Abstract

Propargylic amines are important multifunctional building blocks that are frequently exploited in the synthesis of privileged heterocyclic entities. Herein we report on a novel flow process that achieves the safe and effective on-demand synthesis of propargylic amines in a telescoped manner. This process minimizes exposure to hazardous azide intermediates and renders a streamlined route into these building blocks. The value of this approach is demonstrated by the rapid generation of a small selection of drug-like thiazolines that result from a high-yielding reaction cascade between propargylic amines with different aryl isothiocyanates.

1. Introduction

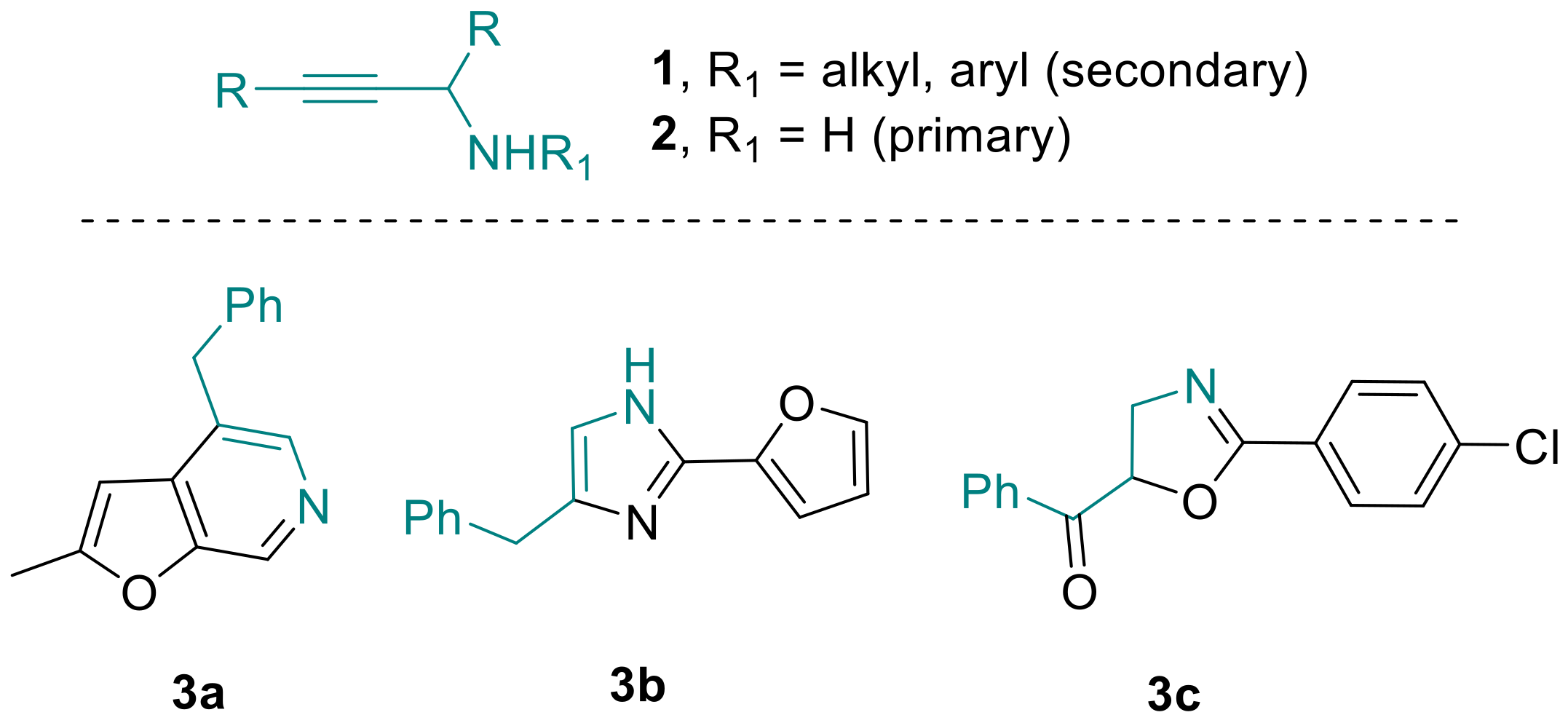

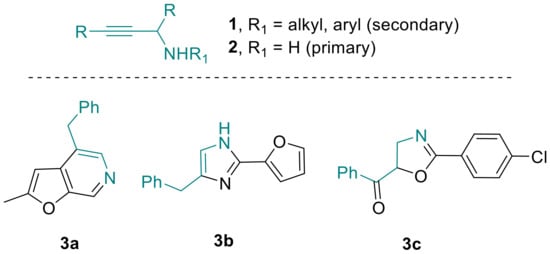

As modern drug development programs continue to rely on suitably functionalized molecular building blocks, efforts towards their effective preparation remain a challenge at the forefront of modern synthetic chemistry. Oftentimes however, such key building blocks may not be readily available or cannot be stored for long periods of time due to unavoidable degradation, making on-demand synthesis the only option for synthetic chemists. Propargylic amines [1] represent such a distinct class of important building blocks that are invaluable for accessing various nitrogen-containing entities with widespread applications in the synthesis of bioactive structures. As a consequence, propargylic amines have recently featured prominently as key components in contemporary syntheses of pyridines [2], imidazoles [3] and oxazolines [4] (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Propargylic amines and derived heterocycles.

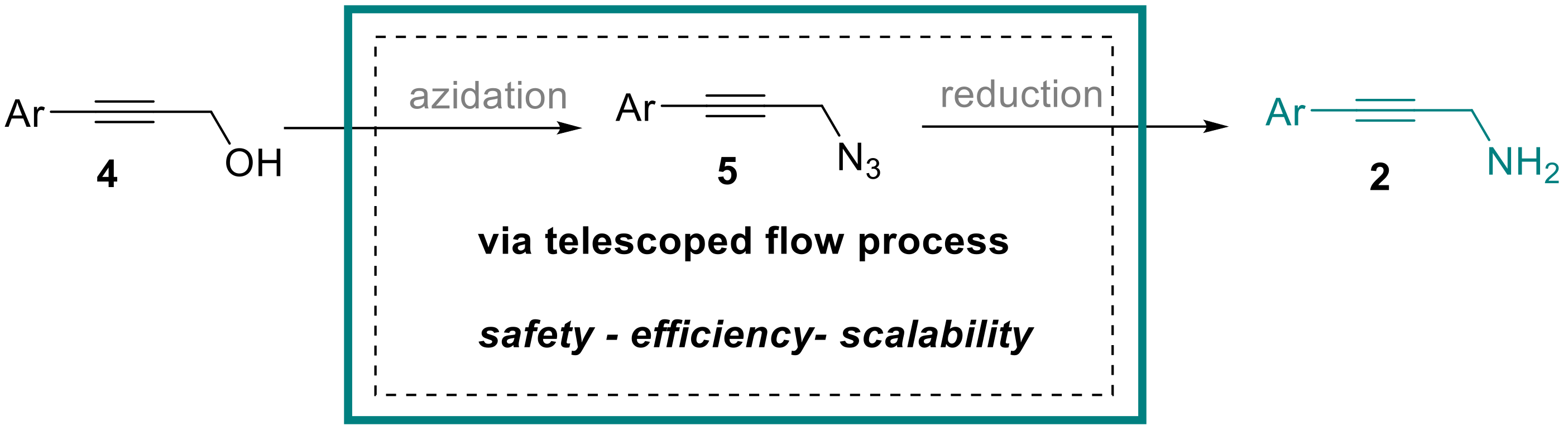

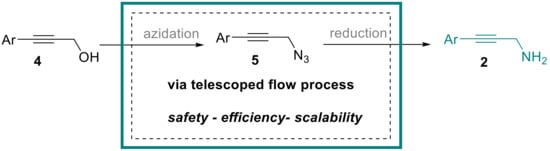

Amongst the synthetic methods available for preparing secondary propargylic amines 1, the classical metal-catalyzed three-component reaction between amines, alkynes and aldehydes stands out as the most widely utilized protocol [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Further options include the amination of allenes [11], the decarboxylative coupling of amines with alkyne carboxylic acids in the presence of formaldehyde [12], the copper-catalyzed coupling of aryl boronic acids with ammonia and propargylic halides [13] or the rhenium-catalyzed direct substitution of activated propargylic alcohols [14]. In contrast, the synthesis of primary propargylic amines 2 typically requires a stepwise and therefore more cumbersome approach that cannot be performed in a single-pot fashion. Therefore, the stepwise conversion of propargylic alcohols 4 via the activation and subsequent displacement of the hydroxy group with a suitable nitrogen nucleophile is typically required. Commonly, azide is the preferred nucleophile that subsequently must be converted into the desired amine functionality by suitable reduction processes (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Telescoped flow approach to propargylic amines 2.

To support an ongoing synthesis program, we required a robust and scalable route towards a variety of different propargylic amines 2 bearing different aryl-substituents. In view of potential safety concerns that might manifest during reaction scale-up, we opted to develop a continuous flow protocol that would not only enable and streamline the assembly and delivery of these entities, but also mitigate any safety concerns associated with the introduction and subsequent reduction of the azide functionality. The latter is commonly accomplished under Staudinger reduction conditions releasing stoichiometric amounts of nitrogen gas in the process. Thus, we aimed at developing a telescoped process that would allow performing these two steps in a continuous flow reactor [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] to conveniently and safely [23] deliver a small selection of these propargylic amines on multi-gram scale.

