Abstract

Virus infections pose significant global health challenges, especially in view of the fact that the emergence of resistant viral strains and the adverse side effects associated with prolonged use continue to slow down the application of effective antiviral therapies. This makes imperative the need for the development of safe and potent alternatives to conventional antiviral drugs. In the present scenario, nanoscale materials have emerged as novel antiviral agents for the possibilities offered by their unique chemical and physical properties. Silver nanoparticles have mainly been studied for their antimicrobial potential against bacteria, but have also proven to be active against several types of viruses including human imunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, herpes simplex virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and monkey pox virus. The use of metal nanoparticles provides an interesting opportunity for novel antiviral therapies. Since metals may attack a broad range of targets in the virus there is a lower possibility to develop resistance as compared to conventional antivirals. The present review focuses on the development of methods for the production of silver nanoparticles and on their use as antiviral therapeutics against pathogenic viruses.

1. Introduction

Viruses represent one of the leading causes of disease and death worldwide. Thanks to vaccination programmes, some of the numerous diseases that used to kill many and permanently disable others have been eradicated, such as smallpox in 1979 [1] or have greatly reduced the burden of the disease, such as in the case of the paralytic disease poliomyelitis [2]. However, for some of today’s most pressing viral pathogens, there is still no vaccine available. To realize the huge economic impact that several viral diseases cause to the global community, we need only to think to common colds, influenza, various problems due to herpesviruses (from shingles, genital herpes, chickenpox, infectious mononucleosis, up to herpes keratitis, neonatal disseminated infections, or viral encephalitis). Other viruses are also able to cause considerable distress and sometimes persistent infections that may lead to cancer or to acquired immunodeficiencies, such as hepatitis viruses (mainly HBV and HCV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Much effort has been expended in attempts to develop vaccines for these diseases, without appreciable success, at least for some of these viruses, namely, HCV, HIV and some herpesviruses. Presently, the development of new vaccines for such viruses seems likely to continue to be elusive. Together with the risk of emerging or re-emerging viral agents, the field of antiviral compound discovery is very promising.

Emerging and re-emerging viruses are to be considered a continuing threat to human health because of their amazing ability to adapt to their current host, to switch to a new host and to evolve strategies to escape antiviral measures [3].

Viruses can emerge because of changes in the host, the environment, or the vector, and new pathogenic viruses can arise in humans from existing human viruses or from animal viruses. Several viral diseases that emerged in the last few decades have now become entrenched in human populations worldwide. The best known examples are: SARS coronavirus, West Nile virus, monkey pox virus, Hantavirus, Nipah virus, Hendravirus, Chikungunya virus, and last but not least, the threat of pandemic influenza viruses, most recently of avian or swine origin. Unfortunately the methodological advances that led to their detection have not been matched by equal advances in the ability to prevent or control these diseases. There have been improvements in antiviral therapy, but with a wide margin of ineffectiveness, therefore new antiviral agents are urgently needed to continue the battle between invading viruses and host responses. Technological advances have led to the discovery and characterization of molecules required for viral replication and to the development of antiviral agents to inhibit them. Most viruses are, indeed, provided by an extraordinary genetic adaptability, which has enabled them to escape antiviral inhibition and in certain cases to regain advantage over the host by mutagenesis that create new viral strains with acquired resistance to most of the antiviral compounds available [3].

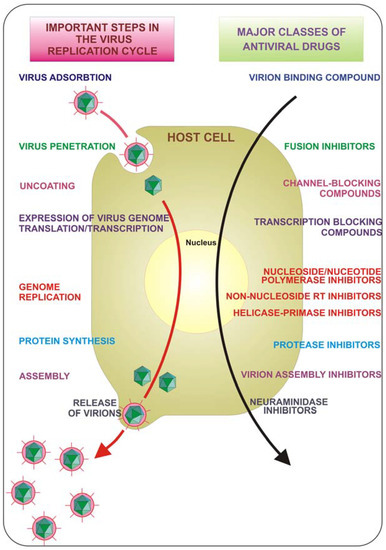

The course of viral infections is governed by complex interactions between the virus and the host cellular system. All viruses depend upon a host cell for their protein synthesis. Thus, all viruses replicate via a broadly similar sequence of events (Figure 1). The virus must first bind to the cell, and then the virus or its genome enters in the cytoplasm. The genome is liberated from the protective capsid and, either in the nucleus or in the cytoplasm, it is transcribed and viral mRNA directs protein synthesis, in a generally well regulated fashion. Finally, the virus undergoes genome replication and together with viral structural proteins assembles new virions which are then released from the cell. Each of the single described phases represents a possible target for inhibition. Drugs that target viral attachment or entrance have proved to be very difficult to be discovered. In fact, to date, only one entry inhibitor has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This is enfuvirtide (T-20), a synthetic peptide that targets the HIV gp41 envelope protein to prevent fusion.

Figure 1.

Key steps in the virus replication cycle that provide antiviral targets.

Targeting the early steps of virus entry is a very attractive strategy for therapeutic intervention since the site of action of the inhibitor is likely to be extracellular and therefore relatively accessible; this could be paired by a concomitant action of the same drug on multiple targets to obtain a more effective therapeutic compound. Moreover one could expect, in the future, antiviral agents with a broad-spectrum of action against viruses of different families, to be used as first aid compounds against unforeseen viral epidemics or pandemics.

