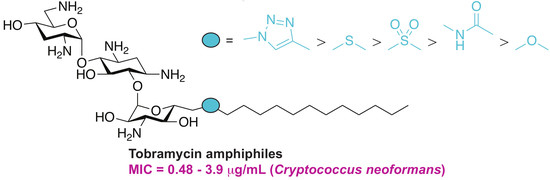

Differential Effects of Linkers on the Activity of Amphiphilic Tobramycin Antifungals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. In Vitro Antifungal Activity

2.3. Hemolysis

2.4. Cytotoxicity

2.5. Time-Kill Studies

2.6. Antifungal Mechanism of Action

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Information

4.2. Synthesis of Compounds 2–16

4.3. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

4.4. Hemolytic Activity Assays

4.5. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assays

4.6. Time-Kill Assays

4.7. Membrane Permeabilization Assay Using Propidium Iodide Staining

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AcOH | acetic acid |

| AG | aminoglycoside |

| AmB | amphotericin B |

| Boc2O | di-tert-butyl dicarbonate |

| CAS | caspofungin |

| CFU | colony forming unit |

| DIPEA | N,N-diisopropylamine |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| EDC·HCl | N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride |

| FDA | US food and drug administration |

| HOBt | hydroxybenzotriazole |

| KANA | kanamycin A |

| KANB | kanamycin B |

| m-CPBA | meta-chloroperbenzoic acid |

| mRBC | murine red blood cell |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| PivCl | pivaloyl chloride |

