Abstract

Polyalthia belong to the Annonaceae family and are a type of evergreen tree distributed across many tropical and subtropical regions. Polyalthia species have been used long term as indigenous medicine to treat certain diseases, including fever, diabetes, infection, digestive disease, etc. Recent studies have demonstrated that not only crude extracts but also the isolated pure compounds exhibit various pharmacological activities, such as anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, anti-tumor, anti-cancer, etc. It is known that the initiation of cancer usually takes several years and is related to unhealthy lifestyle, as well as dietary and environmental factors, such as stress, toxins and smoking. In fact, natural or synthetic substances have been used as cancer chemoprevention to delay, impede, or even stop cancer growing. This review is an attempt to collect current available phytochemicals from Polyalthia species, which exhibit anti-cancer potentials for chemoprevention purposes, providing directions for further research on the interesting agents and possible clinical applications.

1. Chemopreventive Concepts on Cancer Progression by Using Natural Products against Chronic Inflammation or Oxidative Stress

Cancer has become a chronic disease in modern societies, and the developments of precise personalized medicines and target therapies have been enlarged lately. Although some cancers may be curable, people still find some alternative strategies to prevent cancer progression. Chemoprevention was first introduced in 1976 and referred to the use of a natural or synthetic agent to reduce the risks and/or reverse cancer from developing [1]. The chemoprevention of cancer could be used in primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention pathways to use medicine or agents to prevent tumor formation in a healthy person, who has pre-cancerous lesions or already had cancer, respectively [2].

Collectively, studies have shown that chronic inflammation may be the initiation of cancer [3,4,5]. Thus, chemoprevention may include the concept of inhibition upon inflammation and oxidation to reverse the progress of carcinogenesis and ageing-induced gene mutation [5]. For example, aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), a synthetic drug from the natural substance salicin, from myrtle and willow is a common prescription for its anti-pyretic, analgesic, and anti-platelet aggregation properties. It is accepted that aspirin at low doses triggers lipotoxins production to block cell proliferation and chronic inflammation, which may associate with a lower incidence and recurrence of polyps as well as reduce colon cancer risk [2].

Plants, microbes, animals, marines, and minerals are always the natural sources that scientists could discover new compounds for chemoprevention related to clinical therapeutics [6,7]. Recently, reports have demonstrated that dietary-derived flavonoids (genistein, rutin, epigallocatechin gallate, silmaylin, curcumin, resveratrol, etc.) exhibit distinct anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities [8]. Until now, only some substances have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration [7]. Nevertheless, people who advocate natural medicine or self-healing strategies against diseases may use plant extracts or herbal decoction as daily supplements to achieve the effectiveness of chemoprevention [6,8].

2. Polyalthia Genus Plants

The genus Polyalthia belongs to the Annonaceae family [9]. It is a type of flowering plant found in tropical and subtropical regions, including South Asia, South East Asia, and Australia [9]. According to the project of the world flora online webpage (http://www.worldfloraonline.org/ accessed on 28 July, 2021), the Polyalthia genus has 127 accepted species, consisting of trees, shrubs, and rare lianas [9]. In India, the Polyalthia longifolia is also called Ashoka or Indian mast tree due to its special appearance as a Stupa [10]. In Taiwan, it is commonly cultivated as landscape trees to avoid noise pollution (Figure 1A). P. longfolia is a tall (up to 12 m) and evergreen tree that grows symmetrically and produces green foliage (Figure 1B). The branches of the tree are peculiar, dropping down toward ground, giving the plant a narrow slender shape. These features make it readily available and is used in many folk medicines for the treatment of various ailments.

Figure 1.

Photographs of P. longifolia Sonn. Thwaites pendula. (A) The whole tree, (B) leaves, and (C) stem bark of P. longifolia. Photos were shot at Kaohsiung, Taiwan, in 17 August, 2021.

Methods for Extraction of Phytochemical Compounds from Polyalthia

Through literatures review, the common method to extract the phytochemical compounds from species in Polyalthia is using organic solvent and followed by traditionally chromatographic techniques, such as column chromatography, high-performance liquid chromatography, etc. Because of the convenience and economic choice, most laboratories used methanol or ethanol as a polar protic solvent to prepare the crude extracts [11]. Methanol and water are better solvents to prepare plant decoction due to its high dielectric constants and dipole moments [11]. Additionally, the evaporation process is easier for methanol when compared to water. For example, the standardized extraction of P. longifolia was through adding dried samples (leaves (Figure 1B), twigs, flowers, fruits, barks (Figure 1C) and/or roots) to adequate volume of methanol and soaked the samples for 3-7 days at room temperature [11,12,13,14]. Filtrated samples were then concentrated by using a rotary evaporator and at 40–60 °C [12,13]. The concentrated extracts could be sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 µm membrane before further testing [11]. Finally, a thick, yellow-to-brownish-colour paste mass was the crude extracts of P. longifolia. The acute oral toxicity of the standardized extracts of P. longifolia leaves has been evaluated to be safe, and the dose can be used at 3240 mg/kg in Wistar albino rats [15] and at 5000 mg/kg in female Sprague-Dawley rats [16].

Generally, the discovery of the newly phytochemical compounds from natural sources is based on the bioactivity-guided fractionation, purification, and structure identification [17]. The fractions were then tested for their activities on the cytotoxic, anti-oxidant or anti-inflammatory effects. The active fractions will be chosen for further isolation of the bioactive compounds. Sometimes, the resolution of enantiomers is not easy and needs particular chromatographic columns to separate the distinct substances from each other [11,17]. In addition to the consumption of a large quantity of organic solvents, which may also raise the concerns of environmental pollution, the isolation and identification of the biochemical compounds from these fractions are time-consuming and labour-intensive processes that increase the difficulties of finding new compounds.

3. Phytochemical Constituents in Species of Polyalthia

Scientific reports on leaves, bark, stem bark, root, twigs, and seeds of Polyalthia have revealed dozens of types of alkaloids and terpenes with numerous biological and pharmacological activities with chemopreventive potentials, such as anti-bacterial [18,19,20], anti-fungal [21], anti-viral [22,23], anti-plasmodial [24,25,26], anti-inflammatory [27,28,29], anti-ulcer [30], anti-tumor [31,32,33], and anti-cancer [34,35,36] effects.

Literature reviews on recent works reveal that most abundant phytochemicals in Polyalthia plants are alkaloids and terpenes [37]. Other major bioactive phytochemicals in Polyalthia species are flavonoids, lignans, sterols, organic acids, etc. [27,38,39,40,41,42]. In fact, clerodane-type diterpenes may be one of the most well-studied and enriched-compound in Polyalthia species, and the pharmacological and physiological functions of 16-hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-15,16-olide (36 and/or 38, abbreviated CD or HCD in literatures) have been studied by several groups [24,43,44,45,46,47].

CD, a major component of P. longifolia [14], has been validated to exhibit anti-microbial [24,48,49,50], anti-diabetic [51], anti-tumor [34,44,45,52], and anti-cancer [36,43] activities. Moreover, molecular docking studies have shown that 36 can be a multi-targets inhibitor to 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl co-enzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase [46], dipeptidyl peptidase 4 [51], focal adhesion kinase (FAK) [53], and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) [45]. Besides, to compile the promising compounds that display chemopreventive activities, the molecular mechanisms of CD, one of the most potent agents isolated from P. longifolia, will be illustrated later.

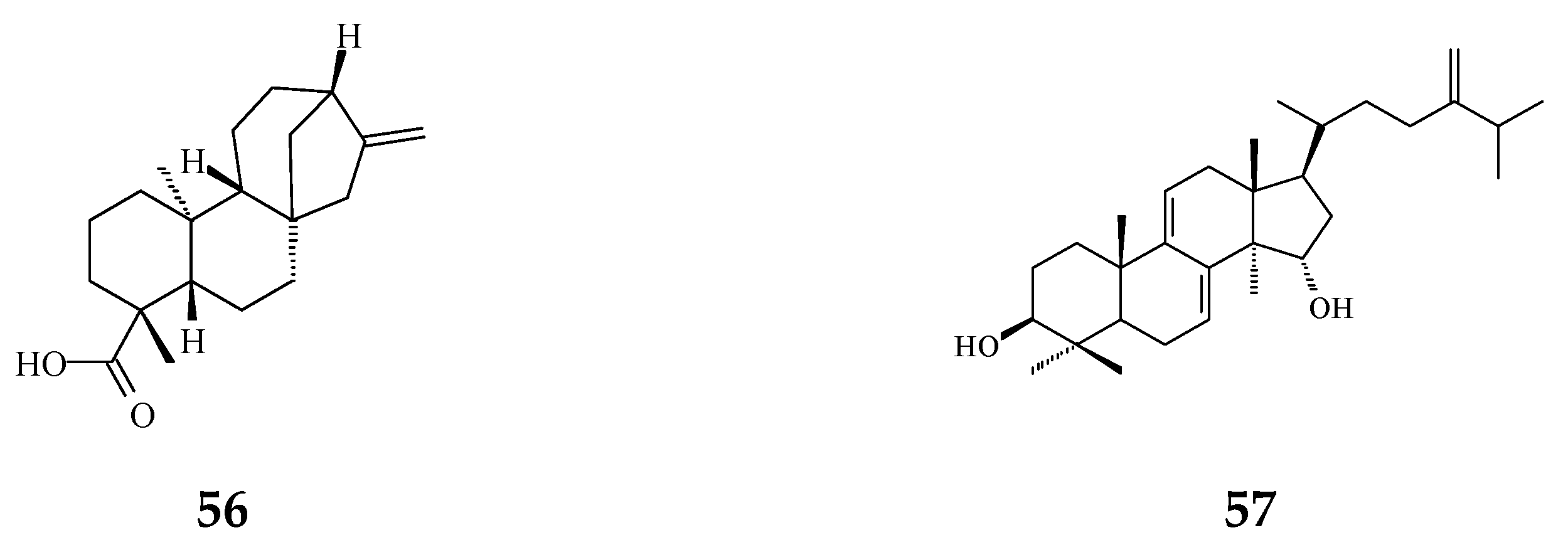

4. Anti-Oxidant Phytochemicals in Polyalthia

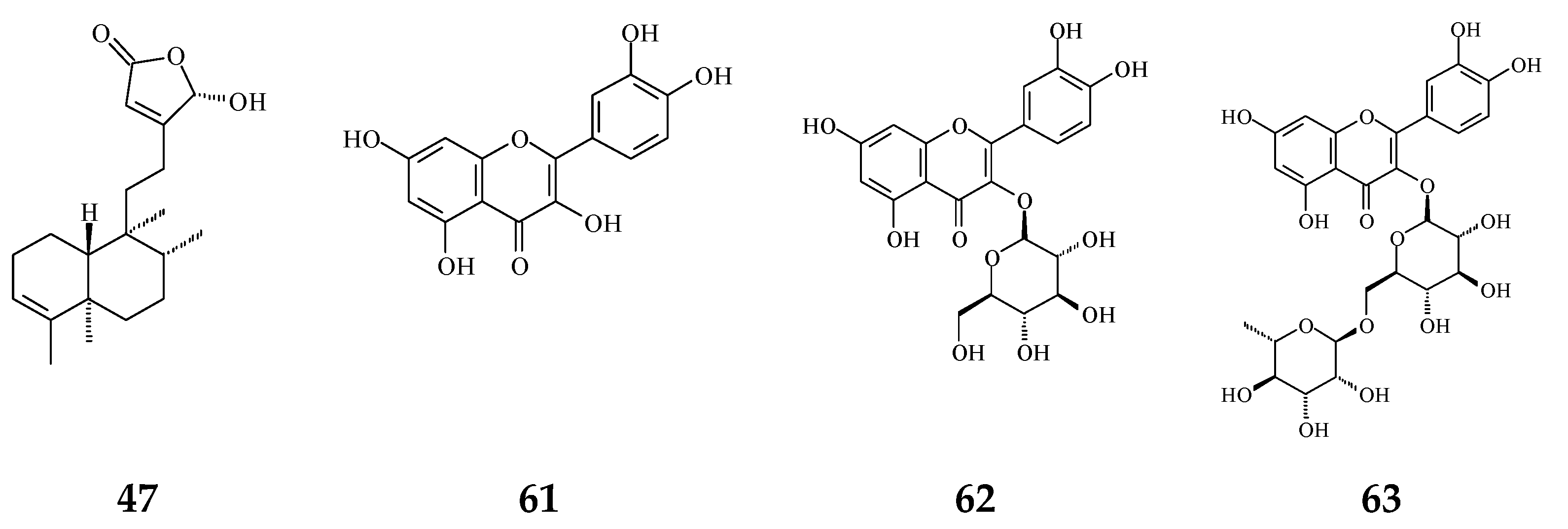

Plant extracts and natural products are sources of anti-oxidative agents. As reported (Figure 2), flavonoids (61–63) [54,55] and proanthocyanidins [56] extracted from P. longifolia leaves and clerodane diterpenes (47) isolated from stem bark of P. simiarum [57] as well as stem bark of P. longifolia extracts [58] displayed anti-oxidative activities, as detected by the DPPH method and enzymatic activity assay.