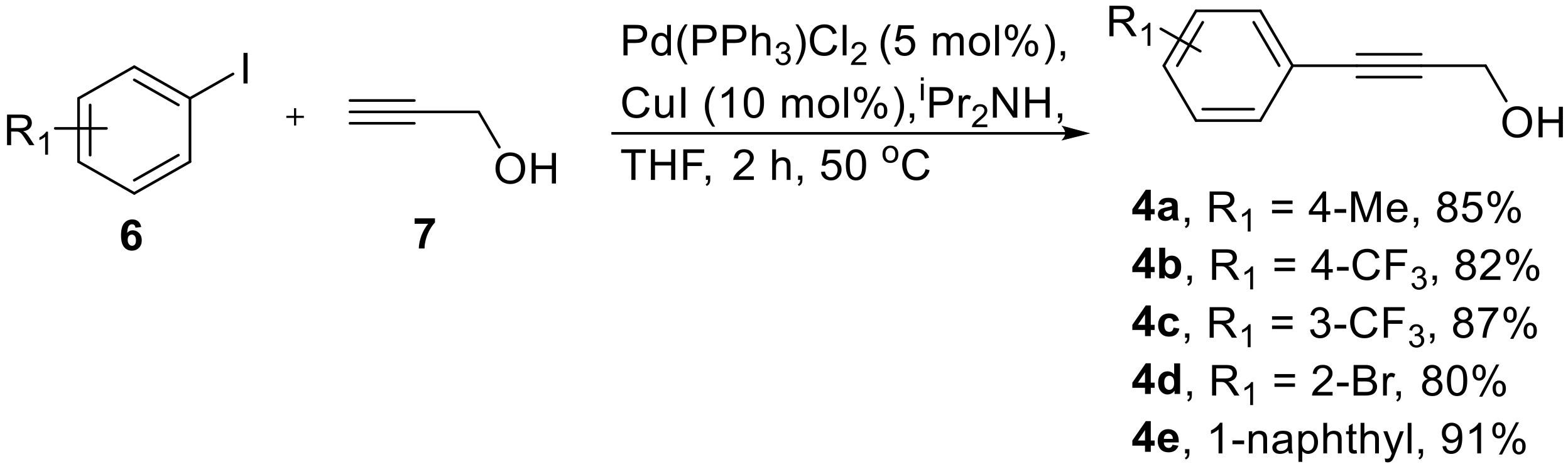

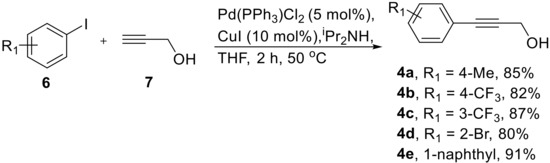

2. Results

As outlined in Scheme 2, propargylic alcohols were identified as suitable starting materials for the telescoped flow synthesis of the corresponding amine structures. The synthesis of a small selection of propargylic alcohols 4a–e was readily accomplished in batch mode using typical Sonogashira coupling conditions between aryl iodides 6 and propargyl alcohol (7) giving gram quantities of the desired entities (Scheme 3). As no difference was noted between performing this reaction at small (1 mmol) or larger scale (20 mmol), no further optimization was required.

Scheme 3.

Sonogashira reaction yielding propargylic alcohols 4.

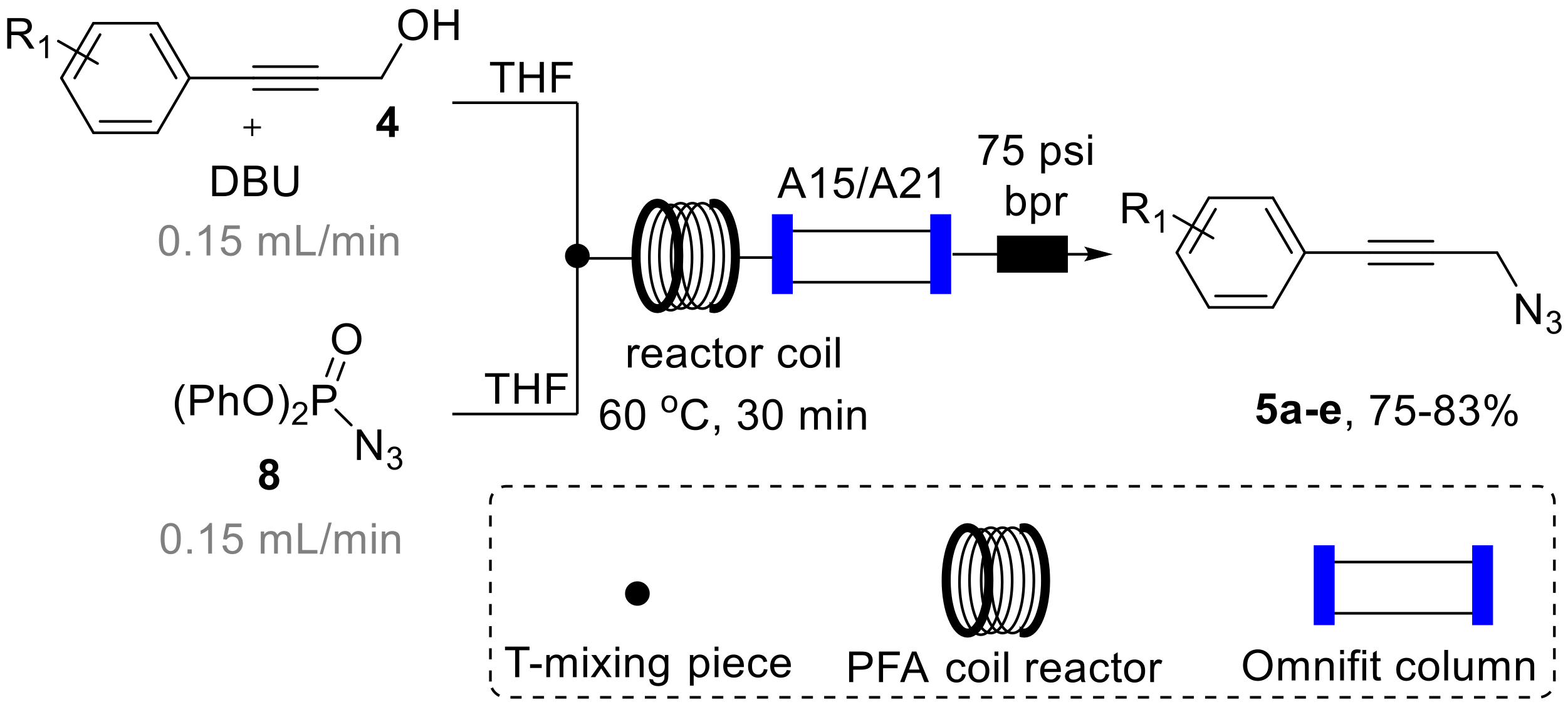

Having established a rapid entry into the desired substrates 4, we turned our attention to their conversion into the propargylic amine targets in flow mode. As mentioned earlier, this was driven by the desire to streamline the synthesis effort avoiding time consuming isolation and purification stages for the potentially hazardous azide intermediate 5 as well as the release of nitrogen gas during the Staudinger reduction step, that could lead to a dangerous run-away process. To accomplish this, we opted to utilize diphenylphosphoryl azide (8, DPPA) as a readily available and bench stable azide donor that we [24] and others [25,26] had exploited previously in flow-based azide transformations. This rendered the opportunity to subsequently treat the resulting propargylic azide with triphenylphosphine in a suitable solvent system to affect the formation of the desired propargylic amines via a telescoped Staudinger reduction [27] sequence (Scheme 4).

