Abstract

The elemene-type terpenoids, which possess various biological activities, contain a syn- or anti-1,2-dialkenylcyclohexane framework. An efficient synthetic route to the syn- and anti-1,2-dialkenylcyclohexane core and its application in the synthesis of (±)-geijerone and its diastereomer is reported. Construction of the syn- and anti-1,2-dialkenyl moiety was achieved via Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of the (E)-allylic ester, and the cyclohexanone moiety was derived from the iodoaldehyde via intramolecular Barbier reaction. The synthetic strategy allows rapid access to various epimers and analogues of elemene-type products.

1. Introduction

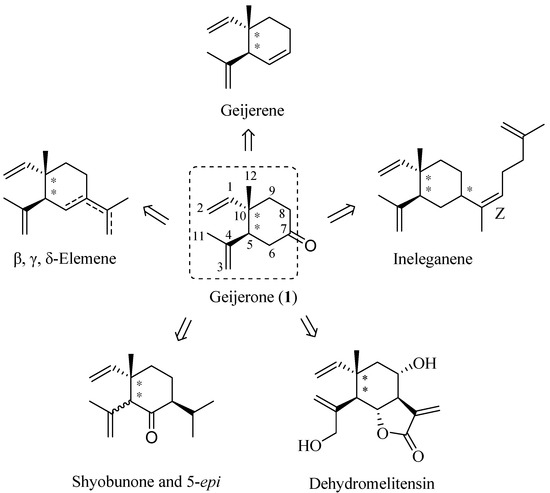

Natural products continue to attract intense attention due to their various bioactivities and they have played a vital role in the field of drug discovery in recent decades. Most of the drugs in the clinical market today are inspired by or derived from natural sources [1]. β-Elemene, γ-elemene, δ-elemene, geijerene, ineleganene, shyobunone and dehydromelitensin are natural terpenoids with a syn- or anti-1,2-dialkenylcyclohexane skeleton (Figure 1), and exist in various essential oils [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. These compounds or their racemic mixtures have been shown to inhibit tumor cell growth in vitro and in vivo [10,11,12,13,14,15]. The mixture of β-elemene, γ-elemene and δ-elemene has been put into clinical trials in cancer patients in China [16,17].

A lot of efforts have been made towards the synthesis of these compounds due to their specific structures and important biological activities. For instance, Wu’s group reported the synthesis of elemene derivatives starting from carvone, employing a double Michael reaction as the key step [18,19]. In addition, other colleagues have reported their synthetic strategies for the synthesis of β-elemene, including Cope rearrangement, Ireland-Claisen rearrangement, doubly diastereo-differentiating folding and allylic strain-controlled intramolecular ester enolate alkylation [20,21,22,23,24].

Structurally, (±)-geijerone (1, Figure 1) contains a highly functionalized anti-1,2-dialkenyl-cyclohexane moiety and the 7-carbonyl group of (±)-geijerone (1) is beneficial for derivatization reactions. Therefore, (±)-geijerone (1) could be considered as a common precursor in the synthesis of elemene-type terpenoids. Kim utilized an intramolecular ester enolate alkylation to construct (±)-geijerone (1) and synthesized ã-elemene by starting from a rare lactol [25]. Another synthesis of (±)-geijerone (1) was reported by Yoshikoshi, using the Wieland-Miescher ketone as the starting material [26]. As a part of our synthetic studies on direct construction of the syn- and anti-1,2-dialkenylcyclohexane skeleton and bioactive elemene-type terpenoids we describe herein a novel and alternative synthesis of a mixture of two diastereomers of (±)-geijerone (1) by starting from the chainlike and commercially available geraniol (2).

Figure 1.

Structures of elemene-type terpenoids and (±)-geijerone (1).

Figure 1.

Structures of elemene-type terpenoids and (±)-geijerone (1).