| TBAA | tetrabutylammonium azide |

| TFA | trifluoroacetic acid |

| Tf2O | trifluoromethane sulfonic anhydride |

| THF | tetrahydrofuran |

| TIPBSCl | 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl chloride |

| TOB | tobramycin |

| VOR | voriconazole |

References

- Houghton, J.L.; Green, K.D.; Chen, W.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. The future of aminoglycosides: The end or renaissance? ChemBioChem 2010, 11, 880–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garneau-Tsodikova, S.; Labby, K.J. Mechanisms of resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics: Overview and perspectives. MedChemComm 2016, 7, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamban Chandrika, N.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Comprehensive review of chemical strategies for the preparation of new aminoglycosides and their biological activities. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1189–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorityala, B.K.; Guchhait, G.; Schweizer, F. Amphiphilic aminoglycoside antimicrobials in antibacterial discovery. In Carbohydrates in Drug Design and Discovery; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 255–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bera, S.; Zhanel, G.G.; Schweizer, F. Antibacterial activities of aminoglycoside antibiotics-derived cationic amphiphiles. Polyol-modified neomycin B-, kanamycin A-, amikacin-, and neamine-based amphiphiles with potent broad spectrum antibacterial activity. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3626–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhondikubeer, R.; Bera, S.; Zhanel, G.G.; Schweizer, F. Antibacterial activity of amphiphilic tobramycin. J. Antibiot. 2012, 65, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkov-Zrihen, Y.; Herzog, I.M.; Benhamou, R.I.; Feldman, M.; Steinbuch, K.B.; Shaul, P.; Lerer, S.; Eldar, A.; Fridman, M. Tobramycin and nebramine as pseudo-oligosaccharide scaffolds for the development of antimicrobial cationic amphiphiles. Chemistry 2015, 21, 4340–4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, I.M.; Green, K.D.; Berkov-Zrihen, Y.; Feldman, M.; Vidavski, R.R.; Eldar-Boock, A.; Satchi-Fainaro, R.; Eldar, A.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S.; Fridman, M. 6″-thioether tobramycin analogues: Towards selective targeting of bacterial membranes. Angew. Chem. 2012, 51, 5652–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guchhait, G.; Altieri, A.; Gorityala, B.; Yang, X.; Findlay, B.; Zhanel, G.G.; Mookherjee, N.; Schweizer, F. Amphiphilic tobramycins with immunomodulatory properties. Angew. Chem. 2015, 54, 6278–8622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosso, M.Y.; Zhu, H.; Green, K.D.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S.; Fredrick, K. Tobramycin variants with enhanced ribosome-targeting activity. ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, I.M.; Feldman, M.; Eldar-Boock, A.; Satchi-Fainaro, R.; Fridman, M. Design of membrane targeting tobramycin-based cationic amphiphiles with reduced hemolytic activity. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baussanne, I.; Bussiere, A.; Halder, S.; Ganem-Elbaz, C.; Ouberai, M.; Riou, M.; Paris, J.M.; Ennifar, E.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.P.; Decout, J.L. Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of amphiphilic neamine derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouberai, M.; El Garch, F.; Bussiere, A.; Riou, M.; Alsteens, D.; Lins, L.; Baussanne, I.; Dufrene, Y.F.; Brasseur, R.; Decout, J.L.; et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa membranes: A target for a new amphiphilic aminoglycoside derivative? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1808, 1716–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sautrey, G.; Zimmermann, L.; Deleu, M.; Delbar, A.; Souza Machado, L.; Jeannot, K.; Van Bambeke, F.; Buyck, J.M.; Decout, J.L.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.P. New amphiphilic neamine derivatives active against resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their interactions with lipopolysaccharides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4420–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, S.; Zhanel, G.G.; Schweizer, F. Design, synthesis, and antibacterial activities of neomycin-lipid conjugates: Polycationic lipids with potent gram-positive activity. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 6160–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chiang, F.I.; Wu, L.; Czyryca, P.G.; Li, D.; Chang, C.W. Surprising alteration of antibacterial activity of 5″-modified neomycin against resistant bacteria. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7563–7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Keller, K.; Takemoto, J.Y.; Bensaci, M.; Litke, A.; Czyryca, P.G.; Chang, C.W. Synthesis and combinational antibacterial study of 5″-modified neomycin. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, S.; Dhondikubeer, R.; Findlay, B.; Zhanel, G.G.; Schweizer, F. Synthesis and antibacterial activities of amphiphilic neomycin B-based bilipid conjugates and fluorinated neomycin B-based lipids. Molecules 2012, 17, 9129–9141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udumula, V.; Ham, Y.W.; Fosso, M.Y.; Chan, K.Y.; Rai, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Chang, C.W. Investigation of antibacterial mode of action for traditional and amphiphilic aminoglycosides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 1671–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francois, B.; Szychowski, J.; Adhikari, S.S.; Pachamuthu, K.; Swayze, E.E.; Griffey, R.H.; Migawa, M.T.; Westhof, E.; Hanessian, S. Antibacterial aminoglycosides with a modified mode of binding to the ribosomal-RNA decoding site. Angew. Chem. 2004, 43, 6735–6738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkov-Zrihen, Y.; Herzog, I.M.; Feldman, M.; Fridman, M. Site-selective displacement of tobramycin hydroxyls for preparation of antimicrobial cationic amphiphiles. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 6144–6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bera, S.; Zhanel, G.G.; Schweizer, F. Antibacterial activity of guanidinylated neomycin B- and kanamycin A-derived amphiphilic lipid conjugates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 1224–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosso, M.Y.; Shrestha, S.K.; Green, K.D.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Synthesis and bioactivities of kanamycin B-derived cationic amphiphiles. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 9124–9132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosso, M.Y.; Li, Y.