Due to the outbreak of the emerging infectious diseases caused by different pathogenic viruses and the development of antiviral resistance to classical antiviral drugs, pharmaceutical companies and numerous researchers are seeking new antiviral agents. In the present scenario, nanoscale materials have emerged as novel “antimicrobial agents” due to their high surface area to volume ratio and their unique chemical and physical properties [4,5].

Nanotechnology is an emerging field of applied science and cutting edge technology that utilizes the physico-chemical properties of nanomaterials as a means to control their size, surface area, and shape in order to generate different nanoscale-sized materials. Among such materials, metal-based ones seem the most interesting and promising, and represent the subject of the present review. Nanotechnology is directly linked with physics, chemistry, biology, material science and medicine. In fact, it finds application in multiple aspects of research and in everyday life such as electronics and new material design. However, its use in medical research is probably one of the fastest growing areas in which the functional mechanisms of nanoparticles and especially metal-based nanoparticles are just beginning to be exploited. Nanotechnologies have been used to develop nanoparticle-based targeted drug carriers [6,7], rapid pathogen detection [8,9], and biomolecular sensing [10], as well as nanoparticle-based cancer therapies [11,12]. The use of nanoparticles can be extended to the development of antivirals that act by interfering with viral infection, particularly during attachment and entry.

Nanoparticles are properly defined as particles with at least one dimension less than 100 nm, and have attracted much attention because of their unique and interesting properties. Their singular physical (e.g., plasmonic resonance, fluorescent enhancement) and chemical (e.g., catalytic activity enhancement) properties derive from the high quantity of surface atoms and the high area/volume relation, in fact, as their diameter decreases, the available surface area of the particle itself increases dramatically and as a consequence there is an increase over the original properties of their bulk materials.

Considering that biological interactions are generally multivalent, the interplay between microbes and host cells often involves multiple copies of receptors and ligands that bind in a coordinated manner, resulting in enhanced specificities, efficiencies, and strengths of such interactions that allow the microbial agent to take possess of the cell under attack. The attachment and entry of viruses into host cells represent a terrific example of such multivalent interactions between viral surface components and cell membrane receptors [13]. Interfering with these recognition events, and thereby blocking viral entry into the cells, is one of the most promising strategies being pursued in the development of new antiviral drugs and preventive topical microbicides [14,15,16]. In recent years, the use of metal nanoparticles, that may or not have been functionalized on their surface for optimising interactions, is seeing increasing success. The idea of exploiting metals against microorganisms can be considered ancient; in fact, the use of silver was a common expedient for cooking procedures and for preserving water from contamination. The importance of silver for its curative properties has been known for centuries, in fact, silver has been the most extensively studied metal for purpose of fighting infections and preventing food spoilage, and notwithstanding the decline of its use as a consequence of the development of antibiotics, prophylaxis against gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum with silver ions was considered the standard of care in many countries until the end of the 20th century [17]. Silver’s mode of action is presumed to be dependent on Ag+ ions, which strongly inhibit bacterial growth through suppression of respiratory enzymes and electron transport components and through interference with DNA functions [18]. Therefore, the antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral properties of silver ions and silver compounds have been extensively studied. Silver has also been found to be non-toxic to humans at very small concentrations. The microorganisms are unlikely to develop resistance against silver as compared to antibiotics as silver attacks a broad range of targets in the microbes. Considering the broad literature that describes silver, as a bulk material, effective against a wide range of pathogens, silver nanoparticles have been analysed and found to be extremely appealing. The silver nanoparticles have also found diverse applications in the form of wound dressings, coatings for medical devices, silver nanoparticles impregnated textile fabrics [19]. The advantage of using silver nanoparticles for impregnation is that there is continuous release of silver ions enhancing its antimicrobial efficacy. The burn wounds treated with silver nanoparticles show better cosmetic appearance and scarless healing [20]. Silver nanoparticles have received considerable attention as antimicrobial agents and have been shown to be effective mainly as antibacterial. Antimicrobial effectiveness was shown for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [21,22].

The antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles was mainly demonstrated by in vitro experiments. Activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [23], Escherichia coli [4,21,24,25], Pseudomonas aeruginosa [4], Vibrio cholera [4] and Bacillus subtilis [25] has been documented. Low concentrations of silver nanoparticles were able to consistently inhibit E. coli [5] while the growth-inhibitory effect on S. aureus was minor. Synergistic antimicrobial activity of silver or zinc nanoparticles with ampicillin, penicillin G, amoxicillin, kanamycin, erythromycin, clindamycin, chloramphenicol and vancomycin against S. aureus, E. coli, Salmonella typhi and Micrococcus luteus was observed [26,27,28].

Also gold nanoparticles have been exploited as antimicrobial agents, mainly as a tool to deliver other antimicrobials or in order to enhance the photodynamic killing of bacteria [29]. Many studies have shown the antimicrobial effects of metal nanoparticles, but the effects of silver nanoparticles against fungal pathogens are mostly unknown; silver nanoparticles, indeed, showed significant antifungal activity against Penicillium citrinum [30], Aspergillus niger [30], Trichophyton Mentagrophytes [31] and Candida albicans [32].

Different types of nanomaterials like copper, zinc, titanium [33], magnesium, gold [34], alginate [35] and silver have come up in recent years and most of them have proven to be effective against diverse microorganisms.

The present review aims at a description of the reported antiviral activities of metal nanoparticles and their production methods, with particular regard to silver nanoparticles.

3. Toxicity

Although the continuous evolutions in the field of metal-based nanoparticles for drug delivery, medical imaging, diagnostics, therapeutics and engineering technology, there is a serious lack of information about the impact of metal nanoparticles on human health and environment, probably due to the intrinsic complex nature of nanoparticles that have led to different attitudes on their safety.