2. Results and Discussion

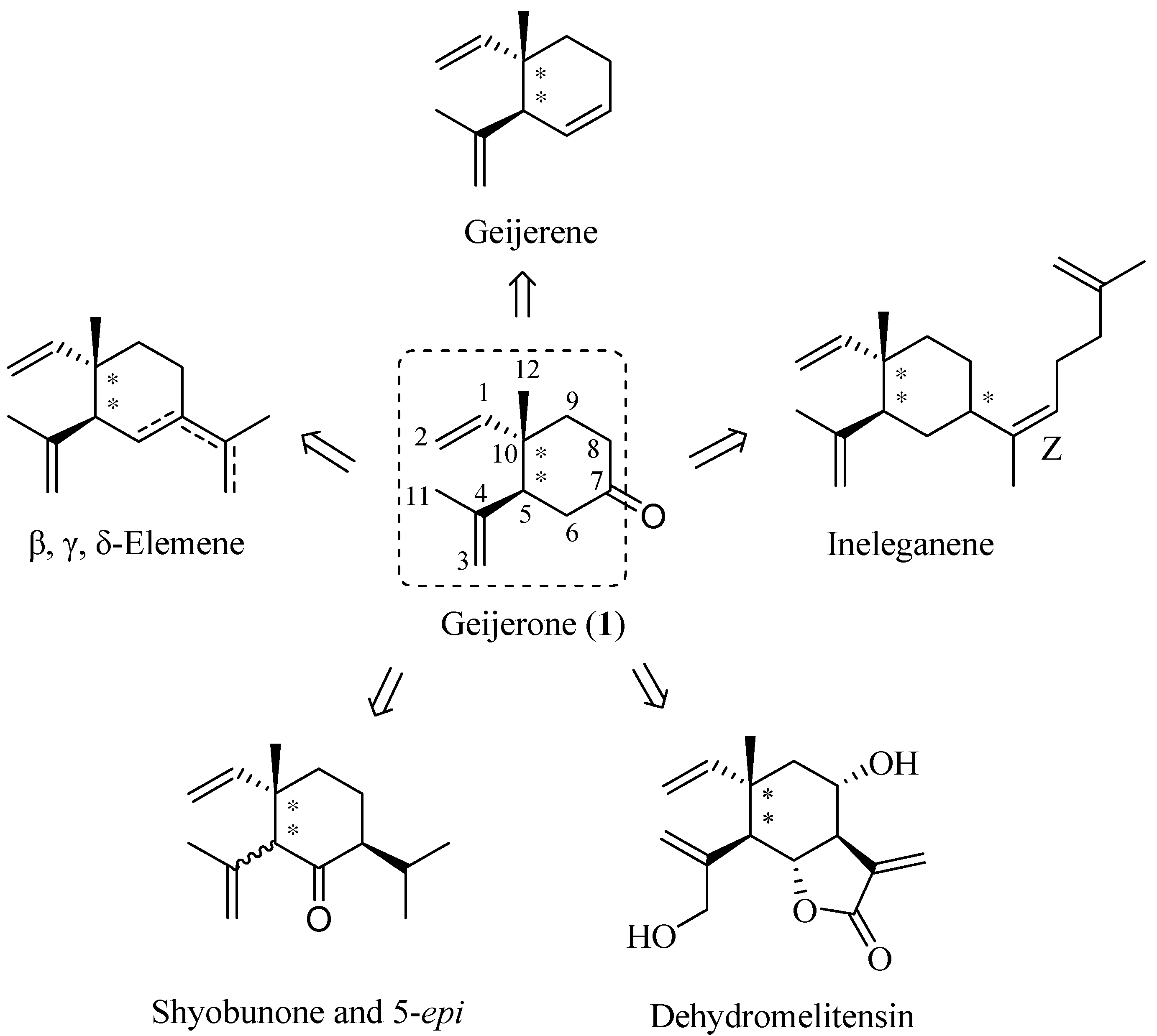

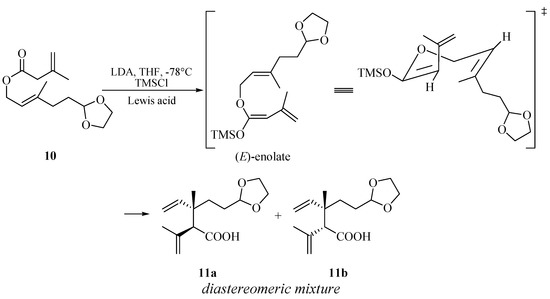

The retrosynthetic analysis is outlined in Scheme 1. (±)-Geijerone could be synthesized from 14a via intramolecular Barbier reaction and subsequent oxidation. The conversion of 11a to 14a could be achieved by conventional methods. The anti-1,2-dialkenyl carboxylic acid 11a could be constructed from (E)-allylic ester 10 using an Ireland-Claisen rearrangement as the key step. The ester 10 could be derived from geraniol (2) and 3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol (8).

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of (±)-geijerone (1).

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of (±)-geijerone (1).

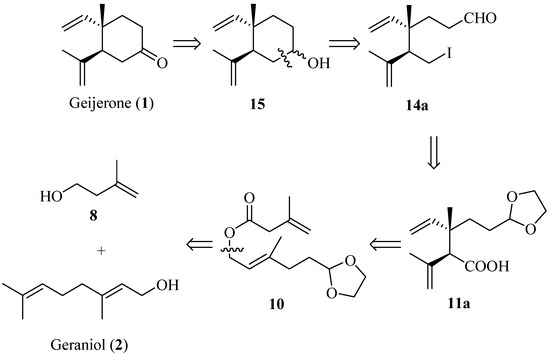

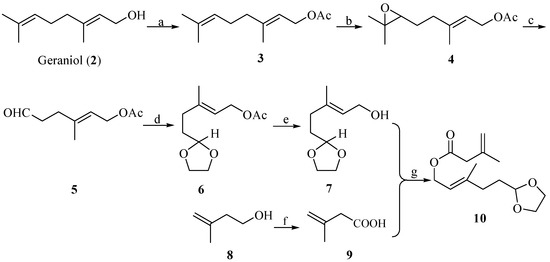

Our synthesis commenced with the construction of the key (E)-allylic ester intermediate 10 (Scheme 2). Protection of the hydroxyl group in geraniol (2) by acetyl chloride in pyridine gave 3 in 84% yield. Selective epoxidation of 3 at the double bond between C-6, C-7 with m-chloro- peroxybenzoic acid afforded 4 (72%), and the ring cleavage reaction was undertaken with periodic acid to afford aldehyde 5 (80%) [27,28]. Next, protection of the aldehyde group of 5 gave acetal 6 in 90% yield, and removal of the acetyl group of 6 with anhydrous potassium carbonate afforded alcohol 7 in 82% yield. The oxidation of 8 to acid 9 (58%) was achieved with Jones’ reagent. Finally, the subsequent esterification reaction of 7 and 9 in the presence of 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethyl-carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) (1 equiv.) and 4-dimethylaminepyridine (DMAP) (0.05 equiv.) gave the desired ester 10 in 42% yield.

