A Backward Walking Training Program to Improve Balance and Mobility in Children with Cerebral Palsy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

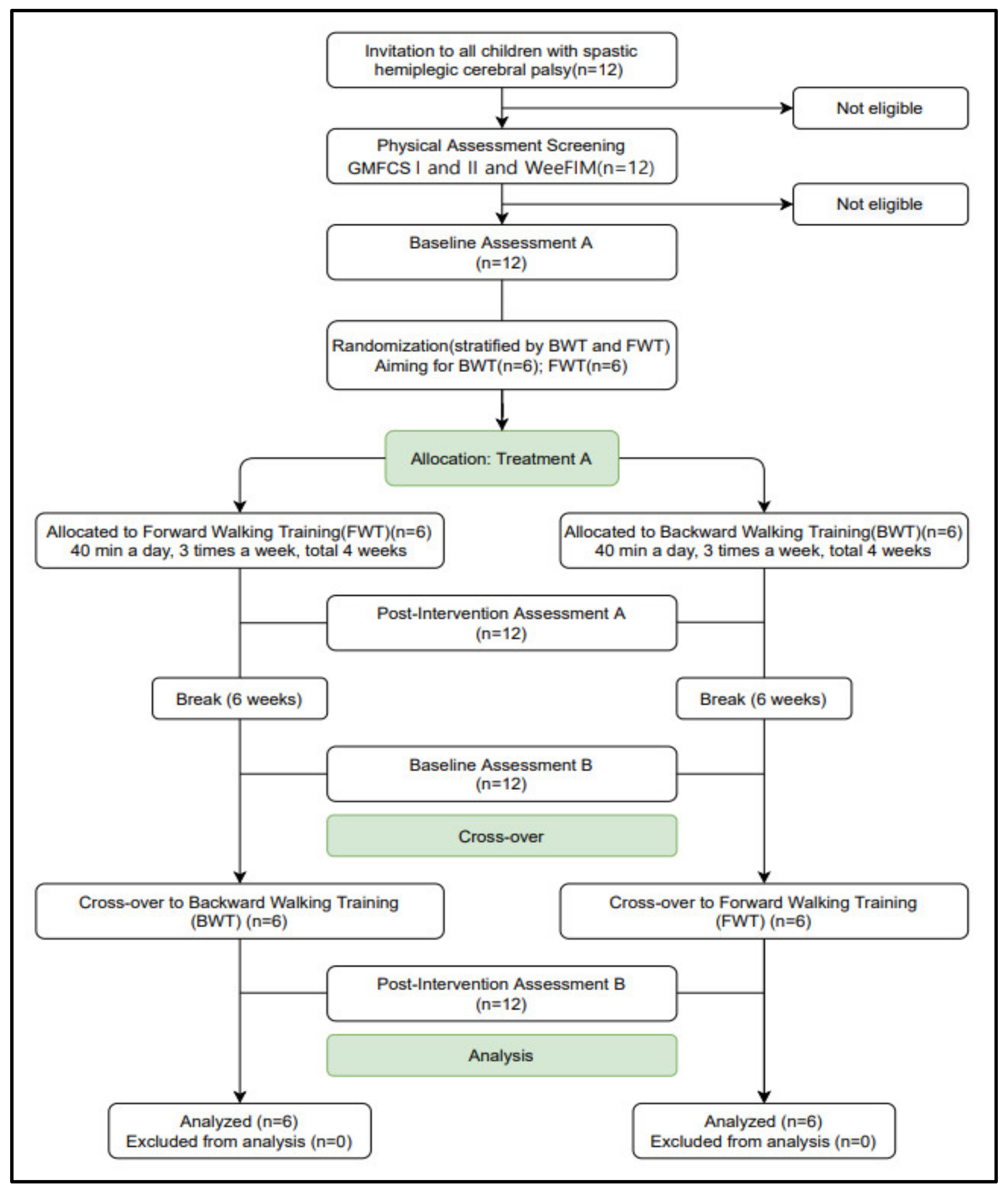

2.2. Procedures and Intervention

2.2.1. Backward Walking Training (BWT)

2.2.2. Forward Walking Training (FWT)

2.2.3. Motor Task

2.3. Measurement

2.3.1. Evaluation for Participant Selection

- (1)

- Cross Motor Functional Classification System (GMFCS)GMFCS is a classification system used for measuring the level of motor disorders in children with cerebral palsy. It is divided into five stages according to movements, such as sitting, crawling, and walking, and the degree of mobility using assistive equipment. From level I, which includes children who can walk without any limitations in movement, to level V, which includes difficulty in movements even with assistive equipment; the higher the step, the lower the functional mobility. The inter- and intra-rater reliabilities are 0.93 and 0.97–0.99, respectively [16].