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. New trends in aminoglycosides use. MedChemComm 2014, 5, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.W.; Fosso, M.; Kawasaki, Y.; Shrestha, S.; Bensaci, M.F.; Wang, J.; Evans, C.K.; Takemoto, J.Y. Antibacterial to antifungal conversion of neamine aminoglycosides through alkyl modification. Strategy for reviving old drugs into agrofungicides. J. Antibiot. 2010, 63, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.; Grilley, M.; Fosso, M.Y.; Chang, C.W.; Takemoto, J.Y. Membrane lipid-modulated mechanism of action and non-cytotoxicity of novel fungicide aminoglycoside FG08. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.W.; Takemoto, J.Y. Antifungal amphiphilic aminoglycosides. MedChemComm 2014, 5, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosso, M.; AlFindee, M.N.; Zhang, Q.; Nziko Vde, P.; Kawasaki, Y.; Shrestha, S.K.; Bearss, J.; Gregory, R.; Takemoto, J.Y.; Chang, C.W. Structure-activity relationships for antibacterial to antifungal conversion of kanamycin to amphiphilic analogues. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 4398–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.K.; Fosso, M.Y.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. A combination approach to treating fungal infections. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.K.; Chang, C.W.; Meissner, N.; Oblad, J.; Shrestha, J.P.; Sorensen, K.N.; Grilley, M.M.; Takemoto, J.Y. Antifungal amphiphilic aminoglycoside K20: Bioactivities and mechanism of action. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, N.; Wright, G.D.; Cowen, L.E. Antifungal drugs: The current armamentarium and development of new agents. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.M.; Clay, M.C.; Cioffi, A.G.; Diaz, K.A.; Hisao, G.S.; Tuttle, M.D.; Nieuwkoop, A.J.; Comellas, G.; Maryum, N.; Wang, S.; et al. Amphotericin forms an extramembranous and fungicidal sterol sponge. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghannoum, M.A.; Rice, L.B. Antifungal agents: Mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W. Echinocandin antifungal drugs. Lancet 2003, 362, 1142–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, R.S.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Regulatory circuitry governing fungal development, drug resistance, and disease. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 213–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasqualotto, A.C.; Denning, D.W. New and emerging treatments for fungal infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 61 (Suppl. 1), i19–i30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.K.; Garzan, A.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Novel alkylated azoles as potent antifungals. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 133, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamban Chandrika, N.; Shrestha, S.K.; Ranjan, N.; Sharma, A.; Arya, D.P.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. New application of neomycin B-bisbenzimidazole hybrids as antifungal agents. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamban Chandrika, N.; Shrestha, S.K.; Ngo, H.X.; Tsodikov, O.V.; Howard, K.C.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Alkylated piperazines and piperazine-azole hybrids as antifungal agents. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamban Chandrika, N.; Shrestha, S.K.; Ngo, H.X.; Howard, K.C.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Novel fluconazole derivatives with promising antifungal activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbrook, S.Y.L.; Garzan, A.; Dennis, E.K.; Shrestha, S.K.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Repurposing antipsychotic drugs into antifungal agents: Synergistic combinations of azoles and bromperidol derivatives in the treatment of various fungal infections. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 139, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, H.X.; Shrestha, S.K.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Identification of ebsulfur analogues with broad-spectrum antifungal activity. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.K.; Fosso, M.Y.; Green, K.D.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Amphiphilic tobramycin analogues as antibacterial and antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4861–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, K.; Wang, H.; Tor, Y. Enhanced RNA binding of dimerized aminoglycosides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyffeler, P.T.; Liang, C.H.; Koeller, K.M.; Wong, C.H. The chemistry of amine-azide interconversion: Catalytic diazotransfer and regioselective azide reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 10773–10778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, T.J.; Groll, A.; Hiemenz, J.; Fleming, R.; Roilides, E.; Anaissie, E. Infections due to emerging and uncommon medically important fungal pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10 (Suppl. 1), 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: A persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullo, A. Invasive fungal infections: The challenge continues. Drugs 2009, 69 (Suppl. 1), 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero Van Dyke, M.C.; Wormley, F.L., Jr. A call to arms: Quest for a cryptococcal vaccine. Trends Microbiol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makovitzki, A.; Avrahami, D.; Shai, Y. Ultrashort antibacterial and antifungal lipopeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15997–16002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pina-Vaz, C.; Sansonetty, F.; Rodrigues, A.G.; Costa-Oliveira, S.; Tavares, C.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J. Cytometric approach for a rapid evaluation of susceptibility of Candida strains to antifungals. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2001, 7, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Reference method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts—Approved Standard; CLSI Document M27-A3; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi, 2nd ed.; CLSI Document M38-A2; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Klepser, M.E.; Malone, D.; Lewis, R.E.; Ernst, E.J.; Pfaller, M.A. Evaluation of voriconazole pharmacodynamics using time-kill methodology. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1917–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocampo, A.; Barrientos, A. Quick and reliable assessment of chronological life span in yeast cell populations by flow cytometry. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2011, 132, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 3, 4, 7a, 7b, 9, and 16 are available from the authors. |