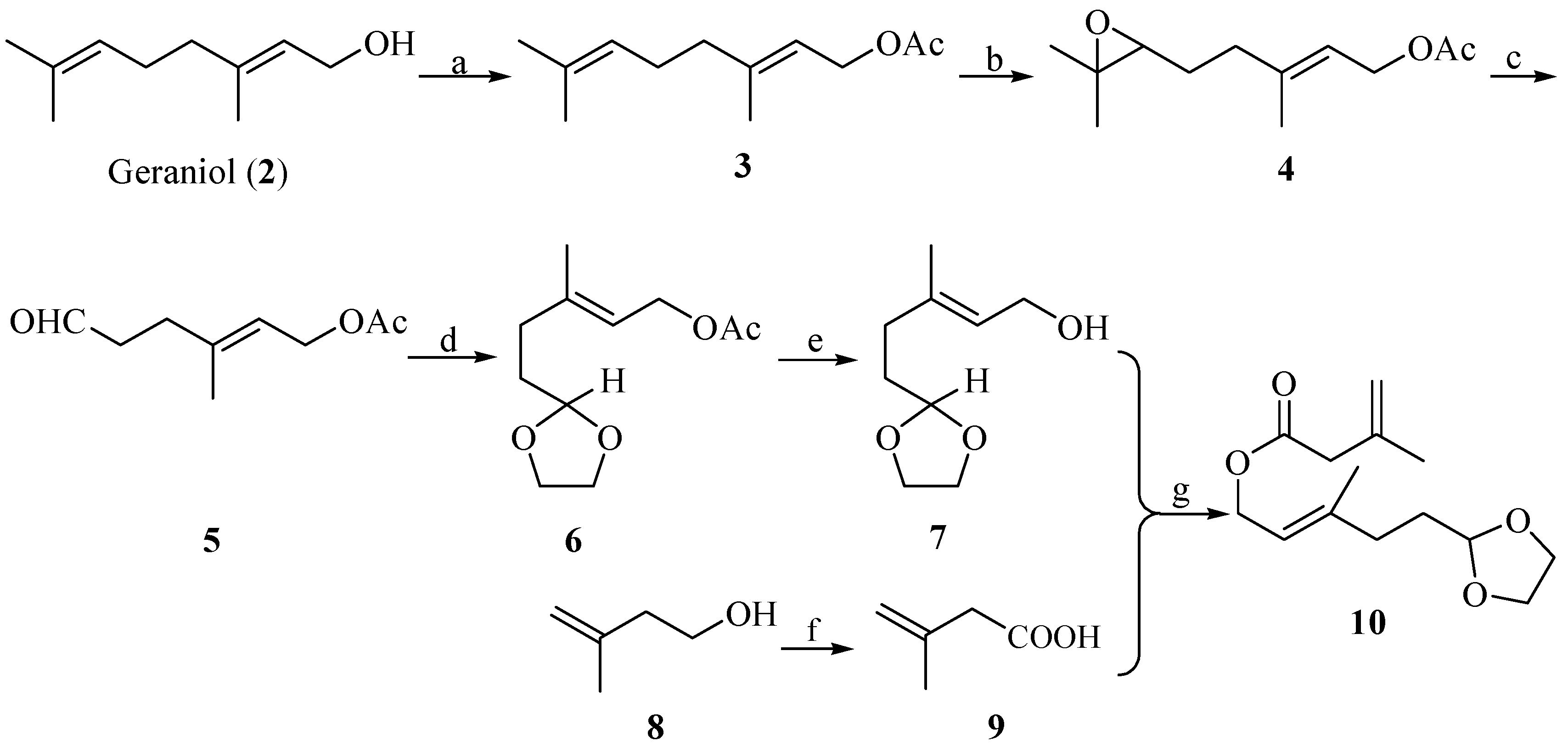

With ester 10 in hand, our first challenge was to construct the 1,2-dialkenyl moiety. We chose to accomplish this goal by the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement strategy. The rearrangement of ester 10 to acid 11 was conducted with lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) (2 equiv.) and chlorotrimethylsilane (TMSCl, 2 equiv.) at −78 °C in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran, followed by a conventional operation. A proposed mechanism according to Ireland-Claisen rearrangement was outlined in Scheme 3 [29]. The formation of preferential configuration of the (E)-silyl enol ether could help to rationalize the possible six-membered, acyclically advantage chair-like transition state. Further the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of the (E)-silyl enol ether afforded the syn- and anti-1, 2-dialkenyl moiety in acid 11 as a mixture inseparable by silica gel chromatography. From the 1H-NMR results, the diastereomeric ratio of anti 11a/syn 11b could be readily deduced from the double-double signals for the vinyl proton at δ 5.84/6.05 (J = 10.8, 17.5 Hz, -CH=). These 1H-NMR results were in agreement with those reported in the literature [21]. Koch et al. have demonstrated that the use of Lewis acid results in a highly diastereoselective rearrangement of allylic esters [30]. Thus, by using this protocol, we closely investigated the application of several Lewis acid catalysts to optimize the Claisen–Ireland rearrangement, and the results were summarized in Table 1. It was found that the anti diastereomer 11a was the major product (dr = 2:1, entry 1) when no Lewis acid catalyst was used, while the presence of various Lewis acids was unfavorable for improving the diastereoselectivity in this substrate. Other possible conditions to improve the diastereoselectivity were not screened.

Scheme 2.

Construction of the key intermediate (E)-allylic ester 10.

Scheme 2.

Construction of the key intermediate (E)-allylic ester 10.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CH3COCl, pyridine, 0 °C–r.t. (84%); (b) m-CPBA, CH2Cl2, −5–0 °C (72%); (c) HIO4·2H2O, THF, Et2O, 0 °C (80%); (d) glycol, benzene, p-TsOH(cat.), reflux, 5 h (90%); (e) K2CO3 (cat.), CH3OH, r.t., 12 h (82%); (f) Jones reagent (58%); (g) EDCI+DMAP (cat.), CH2Cl2, r.t, 12 h (42%).

Scheme 3.

Proposed advantage transition state of acid 11 from ester 10 via Ireland-Claisen rearrangement.

Scheme 3.

Proposed advantage transition state of acid 11 from ester 10 via Ireland-Claisen rearrangement.

Table 1.

Lewis acid-catalyzed Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of ester 10.

| Entry a | Lewis acid | Yield(%) b | dr c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 72% | 2:1 |

| 2 | TMSOTf | 94% | 1:1 |

| 3 | BF3-Et2O | 24% | 1:1 |

| 4 | ZnCl2 | 75% | 1:1 |

| 5 | SnCl4 | 91% | 1:1 |

a Reagents: Ester 10: LDA: TMSCl: Lewis acid = 1.0 equiv.: 2.0 equiv.: 2.0 equiv.: 0.1 equiv.; b Isolated yields from 10; c Diastereomeric ratio (anti/syn) was calculated by 1H-NMR analysis of the purified mixture 11.

