 88.9% | |

| 13. Elderly care facilities | Number of vacancies in care centers for elderly people, number of vacancies in the area; (4) | 4.8 | 0.6 | 87.5% | ||

| 14. Disabled care facilities | Number of vacancies in care center for disabled-dependent people; number of vacancies in the area; (4) | 4.7 | 0.6 | 88.9% | ||

| U8. Visibility of women | 15. Women street names | Percentage of gender imbalance in city street names; (Number of streets with women’s names/Total streets in the area) × 100; (3, 4) | 3.2 | 1.1 | 33.3% | |

| 16. Inclusive signage | Percentage of inclusive signposting in the area; (Number of inclusive signposting/Total sign postings in the area) × 100; (3, 4) | 3.8 | 1.0 | 55.6% | ||

| B. Buildings | B1. Housing design | 17. Housing variety | Balance among housing typologies; Dm = , being n: total number, i: xi value for housing typology i, and mean value; (2) | 3.6 | 0.9 | 44.4% |

| B2. Energy efficiency | 18. Energy performance | Percentage of buildings with no thermal insulation in their thermal envelope; (Number of buildings built before 1979/Total number of buildings) × 100; (1, 8) | 4.0 | 1.2 | 66.7% | |

| 19. Renewable energy | Percentage of buildings with no renewable energies; (Number of buildings built before 2006/Total number of buildings) × 100; (1, 8) | 3.3 | 1.3 | 44.4% | ||

| B3. Accessibility in housing | 20. Building Accessibility | Percentage of buildings with no elevator; (Number of buildings 4–5 floors built before with no elevator/Total number of buildings) × 100; (1, 3, 8) | 4.9 | 0.3 | 100.0% | |

| 21. Accessibility in housing | Percentage of non-accessible dwellings (1) (Number of buildings built before 1991/Total number of buildings) × 100; (1, 8) | 4.3 | 0.6 | 88.9% | ||

| B4. Quality housing | 22. Buildings conservation | Percentage of buildings in a ruinous and deficient state; (Number of buildings in a ruinous and deficient state/Total number of buildings) × 100; (1) | 3.9 | 0.8 | 77.8% | |

| 23. Buildings constructive quality | Percentage of low-quality buildings; (Number of buildings with quality 7, 8, 9, according to Cadastre scale/Total number of buildings) × 100; (1) | 3.7 | 1.0 | 66.7% | ||

| 24. No acoustic quality | Percentage of buildings with no acoustic quality; (Number of buildings built before 1989/Total number of buildings) × 100; (1, 8) | 3.9 | 0.9 | 66.7% | ||

| 25. Overcrowding | Average number of inhabitants per dwelling; (Number of total inhabitants/Number of total dwellings); (5) | 4.3 | 0.8 | 77.8% | ||

| SD. Socio-demographic | SD1. Demographic data disaggregated by genre | 26. Population over 65 | Percentage of population aged over 65; (Number of inhabitants over 65 years of age/Number of total inhabitants) × 100; (5) | 4.4 | 0.6 | 88.9% |

| 27. Women over 65 | Percentage of women aged over 65; (Number of women over 65 years of age/Number of total inhabitants) × 100; (5) | 4.6 | 0.6 | 88.9% | ||

| 28. Immigrants | Percentage of immigrant population; (Number of immigrant/number of total inhabitants) × 100; (5) | 4.1 | 0.8 | 88.9% | ||

| 29. Women immigrant | Percentage of immigrant women; (Number of immigrant women/Number of total inhabitants) × 100; (5) | 4.2 | 0.6 | 88.9% | ||

| 30. Population under 15 | Percentage of population aged under 15; (Number of inhabitants under 15 years of age/Number of total inhabitants) × 100; (5) | 4.1 | 0.9 | 87.5% | ||

| 31. Women under 15 | Percentage of women aged under 15; (Number of women under 15 years of age/Number of total inhabitants) × 100; (5) | 3.6 | 0.9 | 33.3% | ||

| 32. Aging 65/15 | Percentage of population ratio aged over 65 years and aged under 15 years; (Number of inhabitants aged over 65/Number of inhabitants younger than 15 years) × 100; (5) | 3.3 | 1.2 | 44.4% | ||

| 33. Women Aging 65/15 | Percentage of population ratio aged over 65 and aged under 15; (Number of women aged over 65 years/Number of women younger than 15 years) × 100; (5) | 3.3 | 1.2 | 44.4% | ||

| SD2. Violence and security | 34. Gender violence | Percentage of police interventions due to the fact of gender violence; (6) | 4.6 | 0.6 | 88.9% | |

| 35. Police interventions in housing | Percentage of police interventions due to the fact of housing issues; (Interventions of police for Housing/100 inhabitants); (6) | 4.3 | 1.0 | 77.8% | ||

| 36. Police interventions in streets | Percentage of police interventions due to street issues; (Interventions of police in streets/100 inhabitants); (6) | 4.0 | 1.0 | 66.7% | ||