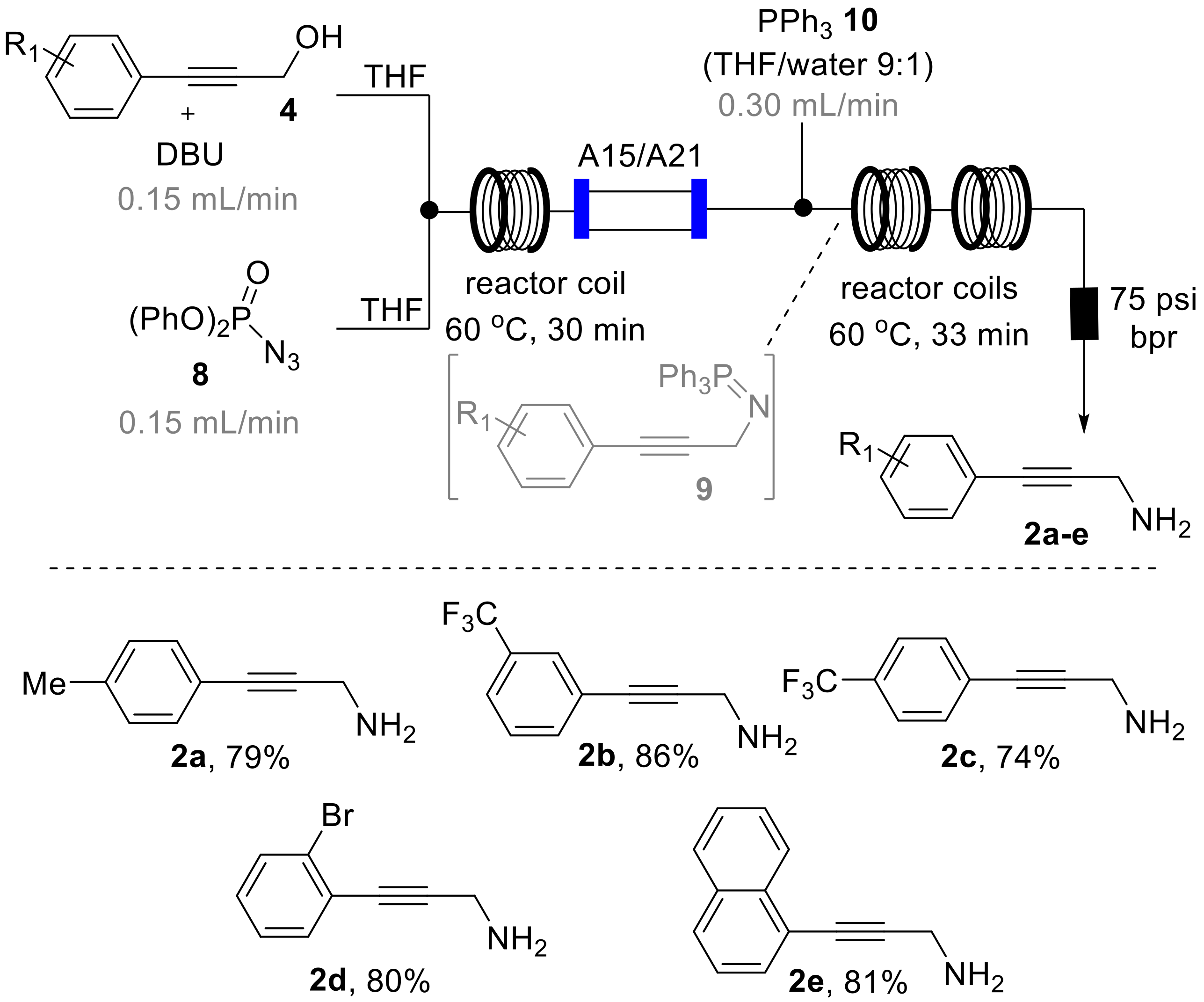

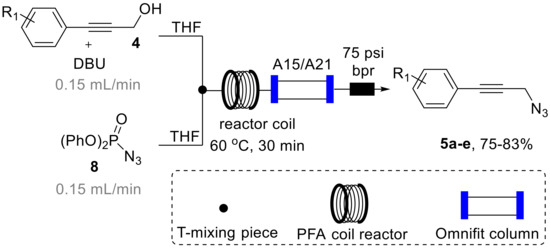

Scheme 4.

Azidation of 4 using DPPA (8) in continuous flow mode.

As depicted in Scheme 4, we designed a flow process utilizing a Vapourtec R-series system that combines a solution of DPPA (8, THF, 2 M, 2 equiv., stream A) via a T-piece with a second stream containing the substrate (4, THF, 1 M, 1 equiv.) and DBU (1.3 equiv.) as a base that we had found to efficiently promote this transformation. The resulting mixture was then directed into a heated flow coil reactor (10 mL, PFA, 1/16′ i.d.) and collected after passing a back-pressure regulator (75 psi).

During an initial optimization study 1H-NMR analysis of the resulting reaction mixture revealed that elevated temperature (60 °C) in combination with residence times of 30 min were optimal to reach full conversion of 4 to the desired azide products 5 that are isolable entities. It was furthermore found that using an excess of DPPA (2 equiv.) was required to reliably achieve this transformation in a short period of time. Using these conditions allowed to generate the desired azide products (5a–c) in good isolated yields also permitting their full spectroscopic characterization (see Supplementary Materials for full details). Furthermore, on small scale (1 mmol) this flow process was successfully coupled with in-line scavenging of by-products and spent reagents by placing a mixed bed of sulfonic acid resin (Amberlyst A15) and an immobilized tertiary amine base (Amberlyst A21) in an Omnifit glass column (15 cm length, 1 cm i.d., containing ~3 equiv. of each species) to yield a mixture of the desired azide product and residual DPPA that could either be purified using column chromatography or directed into the subsequent Staudinger reduction process (vide infra) [28].

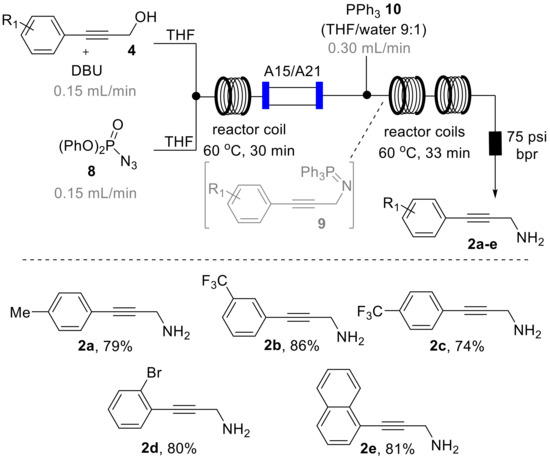

Subsequent batch test reactions for the desired Staudinger reduction of intermediates 5 had indicated that the transient iminophosphorane species 9 along with nitrogen gas is readily formed upon treatment of the azide intermediate with triphenylphosphine (10, 1.3 equiv. in THF). Furthermore, the hydrolysis of the iminophosphorane turned out to be a facile process yielding the desired propargylic amines upon addition of water (10% by volume) to this reaction mixture.

To translate these preliminary results into a telescoped flow process, we expanded on the original set-up by mixing the azide stream with a solution of triphenylphosphine (90:10 THF/water, 2.0 equiv., Scheme 5). To match the effective concentration of the azide intermediate 5 in the initial reaction stream and mitigate any dispersion-related problems a slight excess of the triphenylphosphine reagent (1.5 equiv.) was used [29]. The resulting reaction mixture was directed through two additional flow coils (PFA, 10 mL volume each) maintained at 60 °C (residence time: 33 min) before passing a back-pressure regulator (75 psi) and collection in a flask. Due to the continuous process and the related generation and removal of nitrogen gas as a by-product, no build-up of pressure was noted as this gaseous by-product was steadily removed in the course of the reaction. This highlights how flow processing circumvents the need for additional safety and process control measures and allows for directly scaling this sequence without recourse for further adaptations. At this stage the desired amine products 2a–e were isolated after extractive acid-base work-up in good yields and excellent purity as listed in Scheme 5.

Scheme 5.

Telescoped azide formation and Staudinger reduction sequence in flow mode.