Figure 2.

The phytochemical compounds isolated from species of Polyalthia with anti-oxidant activity (47 and 61–63).

Oyeyemi et al. (2020) demonstrated that P. longifolia aqueous and methanolic leaf extracts present the prophylactic and the curative activities against cadmium (a major environmental pollutant)-induced hepatotoxicity by relieving the oxidative stress in rats [59]. Moreover, phenol- and flavonoids-rich P. longifolia extracts have been demonstrated to improve paracetamol-treated rat liver injury related to free radicals [55]. In fact, Rai et al. (2019) have found that flavonoids from P. longifolia could block fructose-induced protein oxidation and glycation as well as the formation of advanced glycation end products [41]. Shih et al. (2010) have demonstrated that CD could ameliorate LPS-induced toxicity through the inhibition of redox signalling upon inducible nitric oxide synthase and gp91 (phox) in microglia cells [60]. All above studies suggest that the observed hepatoprotective and improvement of cell survival by P. longifolia extracts or clerodane diterpenes were related to their anti-oxidant activity.

Oxidation and anti-oxidation could be a double-edged sword, and the imbalance of redox signalling could cause oxidative stress [61]. It is well known that ageing, inflammation, environmental pollutants and ultraviolet radiation could promote to produce a large quantity of free radicals [61]. On the other hand, reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction has been contributed to an intrinsic apoptotic pathway in cancer research [62], which would trigger the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, and then to induce caspase-9 and -3 cleavages, initiating cell apoptosis [62]. In fact, CD could promote ROS overproduction, which can be seen in some in vitro tumor cell lines [34,44,52]. One study has shown that CD enhanced ROS production, which concomitantly inhibited the activity of antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione transferase in glioma cells [34].

5. Anti-Inflammatory Phytochemicals in Polyalthia

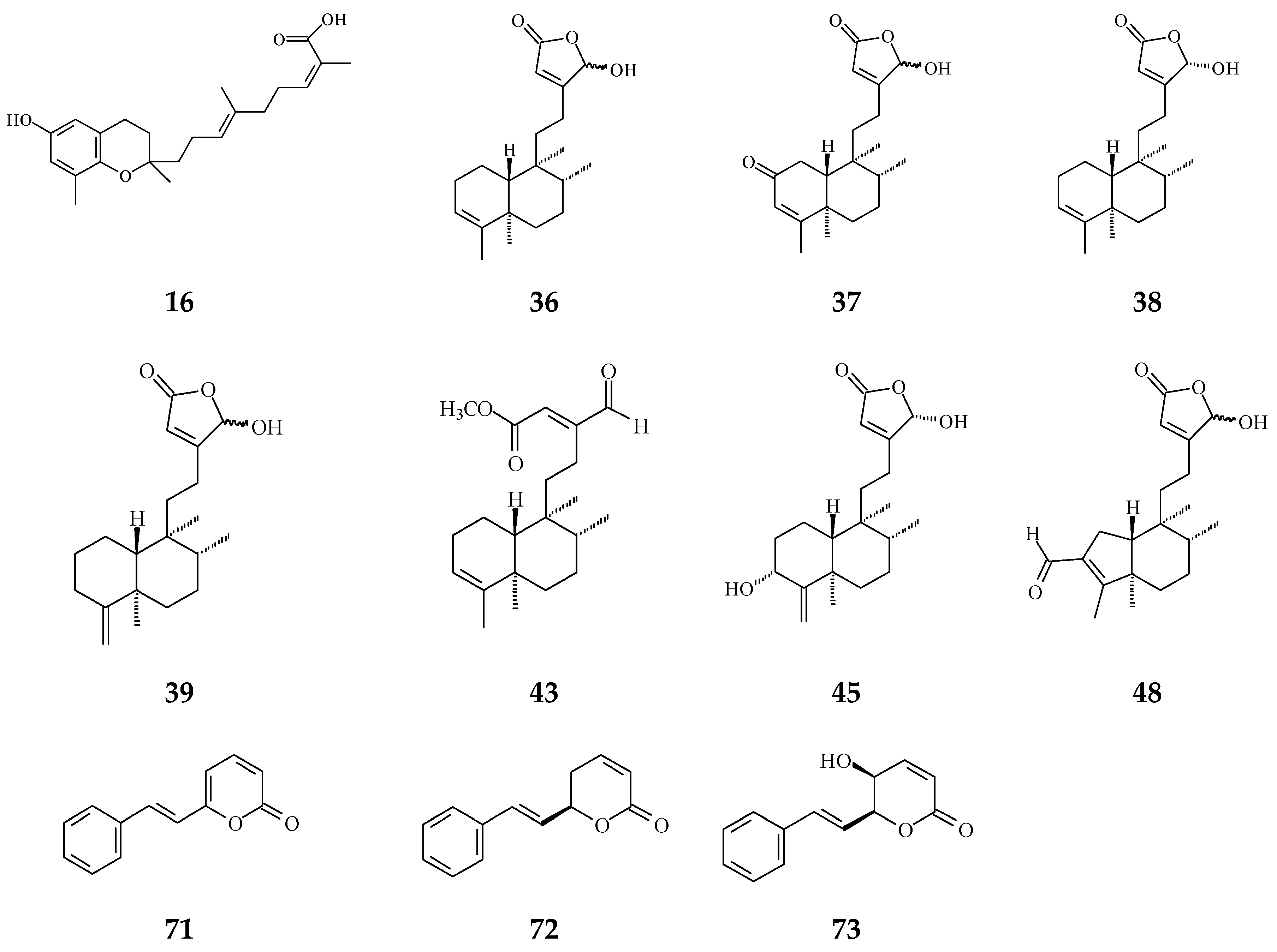

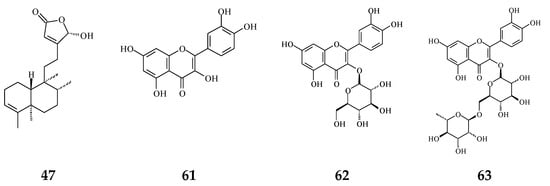

Inflammation plays a crucial role in carcinogenesis [3]. During tissue injury, a large number of cytokines and chemokines are attracted to the afflicted region to initiate and activate tissue-repairing processes [63]. Anti-inflammatory cytokines and pro-inflammatory cytokine signals are in balance, regulating normal inflammation conditions [63]. However, a growing body of evidence has shown that chronic inflammation or persistent infection are the main factors to induce tumor development [4,5]. Regardless of early in neoplasia formation or later in tumorigenic progress, inflammatory immune cells and the tumor itself would release many cytokines/chemokines and angiogenic factors, which would make a suitable microenvironment contributing to cancer deterioration [3]. The crude extracts of Polyalthia plants have been evaluated upon the anti-inflammation effects using in vitro and/or in vivo models. In Figure 3, several compounds from Polyalthia plants, including polycerasoidol (16) from P. cerasoides [28], 36–38, 43, 45, and 48 from P. longifolia [27,64], and 6S-styryllactones (71–73) from P. parviflora leaves [65], have revealed the anti-inflammation activities.

Figure 3.

The phytochemical compounds isolated from species of Polyalthia with anti-inflammatory activity (16, 36–39, 43, 45, 48 and 71–73).

Study has also shown that polycerasoidol (16) could decrease tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα-induced mononuclear cell adhesion to human umbilical endothelial cells at a concentration of 4.9 μM [28]. In addition, this prenylated benzopyran compound (16) was reported to be a dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-agonists using in vitro activity assay plus prediction by molecular docking simulation, preventing cardiovascular events associated with metabolic disorders [28]. In addition to their anti-inflammatory function [66], PPAR and PPAR agonists have been shown to treat dyslipidaemia or type II diabetes, respectively [67], which could correlate to the phytochemicals in the Polyalthia genus with an anti-inflammatory characteristic. Indeed, dual PPAR agonists may combine both advantages to achieve more potent therapeutic application, which is ongoing in preclinical and clinical trials [68,69].

Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and anti-pyretic drugs commonly used today are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which inhibit COX-2 activity and stop the downstream prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production and the following inflammatory process [70]. The leaves, stem bark and root extracts of P. longifolia (300 mg/kgw) express higher activities against LPS-induced pyrexia than aspirin [71]. In fact, studies have demonstrated different effects of phytochemicals in the Polyalthia genus, such as that anti-inflammatory effects of 36 and 41 [64] have been authenticated on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated RAW264.7 macrophages; 16-oxocleroda-3,13(14)E-dien-15-oic acid methyl ester (43) could inhibit formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-l-phenylalanine/cytochalasin B (fLMP/CB)-induced superoxide anion generation in human neutrophils [27]; 36 could ameliorate LPS-induced nitric oxide (NO) production in RAW264.7 macrophages [64] as well as inhibit LPS-induced neurotoxicity through the down-regulation of COX-2 and NF-κB (p65) [60]; and the production of NO and inflammatory cytokines (PGE2, and TNFα) were all reversed by the 36 treatment [60].

The anti-inflammation activity of 16-hydroxycleroda-3,13Z-dien-15,16-olide (38), 16-hydroxycleroda-4(18),13-dien-15,16-olide (39), and 3,16-dihydroxycleroda-4(18),13(14)Z-dien-15,16-olide (45) have been determined by kinases inhibition assays upon cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and -2 (COX-2) as well as 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) [29]. Specifically, 38 displays an excellent inhibition rate against COX-1 enzyme compared to indomethacin (COX-1 reference drug) at 10 μg/mL. It also shows better inhibition on 5-LOX enzyme than diclofenac (23.28 ± 0.31 nM). Furthermore, molecular docking and calculation binding affinities show that these two compounds are potent COX-1/2 and 5-LOX inhibitors [29], implying that both compounds could be possibly used for clinical application against inflammation as precise personalized medicines.

Furthermore, using an in vivo model, CD could improve azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate-induced IBD, which included a reduction in lymphocyte infiltration, lymphatic nodule enlargement, and shorter villi of the intestine [72]. Taken together, CD (36 and/or 38) could alleviate inflammation, which may link to COX-2 and NF-κB signaling pathways related to the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and NO release.