| Yeast Strains | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| TOB | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 |

| 3 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 15.6 |

| 4 | 15.6 | 31.3 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 |

| 7a | 31.3 | 31.3 | 62.5 | 62.6 | 31.3 | 62.5 | 62.5 |

| 7b | 3.9 | 3.9 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 |

| 9 | 31.3 | 15.6 | 31.3 | 62.5 | 31.3 | 31.3 | 31.3 |

| 16 | 62.5 | 62.5 | >62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 |

| CAS | 0.975 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.48 |

| Yeast Strains | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-albicans Candida | Cryptococcus neoformans | |||||||||||

| Cpd # | CG1 | CG2 | CG3 | H | I | J | CP1 | CP2 | CP3 | CN1 | CN2 | CN3 |

| TOB | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 |

| 3 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 7.8 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 15.6 | 0.975 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| 4 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 7.8 | 1.95 | 0.48 | 0.975 |

| 7a | 31.3 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 62.5 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 31.3 | 0.975 | 0.975 | 0.48 |

| 7b | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 7.8 | 3.9 | 1.95 | 3.9 | 1.95 | 7.8 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.975 |

| 9 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 31.3 | 15.6 | 7.8 | 31.3 | 15.6 | 31.3 | 0.975 | 0.975 | 0.975 |

| 16 | >62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 31.3 | 31.3 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 1.95 | 0.975 | 3.9 |

| CAS | 1.95 | 0.24 | 0.975 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 1.95 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 15.6 | 31.3 | 15.6 |

| Filamentous Strains | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd # | K | L | M |

| TOB | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 |

| 3 | 15.6 | 3.9 | >62.5 |

| 4 | 31.3 | 3.9 | 62.5 |

| 7a | 31.3 | 3.9 | >62.5 |

| 7b | 7.8 | 1.95 | 62.5 |

| 9 | 31.3 | 3.9 | >62.5 |

| 16 | >62.5 | 3.9 | >62.5 |

| CAS | >31.3 | >31.3 | >31.3 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fosso, M.Y.; Shrestha, S.K.; Thamban Chandrika, N.; Dennis, E.K.; Green, K.D.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Differential Effects of Linkers on the Activity of Amphiphilic Tobramycin Antifungals. Molecules 2018, 23, 899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23040899

Fosso MY, Shrestha SK, Thamban Chandrika N, Dennis EK, Green KD, Garneau-Tsodikova S. Differential Effects of Linkers on the Activity of Amphiphilic Tobramycin Antifungals. Molecules. 2018; 23(4):899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23040899

Chicago/Turabian StyleFosso, Marina Y., Sanjib K. Shrestha, Nishad Thamban Chandrika, Emily K. Dennis, Keith D. Green, and Sylvie Garneau-Tsodikova. 2018. "Differential Effects of Linkers on the Activity of Amphiphilic Tobramycin Antifungals" Molecules 23, no. 4: 899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23040899

APA StyleFosso, M. Y., Shrestha, S. K., Thamban Chandrika, N., Dennis, E. K., Green, K. D., & Garneau-Tsodikova, S. (2018). Differential Effects of Linkers on the Activity of Amphiphilic Tobramycin Antifungals. Molecules, 23(4), 899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23040899