Therefore, an important issue in the use of metal nanoparticles is their potential toxicity. For metal nanoparticles to be effective as antiviral pharmaceuticals, it is imperative to gain a better understanding of their biodistribution/accumulation in living systems.

The principal characteristic of metal nanoparticles is their size, which falls in between individual atoms or molecules and the corresponding bulk materials. Particle size and surface area can modify the physicochemical properties of the metal material, but can also influence the reactivity of nanoparticles with themselves or with the cellular environment, leading to different modes of cellular uptake and further processing, leading to adverse biological effects in living cells that would not otherwise be possible with the same material in larger forms. In fact, as particle size decreases, some metal nanoparticles show increased toxicity, even if the same material is relatively inert in its bulk form (e.g., Ag, Au, and Cu).

Apart from size, the biological consequences of metal nanoparticles also depend on chemical composition, surface structure, solubility, shape, and aggregation. All of these parameters can modify cellular uptake, protein binding, translocation to the target site, and most of the biological interactions with the possibility of causing tissue injury. Therefore, in terms of safety, the effect of silver nanoparticles is a major consideration: even if they inhibit viral infections, it would not be beneficial if there are adverse effects to humans or animals. A commonly used strategy to reduce a possible toxicity is to use various capping agents to prevent the direct contact of the metal with the cells.

Potential routes of human exposure to metal nanoparticles used as therapeutic compounds include the gastrointestinal tract, the skin, the lungs, and systemic administration. Considering the use of metal nanoparticles from the point of view of a potential antiviral therapy, it is straightforward that the safest and easiest results can be obtained with topical use of nanoparticles as microbicide for direct viral particles inactivation and/or inhibition of the early steps of the viral life cycle, attachment and entry. Therefore, the dermal route seems the one of major concern. Dermal exposure to metal nanoparticles often takes place when using sunscreen lotions, for example, TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles. In healthy skin, the epidermis provides excellent protection against particle spread to the dermis. However, in presence of damaged skin micrometer-size particles gain access to the dermis and regional lymph nodes. A further concern should be the potential of nanoparticles translocation to the brain via the olfactory nerve as a consequence of the vicinity of the nasal mucosa to the olfactory bulb. Whether nanoparticles in such tissues have any pathological or clinical significance is uncertain, therefore, more data is needed to properly address the safety concern on the use of metal nanoparticles as pharmaceuticals.

Several studies have demonstrated the cytotoxic effects of metal nanoparticles [90,91,92,93], in fact, silver nanoparticles were found to be highly cytotoxic to mammalian cells based on the assessment of mitochondrial function, membrane leakage of lactate dehydrogenase, and abnormal cell morphologies [90,91,92,93]. At a cellular level, metal nanoparticles interact with biological molecules within mammalian cells and can interfere with the antioxidant defence mechanism leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Such species, in excess, can cause damage to biological components through oxidation of lipids, proteins, and DNA. Oxidative stress may have a role in the induction or the enhancement of inflammation through upregulation of redox sensitive transcription factors (e.g., NF-κB), activator protein-1, and kinases involved in inflammation [94,95,96,97].

The generation of reactive oxygen species by cells exposed to silver nanoparticles [91] has been showed in human lung fibroblast and human glioblastoma cells, and as a consequence DNA damage and cell cycle abnormalities have been observed. Accumulation of silver nanoparticles in various organs (lungs, kidneys, brain, liver, and testes) has been evidenced in animal studies [98]. Most of the in vitro studies show dose dependence, in fact, higher doses of silver induce a strongher cellular toxicity. Nevertheless, should be considered that in vitro concentrations of nanoparticles are often much higher than the ones used in in vivo experiments, therefore such exposures do not represent a replica of the conditions expected for in vivo exposure. A recent study [99] showed that mice exposed to silver nanoparticles showed minimal pulmonary inflammation or cytotoxicity following subacute exposures, but longer term exposures with higher lung burdens of nanosilver are not investigated, therefore eventual cronic effects may be underscored.

This review presents only a brief description of the toxicity derived from the use of metal nanoparticles. A more detailed coverage of the topic is available in recently published reviews [100,101,102,103]. Although significant progress has been made to elucidate the mechanism of silver nanomaterial toxicity, a proved consensus on the immediate impact or long term effect on human health is still missing. Further research is required to provide the necessary warranties to allow a safely exploitation of the interesting in vitro antiviral properties of silver nanoparticles and their transfer to the clinical setting.

4. Metal Nanoparticles Production

Nanoparticles are nanoscale clusters of metallic atoms, engineered for some practical purpose, most typically antimicrobial and sterile applications. Different wet chemical methods have been used for the synthesis of metallic nanoparticles dispersions. The early methods to produce nanoparticles of noble-metals are still used today and continue to be the standard by which other synthesis methods are compared.

The most common methods involve the use of an excess of reducing agents such as sodium citrate [104] or NaBH4 [105]. Ayyanppan et al. [106] obtained Ag, Au, Pd and Cu nanoparticles by reducing metallic salts in dry ethanol. Longenberger et al. [107] produced Au, Ag and Pd metal colloids from air-saturated aqueous solutions of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG). Reduction methods can also be used for the production of Pt, Pd, Cu, Mi etc., although specific protocols depend on the reduction potential of the source ion [108]. Cu and Ni are not very stable as the metal particles are easily oxidized requiring strong capping ligands to prevent the oxidation.

