Xanthurenic Acid in the Shell Purple Patterns of Crassostrea gigas: First Evidence of an Ommochrome Metabolite in a Mollusk Shell

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

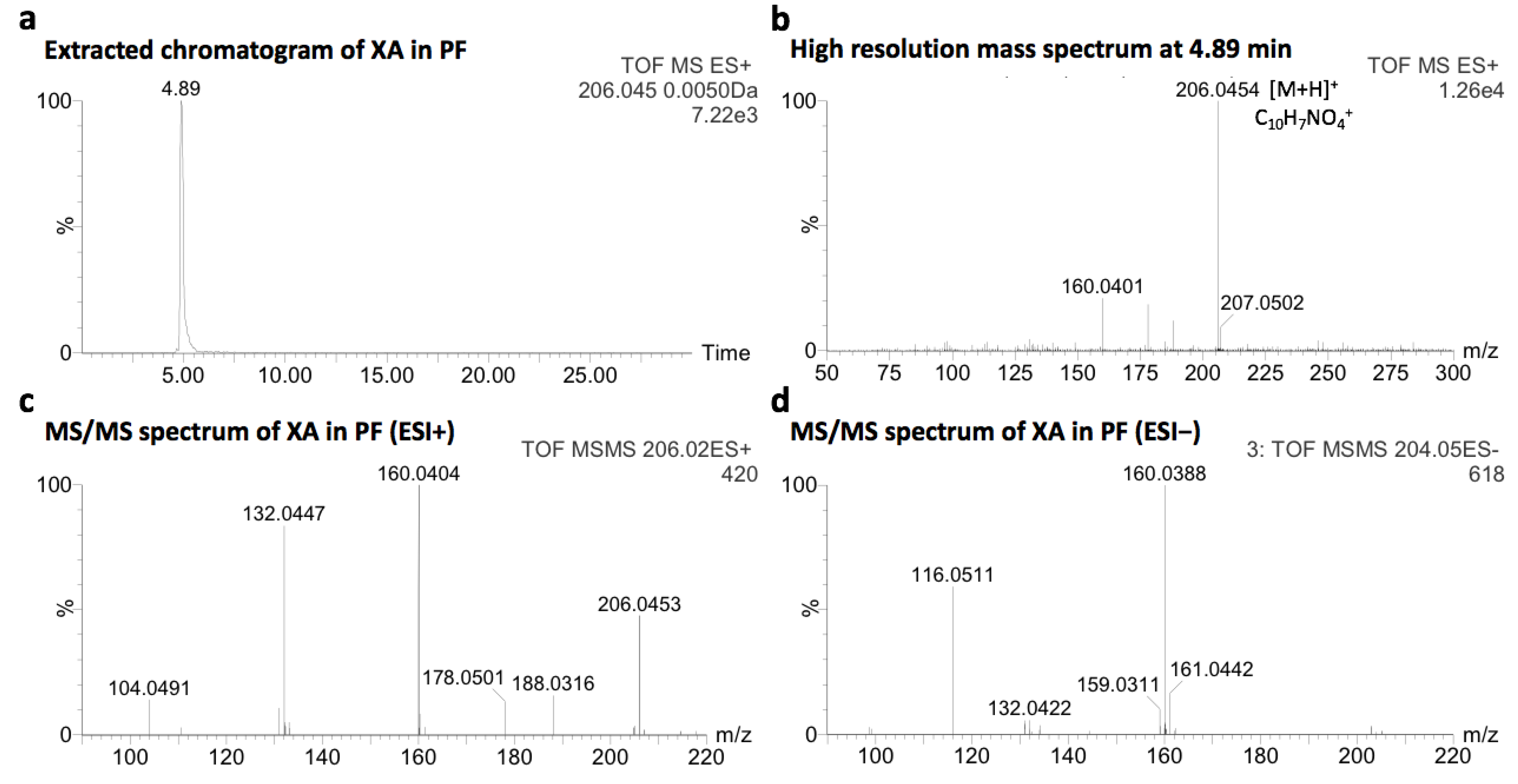

2.1. Identification of Xanthurenic Acid

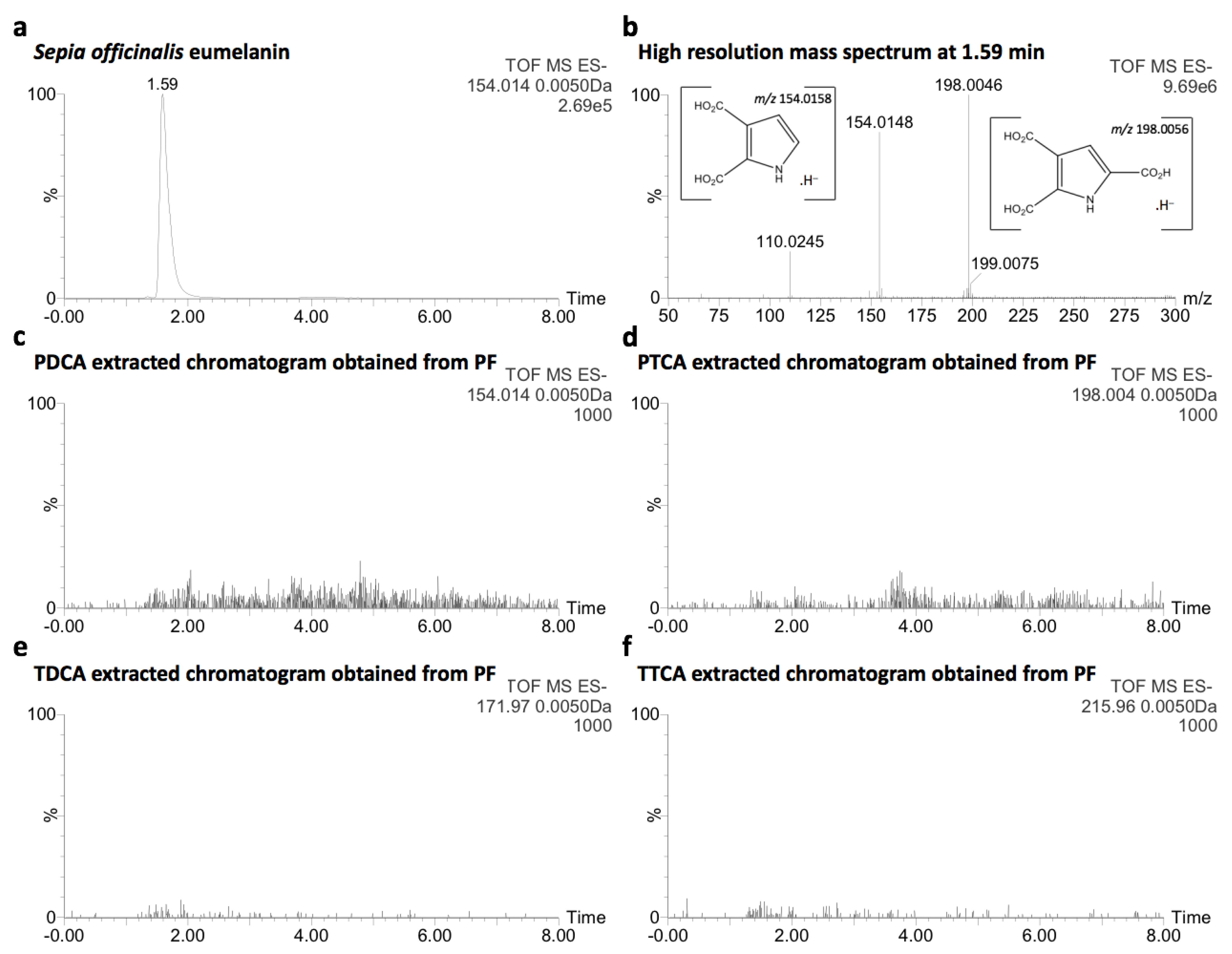

2.2. Characterization of the Purple Fraction of Acid-Soluble Pigments