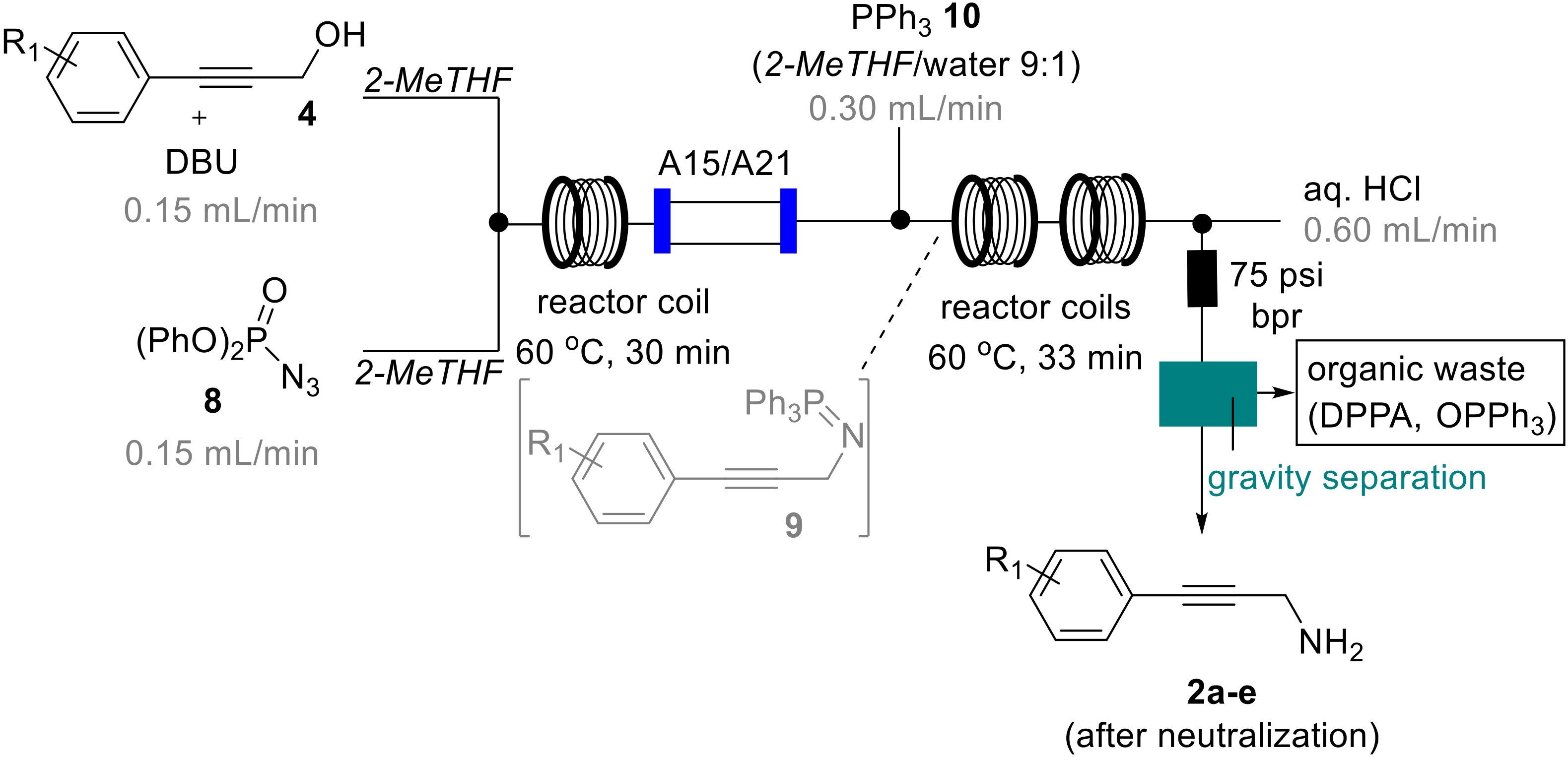

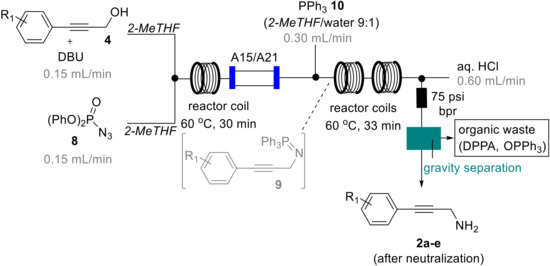

To further expand on this telescoped process and in view of effectively separating the desired amine product from residual DPPA, we opted to incorporate the acid-base extraction process within the flow sequence. This also addresses safety concerns regarding the co-isolation of larger quantities of unreacted DPPA when transitioning from small (1 mmol) to larger scale (5 to >10 mmol) operations. To this end an additional HPLC pump was used to deliver a stream of aqueous acid (HCl, 1 M, 0.6 mL/min) that was mixed via a T-piece with the crude mixture from the azidation/Staudinger reduction sequence.

After collection of the resulting biphasic mixture in a separating funnel, the desired propargylic amine products were again obtained in pure form upon neutralization and back-extraction into either DCM or EtOAc. Although the mixing in a conventional T-piece aided in emulsifying and consequently protonating the propargylic amine species, it was found that THF as reaction solvent led to slow phase separation and thus potential loss of product (around 10–15%). A quick reevaluation of suitable solvent alternatives revealed that 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) could effectively replace THF as it resulted in faster phase separation. Additionally, this solvent swap would be attractive as 2-MeTHF is reportedly more stable towards acids, whilst being both bioderived and biodegradable [30,31,32]. The final flow process (Scheme 6) thus used 2-MeTHF as sole organic solvent and allowed the effective generation of the desired propargylic amines as well as in-line separation from by-products and excess azide donor (DPPA).

Scheme 6.

Final telescoped flow process using 2-MeTHF.

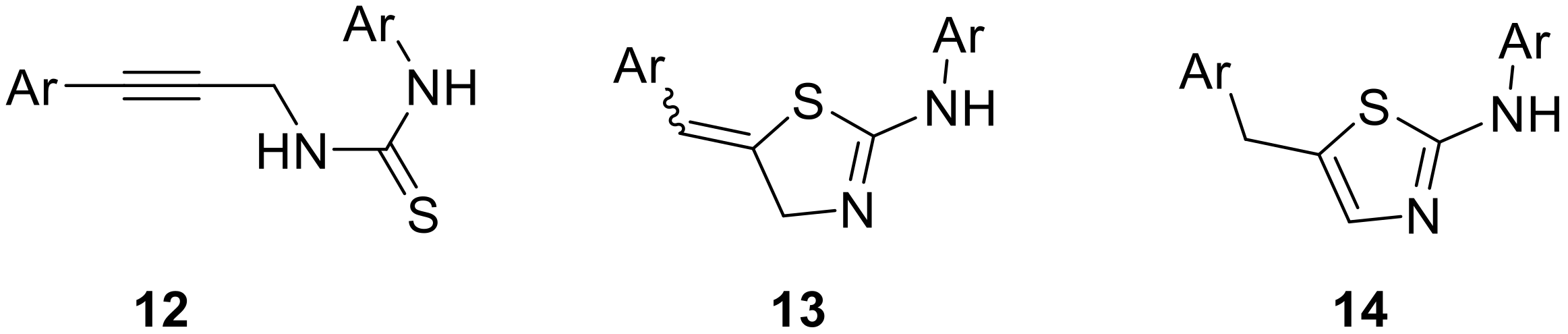

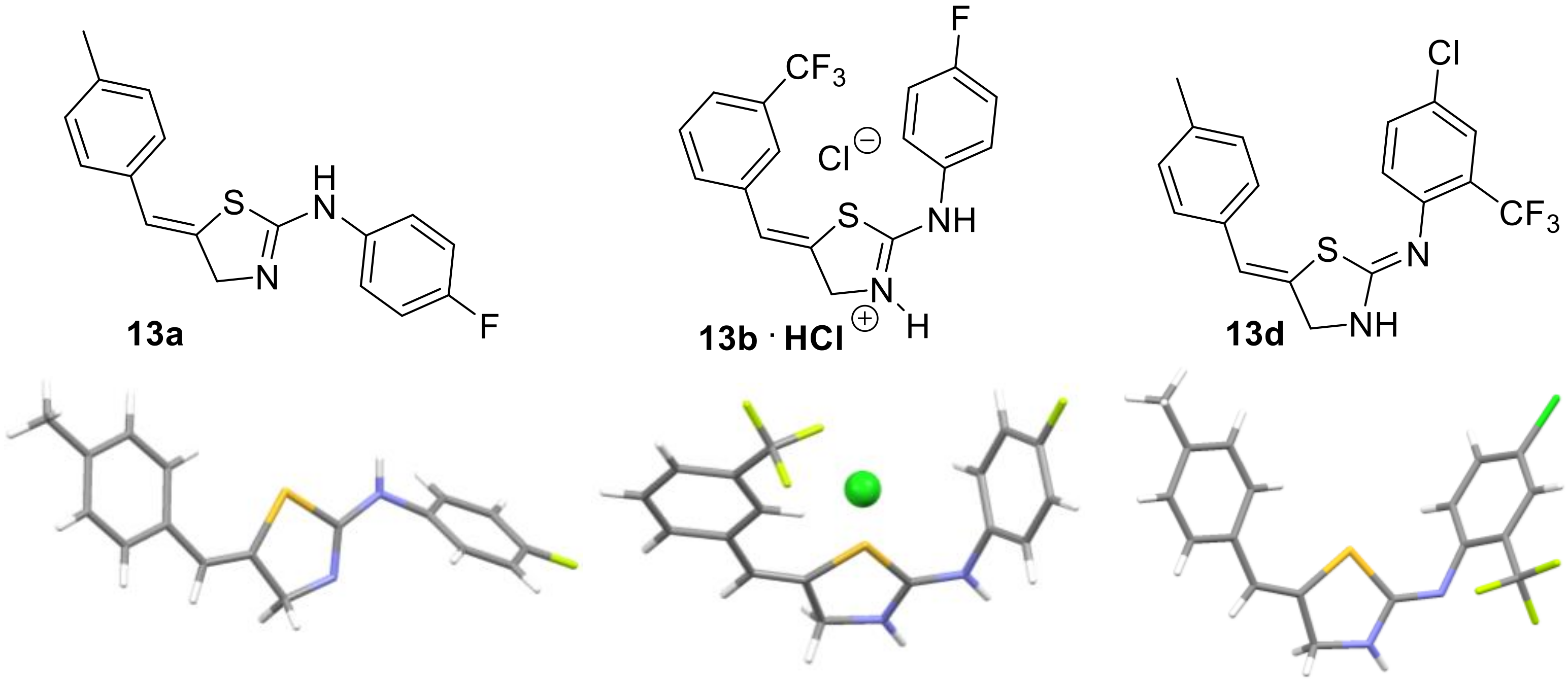

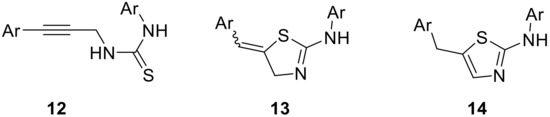

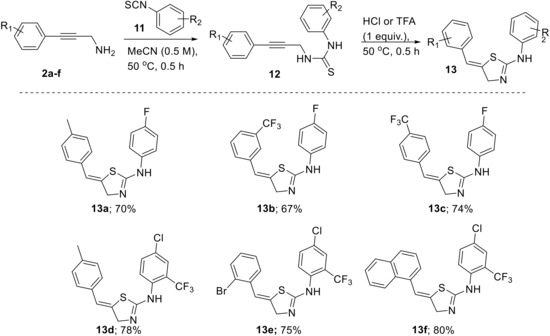

To exploit our effective route into different aryl-propargyl amines and demonstrate the value of the flow process developed to generate these materials on-demand, we studied their reaction with different isothiocyanates 11. Such a process was expected to yield valuable heterocyclic derivatives via intermediate thiourea adducts 12 that would cyclize in an acid-catalyzed reaction cascade. This sequence is interesting as it allows direct access to either thiazoline or thiazole derivatives 13 or 14 as reported in the literature [33,34,35,36,37]. We were specifically interested in selectively generating thiazoline species as these provide an exocyclic alkene that can serve as a handle for accessing highly functionalized derivatives (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of thiazolines 13 and thiazoles 14 derived from propargylic thioureas 12.

To this end we treated a solution of the respective propargylic amine 2 (0.5 M, MeCN) with stoichiometric amounts of suitable aryl isothiocyanates (11). The expected thiourea intermediate 12 formed within 30 min and upon addition of acid (HCl or TFA, 1.0 equiv.) smoothly converted into the heterocyclic target structures within a short time (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

Cyclization cascade towards thiazoline products 13.