Initially, the reduction of various complexes with metallic ions leads to the formation of atoms, which is followed by agglomeration into oligomeric clusters. Controlled synthesis is usually based on a two-step reduction process: in the first step a strong reducing agent is used to produce small particles; in the second step these small particles are enlarged by further reduction with a weaker reducing agent [104]. Strong reductants lead to small monodisperse particles, while the generation of larger size particles can be difficult to control. Weaker reductants produce slower reduction reactions, but the nanoparticles obtained tend to be more polydisperse in size. Different studies reported the enlargement of particles in the secondary step from about 20–45 nm to 120–170 nm [109].

Another general method for the production of different metal nanoparticles (Au, Ag, Pt, Pd) uses commonly available sugars, e.g., glucose, fructose and sucrose as reducing agents [110]. This approach has several important features: (1) sugars (glucose, fructose, and sucrose) are easily available and are used as reducing agents; (2) upon their exploitation no other stabilizing agent or capping agent is required to stabilize the nanoparticles; (3) sugars are very cheap and biofriendly (4) the nanoparticles can be safely preserved in a essiccator for months and redispersed in aqueous solution whenever required instead of being kept in aqueous solution.

An array of other physical and chemical methods have been used to produce nanomaterials. In order to synthesize noble metal nanoparticles of particular shape and size specific methodologies have been formulated, such as ultraviolet irradiation, aerosol technologies, lithography, laser ablation, ultrasonic fields, and photochemical reduction techniques, although they remain expensive and involve the use of hazardous chemicals. Therefore, there is a growing concern to develop environment-friendly and sustainable methods.

Biosynthesis of gold, silver, gold–silver alloy, selenium, tellurium, platinum, palladium, silica, titania, zirconia, quantum dots, magnetite and uraninite nanoparticles by bacteria, actinomycetes, fungi, yeasts and viruses have been reported. However, despite the stability, biological nanoparticles are not monodispersed and the rate of synthesis is slow. To overcome these problems, several factors such as microbial cultivation methods and extraction techniques have to be optimized and factors such as shape, size and nature can be controlled through just modifying pH, temperature and nutrient media composition. Owing to the rich biodiversity of microbes, their potential as biological materials for nanoparticle synthesis is yet to be fully explored. The production of metal nanoparticles involves three main steps, including (1) selection of solvent medium; (2) selection of environmentally benign reducing agent; (3) selection of nontoxic substances for the nanoparticles stability [111].

Biomineralization is also an attractive technique, being the best nature friendly method of nanoparticle synthesis. In one of the biomimetic approaches towards generation of nanocrystals of silver, reduction of silver ions has been carried out using bacteria and unicellular organisms. The reduction is mediated by means of an enzyme and the presence of the enzyme in the organism has been found to be responsible of the synthesis [112,113].

Therefore in search of a methodology that could provide safer and easier synthesis of metal nanoparticles, it seems that the biogenic synthesis using the filtrated supernatant of different bacterial and fungal cultures is having a considerable impact, where the reduction of metal ions occurs through the release of reductase enzymes into the solution [28,114,115,116]. For an extensive coverage of the biological synthesis of metal nanoparticles by microbes, refer to the recent review by Narayanan and Sakthivel [117].

5. Conclusions

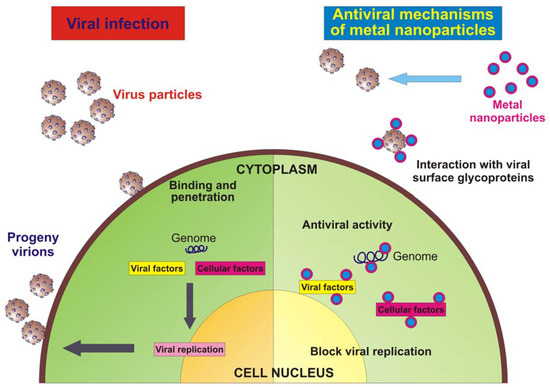

In the crusade toward the development of drugs for the therapy of viral diseases, the emergence of resistant viral strains and adverse side effects associated with a prolonged use represent huge obstacles that are difficult to circumvent. Therefore, multidisciplinary research efforts, integrated with classical epidemiology and clinical approaches, are crucial for the development of improved antivirals through alternative strategies. Nanotechnology has emerged giving the opportunity to re-explore biological properties of known antimicrobial compounds, such as metals, by the manipulation of their sizes. Metal nanoparticles, especially the ones produced with silver or gold, have proven to exhibit virucidal activity against a broad-spectrum of viruses, and surely to reduce viral infectivity of cultured cells. In most cases, a direct interaction between the nanoparticle and the virus surface proteins could be demonstrated or hypothesized. The intriguing problem to be solved is to understand the exact site of interaction and how to modify the nanoparticle surface characteristics for a broader and more effective use. Besides the direct interaction with viral surface glycoproteins, metal nanoparticles may gain access into the cell and exert their antiviral activity through interactions with the viral genome (DNA or RNA). Furthermore, the intracellular compartment of an infected cell is overcrowded by virally encoded and host cellular factors that are needed to allow viral replication and a proper production of progeny virions. The interaction of metal nanoparticles with these factors, which are the key to an efficient viral replication, may also represent a further mechanism of action (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic model of a virus infecting an eukaryotic cell and antiviral mechanism of metal nanoparticles.