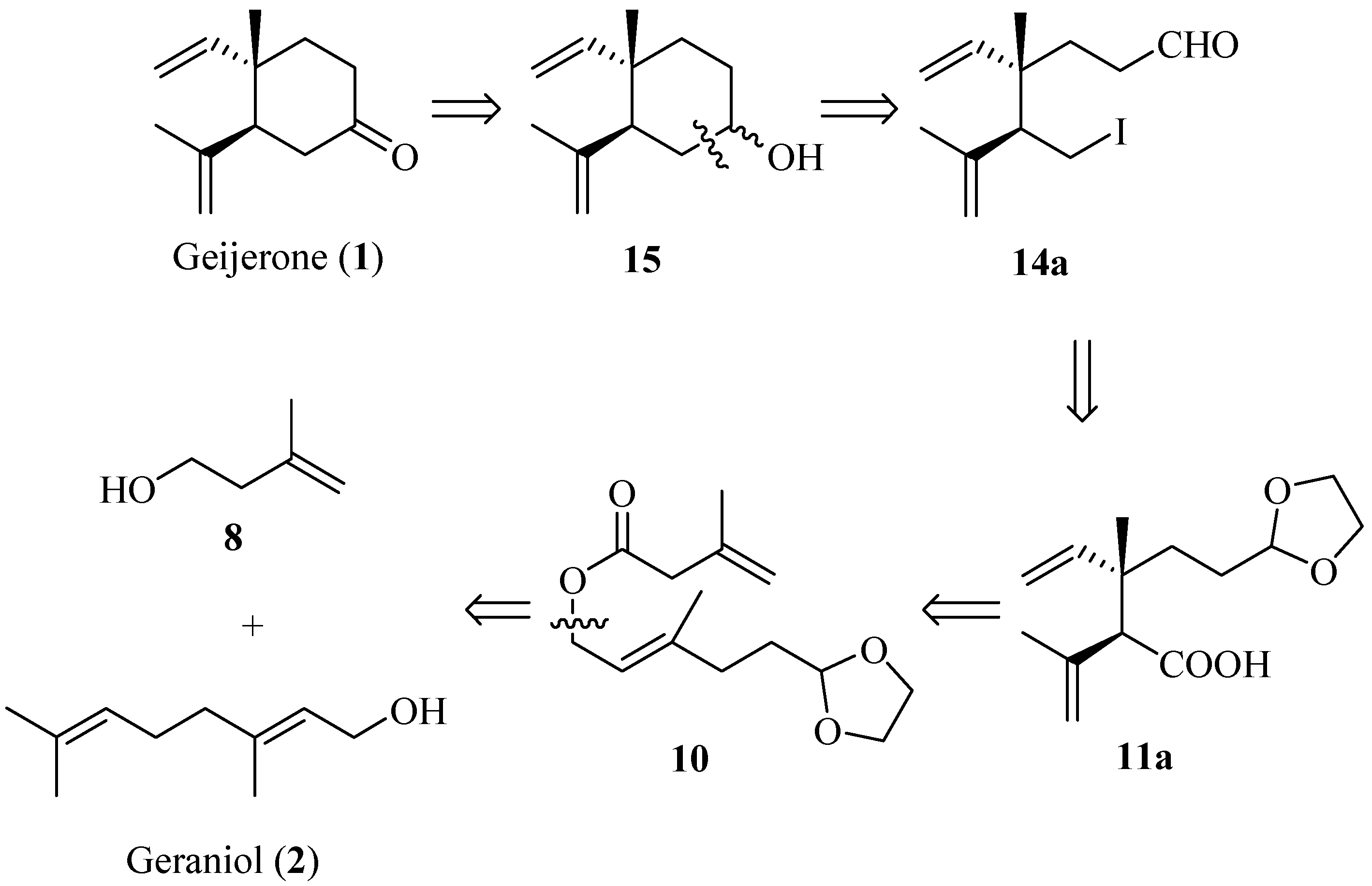

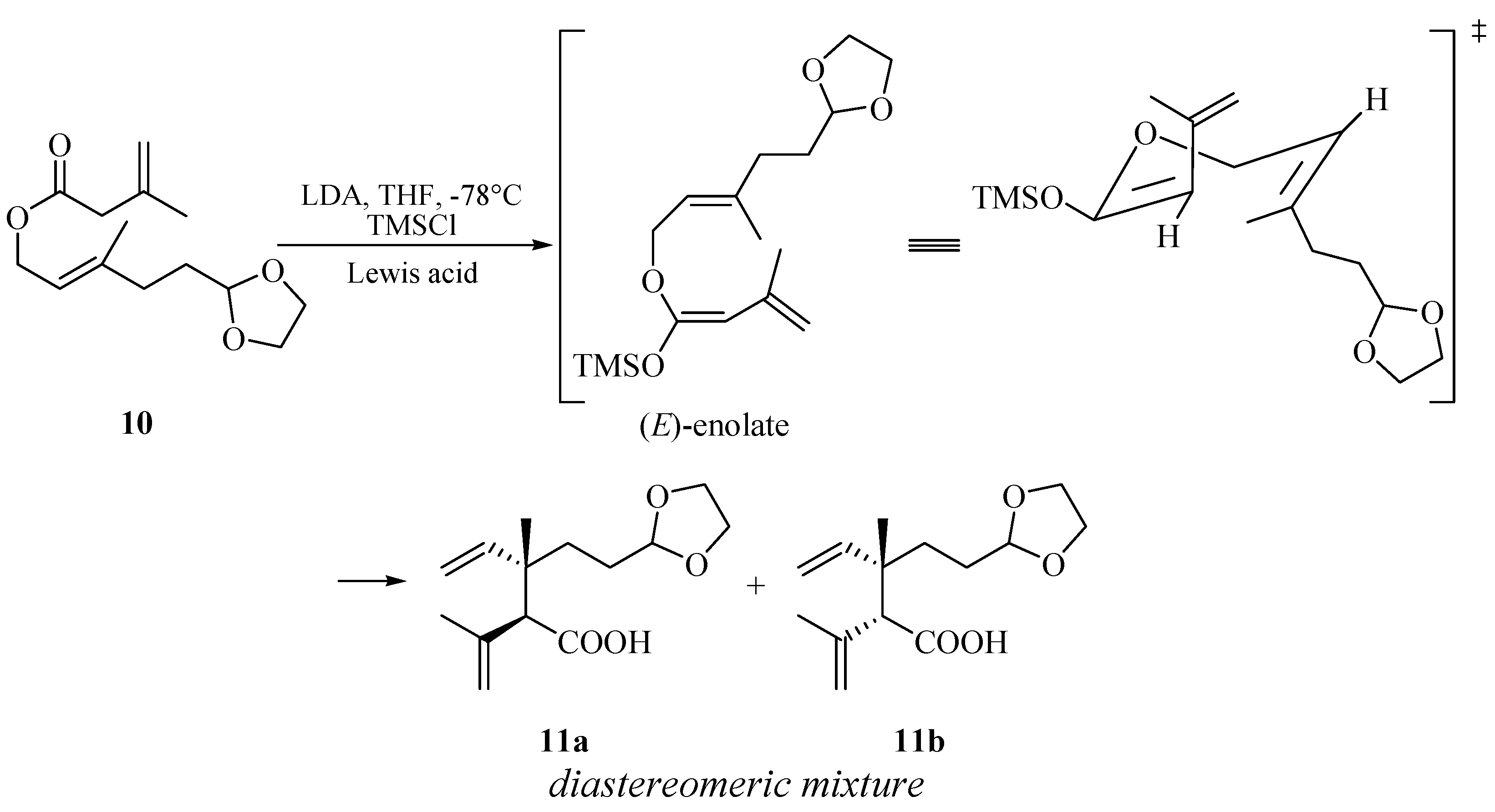

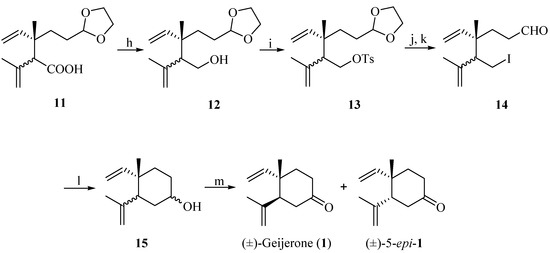

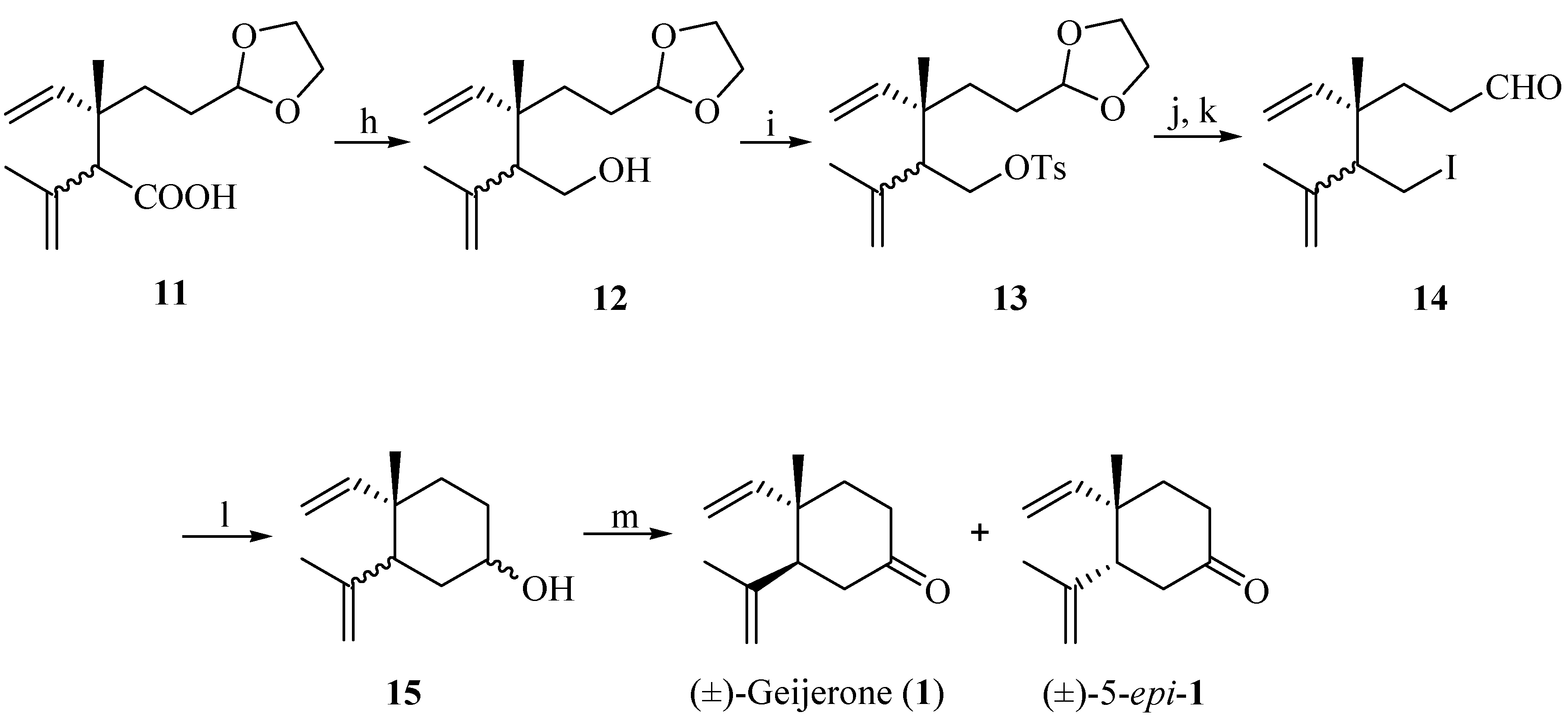

Subsequenr reduction of acid 11 with lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH4) gave a diastereomeric mixture of alcohols 12 in 83% yield. The diastereomeric separation of the mixture of alcohols was attempted by esterification of 12 with chiral O-acetyl mandelic acid, but the result was not ideal. Treatment of 12 with tosyl chloride gave a mixture of sulfonic esters 13, which after iodination and subsequent acetal deprotection provided a mixture of diastereoisomeric compounds 14, which was unstable during long-term storage. The diastereoisomers of 11–14 were difficult to separate by silica gel column chromatography, and various attempts to achieve the separation of the diastereoisomers using an appropriate chromatographic column size were undertaken. These methods have not been successful so far and the diastereomeric ratio of 14 was only raised to 3:1 (by 1H-NMR analysis). Subsequently, the cyclization of 14 occurred in the presence of n-BuLi via intramolecular Barbier reaction [31,32,33,34,35,36] to give a diastereomeric mixture of alcohols 15 (38%). The direct addition of n-BuLi to 14 might be the cause for the low yield. Further optimization of this reaction is not described in this communication. Finally, compound 15 was oxidized by pyridinium chlorochromate (PCC), affording a mixture of 1 and its 5-epimer (60%) (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of (±)-geijerone (1) and a diastereoisomeric mixture with its 5-epimer.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of (±)-geijerone (1) and a diastereoisomeric mixture with its 5-epimer.

Reagents and conditions: Reagents and conditions: (h) LiAlH4, THF, 0 °C–r.t. and reflux (83%); (i) p-TsCl, CH2Cl2, pyridine, r.t.; (j) NaI, acetone, reflux in the dark for 40 h; (k) p-TsOH (cat.), acetone (10%H2O), 1 h (23%, 3 steps); (l) n-BuLi, −78 °C (38%); (m) PCC, CH2Cl2, r.t., 2 h (60%).

3. Experimental

General Information

Several commercially available solvents were dried by standard procedures before use: pyridine (NaOH), THF (Na), acetonitrile (CaCl2). Other commercial sources were used without further purification. 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded with Bruker ARX-300 (300 MHz for 1H-NMR and 150 MHz for 13C-NMR) and Bruker ARX-600 spectrometers using TMS as internal standard (chemical shifts in δ values, J in Hz). Low-resolution MS and high-resolution MS data were obtained on Agilent-6120 Quadruple LC/MS and Agilent-6520 QTOF LC/MSD spectrometer, respectively, using ESI ionization. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel (200–300 mesh, Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd, Qingdao, China). Analytical TLC was performed on plates precoated with silica gel (GF254, 0.25 mm, Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd.) and iodine vapor was used to develop color on the plates.