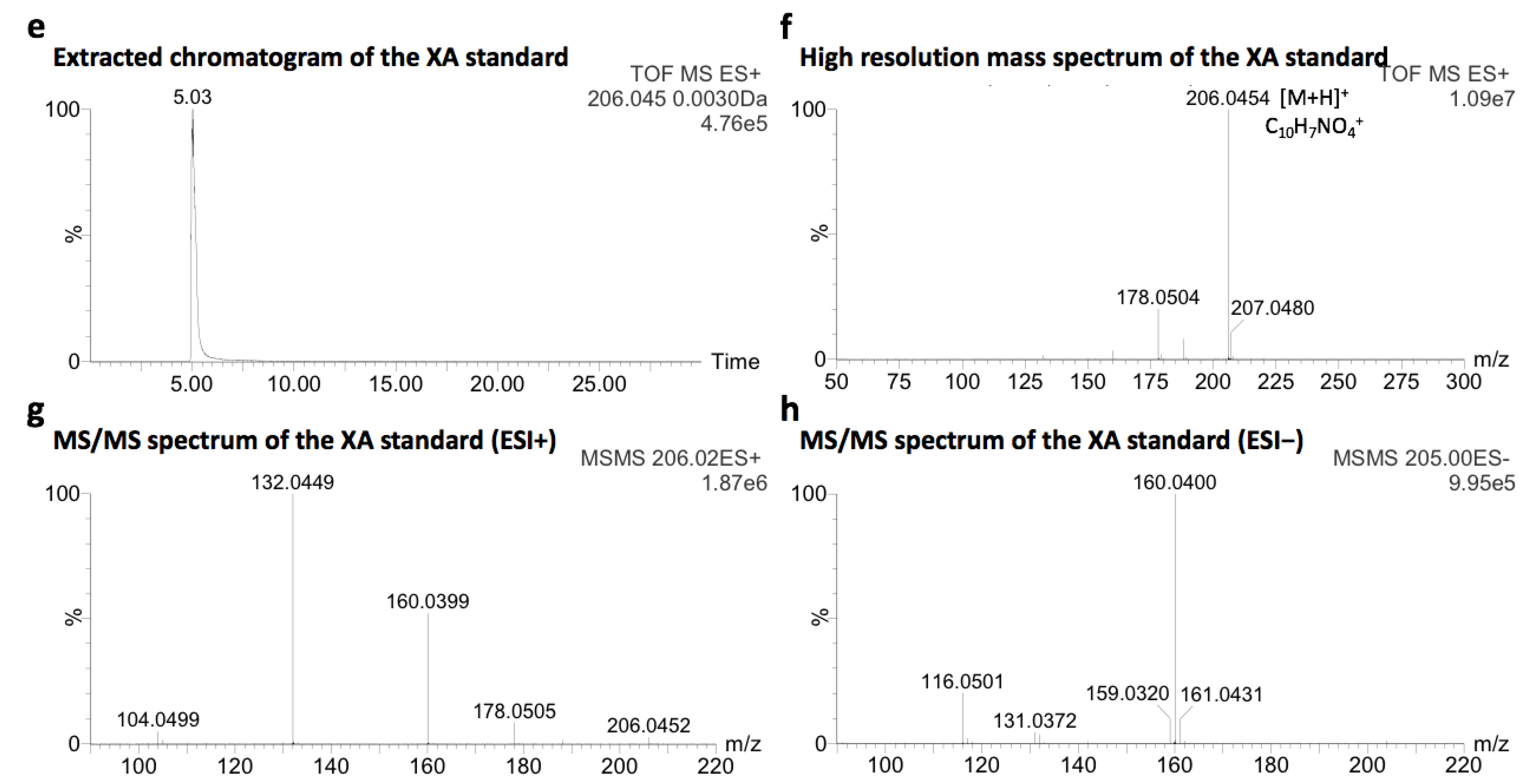

2.3. Comparative Analysis with Natural Melanin

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Shell Fragments

4.2. Identification of XA in PF

4.3. Characterization of PF

4.4. Comparative Analysis with Natural Eumelanin

4.5. Chemicals

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

Abbreviations

| 3-HA | 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid |

| 3-HK | 3-hydroxykynurenine |

| ESI− | electrospray negative ionization mode |

| ESI+ | electrospray positive ionization mode |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| HMASP | high molecular weight acid-soluble pigments |