Most of the published literature describes the antiviral activity of silver or gold nanoparticles against enveloped viruses, with both a DNA or an RNA genome. Considering that one of the main arguments toward the efficacy of the analysed nanoparticles is the fact that they in virtue of their shape and size, can interact with virus particles with a well-defined spatial arrangement, the possibility of metal nanoparticles being active against naked viruses seems appealing. Moreover, it has been already proven that both silver and gold nanoparticles may be used as a core material. However, no reports are yet available for the use of other metals, but the future holds many surprises, especially considering that the capping molecules that could be investigated are virtually unlimited.

Nonetheless, for metal nanoparticles to be used in therapeutic or prophylactic treatment regimens, it is critical to understand the in vivo toxicity and potential for long-term sequelae associated with the exposure to these compounds. Additional research is needed to determine how to safely design, use, and dispose products containing metal nanomaterials without creating new risk to humans or the environment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Henderson, D.A. Principles and lessons from the smallpox eradication programme. Bull. World Health Organ. 1987, 65, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hull, H.F.; Ward, N.A.; Hull, B.P.; Milstien, J.B.; de Quadros, C. Paralytic poliomyelitis: Seasoned strategies, disappearing disease. Lancet 1994, 343, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, D. Mechanisms of viral emergence. Vet. Res. 2010, 41, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Morones, J.R.; Elechiguerra, J.L.; Camacho, A.; Holt, K.; Kouri, J.B.; Ramírez, J.T.; Yacaman, M.J. The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 2005, 16, 2346–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Kuk, E.; Yu, K.N.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Park, Y.K.; Park, Y.H.; Hwang, C.Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, Y.S.; Jeong, D.H.; Cho, M.H. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2007, 3, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falanga, A.; Vitiello, M.T.; Cantisani, M.; Tarallo, R.; Guarnieri, D.; Mignogna, E.; Netti, P.; Pedone, C.; Galdiero, M.; Galdiero, S. A peptide derived from herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H: Membrane translocation and applications to the delivery of quantum dots. Nanomedicine 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallaj-Nezhadi, S.; Lotfipour, F.; Dass, C.R. Delivery of nanoparticulate drug delivery systems via the intravenous route for cancer gene therapy. Pharmazie 2010, 65, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Gontard, L.C.; Thuy Tram le, L.; Wolff, A.; Bang, D.D. Dual enlargement of gold nanoparticles: From mechanism to scanometric detection of pathogenic bacteria. Small 2011, 7, 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daaboul, G.G.; Yurt, A.; Zhang, X.; Hwang, G.M.; Goldberg, B.B.; Ünlü, M.S. High-throughput detection and sizing of individual low-index nanoparticles and viruses for pathogen identification. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4727–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, O.R.; Creran, B.; Rotello, V.M. Array-based sensing with nanoparticles: Chemical noses’ for sensing biomolecules and cell surfaces. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, L.C.; Bickford, L.R.; Lewinski, N.A.; Coughlin, A.J.; Hu, Y.; Day, E.S.; West, J.L.; Drezek, R.A. A new era for cancer treatment: Gold-nanoparticle-mediated thermal therapies. Small 2011, 7, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portney, N.G.; Ozkan, M. Nano-oncology: Drug delivery, imaging, and sensing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 384, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helenius, A. Fields “Virology” Fifth Edition: Virus Entry and Uncoating; LWW: London, UK, 2007; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov, D.S. Virus entry: Molecular mechanisms and biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. 2004, 2, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitiello, M.; Galdiero, M.; Galdiero, M. Inhibition of viral-induced membrane fusion by peptides. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009, 16, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melby, T.; Westby, M. Inhibitors of viral entry. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2009, 189, 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyme, U.B. Clinical significance of Credé’s prophylaxis in germany at present. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993, 1, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Leung, P.; Yao, L.; Song, Q.W.; Newton, E. Antimicrobial effect of surgical masks coated with nanoparticles. J. Hosp. Infect. 2006, 62, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Afrin, T.; Xu, W.; Sun, L.; Wang, X. Application of anisotropic silver nanoparticles: Multifunctionalization of wool fabric. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 356, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaloupka, K.; Malam, Y.; Seifalian, AM. Nanosilver as a new generation of nanoproduct in biomedical applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondi, I.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: A case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 275, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.; Sun, W.; Qian, W.; Ye, Y.; Ma, X. The synthesis of chitosan-based silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panacek, A.; Kvítek, L.; Prucek, R.; Kolar, M.; Vecerova, R.; Pizúrova, N.; Sharma, V.K.; Nevecna, T.; Zboril, R. Silver colloid nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and their antibacterial activity. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 16248–16253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.; Tak, Y.K.; Song, J.M. Does the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles depend on the shape of the nanoparticle? A study of the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, K.Y.; Hoon Byeon, J.; Park, J.H.; Hwang, J. Susceptibility constants of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis to silver and copper nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 373, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahverdi, A.R.; Fakhimi, A.; Shahverdi, H.R.; Minaian, S. Synthesis and effect of silver nanoparticles on the antibacterial activity of different antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Nanomedicine 2007, 3, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banoee, M.; Seif, S.; Nazari, Z.E.; Jafari-Fesharaki, P.; Shahverdi, H.R.; Moballegh, A.; Moghaddam, K.M.; Shahverdi, A.R. ZnO nanoparticles enhanced antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2010, 93, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayaz, A.M.; Balaji, K.; Girilal, M.; Yadav, R.; Kalaichelvan, P.T.; Venketesan, R. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their synergistic effect with antibiotics: A study against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2010, 6, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pissuwan, D.; Valenzuela, S.M.; Miller, C.M.; Killingsworth, M.C.; Cortie, M.B. Destruction and control of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites using gold nanosphere/antibody conjugates. Small 2009, 5, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, H.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, D. Facile preparation and characterization of highly antimicrobial colloid Ag or Au nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 325, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.J.; Sung, W.S.; Moon, S.K.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, D.G. Antifungal effect of silver nanoparticles on dermatophytes. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 18, 1482–1484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.J.; Sung, W.S.; Suh, B.K.; Moon, S.K.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, J.G. Antifungal activity and mode of action of silver nano-particles on Candida albicans. Biometals 2009, 22, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schabes-Retchkiman, P.S.; Canizal, G.; Herrera-Becerra, R.; Zorrilla, C.; Liu, H.B.; Ascencio, J.A. Biosynthesis and characterization of Ti/Ni bimetallic nanoparticles. Opt. Mater. 2006, 29, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, W.; Ma, W.; Jiang, X. Small molecule-capped gold nanoparticles as potent antibacterial agents that target Gram-negative bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12349–12356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, Z.; Sharma, S.; Khuller, G.K. Inhalable alginate nanoparticles as antitubercular drug carriers against experimental tuberculosis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 26, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rai, M.; Yadav, A.; Gade, A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elechiguerra, J.L.; Burt, J.L.; Morones, J.R.; Camacho-Bragado, A.; Gao, X.; Lara, H.H.; Yacaman, M.J. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with HIV-1. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2005, 29, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.W.; Chen, R.; Chung, N.P.; Ho, C.M.; Lin, C.L.; Che, C.M. Silver nanoparticles fabricated in Hepes buffer exhibit cytoprotective activities toward HIV-1 infected cells. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2005, 40, 5059–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, H.H.; Ayala-Nuñez, N.V.; Ixtepan-Turrent, L.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C. Mode of antiviral action of silver nanoparticles against HIV-1. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, H.H.; Ixtepan-Turrent, L.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C. PVP-coated silver nanoparticles block the transmission of cell-free and cell-associated HIV-1 in human cervical culture. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Sun, R.W.; Chen, R.; Hui, C.K.; Ho, C.M.; Luk, J.M.; Lau, G.K.; Che, C.M. Silver nanoparticles inhibit hepatitis B virus replication. Antivir. Ther. 2008, 13, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Singh, A.K.; Vig, K.; Pillai, S.; Shreekumar, R.; Singh, S.R. Silver nanoparticles inhibit replication of respiratory sincitial virus. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2008, 4, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Baram-Pinto, D.; Shukla, S.; Perkas, N.; Gedanken, A.; Sarid, R. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection by silver nanoparticles capped with mercaptoethane sulfonate. Bioconjug. Chem. 2009, 20, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baram-Pinto, D.; Shukla, S.; Gedanken, A.; Sarid, R. Inhibition of HSV-1 attachment, entry, and cell-to-cell spread by functionalized multivalent gold nanoparticles. Small 2010, 6, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.V.; Parkinson, C.V.; Choi, Y.W.; Speshock, J.L.; Hussain, S.M. A preliminary assessment of silver nanoparticles inhibition of monkeypox virus plaque formation. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, I.; Sieben, C.; Ludwig, K.; Roskamp, M.; Böttcher, C.; Schlecht, S.; Herrmann, A.; Haag, R. Inhibition of influenza virus infection by multivalent sialic-acid-functionalized gold nanoparticles. Small 2010, 6, 2900–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speshock, J.L.; Murdock, R.C.; Braydich-Stolle, L.K.; Schrand, A.M.; Hussain, S.M. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with Tacaribe virus. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukasem, C.; Churdboonchart, V.; Sukeepaisarncharoen, W.; Piroj, W.; Inwisai, T.; Tiensuwan, M.; Chantratita, W. Genotypic resistance profiles in antiretroviral-naive HIV-1 infections before and after initiation of first-line HAART: Impact of polymorphism on resistance to therapy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 31, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doms, R.W.; Moore, J.P. HIV-1 membrane fusion: Targets of opportunity. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, K.H.; Taylor, K.A. AIDS virus envelope spike structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007, 17, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, P. Retroviridae: The retroviruses and their replication. In Virology, 5th Ed. ed; LWW: London, UK, 2007; pp. 2000–2069. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, F.; Guery, C.; Guyomard, D.; Urbina, R.H.; Tekaia-Elhsissen, K.; Tarascon, J.M. Electrochemical reduction of noble metal compounds in ethylene glycol. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 1999, 1, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.B.; Patterson, B.K.; Naus, G.J.; Landers, D.V.; Gupta, P. Development of an in vitro organ culture model to study transmission of HIV-1 in the female genital tract. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zussman, A.; Lara, L.; Lara, H.H.; Bentwich, Z.; Borkow, G. Blocking of cell-free and cell-associated HIV-1 transmission through human cervix organ culture with UC781. AIDS 2003, 17, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellet, P.E.; Roizman, B. The Family HERPESVIRIDAE: A brief introduction. In Virology, 5th Ed. ed; LWW: London, UK, 2007; pp. 2479–2499. [Google Scholar]