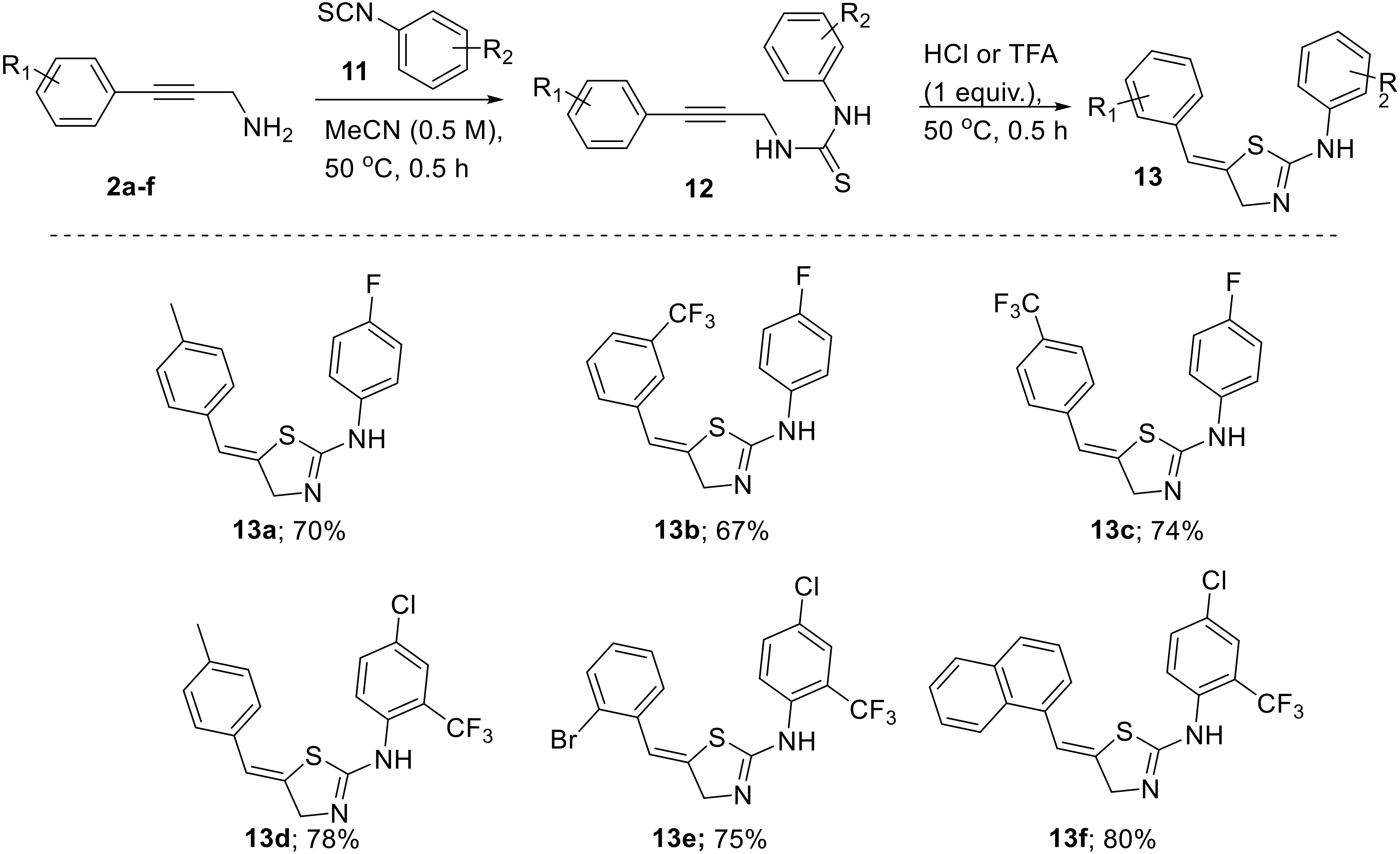

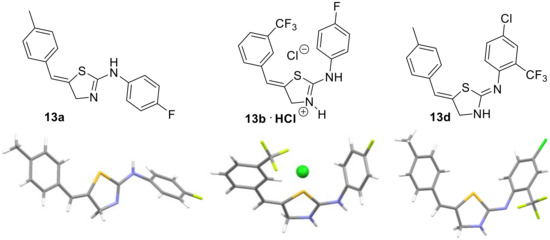

Encouraged by these results we opted to verify the provisional structural assignment of our products as being thiazolines bearing an exocyclic alkene. This was warranted as conventional spectroscopic techniques were not allowing for an unambiguous assignment and literature precedent was not clear. We thus used single crystal diffraction experiments to prove that the expected thiazolines had indeed formed. Importantly, this allowed to demonstrate that thiazoline products were obtained in all cases independent whether a base was employed during the work-up as summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystallographic study on selected thiazolines.

These results furthermore confirm the Z-configuration of the alkene and demonstrate that the thiazoline tautomer is favored over the aromatic thiazole structure, highlighting the relevance of an extended π-conjugated system over the aromaticity of the alternative thiazole heterocycle.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

Unless otherwise stated, all solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific and used without further purification. Substrates and reagents were purchased from Fluorochem or Sigma Aldrich and used as received.

1H-NMR spectra were recorded on 300 or 400 MHz instruments and are reported relative to residual solvent: CHCl3 (δ 7.26 ppm). 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on the same instruments (100 MHz) and are reported relative to CHCl3 (δ 77.16 ppm). Data for 1H-NMR are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ/ppm) (integration, multiplicity, coupling constant (Hz)). Multiplicities are reported as follows: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = pentet, m = multiplet, br. s = broad singlet, app = apparent. Data for 13C-NMR are reported in terms of chemical shift (δ/ppm) and multiplicity (C, CH, CH2 or CH3). DEPT-135, COSY, HSQC, HMBC and NOESY experiments were used in the structural assignment. IR spectra were obtained by use of a Platinum spectrometer (neat, ATR sampling, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) with the intensities of the characteristic signals and are reported as weak (w, <20% of tallest signal), medium (m, 21–70% of tallest signal) or strong (s, >71% of tallest signal). High-resolution mass spectrometry was performed using the indicated techniques on a Micromass LCT orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, UK with leucine-enkephalin (Tyr-Gly-Phe-Leu) as an internal lock mass. Continuous flow experiments were performed on a Vapourtec E-series system (Vapourtec, Bury Saint Edmunds, UK) in conjunction with Omnifit glass columns.

3.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Propargyl Alcohols 4a–e

To a solution of aryl iodide (10 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) in THF (10 mL, 1.0 M) was added 2-propyn-1-ol (1.24 mL, 1.2 equiv.), diisopropylamine (1.68 mL, 1.2 equiv.), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.3 mmol, 3 mol%) and CuI (0.5 mmol, 5 mol%). The resulting solution changed colour from yellow to orange and finally brown in two minutes. The reaction mixture was heated at 50 °C and stirred until complete consumption of the aryl iodide was observed (tlc, 2 h). After filtering the crude material over a pad of silica (5 g) and evaporation of the solvent the crude material (1H-NMR) was purified by silica column chromatography (eluent 10% EtOAc in pentanes, Rf = 0.41). After removal of the volatiles, the desired hydroxyl product was typically isolated as yellow oil with a purity > 98% (by 1H-NMR) and was used directly in the next step. Copies of NMR spectra are provided in the electronic Supplementary Materials.

3.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Propargyl Azides 5a–e

A flow set-up was constructed in which a first stream containing DPPA (2 M, THF, 2 equiv.) was mixed with a stream containing the substrate (4a–e, 1 M, THF, 1 equiv.) and DBU (1.3 equiv.). Each stream was pumped at a flow rate of 0.15 mL/min and blended in a T-piece. The resulting mixture was passed into a tubular flow coil (10 mL, PFA, 60 °C, ~30 min residence time) to affect the azidation reaction. The exiting stream was directed through an Omnifit glass column (10 cm x 1.0 cm i.d., ambient temperature) containing a mixture of washed scavenger resins (A21 and A15, ~1:1 ratio, 3 equiv. each) to remove acidic and basic by-products. After passing a back-pressure regulator (75 psi) the product was collected in a flask. Purification was achieved by silica column chromatography (2–5% EtOAc/hexanes) giving the desired products typically as oils.

3.4. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Propargyl Amines 2a–e

To realise the Staudinger reduction step in a telescoped flow process, the purified stream of the intermediate azide solution (see above) was combined in a T-piece with a stream of triphenylphosphine (2 equiv.) in aqueous THF (THF/water, 9:1) at equal flow rates of 0.3 mL/min. The resulting mixture then entered two consecutive flow coils (PFA, 10 mL each, 60 °C, residence time ~33 min) before passing a back-pressure regulator (75 psi) and collection in a flask. After evaporation of the volatiles, the crude mixture was partitioned between DCM (2 × 25 mL) and aqueous HCl (1 M). After discarding the organic phase, the pH of the aqueous layer was adjusted to 8–9 and the mixture was extracted with DCM (2 × 25 mL). The combined organic extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered and evaporated in vacuo giving the desired products either as oils or amorphous solids.