6. Cytotoxic/Anti-Tumor Phytochemicals in Polyalthia and the Molecular Mechanism of CD-Induced Tumor Cell Death

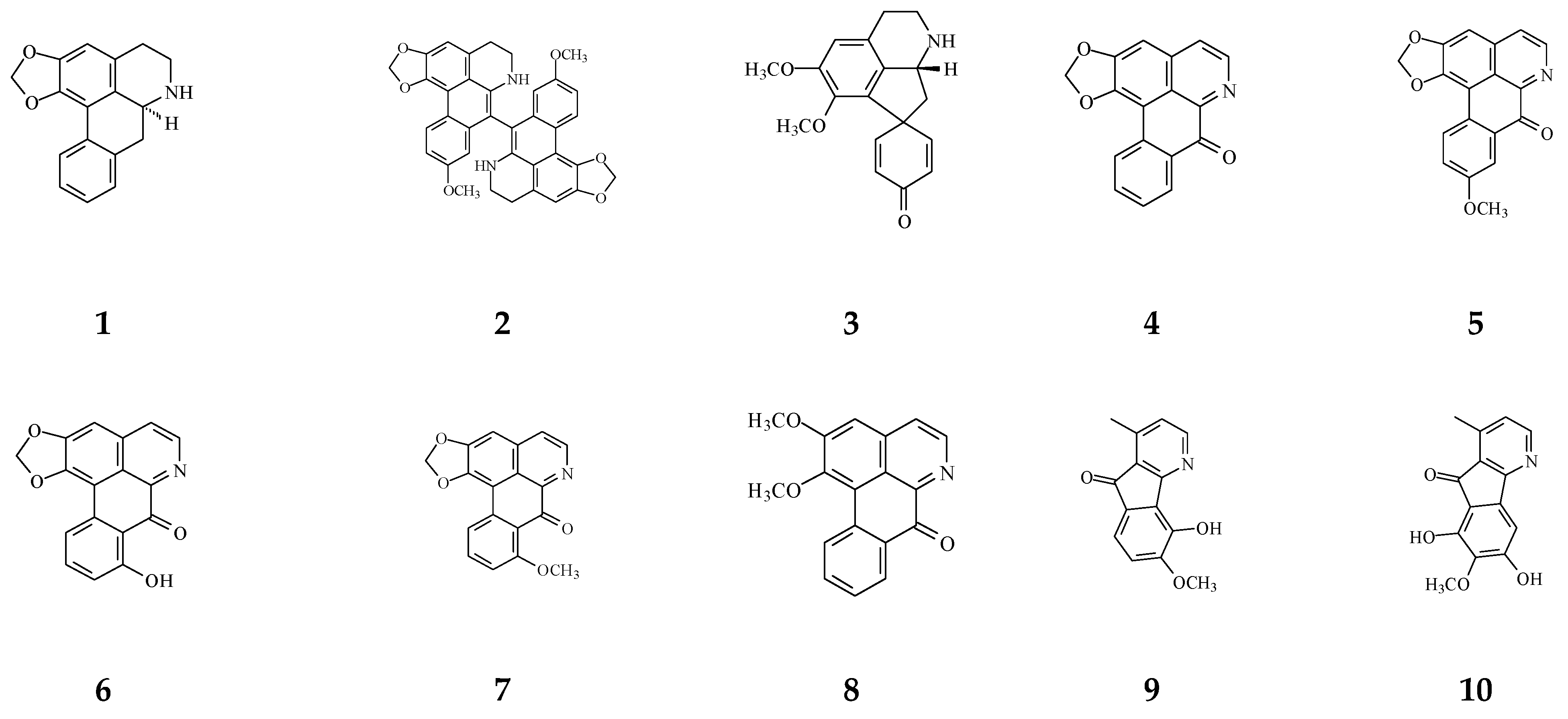

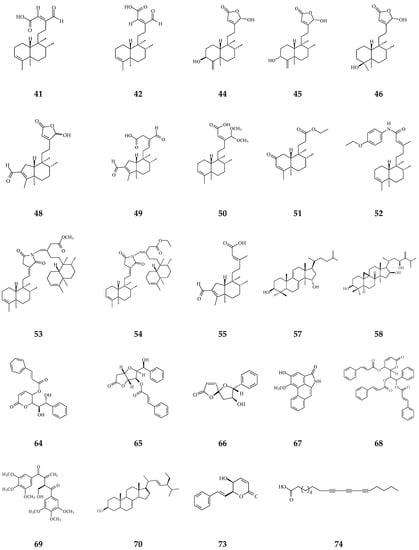

Cytotoxic compounds isolated from Polyalthia mainly belong to alkaloids and terpenes, which are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 4. By using survival tests (MTT or CCK-8), there are about 54 compounds exhibiting cytotoxic/anti-tumor effects, which show that IC50 values are in the range of nano-molar to micro-molar.

Table 1.

Bioactive compounds isolated from Polyalthia plants.

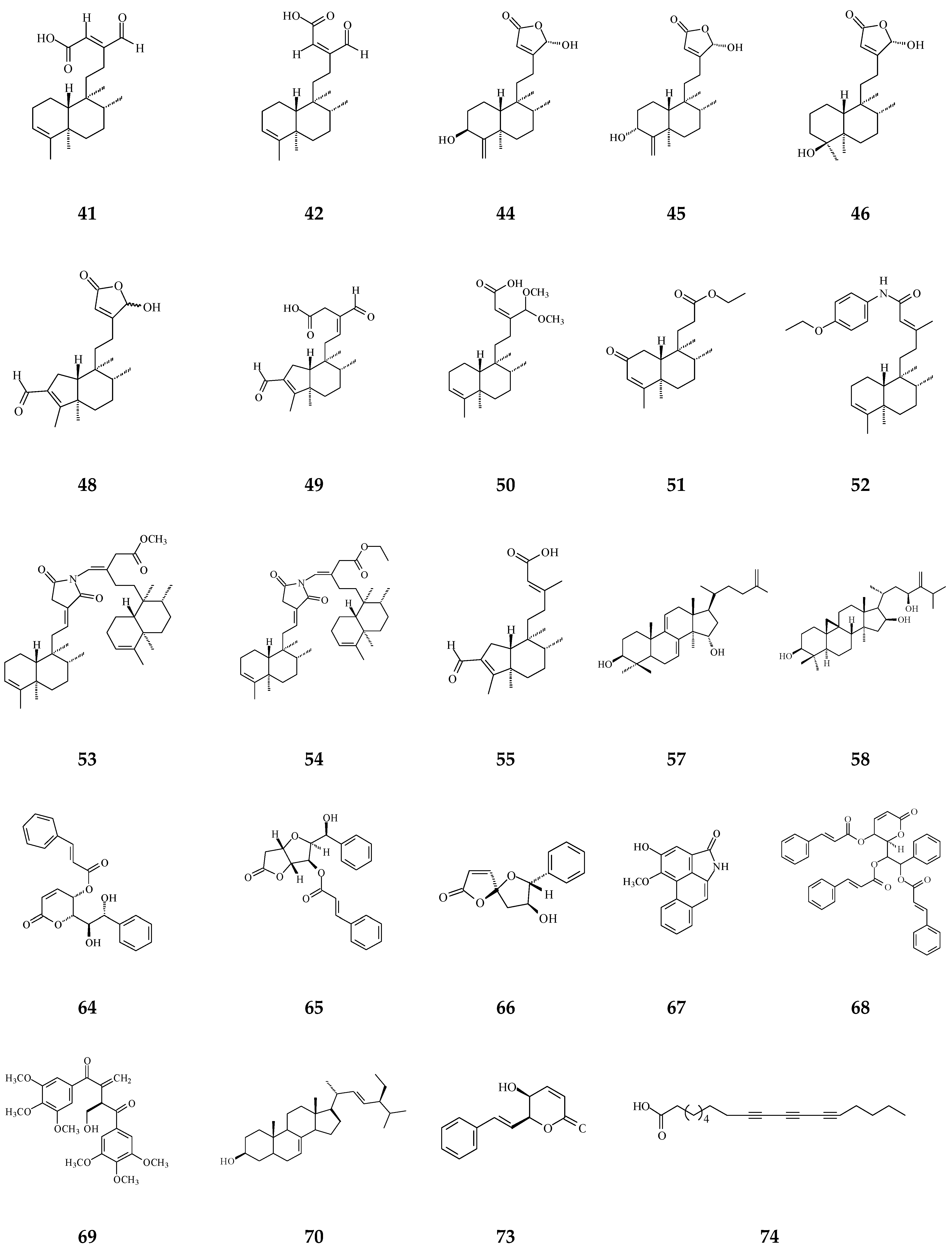

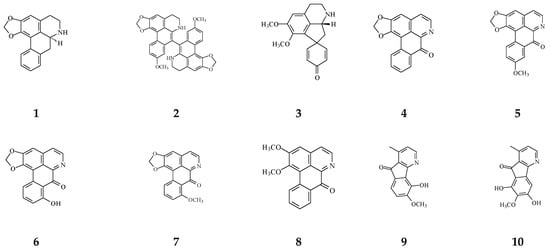

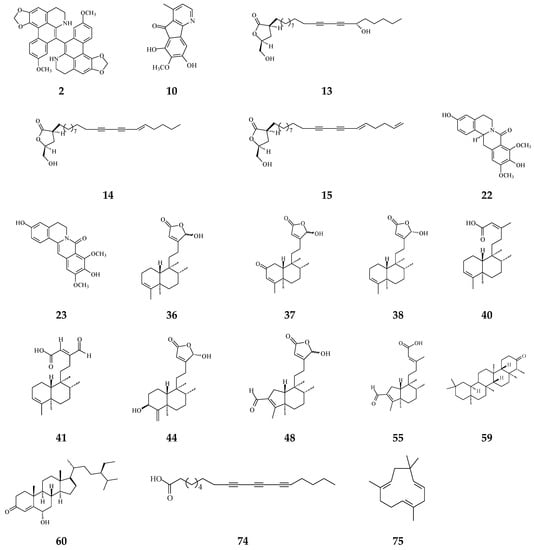

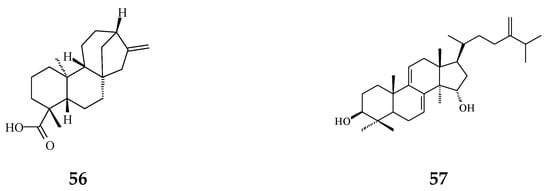

Figure 4.

The phytochemical compounds isolated from species of Polyalthia with cytotoxic/anti-tumor activity (1–12, 15, 21, 24–36, 38–42, 44–46, 48–55, 57, 58, 64–70, 73, 74).

Eighteen alkaloid compounds, namely, (−)-anonaine (1), bidebiline E (2), (+)-stepharine (3), liriodenine (4), lanuginosine (oxoxylopine) (5), oxostephanosine (6), oxostephanine (7), Lysicamine (8), 5-hydroxy-6-methoxyonychine (isoursuline) (9), 6,8-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1-methyl-azafluorenone (10), polylongine (11), marcanine A (12), debilisone E (15), 21-(2-furyl)heneicosa-14,16-diyne-1-ol(21), (−)-8-oxo-2,9,10-trihydroxy-3-methoxyberberine (consanguine B) (24), (−)-stepholidine (25), N-trans-feruloyltyramine (26), and N-trans-p-coumaroyltyramine (27), could induce cancerous cell death at a concentration of µg/mL or µM range. Compound 10 induces cell apoptosis in HL-60 through cleavage of caspase-8 and -9, indicating the activations of extrinsic and intrinsic caspase pathways. Besides, 10 has been tested on the adriamycin-resistant lung cancer cell line with an IC50 value of 3.6 µg/mL.

Twenty-seven terpene compounds, namely, polyalone A (28), 9-ketocyclocolorenone (29), blumenol A (30), (−)-methyl dihydrophaseate (31), bis-enone (32), longimide A (33), labd-13E-en-8-ol-15-oic acid (34), 1-naphthaleneacetic-7-oxo-1,2,3,4,4a,7,8,8a-octahydro1,2,4a,5-tetramethyl acid (35), 36, 16α-hydroxycleroda-3,13Z-dien-15,16-olide (38), 16-hydroxycleroda-4(18),13 -dien-15,16-olide (39), kolavenic acid (40), 16-oxocleroda-3,13E-dien-15-oic acid (41), 16-oxocleroda-3,13Z-dien-15-oic acid (polyalthialdoic acid) (42), 3β,16α-dihydroxycleroda-4(18),13(14)Z-dien-15,16-olide (44), (-)-3α,16α-dihydroxycleroda-4(18),13(14)Z-dien-15,16-olide (45), 4β,16α-dihydroxycleroda-13(14)Z-en-15,16-olide (46), (4→2)-abeo-16(R&S)-2,13Z-clerodadien-15,16-olide-3-al (48), (4→2)-abeo-2,13-diformyl-cleroda-2,12E-dien-14-oic acid (49), 16,16-dimethoxy-cleroda-3,13Z-dien-15-oic acid (50), polylauiester A (51), polylauiamide B (52), polylauiamide C (53), polylauiamide D (54), solidagonal acid (55), suberosol (57), and 24-methylenecycloartane-3β,16β,23β-triol (longitriol) (58), could reduce cell viabilities. Compounds 33, 37, 39, 41, 42, 44, 46, and 48 showed the best potency (IC50 values are below 5 µg/mL) against some tumor cell lines (Table 1).