- Roizman, B.; Knipe, D.M.; Whitley, R.J. Fields herpes simplex viruses. In Virology, 5th Ed. ed; LWW: London, UK, 2007; pp. 2502–2601. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, S.; Jackson, J.; Jardetzky, T.S.; Longnecker, R. Fusing structure and function: A structural view of the herpesvirus entry machinery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spear, P.G. Herpes simplex virus: Receptors and ligands for cell entry. Cell. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, D.; Spear, P.G. Herpesviruses and heparin sulfate: An intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 108, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.; Bruun, B.; Minson, T.; Browne, H. Glycoproteins gB, gD, and gHgL of herpes simplex virus type 1 are necessary and sufficient to mediate membrane fusion in a Cos cell transfection system. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 873–875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heldwein, E.E.; Krummenacher, C. Entry of herpesviruses into mammalian cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 1653–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldwein, E.E.; Lou, H.; Bender, F.C.; Cohen, G.H.; Eisenberg, R.J.; Harrison, S.C. Crystal structure of glycoprotein B from herpes simplex virus 1. Science 2006, 313, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannah, B.P.; Heldwein, E.E.; Bender, F.C.; Cohen, G.H.; Eisenberg, R.J. Mutational evidence of internal fusion loops in herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4858–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stampfer, S.D.; Lou, H.; Cohen, G.H.; Eisenberg, R.J.; Heldwein, E.E. Structural basis of local, pH-dependent conformational changes in glycoprotein B from herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 12924–12933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdiero, S.; Falanga, A.; Vitiello, M.; Browne, H.; Pedone, C.; Galdiero, M. Fusogenic domains in herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 28632–28643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdiero, S.; Vitiello, M.; D’Isanto, M.; Falanga, A.; Collins, C.; Raieta, K.; Pedone, C.; Browne, H.; Galdiero, M. Analysis of synthetic peptides from heptad-repeat domains of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoproteins H and B. J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdiero, S.; Falanga, A.; Vitiello, M.; D’Isanto, M.; Collins, C.; Orrei, V.; Browne, H.; Pedone, C.; Galdiero, M. Evidence for a role of the membrane-proximal region of herpes simplex virus Type 1 glycoprotein H in membrane fusion and virus inhibition. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdiero, S.; Falanga, A.; Vitiello, M.; Raiola, L.; Fattorusso, R.; Browne, H.; Pedone, C.; Isernia, C.; Galdiero, M. Analysis of a membrane interacting region of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 29993–30009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdiero, S.; Falanga, A.; Vitiello, M.; Raiola, L.; Russo, L.; Pedone, C.; Isernia, C.; Galdiero, M. The presence of a single N-terminal histidine residue enhances the fusogenic properties of a Membranotropic peptide derived from herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 17123–17136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.C.; Baines, J.D. Herpesviruses remodel host membranes for virus egress. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, P.L.; Crowe, J.E., Jr. Respiratory syncytial virus and metapneumovirus. In Virology, 5th ed.; LWW: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1601–1646. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger, C.; Zoulin, F.; Mason, W.S. Hepadnaviruses. In Virology, 5th ed.; LWW: London, UK, 2007; pp. 2977–3029. [Google Scholar]