3-Methyl-3-butenoic Acid (9). To a stirred solution of 8 (6.0 g, 69.7 mmol) in acetone (200 mL) the Jones reagent (36.5 mL, 97.5 mmol) was dropwise added at 0 °C for 2 h, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for another 6 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with H2O (50 mL), and most of acetone was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was extracted with Et2O (3 × 20 mL), The combined ethereal solution was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution. The combined aqueous layer was acidified with diluted hydrochloric acid (2 M) to pH = 3, and then extracted again with Et2O (2 × 20 mL). All combined ethereal solution was washed successively by water, brine and dried (anhydrous MgSO4), concentrated in vacuo. The residue was distilled to give 3.3 g (58%) of acid 9, colorless oil, b.p. = 86–88 °C (25 mmHg). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 10.14 (s, 1H, -COOH); 4.96 (dd, J = 1.5, 10.8 Hz, =CH2); 3.09 (s, 2H, -CH2-); 1.84 (s, 3H, -CH3).

(E)-3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dienyl Acetate (3). To a stirred solution of geraniol (2, 30.0 g, 194.8 mmol) in pyridine (80 mL) was added dropwise CH3COCl (16.5 mL) at 0 °C over 2 h, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The reaction mixture was poured to dilute hydrochloric acid solution (5%, 500 mL) and stirred for 30 min. The aqueous layer was extracted by EtOAc (3 × 30 mL) and the combined organic phases were washed successively by saturated aqueous NaHCO3, brine and dried (anhydrous MgSO4), The solution was concentrated under reduced pressure to yield 36.5 g (84%) acetate 3, colorless oil. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 5.37–5.32 (m, 1H, =CH-), 5.10-5.06 (m, 1H, =CH-), 4.59 (d, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, -CH2O-), 2.12-2.01 (m, 7H, -CH2CH2-, CH3CO-), 1.70 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.68 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.60 (s, 3H, -CH3). ESI-MS (m/z): 219.2 (M+Na)+.

(E)-5-(3,3-Dimethyloxiran-2-yl)-3-methylpent-2-enyl Acetate (4). A solution of m-chloroperbenzoic acid (85%, 18.1 g) in CH2Cl2 (160 mL) was added to a solution of 3 (15.0 g, 76.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (235 mL) at −5 °C over 2 h. The resulting mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h. The white precipitate was formed during the reaction (mainly m-chlorobenzoic acid). The reaction mixture was diluted with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (250 mL) and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 30 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, brine and dried (anhydrous MgSO4), and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was chromatographed on silica gel using 10% EtOAc/petroleum ether, affording 11.8 g (72%) of 4 as a colorless oil. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 5.42–5.37 (m, 1H, =CH-), 4.59 (d, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz,-CH2O-), 2.70 (t, 1H, J = 6.3 Hz, oxirane-H ), 2.26–2.13 (m, 2H, -CH2-), 2.05 (s, 3H, -CH3CO-), 1.73 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.70–1.63 (m, 2H, -CH2-), 1.31 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.26 (s, 3H, -CH3). ESI-MS (m/z): 235.2 (M+Na)+.