Other natural products include crassalactone A (64), crassalactone B (65), crassalactone D (66), aristolactam AII (67), (+)-tricinnamate (68), (+)-rumphiin (69), -spinasterol (70), (−)-5-hydroxygoniothalamin (73), and octadeca-9,11,13-triynoic acid (74), which are not yet classified in the alkaloid or terpene family displaying cytotoxic effects against several tumor cell lines. Compounds 64–68 from P. crassa affect tumor cell growth at very low IC50 values in the range of 0.18–3.8 µg/mL [96]. However, the concentrations of these compounds may also hurt normal cells. Compounds 44 and 45 display cytotoxicity against both human tumor cell lines and the normal green monkey kidney epithelial cell line [77]. Longimide A (33) at a lower concentration (4.12–10.13 µg/mL) kills several tumor cell lines, while the cytotoxic concentration is 4 to 10-fold higher on the NIH-3T3 normal fibroblast cell line [83]. The IC50 value of longitriol (58) could inhibit breast and brain tumor cell proliferation and then induce apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines. At a concentration of 40.3 µM, 58 is also toxic on MRC-5 normal human fibroblasts. Therefore, the most toxic compound may not be a good agent for therapeutic application, which should be further authenticated by using an in vivo model.

Rupachandra and Sarada (2014) determined a fraction F2 purified from trypsin-treated P. longifolia seeds and found that F2 fraction caused A549 and HL-60 cell death through apoptosis [98]. They showed the average mass of this F2 fraction to be 679.8 m/z ratios by LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis; however, the exact structure was not shown [98].

There are many selective candidates for biological and pharmacological studies related to the accessibility of these specific compounds, which may need to be considered. In comparison to other cytotoxic alkaloids (milligram level output), the extraction of 9 kg of P. longifolia leaves could obtain about 12.2 g of 16-hydroxycleroda, 3,13-dien, 15,16 olide (38) [14] with a good yield rate, which does elevate its potentiality as a drug/medicine.

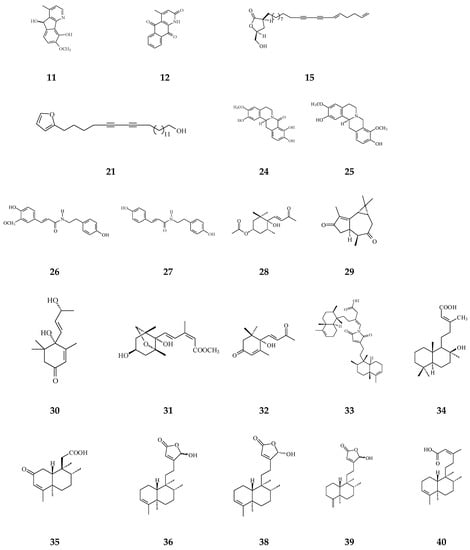

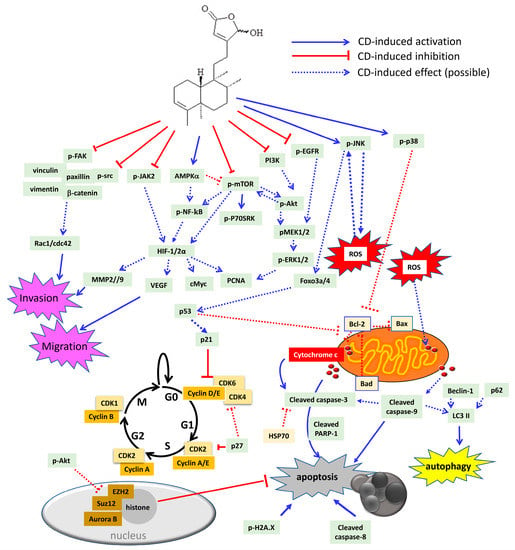

At the concentration of 20–40 µM, CD (36) reduced tumor cell proliferation in solid tumors, such as glioma [34,43], glioblastoma [45], urothelial [44,52,100], breast [27], colon [45,72], lung [45], hepatoma [72], and head and neck [36] carcinoma cell lines, and in liquid tumors (leukemia) [45,86,99], respectively. Among these isolated compounds from Polyalthia, CD is the well-studied compound in anti-cancer fields. Accordingly, CD could become a potential agent, which may target multiple signalling molecules, including oncogenic, inflammatory, migratory, and invasive pathways (Figure 5 and Table 2).

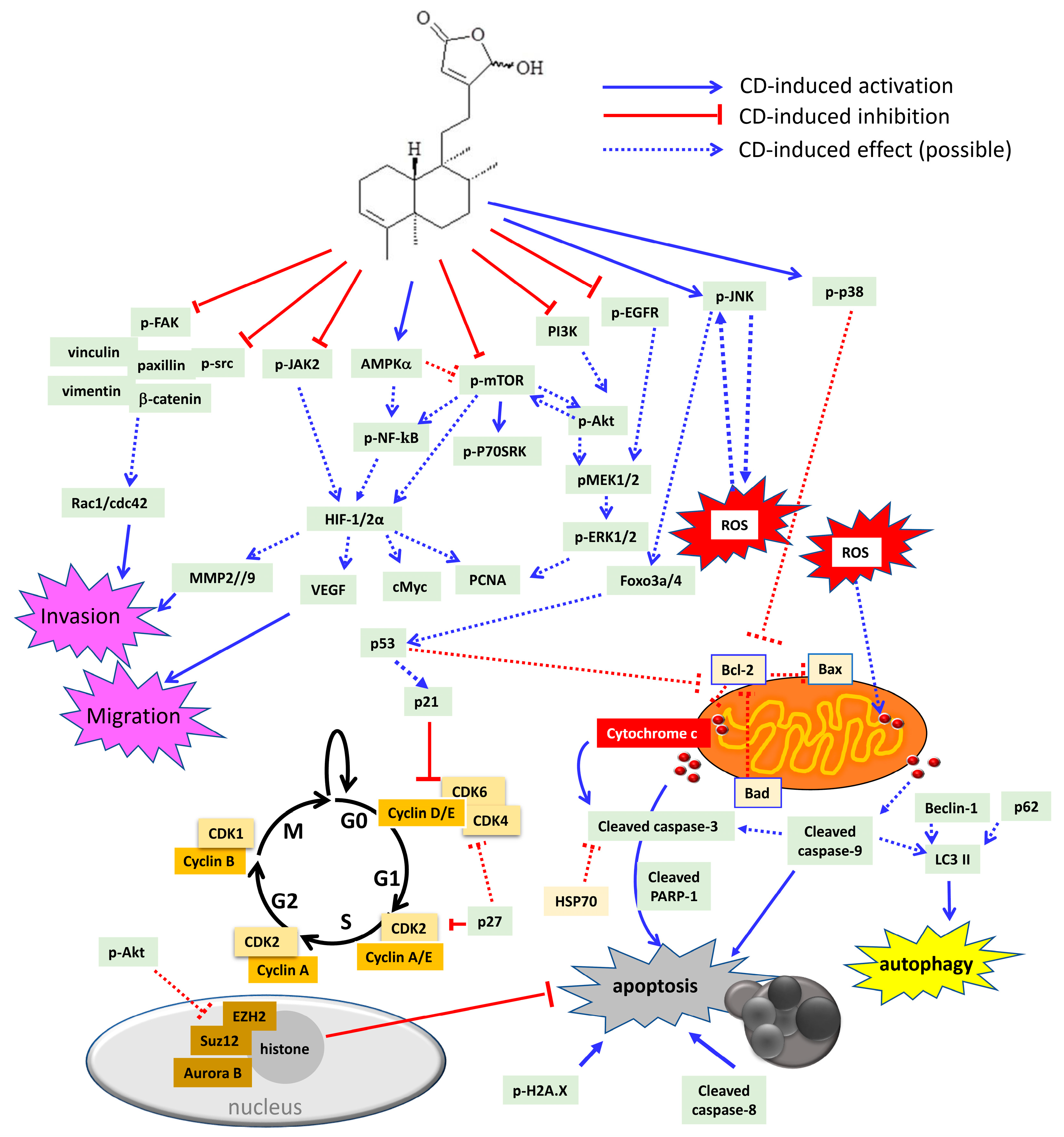

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of CD-induced possible molecular mechanisms in different tumor cells. CD could block cell proliferation through inactivation of several oncogenic molecules, including dephosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), PI3K, Akt, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta 1 (P70S6K), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2), extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), and src. Besides, CD could also arrest cell cycle either at G0/G1 or G2/M phase through inhibition of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), as well as induction of the CDK inhibitor, p21, p27, and p53, respectively. In addition, CD could increase sub-G1 population, which indicates DNA fragmentation related to cell apoptosis. CD can trigger cell death via autophagy and/or apoptosis. CD has been shown to be involved with H2A.X phosphorylation as well as cleavage of caspase-3, -8, -9, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) to induce intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis. Moreover, CD could promote ROS overproduction, which may induce cytochrome c release from the mitochondria outer membrane. The anti-apoptotic proteins that CD could suppress are heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) and B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2). The pro-apoptotic proteins that CD could stimulate are Bad and Bax. Accordingly, CD induces phosphorylation of C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 MAPK, and 5’ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). JNK has been linked to ROS generation, which may cause a positive feedback loop to further activate JNK itself. Activation of p38 MAPK has been demonstrated to reduce Bcl-2 expression and trigger the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. As a tumor suppressor, forkhead box O3 (foxo3a), foxo4 as well as p53 can be up-regulated by CD treatment. The induction of p53 by CD may cause CDK inhibitor p21 to impede cell cycle, or, on the other hand, induce Fas/caspase-8 and initiate extrinsic apoptotic cascade. CD could repress the polycomb repressive comb complex (PRC)2 by modulating enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) and suppressor of zeste 12 homolog (Suz12) as well as regulating histone demethylation to induce apoptosis. The inflammatory signalling pathway includes Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) and NF-κB, which could be both inactivated by CD treatment. CD could abrogate hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) 1 and 2 expression. Additionally, the HIF-downstream molecules, such as cMyc, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2 and MMP9), could all be down-regulated by CD. Moreover, CD can induce cancer cell anoikis by dephosphorylation of the FAK pathway to abolish FAK-associated proteins, including vinculin, paxillin, vimentin, β-catenin, and src kinase. Rac1 and cdc42 protein expression are also down-regulated by CD.

Table 2.

Anti-tumor effects of 16-hydroxycleroda, 3,13-dien, and 15,16 olide on different cancer cell lines.

Oncogenic pathways, such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and PI3K/Akt signalling cascades, mainly contribute to tumor proliferation and cell survival [101]. Inhibitions of ERK1/2 and/or PI3K/Akt pathways by CD would suppress tumor cell proliferation and tumor growth, which have been well investigated and illustrated in RCC [44] and bladder cancer cell lines [52]. However, up-regulation of C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 MAPK, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, concomitantly with the induction of apoptosis by CD, was also seen in glioma and leukemia cell lines [34,45]. In fact, CD could inhibit cell proliferation through cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase [44,45] or G0/G1 phase [34,36,52]. Moreover, tumor suppressor proteins, such as p53, FoxO3a and FoxO4, could be increased by CD in RCC [44] and leukemia cancer cell lines [45] to induce cell apoptosis. Stress-activated JNKs, p38 MAPK, and ERK are double-face kinases in regulating cell death and survival, and this may because of a complex cross-talk network and/or a positive feedback loop exhibiting in cells [102]. Reports have shown that ROS generation activates JNK/p38 MAPK, which in turn induces ROS elevation in a feedback loop [103,104,105].

It is well accepted that NF-κB serves as an essential moderator in modulating inflammation through induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines [106]. Study has shown that transcription factor NF-κB would have cross-talk with other signalling pathways, such as FAK, mTOR or PI3K/Akt [106], to regulate inflammation, and the inhibition of pNF-κB by CD did affect inflammation response in colon cancer [72] cell line. Accordingly, it is highly possible that CD could alleviate inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which may also relate to the inactivation of the NF-κB pathway.

