Microbial Glycosylation of Daidzein, Genistein and Biochanin A: Two New Glucosides of Biochanin A

Abstract

:1. Introduction

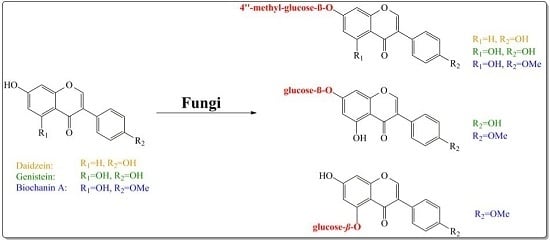

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Compounds

3.2. Biotransformation

3.2.1. Microorganisms

3.2.2. Screening Procedure

3.2.3. Preparative (Large) Scale Biotransformation

3.3. Analysis of Products with High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

3.4. Identification of the Products

3.5. Obtained Biotransformation Products

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adlercreutz, H. Phytoestrogens: Epidemiology and a possible role in cancer protection. Environ. Health Perspect. 1995, 103, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.J.; Murphy, P.A. Isoflavone content in commercial soybean foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 42, 1666–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.R. Prevention of carcinogenesis by protease inhibitors. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 1999–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, D.F.; Hendrich, S.; Wang, W. Dietary agents in cancer prevention: Flavonoids and isoflavonoids. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 90, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varinska, L.; Gal, P.; Mojzisova, G.; Mirossay, L.; Mojzis, J. Soy and breast cancer: Focus on angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 11728–11749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uifălean, A.; Schneider, S.; Gierok, P.; Ionescu, C.; Iuga, C.A.; Lalk, M. The impact of soy isoflavones on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells using a global metabolomic approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siow, R.C.M.; Mann, G.E. Dietary isoflavones and vascular protection: Activation of cellular antioxidant defenses by SERMs or hormesis? Mol. Asp. Med. 2010, 31, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Penalvo, J.L.; Gil, J.I.; Medina, S.; Horcajada, M.N.; Lafay, S.; Silberberg, M.; Llorach, R.; Zafrilla, P.; Garcia-Mora, P.; et al. Soy isoflavones and cardiovascular disease epidemiological, clinical and -omics perspectives. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelo-Branco, C.; Cancelo Hidalgo, M.J. Isoflavones: Effects on bone health. Climacteric 2011, 14, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, L.G.; Howes, J.B.; Knight, D.C. Isoflavone therapy for menopausal flushes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2006, 55, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somekawa, Y.; Chiguchi, M.; Ishibashi, T.; Aso, T. Soy intake related to menopausal symptoms, serum lipids, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Japanese women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sordon, S.; Popłoński, J.; Huszcza, E. Microbial glycosylation of flavonoids. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2016, 65, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollman, P.C.; Bijsman, M.N.; van Gameren, Y.; Cnossen, E.P.; de Vries, J.H.; Katan, M.B. The sugar moiety is a major determinant of the absorption of dietary flavonoid glycosides in man. Free Radic. Res. 1999, 3, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollman, P.C.; Katan, M.B. Absorption, metabolism and health effects of dietary flavonoids in man. Biomed. Pharmacother. 1997, 51, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskula, M.K.; Yamakoshi, J.; Iwai, Y. Daidzein and genistein but not their glucosides are absorbed from the rat stomach. FEBS Lett. 1999, 447, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespy, V.; Morand, C.; Besson, C.; Manach, C.; Demigne, C.; Remesy, C. Quercetin, but not its glycosides, is absorbed from the rat stomach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornard, J.P.; Boudet, A.C.; Merlin, J.C. Theoretical investigation of the molecular structure of the isoquercitrin molecule. J. Mol. Struct. 1999, 508, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wach, A.; Pyrzynska, K.; Biesaga, M. Quercetin content in some food and herbal samples. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Zuo, Z.; Chow, M.S.S.; Ho, W.K.K. Difference in absorption of the two structurally similar flavonoid glycosides, hyperoside and isoquercitrin in rats. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2005, 59, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, T.; Piskula, M.K.; Osawa, S.; Obata, A.; Tobe, K.; Saito, M.; Kataoka, S.; Kubota, Y.; Kikuchi, M. Soy isoflavone aglycones are absorbed faster and in higher amounts than their glucosides in humans. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1695–1699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Setchell, K.D.R.; Brown, N.M.; Desai, P.; Zimmer-Nechemias, L.; Wolfe, B.E.; Brashear, W.T.; Kirschner, A.S.; Cassidy, A.; Heubi, J.E. Bioavailability of pure isoflavones in healthy humans and analysis of commercial soy isoflavone supplements. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1362–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Bartmańska, A.; Huszcza, E.; Tronina, T. Transformation of isoxanthohumol by fungi. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2009, 61, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartmańska, A.; Tronina, T.; Huszcza, E. Transformation of 8-prenylnaringenin by Absidia coerulea and Beauveria bassiana. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 6451–6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tronina, T.; Bartmańska, A.; Milczarek, M.; Wietrzyk, J.; Popłoński, J.; Rój, E.; Huszcza, E. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of glycosides obtained by biotransformation of xanthohumol. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 1957–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.L.; He, Y.Q.; Huang, B.; Li, C.R.; Fan, M.Z.; Li, Z.Z. Secondary metabolites in a soybean fermentation broth of Paecilomyces militaris. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Wu, X.; Li, B.; He, B. Efficient glucosylation of flavonoids by organic solvent-tolerant Staphylococcus saprophyticus CQ16 in aqueous hydrophilic media. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2014, 99, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, K.; Kubota, N.; Hamada, H.; Hamada, H. Synthesis of gentiooligosaccharides of genistein and glycitein and their radical scavenging and anti-allergic activity. Molecules 2011, 16, 4740–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Kaltia, S.; Wähälä, K. The phase transfer catalyzed synthesis of isoflavone-O-glucosides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1998, 2481–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Laval, S.; Yu, B. Glycosylation reactions in the synthesis of flavonoid glycosides. Synthesis 2014, 46, 1030–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, F.L.; Yang, L.M.; Chang, S.F.; Wang, L.H.; Hsu, C.Y.; Liu, P.C.; Lin, S.J. Biotransformation of gallic acid by Beauveria sulfurescens ATCC 7159. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S. Glycosylation of (−)-maackiain by Beauveria bassiana and Cunninghamella echinulata var. elegans. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2010, 28, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Gunatilaka, L. Selective 4′-O-methylglycosylation of the pentahydroxy-flavonoid quercetin by Beauveria bassiana ATCC 7159. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2006, 24, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, P.; Rasini, E.; Luini, A.; Legnaro, M.; Luzzani, M.; Casareto, E.; Carreri, M.; Paracchini, S.; Marino, F.; Cosentino, M. Isoflavone content and estrogenic activity of different batches of red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) extracts: An in vitro study in MCF-7 cells. Fitoterapia 2014, 94, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crozier, A.; del Rio, D.; Clifford, M.N. Bioavailability of dietary flavonoids and phenolic compounds. Mol. Asp. Med. 2010, 31, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, Y.; Sagawa, K.; Frederick, K.; Zhang, S.; Morris, M.E. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of the isoflavone biochanin A in rats. AAPS J. 2006, 8, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh Wahajuddin, S.P. Intravenous pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of biochanin A in female rats. Med. Chem. Res. 2011, 20, 1627–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.K.; Lee, B.J.; Lee, H.K. Enhanced dissolution and bioavailability of biochanin A via the preparation of solid dispersion: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 415, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utkina, E.A.; Antoshina, S.V.; Selishcheva, A.A.; Sorokoumova, G.M.; Rogozhkina, E.A.; Shvets, V.I. Isoflavones daidzein and genistein: Preparation by acid hydrolysis of their glycosides and the effect on phospholipid peroxidation. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2004, 30, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrachim, M.; Ambreen, S.; Hussain, A.; Hussain, N.; Imran, M.; Ali, B.; Sumrra, S.; Yousuf, H.M.; Rehmani, F.S. Phytochemical investigation on Eucalyptus globulus Labill. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 1011–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, Q.C.; Huang, R.; Miao, C.P.; Chen, Y.W.; Zhai, Y.Z.; Song, F.; Wang, T.; Wu, S.H. Secondary metabolites of endophytic fungus. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2014, 50, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, P.L.; Kudo, S.; Okubo, K.K. Isoflavonoids. In Handbook of Plant and Fungal Toxicants, 2nd ed.; Felix D’Mello, J.P., Ed.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Ilić, S.B.; Konstantinović, S.S.; Todorović, Z.B. Flavonoids from flower of Linum Capitatum Kit UDC 547.972.2. Ser. Phys. Chem. Technol. 2004, 3, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, L.; Gao, P.; Shao, Z. Isolation and characterization of the isoflavones from sprouted chickpea seeds. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds daidzein, 4″-O-methyldaidzin, biochanin A, sissotrin and isosissotrin, 4″-O-methylsissotrin are available from the authors.

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sordon, S.; Popłoński, J.; Tronina, T.; Huszcza, E. Microbial Glycosylation of Daidzein, Genistein and Biochanin A: Two New Glucosides of Biochanin A. Molecules 2017, 22, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22010081

Sordon S, Popłoński J, Tronina T, Huszcza E. Microbial Glycosylation of Daidzein, Genistein and Biochanin A: Two New Glucosides of Biochanin A. Molecules. 2017; 22(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleSordon, Sandra, Jarosław Popłoński, Tomasz Tronina, and Ewa Huszcza. 2017. "Microbial Glycosylation of Daidzein, Genistein and Biochanin A: Two New Glucosides of Biochanin A" Molecules 22, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22010081

APA StyleSordon, S., Popłoński, J., Tronina, T., & Huszcza, E. (2017). Microbial Glycosylation of Daidzein, Genistein and Biochanin A: Two New Glucosides of Biochanin A. Molecules, 22(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22010081