- (2)

- Pediatric Functional Independent Measure for Children (WeeFIM)WeeFIM is a tool used to assess a child’s functional ability based on their health, development, education, and social conditions. It is divided into areas of motor and cognitive function, classified into six lower measures, and evaluated using 18 items. Among them, communication, and social cognition are evaluated under the cognitive function. Communication is evaluated for possible comprehension and expression and social interactions. Problem-solving skills and memory are evaluated under social cognition. The evaluation method is conducted by direct observation and interviews by the therapist, and each item is scored on a 7-point scale from 1 to 7. The validity and inter-rater reliability are excellent (intraclass correlation coefficients > 0.90) [17,18].

2.3.2. Outcome Measures

- (1)

- Time-Up-and Go TestTUG is a test that can quickly measure dynamic balance and functional mobility over time. It comprises measuring the time taken from getting up from an armchair, walking 3 m, turning around, and walking back 3 m to sit in place. The participant sits with his/her feet flat on the floor so that the hips and knees are in 90° flexion. The therapist measures the time taken to walk 3 m three times and records the average value. It takes about 11 to 12 s for disabled participants, and if it takes more than 20 s, it is determined that help is needed when walking. For the TUG test, the intra- and interrater reliabilities are ICC = 0.99 and ICC = 0.99, respectively. It is a very reliable measurement method [19].

- (2)

- Figure-8 Walk Test (FW8T)FW8T is a test performed to identify the ability to walk in different paths (straight, curved, clockwise, and counterclockwise) and to recognize the task. The FW8T requires the participant to walk a figure-8 around two cones placed 1.5 m apart. The therapist measures the time taken till the return and the step count. The participant is allowed to practice twice along the path of walking before measurement. The FW8T has excellent test–retest (ICCs = 0.84 and 0.82 for time and steps) and inter-rater reliability (ICCs = 0.90 and 0.92 for time and steps) [20].

- (3)

- Pediatric Balance Scale (PBS)The PBS is developed for school-age children with mild and moderate motor disorders. The PBS assesses the balance and functional ADL and is available for use in children from 5 to 15 years old. It consists of 14 items (with five grade levels) including sitting balance, standing balance, sit-to-stand, stand-to-sit, moving from chair to chair, standing on one leg, rotating 360 degrees, reaching to the floor, and reaching forward turning. The performance of each task is evaluated on a scale of 0 to 4 points. The PBS score is calculated as static (6 items), dynamic (8 items), and total components (total score), with a maximum total score of 56. The higher the score, the better the balance [21]. The PBS has shown excellent intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC > 0.9) and inter-rater reliability (ICC > 0.9) [22].

- (4)