Beside the inactivation of those proliferative and pro-inflammatory signaling cascades, Shanmugapriya et al. (2019 and 2020) reported that polyphenol-rich P. longifolia extracts induced HeLa cell apoptosis by down-regulation of oncogenic micro-ribonucleic acid (miRNA)-221-5p in HeLa cells [107,108]. MicroRNA is a non-coding small RNA, which consists of about 21-25 nucleotides in length and is base-pairing to the targeted messenger RNA (mRNA) [109]. The major function of miRNA appears to repress gene expression by the inhibition of translation, promotion of mRNA cleavage, and deadenylation [109]. A single miRNA is able to control up to hundreds (or more) mRNA; therefore, any mis-expression or mis-regulation of miRNA could lead to the development of tumor cells [110]. In summary, more studies are required to further clarify the relationship between the miRNAs and the silenced genes under the administration of crude extracts or an isolated single compound in Polyalthia.

7. Anti-Cancer Potential of Polyalthia Genus

Although there are hundreds of chemicals isolated from species of Polyalthia, few studies illustrate the investigation on anti-cancer activity of the single compound or Polyalthia extracts. Afolabi et al. (2020) provide the evidence that methanol extracts of P. longifolia exhibited anti-cancer activity against metastatic prostate cancer [35]. This study shows that methanol extracts of P. longifolia promoted the activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and induced intrinsic apoptotic pathways [35]. Through proteomic and biochemical analysis, the glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78/BiP) was determined as a crucial starter to initiate ER stress and induce cell apoptosis [35]. One of the possible compounds that lead to impede prostate cancerous cell growth may be the tetranorditerpene 1-naphthalene acetic-7-oxo-1,2,3,4,4a,7,8,8a-octahydro-1,2,4a,5-tetramethyl acid (35) [35], which could also inhibit human leukemia HL-60 cell proliferation [84].

CD (38) has been determined as a new structural class of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor [46] that alleviates adipogenesis in vitro and in vivo [47]. An FDA-approved drug, statin, a well-known inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase, is now undergoing clinical trials for combination with standard chemotherapy or with other molecular-targeted drugs to improve cancer patients’ treatment outcomes and overcome drug resistance [111]. Velmurugan et al. (2018) reported that CD (36) enhances tamoxifen-induced apoptosis in both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells [112]. It is expected to soon have the investigation of HMG-CoA reductase-mediated molecular mechanism by CD treatment on some aberrant sterol metabolic cancer subtypes, such as ER-negative breast cancer and RCC.

Lin et al. (2011) demonstrated that CD is an inhibitor for PI3K. Moreover, the CD-inactivated Akt pathway may link to suppress the PRC2 complex and to reactivate downstream tumor suppressor gene expression. They also demonstrated that CD potentiates imatinib-induced cell death in K562, T315I-Ba/F3, SW620, and A549 cell lines. Taken together, CD may possibly be developed in combination with other clinical agents for tumor treatments.

Cheng et al. (2016) demonstrated that CD inhibited head and neck cancer growth by using the xenograft model, which showed that the effective intraperitoneal injection dosages were 6.5 and 19.5 mg/kgw/2 day by a seven-round treatment course [36], respectively. CD, like many other natural products, is insoluble in water. The poor bioavailability limits its effectiveness and usefulness in clinical therapeutics. The same group showed that enteric-coated nanoparticles of CD with intraperitoneal injection displayed more potently effective dosage with 0.16 mg/kgw/daily for a 10-day treatment period [43].

Hussain et al. (2018) evaluated a semi-synthetic diterpenoid, 16(R&S) phenylamino-cleroda-3,13(14)Z-dien-15,16 olide (derived from 16-oxocleroda-3,13(14)E-dien-15-oic acid (41), which could inhibit neuroblastoma SH-5Y5 cell proliferation through modulating the p53 pathway and apoptosis [113]. The IC50 of this semi-synthetic compound is 12.5 µM for 48 h of treatment in SH-5Y5 cells, which could be comparative with cisplatin administration [113]. Additionally, authors suggested that this agent did not affect the renal system in vivo, which could be considered for further cancer treatment.

8. Chemoprevention Potential of Phytochemical Compounds from Polyalthia

8.1. Phytochemical Compounds with Anti-Bacterial and Anti-Fungal Activities

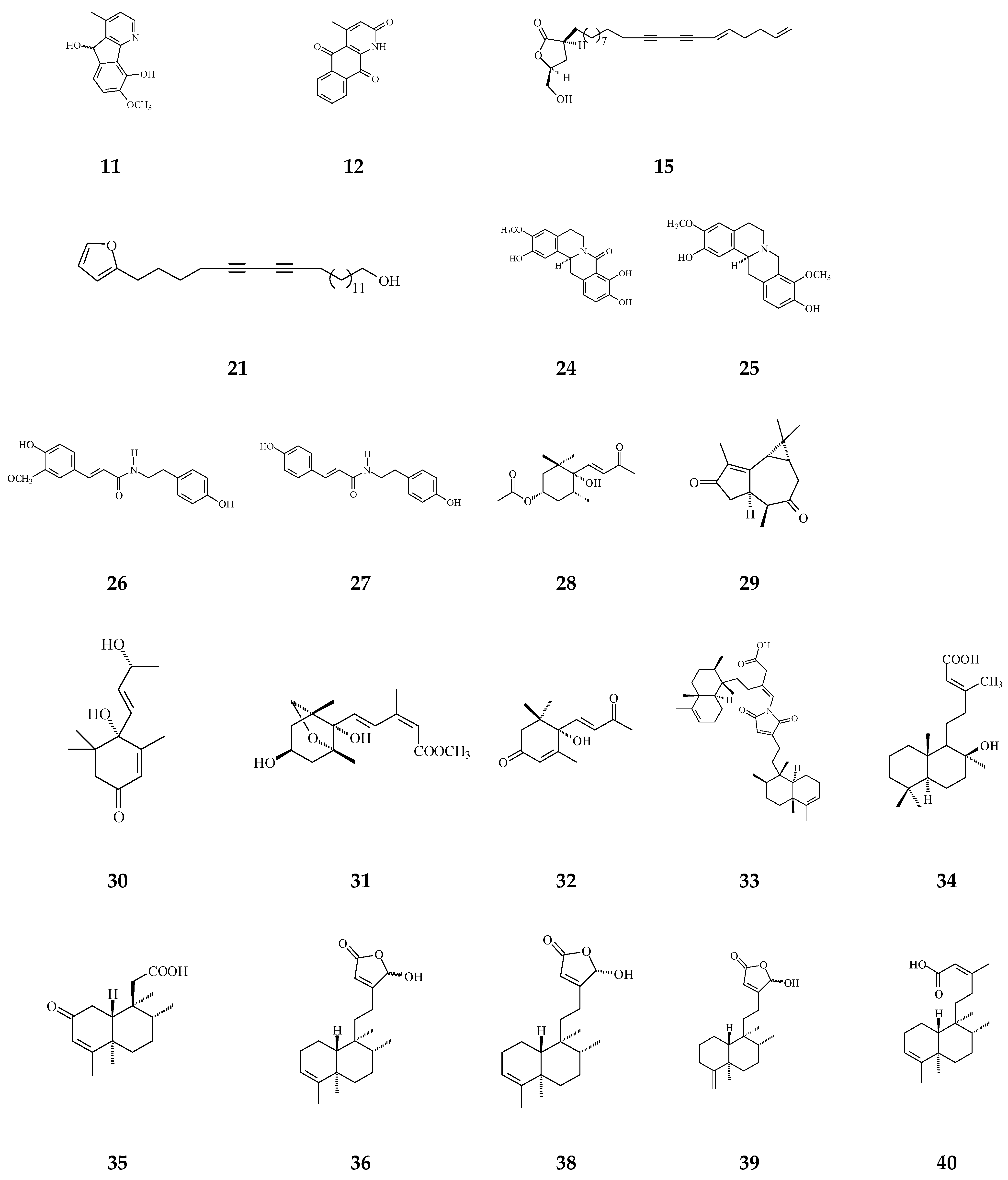

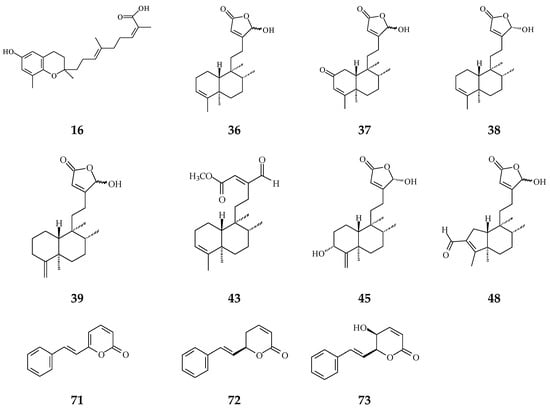

It has been known that certain types of infection are linked to about 13% of all cancer cases [114]. Anti-bacterial and anti-fungal compounds from species of Polyalthia are listed in Table 1 and the structures are shown in Figure 6. Alkaloids and terpenes are origins of anti-microbial agents in Polyalthia (Table 1). Bidebiline E (2), 6, 8-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1-methyl-azafluorenone (10), debilisone B (13), debilisone C (14), debilisone E (15) as well as natural products octadeca-9,11,13-triynoic acid (74) and -humulene have been shown to express potent inhibition against M. tuberculosis (Table 1). Among these compounds, 10 showed the highest potency (MIC 0.78 µg/mL) [75]. Pendulamine A (22) and pendulamine B (23) are classified in 8-oxoprotoberberine, showing broad spectrum inhibitory activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [18]. The MIC in the range of 0.02–20 µg/mL against the tested bacteria [18]. The authors suggested that the anti-bacterial activity is associated with compounds owing a monosubstituted A ring with a hydroxyl group at C-3 [18].

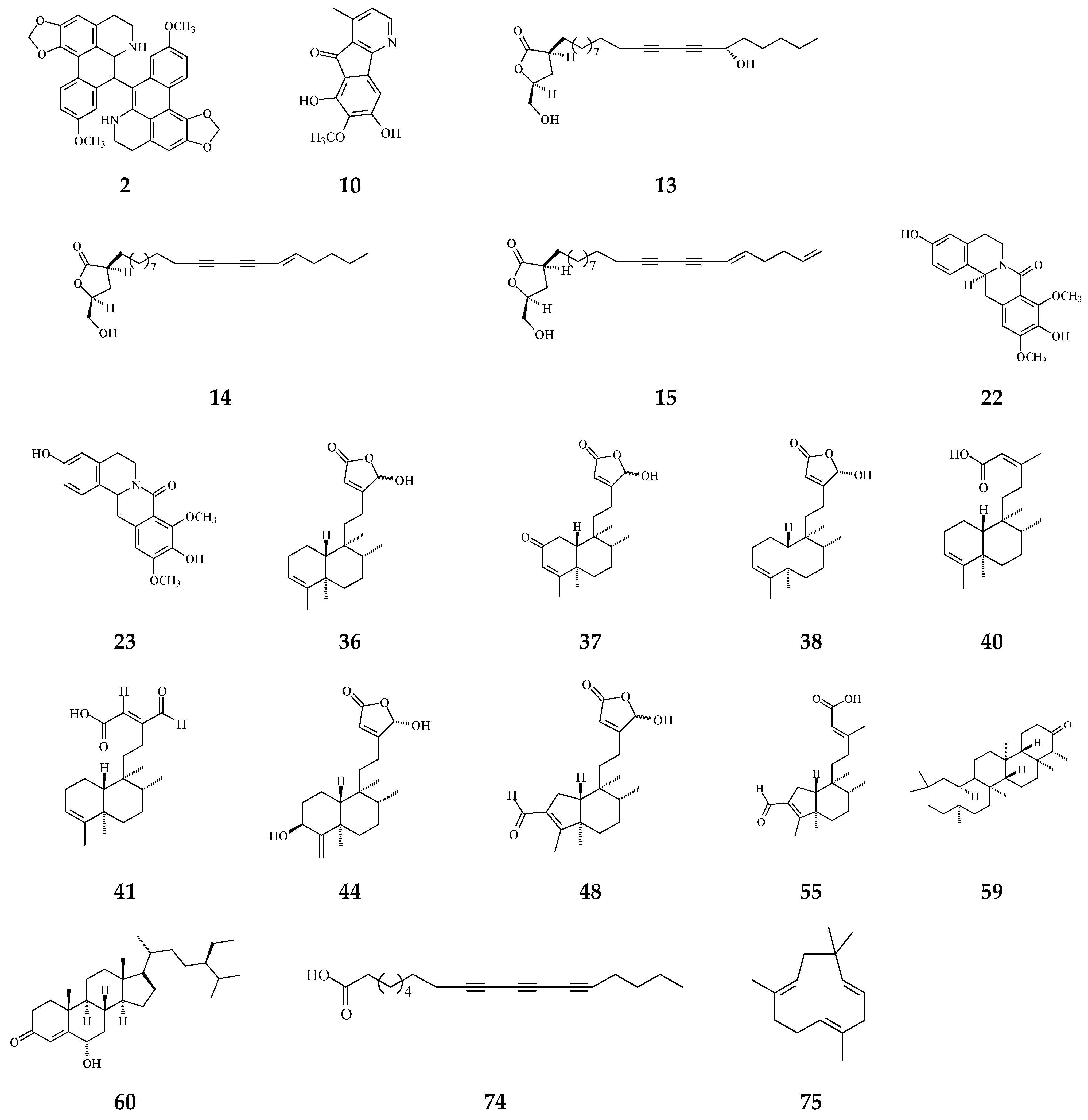

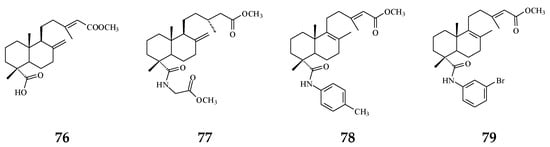

Figure 6.