3.5. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Thiazolines 13a–e

To a solution of the amine 2a–e (1 equiv.) in MeCN (0.5 M) was added a stoichiometric amount of aryl isothiocyanate. The resulting mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 30 min before addition of acid (TFA or HCl, 1 equiv.). Once complete consumption of substrates to a new product was observed by tlc (0.5-1 h), the pH was adjusted to 7 by addition of Na2CO3 (sat. aqueous). After evaporation of volatiles under reduced pressure, the crude material was triturated from mixtures of MeCN and water (4:1). Alternatively, silica column chromatography (5–20% EtOAc/hexanes was used to obtain pure thiazoline products as amorphous solids that can be recrystallized to grow single crystals (MeOH/DCM).

3-(p-Tolyl)prop-2-yn-1-ol (4a): Yield: 85% (1.2 g; 8.3 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.33 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 4.48 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 1.72 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.7 (C), 131.6 (2CH), 129.1 (2CH), 119.4 (C), 86.5 (C), 85.7 (C), 51.7 (CH2), 21.5 (CH3). IR (neat, cm−1) 3296 (m), 2919 (m), 2863 (m), 2237 (s), 1651 (w), 1607 (w), 1562 (w), 1509 (s), 1407 (m), 1379 (m), 1260 (m), 1026 (s), 816 (s). Rf = 0.41 (10% EtOAc in pentanes). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H10O 146.0732, found 146.0716 (Δ = −4.1 ppm).

3-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)prop-2-yn-1-ol (4b): Yield: 82% (1.4 g; 7.0 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.55 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.51 (s, 2H), 2.16 (s, H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 131.9 (2CH), 130.1 (q, J = 30.5 Hz, C), 126.3 (br s, C), 125.5 (q, J = 4.0 Hz, 2CH), 123.8 (q, J = 273 Hz, CF3), 89.6 (C), 84.3 (C), 51.4 (CH2). 19F-NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −62.9. Rf = 0.44 (10% EtOAc in pentanes). IR (neat, cm−1) 3256 (m), 2920 (w), 2863 (w), 2242 (w), 1929 (w),1803 (w), 1685 (w), 1614 (m), 1567 (w), 1481 (w),1403 (w), 1316 (s), 1170 (s), 1119 (s), 1104 (s), 1015 (s), 952 (m), 841 (s), 710 (m), 598 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H7F3O 200.0449, found 200.0445 (Δ = −2.0 ppm).

3-(3-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)prop-2-yn-1-ol (4c): Yield: 87% (1.6 g; 8.2 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.68 (s, 1H), 7.57 (t, J = 12.6 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 2H), 2.25 (s, 1H).13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 134.7 (m, CH), 130.9 (q, J = 32.5 Hz, CH), 128.8 (CH), 128.4 (q, J = 4.0 Hz, C), 125.0 (q, J = 4.0 Hz, CH), 123.6 (q, J = 274.1 Hz, CF3) 123.5 (C), 88.8 (C), 84.1 (C), 51.4 (CH2). 19F-NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −63.1. Rf = 0.43 (10% EtOAc in pentanes). IR (neat, cm−1) 3297 (m), 2917 (s), 2868 (s), 2112 (s), 1611 (w), 1588 (w), 1486 (m), 1433 (m), 1331 (s), 1237 (s), 1125 (s), 1029 (m), 973 (m), 902 (m), 802 (s), 696 (s). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H7F3O 200.0449, found 200.0453 (Δ = 2.0 ppm).

3-(2-Bromophenyl)prop-2-yn-1-ol (4d): Yield: 80% (0.84 g, 4.0 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.57 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (td, J = 7.7, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (td, J = 7.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.55 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 1.78 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.5 (CH), 132.4 (CH), 129.7 (CH), 127.0 (CH), 125.4 (C), 124.7 (C), 91.8 (C), 84.2 (C), 51.7 (CH2). IR (neat, cm−1) 3303 (broad), 2913 (w), 1587 (w), 1468 (s), 1433 (m), 1052 (m), 1023 (s), 953 (m), 749 (s), 653 (m), 574 (m).

3-(Naphthalen-1-yl)prop-2-yn-1-ol (4e): Yield: 91% (0.83 g, 4.6 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.36 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.87–7.80 (m, 2H), 7.71 – 7.67 (m, 1H), 7.58 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.49 (m, 1H), 7.43–7.38 (m, 1H), 4.67 (s, 2H), 2.45 (s, 1H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.3 (C), 133.1 (C), 130.7 (CH), 129.0 (CH), 128.3 (CH), 126.8 (CH), 126.4 (CH), 126.1 (CH), 125.2 (CH), 120.2 (C), 92.2 (C), 83.8 (C), 51.8 (CH2). IR (neat, cm−1) 3040 (w), 2933 (w), 2170 (w), 2121 (m), 1643 (s), 1589 (s), 1487 (s), 1249 (s), 1205 (s), 1161 (m), 1090 (s), 961 (m), 896 (s), 771 (s), 680 (s), 528 (s). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C13H9 (M-CH2OH) 165.0704, found 165.0706 (Δ = 1.1 ppm).

1-(3-Azidoprop-1-yn-1-yl)-4-methylbenzene (5a): Yield: 75% (0.8 g; 4.7 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.36 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.13 (s, 2H), 2.36 (s, 3H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.0 (C), 131.8 (2CH), 129.1 (2CH), 118.9 (C), 87.6 (C), 80.3 (C), 40.6 (CH2), 21.5 (CH3). Rf = 0.80 (5% EtOAc in pentanes). IR (neat, cm−1) 3029 (w), 2920 (w), 2860 (w), 2217 (w), 2116 (s), 1607 (w), 1509 (s), 1442 (m), 1338 (m), 1267 (m), 1238 (s), 865 (m), 867 (s), 732 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H9N (M-N2) 143.0735, found 143.0739 (Δ = 2.8 ppm).

1-(3-Azidoprop-1-yn-1-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzene (5b): Yield: 83% (0.8 g; 3.6 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.73 (s, H), 7.63 (t, J = 10.9 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, H), 4.17 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 135.0 (CH), 131.0 (q, J = 34 Hz, C), 128.9 (CH), 128.6 (q, J = 4 Hz, CH), 125.4 (q, J = 4 Hz, CH), 123.6 (q, J = 272 Hz, CF3),122.9 (C), 85.4 (C), 82.8 (C), 40.4 (CH2). 19F-NMR (282 MHz, CDCl3) δ −63.0. Rf = 0.78 (5% EtOAc in pentanes). IR (neat, cm−1) 3080 (w), 2940 (w), 2105 (s), 1635 (s), 1590 (s), 1486 (m), 1434 (m), 1331 (s), 1237 (m), 1167 (s), 1127 (s), 1095 (m), 1747 (m), 1005 (m), 903 (m), 803 (s), 695 (s), 656 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H6F3N (M-N2)197.0452, found 197.0450 (Δ = −1.0 ppm).

1-(3-Azidoprop-1-yn-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzene (5c): Yield: 77% (0.7 g; 3.1 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.55-7.60 (m, 4H), 4.16 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100MHz, CDCl3) δ 132.1 (2CH), 130.6 (q, J = 33 Hz, C), 125.7 (br s, C) 125.3 (q, J = 4 Hz, 2CH), 125.8 (q, J = 272 Hz, CF3), 85.9 (C), 83.6 (C), 40.4 (CH2). 19F-NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −63.0. Rf = 0.78 (5% EtOAc in pentanes). IR (neat, cm−1) 2916 (w), 2115 (s), 1922 (s), 1570 (m), 1406 (m), 1321 (s), 1269 (m), 1241 (m), 1166 (m), 1126 (s), 1106 (m), 1068 (s), 1018 (m), 842 (s), 688 (s), 554 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H6F3N (M-N2) 197.0452, found 197.0458 (Δ = 3.0 ppm).

1-(3-Azidoprop-1-yn-1-yl)-2-bromobenzene (5d): Yield: 82% (0.7 g; 2.9 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.59 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.20 (td, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 4.19 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.8 (CH), 132.5 (CH), 130.0 (CH), 127.0 (CH), 125.4 (C), 124.2 (C), 85.8 (C), 85.6 (C), 40.6 (CH2). IR (neat, cm−1) 2910 (w), 2119 (s), 2100 (s), 1469 (s), 1434 (m), 1335 (m), 1246 (m), 1233 (m), 1052 (m), 1026 (m), 988 (m), 865 (m), 750 (s), 688 (m), 650 (m), 552 (m), 512 (m), 445 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C9H6Br (M-N3) 192.9653, found 192.9657 (Δ = 2.1 ppm).

1-(3-Azidoprop-1-yn-1-yl)naphthalene (5e): Yield: 79% (0.67 g; 3.2 mmol). Appearance: pale yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.33 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.89–7.85 (m, 2H), 7.73 (dd, J = 7.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.51 (m, 1H), 7.44 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.1 (C), 133.1 (C), 131.1 (CH), 129.4 (CH), 128.3 (CH), 127.0 (CH), 126.5 (CH), 125.9 (CH), 125.1 (CH), 119.6 (C), 85.8 (C), 85.4 (C), 40.9 (CH2). IR (neat, cm−1) 3058 (w), 2119 (s), 2094 (s), 1586 (w), 1507 (w), 1395 (m), 1335 (m), 1247 (s), 865 (m), 797 (s), 770 (s).

3-(p-Tolyl)prop-2-yn-1-amine (2a): Yield: 79% (0.45 g; 3.2 mmol). Appearance: yellow solid. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.29 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 3.63 (s, 2H), 2.33 (s, 3H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.1 (C), 131.4 (2CH), 129.0 (2CH), 120.1 (C), 89.5 (C), 82.5 (C), 32.2 (CH2), 21.4 (CH3). IR (neat, cm−1) 3347 (w), 3265 (m), 3027 (w), 2916 (w), 2247 (w), 2131 (w), 1906 (s), 1607 (s), 1555 (m), 1433 (s), 1330 (s), 1306 (s), 969 (m), 813 (s), 544 (m), 495 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H12N (M + H) 146.0970, found 146.0969 (Δ = −0.5 ppm).