- Opto GaitWe used the Opto Gait system (OPTOGait, Microgate, Bolzano, Italy, 2010) consisting of three transmitting and three receiving bars, to collect data on the participants’ walking characteristics. Two bars are placed parallel to each other 1 m apart. Ninety-six LED diodes are positioned on each bar 1 cm apart, 3 mm above the ground. When the participant passes between the transmitting and receiving bars, the system detects the interruption of the optical signal and automatically calculates the spatiotemporal gait parameters based on the presence of a foot in the recording area. The first Opto Gait bar is placed 50 cm from the starting point. The spatiotemporal gait parameters, such as the speed, stride length, and step length of the affected side were analyzed.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freeman, M. Physical Therapy of Cerebral Palsy; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. Suppl. 2007, 109, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Oeffinger, D.J.; Tylkowski, C.M.; Rayens, M.K.; Davis, R.F.; Gorton, G.E., 3rd; D’Astous, J.; Nicholson, D.E.; Damiano, D.L.; Abel, M.F.; Bagley, A.M.; et al. Gross Motor Function Classification System and outcome tools for assessing ambulatory cerebral palsy: A multicenter study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2004, 46, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.L.; Brandt, A.; Samuelsson, K.; Töytäri, O.; Malmivaara, A. Mobility devices to promote activity and participa-tion: A systematic review. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 41, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roos, P.E.; Barton, N.; van Deursen, R.W. Patellofemoral joint compression forces in backward and forward running. J. Biomech. 2012, 45, 1656–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michaelsen, S.M.; Ovando, A.C.; Romaguera, F.; Ada, L. Effect of Backward Walking Treadmill Training on Walking Capacity after Stroke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Stroke 2014, 9, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blundell, S.W.; Shepherd, R.B.; Dean, C.; Adams, R.D.; Cahill, B.M. Functional strength training in cerebral palsy: A pilot study of a group circuit training class for children aged 4–8 years. Clin. Rehabil. 2003, 17, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agmon, M.; Belza, B.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Logsdon, R.; Kelly, V.E. A systematic review of interventions conducted in clinical or community settings to improve dual-task postural control in older adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mulder, T.; Zijlstra, W.; Geurts, A. Assessment of motor recovery and decline. Gait Posture 2002, 16, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haggard, P.; Cockburn, J.; Cock, J.; Fordham, C.; Wade, D. Interference between gait and cognitive tasks in a rehabilitating neurological population. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2000, 69, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, S.J.; Levine, P.; Sisto, S.; Johnston, M.V. A randomized efficacy and feasibility study of imagery in acute stroke. Clin. Rehabil. 2001, 15, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, J.M.; Morris, M. Goal-directed secondary motor tasks: Their effects on gait in subjects with Parkinson disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Basatiny, H.M.Y.; Abdel-aziem, A.A. Effect of backward walking training on postural balance in children with hemipa-retic cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled study. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-R.; Wang, R.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Kao, M.-J. Dual-Task Exercise Improves Walking Ability in Chronic Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.M. Right in the Middle: Selective Trunk Activity in the Treatment of Adult Hemiplegia; Springer Science & Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, E.; Rosenbaum, P. The gross motor function classification system for cerebral palsy: A study of reliability and stability over time. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000, 42, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottenbacher, K.; Taylor, E.T.; Msall, M.E.; Braun, S.; Lane, S.J.; Granger, C.V.; Lyons, N.; Duffy, L.C. The stability and equivalence reliability of the functional independence measure for children (weefim)®. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 38, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperle, P.A.; Ottenbacher, K.J.; Braun, S.L.; Lane, S.J.; Nochajski, S. Equivalency reliability of the Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM) administration methods. Am. J. Occup. 1997, 51, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.J.; Brach, J.S.; Piva, S.R.; VanSwearingen, J.M. Walking skill can be assessed in older adults: Validity of the Fig-ure-of-8 Walk Test. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franjoine, M.R.; Gunther, J.S.; Taylor, M.J. Pediatric Balance Scale: A Modified Version of the Berg Balance Scale for the School-Age Child with Mild to Moderate Motor Impairment. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2003, 15, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gan, S.-M.; Tung, L.-C.; Tang, Y.-H.; Wang, C.-H. Psychometric Properties of Functional Balance Assessment in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Neurorehabilit. Neural. Repair. 2008, 22, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsavelis, D.; Mukherjee, M.; Decker, L.; Stergiou, N. Variability of lower extremity joint kinematics during backward walking in a virtual environment. Nonlinear Dyn. Psychol. Life Sci. 2010, 14, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, D.A.; Pluck, N.; Yang, J.F. Backward Walking: A Simple Reversal of Forward Walking? J. Mot. Behav. 1989, 21, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, H.; DeMark, L.; Spigel, P.M.; Rose, D.K.; Fox, E.J. The effects of backward walking training on balance and mobility in an individual with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury: A case report. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2016, 32, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.K.; DeMark, L.; Fox, E.J.; Clark, D.J.; Wludyka, P. A Backward Walking Training Program to Improve Balance and Mobility in Acute Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2018, 42, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriello, G.; Pathare, N.; Cirone, C.; Pastore, D.; Shears, D.; Sulehri, S. Comparison of forward versus backward walking using body weight supported treadmill training in an individual with a spinal cord injury: A single subject design. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2013, 30, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, I.; Marquer, A.; Eskiizmirliler, S.; Yelnik, A.; Vidal, P.-P. Sensory reweighting in controls and stroke patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVita, P.; Stribling, J. Lower extremity joint kinetics and energetics during backward running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1991, 23, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilam, D.; Adijes, M.; Vilensky, J. Uphill locomotion in mole rats: A possible advantage of backward locomotion. Physiol. Behav. 1995, 58, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilensky, J.; Gankiewicz, E.; Gehlsen, G. A kinematic comparison of backward and forward walking in humans. J. Hum. Mov. Stud. 1987, 13, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, R.; Bianchi, L.; Lacquaniti, F. Motor Patterns for Human Gait: Backward Versus Forward Locomotion. J. Neurophysiol. 1998, 80, 1868–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flynn, T.W.; Connery, S.M.; Smutok, M.A.; Zeballos, R.J.; Weisman, I.M. Comparison of cardiopul-monary responses to forward and backward walking and running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Woollacott, M. Motor Control, 4th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mullie, Y.; Duclos, C. Role of proprioceptive information to control balance during gait in healthy and hemiparetic indi-viduals. Gait Posture 2014, 40, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, S.; Handy, T.C.; Lakhani, B.; Boyd, L.A.; Garland, S.J. Motor and Visuospatial Attention and Motor Planning After Stroke: Considerations for the Rehabilitation of Standing Balance and Gait. Phys. Ther. 2015, 95, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurz, M.J.; Wilson, T.W.; Arpin, D.J. Stride-time variability and sensorimotor cortical activation during walking. NeuroImage 2012, 59, 1602–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M ± SD |