(E)-3-Methyl-6-oxohex-2-enyl acetate (5). To a stirred solution of 4 (5.0 g, 23.6 mmol) in Et2O (80 mL) was added dropwise HIO4∙2H2O (5.8 g, 25.4 mmol) in THF (50 mL) at 0 °C over 2 h. The resulting mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 3 h. Then the reaction mixture was diluted with water (100 mL) and the aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (2 × 30 mL). All organic phases were combined and washed successively by saturated aqueous NaHCO3, brine and dried (anhydrous MgSO4), and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was chromatographed on silica gel using 10% EtOAc/petroleum ether giving 3.2 g (80%) of 5 as a colorless oil. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 9.78 (s, 1H, -CHO), 5.39–5.34 (m, 1H, =CH-), 4.59 (d, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz, -CH2O-), 2.61–2.56 (m, 2H, -CH2-), 2.40–2.36 (m, 2H, -CH2-), 2.05 (s, 3H, CH3CO-), 1.73 (s, 3H, -CH3). ESI-MS (m/z): 193.1 (M+Na)+.

(E)-5-(1,3-Dioxolan-2-yl)-3-methylpent-2-enyl Acetate (6). A mixture of 5 (5.0 g, 29.4 mmol), ethylene glycol (2.7 g, 43.5 mmol), and p-TsOH (0.1 g, 0.6 mmol) in benzene (80 mL) was heated at reflux for 5 h. After the reaction was quenched with saturated NaHCO3 solution (40 mL) and the solvent was evaporated, the residue was partitioned between EtOAc (3 × 200 mL) and saturated aqueous NaCl (2 × 100 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and evaporated to give a residue which was purified by silica-gel chromatography (hexanes/EtOAc = 100:1) to afford 6 (5.7 g, 90%) as a yellow oil. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 5.40–5.35 (m, 1H, =CH-), 4.86 (t, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz, -OCH (-O-)CH2-), 4.58 (d, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, -CH2O-), 3.99–3.94 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 3.87–3.82 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 2.17 (t, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz, -CH2-), 2.05 (s, 3H, CH3CO-), 1.82–1.75 (m, 2H, -CH2-), 1.72 (s, 3H, -CH3). ESI-MS (m/z): 237.1 (M+Na)+.

(E)-5-(1,3-Dioxolan-2-yl)-3-methylpent-2-en-1-ol (7). A mixture of 6 (5.0 g, 23.4 mmol), and anhydrous K2CO3 (0.7 g, 5.0 mmol) in CH3OH (100 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 12 h (monitored by TLC, Rf = 0.5, EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1:1). Most of the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, the residue was diluted with water (30 mL) and extracted with Et2O (3 × 20 mL). The ethereal solution was combined and washed brine, dried (anhydrous MgSO4) and concentrated in vacuo to give the crude product, which was chromatographied over silica gel (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 20:80 → 40:60) to afford 3.4 g (82%) of 7 as a yellow oil. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 5.46–5.41 (m, 1H, =CH-), 4.86 (t, 1H, J = 4.7 Hz, -OCH(-O-)CH2-), 4.13 (d, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz, -CH2O-), 3.99–3.95 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 3.87–3.83 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 2.15 (t, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz, -CH2-), 1.85–1.75 (m, 2H, -CH2-), 2.05 (s, 3H, CH3CO-), 1.69 (s, 3H, -CH3). ESI-MS (m/z): 195.0 (M+Na)+.

(E)-5-(1,3-Dioxolan-2-yl)-3-methylpent-2-enyl 3-methylbut-3-enoate (10). A mixture of 7 (1.7 g, 10.0 mmol), 9 (1.0 g, 10.0 mmol), DCC (2.3 g, 12.0 mmol) and DMAP (0.3 g, 2.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (30 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 12 h (monitored by TLC, Rf = 0.8, EtOAc/petroleum ether = 1:5). The white precipitate was filtered, and the filtrate was washed successively by HCl (5%), saturated NaHCO3, brine, dried (anhydrous MgSO4) and concentrated in vacuo to give crude product, which was purified by silica-gel chromatography (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 5:95) to afford 1.1 g (42%) of 10 as light yellow oil. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 5.40–5.35 (m, 1H, =CH2), 4.91–4.62 (m, 3H, =CH2, =CH-, -OCH(-O-)CH2-), 4.62–4.60 (d, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz, -CH2O-), 3.99–3.95 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 3.87–3.82 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 3.03 (s, 2H, -CH2CO-), 2.17 (t, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz, -CH2-), 1.82 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.80-1.75 (m, 2H, -CH2-), 1.72 (s, 3H, -CH3). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 16.4, 22.3, 31.9, 33.5, 43.3, 61.3, 64.8, 103.9, 114.5, 118.4, 138.5, 141.4, 171.2. ESI-MS (m/z): 277.1 (M+Na)+. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C14H23O4 (M+H)+, 255.1596, found 255.1603.

(3S)-3-(2-(1,3-Dioxolan-2-yl)ethyl)-3-methyl-2-(prop-1-en-2-yl)pent-4-enoic Acid (11). A solution of 2 equiv. of LDA in dry THF (3 mL, 2 M) was cooled to −78 °C. To this stirred solution was added 1.0 equiv. of the ester 10 (0.76 g, 3 mmol), dropwise over 10 min. Following the addition, the reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 10 min and the 2 equiv. of Me3SiCl (0.76 mL, 6 mmol) in THF (6 mL) was added dropwisely to the reaction mixture for 10 min. The reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 1.5 h and allowed to warm to 25 °C for 2 h. After the reaction was quenched with 1 N NaOH (20 mL) and the organic phase was washed with 1 N NaOH (15 mL), the aqueous phases were combined and acidified by HCl (5%) to pH = 1. the mixture was extracted with Et2O (3 × 15 mL), dried with anhydrous MgSO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo to afford the crude acid, which was purified by silica gel chromatography (5% MeOH/CH2Cl2) to give 0.55 g (72%) of 11 as an inseparable mixture of diastereomers (dr = 2:1), as a light yellow oil. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ (mixture of two diastereomers) = 6.05 and 5.84 (dd, 1H, J = 10.8, 17.5 Hz, -CH=), 5.12–4.95 (m, 4H, =CH2, =CH2), 4.82 (t, 1H, J = 2.1 Hz, -OCH(-O-)CH2-), 3.97–3.89 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 3.85–3.81 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 3.06 (s, 1H, 4-H), 1.85 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.69–1.55 (m, 4H, -CH2CH2-), 1.16 and 1.11 (s, 1H, -CH3). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 19.4, 23.8/24.5, 28.8, 32.5/33.4, 42.0, 61.2/61.8, 63.6/64.8, 104.8, 114.0/114.3, 117.1/117.5, 139.7, 143.2/143.5, 177.4. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C14H23O4 (M+H)+, 255.1596, found 255.1564.