| IR | infrared |

| MS/MS | tandem mass spectrometry |

| PDCA | pyrrole-2,3-dicarboxylic acid |

| PF | purple fraction |

| PTCA | pyrrole-2,3,5-tricarboxylic acid |

| TDCA | thiazole-4,5-dicarboxylic acid |

| TFA | trifluoroacetic acid |

| TTCA | thiazole-2,4,5-tricarboxylic acid |

| UPLC-MS | liquid chromatography mass spectrometry |

| UPLC-MS/MS | liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry |

| XA | xanthurenic acid |

References

- Williams, S.T. Molluscan Shell Colour. Biol. Rev. 2017, 92, 1039–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comfort, A. Acid-Soluble Pigments of Shells. 1. The Distribution of Porphyrin Fluorescence in Molluscan Shells. Biochem. J. 1949, 44, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williams, S.T.; Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K.; Goral, T.; Edwards, N.P.; Wogelius, R.A.; Henkel, T.; de Oliveira, L.F.C.; Maia, L.F.; Strekopytov, S.; et al. Identification of Shell Colour Pigments in Marine Snails Clanculus pharaonius and C. margaritarius (Trochoidea; Gastropoda). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stenger, P.-L.; Ky, C.-L.; Reisser, C.; Duboisset, J.; Dicko, H.; Durand, P.; Quintric, L.; Planes, S.; Vidal-Dupiol, J. Molecular Pathways and Pigments Underlying the Colors of the Pearl Oyster Pinctada margaritifera Var. cumingii (Linnaeus 1758). Genes 2021, 12, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affenzeller, S.; Wolkenstein, K.; Frauendorf, H.; Jackson, D.J. Eumelanin and Pheomelanin Pigmentation in Mollusc Shells May Be Less Common than Expected: Insights from Mass Spectrometry. Front. Zool. 2019, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hao, S.; Hou, X.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Extraction and Identification of the Pigment in the Adductor Muscle Scar of Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnard, M.; Cantel, S.; Boury, B.; Parrot, I. Chemical Evidence of Rare Porphyrins in Purple Shells of Crassostrea gigas Oyster. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Li, Q.; Yu, H.; Du, S. Identification and Characterization of Key Haem Pathway Genes Associated with the Synthesis of Porphyrin in Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea gigas). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 255, 110595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Li, Q.; Yu, H.; Kong, L.; Du, S. Transcriptional Profiling of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Mantle of Crassostrea gigas and Their Association with Shell Pigmentation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daniels, E.V.; Reed, R.D. Xanthurenic Acid Is a Pigment in Junonia coenia Butterfly Wings. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2012, 44, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panettieri, S.; Gjinaj, E.; John, G.; Lohman, D.J. Different Ommochrome Pigment Mixtures Enable Sexually Dimorphic Batesian Mimicry in Disjunct Populations of the Common Palmfly Butterfly, Elymnias hypermnestra. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Figon, F.; Munsch, T.; Croix, C.; Viaud-Massuard, M.-C.; Lanoue, A.; Casas, J. Uncyclized Xanthommatin Is a Key Ommochrome Intermediate in Invertebrate Coloration. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 124, 103403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, M.; Kono, N.; Hirayama, A.; Malay, A.D.; Nakamura, H.; Ohtoshi, R.; Numata, K.; Tomita, M.; Arakawa, K. Xanthurenic Acid Is the Main Pigment of Trichonephila clavata Gold Dragline Silk. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thane, C.; Reddy, S. Processing of Fruit and Vegetables: Effect on Carotenoids. Nutr. Food Sci. 1997, 97, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzomo, N.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Carotenoids Functionality, Sources, and Processing by Supercritical Technology: A Review. J. Chem. 2016, 2016, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esparza-Espinoza, D.M.; Santacruz-Ortega, H.d.C.; Chan-Higuera, J.E.; Cárdenas-López, J.L.; Burgos-Hernández, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J.M. Chemical Structure and Antioxidant Activity of Cephalopod Skin Ommochrome Pigment Extracts. Food Sci. Technol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnard, M. Identification of Valuable Compounds from the Shell of the Edible Oyster Crassostrea gigas. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Figon, F.; Casas, J. Ommochromes in Invertebrates: Biochemistry and Cell Biology. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 156–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzen, B. The tryptophan → ommochrome pathway in Insects. In Advances in Insect Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1974; Volume 10, pp. 117–246. ISBN 978-0-12-024210-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, H.; Nakagoshi, M.; Mase, K.; Yamamoto, T. Occurrence of Ommochrome-Containing Pigment Granules in the Central Nervous System of the Silkworm, Bombyx mori. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000, 125, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijser, A.; Pezzella, A.; Sundström, V. Functionality of Epidermal Melanin Pigments: Current Knowledge on UV-Dissipative Mechanisms and Research Perspectives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 9119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Higuera, J.E.; Santacruz-Ortega, H.d.C.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Burgos-Hernández, A.; Robles-Sánchez, R.M.; Cruz-Ramírez, S.G.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J.M. Xanthommatin is Behind the Antioxidant Activity of the Skin of Dosidicus gigas. Molecules 2019, 24, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hori, M.; Riddiford, L.M. Isolation of Ommochromes and 3-Hydroxykynurenine from the Tobacco Hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem. 1981, 11, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, H. Ommochrome Formation and Kynurenine Excretion in Pieris brassicae: Relation to Tryptophan Supply on an Artificial Diet. J. Insect Physiol. 1979, 25, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pralea, I.-E.; Moldovan, R.-C.; Petrache, A.-M.; Ilieș, M.; Hegheș, S.-C.; Ielciu, I.; Nicoară, R.; Moldovan, M.; Ene, M.; Radu, M.; et al. From Extraction to Advanced Analytical Methods: The Challenges of Melanin Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hsiung, B.-K.; Blackledge, T.A.; Shawkey, M.D. Spiders Do Have Melanin After All. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 3632–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ostrovsky, M.A.; Zak, P.P.; Dontsov, A.E. Vertebrate Eye Melanosomes and Invertebrate Eye Ommochromes as Screening Cell Organelles. Biol. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2018, 45, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.L.; Kuchnow, K.P. Reversible, Light-Screening Pigment of Elasmobranch Eyes: Chemical Identity with Melanin. Science 1965, 150, 613–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Ischia, M.; Wakamatsu, K.; Napolitano, A.; Briganti, S.; Garcia-Borron, J.-C.; Kovacs, D.; Meredith, P.; Pezzella, A.; Picardo, M.; Sarna, T.; et al. Melanins and Melanogenesis: Methods, Standards, Protocols. Pigm. Cell Melanoma Res. 2013, 26, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, A. Coloration and chromes. In Ecophysiology of Spiders; Nentwig, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1987; pp. 16–25. ISBN 978-3-642-71554-9. [Google Scholar]