3-(3-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)prop-2-yn-1-amine (2b): Yield: 86% (0.5 g; 2.6 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.67 (s, 1H), 7.55 (m, 2H), 7.41 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.66 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 134.6 (m, CH), 130.9 (m, C), 128.8 (CH), 128.4 (q, J = 3 Hz, CH), 124.6 (q, J = 4 Hz, CH), 124.2 (C), 123.7 (q, J = 274 Hz, CF3), 91.8 (C), 81.0 (C), 32.1 (CH2). 19F-NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −63.0. IR (neat, cm−1) 2919 (w), 2118 (w), 1587 (w), 1486 (m), 1328 (s), 1236 (m), 1163 (m), 1123 (s), 1073 (m), 1001 (w), 902 (m), 696 (m), 658 (s). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H9NF3 (M + H) 200.0687, found 200.0683 (Δ = −2.0 ppm).

3-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)prop-2-yn-1-amine (2c): Yield: 74% (0.44 g; 3.0 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.53 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 3.66 (s, 2H), 1.47 (br s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 131.8 (2CH), 129.7 (q, J = 33 Hz, C), 127.0 (br, C), 125.2 (q, J = 4 Hz, 2CH), 123.9 (q, J = 272 Hz, CF3), 92.9 (C), 81.1 (C), 32.0 (CH2). 19F-NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −62.9. IR (neat, cm−1) 3285 (w), 2921 (w), 2851 (w), 2239 (w), 1614 (m), 1437 (s), 1321 (s), 1261 (w), 1164 (s), 1122 (s), 1005 (m), 1168 (s), 1017 (m), 967 (s), 598 (m), 577 (w). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C10H9NF3 (M + H) 200.0687, found 200.0697 (Δ = 5.0 ppm).

3-(2-Bromophenyl)prop-2-yn-1-amine (2d): Yield: 80% (0.42 g; 2.0 mmol). Appearance: yellow oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.56 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (td, J = 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (td, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (s, 2H), 1.51 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.3 (CH), 132.3 (CH), 129.2 (CH), 127.0 (CH), 125.4 (C), 125.3 (C), 81.1 (C), 32.3 (CH2); 1 C not observed. IR (neat, cm−1) 3367 (w), 2914 (w), 1586 (w), 1468 (s), 1433 (m), 1330 (m), 1067 (m), 1048 (s), 1025 (m), 967 (m), 860 (m), 749 (s), 652 (m), 524 (m), 445 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C9H9NBr (M + H) 209.9918, found 209.9924 (Δ = 2.7 ppm).

3-(Naphthalen-1-yl)prop-2-yn-1-amine (2e): Yield: 81% (0.44 g; 2.4 mmol). Appearance: colourless oil. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.33 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 0H), 7.56 (ddd, J = 8.3, 6.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (ddd, J = 8.1, 6.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.44–7.39 (m, 1H), 3.81 (s, 2H), 1.56 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.3 (C), 133.1 (C), 130.2 (CH), 128.5 (CH), 128.2 (CH), 126.6 (CH), 126.3 (CH), 126.1 (CH), 125.2 (CH), 120.8 (C), 95.2 (C), 80.5 (C), 32.5 (CH2). IR (neat, cm−1) 3368 (w), 3056 (w), 2913 (w), 1584 (m), 1506 (w), 1395 (m), 1330 (m), 948 (m), 862 (m), 797 (s), 770 (s), 566 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C13H12N (M + H) 182.0970, found 182.0969 (Δ = −0.4 ppm).

(Z)-N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(4-methylbenzylidene)-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-amine (13a): Yield: 70% (0.42 g; 1.4 mmol). Appearance: yellow solid. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ 7.44–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (t, J = 2 Hz, H), 4.95 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 2.34 (s, 3H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ 162.4 (d, J = 249 Hz, CF), 138.4 (C), 132.1 (C), 129.2 (2CH), 127.4 (2CH), 127.0 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2CH), 124.2 (C), 124.1 (CH), 116.8 (d, J = 24 Hz, 2CH), 56.0 (CH2), 19.9 (CH3), 2 carbons not observed. 19F-NMR (376 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ −113.7. IR (neat, cm−1) 3117 (w), 3048 (m), 2855 (m), 2675 (s), 1605 (s), 1555 (m), 1507 (s), 1460 (m), 1352 (s), 845 (s), 790 (m), 650 (m), 514 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C17H15FN2S (M + H) 299.1018, found 299.1008 (Δ = −3.4 ppm).

(Z)-N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(3-(trifluoromethyl)benzylidene)-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-amine (13b): Yield: 67% (0.47 g; 1.3 mmol). Appearance: colourless solid. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ 7.58–7.67 (m, 4H), 7.46–7.49 (m, 2H), 7.29 (t, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (t, J = 2.3 Hz, H), 5.02 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ 162.5 (d, J = 248 Hz, CF), 136.0 (C), 131.5 (C), 130.9 (q, J = 32 Hz, C), 130.6 (CH), 129.6 (CH), 128.3 (C), 127.0 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2CH), 124.4 (q, J = 4 Hz, CH), 124.2 (q, J = 4 Hz, CH), 123.9 (CF3, q, J = 272 Hz), 122.4 (CH), 116.8 (d, J = 24 Hz, 2CH), 56.2 (CH2); 1 C not observed. 19F-NMR (376 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ −64.4 (3F), −113.6 (1F). IR (neat, cm−1) 3390 (w), 3190 (m), 2827 (m), 2650 (m), 1629 (s), 1510 (s), 1487 (s), 1170 (s), 909 (m), 878 (s), 797 (m), 758 (m), 645 (m), 520 (w). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C17H13N2F4S (M + H) 357.0736, found 353.0737 (Δ = 0.4 ppm).

(Z)-N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(4-(trifluoromethyl)benzylidene)-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-amine (13c): Yield: 74% (0.52 g; 1.5 mmol). Appearance: colourless solid. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ 7.74 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.47–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.30 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (br s, H), 5.04 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ 161.8 (d, J = 249 Hz, C), 138.7 (C), 131.5 (C), 129.5 (q, J = 32 Hz, C), 128.9 (C), 128.0 (2CH), 127.0 (2CH), 125.5 (q, J = 4 Hz, 2CH), 124.0 (q, J = 272 Hz, CF3), 122.4 (CH), 116.8 (d, J = 23 Hz, 2CH), 56.3 (CH2); 1 C not observed. 19F-NMR (376 MHz, d4-MeOD) δ −64.2 (3F), δ −113.6 (1F). IR (neat, cm−1) 2926 (w), 2842 (m), 2704 (m), 1654 (m), 1614 (m), 1577 (m), 1506 (s), 1319 (s), 1110 (m), 832 (s), 688 (m), 646 (m), 507 (s). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C17H12F4N2S (M + H) 357.0736, found 353.0742 (Δ = 1.8 ppm).

(Z)-N-(4-Chloro-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-5-(4-methylbenzylidene)-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-amine (13d): Yield: 78% (0.29 g; 0.78 mmol). Appearance: yellow solid. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.41–7.44 (m, 1H), 7.10–7.17 (m, 5H), 6.54 (s, 1H), 4.57 (s, 2H), 2.33 (s, 3H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 137.3 (C), 132.6 (C), 132.8 (CH), 129.3 (2CH), 128.5 (C), 127.7 (2CH), 126.6 (q, J = 6 Hz, CH), 125.1 (CH), 120.7 (CH), 53.8 (CH2), 21.2 (CH3), not all C observed. 19F-NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −61.9. IR (neat, cm−1) 3083 (w), 3045 (w), 2124 (w), 1902 (w), 1764 (w), 1764 (s), 1625 (m), 1597 (m), 1481 (m), 1468 (m), 1371 (w), 1306 (s), 1268 (m), 1250 (m), 1209 (m), 1195 (m), 1119 (s), 1049 (s), 855 (m), 836 (s), 796 (s), 617 (s), 521 (s), 441 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C18H14ClF3N2S (M + H) 383.0585, found 383.0597 (Δ = −1.2 ppm).

(Z)-5-(2-Bromobenzylidene)-N-(4-chloro-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-amine (13e): Yield: 75% (0.34 g; 0.75 mmol). Appearance: yellow solid. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.11–7.04 (m, 2H), 6.73 (t, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.0 (C), 146.6 (C), 135.7 (C), 134.3 (C), 132.9 (CH), 132.7 (CH), 128.9 (CH), 128.7 (C), 128.3 (CH), 127.5 (CH), 126.6 (C, q, J = 5 Hz), 125.5 (CH), 124.2 (C, q, J = 30 Hz), 123.8 (C), 123.2 (CF3, q, J = 271 Hz), 119.9 (CH), 53.5 (CH2). 19F-NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −61.8. IR (neat, cm−1) 3049 (m), 2898 (m), 1653 (s), 1622 (s), 1483 (s), 1433 (m), 1309 (s), 1193 (m), 1161 (m), 1124 (s), 1101 (m), 1050 (s), 891 (m), 839 (m), 671 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C17H12ClBrF3N2S (M + H) 446.9545, found 446.9559 (Δ = 3.1 ppm).