The phytochemical compounds isolated from species of Polyalthia have anti-bacterial (2, 10, 13–15, 22, 23, 36–38, 40, 41, 44, 48, 55, 59, 60, 74, and 75) and anti-fungal (36 and 41) activities.

The phytochemical compounds of clerodane diterpenoids 36-38, 16-oxocleroda-3,13E-dien-15-oic acid (41), 3β,16α-dihydroxycleroda-4(18),13(14)Z-dien-15,16-olide (44), (4→2)-abeo-16(R&S)-2,13Z-clerodadien-15,16-olide-3-al (48), solidagonal acid (55), friedelin (59), and stigmast-4-ene-6α-ol-3-one (60) also display anti-bacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Table 1). The tertiary chemoprevention of cancer is aimed to prevent cancer recurrence or second tumor/cancer formation in those who have already suffered from curative treatment [2]. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are known to affect or deteriorate cancer patients’ postoperative recovery [114]. Kolavenic acid (40) only kills Gram-positive bacteria [85]. Compound 38 shows the best potency with MIC at 0.78 µg/mL against Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, P. aeryginosa, and S. typhimurium) [20]. On the other hand, 36 and 41 exhibited anti-fungal activity with moderate MIC in the range of 62.5–250 µg/mL [85]. 16-Hydroxycleroda-3,13Z-dien-15,16-olide (36), 38, 59, and 60 displayed better potency against Gram-positive bacteria with MIC in the range of 1.56–7.8 µg/mL (Table 1).

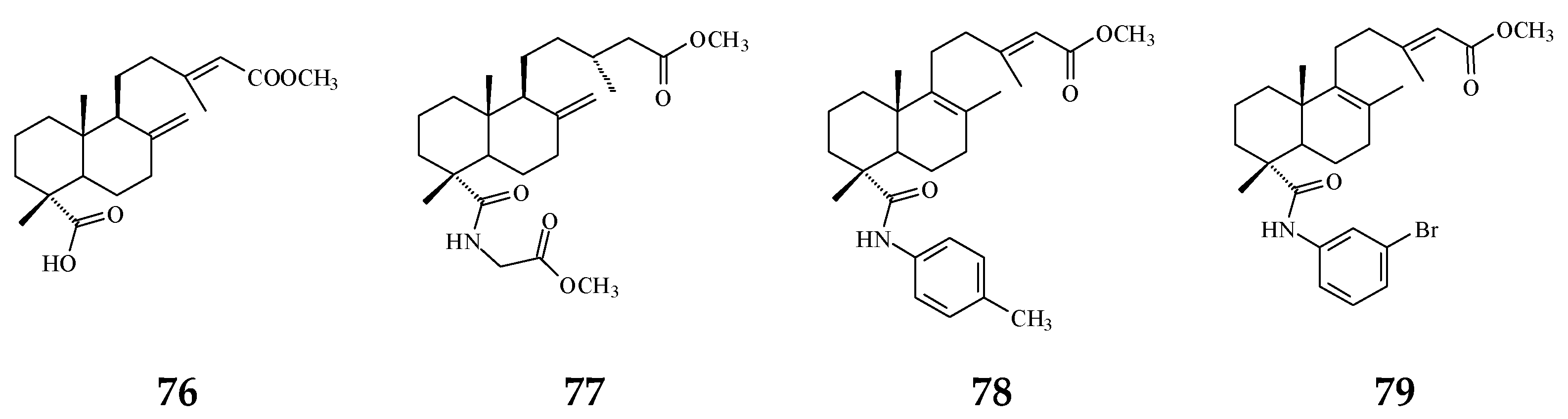

The bacterium Helicobacter pylori infection is responsible for approximately 90% gastric cancer worldwide [115]. Edmond et al. (2020) reported that 36 and (4→2)-abeo-16(R&S)-2,13Z-clerodadien-15,16-olide-3-al (48) are potent agents against H. pylori, and the MIC are 31.25 and 125 µg/mL, respectively, compared with IC50 of the reference drug clarithromycin of 1.95 µg/mL [116]. H. pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis is strongly associated with chronic inflammation [115]. Compound 36 (or 38) and 48 display better activity against histamine release at the concentration of 29.7 and 189.2 µg/mL, compared with diclofenac ‘s IC50 of 17.9 µg/mL [116]. The authors concluded that the weaker activity of 48 are due to (4→2)-abeo migration in it [116]. Study showed that Labdeneamides (77–79) from (4S,9R,10R) methyl 18-carboxy-labda-8,13(E)-diene-15-oate (76), isolated from P. macropoda, also expressed anti-ulcer activity against ethanol/HCl-induced gastric mucosa lesions [30]. The compounds 77–79 (Figure 7) showed the excellent anti-ulcer activity at a single oral dose of 0.1 mg/kgw [30]. H. pylori and gastric mucosa ulcer are the high-risk factors related to gastric cancer [3,115]. Thus, it is highly recommended that the crude extracts and/or CD may be used to possibly treat gastric cancers.

Figure 7.

The synthetic compounds from (4S,9R,10R) methyl 18-carboxy-labda-8,13(E)-dien-15-oate (76) pose anti-ulcer activity (76–79).

8.2. Phytochemical Compounds with Anti-Viral Activity

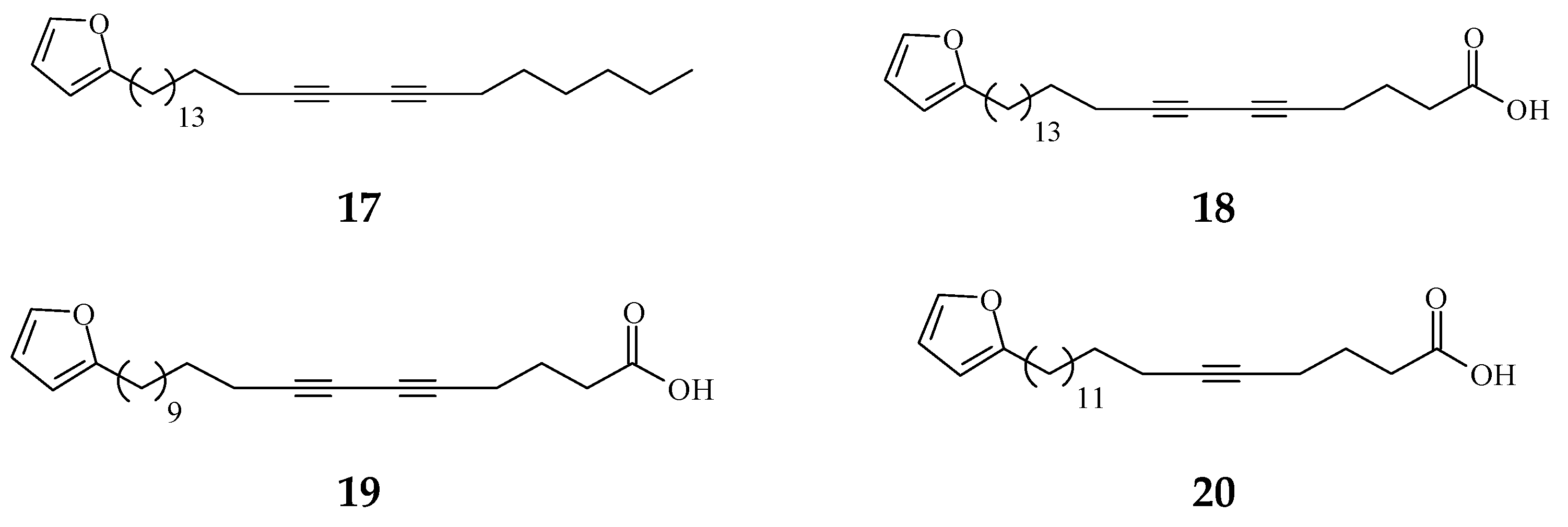

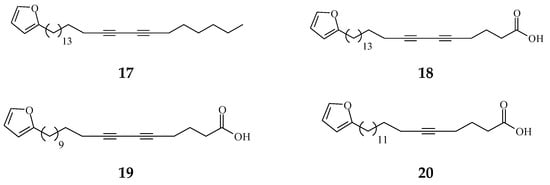

Viruses cause cancer by infection and alteration of genetic codes of host immune cells when the immune system is suppressed or weakened [114]. Three alkaloids and two terpene phytochemical compounds exhibit anti-viral activity (Figure 8). Prenylated benzopyran 1-(2-furyl)pentacosa-16,18-diyne (17) and 23-(2-furyl)tricosa-5,7-diynoic acid (18), terpenes ENT-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid (56) and suberosol (57) inhibit HIV reverse transcriptase activity and viral syncytium. The 2-subsitute furan, 19-(2-furyl)nonadeca-5,7-diynoic acid (19) and 19-(2-furyl)nonadeca-5-ynoic acid (20) also exhibit anti-viral activity against HSV-1 virus.

Figure 8.

The phytochemical compounds isolated from species of Polyalthia exhibit anti-viral activity (17–20, 56, and 57).

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The Polyalthia genus is a resourceful plant, which can be found across the whole island of Taiwan. In fact, numerous kinds of chemical compounds and secondary metabolites from Polyalthia have been studied, showing pharmacological activities that illustrate its values. However, more in vitro and in vivo mechanism investigations would be needed to better understand how it works with the pharmacological effects. Furthermore, the pure components inside Polyalthia with pharmacological effects should be additionally examined to possibly find more effective substances. Certainly, for the known pure compounds, such as 16-hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-16,15-olide (36) and/or 16α-hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-16,15-olide (38), it should be worth further investigating in detail in vitro and in vivo mechanisms that can conceivably be used as drugs for chemoprevention.

Author Contributions

Y.-C.C. (Yung-Chia Chen), Y.-C.C. (Yi-Chen Chia) and B.-M.H. wrote the manuscript. Y.-C.C. (Yung-Chia Chen) shot photos of P. longifolia. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the scientific truth in ensuring that the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 109-2635-B-037-001 to YCC and MOST 110-2314-B-006-025-MY3 to BMH).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

CD: 16-hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-16,15-olide.