- Butenandt, A.; Biekert, E.; Koga, N.; Traub, P. Über Ommochrome, XXI. Konstitution Und Synthese Des Ommatins D. Hoppe-Seyler´s Z. Physiol. Chem. 1960, 321, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhout, H.F. Ommochrome Pigmentation of the linea and rosa Seasonal Forms of Precis coenia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1997, 36, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Fang, X.; Guo, X.; Li, L.; Luo, R.; Xu, F.; Yang, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Qi, H.; et al. The Oyster Genome Reveals Stress Adaptation and Complexity of Shell Formation. Nature 2012, 490, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Varga, M.; Berkesi, O.; Darula, Z.; May, N.V.; Palágyi, A. Structural Characterization of Allomelanin from Black Oat. Phytochemistry 2016, 130, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartlett, R.D.; Esslinger, C.S.; Thompson, C.M.; Bridges, R.J. Substituted Quinolines as Inhibitors of L-Glutamate Transport into Synaptic Vesicles. Neuropharmacology 1998, 37, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, F.; Lionetto, L.; Curto, M.; Iacovelli, L.; Cavallari, M.; Zappulla, C.; Ulivieri, M.; Napoletano, F.; Capi, M.; Corigliano, V.; et al. Xanthurenic Acid Activates mGlu2/3 Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors and Is a Potential Trait Marker for Schizophrenia. Sci. Rep. 2016, 5, 17799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartoli, F.; Misiak, B.; Callovini, T.; Cavaleri, D.; Cioni, R.M.; Crocamo, C.; Savitz, J.B.; Carrà, G. The Kynurenine Pathway in Bipolar Disorder: A Meta-Analysis on the Peripheral Blood Levels of Tryptophan and Related Metabolites. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 3419–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Solvents | Solubility |

|---|---|

| Acetic acid (1M, aqueous) | Fully soluble |

| Acetone | Not soluble |

| Cyclohexane | Not soluble |

| Chloroform | Not soluble |

| Dichloromethane | Not soluble |

| Diethyl ether | Not soluble |

| Ethanol | Slightly soluble |

| Ethyl acetate | Not soluble |

| Isopropyl alcohol | Not soluble |

| Hexane | Not soluble |

| HCl (1M, aqueous) | Fully soluble |

| Methanol | Slightly soluble |

| Methanol containing 1% of 12M HCl(aq) | Fully soluble |

| Methanol containing 0.1% of 12M HCl(aq) | Fully soluble |

| Sodium hydroxide (1M, aqueous) | Fully soluble |

| Ultrapure water | Slightly soluble |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonnard, M.; Boury, B.; Parrot, I. Xanthurenic Acid in the Shell Purple Patterns of Crassostrea gigas: First Evidence of an Ommochrome Metabolite in a Mollusk Shell. Molecules 2021, 26, 7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237263

Bonnard M, Boury B, Parrot I. Xanthurenic Acid in the Shell Purple Patterns of Crassostrea gigas: First Evidence of an Ommochrome Metabolite in a Mollusk Shell. Molecules. 2021; 26(23):7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237263

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonnard, Michel, Bruno Boury, and Isabelle Parrot. 2021. "Xanthurenic Acid in the Shell Purple Patterns of Crassostrea gigas: First Evidence of an Ommochrome Metabolite in a Mollusk Shell" Molecules 26, no. 23: 7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237263