(Z)-N-(4-Chloro-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-5-(naphthalen-1-ylmethylene)-4,5-dihydro-thiazol-2-amine (13f): Yield: 80% (0.33 g; 0.8 mmol). Appearance: yellow solid. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.97–7.92 (m, 1H), 7.87–7.82 (m, 1H), 7.76 (dq, J = 6.9, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.54–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.36 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.12 (m, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (s, 1H), 4.69 (s, 2H). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.5 (C), 133.1 (C), 132.6 (CH), 131.1 (C), 128.6 (CH), 128.4 (C), 128.3 (CH), 126.5 (CH, m), 126.3 (CH), 126.1 (CH), 125.4 (CH), 125.3 (CH), 125.1 (CH), 123.8 (CH), 123.8 (C), 118.2 (CH), 53.2 (CH2); several C not observed. 19F-NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −61.9. IR (neat, cm−1) 2982 (w), 1627 (m), 1590 (m), 1539 (m), 1484 (m), 1419 (m), 1309 (s), 1290 (m), 1174 (m), 1119 (s), 1050 (s), 795 (m), 686 (m), 641 (m). HR-MS (TOF-ES+) calculated for C21H15ClF3N2S (M + H) 419.0597, found 419.0610 (Δ = 3.2 ppm).

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed a straightforward access to valuable propargylic amines that exploits a telescoped continuous flow approach. This sequence features the safe use of DPPA as the azide source for converting propargylic alcohols into the intermediate azide counterparts. A Staudinger reduction process was used as part of the same sequence to yield the desired propargylic amine species in good yield and purity. Final optimization of this telescoped flow sequence furthermore led to using the more sustainable 2-MeTHF as solvent as opposed to THF and included an in-line extractive work-up. The value of generating these amine products on demand was demonstrated in their effective transformation into drug-like thiazolines, whose correct structural assignment was accomplished by means of a set of single crystal X-ray structures. We believe that this effective entry into propargylic amines will facilitate their further exploitation in future synthesis programs yielding valuable chemical entities.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online: 1H and 13C-NMR spectra of products where an isolated yield is reported.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the research outlined in this article—conceptualization, supervision and funding acquisition M.B.; Performing of experiments, data acquisition and analysis K.D., H.Z. and M.B.; writing and reviewing of manuscript K.D., H.Z. and M.B.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support through the School of Chemistry and University College Dublin (SF1606 and SF1609). We thank Helge Mueller-Bunz for solving the X-ray crystal structures reported in this manuscript. We furthermore acknowledge support by the SSPC through the Pharm5 initiative.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Lauder, K.; Toscani, A.; Scalacci, N.; Castagnolo, D. Synthesis and Reactivity of Propargylamines in Organic Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 14091–14200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uredi, D.; Motati, D.R.; Watkins, E.B. A Unified Strategy for the Synthesis of β-Carbolines, γ-Carbolines, and Other Fused Azaheteroaromatics under Mild, Metal-Free Conditions. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 6336–6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Xie, Z. Atom-Economical Synthesis of N-Heterocycles via Cascade Inter-/Intramolecular C-N Bond-Forming Reactions Catalyzed by Ti-Amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11473–11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamouka, S.; Moran, W.J. Iodoarene-Catalyzed Cyclizations of N-Propargylamides and β-Amidoketones: Synthesis of 2-Oxazolines. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 1823–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peshkov, V.A.; Pereshivko, O.P.; Van der Eycken, E.V. A Walk Around the A3-coupling. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3790–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Li, Z.; Li, C.-J. The Development of A3-Coupling (Aldehyde-Alkyne-Amine) and AA3-Coupling (Asymmetric Aldehyde-Alkyne-Amine). Synlett 2004, 9, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Tu, Y.-Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, F.-M.; Fan, C.-A. Microwave-Promoted Three-Component Coupling of Aldehyde, Alkyne, and Amine via C−H Activation Catalyzed by Copper in Water. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1001–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gommermann, N.; Konradin, C.; Polborn, K.; Knochel, P. Enantioselective, Copper(I)-Catalyzed Three-Component Reaction for the Preparation of Propargylamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5763–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisai, A.; Singh, V.K. Enantioselective One-Pot Three-Component Synthesis of Propargylamines. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 2405–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidwai, M.; Bansal, V.; Kumar, A.; Mozumdar, S. The First Au-Nanoparticles Catalyzed Green Synthesis of Propargylamines via a Three-Component Coupling Reaction of Aldehyde, Alkyne and Amine. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 742–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkait, N.; Okumura, S.; Souto, J.A.; Muniz, K. Hypervalent Iodine Mediated Oxidative Amination of Allenes. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4750–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.; Heo, Y.; Lee, S. Metal-Free Decarboxylative Three-Component Coupling Reaction for the Synthesis of Propargylamines. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3322–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Huang, S. A Microwave-Assisted Three-Component Synthesis of Arylaminomethyl-Acetylenes: A Facile Access to Terminal Alkynes. Synlett 2014, 25, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.G.; Nallagonda, R.; Ghorai, P. Direct Substitution of Hydroxy Group of π-Activated Alcohols with Electron-Deficient Amines Using Re2O7 Catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 5577–5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plutschack, M.B.; Pieber, B.; Gilmore, K.; Seeberger, P.H. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Flow Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11796–11893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallinger, D.; Kappe, C.O. Why flow means green—Evaluating the merits of continuous processing in the context of sustainability. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2017, 7, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.F. Flow chemistry—Microreaction technology comes of age. AIChE J. 2017, 63, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, D.E.; Ley, S.V. Engineering chemistry for the future of chemical synthesis. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 3087–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Baxendale, I.R. The synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) using continuous flow chemistry. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 1194–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lummiss, J.A.M.; Morse, P.D.; Beingessner, R.L.; Jamison, T.F. Towards More Efficient, Greener Syntheses through Flow Chemistry. Chem. Rec. 2017, 17, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, A.R.; Dombrowski, A.W. Emerging Trends in Flow Chemistry and Applications to the Pharmaceutical Industry. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 6422–6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuade, D.T.; Seeberger, P.H. Applying Flow Chemistry: Methods, Materials, and Multistep Synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 6384–6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movsisyan, M.; Delbeke, E.I.P.; Berton, J.K.E.T.; Battilocchio, C.; Ley, S.V.; Stevens, C.V. Taming hazardous chemistry by continuous flow technology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 4892–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, M.; Baxendale, I.R.; Ley, S.V.; Nikbin, N.; Smith, C.D.; Tierney, J.P. A modular flow reactor for performing Curtius rearrangements as a continuous flow process. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steven, A.; Hopes, P. Use of a Curtius rearrangement as part of the multikilogram manufacture of a pyrazine building block. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018, 22, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, S.C.; Edwards, C.E.R.; Martin, B.; Jensen, K.F. Continuous, on-demand generation and separation of diphenylphosphoryl azide. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 3137–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Smith, C.D.; Nikbin, N.; Ley, S.V.; Baxendale, I.R. Flow synthesis of organic azides and the multistep synthesis of imines and amines using a new monolithic triphenylphosphine reagent. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1927–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- For larger reaction scales a series of scavenger columns were used. An automated switching mechanism as described in the literature can be used to streamline this process; please see: Kitching, M.O.; Dixon, O.E.; Baumann, M.; Baxendale, I.R. Flow-Assisted Synthesis: A Key Fragment of SR 142948A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 6540–6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An alternative, yet more complex approach, would be to use in-line analysis by IR to control the dosing rate of the triphenylphosphine reagent. For a leading example, please see: Lange, H.; Carter, C.F.; Hopkin, M.D.; Burke, A.; Goode, J.G.; Baxendale, I.R.; Ley, S.V. A breakthrough method for the accurate addition of reagents in multi-step segmented flow processing. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, V.; Hoyos, P.; Castoldi, L.; Dominguez de Maria, P.; Alcantara, A.R. 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF): A biomass-derived solvent with broad application in organic chemistry. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycock, D.F. Solvent applications of 2-methyltetrahydrofuran in organometallic and biphasic reactions. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2007, 11, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, S.; Castoldi, L.; Murgia, I.; Senatore, R.; Mazzeo, E.; Wackerlig, J.; Urban, E.; Langer, T.; Pace, V. Recent advancements on the use of 2-methyltetrahydrofuran in organometallic chemistry. Mon. Chem. 2017, 148, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasmal, P.K.; Chandrasekhar, A.; Sridhar, S.; Iqbal, J. Novel one-step method for the conversion of isothiocyanates to 2-alkyl(aryl)aminothiazoles. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 11074–11080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshadi, S.; Vessally, E.; Edjlali, L.; Hosseinzadeh-Khanmiri, R.; Ghorbani-Kalhor, E. N-Propargylamines: Versatile building blocks in the construction of thiazole cores. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalacci, N.; Pelloja, C.; Radi, M.; Castagnolo, D. Microwave-Assisted Domino Reactions of Propargylamines with Isothiocyanates: Selective Synthesis of 2-Aminothiazoles and 2-Amino-4-methylenethiazolines. Synlett 2016, 27, 1883–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Gout, D.; Lovely, C.J. Tandem thioacylation-intramolecular hydrosulfenylation of propargyl amines—rapid access to 2-aminothiazolidines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2019, 1726–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Guo, Z.; Huang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Song, H.; Song, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. One-pot copper-catalyzed cascade bicyclization strategy for synthesis of 2-(1H-indol-1-yl)-4,5-dihydrothiazoles and 2-(1H-indol-1-yl)thiazol-5-yl aryl ketones with molecular oxygen as an oxygen source. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds reported are available from the authors. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).