- Palese, P.; Shaw, M.L. Orthomyxoviridae: The viruses and their replication. In Virology, 5th ed.; LWW: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1647–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.; Nuara, A.; Buller, R.M.; Schultz, D.A. Human monkeypox: An emerging zoonotic disease. Future Microbiol. 2007, 2, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchimier, M.J.; de la Torre, J.-C.; Peters, C.J. The viruses and their replication. In Virology, 5th Ed. ed; LWW: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1791–1827. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C.R.; Lewicki, H.; Allison, L.; Salter, M.; Buchmeier, M.J. Properties and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to tacaribe virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1985, 66, 2344–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iapalucci, S.; López, N.; Franze-Fernández, M.T. The 3’ end termini of the Tacaribe arenavirus subgenomic RNAs. Virology 1991, 182, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwonand, S.; Ostler, E. Antimicrobial effect of silver-impregnated cellulose: Potential for antimicrobial therapy. J. Biol. Eng. 2009, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaszadegan, M.; Lechevallier, M.; Gerba, C. Occurrence of viruses in US groundwaters. J. AWWA 2003, 95, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, I.A.; Jurzik, L.; Wilhelm, M.; Uberla, K. Detection and quantification of human bocavirus in river water. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 2634–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.; Kumar, L.; Jenkins, T.M.; Xagoraraki, I.; Phanikumar, M.S.; Rose, J.B. Evaluation of public health risks at recreational beaches in Lake Michigan via detection of enteric viruses and a human-specific bacteriological marker. Water Res. 2009, 43, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Lin, W.Y.; Zainal, Z.; Williams, N.E.; Zhu, K.; Kruzic, A.P.; Smith, R.L.; Rajeshwar, K. Bactericidal activity of TiO2 photocatalyst in aqueous media: Toward a solar-assisted water disinfection system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1994, 28, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Sunada, K.; Iyoda, T.; Hashimoto, K.; Fujishima, A. Photocatalitic bactericidal effect of TiO2 thin films: Dynamic view of the active oxygen species responsible for the effect. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1997, 106, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Chung, H.; Choi, W.; Yoon, J. Different inactivation behaviors of MS-2 phage and Escherichia coli in TiO2 photocatalytic disinfection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benabbou, A.K.; Derriche, Z.; Felix, C.; Lejeune, P.; Guillard, C. Photocatalytic inactivation of Escherischia coli. Effect of concentration of TiO2 and microorganism, nature, and intensity of UV irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2007, 76, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.R.; Martin, S.T.; Choi, W.; Bahnemann, D.W. Environmental applications of semiconductor photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belháčová, L.; Josef, K.; Josef, G.; Jikovsky, J. Inactivation of microorganisms in a flow-through photoreactor with an immobilized TiO2 layer. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1999, 74, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, Y.; Taya, M. Kinetic evaluation of biocidal activity of titanium dioxide against phage MS2 considering interaction between the phage and photocatalyst particles. Biochem. Eng. J. 2002, 12, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liga, M.V.; Bryant, E.L.; Colvin, V.L.; Li, Q. Virus inactivation by silver doped titanium dioxide nanoparticles for drinking water treatment. Water Res. 2011, 45, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braydich-Stolle, L.; Hussain, S.; Schlager, J.J.; Hofmann, M.C. In vitro cytotoxicity of nanoparticles in mammalian germline stem cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2005, 88, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AshaRani, P.V.; Low Kah Mun, G.; Hande, M.P.; Valiyaveettil, S. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawata, K.; Osawa, M.; Okabe, S. In vitro toxicity of silver nanoparticles at noncytotoxic doses to HepG2 human hepatoma cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 6046–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.M.; Hess, K.L.; Gearhart, J.M.; Geiss, K.T.; Schlager, J.J. In vitro toxicity of nanoparticles in BRL 3A rat liver cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2005, 19, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, I. Regulation of nuclear factor-κB, activator protein-1, and glutathione levels by tumor necrosis factor-α and dexamethasone in alveolar epithelial cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000, 60, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Biswas, S.K.; Jimenez, L.A.; Torres, M.; Forman, H.J. Glutathione, stress responses, and redox signaling in lung inflammation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005, 7, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanone, S.; Boczkowski, J. Biomedical applications and potential health risks of nanomaterials: Molecular mechanisms. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006, 6, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aillon, K.L.; Xie, Y.; El-Gendy, N.; Berkland, C.J.; Forrest, M.L. Effects of nanomaterial physicochemical properties on in vivo toxicity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, H.S.; Rha, D.S.; Kim, J.M.; Park, J.D.; Choi, B.S.; Lim, R.; Chang, H.K.; Chung, Y.H.; et al. Twenty-eight-day oral toxicity, genotoxicity, and gender-related tissue distribution of silver nanoparticles in Sprague-Dawley rats. Inhal. Toxicol. 2008, 20, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stebounova, L.V.; Adamcakova-Dodd, A.; Kim, J.S.; Park, H.; O’Shaughnessy, P.T.; Grassian, V.H.; Thorne, P.S. Nanosilver induces minimal lung toxicity or inflammation in a subacute murine inhalation model. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2011, 8, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panyala, N.R.; Peña-Méndez, E.M.; Havel, J. Silver or silver nanoparticles: A hazardous threat to the environment and human health? J. Appl. Biomed. 2008, 6, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Schluesener, H. Nanosilver: A nanoproduct in medical application. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 176, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marambio-Jones, C.; Hoek, E.M.V. A review of the antibacterial effects of silver nanomaterials and potential implications for human health and the environment. J. Nanopart. Res. 2010, 12, 1531–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrand, A.M.; Rahman, M.F.; Hussain, S.M.; Schlager, J.J.; Smith, D.A.; Syed, A.F. Metal-based nanoparticles and their toxicity assessment. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 2, 544–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.C.; Meisel, D. Adsorption and surface-enhanced Raman of dyes on silver and gold sols. J. Phys. Chem. 1982, 86, 3391–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, J.A.; Blatchford, C.G.; Albrecht, M.G. Plasma resonance enhancement of Raman scattering by pyridine adsorbed on silver or gold sol particles of size comparable to the excitation wavelength. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 Mol. Chem. Phys. 1979, 75, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyappan, S.; Srinivasa, G.R.; Subbanna, G.N.; Rao, C.N.R. Nanoparticles of Ag, Au, Pd, and Cu produced by alcohol reduction of the salts. J. Mater. Res. 1997, 12, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longenberger, L.; Mills, G. Formation of metal particles in aqueous solutions by reactions of metal complexes with polymers. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.W.J.; Ye, H.; Henriquez, R.R.; Crooks, R.M. Synthesis, characterization, and stability of dendrimer-encapsulated palladium nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 3873–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirtcliffe, N.; Nickel, U.; Schneider, S. Reproducible preparation of silver sols with small particle size using borohydride reduction: For use as nuclei for preparation of larger particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999, 211, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panigrahi, S.; Kundu, S.; Kumar Ghosh, S.; Nath, S.; Pal, T. General method of synthesis for metal nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 2004, 6, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, P.; Fu, J.; Wallen, S.L. Completely “green” synthesis and stabilization of metal nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 13940–13941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalimuthu, K.; Suresh Babu, R.; Venkataraman, D.; Bilal, M.; Gurunathan, S. Biosynthesis of silver nanocrystals by Bacillus licheniformis. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2008, 65, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalishwaralal, K.; Deepak, V.; Ram Kumar Pandian, S.; Kottaisamy, M.; BarathmaniKanth, S.; Kartikeyan, B.; Gurunathan, S. Biosynthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles using Brevibacterium casei. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 77, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajbhiye, M.; Kesharwani, J.; Ingle, A.; Gade, A.; Rai, M. Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against pathogenic fungi in combination with fluconazole. Nanomedicine 2009, 5, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, A.; Saravanan, M. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Staphylococcus aureus and its antimicrobial activity against MRSA and MRSE. Nanomedicine 2009, 5, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanan, M.; Nanda, A. Extracellular synthesis of silver bionanoparticles from Aspergillus clavatus and its antimicrobial activity against MRSA and MRSE. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 77, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, K.B.; Sakthivel, N. Biological synthesis of metal nanoparticles by microbes. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 156, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).