| Sex (male/female) | 5/7 |

| Affected side (Rt./Lt.) | 7/5 |

| GMFCS level (Ⅰ/Ⅱ) | 8/4 |

| Age (years) | 10 ± 2.48 |

| Height (cm) | 125 ± 9.99 |

| Weight (kg) | 27.33 ± 7.35 |

| Forward (n = 12) | Backward (n = 12) | U | p (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | ||||

| TUG | Pre | 13.85 ± 2.00 | 14.90 ± 1.73 | ||

| Post | 13.24 ± 2.24 | 13.33 ± 1.70 | |||

| Post-pre | −0.60 ± 0.59 | −1.57 ± 0.31 | 4.50 | 0.03 | |

| p (1) | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||

| FW8T | Pre | 12.20 ± 3.57 | 12.73 ± 2.74 | ||

| Post | 11.50 ± 3.31 | 11.12 ± 2.45 | |||

| Post-pre | −0.70 ± 0.47 | −1.60 ± 0.48 | 2.00 | 0.01 | |

| p (1) | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||

| PBS | Pre | 42.17 ± 5.03 | 41.33 ± 4.67 | ||

| Post | 43.50 ± 4.88 | 44.50 ± 4.63 | |||

| Post-pre | 1.33 ± 0.51 | 3.17 ± 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| p (1) | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Forward (n = 12) | Backward (n = 12) | U | p (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | ||||

| Velocity (m/s) | Pre | 0.69 ± 0.09 | 0.66 ± 0.11 | ||

| Post | 0.75 ± 0.09 | 0.85 ± 0.14 | |||

| Post-pre | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.11 | 2.00 | 0.00 | |

| p (1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Step (cm) | Pre | 39.46 ± 4.27 | 38.54 ± 4.10 | ||

| Post | 43.29 ± 2.57 | 43.91 ± 3.62 | |||

| Post-pre | 3.83 ± 3.51 | 5.37 ± 3.55 | 50.50 | 0.21 | |

| p (1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Stride (cm) | Pre | 85.38 ± 3.09 | 87.62 ± 4.55 | ||

| Post | 80.50 ± 5.30 | 80.50 ± 3.42 | |||

| Post-pre | 4.87 ± 4.97 | 7.12 ± 4.83 | 50.50 | 0.21 | |

| p (1) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, J.-Y.; Son, S.-M.; Park, S.-H. A Backward Walking Training Program to Improve Balance and Mobility in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091191

Choi J-Y, Son S-M, Park S-H. A Backward Walking Training Program to Improve Balance and Mobility in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Healthcare. 2021; 9(9):1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091191

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Ji-Young, Sung-Min Son, and Se-Hee Park. 2021. "A Backward Walking Training Program to Improve Balance and Mobility in Children with Cerebral Palsy" Healthcare 9, no. 9: 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091191

APA StyleChoi, J.-Y., Son, S.-M., & Park, S.-H. (2021). A Backward Walking Training Program to Improve Balance and Mobility in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Healthcare, 9(9), 1191. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091191