| 37. Police interventions in traffic | Percentage of police interventions due to the fact of traffic issues; (Interventions of police for traffic/100 inhabitants); (6) | 3.2 | 1.1 | 44.4% | ||

| 38. Police interventions others | Percentage of police interventions due to the fact of other issues; (Interventions of police for other/100 inhabitants); (6) | 2.9 | 1.2 | 33.3% | ||

| 39. Children vulnerability | Percentage of vulnerable children in the area; (Number of vulnerable children in the area/Number of children in the area) × 100; (4) | 4.6 | 0.6 | 88.9% | ||

| 40. Noise complaints | Percentage of police interventions due to the fact of noise issues; (Interventions of police for other/100 inhabitants); (6) | 3.4 | 0.9 | 66.7% | ||

| SD3. Social housing | 41. Municipality’s social Housing | Percentage social housing in the area property of the Municipality; (Number of social housing of the Municipality/Number of total housing units) × 100; (4) | 3.9 | 0.9 | 66.7% | |

| 42. Government’s social Housing | Percentage of social housing properties of the Regional Administration in the area; (Number of social housing of the of the Regional Administration/Number of total housing units) × 100; (7) | 3.9 | 0.9 | 66.7% | ||

| SE. Socio-economic | SE1. Paid or unpaid work | 43. Unemployment rate | Percentage of unemployment in the area; (Number of unemployed people/Total population) × 100; (5) | 4.0 | 0.9 | 77.8% |

| 44. Women unemployment rate | Percentage of unemployment of women in the area; (Number of unemployed women/tTotal population) × 100; (5) | 4.4 | 0.6 | 88.9% | ||

| SE2. Social Subsidies and assistance | 45. Social subsidies | Percentage of social subsidies in the area; (Social subsidies/Number of inhabitants) × 100; (4) | 4.0 | 0.9 | 77.8% | |

| 46. Dependence subsidies | Percentage of dependence subsidies; (Dependence subsidies/Number of inhabitants) × 100; (4) | 4.3 | 0.8 | 77.8% | ||

| 47. Social services assistance | Percentage of social services assistance; (Interventions of police for social service assistance/100 inhabitants); (7) | 4.3 | 1.0 | 77.8% | ||

| SE3. Level of education | 48. Level of education | Percentage of illiterate population who did not complete primary education in the area; (Number of inhabitants with no studies/Number of total inhabitants) × 100; (5) | 4.0 | 0.9 | 77.8% | |

| 49. Level of education in women | Percentage of illiterate women who did not complete primary education in the area; (Number of women with no studies/Number of total inhabitants) × 100; (5) | 4.3 | 0.6 | 88.9% | ||

| 50. Absenteeism from school | Percentage of students registered for absenteeism from school in the area; (Number of cases of absenteeism from school/Number of inhabitants) × 100; (4) | 4.1 | 0.9 | 77.8% | ||

| 51. Children education | Percentage of interventions linked to children education; (Interventions of police for children education/100 inhabitants); (7) | 4.1 | 0.9 | 77.8% | ||

| SE4. Housing market | 52. Tax base | Taxable base of the real estate tax; (€/built m2, in the area); (1) | 3.6 | 1.2 | 66.7% | |

| 53. Cadastral value | Property’s cadastral value; (€/built m2, in the area); (1) | 3.4 | 1.2 | 55.6% | ||

| CC. Cross-curricula | CC1. Women’s participation in decision making | 54. Women participation in urban planning | Presence of women designing the Use Land Plan; (yes/no response); (4) | 4.1 | 0.9 | 77.8% |

| 55. Citizen’s open participatory processes | Existence of participatory processes for citizens in urban planning; (yes/no response); (4) | 4.4 | 0.9 | 88.9% | ||

| 56. Participatory process for vulnerable group of population | Existence of participatory processes for vulnerable populations in urban planning; (yes/no response); (4) | 4.3 | 1.0 | 77.8% | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huedo, P.; Ruá, M.J.; Florez-Perez, L.; Agost-Felip, R. Inclusion of Gender Views for the Evaluation and Mitigation of Urban Vulnerability: A Case Study in Castellón. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810062

Huedo P, Ruá MJ, Florez-Perez L, Agost-Felip R. Inclusion of Gender Views for the Evaluation and Mitigation of Urban Vulnerability: A Case Study in Castellón. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810062

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuedo, Patricia, María José Ruá, Laura Florez-Perez, and Raquel Agost-Felip. 2021. "Inclusion of Gender Views for the Evaluation and Mitigation of Urban Vulnerability: A Case Study in Castellón" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810062

APA StyleHuedo, P., Ruá, M. J., Florez-Perez, L., & Agost-Felip, R. (2021). Inclusion of Gender Views for the Evaluation and Mitigation of Urban Vulnerability: A Case Study in Castellón. Sustainability, 13(18), 10062. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810062