(3S)-3-(2-(1,3-Dioxolan-2-yl)ethyl)-3-methyl-2-(prop-1-en-2-yl)pent-4-en-1-ol (12). To a stirred solution of LiAlH4 (1.5 g, 39.3 mmol) in dry THF (15 mL) was added dropwise the inseparable mixture of 11 (2.0 g, 7.9 mmol) in dry THF (20 mL) at 0 °C over 10 min. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h and allowed to warm to reflux for 1 h. The mixture was quenched successively by H2O (1.5 mL), NaOH (15%, 1.5 mL) and 4.5 mL H2O on the ice-bath condition and stirred at room temperature for 30 min. The white precipitation was filtered and washed with Et2O (2 × 10 mL). All the organic phases were combined, dried (anhydrous MgSO4), filtered and concentrated in vacuo to give the crude product, which was purified by silica gel chromatography (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 5:95) to afford 1.58 g (83%) of 12 as an inseparable mixture of diastereomers (dr = 2:1), light yellow oil. Rf = 0.35 (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 1:3). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ (mixture of two diastereomers) = 5.77 and 5.72 (dd, 1H, J = 10.8, 17.5 Hz, -CH=), 5.11–4.79 (m, 5H, =CH2, =CH2, -OCH(-O-)CH2-), 3.95–3.93 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 3.85–3.83 (m, 2H, -OCH2-), 3.77–3.59 (m, 2H, -CH2OH), 2.25–2.22 (m, 1H, 4-H), 1.79 and 1.79 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.57–1.48 (m, 4H, -CH2CH2-), 1.03 and 0.98 (s, 1H, -CH3). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 17.7, 25.3, 28.5, 35.4, 41.1, 60.8/61.9, 62.4, 64.9/65.4, 102.2, 110.3, 113.1, 144.7, 149.7. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C14H25O3 (M+H)+, 241.1804, found 241.1794.

(3S)-5-(Iodomethyl)-4,6-dimethyl-4-vinylhept-6-enal (14). To a stirred solution of the inseparable mixture of 12 (1.3 g, 5.4 mmol) in dry pyridine (20 mL) was added dropwise tosyl chloride (1.5 g, 7.9 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) at ice-water temperature over 10 min. Then the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for additional 12 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with 10% HCl (30 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). All the organic phases were combined and washed successively by saturated NaHCO3, brine, and dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo to give the crude product 13, which was used directly in the next step without further purification. Rf = 0.60 (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 1:3). A solution of the inseparable mixture of 13, NaI (3.9 g) in acetone (25 mL) was allowed to reflux for 40 h in dark condition. After the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, the precipitation was filtered and concentrated to give brown oil, which was added saturated Na2S2O3 (30 mL) and extracted with ether (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic phases were washed by brine and dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo to give the crude iodide product, Rf = 0.80 (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 1:5). Then the solution of the crude iodide product, p-TsOH (0.1 g) in 10%H2O/acetone (10 mL) was allowed to reflux for 2 h. Most of acetone was evaporated in vacuo, the residue was diluted with saturated NaHCO3, and extracted with ether (3 × 10 mL). The combined ether was washed by brine, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered and concentrated to give the crude product, which was purified by silica gel chromatography (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 2:98) to afford inseparable mixture of 14 (0.38 g, 23% in 3 steps). light yellow oil. Rf = 0.50 (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 1:8). Trials were performed to establish the separability of the diastereoisomers using an appropriate chromatographic column size. These attempts have not been successful so far and the diastereomeric ratio of 14 was only raised to 3:1. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ (mixture of two diastereomers) = 5.71 and 5.64 (dd, 1H, J = 10.8, 17.4 Hz, -CH=), 5.22-4.79 (m, 4H, =CH2, =CH2), 3.53–3.49 (m, 1H, -CH2I), 3.15–3.06 (m, 1H, -CH2I), 2.45–2.30 (m, 3H, -CH2CHO and 5-H), 1.65–1.82 (m, 5H, -CH2-, -CH3), 1.04 and 0.97 (s, 1H, -CH3). HRMS (ESI): calcd for C12H20IO (M+H)+, 307.0559, found 307.0941.

(±)-Geijerone (1) and its 5-epimer. A solution of the inseparable mixture of 14 (0.5 g, 1.6 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL) was cooled to −78 °C. To this stirred solution was added dropwise 3.0 equiv. of n-BuLi (1.6 M/L in n-hexane, 3.1 mL, 4.8 mmol) over 10 min. The reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for additional 1 h. Then the reaction mixture was quenched with saturated NH4Cl (30 mL), and the organic phase was separated. The aqueous phase was extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL). All organic phases were combined and washed by brine and dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo to afford inseparable diastereomeric mixture of crude 15, light yellow oil. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C12H21O (M+H)+, 181.1592, found 181.1584.