References

- Tsao, A.S.; Kim, E.S.; Hong, W.K. Chemoprevention of cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2004, 54, 150–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, K.J.; Li, G. An overview of cancer prevention: Chemoprevention and immunoprevention. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 25, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greten, F.R.; Grivennikov, S.I. Inflammation and cancer: Triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 2019, 51, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surh, Y.J. Cancer chemoprevention with dietary phytochemicals. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, F.H.M.; Oliveira, J.S.; Sartorelli, V.O.B.; Montor, W.R. Cancer chemoprevention: Classic and epigenetic mechanisms inhibiting tumorigenesis. What have we learned so far? Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, N.; Afaq, F.; Mukhtar, H. Cancer chemoprevention through dietary antioxidants: Progress and promise. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2008, 10, 475–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatrou, L.; Erkens, R.J.; Richardson, J.E.; Saunders, R.K.; Fay, M. The natural history of Annonaceae. Bot J. Linn. Soc. 2012, 169, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, T.H.; Wang, M.J.; Chen, P.Y.; Wu, T.Y.; Wen, W.C.; Tsai, F.Y.; Lee, C.K. Constituents of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1960–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jothy, S.L.; Yeng, C.; Sasidharan, S. Chromatographic and spectral fingerprinting of Polyalthia longifolia, a source of phytochemicals. Bioresources 2013, 8, 5102–5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jothy, S.L.; Saito, T.; Kanwar, J.R.; Chen, Y.; Aziz, A.; Yin-Hui, L.; Sasidharan, S. Radioprotective activity of Polyalthia longifolia standardized extract against X-ray radiation injury in mice. Phys. Med. 2016, 32, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayarathna, S.; Chen, Y.; Kanwar, J.R.; Sasidharan, S. Standardized Polyalthia longifolia leaf extract (PLME) inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis: The anti-cancer study with various microscopy methods. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chang, F.R.; Shih, Y.C.; Hsieh, T.J.; Chia, Y.C.; Tseng, H.Y.; Chen, H.C.; Chen, S.J.; Hsu, M.C.; Wu, Y.C. Cytotoxic constituents of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1475–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, S.; Dave, R.; Kaneria, M.; Shukla, V. Acute oral toxicity of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula leaf extract in Wistar albino rats. Pharm. Biol. 2012, 50, 1408–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jothy, S.L.; Chen, Y.; Kanwar, J.R.; Sasidharan, S. Evaluation of the genotoxic potential against H2O2-radical-mediated DNA damage and acute oral toxicity of standardized extract of Polyalthia longifolia leaf. Evid Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 2013, 925380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rates, S.M.K. Plants as source of drugs. Toxicon 2001, 39, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizi, S.; Khan, R.A.; Azher, S.; Khan, S.A.; Tauseef, S.; Ahmad, A. New antimicrobial alkaloids from the roots of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula. Planta Med. 2003, 69, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanokmedhakul, S.; Kanokmedhakul, K.; Lekphrom, R. Bioactive constituents of the roots of Polyalthia cerasoides. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 1536–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marthanda Murthy, M.; Subramanyam, M.; Hima Bindu, M.; Annapurna, J. Antimicrobial activity of clerodane diterpenoids from Polyalthia longifolia seeds. Fitoterapia 2005, 76, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.K.; Chand, H.R.; John, J.; Deshpande, M.V. Clerodane type diterpene as a novel antifungal agent from Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 94, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanokmedhakul, S.; Kanokmedhakul, K.; Kantikeaw, I.; Phonkerd, N. 2-substituted furans from the roots of Polyalthia evecta. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Sun, N.J.; Kashiwada, Y.; Sun, L.; Snider, J.V.; Cosentino, L.M.; Lee, K.H. Anti-AIDS agents, 9. Suberosol, a new C31 lanostane-type triterpene and anti-HIV principle from Polyalthia suberosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 1130–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, P.; Sashidhara, K.V.; Singh, S.P.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, R.; Chaudhaery, S.S.; Gupta, S.S.; Majumder, H.K.; Saxena, A.K.; Dube, A. 16alpha-Hydroxycleroda-3,13 (14)Z-dien-15,16-olide from Polyalthia longifolia: A safe and orally active antileishmanial agent. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 159, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gbedema, S.Y.; Bayor, M.T.; Annan, K.; Wright, C.W. Clerodane diterpenes from Polyalthia longifolia (Sonn) Thw. var. pendula: Potential antimalarial agents for drug resistant Plasmodium falciparum infection. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 169, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngantchou, I.; Nyasse, B.; Denier, C.; Blonski, C.; Hannaert, V.; Schneider, B. Antitrypanosomal alkaloids from Polyalthia suaveolens (Annonaceae): Their effects on three selected glycolytic enzymes of Trypanosoma brucei. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 3495–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.R.; Hwang, T.L.; Yang, Y.L.; Li, C.E.; Wu, C.C.; Issa, H.H.; Hsieh, W.B.; Wu, Y.C. Anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic diterpenes from formosan Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 1344–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, A.; Collado, A.; Barrachina, I.; Marques, P.; El Aouad, N.; Franck, X.; Garibotto, F.; Dacquet, C.; Caignard, D.H.; Suvire, F.D.; et al. Polycerasoidol, a natural prenylated benzopyran with a dual PPARalpha/PPARgamma agonist activity and anti-inflammatory effect. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1802–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Vu, T.Y.; Chandi, V.; Polimati, H.; Tatipamula, V.B. Dual COX and 5-LOX inhibition by clerodane diterpenes from seeds of Polyalthia longifolia (Sonn.) Thwaites. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olate, V.R.; Pertino, M.W.; Theoduloz, C.; Yesilada, E.; Monsalve, F.; Gonzalez, P.; Droguett, D.; Richomme, P.; Hadi, A.H.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G. New gastroprotective labdeneamides from (4S,9R,10R) methyl 18-carboxy-labda-8,13(E)-diene-15-oate. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.C.; Duh, C.Y.; Wang, S.K.; Chen, K.S.; Yang, T.H. Two new natural azafluorene alkaloids and a cytotoxic aporphine alkaloid from Polyalthia longifolia. J. Nat. Prod. 1990, 53, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.Y.; Guo, K.Y.; Lv, D.J.; Mei, R.Q.; Zhang, M.D. Terpenes isolated from Polyalthia simiarum and their cytotoxic activities. Fitoterapia 2020, 147, 104734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Lee, I.S.; Chai, H.B.; Zaw, K.; Farnsworth, N.R.; Soejarto, D.D.; Cordell, G.A.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Kinghorn, A.D. Cytotoxic clerodane diterpenes from Polyalthia barnesii. Phytochem 1994, 37, 1659–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, V.; Sivalingam, K.S.; Viswanadha, V.P.; Weng, C.F. 16-hydroxy-cleroda-3,13-dien-16,15-olide induced glioma cell autophagy via ROS generation and activation of p38 MAPK and ERK-1/2. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 45, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afolabi, S.O.; Olorundare, O.E.; Babatunde, A.; Albrecht, R.M.; Koketsu, M.; Syed, D.N.; Mukhtar, H. Polyalthia longifolia extract triggers ER stress in prostate cancer cells concomitant with induction of apoptosis: Insights from in vitro and in vivo studies. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 6726312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.F.; Lin, S.R.; Tseng, F.J.; Huang, Y.C.; Tsai, M.J.; Fu, Y.S.; Weng, C.F. The autophagic inhibition oral squamous cell carcinoma cancer growth of 16-hydroxy-cleroda-3,14-dine-15,16-olide. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 78379–78396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paarakh, P.M.; Khosa, R. Phytoconstituents from the genus Polyalthia—A review. J. Pharm. Res. 2009, 2, 594–605. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.J.; Jalil, J.; Attiq, A.; Hui, C.C.; Zakaria, N.A. The medicinal uses, toxicities and anti-inflammatory activity of Polyalthia species (Annonaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 229, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.S.; Luo, Y.P.; Wang, J.; He, M.X.; Zhong, M.G.; Li, Y.; Song, X.P. (+)-rumphiin and polyalthurea, new compounds from the stems of Polyalthia rumphii. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 1427–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faizi, S.; Mughal, N.R.; Khan, R.A.; Khan, S.A.; Ahmad, A.; Bibi, N.; Ahmed, S.A. Evaluation of the antimicrobial property of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula: Isolation of a lactone as the active antibacterial agent from the ethanol extract of the stem. Phytother. Res. 2003, 17, 1177–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Singh, S.P.; Pandey, A.R.; Ansari, A.; Ahmad, S.; Sashidhara, K.V.; Tamrakar, A.K. Flavonoids from Polyalthia longifolia prevents advanced glycation end products formation and protein oxidation aligned with fructose-induced protein glycation. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, G.M.; Nalawade, V.V.; Mukadam, A.S.; Chaskar, P.K.; Zine, S.P.; Somani, R.R.; Une, H.D. Elucidation of flavonoids from Carissa congesta, Polyalthia longifolia, and Benincasa hispida plant extracts by hyphenated technique of liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy. Pharmacogn. Res. 2016, 8, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thiyagarajan, V.; Lin, S.X.; Lee, C.H.; Weng, C.F. A focal adhesion kinase inhibitor 16-hydroxy-cleroda-3,13-dien-16,15-olide incorporated into enteric-coated nanoparticles for controlled anti-glioma drug delivery. Colloids Surf. B 2016, 141, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Lee, W.C.; Huang, B.M.; Chia, Y.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.C. 16-Hydroxycleroda-3, 13-dien-15, 16-olide inhibits the proliferation and induces mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis through Akt, mTOR, and MEK-ERK pathways in human renal carcinoma cells. Phytomedicine 2017, 36, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Lee, C.C.; Chan, W.L.; Chang, W.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Chang, J.G. 16-Hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-15,16-olide deregulates PI3K and Aurora B activities that involve in cancer cell apoptosis. Toxicology 2011, 285, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sashidhara, K.V.; Singh, S.P.; Srivastava, A.; Puri, A.; Chhonker, Y.S.; Bhatta, R.S.; Shah, P.; Siddiqi, M.I. Discovery of a new class of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor from Polyalthia longifolia as potential lipid lowering agent. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 5206–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, M.; Shankar, K.; Varshney, S.; Rajan, S.; Singh, S.P.; Jagdale, P.; Puri, A.; Chaudhari, B.P.; Sashidhara, K.V.; Gaikwad, A.N. A clerodane diterpene inhibit adipogenesis by cell cycle arrest and ameliorate obesity in C57BL/6 mice. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2015, 399, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Tiwari, N.; Gupta, P.; Verma, S.; Pal, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Darokar, M.P. A clerodane diterpene from Polyalthia longifolia as a modifying agent of the resistance of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.K.; Verma, S.; Pal, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Srivastava, P.K.; Darokar, M.P. In vivo efficacy and synergistic interaction of 16alpha-hydroxycleroda-3, 13 (14) Z-dien-15, 16-olide, a clerodane diterpene from Polyalthia longifolia against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9121–9131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Baravalia, Y.; Kaneria, M. Protective effect of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula leaves on ethanol and ethanol/HCl induced ulcer in rats and its antimicrobial potency. Asian Pac. J. Trop Med. 2011, 4, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, P.K.; Lin, S.R.; Riyaphan, J.; Fu, Y.S.; Weng, C.F. Polyalthia clerodane diterpene potentiates hypoglycemia via inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase 4. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.C.; Wang, P.Y.; Huang, B.M.; Chen, Y.J.; Lee, W.C.; Chen, Y.C. 16-Hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-15,16-olide induces apoptosis in human bladder cancer cells through cell cycle arrest, mitochondria ROS overproduction, and inactivation of EGFR-related signalling pathways. Molecules 2020, 25, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, V.; Lin, S.H.; Chia, Y.C.; Weng, C.F. A novel inhibitor, 16-hydroxy-cleroda-3,13-dien-16,15-olide, blocks the autophosphorylation site of focal adhesion kinase (Y397) by molecular docking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 4091–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sashidhara, K.V.; Singh, S.P.; Srivastava, A.; Puri, A. Identification of the antioxidant principles of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula using TEAC assay. Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 25, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothy, S.L.; Aziz, A.; Chen, Y.; Sasidharan, S. Antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of Polyalthia longifolia and Cassia spectabilis leaves against paracetamol-induced liver Injury. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 2012, 561284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.X.; Liang, G.; Chai, W.M.; Feng, H.L.; Zhou, H.T.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Q.X. Antioxidant and antityrosinase proanthocyanidins from Polyalthia longifolia leaves. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2014, 118, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.; Rahman, M.S.; Chowdhury, A.M.; Hasan, C.M.; Rashid, M.A. An unusual bisnor-clerodane diterpenoid from Polyalthia simiarum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manjula, S.N.; Kenganora, M.; Parihar, V.K.; Kumar, S.; Nayak, P.G.; Kumar, N.; Ranganath Pai, K.S.; Rao, C.M. Antitumor and antioxidant activity of Polyalthia longifolia stem bark ethanol extract. Pharm. Biol. 2010, 48, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oyeyemi, A.O.; Oseni, O.A.; Babatunde, A.O.; Molehin, O.R. Modulatory effect of Polyalthia longifolia leaves against cadmium-induced oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity in rats. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.T.; Hsu, Y.Y.; Chang, F.R.; Wu, Y.C.; Lo, Y.C. 6-Hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-15,16-olide protects neuronal cells from lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity through the inhibition of microglia-mediated inflammation. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 2977–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.P. Inflammation and its role in regeneration and repair. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.H.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Chen, C.J.; Ng, L.T.; Chou, L.C.; Huang, L.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Kuo, S.C.; El-Shazly, M.; Wu, Y.C.; et al. Three new clerodane diterpenes from Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula. Molecules 2014, 19, 2049–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liou, J.R.; Wu, T.Y.; Thang, T.D.; Hwang, T.L.; Wu, C.C.; Cheng, Y.B.; Chiang, M.Y.; Lan, Y.H.; El-Shazly, M.; Wu, S.L.; et al. Bioactive 6S-styryllactone constituents of Polyalthia parviflora. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2626–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Bobinski, R.; Dutka, M. Self-regulation of the inflammatory response by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Inflamm Res. 2019, 68, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, H.S.; Tan, W.R.; Low, Z.S.; Marvalim, C.; Lee, J.Y.H.; Tan, N.S. Exploration and development of PPAR modulators in health and disease: An update of clinical evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henry, R.R.; Lincoff, A.M.; Mudaliar, S.; Rabbia, M.; Chognot, C.; Herz, M. Effect of the dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha/gamma agonist aleglitazar on risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes (SYNCHRONY): A phase II, randomised, dose-ranging study. Lancet 2009, 374, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliora, C.; Kyriazis, I.D.; Oka, S.I.; Lieu, M.J.; Yue, Y.; Area-Gomez, E.; Pol, C.J.; Tian, Y.; Mizushima, W.; Chin, A.; et al. Dual peroxisome-proliferator-activated-receptor-alpha/gamma activation inhibits SIRT1-PGC1alpha axis and causes cardiac dysfunction. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e129556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cadavid, A.P. Aspirin: The mechanism of action revisited in the context of pregnancy Complications. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Annan, K.; Dickson, R.; Sarpong, K.; Asare, C.; Amponsah, K.; Woode, E. Antipyretic activity of Polyalthia longifolia Benth. & Hook. F. var. pendula (Annonaceae), on lipopolysaccharide-induced fever in rats. J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2013, 2, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.H.; Lin, S.R.; Tseng, F.J.; Tsai, M.J.; Lue, S.I.; Chia, Y.C.; Woon, M.; Fu, Y.S.; Weng, C.F. Clerodane diterpene ameliorates inflammatory bowel disease and potentiates cell apoptosis of colorectal cancer. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shono, T.; Ishikawa, N.; Toume, K.; Arai, M.A.; Masu, H.; Koyano, T.; Kowithayakorn, T.; Ishibashi, M. Cerasoidine, a bis-aporphine alkaloid isolated from Polyalthia cerasoides during screening for Wnt signal inhibitors. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2083–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, R.; Yu, D. Aporphine alkaloids from branches and leaves of Polyalthia nemoralis. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2009, 34, 2343–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Pumsalid, K.; Thaisuchat, H.; Loetchutinat, C.; Nuntasaen, N.; Meepowpan, P.; Pompimon, W. A new azafluorenone from the roots of Polyalthia cerasoides and its biological activity. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1931–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Banjerdpongchai, R.; Khaw-On, P.; Ristee, C.; Pompimon, W. 6,8-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1-methyl-azafluorenone induces caspase-8- and -9-mediated apoptosis in human cancer cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 2637–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, G.; Han, C.; Wang, J. Isolation and crystal structure of marcanine A from Polyalthia plagioneura. Molecules 2010, 15, 6349–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panthama, N.; Kanokmedhakul, S.; Kanokmedhakul, K. Polyacetylenes from the roots of Polyalthia debilis. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1366–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonpangrak, S.; Cherdtrakulkiat, R.; Pingaew, R.; Manam, P.; Prachayasittikul, S.; Ruchirawat, S.; Prachayasittikul, V. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic acetogenin from Polyalthia debilis. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 5, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tuchinda, P.; Pohmakotr, M.; Reutrakul, V.; Thanyachareon, W.; Sophasan, S.; Yoosook, C.; Santisuk, T.; Pezzuto, J.M. 2-substituted furans from Polyalthia suberosa. Planta Med. 2001, 67, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.J.; Zheng, C.J.; Wang, L.K.; Han, C.R.; Song, X.P.; Chen, G.Y.; Zhou, X.M.; Wu, S.Y.; Li, X.B.; Bai, M.; et al. One new berberine from the branches and leaves of Polyalthia obliqua Hook.f. & Thomson. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 2285–2290. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.X.; Zhuo, M.Y.; Li, X.B.; Fu, Y.H.; Chen, G.Y.; Song, X.P.; Han, C.R.; Song, X.M.; Fan, Q.J. A new norsesquiterpene from the roots of Polyalthia laui. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sashidhara, K.V.; Singh, S.P.; Kant, R.; Maulik, P.R.; Sarkar, J.; Kanojiya, S.; Ravi Kumar, K. Cytotoxic cycloartane triterpene and rare isomeric bisclerodane diterpenes from the leaves of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 5767–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, S.; Olorundare, O.; Ninomiya, M.; Babatunde, A.; Mukhtar, H.; Koketsu, M. Comparative antileukemic activity of a tetranorditerpene isolated from Polyalthia longifolia leaves and the derivative against human leukemia HL-60 cells. J. Oleo Sci. 2017, 66, 1169–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Faizi, S.; Khan, R.A.; Mughal, N.R.; Malik, M.S.; Sajjadi, K.E.; Ahmad, A. Antimicrobial activity of various parts of Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula: Isolation of active principles from the leaves and the berries. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, D.P.; Ninomiya, M.; Efdi, M.; Santoni, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Tanaka, K.; Koketsu, M. Clerodane diterpenes isolated from Polyalthia longifolia induce apoptosis in human leukemia HL-60 cells. J. Oleo Sci. 2013, 62, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, G.X.; Jung, J.H.; Smith, D.L.; Wood, K.V.; McLaughlin, J.L. Cytotoxic clerodane diterpenes from Polyalthia longifolia. Planta Med. 1991, 57, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Peng, W.; Yang, B.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y. A new sesquiterpenoid from Polyalthia petelotii. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sashidhara, K.V.; Singh, S.P.; Shukla, P.K. Antimicrobial evaluation of clerodane diterpenes from Polyalthia longifolia var. pendula. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sashidhara, K.V.; Singh, S.P.; Sarkar, J.; Sinha, S. Cytotoxic clerodane diterpenoids from the leaves of Polyalthia longifolia. Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 24, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.X.; Fu, Y.H.; Chen, G.Y.; Song, X.P.; Han, C.R.; Li, X.B.; Song, X.M.; Wu, A.Z.; Chen, S.C. New clerodane diterpenoids from the roots of Polyalthia laui. Fitoterapia 2016, 111, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saepou, S.; Pohmakotr, M.; Reutrakul, V.; Yoosook, C.; Kasisit, J.; Napaswad, C.; Tuchinda, P. Anti-HIV-1 diterpenoids from leaves and twigs of Polyalthia sclerophylla. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.H.; Ji, M.H.; Shu, H.M.; Chen, G.Y.; Song, X.P.; Wang, J. Chemical constituents from the roots of Polyalthia obliqua. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2012, 10, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suedee, A.; Mondranondra, I.O.; Kijjoa, A.; Pinto, M.; Nazareth, N.; Nascimento, M.S.; Silva, A.M.S.; Herz, W. Constituents of Polyalthia jucunda and their cytotoxic effect on human cancer cell lines. Pharm. Biol. 2007, 45, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.K.; Zheng, C.J.; Li, X.B.; Chen, G.Y.; Han, C.R.; Chen, W.H.; Song, X.P. Two new lanostane triterpenoids from the branches and leaves of Polyalthia oblique. Molecules 2014, 19, 7621–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tuchinda, P.; Munyoo, B.; Pohmakotr, M.; Thinapong, P.; Sophasan, S.; Santisuk, T.; Reutrakul, V. Cytotoxic styryl-lactones from the leaves and twigs of Polyalthia crassa. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 1728–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, Y.S.; Mahadevan, K.M.; Manjunatha, H.; Satyanarayana, N.D. Antiproliferative, apoptotic and antimutagenic activity of isolated compounds from Polyalthia cerasoides seeds. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupachandra, S.; Sarada, D.V. Anti-proliferative and apoptotic properties of a peptide from the seeds of Polyalthia longifolia against human cancer cell lines. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 51, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.H.; Lee, C.C.; Chang, F.R.; Chang, W.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Chang, J.G. 16-hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-15,16-olide regulates the expression of histone-modifying enzymes PRC2 complex and induces apoptosis in CML K562 cells. Life Sci. 2011, 89, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Huang, B.M.; Lee, W.C.; Chen, Y.C. 16-Hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-15,16-olide induces anoikis in human renal cell carcinoma cells: Involvement of focal adhesion disassembly and signaling. Oncol. Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 7679–7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jasek-Gajda, E.; Jurkowska, H.; Jasinska, M.; Lis, G.J. Targeting the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways affects NRF2, Trx and GSH antioxidant systems in leukemia cells. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.; Lopez, J.M. Understanding MAPK signaling pathways in apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y.; Nikulenkov, F.; Zawacka-Pankau, J.; Li, H.; Gabdoulline, R.; Xu, J.; Eriksson, S.; Hedstrom, E.; Issaeva, N.; Kel, A.; et al. ROS-dependent activation of JNK converts p53 into an efficient inhibitor of oncogenes leading to robust apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Gu, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Dong, X.; Liu, C.; Hu, X.; Ji, X.; Huang, S.; et al. Celastrol ameliorates Cd-induced neuronal apoptosis by targeting NOX2-derived ROS-dependent PP5-JNK signaling pathway. J. Neurochem. 2017, 141, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, T.; Li, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, R.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Shao, C. Isoliensinine induces apoptosis in triple-negative human breast cancer cells through ROS generation and p38 MAPK/JNK activation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shanmugapriya; Vijayarathna, S.; Sasidharan, S. Functional Validation of DownRegulated MicroRNAs in HeLa Cells Treated with Polyalthia longifolia Leaf Extract Using Different Microscopic Approaches: A Morphological Alteration-Based Validation. Microsc. Microanal. 2019, 25, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugapriya; Sasidharan, S. Functional analysis of down-regulated miRNA-221-5p in HeLa cell treated with polyphenol-rich Polyalthia longifolia as regulators of apoptotic HeLa cell death. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, L.F.R.; MacRae, I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupaimoole, R.; Slack, F.J. MicroRNA therapeutics: Towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, J.; van Leeuwen, J.E.; Elbaz, M.; Branchard, E.; Penn, L.Z. Statins as anticancer agents in the era of precision medicine. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 5791–5800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velmurugan, B.K.; Wang, P.C.; Weng, C.F. 16-Hydroxycleroda-3,13-dien-15,16-olide and N-methyl-actinodaphine potentiate tamoxifen-induced cell death in breast cancer. Molecules 2018, 23, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hussain, S.S.; Rafi, K.; Faizi, S.; Razzak, Z.A.; Simjee, S.U. A novel, semi-synthetic diterpenoid 16(R and S)-phenylamino-cleroda-3,13(14), Z-dien-15,16 olide (PGEA-AN) inhibits the growth and cell survival of human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y by modulating P53 pathway. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2018, 449, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martel, C.; Georges, D.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Clifford, G.M. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moss, S.F. The clinical evidence linking Helicobacter pylori to gastric cancer. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 3, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edmond, M.P.; Mostafa, N.M.; El-Shazly, M.; Singab, A.N.B. Two clerodane diterpenes isolated from Polyalthia longifolia leaves: Comparative structural features, anti-histaminic and anti-Helicobacter pylori activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).