A solution of the inseparable mixture of 15 (70 mg, 0.6 mmol) in 10 mL of CH2Cl2 was added dropwise PCC (0.5 g, 2.3 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) at room temperature over 10 min, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for additional 2 h. Then the reaction mixture was diluted with 10 mL of diethyl ether, filtered and concentrated in vacuo to give the crude product, which was purified by silica gel chromatography (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 2:98) to afford an inseparable diastereomeric mixture of 1 and its 5-epimer (40 mg, 60%), colorless oil. Rf = 0.75 (EtOAc/petroleum ether, 1:6). 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ (as a mixture with 5-epimer) = 5.75 and 5.65 (dd, 1H, J = 10.6, 17.3 Hz, 1-H), 5.11–4.65 (m, 4H, 2-H, 3-H), 2.60–2.25 (m, 4H, 6-H, 8-H), 1.78–1.63 (m, 3H, 5-H, 11-H), 1.56–1.48 and 1.36–1.23 (m, 2H, 9-H), 0.91 and 0.90 (s, 3H, 12-H). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 13.9, 22.4/26.0, 27.7/29.7, 32.3/32.4, 38.1, 42.7, 56.1/57.4, 112.6/112.7, 113.7/114.3, 143.8/144.7, 144.8/145.7, 211.8/211.9. ESI-MS (m/z): 201.1 (M+Na)+. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C12H19O (M+H)+, 179.1436, found 179.1400.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, an alternative synthetic route of both diastereomers of (±)-geijerone (1) via a 13-step process was achieved starting from the commercially available geraniol (2). The Ireland-Claisen rearrangement (10→11) bearing the syn- and anti-1,2-dialkenyl carboxylic acid, and the intramolecular Barbier reaction affording the new intramolecular C-C bond (15) were the key steps. The newly formed syn- and anti-1,2-dialkenylcyclohexane strategy used for the synthesis of (±)-geijerone (1) and a diastereoisomeric mixture with its 5-epimer allows rapid access to various epimers and analogues of elemene-type products.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Key Technologies R&D Program of China (2009ZX09103-057), Program for Innovative Research Team of the Ministry of Education and Program for Liaoning Innovative Research Team in University (IRT1073).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Jinhua Dong, Dawei Liang. Performed the experiments: Dawei Liang, Nana Gao and Wei Liu. Analyzed the data: Dawei Liang, Jinhua Dong. Wrote the paper: Dawei Liang, Jinhua Dong.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Newman, D.J. Natural products as leads to potential drugs: An old process or the new hope for drug discovery? J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2589–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Sawamura, M. Effects of storage conditions on the composition of Citrus tamurana Hort. ex Tanaka (hyuganatsu) essential oil. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweka, E.J.; Nyindo, M.; Mosha, F.; Silva, A.G. Insecticidal activity of the essential oil from fruits and seeds of Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi against African malaria vectors. Parasite. Vector. 2011, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djabou, N.; Allali, H.; Battesti, M.J.; Tabti, B.; Costa, J.; Muselli, A.; Varesi, L. Chemical and genetic differentiation of two Mediterranean subspecies of Teucrium scorodonia L. Phytochemistry 2011, 74, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, A.J.; Grimshaw, J.; Penfold, A.R.; Sheppard, N.; Speake, R.N. An independent confirmation of the structure of geijerene by physical methods. J. Chem. Soc. 1961, 2286–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.C.; Wang, S.K.; Dai, C.F.; Duh, C.Y. A cytotoxic lobane diterpene from the formosan soft coral Sinularia inelegans. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 843–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, Y.; Yamamura, S. Stereochemical studies on germacrenes: An application of molecular mechanics calculations. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 35, 3303–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, Y.; Yamamura, S. An Application of molecular mechanics calculations on thermal reactions of ten-membered ring Sesquit. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1982, 55, 2495–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.B.; Yamamoto, R.E.; Zanoli, K.; Nocchi, S.R.; Novello, C.R.; Schuquel, I.T.A.; Sakuragui, C.M.; Luftmann, H.; Ueda-Nakamura, T.; Nakamura, C.V.; et al. Evaluation of the antiproliferative activity of the leaves from Arctium lappa by a bioassay-guided fractionation. Molecules 2012, 17, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, X.S.; Yu, L.L.; Zheng, S. The antitumor activity of elemene is associated with apoptosis. Chin. J. Oncol. 1996, 18, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Abraham, A.; Bhat, B.; Jaggi, M.; Singh, A.T.; Sanna, V.K.; Singh, G.; Agarwal, S.K.; Mukherjee, R.; Burman, A.C. Synthesis of 13-amino costunolide derivatives as anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 4195–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.G.; Kwak, E.Y.; Chung, B.H.; Cho, W.J.; Cheon, S.H. Synthesis of sesquiterpene derivatives as potential antitumor agents; elemane derivatives. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1999, 22, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, J.L.; Xu, L.; Hou, K.Z.; Zhang, J.D.; Qu, X.J.; Liu, Y.P. â-Elemene-induced autophagy protects human gastric cancer cells from undergoing apoptosis. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lu, Y.; Wu, J.; Gao, M.; Wang, A.; Xu, B. Beta-elemene inhibits melanoma growth and metastasis via suppressing vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated angiogenesis. Cancer Chemoth. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.Y.; Yang, W.; Ying, J.; Ni, Q.C.; Pan, X.D.; Dong, J.H.; Li, K.; Wang, X.S. B-Cell Lymphoma-2 over-expression protects ä-elemene-induced apoptosis in human lung carcinoma mucoepidermoid cells via a nuclear factor Kappa B-related pathway. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W. Elemene: Antineoplastic. Drugs Future 1998, 23, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.J.; Shao, J.L.; Zhang, Z.L.; Ao, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, M.; Chen, T. Pharmacological studies on elemene and the clinical application. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 2001, 12, 1123–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.B.; Zhao, Y.F.; Song, G.Q.; Wu, Y.L. Double michael reaction of carvone and its derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 3559–3562. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.F.; Zhao, R.B.; Wu, Y.L. Double michael reaction of carvone and its utilization in chiral synthesis of natural products. Huaxue Xuebao 1994, 52, 823–830. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, L.J.; Rao, A.S. Synthesis of â-elemene and elemol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 8, 2273–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurry, J.E.; Kocovsky, P. Synthesis of helminthogermacrene and â-elemene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 2171–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, E.J.; Roberts, B.E.; Dixon, B.R. Enantioselective total synthesis of â-elemene and fuscol based on enantiocontrolled Ireland-Claisen rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Chang, J.; Kim, S. Stereoselective synthesis of (±)-â-elemene by a doubly diastereodifferentiating internal alkylation: A remarkable difference in the rate of enolization between syn and anti esters. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, A.F.; Herrador, M.M.; Quílez del Moral, J.F.; Arteaga, P.; Meine, N.; Pérez-Morales, M.C.; Catalán, J.V. Efficient synthesis of the anticancer â-elemene and other bioactive elemanes from sustainable germacrone. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Kim, H.S. Stereoselective construction of functionalized cis-1,2-dialkyl-cyclo-hexanecarboxylates: A novel synthesis of (±)-geijerone and ã-elemene. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 4633–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Kurihara, H.; Yoshikoshi, A. Total synthesis of racemic geijerone and ã-elemene. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1979, 2740–2743. [Google Scholar]

- Kodd, D.S.; Oehlschlager, A.C.; Georgopapadakou, N.H.; Polak, A.M.; Hartman, P.G. Synthesis of inhibitors of 2,3-oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase. 2. Cyclocondensation of ã-, ä-unsaturated â-keto esters with imines. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 7226–7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.E.; Bailey, J.L.; Lockner, J.W.; Coates, R.M. Regio- and stereoselectivity of diethylaluminum azide opening of trisubstituted epoxides and conversion of the 3° azidohydrin adducts to isoprenoid aziridines. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.E.; Mueller, R.H.; Willard, A.K. The ester enolate Claisen rearrangement. Stereochemical control through stereoselective enolate formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 2868–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; Janser, P.; Kottirsch, G.; Romero-Giron, E. Highly diastereoselective Lewis acid promoted Claisen-Ireland rearrangement. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 4837–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, M.P., Jr.; Houpis, I.N. Metal-halogen exchange-initiated cyclization of iodo carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 4987–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, M.; Kashimoto, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kobayashi, S. A new intramolecular Barbier reaction of N-(2-iodobenzyl)phenacylamines: A convenient synthesis of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinomn-4-ols. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 5347–5348. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Dowd, P. Intramolecular Barbier reaction of a 3-(3'-bromopropyl) bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-5-en-2-one. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 2095–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón, D.J.; Yus, M. Carbamoyl and thiocarbamoyl lithium: A new route by naphthalene-catalysed chlorine-lithium exchange. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 7115–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, D.S.; Lathbury, D.C.; Wanders, A.; Watts, D. Scale-up of an intermolecular Barbier Reaction. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 1998, 2, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Takeuchi, T.; Matsuhashi, M.; Nakata, T. Chromone derivatives from the leaves of Nicotiana tabacum and their anti-Tobacco Mosaic Virus Activities. Heterocycles 2007, 72, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 1, 3–7, 9–12 and 14 are available from the authors.

© 2014 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).